Abstract

Background

Therapy targeting programmed death-1 or programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) has been developed for various solid malignant tumors, such as melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but this approach has little effect in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells (UCOGC) is a rare pancreatic malignancy having unique morphology and is considered a variant of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Although UCOGC has been reported to have better prognosis than conventional PDAC, the optimal treatment for UCOGC with distant metastases has not been determined.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man was initially diagnosed with NSCLC with multiple intrapulmonary metastases and abdominal lymph node metastasis in the tail of the pancreas, and bronchial biopsy and diagnostic imaging were performed. Pathologic examination of the lung showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cells expressing epithelial marker and PD-L1. Therefore, pembrolizumab monotherapy for NSCLC was given. The pulmonary lesions shrank markedly and were in complete remission after 8 months of anti-PD-1 therapy, though no therapeutic effect was observed in the pancreatic site. Distal pancreatectomy was then performed, and histopathological examination showed that the tumor was UCOGC originating from the pancreas. The histologic findings of the resected specimen mimicked those of the lung biopsy specimen, leading to the final assessment that the lung tumors were metastatic foci that migrated from the UCOGC, and only the metastatic lesions benefited from pembrolizumab therapy.

Conclusion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have limited therapeutic effects on primary lesions of pancreatic cancer, but they may exert antitumor effects on pulmonary metastases of UCOGC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a highly aggressive malignancy with a 5-year overall survival rate of 9% [1], and its incidence is increasing. Pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells (UCOGC) is an extremely rare tumor, accounting for 1.4% of invasive PCs [2], and its prognosis has been reported to be better than that of typical pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in surgically resected cases [2, 3]. But the optimal treatment for UCOGC with distant metastases is unknown. Because of the difficulties in early diagnosis, curative surgery, and chemo-resistance leading to a poor prognosis, it is imperative to establish an effective treatment approach for PC. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-programmed death-1 or programmed death-1 ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) antibody, have been developed for various solid carcinomas and have shown broad efficacy [4, 5], but they have a poor effect in the treatment of PC, as seen with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade monotherapy [6, 7]. Previous studies suggested that the tumor microenvironment (TME) plays key roles in the immunotherapy failure mechanism, with abundant stromal desmoplasia and/or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [8, 9]. In addition, DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency is an important factor for immune checkpoint inhibitor sensitive mechanism in solid tumors [10, 11]. Pembrolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against PD-1, has been reported to have strong antitumor activity in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [5, 12], although it has not shown sufficient therapeutic effects in PC. A case of UCOGC that was curatively resected following pembrolizumab monotherapy that was highly effective for metastatic lung cancer is presented.

Case presentation

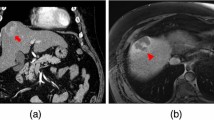

A 66-year-old man visited our hospital because of abnormal lung shadows found on screening chest X-ray examination. Positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) showed multiple nodules in bilateral lung lobes (Fig. 1a and b) and a solitary mass in the splenic hilum (Fig. 2a and b). Lung biopsy from the left middle lobe showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3a), the cells of which were immunohistochemically positive for cytokeratin (CK)- Wide Spectrum Screening (WSS) and CK-7 (Fig. 3b). Based on these findings, this patient was diagnosed as having primary NSCLC with multiple metastases to bilateral lobes and abdominal lymph node, since the mass in the tail of the pancreas was initially considered to be splenic hilum lymph node metastasis. Mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the expression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) were negative. The PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) was then performed using anti-PD-L1 antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, clones: 22c3, pharmDx assay; Dilution 1:50). Sections (4-μm thick) were prepared from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, and staining for 22c3 was performed on the Dako Link-48 autostainer system. PD-L1 expression was positive in nearly all cancer cells (Fig. 3c). Lymphocytic infiltration was abundantly observed in cancer tissue by immunohistochemical analysis using leukocyte common antigen (LCA) (Fig. 3d). Pembrolizumab monotherapy was then given. After 8 months, almost complete remission was observed in the lung tumors (Fig. 1c), whereas the size of the pancreatic mass did not decrease (Fig. 2c-e) on CT examination. This pathology raised the possibility that this pancreatic tumor might be a primary pancreatic malignancy independent of NSCLC. Contrast-enhanced CT showed a hypodense mass with peripheral irregular enhancement in the tail of the pancreas (Fig. 2c-e). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also showed a high-intensity mass on T2 and diffusion-weighted imaging, suggesting high cellularity with a cystic component (Fig. 2f-h). From these findings, this tumor was diagnosed as a primary pancreatic neoplasm unaffected by pembrolizumab, such as PDAC or a neuroendocrine tumor. After appropriate informed consent was obtained from the patient, distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy was performed about 1 year after initial diagnosis. The resected specimen showed a solid tumor, 42 mm in size, on the ventral side of the tail of the pancreas, with slight invasion into the stomach wall (Fig. 3e). Histopathological examination showed pleomorphic atypical cells, including spindle-shaped cancer cells and osteoclast-like giant cells (OGCs) (Fig. 3f and g), which infiltrated to surrounding parenchyma and the splenic vein. Regional lymph nodes showed metastatic foci. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for CK-WSS and CK-7 (Fig. 3h), and PD-L1 was also highly expressed in the tumor cells (Fig. 3i). There was small number of lymphocytes which were positive for LCA around the tumor cells, indicating scarce lymphocytic infiltration (Fig. 3j). Based on these findings, this malignancy was diagnosed as a UCOGC that arose from the pancreas. Furthermore, since these pathological characteristics were extremely similar to those of the pulmonary cancer, the diagnosis of the lung tumor as NSCLC was reconsidered. Finally, it was determined that UCOGC was the primary tumor that originated from the pancreas, and the pulmonary lesions were metastatic foci from the PC, and that pembrolizumab had little effect on the primary, but, curiously, was dramatically effective for the metastases. Microsatellite instability (MSI) is a biomarker for immunotherapy, representing the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency which predicts the favorable response of pembrolizumab to some solid malignant tumors [10, 11]. In the present case, MSI was also investigated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)- based testing which evaluates the five poly-A mononucleotide repeats (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, NR-27) [13], although repeat length alterations were not seen both in the metastatic and primary cancer specimen. This patient remains alive, and there are no signs of recurrence 6 months after the operation without anticancer therapy.

Preoperative images of the lung tumor. a Positron emission tomography (PET) before pembrolizumab therapy shows multiple tumors in bilateral lobes of the lungs (dotted circles). Marked fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake is observed in each panel (standardized uptake value (SUV) max 14.7 in the second left panel, for example). b Chest computed tomography (CT) before pembrolizumab therapy shows 4 nodules corresponding to each point of PET-CT (dotted circles). c CT imaging after pembrolizumab therapy. Almost complete remission is seen (dotted circles)

Preoperative images of the pancreatic tumor. a PET-CT before pembrolizumab therapy shows a solitary mass in the splenic hilum (arrow; SUVmax: 12.8). b Abdominal CT before pembrolizumab therapy shows a low-density mass in the splenic hilum, about 20 mm in diameter (arrow). c-e A series of contrast-enhanced CT scans after pembrolizumab therapy. The mass shows slight expansion up to 25 mm in size. This tumor is located in the tail of the pancreas, including a cystic lesion surrounded by a solid component that is irregularly enhanced in the delayed phase (arrows). f-h Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after pembrolizumab therapy. The tumor (arrows) is composed of a high-intensity moiety on the T2-weighted image (f), and surrounding parenchyma is enhanced by contrast medium in the delayed phase (g) and shows high intensity on the diffusion-weighted image (h)

Pathological examination of the lung and pancreas. a-d Transbronchial lung biopsies: The cancerous cells show pleomorphic atypical cells containing hyperchromatic nuclei in the pulmonary lesion, forming abortive glands and solid nests with fibrous stroma (a, HE, original magnification × 200). Immunohistochemical stains show cytokeratin (CK)-7-positive (b, original magnification × 200) and programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) cancer cells (c, original magnification × 200). Leukocyte common antigen (LCA) is also positive in stromal cells (d, original magnification × 200). e-j Pancreatic lesion: The hard tumor is located on the ventral side of the tail of the pancreas with anterior invasion to the stomach (dotted circle in e). Sarcomatoid appearance with spindle-shaped cells and pleomorphic multinucleated cells (f, HE, original magnification × 200). Osteoclast-like giant cells (OGCs) are also seen (arrows) in the tumor (g, HE, original magnification × 400). Immunohistochemistry: CK-7 (h) and PD-L1 (i) are also positive. Small amount of lymphocytic infiltration around the cancer cells was observed in LCA staining (j, original magnification × 200)

Discussion and conclusions

UCOGC is a rare variant of PDAC having a unique morphology which is composed of non-neoplastic cells (OGCs) and neoplastic cells (spindle and pleomorphic cells) without a definitive direction of differentiation [14, 15]. UCOGC used to be considered as an aggressive type of PC, because of the confusion of other “undifferentiated” carcinoma derived from PDAC, mucinous neoplasms and anaplastic carcinoma [16, 17]. Recent studies investigated the clinical and pathological features of pure UCOGC and concluded that patients with UCOGC had a significantly better prognosis than that with conventional PDAC or UCOGC derived from PDAC [2, 3], although the genetic alterations in UCOGC are notably similar to ordinary PDAC [3]. OGCs are the hallmark of UCOGC and defined as cells having a histologic resemblance to giant cell tumors of the bone, containing pleomorphic, multinucleated and mononucleated giant cells [18], and an abundance of OGCs is reported to correlate with favorable prognosis of UCOGC [2]. Little is known about the mechanisms of such good prognoses regardless of tumor size, though UCOGCs have been reported to have few metastases to lymph nodes or perineural invasion [2]. In the present case, distinct ductal differentiation was not seen and a large number of OGCs was observed in tumor tissue, but both distant metastases and lymph node metastases were positive. Nevertheless, this patient has had a relatively good outcome after pembrolizumab therapy followed by curative resection.

Luchini et al. reported that UCOGCs showed relatively numerous tumor cells with PD-L1 expression, and PD-L1-positive UCOGCs had a worse prognosis than PD-L1-negative ones, and the mechanism of immune evasion is a feature of UCOGCs [19]. In the present case, PD-L1 was positively expressed in many tumor cells, but the outcome was acceptable. PD-1/PD-L1 expression is a biomarker that has been associated with an increased response rate to immunotherapy [11], albeit several problems about the methodology of IHC for PD-L1 have been discussed. Different antibodies and sets of assay condition for PD-L1 have been used for respective immune checkpoint inhibitors with contrasting results [20, 21], while the most used clone for PD-L1 is SP142 [11]. Luchini et al. used clone E1L3N for PD-L1 IHC in above mentioned study [19], whereas we used 22c3 which is approved to aid in selection of patients for pembrolizumab treatment based on PD-L1 expression in FFPE tumor samples [22]. It is reported that 22c3 was prone to show lower mean score of PD-L1 expression in IHC for NSCLC compared to E1L3N [21], therefore it is unlikely that our results of PD-L1 high expression in IHC was false positive. In fact, it is reasonable to assume that PD-1 antibody has normalized the cancer immune evasion system and has dramatically improved the prognosis of this patient.

Although there are no reports of anti-PD-1 therapy having sufficient effects in UCOGC with distant metastasis, a case in which pembrolizumab was very effective against the lung metastases of UCOGC was presented. PD-L1 expression in lung lesions was almost 100% in the present case, but it is known that the effect of anti-PD-1 antibody is not linked solely to the expression levels of PD-L1 in tumor tissues. It is well known that the TME, including TILs and tumor-associated macrophage (TAMs), is involved in the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors [23]. The abundance of stromal desmoplasia also constitutes a principal characteristic of the PC TME [24]. In fact, PD-L1 was highly expressed in the tumor cells of PC, but pembrolizumab did not have a significant effect in the present case. However, the pancreatic tumor showed stable disease for several months, so it may have had some effect on the PC. Smyth et al. suggested that the TME should be categorized into four types based on the number of TILs and the PD-L1 expression level [8]. In the present case, PD-L1 expression was highly and equivalently confirmed in both lesions (Fig. 3c and i), whereas lymphocytic infiltration was stronger in the lung metastatic lesions than in the primary pancreatic lesion (Fig. 3d and j). Such variance in the TME might reflect the different effects of pembrolizumab at the two sites.

It has been reported that colorectal cancers with MMR deficiency are sensitive to immune checkpoint inhibitor [25]. Le et al. evaluated the sensitivity of MMR-deficient cancers to immune checkpoint inhibitor across 12 different tumor types including PCs, and the efficacy of pembrolizumab against MMR-deficient cancers was evaluated regardless of the cancer types [10]. In this study, complete responses were achieved in 21% of patients, verifying the hypothesis that large population of mutant neoantigens in MMR-deficient cancers make them sensitive to immune checkpoint blockage. However, MMR deficiency was observed less than 2% of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in advanced stage in this study [10], correspondingly in the present case with MSI negative. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends MMR IHC as a first method for MSI testing for immunotherapy [11], though MSI-PCR with five poly-A mononucleotides is also recommended as the current standard because of its high specificity and sensitivity [11, 13]. It is difficult to explain the present result that Pembrolizumab exerted sufficient efficacy against metastatic pulmonary lesions which was negative for MSI-PCR, exclusively by the MMR-deficient theory. Moreover, ESMO recommends novel next-generation sequencing (NGS) which permits a high-throughput sequencing of large number of microsatellites and genes with the determination of tumor mutational burden (TMB). TMB is also an emerging biomarker of sensitivity to immunotherapy and the abundance of TMB is known to correlate with the predictive upregulation of neoantigens [26], although we could not evaluate the TMB of UCOGC in this case. It was suggested that only 16% of cancers with high TMB were classified as MSI-high and the co-occurrence of these two phenotypes was highly dependent on the cancer type [27]. Le et al. also investigated the TMB in both primary and metastatic cancers in some cases, and showed the distinct difference of mutational genes and TMB between metastatic and primary cancers [10], indicating variable efficacy of immunotherapy depending on each organ. NGS-based MSI testing has the potential to become the method of choice for all tumor types, including rare cancers such as UCOGC.

Although MSI, TMB, tumor neoantigen and PD-1/PD-L1 expression are biomarkers that associated with response rate to immune checkpoint inhibitors, preferable response rates to immunotherapy has been described also in tumors without the expression of such biomarkers [28, 29]. Luchini et al. demonstrated the relationships among MSI, high TMB and PD-L1 expressions, and only 2.9% was positive for all these three parameters among the 4186 cancer patients [11]. Further studies are needed to find new biomarkers which can precisely predict the response to immunotherapy.

There are few reports of effective immune checkpoint inhibitors for PC, and many of them are investigations focusing on the effects on primary lesions. The validation of the effectiveness of anti-PD-1 antibody on distant metastases is a future issue to be considered. Because of genetical similarities, the establishment of the new treatment approach for UCOGC in advanced stage may be helpful to improve the prognosis of the patients with PDAC.

In conclusion, immune checkpoint inhibitors have limited therapeutic effects on primary lesions of PC, but they may exert antitumor effects on distant metastases of UCOGC.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-1 ligand-1

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small-cell lung cancer

- UCOGC:

-

Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells

- PDAC:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PC:

-

Pancreatic cancer

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- TIL:

-

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

- MMR:

-

Mismatch repair

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- WSS:

-

Wide spectrum screening

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ALK:

-

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- FFPE:

-

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded

- LCA:

-

Leukocyte common antigen

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OGC:

-

Osteoclast-like giant cell

- MSI:

-

Microsatellite instability

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- TAM:

-

Tumor-associated macrophage

- ESMO:

-

European society for medical oncology

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- TMB:

-

Tumor mutational burden

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- SUV:

-

Standardized uptake value

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34.

Muraki T, Reid MD, Basturk O, Jang KT, Bedolla G, Bagci P, Mittal P, Memis B, Katabi N, Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Undifferentiated carcinoma with Osteoclastic Giant cells of the pancreas: Clinicopathologic analysis of 38 cases highlights a more protracted clinical course than currently appreciated. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(9):1203–16.

Luchini C, Pea A, Lionheart G, Mafficini A, Nottegar A, Veronese N, Chianchiano P, Brosens LA, Noë M, Offerhaus GJA, et al. Pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells is genetically similar to, but clinically distinct from, conventional ductal adenocarcinoma. J Pathol. 2017;243(2):148–54.

Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(26):2443–54.

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, Gottfried M, Peled N, Tafreshi A, Cuffe S, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33.

Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, Sosman JA, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Gettinger SN, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515(7528):563–7.

Patnaik A, Kang SP, Rasco D, Papadopoulos KP, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Beeram M, Drengler R, Chen C, Smith L, Espino G, et al. Phase I study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475; anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4286–93.

Smyth MJ, Ngiow SF, Ribas A, Teng MW. Combination cancer immunotherapies tailored to the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(3):143–58.

Blando J, Sharma A, Higa MG, Zhao H, Vence L, Yadav SS, Kim J, Sepulveda AM, Sharp M, Maitra A, et al. Comparison of immune infiltrates in melanoma and pancreatic cancer highlights VISTA as a potential target in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(5):1692–7.

Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–13.

Luchini C, Bibeau F, Ligtenberg MJL, Singh N, Nottegar A, Bosse T, Miller R, Riaz N, Douillard JY, Andre F, et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1232–43.

Velcheti V, Chandwani S, Chen X, Pietanza MC, Burke T. First-line pembrolizumab monotherapy for metastatic PD-L1-positive NSCLC: real-world analysis of time on treatment. Immunotherapy. 2019;11(10):889–901.

Goel A, Nagasaka T, Hamelin R, Boland CR. An optimized pentaplex PCR for detecting DNA mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9393.

Koorstra JB, Maitra A, Morsink FH, Drillenburg P, ten Kate FJ, Hruban RH, Offerhaus JA. Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells (UCOCGC) of the pancreas associated with the familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMM). Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(12):1905–9.

Luchini C, Capelli P, Scarpa A. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its variants. Surg Pathol Clin. 2016;9(4):547–60.

Lukas Z, Dvorak K, Kroupova I, Valaskova I, Habanec B. Immunohistochemical and genetic analysis of osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;32(3):325–9.

Nai GA, Amico E, Gimenez VR, Guilmar M. Osteoclast-like giant cell tumor of the pancreas associated with mucus-secreting adenocarcinoma. Case report and discussion of the histogenesis. Pancreatology. 2005;5(2–3):279–84.

Moore JC, Bentz JS, Hilden K, Adler DG. Osteoclastic and pleomorphic giant cell tumors of the pancreas: a review of clinical, endoscopic, and pathologic features. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2(1):15–9.

Luchini C, Cros J, Pea A, Pilati C, Veronese N, Rusev B, Capelli P, Mafficini A, Nottegar A, Brosens LAA, et al. PD-1, PD-L1, and CD163 in pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells: expression patterns and clinical implications. Hum Pathol. 2018;81:157–65.

Munari E, Zamboni G, Lunardi G, Marconi M, Brunelli M, Martignoni G, Netto GJ, Quatrini L, Vacca P, Moretta L, et al. PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer: evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of a laboratory-developed test using clone E1L3N in comparison with 22C3 and SP263 assays. Hum Pathol. 2019;90:54–9.

Rimm DL, Han G, Taube JM, Yi ES, Bridge JA, Flieder DB, Homer R, West WW, Wu H, Roden AC, et al. A prospective, multi-institutional, pathologist-based assessment of 4 immunohistochemistry assays for PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(8):1051–8.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Perez-Gracia JL, Felip E, Kim DW, Han JY, Molina JR, Kim JH, Dubos Arvis C, Ahn MJ, et al. Use of archival versus newly collected tumor samples for assessing PD-L1 expression and overall survival: an updated analysis of KEYNOTE-010 trial. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(2):281–9.

Feng M, Xiong G, Cao Z, Yang G, Zheng S, Song X, You L, Zheng L, Zhang T, Zhao Y. PD-1/PD-L1 and immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;407:57–65.

Zischek C, Niess H, Ischenko I, Conrad C, Huss R, Jauch KW, Nelson PJ, Bruns C. Targeting tumor stroma using engineered mesenchymal stem cells reduces the growth of pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250(5):747–53.

Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn RB, Shia J, Segal NH, Diaz LA Jr. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(6):361–75.

Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):48–61.

Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, Schrock A, Campbell B, Shlien A, Chmielecki J, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):34.

Hissong E, Ramrattan G, Zhang P, Zhou XK, Young G, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Fernandes H, Yantiss RK. Gastric carcinomas with lymphoid Stroma: an evaluation of the Histopathologic and molecular features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(4):453–62.

Salem ME, Puccini A, Grothey A, Raghavan D, Goldberg RM, Xiu J, Korn WM, Weinberg BA, Hwang JJ, Shields AF, et al. Landscape of tumor mutation load, mismatch repair deficiency, and PD-L1 expression in a large patient cohort of gastrointestinal cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(5):805–12.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received in support of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MO and YS conceived of and designed the article. HS performed pembrolizumab therapy for lung cancer. YT made the clinical diagnosis of pancreatic lesion. MN made the pathological diagnosis. TK, YH, TS, KH, MY, and HM supervised the writing of the manuscript. The other co-authors collected data and discussed the content of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written, informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Obayashi, M., Shibasaki, Y., Koakutsu, T. et al. Pancreatic undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells curatively resected after pembrolizumab therapy for lung metastases: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 20, 220 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01362-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01362-4