Abstract

Background

Colonoscopy as a screening and diagnostic tool is generally safe and well-tolerated, and significant complications are rare. The rate of more mild adverse effects is difficult to estimate, particularly when such effects do not result in hospital admission. We aimed to identify the rate and timing of adverse effects as reported by users querying symptoms on an internet search engine.

Methods

We identified queries made to Bing originating from users in the United States containing the word “colonoscopy” during a 12-month period and identified those queries in which the timing of colonoscopy could be estimated. We then identified queries from those same users for medical symptoms during the time span from 5 days before through 30 days after the colonoscopy date.

Results

Of 641,223 users mentioning colonoscopy, 7013 (1.1%) had a query that enabled identification of their colonoscopy date. The majority of queries about colonoscopy preceded the procedure, and concerned diet. 28% of colonoscopy-related queries were made afterwards, and included queries about diarrhea and cramps, with 2.6% of users querying respiratory symptoms after the procedure, including cough (1.2%) and pneumonia (0.6%). Respiratory symptoms rose significantly at days 7–10 after the colonoscopy.

Conclusions

Internet search queries for respiratory symptoms rose approximately one week after queries relating to colonoscopy, raising the possibility that such symptoms are an under-reported late adverse effect of the procedure. Given the widespread use of colonoscopy as a screening modality and the rise of anesthesia-assisted colonoscopy in the United States in recent years, this signal is of potential public health concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colonoscopy is the most commonly used method for colorectal cancer screening in the United States, and nearly 60% of individuals eligible for colorectal cancer screening have undergone this procedure [1]. Among individuals undergoing alternative modes of screening, such as fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy is mandated for those who have a positive screening test, and colonoscopy is the effector arm of all colorectal cancer screening tests [2].

Given its widespread use in the general population, the effectiveness of colonoscopy is dependent on its safety profile, particularly when it is employed as a primary screening modality in asymptomatic individuals. Numerous studies have confirmed that the rate of serious complications after colonoscopy is low, and that the most severe complications of the procedure (perforation, bleeding, and mortality) have declined in recent years [3]. However, respiratory complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, may be an underappreciated sequela of colonoscopy, particularly when deep sedation with anesthesia assistance is provided [4, 5, 6]. As rates of anesthesia assistance during colonoscopy have increased markedly in recent years [7, 8], there is concern that respiratory complications may be an increasingly common event.

Prior studies of colonoscopy complications focused on the severe end of the spectrum, and mostly relied on post-colonoscopy emergency department visits or hospitalizations to identify complications [3, 4, 9,10,11,12,13,14]. Such methods likely underestimate more mild, but still clinically significant events that do not meet the threshold for acute care, such as a febrile respiratory illness with cough. These events are difficult to measure using traditional measures, but may be estimated using search engine queries [15]. Such a strategy has been used to estimate the prevalence of symptoms that did rise to the threshold of seeking care, but that preceded a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas [16].

In this study we aimed to determine the prevalence and timing of post-colonoscopy complications using search engine queries.

Methods

Data

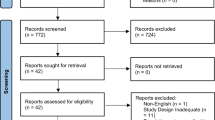

We extracted all queries made to Bing from people in the USA between October 1st, 2017 and September 30th, 2018 (one year). Each query comprised of an anonymized user identifier, the time and date of the query, and its text. The queries were filtered to include those queries which contained the word “colonoscopy” and any query made by people who searched for this word. The age and gender of users, as provided by users when they registered with Bing, was available for a subset (23%) of the users.

Timing of colonoscopy

Queries that mentioned colonoscopy were filtered to include those that mentioned a reference date. These queries included text in the form of “colonoscopy in X days,” “colonoscopy X days ago,” “colonoscopy tomorrow,” or “colonoscopy yesterday.” These queries allowed us to pinpoint the date on which colonoscopies occurred for each user. The time of each query was normalized to the calculated date of colonoscopy.

Adverse events

Other queries made by people for whom colonoscopies could be timed were filtered to include those queries which mentioned one or more of 195 medical symptoms and their synonyms [17]. This list was augmented with terms related to fainting, pneumonia, and bronchitis, as well as with a list of common antibiotics.

We calculated the number of people who queried for each of the symptoms as a function of time, relative to the colonoscopy date, between 5 days before the date of colonoscopy and until 30 days after it. This number was first normalized to the probability of querying for the symptom over the entire time range. In line with previous work [18], we then normalized this probability by the probability of a user who underwent colonoscopy to ask about any symptom on each day. Finally, we filtered the time series using a 3-day moving average. We refer to this time series as the symptom ratio time series (SRTS). SRTS were retained for those symptoms which were queried for by 75 people or more. To calculate significant SRTS values we found the 5% highest values of SRTS among all SRTSs.

Results

During the 12-month period, 641,223 people mentioned colonoscopy in their queries. Among them, a total of 7013 users made queries that enabled identification of their colonoscopy date. Females accounted for 60.0% of users in our data. Figure 1 shows the age distribution of the 947 people who underwent colonoscopy for whom age data were available. The median age was 58 years, and the most common age group was 60–64 years.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of queries by 7013 who mentioned time relative to the colonoscopy date, where positive numbers indicated that the query was made after the colonoscopy (e.g., “I had colonoscopy yesterday”). The figure shows that many more people ask about issues related to colonoscopy before the procedure than after it.

Table 1 shows the most common words and word pairs before and after the procedure, excluding stopwords [19], words about the number of days relative to colonoscopy, or the word “colonoscopy.” The table also shows the most common queries before and after the procedure. As the table demonstrates, concerns prior to colonoscopy include mostly the diet required before it, while queries after the procedure refer mostly to adverse events associated with colonoscopy.

Adverse reactions

Of all symptom queries made in the peri-procedure period, 28% were made after the procedure. Figure 3 shows the 15 symptoms, conditions and drugs that had more than three days with statistically significant SRTS values. Table 2 shows the percentage of users (n = 7013) who asked about each of the terms in Fig. 3 after the colonoscopy. As the figure shows, for some symptoms tend to cluster during the first few days after colonoscopy (bloating, nausea, stomach pain and tiredness). However, other symptoms exhibit statistically significant high values of SRTS in later days. These include respiratory symptoms such as cough and queries for pneumonia, as well as fever, headaches, and weight gain.

Table 2 also shows the average age and percent of females who asked about each symptom. Interestingly, females ask more about respiratory symptoms (with the exception of hemoptysis), while the general symptoms are slightly more common among males, with the exception of bloating and nausea.

Discussion

In this analysis of colonoscopy-related internet search queries, we found that queries were far more common before the procedure than after the procedure, and that pre-procedure diet was the most commonly queried subject. But we also found that a substantial minority of patients (28%) query symptoms in the days following colonoscopy, and that there was a measurable increase in queries related to respiratory symptoms, suggesting that aspiration during the procedure may be an under-reported adverse effect of colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy has been associated with a reduced mortality from colorectal cancer in case-control and cohort studies [20,21,22], and the risk of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer has been linked to a measure of colonoscopy quality, the adenoma detection rate [23]. The decrease in colorectal cancer incidence in the United States in recent decades can be attributed in part to the uptake in screening for colorectal cancer, in which precancerous adenomas are identified and removed during colonoscopy [24, 25]. At the same time, there is evidence that colonoscopy may be overused in some contexts, in which patients undergo the procedure more frequently than recommended by guidelines [26, 27], undermining cost-effectiveness and exposing patients to risks without a clear incremental benefit.

As colonoscopy is a frequently-performed procedure on a large proportion of the population, it is particularly relevant to identify relatively mild symptoms that may not reach the threshold of detection using claims-based analyses that rely on health care encounters. Such studies have found that respiratory complications are rare. For instance, a population-based cohort study of the 5% sample of cancer-free Medicare beneficiaries in SEER-Medicare regions found that hospitalization for aspiration was the most frequent complication of colonoscopy, but occurred in less than 0.2% cases [6]. Similarly, an analysis of Health Care Cost and Utilization Project data from California on screening and surveillance colonoscopy performed between 2005 and 2011 (n = 1.58 million) found that the rate of emergency department visits or hospital admissions for pulmonary complications within 30 days following the procedure was 31 per 10,000 (0.3%) [10]. Our study, that found a pulmonary symptom rate of 2.6%, suggests that the previously documented rare risk of aspiration represents the most severe end of the spectrum of such symptoms, and that more mild symptoms are under-reported yet present.

The finding of a respiratory signal peaking one week after colonoscopy is of particular concern given the secular trend of increasing use of anesthesia assistance during this procedure [7, 8, 28]. Although the use of anesthesia assistance is associated with increased patient satisfaction and improved throughput, two large studies in the United States found a small but statistically significant increase in the risk of aspiration pneumonia following colonoscopy with anesthesia assistance as compared to those utilizing conscious sedation [4, 5].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify self-reported symptoms after colonoscopy using internet queries. Such a strategy has been used to identify symptoms compatible with respiratory syncytial virus, and has tracked with CDC-monitored rates [29]. Though the methodology and findings are novel, we acknowledge that this study has a number of limitations. We were unable to confirm the veracity of these estimates for colonoscopy dates via medical record review; a user querying diet before colonoscopy symptoms after a colonoscopy may be querying on behalf of a friend or relative, or may be asking such questions hypothetically. Selection bias is also a concern. Only a small proportion (1.1%) of users who queried colonoscopy had an estimatable date of the procedure based on the query, and of such users, only 28% queried any symptoms afterward. Users who queried any symptoms may be different in important ways from users who did not query symptoms after colonoscopy.

Conclusion

We found that internet search queries for respiratory symptoms rose approximately one week after queries relating to colonoscopy, raising the possibility that such symptoms are an under-reported late adverse effect of the procedure. Given the widespread use of colonoscopy as a screening modality and the rise of anesthesia-assisted colonoscopy in the United States in recent years, this signal is of potential public health concern. Future studies should focus on measuring the incidence of and risk factors for cough and other respiratory symptoms following colonoscopy, recording the type of sedation used, employing a prospectively administered questionnaire, and including a non-colonoscopy control group. Such as study, designed to identify symptoms that do not necessarily reach the threshold for hospitalization, would clarify the potential safety signal identified in this analysis.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Microsoft, but restrictions apply to the availability of the data. Individual-level search data are available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission of Microsoft.

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control

- SEER:

-

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results program

- STRS:

-

Symptom ratio time series

References

de Moor JS, Cohen RA, Shapiro JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in the United States: trends from 2008 to 2015 and variation by health insurance coverage. Prev Med. 2018;112:199–206.

Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal Cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307–23.

Reumkens A, Rondagh EJA, Bakker CM, Winkens B, Masclee AAM, Sanduleanu S. Post-colonoscopy complications: a systematic review, time trends, and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1092–101.

Bielawska B, Hookey LC, Sutradhar R, et al. Anesthesia assistance in outpatient colonoscopy and risk of aspiration pneumonia, bowel perforation, and splenic injury. Gastroenterol. 2018;154(1):77–85.e3.

Wernli KJ, Brenner AT, Rutter CM, Inadomi JM. Risks associated with anesthesia services during colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(4):888–94 quiz e18.

Cooper GS, Kou TD, Rex DK. Complications following colonoscopy with anesthesia assistance: a population-based analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):551–6.

Krigel A, Chen L, Wright JD, Lebwohl B. Substantial increase in anesthesia assistance for outpatient colonoscopy and associated cost nationwide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; in press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1542356519300102.

Khiani VS, Soulos P, Gancayco J, Gross CP. Anesthesiologist involvement in screening colonoscopy: temporal trends and cost implications in the medicare population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(1):58–64.e1.

Ko CW, Riffle S, Michaels L, et al. Serious complications within 30 days of screening and surveillance colonoscopy are uncommon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(2):166–73.

Wang L, Mannalithara A, Singh G, Ladabaum U. Low Rates of Gastrointestinal and Non-Gastrointestinal Complications for Screening or Surveillance Colonoscopies in a Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):540–555.e8.

Levin TR, Zhao W, Conell C, et al. Complications of colonoscopy in an integrated health care delivery system. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):880–6.

Rutter CM, Johnson E, Miglioretti DL, Mandelson MT, Inadomi J, Buist DSM. Adverse events after screening and follow-up colonoscopy. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(2):289–96.

Singh H, Penfold RB, DeCoster C, et al. Colonoscopy and its complications across a Canadian regional health authority. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):665–71.

Leffler DA, Kheraj R, Garud S, et al. The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(19):1752–7.

Yom-Tov E. CCrowdsourced health: How what you do on the Internet will improve medicine. Cambridge: Mit Press; 2016.

Paparrizos J, White RW, Horvitz E. Screening for pancreatic adenocarcinoma using signals from web search logs: feasibility study and results. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(8):737–44.

Yom-Tov E, Gabrilovich E. Postmarket drug surveillance without trial costs: discovery of adverse drug reactions through large-scale analysis of web search queries. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(6):e124.

Richardson M. Learning about the world through long-term query logs. ACM Trans Web. 2008;2(4):1–27.

Munková D, Munk M, Vozár M. Influence of stop-words removal on sequence patterns identification within comparable corpora. In: Trajkovik V, Anastas M, editors. ICT innovations 2013. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 67–76.

Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1095–105.

Baxter NN, Warren JL, Barrett MJ, Stukel TA, Doria-Rose VP. Association between colonoscopy and colorectal cancer mortality in a US cohort according to site of cancer and colonoscopist specialty. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2664–9.

Kahi CJ, Pohl H, Myers LJ, Mobarek D, Robertson DJ, Imperiale TF. Colonoscopy and colorectal Cancer mortality in the veterans affairs health care system: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(7):481–8.

Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1298–306.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34.

Welch HG, Robertson DJ. Colorectal Cancer on the decline--why screening Can’t explain it all. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1605–7.

Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo Y-F. Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1335–43.

Sheffield KM, Han Y, Kuo Y-F, Riall TS, Goodwin JS. Potentially inappropriate screening colonoscopy in Medicare patients: variation by physician and geographic region. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):542–50.

Inadomi JM, Gunnarsson CL, Rizzo JA, Fang H. Projected increased growth rate of anesthesia professional-delivered sedation for colonoscopy and EGD in the United States: 2009 to 2015. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(3):580–6.

Oren E, Frere J, Yom-Tov E, Yom-Tov E. Respiratory syncytial virus tracking using internet search engine data. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):445.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None Received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: BL, EYT. Acquisition of data: EYT.

Analysis and interpretation of data: BL, EYT. Drafting of the manuscript: BL, EYT.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: BL, EYT. Statistical analysis: EYT. Study supervision: BL, EYT. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript in its current state.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Behavioral Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology, approval number 2018–032 on May 27th, 2018. All data were stored on secure media at Microsoft. Written informed consent by study participants was deemed exempt by the Ethics Committee. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

EYT is an employee of Microsoft, owner of the Bing search engine. BL declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yom-Tov, E., Lebwohl, B. Adverse events associated with colonoscopy; an examination of online concerns. BMC Gastroenterol 19, 207 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1127-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-019-1127-5