Abstract

Background

The role of HLA-DR antigens in the clinicopathological features of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is not clearly understood. We examined the implications of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese AIH, including the effect of HLA-DR4 on the age and pattern of AIH onset, clinicopathological features, and treatment efficacy.

Methods

A total of 132 AIH patients consecutively diagnosed and treated in 2000–2014 at 2 major hepatology centers of eastern Tokyo district were the subjects of this study. The frequency of HLA-DR phenotypes was compared with that in the healthy Japanese population. AIH patients were divided into HLA-DR4–positive or HLA-DR4–negative groups and further sub-classified into elderly and young-to-middle-aged groups, and differences in clinical and histological features were examined. Clinical features associated with the response to immunosuppressive therapy were also determined.

Results

The frequency of the HLA-DR4 phenotype was significantly higher in AIH than in control subjects (59.7 % vs. 41.8 %, P < 0.001), and the relative risk was 2.14 (95 % CI; 1.51–3.04). HLA-DR4–positive AIH patients were younger than HLA-DR4–negative patients (P = 0.034). Serum IgG and IgM levels were higher (P < 0.001 and P = 0.007, respectively) in HLA-DR4–positive patients. These differences were more prominent in elderly AIH patients. However, there was no difference in IgG and IgM levels between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative patients of the young-to-middle-aged group. There were no differences in the histological features. In patients with refractory to immunosuppressive therapy, higher total bilirubin, longer prothrombin time, lower serum albumin, and lower platelet count were found. Imaging revealed splenomegaly to be more frequent in refractory patients than in non-refractory patients (60.0 % vs. 30.8 %, P = 0.038). HLA-DR phenotype distribution was similar regardless of response to immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusions

HLA-DR4 was the only DR antigen significantly associated with Japanese AIH. The clinical features of HLA-DR4–positive AIH differed between elderly patients and young-to-middle-aged patients. Treatment response depended on the severity of liver dysfunction but not on HLA-DR antigens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a rare inflammatory liver disease, with prevalence rates of 5–20 per 100,000 in Europe and North America [1, 2]. Although the etiology of AIH remains unknown, AIH predominantly affects women and is characterized by a marked elevation of serum immunoglobulin levels and the emergence of autoantibodies [3, 4]. The diagnosis relies on a combination of indicative features of AIH and exclusion of other liver diseases. To confirm the diagnosis of AIH, a set of diagnostic criteria, the International Diagnostic Criteria for the Diagnosis of AIH, is generally applied [5]. AIH is classified as type 1 or type 2 according to the type of autoantibodies [6–8]. In Japan, most cases of AIH have been found to be of type 1 [9].

As regards the immunogenetic background of AIH, HLA-DR3 (recently split into DR17 and DR18) and HLA-DR4 are associated with type 1 AIH [10]. In Japan, HLA-DR4 is frequently found in AIH patients, as has been shown in European or North American Caucasoid patients. However, HLA-DR3–positive AIH is quite rare, because the prevalence of DR3 is extremely rare in the normal Japanese population [9].

In a report on North American patients, the clinical features of HLA-DR4–positive AIH differed from those of HLA-DR4–negative patients [11]. In addition, the clinical features of AIH in elderly patients differed from those of younger patients [12–14]. Recently, a lower frequency of HLA-DR4 and a higher frequency of histologically acute hepatitis were reported in adolescent and early adulthood AIH [14]. Moreover, elderly AIH has been increasing in Japan. However, the role of the HLA-DR antigen on the clinical features, including age at onset of AIH and treatment efficacy, has not been extensively studied.

In the present study, we thoroughly examined the role of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese AIH, including how HLA-DR4 influences the age of AIH onset and its clinical features. The association of HLA-DR antigens with the treatment efficacy was also examined.

Methods

Study population and study design

A total of 132 patients who had been consecutively diagnosed with AIH, treated, and examined for the HLA-DR antigen at Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital and the Jikei University School of Medicine Katsushika Medical Center (2 of the major hepatology centers in eastern Tokyo district) from the beginning of 2000 till May 2014 were the subjects of this study. AIH diagnosis was based on the Diagnostic Criteria of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAHG) [2], which defines AIH on the basis of definite or empirical judgment by experienced hepatologists after ruling out other liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis, drug-induced liver disease, hemochromatosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson’s disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, active cytomegalovirus infection, active Epstein–Barr virus infection, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, congestive liver injury, and ischemia.

The medical records of the subjects at the time of diagnosis were collected and analyzed retrospectively. In addition, the clinical course of all AIH patients was surveyed. The collected laboratory data included aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin (TB), albumin (Alb), platelet count (PLT), prothrombin time (PT), immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA), HCV- and HBV-related viral markers, drug history, average alcohol intake, liver histology, other concomitant autoimmune diseases, and other defined autoantibodies. ANA and AMA were detected and titrated by standard indirect immunofluorescence. For imaging, computed tomography and/or ultrasonography were performed for all but 4 patients, and the presence or absence of splenomegaly was evaluated by radiologists. HLA-DR antigens were assayed in all patients by PCR-based reverse sequence specific oligonucleotide typing (SRL or BML, Tokyo, Japan). Pre-treatment AIH score was calculated in every patient. Then, the frequencies of HLA-DR phenotypes were assessed, and the importance of HLA-DR4 in clinical features in elderly or younger AIH patients was analyzed. The effect of HLA-DR antigens on response to immunosuppressive therapy was also examined.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethical committee of Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital and the Ethical committee of the Jikei University School of Medicine. Information of the protocol of this study was explained to the participants, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study complied with the standards of the 2008 Declaration of Helsinki and current ethical guidelines.

Sub-grouping of AIH patients according to HLA-DR4

AIH patients were divided into HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative groups. They were further sub-classified into an elderly group (diagnosed at ≥65 years; 49 patients) and a young-to-middle-aged group (diagnosed at ≤55 years; 49 patients). In each age group, the differences in the clinical features between HLA-DR4 − positive and HLA-DR4 − negative patients were examined.

Histological examination

Sufficient liver tissue (longer than 2 cm, obtained by 16- or 18-gauge needles) was obtained by percutaneous liver biopsy before starting therapy in 116 out of 132 AIH patients. Among the remaining 16 patients, consent for liver biopsy could not be obtained in 2; immunosuppressive drugs had already been taken based on the clinical diagnosis of AIH in 3; and percutaneous liver biopsy was contraindicated because of severe liver damage in 8 patients. Biopsy specimens could not be obtained in 2 patients, and sufficient length of biopsy specimen was not achieved in 1 patient. The biopsy samples were stained by hematoxylin/eosin and Masson’s trichrome or Azan. The pathological features of AIH were determined collectively by a single pathologist (AS) blinded to clinical information. Pathological scoring of AIH based on the degree of interface hepatitis, predominance of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and presence of rosetting of liver cells was performed according to the diagnostic criteria of the IAHG [2]. In addition, histological staging was assessed based on the Metavir score (F0: no fibrosis, F1: portal fibrosis without septa, F2: portal fibrosis with few septa, F3: numerous septa without cirrhosis and F4: cirrhosis). F0-F2 was considered non-to-mild fibrosis, while F3-F4 was considered advanced fibrosis.

Criteria of acute or chronic AIH

Patients with acute liver dysfunction (serum ALT levels higher than 10 times of the upper normal limit) or with acute liver-related symptoms (fatigue, jaundice, and appetite loss) without evidence of liver dysfunction in the past (more than 6 months before diagnosis) was defined as acute-onset AIH, while the others were defined as chronic onset AIH. This classification was based on a report by Miyake et al. [15].

Distribution of HLA-DR antigens in AIH

HLA-DR phenotype frequencies in AIH were determined and compared with those in a large-scale population study on healthy Japanese people by the HLA Laboratory, Kyoto, Japan [16].

Treatment of AIH patients

Of 132 AIH patients, 121 (92 %) were treated by prednisolone alone or in combination with an immunomodulator (azathioprine, cyclosporine, or tacrolimus). The remaining 11 patients were treated with ursodeoxycholic acid alone because of mild inflammatory activity [17]. Prednisolone alone and in combination with azathioprine was defined as the “standard therapy.” The initial doses of prednisolone were 0.2–1.0 mg/kg except for 2 patients for whom methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1000 mg/day) was selected. Prednisolone doses were gradually decreased to maintenance doses of 10 mg/day or less. Azathioprine doses were adjusted to 0.5–1 mg/kg and maintained [2]. The other immunomodulators were used for patients who were resistant to the standard therapy or could not continue azathioprine use because of adverse reaction [2, 18, 19].

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as number (%) or median (minimum–maximum). Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test was used to analyze differences in categorical data. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze differences between continuous variables. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed test and P-values of ≤0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATISTICA for Windows version 6 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Frequency of HLA-DR phenotypes in AIH patients

The frequency of the HLA-DR4 phenotype was significantly higher in AIH than in control individuals (59.7 % vs. 41.8 %, P < 0.001). The relative risk (RR) of HLA-DR4 was 2.14 (95 % CI; 1.51–3.04).

Among the other HLA-DR antigens, HLA-DR14 tended to be more frequent and HLA-DR11, HLA-DR12, and HLA-DR15 less frequent in AIH compared with control subjects, although the differences were not statistically significant (Table 1).

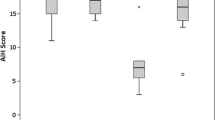

Comparison of clinical features between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative AIH

HLA-DR4–positive AIH patients were younger than HLA-DR4–negative patients. Serum IgG and IgM levels were higher in HLA-DR4–positive patients than in HLA-DR4–negative patients. Splenomegaly was less frequently seen in HLA-DR4–positive AIH, but the difference was not statistically significant. Otherwise, differences were not observed in the remaining demographic or laboratory data, including AST, ALT, ALP, ANA titers, fibrosis stage or pretreatment AIH scores (Table 2).

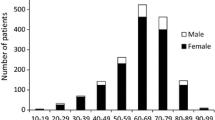

Differences in the effect of HLA-DR4 between young-to-middle-aged and elderly AIH patients

According to the age distribution of HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative AIH patients, AIH developed most frequently in individuals in their 50s in HLA-DR4–positive patients and in their 70s in HLA-DR4–negative patients. HLA-DR4–positive AIH was more frequent than HLA-DR4–negative AIH in the age group of 20–59 years. HLA-DR4–negative AIH, however, was more frequent than HLA-DR4–positive AIH in individuals in their 70s (Fig. 1)

In AIH patients diagnosed at age 65 and above (elderly AIH), 22 patients had HLA-DR4, while 27 did not. Both serum IgG and IgM levels were higher in elderly HLA-DR4–positive AIH patients than in HLA-DR4–negative patients. These differences between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative elderly AIH patients were greater than those shown with the whole population. Moreover, pretreatment AIH scores (including histological score) were significantly higher in the HLA-DR4–positive group than in the HLA-DR4–negative group. Advanced fibrosis tended to be more frequent in HLA-DR4–positive elderly AIH patients (Table 3). With regard to the HLA-DR distribution in elderly AIH patients, the HLA-DR4 phenotype comprised only 44.9 %, and none of HLA-DR antigens were associated with elderly AIH.

In AIH patients younger than 55 years (young-to-middle-aged AIH), 34 of 49 (63.8 %) patients had HLA-DR4. The clinicopathological features between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative AIH were similar except for splenomegaly, which was less frequently found in HLA-DR4–positive patients. In contrast to elderly AIH, serum levels of IgG and IgM or pretreatment AIH scores (including histological score) did not differ between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative patients. Moreover, the fibrosis stage was similar between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative AIH (Table 4).

Treatment outcome and HLA-DR antigens

Normalization of serum ALT/AST level was accomplished within 6 months in 106 out of 121 patients by the standard therapy. In the remaining 15 patients, 8 developed liver failure and/or died due to liver-related complications, and 7 went into remission by additional dosage of cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

The acute-onset AIH was more frequent in the patients in whom remission was induced by the standard therapy within 6 months (non-refractory group) than in the patients resistant to the standard therapy (refractory group). Splenomegaly was less frequently found in the non-refractory group than in the refractory group. TB was lower, PT was longer, and Alb and PLT were higher in the non-refractory group. Moreover, the serum ALP level was lower in the non-refractory group. The occurrence of advanced liver fibrosis was not different, but the number of patients who did not undergo liver biopsy was higher in the refractory group than in the non-refractory group (40.0 % vs. 8.5 %, P = 0.003). In the refractory group, the 6 patients who did not undergo liver biopsy were those for whom liver biopsy was contraindicated because of severe hepatic deterioration (Table 5). HLA-DR phenotype distribution was similar between the non-refractory and refractory groups.

Discussion

HLA-DR4 is the most important immunogenetic factor responsible for type 1 AIH in Japan [20]. However, the frequency of HLA-DR4 in other countries ranges widely, from 3 % to 59 % [21–25]. In a study of Italian and North American type 1 AIH, HLA-DR4 was found to be less frequent in both Italian type 1 AIH and in control Italian individuals compared with North American counterparts [26]. Although HLA-DR4 is less frequent in Italy, the frequency of HLA-DR4 in the control population of Italy is also less than that of North American counterparts. Although HLA-DR4 was not associated with type1 AIH in Italy, the RR of HLA-DR4 for type 1 AIH in Italy (1.51) and North America (1.46) is quite similar. Therefore, the variation in the frequency of HLA-DR4 in type 1 AIH in different countries may partly depend on the variation in the frequency of HLA-DR4 in the background populations, and hence there is no global consensus on the association of HLA-DR4 and type 1 AIH.

A study on Japanese type 1 AIH revealed a very high occurrence of HLA-DR4 (>80 %) [27], warranting an extensive re-assessment of the distribution of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese AIH. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the significance of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese type 1 AIH patients. We found that HLA-DR4 alone was significantly associated with Japanese type 1 AIH, but the frequency was as low as 59.7 %. Meanwhile, HLA-DR4 is the most frequent DR antigen (41.7 %) in the normal Japanese population [16]. The RR of HLA-DR4 for type 1 AIH is 2.14, much higher than that for the Italian/North American-type 1 AIH. Other HLA-DR antigens, including HLA-DR13 and HLA-DR3 (DR17 or DR18) [28–31], were not associated with AIH in our study population.

We next examined the role of HLA-DR4 on the clinical features of type 1 AIH. HLA-DR4–positive AIH patients were young and had hypergammaglobulinemia without decreases in albumin levels or platelet count. Marked hypergammaglobulinemia might be a common feature of HLA-DR4–positive AIH in Japan [32]. According to age distribution, about 70 % of AIH patients who were <30 years old were reported to be HLA-DR4– negative [32]. In our patients, although the number of patients younger than 30 years old was relatively small, a tendency of decreasing HLA-DR4 in teens and children was observed.

Interestingly, the incidence of HLA-DR4 differed between elderly and young-to-middle-aged patients. The rate of HLA-DR4 in elderly patients was equal to that in normal subjects. Therefore, HLA-DR4 is not necessarily a risk factor contributing to the onset of AIH in elderly individuals. However, in North America, the frequency of DR4-positive AIH has been increasing in elderly patients, with a decline of DR3-positive AIH [12]. Meanwhile, in Japan, a higher frequency of advanced fibrosis without a change in HLA-DR status has been reported in elderly AIH patients [14]. In our study, the increase in advanced fibrosis in elderly AIH patients was limited to HLA-DR4 patients.

A critical difference between the present study and the earlier one might be the high proportion of elderly AIH patients in our study. Only 20 % of the patients were elderly in the past study, while 34.1 % of the patients in the current study were elderly. This can be attributed to the increase in older population in Japan and recent progress in the proper diagnosis of AIH onset in the elderly. In addition, when the results were compared with those of Caucasian type 1 AIH, HLA-DR3–positive AIH was negligible in the Japanese population.

HLA-DR4–positive elderly AIH patients exhibited prominent hyperglobulinemia, which is one of the characteristic features of typical AIH. In contrast, HLA-DR4–negative elderly AIH patients may exhibit atypical clinical results. Therefore, it is necessary to diagnose HLA-DR4–negative elderly AIH patients carefully.

In young-to-middle-aged AIH patients, the rate of HLA-DR4 was higher. The clinical characteristics were not different between HLA-DR4–positive and HLA-DR4–negative AIH. However, the number of AIH patients younger than 30 years was only 7 in our study. Therefore, precise characterization of AIH in young adults and/or children requires further research. For children or young adults, careful diagnosis of AIH by an experienced hepatologist is essential because differential diagnosis from other causes of liver damage, including chronic active Epstein–Barr virus infection, is difficult [33].

Finally, we examined the contribution of the HLA-DR antigen to the response to immunosuppressive therapy. Association of HLA-DR14 with a favorable response to corticosteroid therapy [34], better treatment response of HLA-DR4 than DR3 [11], lower occurrence of relapse after drug withdrawal and higher frequency of sustained remission in HLA-DR13 [30] have been reported. However, we did not find any differences in HLA-DR between refractory AIH and non-refractory AIH.

Patients with refractory AIH had severe deterioration of liver function. Therefore, we assumed that treatment efficacy was largely influenced by the functional deterioration of the liver at the time of starting therapy. Thus, proper diagnosis and therapy without delay are key factors for the successful treatment of AIH. Meanwhile, the effect of HLA-DR on treatment efficacy may be negligible; however, this cannot be conclusive because of the limited patient number in our study.

Conclusion

The HLA-DR4 antigen alone was associated with Japanese AIH. No other predisposing HLA-DR antigen was recognized in this study. The impact of HLA-DR4 on the features of AIH differed between elderly patients and younger patients. Treatment response was associated with the severity of liver disease but not with HLA-DR antigen. AIH refractory to immunosuppressive therapy was diagnosed in cases of severe liver dysfunction. Early recognition, proper diagnosis, and immediate start of immunosuppressive therapy are essential for favorable treatment outcome.

Abbreviations

- AIH:

-

Autoimmune hepatitis

- IAHG:

-

International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- TB:

-

Total bilirubin

- Alb:

-

Albumin

- PLT:

-

Platelet count

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- ANA:

-

Anti-nuclear antibodies

- AMA:

-

Anti-mitochondrial antibodies

- RR:

-

Relative risk

References

Boberg KM, Aadland E, Jahnsen J, Raknerud N, Stiris M, Bell H. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:99–103.

Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2009;29:273–85.

Czaja AJ, Freese DK, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479–97.

Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:54–66.

Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–38.

Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Autoantibodies and autoantigens in autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:339–52.

Czaja AJ, Manns MP. The validity and importance of subtypes in autoimmune hepatitis: a point of view. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1206–11.

Homberg JC, Abuaf N, Bernard O, Islam S, Alvarez F, Khalil SH, et al. Chronic active hepatitis associated with antiliver/kidney microsome antibody type 1: a second type of “autoimmune” hepatitis. Hepatology. 1987;7:1333–9.

Toda G, Zeniya M, Watanabe F, Imawari M, Kiyosawa K, Nishioka M, et al. Present status of autoimmune hepatitis in Japan—correlating the characteristics with international criteria in an area with a high rate of HCV infection. Japanese National Study Group of Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1207–12.

Donaldson PT, Doherty DG, Hayllar KM, McFarlane IG, Johnson PJ, Williams R. Susceptibility to autoimmune chronic active hepatitis: human leukocyte antigens DR4 and A1-B8-DR3 are independent risk factors. Hepatology. 1991;13:701–6.

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Santrach PJ, Moore SB. Significance of HLA DR4 in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1502–7.

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Distinctive clinical phenotype and treatment outcome of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in the elderly. Hepatology. 2006;43:532–8.

Al-Chalabi T, Boccato S, Portmann BC, McFarlane IG, Heneghan MA. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in the elderly: a systematic retrospective analysis of a large group of consecutive patients with definite AIH followed at a tertiary referral centre. J Hepatol. 2006;45:575–83.

Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Takaki A, Kobashi H, Sakaguchi K, Shiratori Y. Clinical features of Japanese elderly patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Intern Med. 2007;46:1945–9. Epub 2007 Dec 17.

Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Kobashi H, Yasunaka T, Ikeda F, Takaki A, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis with acute presentation in Japan. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:51–4.

HLA laboratory data [http://www.hla.or.jp]

Nakamura K, Yoneda M, Yokohama S, Tamori K, Sato Y, Aso K, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:490–5.

Fernandes NF, Redeker AG, Vierling JM, Villamil FG, Fong TL. Cyclosporine therapy in patients with steroid resistant autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:241–8.

Aqel BA, Machicao V, Rosser B, Satyanarayana R, Harnois DM, Dickson RC. Efficacy of tacrolimus in the treatment of steroid refractory autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:805–9.

Yoshizawa K, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, Ichijo T, Matsumoto A, Tanaka E, et al. Genetic analysis of the HLA region of Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2005;42(4):578–84.

Teufel A, Wörns M, Weinmann A, Centner C, Piendl A, Lohse AW, et al. Genetic association of autoimmune hepatitis and human leucocyte antigen in German patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5513–6.

Shankarkumar U, Amarapurkar DN, Kankonkar S. Human leukocyte antigen allele associations in type-1 autoimmune hepatitis patients from western India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:193–7.

Czaja AJ, Souto EO, Bittencourt PL, Cancado EL, Porta G, Goldberg AC, et al. Clinical distinctions and pathogenic implications of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in Brazil and the United States. J Hepatol. 2002;37:302–8.

Qiu DK, Ma X. Relationship between human leukocyte antigen-DRB1 and autoimmune hepatitis type I in Chinese patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:63–7.

Kosar Y, Kacar S, Sasmaz N, Oguz P, Turhan N, Parlak E, et al. Type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in Turkish patients: absence of association with HLA B8. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:185–90.

Muratori P, Czaja AJ, Muratori L, Pappas G, Maccariello S, Cassani F, et al. Genetic distinctions between autoimmune hepatitis in Italy and North America. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1862–6.

Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Kobashi H, Yasunaka T, Ikeda F, Takaki A, et al. Clinical features of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in adolescence and early adulthood. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:766–71.

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Moore SB. HLA DRB1*13 as a risk factor for type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in North American patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:522–8.

Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Moore SB. Clinical and HLA phenotypes of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis in North American patients outside DR3 and DR4. Liver Int. 2006;26:552–8.

Goldberg AC, Bittencourt PL, Mougin B, Cançado EL, Porta G, Carrilho F, et al. Analysis of HLA haplotypes in autoimmune hepatitis type 1: identifying the major susceptibility locus. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:165–9.

Bittencourt PL, Goldberg AC, Cançado EL, Porta G, Carrilho FJ, Farias AQ, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in susceptibility to autoimmune hepatitis types 1 and 2. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1906–13.

Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Takaki A, Onishi T, Okamoto R, Takaguchi K, et al. Human leukocyte antigen DR status and clinical features in Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:96–102.

Chiba T, Goto S, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Tanaka M, Fukai K, et al. Fatal chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection mimicking autoimmune hepatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:225–8.

Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Yatsuji H, Sezaki H, et al. Association of HLA-DR14 with the treatment response in Japanese patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2070–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the department of pathology at Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital and the Jikei University School of Medicine Katsushika Medical Center for providing the liver biopsy samples. We would like to thank editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YF designed the study, collected the data, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. TA drafted the manuscript. TS collected the data. HA collected the data and performed statistical analyses, CY and KF collected the data. AS performed histological examination. YA designed the study, collected the data, performed statistical analyses, drafted the manuscript, and led discussions with the coauthors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Furumoto, Y., Asano, T., Sugita, T. et al. Evaluation of the role of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 15, 144 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-015-0360-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-015-0360-9