Abstract

Objective

To examine primary care (PC) team members’ characteristics associated with video use at the Veterans Health Administration (VA).

Methods

VA electronic data were used to identify PC team characteristics associated with any video-based PC visit, during the three-year study period (3/15/2019-3/15/2022). Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models on repeated yearly observations were used, adjusting for patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics, and study year. We included five PC team categories: 1.PC providers (PCP), which includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, 2.Nurses (RN/LVN/LPN/other nurses), 3.Mental health (MH) specialists, 4.Social workers (SW), and 5.Clinical pharmacists (PharmD).

Population

54,494 PC care team members nationwide (61,728,154 PC visits; 4,916,960 patients), including 14,422 PCPs, 30,273 nurses, 2,721 MH specialists, 4,065 SWs, and 3,013 PharmDs.

Results

The mean age was 46.1(SD = 11.3) years; 77.1% were women. Percent of video use among PC team members varied from 24 to 84%. In fully adjusted models, older clinicians were more likely to use video compared to the youngest age group (18–29 years old) (example: 50–59 age group: OR = 1.12,95%CI:1.07–1.18). Women were more likely to use video (OR = 1.18, 95%CI:1.14–1.22) compared to men. MH specialists (OR = 7.87,95%CI:7.32–8.46), PharmDs (OR = 1.16,95%CI:1.09–1.25), and SWs (OR = 1.51,95%CI:1.41–1.61) were more likely, whereas nurses (OR = 0.65,95%CI:0.62–0.67) were less likely to use video compared to PCPs.

Conclusions

This study highlights more video use among MH specialists, SWs, and PharmDs, and less video use among nurses compared to PCPs. Older and women clinicians, regardless of their role, used more video. This study helps to inform the care coordination of video-based delivery among interdisciplinary PC team members.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

The rapid expansion of video-based telehealth services in primary care (PC) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] has provided new opportunities to examine a wide range of virtual care topics. Topics include patient and clinician satisfaction with services [8,9,10,11], advantages and disadvantages to implementation and use of telehealth services [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], patient and clinicians’ characteristics of telehealth use [20,21,22,23,24,25,26], disparities in access to video visits [27,28,29,30], and the extent to which telehealth can be incorporated in routine primary care [31,32,33,34,35]. Most of these small size studies have shown acceptability and satisfaction of video use among clinicians [8,9,10, 12, 13, 36], however, we are not certain the extent to which clinicians in PC use video-based services on large scale.

One important aspect of virtual care coordination among interdisciplinary, team-based PC settings is to have a better understanding about PC team members’ characteristics associated with the use of telehealth services. However, there is a knowledge gap about the extent to which different PC team members, such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, other nurses, mental health providers, clinical pharmacists, and social workers, exercise their preferences and actually utilize video-based care, as well as its association with other PC team characteristics (e.g., gender, age).

To address this gap, we conducted a national study of the provision of video-based care among interdisciplinary team-based PC team members. The Veterans Health Administration (VA) is an ideal place to conduct this study, since it has patient-aligned care teams with interdisciplinary team members in PC, which are similar to patient-centered medical models at various non-VA settings. Additionally, like many healthcare settings, access to telehealth services in PC increased dramatically at the VA immediately after onset of COVID-19 [5, 37,38,39,40,41]. Moreover, VA was an early adopter and a national leader [42] in telehealth, with over two decades of experience in video-based care [5].

In this study, we defined telehealth as using technology for a remote medical synchronous video encounter [43] and examined PC team members’ characteristics associated with use of video for primary care visits among different types of clinicians who care for the same patient population, after controlling for patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics. We also identified PC team members’ demographic characteristics, such as age and gender, that are associated with video use in PC.

Methods

Study design and study sample

This was a retrospective cohort study of VA interdisciplinary PC team members (e.g., physicians, nurses, social workers) from 12-months before and 24-months after the COVID-19 onset (March 16, 2019, through March 15, 2022) at 138 VA healthcare systems (i.e., VA medical center and associated community clinics) nationwide. We excluded two healthcare systems (one healthcare system that had transitioned to the Cerner Millennium EHR system and did not have data for the entire study period, and another healthcare system in a foreign country). VA patients who had at least one PC visit during the year prior to COVID-19 onset (March 16, 2019, through March 15, 2020) were included in the study. Characteristics of their PC visits (e.g., telehealth modality) during the 24-month period post COVID-19 onset (March 16, 2020, through March 15, 2022) and associated PC visit team members were identified. The study sample included 54,494 PC team members, 4,916,960 patients, and 61,728,154 PC visits. The study was part of an ongoing VA quality improvement effort approved by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System institutional review board, which deemed the study as non-human participants research and waived the informed consent requirements.

Study data

VA electronic records were used to compile patient-, PC team-, and healthcare system-level administrative, clinical, and utilization data. All data management and analyses were conducted within the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. Patient-level demographic and clinical characteristics, outpatient visit modality and its dates, and PC team member types were from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Rurality of patient residence was determined from the Geospatial Service Support Center geocoded enrollee files. PC team members’ demographic characteristics were obtained from the Personnel and Accounting Integrated Data payroll system. Lastly, healthcare system-level characteristics were obtained from the VHA Support Service Center.

Study measures

In this study, we examined video-based PC visits, which are a telehealth modality that allows synchronous communication between patients and PC team members, using a camera-enabled device. For each completed PC visit, clinic codes and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) modifier for synchronous telemedicine service were used to identify video visits (see Appendix A). For each patient, the most frequently seen PC team member for PC visits during the study year was assigned as the main clinician. Lastly, PC team members were assigned to a healthcare system in which they were most frequently associated during each study year. In the case of ties, PC team members were assigned to the healthcare system in which they provided their most recent encounter. It should be noted that even though there is a large amount of telephone use in VA primary care, the data accessible for this study could not decipher between short follow-up calls (e.g., lab test results), that are routinely conducted by primary care team members, and ‘real’ synchronous telephone visits (e.g., lets discuss your medication plan), that are comparable to synchronous video visits. As such, we focused on video-based care.

PC team characteristics included five age categories (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60+), gender (women, men), and five PC team type categories. PC team types were based on position titles and included: (1) Primary care providers (PCPs), which included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, (2) nurses, which included licensed vocational nurses, licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and other nurses, (3) mental health specialists (psychologists, psychiatrists, and mental health counselors), (4) clinical pharmacists, and (5) social workers.

Patient demographic characteristics known to be associated with video use [26] were included as covariates: patient’s age (18–44, 45–64, 65–75, 75+), gender (women or men), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other minority, unknown), marital status (married, divorced/widowed, single/never married), and the Charlson Comorbidity Index categories (0, 1, 2+) [44]. The rurality of patient’s residence (rural/highly rural, urban) is based on the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) classifications [45]. VA enrollment priority groups, which assigns patients to one of the eight priority groups, were also included in the analysis. This measure is based on military service-related disability, income, and other criteria and was further grouped into four categories: high disability, low/moderate disability, low income, and enrolled without special considerations [46]. High disability group refers to having > 50% service-related disability or catastrophically disabled. [47] Patients are deemed catastrophically disabled based on a VA clinical decision when they suffer from a severely disabling injury, disorder, or disease that permanently impairs their ability to perform activities of daily living to such an extent that they require personal or mechanical assistance to leave their home or bed, or constant supervision to prevent physical harm to themselves or others. [47] Low/moderate disability group includes 10–40% service-related disability or military exposures. Low income includes Veterans having household income below geographically adjusted threshold [48]. The enrolled without special considerations group refers to 0% service-related disability and co-pay requirement [47, 48].

Healthcare system characteristics included facility complexity and rurality [49]. Facility complexity was categorized as: low, medium, and high. This measure was defined by the VA Facility Complexity Model based on multiple criteria, which includes volume, patient risk, teaching and research status, breadth of physician specialties, and intensive care unit (ICU) level [50]. Rurality of the healthcare system (rural vs. urban) was designated based on rurality of the majority of the associated hospital and clinics, following the RUCA classifications [45]. Medical centers and clinics were categorized as rural if their RUCA classifications were rural, highly rural, or insular.

Statistical analyses

For bivariate analysis, unadjusted percentages of any video use were calculated by PC team characteristics (age categories, gender, and provider type) for each study year (one year before COVID-19 onset, one year after COVID-19 onset, and two years after COVID-19 onset). For multivariate analysis, PC team-level predictors of any video use were examined after controlling for study year, patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics, using multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models. Random intercepts for patients and PC team were used to account for patient/PC team clustering.

All statistical tests were two-sided at the significance threshold of p < 0.05. Data were analyzed in Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) from August 2022 to February 2023.

Results

The study included 14,422 (26.5%) PCPs, 30,273 (55.6%) nurses, 2,721(5.0%) mental health specialists, 3,013 (5.5%) clinical pharmacists, and 4,065 (7.5%) social workers. Interdisciplinary PC team members had a mean age of 46.1 years [SD 11.3], and 77.1% were women (Table 1).

In unadjusted analyses, the percentages of VA PC team members with any video visit ranged from 24.0 to 48.8% for one year before COVID-19, followed by 69.9–82.5% during the first COVID-19-year, and then 65.9–83.8% during the second COVID-19-year. PC team members in the youngest age category used video the least compared to PC team members in the oldest age category (24.0% for 18–29 years old vs. 34.6% for 60 + years old) one year before COVID-19. The same pattern persisted during the first and second COVID-19-years (see Table 2). A higher proportion of men had at least one video-based visit compared to women PC team members (37.6% men vs. 32.8% women) before COVID-19. However, during the first COVID-19-year, women had slightly more video-based visits (74.4% men vs. 75.9% women), followed by a reversal, where a higher proportion of men had video-based visits (73.7% men vs. 68.1% women) in the second COVID-19-year. Before COVID-19, PCPs (48.8%) and mental health specialists (42.1%) had the highest percent with any video-based visit, followed by clinical pharmacists (38.7%), social workers (26.5%) and nurses (24.8%). In the first COVID-19-year, video use increased sharply for all PC team types. However, in the second COVID-19-year, video use increased for PCPs, mental health specialists, and social workers, but it decreased for nurses and clinical pharmacists (see Table 2).

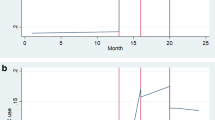

After adjusting for patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics and study year, multilevel logistic regression models of video-based care indicated that older PC team members were more likely to have any video-based visit compared to the youngest age group category (18–29 years old) (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.18 for 30–39 years old; OR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.07–1.19 for 40–49 years old; OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07–1.18 for 50–59 years old; p’s < 0.001) (see Fig. 1).

Adjusted odds ratios for primary care (PC) video-based visits by PC team characteristics using multilevel mixed effects, logistic regression. Note The regression model adjusted for patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics (patient: socio-demographic and clinical characteristics; healthcare system: facility complexity and rurality), as well as indicators for regional networks of care and study year. Abbreviations Odds ratio (OR); 95% confidence interval (95% CI). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

In fully adjusted models, however, women were more likely to use video (OR = 1.18, 95% CI:1.14–1.22; p < 0.001) compared to men. Regarding PC team types, mental health specialists (OR = 7.87, 95% CI: 7.32–8.46; p < 0.001), social workers (OR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.41–1.61; p < 0.001), and clinical pharmacists (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.09–1.25; p < 0.001) were found to use more video compared to PCPs. Nurses were found to use less video (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.62–0.67; p < 0.001) compared to PCPs. For complete regression results with odds ratios and 95% CI for patient-, PC team- and healthcare system-level characteristics see Table 3.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first national multi-year study to examine the association between healthcare providers’ characteristics and real-time synchronous video visits among interdisciplinary PC teams. Previous research on provider characteristics associated with the use of video-based care mainly focused on providers’ preferences of using video-based care [9, 14, 16,17,18, 22], their satisfaction with video-based care [8,9,10,11], and the benefits and challenges of using video-based care [12, 13, 15,16,17, 19], often using small sample sizes. Consistent with prior research [23], PC team member type, such as PC providers, nurses, and mental health specialists, was an important predictor of video use. Similar to previous findings, after controlling for relevant patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics, mental health specialists, social workers, and clinical pharmacists in PC were more likely, while nurses were less likely, to use video compared to PC providers (such as physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants). Identification of what types of PC team members are more likely to provide video-based care illustrates “exercised preference” – i.e., who is actually willing to conduct video visits. These findings can help guide the care coordination of video visits among PC team members. Given that mental health specialists, social workers, and clinical pharmacists do not conduct physical examinations during clinical visits, it is not surprising that they were more likely to use video-based care compared to PCPs. Conversely, it is not surprising that nurses were less likely to use video compared to PCPs, given that nurses in PC settings are often tasked with checking patient’s vital signs (during in-person/clinic visits), triaging patients (via phone calls), or sharing lab results (via phone calls). These findings, like those in previous studies [51, 52], further illustrate that the appropriateness of a video-based PC visit depends on the types of services that are being provided.

Regarding provider demographic characteristics, the study illustrated that older providers were more likely to use video compared to the youngest providers (18–29 years old). Age might be a proxy for clinical experience. Even though younger PC members are perhaps more tech-savvy, older PC team members might have more clinical experience and established patient panels and perhaps have more flexibility in teleworking options or administrative positions, where video visits become more feasible. The study findings also illustrated that women were more likely to use video compared to men. This finding may be because women having more family obligations at home, where teleworking may be a viable option for these clinicians. In addition to provider characteristics, providers try to meet their patients where they are at by being flexible with the type of visit (in-person or virtual) they offer or schedule. Patient’s preferences, and/or other factors (such as lack of transportation), may influence whether the patient is able to attend in-person or video visits.

The major strengths of this study are the use of national data and identification of PC team characteristics of video-use among interdisciplinary primary care team members, after controlling for the effects of patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics. However, this study has several limitations. First, the scope of PC team characteristics is limited to three variables: PC team type, age, and gender, which were accessed using electronic administrative data. The gender variable included men or women and did not include other gender identities (e.g., non-binary, transgender). Future studies might have opportunities to include additional data on patients and providers who identify with other gender identities. There are many other PC team characteristics that could impact video use, such as length of employment at the VA, clinical experience, and provider preference or comfort. Unfortunately, additional PC team variables were not available in these records. Therefore, more research should be conducted to assess the association of additional clinician characteristics with video use. Second, since the data available for this study could not decipher between short follow-up telephone visits vs. ‘real’ synchronous telephone visits, this study only focused on video-based care. Furthermore, provider characteristics related to telephone care are likely distinct from those associated with video-based care given that telephone-based care has been commonplace for a longer time and relies on near ubiquitous phone technology with minimal requirements. Whereas video-based care has experienced a surge in adoption recently following the COVID19 pandemic and still faces challenges for more widespread adoption. Third, generalizability of the study findings from VA to non-VA healthcare settings might be limited. However, recent COVID-19 telehealth waivers have increased non-VA healthcare providers’ video-based care capability. Therefore, today there are more similarities than ever between VA and non-VA telehealth services. As such, study findings may still be applicable to non-VA clinical settings and contribute to the growing evidence base surrounding provider characteristics associated with video use.

Conclusion

In addition to patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics, it is also important to consider PC team members’ characteristics that are associated with video telehealth use. This study highlights the significant association of PC team type, age, and gender with video use, after taking into account patient- and healthcare system-level characteristics. This fills in the knowledge gap on clinician characteristics of video use, using national data. By focusing on PC team characteristics, this study helps to inform the care coordination of video-based visits among interdisciplinary primary care team members.

Data availability

To protect study participant privacy, the study data cannot be shared openly.

References

Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4.

Keesara S, Jonas A, Schulman K. COVID-19 and health care’s digital revolution. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):e82. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2005835.

Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer DM, Barnett ML, Bender JA. Rapidly converting to virtual practices: outpatient care in the era of COVID-19. NEJM Catalyst. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0091.

Joshi AU, Lewis RE. Telehealth in the time of COVID-19. Emerg Med J. 2020;37:637–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2020-209846.

Heyworth L, Kirsh S, Zulman D, Ferguson JM, Kizer KW. Expanding access through virtual care: The VA’s early experience with COVID-19. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2020.

Reddy A, Gunnink E, Deeds SA, et al. A rapid mobilization of ‘virtual’ primary care services in response to COVID-19 at Veterans Health Administration. Healthc (Amst). 2020;8(4):100464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100464.

Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–81. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2003539.

Saiyed S, Nguyen A, Singh R. Physician perspective and key satisfaction indicators with rapid telehealth adoption during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(11):1225–34. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0492.

Gold KJ, Laurie AR, Kinney DR, Harmes KM, Serlin DC. Video visits: family physician experiences with uptake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):207–10. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.613099.

Chang PJ, Jay GM, Kalpakjian C, Andrews C, Smith S. Patient and provider-reported satisfaction of cancer rehabilitation telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. PM R. 2021;13(12):1362–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12552.

Bate NJ, Xu SC, Pacilli M, Roberts LJ, Kimber C, Nataraja RM. Effect of the COVID-19 induced phase of massive telehealth uptake on end-user satisfaction. Intern Med J. 2021;51(2):206–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.15222.

Breton M, Sullivan EE, Deville-Stoetzel N, et al. Telehealth challenges during COVID-19 as reported by primary healthcare physicians in Quebec and Massachusetts. BMC Fam Pract. 2021a;22(1):192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-021-01543-4.

Breton M, Deville-Stoetzel N, Gaboury I, et al. Telehealth in primary healthcare: a portrait of its rapid implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc Policy. 2021b;17(1):73–90. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2021.26576.

Goldberg EM, Lin MP, Burke LG, Jiménez FN, Davoodi NM, Merchant RC. Perspectives on telehealth for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic using the quadruple aim: interviews with 48 physicians. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02860-8.

Goldberg EM, Jiménez FN, Chen K, et al. Telehealth was beneficial during COVID-19 for older americans: a qualitative study with physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(11):3034–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17370.

Gomez T, Anaya YB, Shih KJ, Tarn DM. A qualitative study of primary care physicians’ experiences with telemedicine during COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Suppl):S61–70. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200517.

Johnson C, Dupuis JB, Goguen P, Grenier G. Changes to telehealth practices in primary care in New Brunswick (Canada): a comparative study pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0258839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258839.

Chan-Nguyen S, O’Riordan A, Morin A, et al. Patient and caregiver perspectives on virtual care: a patient-oriented qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2022;10(1):E165–72. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20210065.

DeHart D, King LB, Iachini AL, Browne T, Reitmeier M. Benefits and challenges of implementing telehealth in rural settings: a mixed-methods study of behavioral medicine providers. Health Soc Work. 2022;47(1):7–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlab036.

Desborough J, Dykgraaf SH, Sturgiss E, Parkinson A, Dut G, Kidd M. What has the COVID-19 pandemic taught us about the use of virtual consultations in primary care? Aust J Gen Pract. 2022;51(3):179–83.

Scott A, Bai T, Zhang Y. Association between telehealth use and general practitioner characteristics during COVID-19: findings from a nationally representative survey of Australian doctors. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046857. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046857.

Demirgan S, Kargı Gemici E, Çağatay M, et al. Being a physician in coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and alternative health care service: Telemedicine: prospective survey study. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(12):1355–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0546.

Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, et al. Implementation of telehealth services at the VA during COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9):e29429. https://doi.org/10.2196/29429. https://formative.jmir.org/2021/9/e29429.

Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2031640.

Stevens JP, Mechanic O, Markson L, O’Donoghue A, Kimball AB. Telehealth use by age and race at a single academic medical center during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e23905.

Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2021;28(3):453–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa284.

Adepoju O, Liaw W, Chae M, et al. COVID-19 and telehealth operations in Texas primary care clinics: disparities in medically underserved area clinics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;32(2):948–57. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2021.0073.

Jaffe DH, Lee L, Huynh S, Haskell TP. Health inequalities in the use of telehealth in the United States in the lens of COVID-19. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23(5):368–77. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2020.0186.

Webber EC, McMillen BD, Willis DR. Health care disparities and access to video visits before and after the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a patient survey in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0126.

Hirko KA, Kerver JM, Ford S, et al. Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for rural health disparities. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2020;27(11):1816–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa156.

Uscher-Pines L, Martineau M, RAND, Corporation. Telehealth after COVID-19: Clarifying policy goals for a way forward. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1089-1.html. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Thomas EE, Haydon HM, Mehrotra A, et al. Building on the momentum: sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28(4):301–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20960638.

Knierim K, Palmer C, Kramer ES, et al. Lessons learned during COVID-19 that can move telehealth in primary care forward. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Supplement):S196–202. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200419.

Jabbarpour Y, Jetty A, Westfall M, Westfall J. Not telehealth: which primary care visits need in-person care? J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(Supplement):S162–9. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200247.

Olayiwola JN, Magaña C, Harmon A, et al. Telehealth as a bright spot of the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the virtual frontlines (Frontweb). JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e19045.

Cannedy S, Leung L, Wyte-Lake T, et al. Primary care team perspectives on the suitability of telehealth modality (phone vs video) at the Veterans Health Administration. J Prim Care Community Health. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231172897.

Darkins A. The growth of telehealth services in the Veterans Health Administration between 1994 and 2014: a study in the diffusion of innovation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:761–8.

Veazie S, Bourne D, Peterson K et al. Evidence Brief: Video Telehealth for Primary Care and Mental Health Services. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2019 Feb. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538994/. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Elliott V. Congressional Research Report. Department of Veterans affairs (VA): a primer on telehealth. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2019.

Spelman JF, Brienza R, Walsh RF, et al. A model for rapid transition to virtual care: VA Connecticut primary care response to COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3073–6.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Video Connect. https://mobile.va.gov/app/va-video-connect. Accessed July 10, 2023.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Office of Connected Care. https://connectedcare.va.gov/. Accessed July 10, 2023.

NEJM Catalyst. What is telehealth? NEJM Catal. 2018;4(1).

Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(1):8–35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521288.

US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Support Service Center (VSSC). http://vssc.med.va.gov/VSSCAgreements/Default.aspx?locn=vssc.med.va.gov. Accessed May 2023.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Priority Groups. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Criteria for a Catastrophically Disabled Determination for Purposes of Enrollment. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/02/22/2013-04134/criteria-for-a-catastrophically-disabled-determination-for-purposes-of-enrollment. Accessed April 2024.

Means Test and Geographic Thresholds. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/02/01/E7-1657/means-test-and-geographic-thresholds. Accessed April 2024.

Jacobs J, Ferguson MJ, Campen JV, et al. Organizational and external factors associated with video telehealth use in the Veterans Health Administration before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemed J E Health. 2022;28(2):199–211. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0530.

Veterans Health Administration Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing (OPES). Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Facility Complexity Model. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2020.

Gray C, Wray C, Tisdale R, Chaudary C, Slightam C, Zulman D. Factors influencing how providers assess the appropriateness of video visits: Interview study with primary and specialty health care providers. J Med Internet Res. 2022; 24;24(8):e38826. https://doi.org/10.2196/38826

Segal JB, Dukhanin V, Davis S. Telemedicine in primary care: qualitative work towards a framework for appropriate use. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(3):507–16. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2022.03.210229.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: This material was supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Connected Care (XVA 65-127), VA Health Services Research & Development (PPO 21-247), and the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Funding

This study was funded by the Veterans Health Administration (VA) Office of Connected Care (XVA 65–127, MPI: Der-Martirosian & Leung). Dr. Leung is supported by Career Development Award IK2 HX002867 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.D.M and L.L. wrote the main manuscript. C.Y., C.H., K.C. and J.F. conducted the data analyses. W.N.S. conducted the statistical modeling and interpreted the study findings. C.Y. prepared Table 1, and 2; Fig. 1, and supplementary materials. M.C and L.H. conceptualized the study. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was part of an ongoing VA quality improvement effort approved by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System institutional review board, which deemed the study as non-human participants research and waived the informed consent requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Der-Martirosian, C., Yoo, C.K., Steers, W.N. et al. Primary care team characteristics associated with video use: a retrospective national study at the Veterans Health Administration. BMC Prim. Care 25, 333 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02565-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02565-4