Abstract

Background

People with dual diagnosis die prematurely compared to the general population, and general practice might serve as a setting in the healthcare system to mend this gap in health inequity. However, little is known about which interventions that have been tested in this setting.

Aim

To scope the literature on interventions targeting patients with dual diagnosis in a general practice setting, the outcomes used, and the findings.

Design and setting

A scoping review of patients with dual diagnosis in general practice.

Methods

From a predeveloped search string, we used PubMed (Medline), PsychInfo, and Embase to identify scientific articles on interventions. Studies were excluded if they did not evaluate an intervention, if patients were under 18 years of age, and if not published in English. Duplicates were removed and all articles were initially screened by title and abstract and subsequent fulltext were read by two authors. Conflicts were discussed within the author group. A summative synthesis of the findings was performed to present the results.

Results

Seven articles were included in the analysis. Most studies investigated integrated care models between behavioural treatment and primary care, and a single study investigated the delivery of Cognitive Behavioral treatment (CBT). Outcomes were changes in mental illness scores and substance or alcohol use, treatment utilization, and implementation of the intervention in question. No studies revealed significant outcomes for patients with dual diagnosis.

Conclusion

Few intervention studies targeting patients with dual diagnosis exist in general practice. This calls for further investigation of the possibilities of implementing interventions targeting this patient group in general practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well known that patients with severe mental illness (SMI) die up to 10–20 years before the general population [1]. Moreover, studies have shown that when mental illness is accompanied by a substance use disorder (SUD), the mortality gap increases further [2, 3]. This simultaneous presence of both severe mental illness and SUD is referred to as dual diagnosis or co-occurring disorders [4] and occurs in approximately 30% of all patients diagnosed with SMI [5]. There is no official definition of dual diagnosis, and dual diagnosis is not coded in the international coding system (ICD-10), however, the overall understanding of the term is that patients are affected by at least one mental illness and substance abuse disorder at the same time [4].

Having a dual diagnosis is associated with several adverse outcomes such as a higher incidence of recurrence of mental illness [6], increased hospitalization and readmissions [7], infections such as HIV [8] and Hepatitis C [9], and increased mortality [2, 3]. The lower average life expectancy can, in addition to suicidal behaviour and overdose, be largely attributed to an increased risk of several chronic health conditions [3, 6, 10,11,12,13,14], with cardiovascular disorders reported as being the greatest risk [15]. Even though patients with a dual diagnosis evidently need treatment for somatic diseases, research shows that the quality of the treatment provided fluctuates. There are several examples of this patient group being disregarded for their physical health problems, or the patients’ physical symptoms being misinterpreted by the health personnel as mental symptoms [16, 17].

In line with increased awareness of the patient group, the high prevalence of SUD among patients with SMI, and the complex issues associated with the diagnosis, the primary healthcare contact points for these patients vary across healthcare systems and contexts. However, primary care generally serves as the patient’s first point of contact with the healthcare system. Because general practitioners (GPs) in most cases act as gatekeepers to the secondary system, and thus potentially facilitates early discovery of disorders, their role in the healthcare system is essential for referring patients and managing their care. General practice could play a pivotal role in coordinating treatment for patients with dual diagnosis, and furthermore the GP is important in the detection, assessment, treatment, follow-up, and continuity of treatment of somatic diseases – the primary cause of premature death in this patient group [17, 18]. From studies investigating the path or journey for people suffering from dual diagnosis in the healthcare system, we know that patients with dual diagnosis often fall between chairs [19]. Despite extensive research in the general field of dual diagnoses, less is known about the role of general practitioners in coordinating care, detecting diseases, or treating patients with dual diagnosis, and what interventions has been performed to improve the healthcare delivery in this setting. It is also unclear, which effect measures have been examined in evaluations of interventions, and whether they relate to contact, follow-up, or treatment goals [18, 20].

Aim

The study investigated the literature on interventions in a general practice setting targeting patients with dual diagnosis (co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder), and aimed to answer the following questions:

-

1.

Which interventions targeting patients with dual diagnosis have been tested in a general practice setting?

-

2.

Which outcomes did the studies use to evaluate the interventions, and what were the primary findings?

Methods

This scoping review was assembled by the methods developed by Arksey and O’Malley [21]. This type of review is well suited to highlight significant gaps in the evidence [22]. No review protocol has been published previous to this study.

Data sources, search strategy, and inclusion criteria

We used the electronic databases PubMed (Medline), PsychInfo, and Embase to identify scientific articles on interventions aimed at patients with co-occurrence of severe mental illness and substance use in general practice. The specific search string and strategy are shown in appendix 1. We defined severe mental illness as either a diagnosis with depression of moderate or severe degree, bipolar affective disorder, or schizophrenia. Substance use disorder was defined as any harmful use of either drugs or alcohol. Additionally, the article should evaluate an intervention or initiative linked to general practice or primary care. We excluded studies that included patients under 18 years of age, and studies that were not published in English. The search was not limited to study type, date of publication, or a specific country. A combination of MeSH terms, keywords, free text search, as well as related terms, were used with Boolean operators (AND, OR). Each search was adapted to the specific requirements of the individual database, where the search string was divided into blocks of dual diagnosis (block 1), general practice (block 2), and intervention (block 3). The block descriptions and the final search string can be found in Appendix 1. The search was performed on April 22nd, 2022 and an update was performed on February 1st 2024. We found no additional articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria in the updated literature search.

Study selection

The studies identified in the final literature search were initially exported to the Endnote reference database to remove duplicates [23]. Afterwards, we imported the references to Covidence screening program [24]. The initial article sample was screened twice by four researchers (BC read all abstracts, and all abstracts were also screened by one of the co-authors MN, KT, and AM). Articles were selected for full-text review, if they met the following criteria:

1) Patients with dual diagnosis (understood as co-occurring severe mental illness, as defined in the above section, and substance use of either drugs or alcohol), 2) Adults above 18 years, and 3) Article should include an evaluation of one or more interventions situated in general practice. Any conflicts regarding inclusion of articles during the initial screening process were discussed and resolved before moving on to full text screening. The full text screening was performed by BC and KT. Conflicts were discussed and resolved between all four researchers.

Data extraction and synthesis

From the included studies, we extracted data on study design, participants, definition of dual diagnosis, and description of intervention content, outcome measures, and overall study findings described in the study. This task was performed by AM and KT and verified by the remaining authors. Afterwards, we described the design and content of the interventions in the included studies, and listed the outcome measures and overall study findings in a non-systematic narrative summary in the results section.

Results

Search and study selection

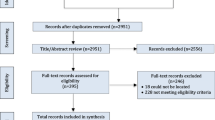

The literature search in three databases yielded 1,879 articles after excluding duplicates. Our screening of both abstracts and titles, showed 172 articles were eligible for full-text review. Six articles met the final criteria and were included in the synthesis and one article was found in the reference list of one of the articles. The complete study selection and exclusion process is presented in Fig. 1. The general characteristics of the included articles are reported in Table 1. As described in Table 1, the studies from Oslin et al. and Bartels et al. origin from the same research project as well as the studies from Padwa et al. and Urada et al. All studies were conducted in the United States. In the updated literature search, we identified two studies, where it was unclear whether the intervention was based in general practice or a primary care setting. These studies were not included in the final synthesis.

Description of interventions

Overall, the identified studies can be divided into interventions testing (1) integrated care of mental disorders, substance use, and/or primary care [25,26,27,28,29,30], or (2) delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [31]. The integrated care models differ somewhat in the locus of the intervention. Park et al. [29] tested a Chronic Care management model with a specific focus on substance dependance treatment compared to usual primary care. The PRISM-E study (Bartels and Oslin et al. [25, 27]) had co-located mental- and substance use treatment which was compared to enhanced referral care offering similar treatment in a separate location. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model was tested by Felleman et al. [26] and entailed mental health services embedded within the primary care clinic. “Project Care” (Padwa and Urada et al. [28, 30]) introduced onsite screenings, treatment, referral, and case management of mental and substance use disorders. One study did not test integrated care but different ways of delivering CBT either face-to-face or telephone administered [31].

Investigated outcomes and findings

The outcomes used for assessing the interventions can broadly be categorized into four different areas related to (1) mental health assessment, (2) substance and/or alcohol use assessment, (3) healthcare utilization or treatment engagement, and (4) implementation of the intervention.

We divided outcomes related to mental health into assessments regarding either changes in depression- or anxiety levels. To assess changes in depression level the studies used the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) [29, 31] and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [31] as psychometrics. Receiving antidepressants and meeting criteria for major depression were also used to assess changes in depression level. Anxiety severity was measured by using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [29]. These outcomes were used to assess an integrated care model (CCM) [29] versus usual primary care and face-to-face CBT [31] versus telephone administered CBT. None of the studies yielded significant differences in patients with dual diagnosis.

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [29], the Short Inventory of Problems for Alcohol and Drug Use (SIP) [29], the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) [31], and quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption [27], were used to assess changes in substance- and alcohol use. No significant differences for any outcome were found for integrated care interventions on substance or alcohol use for patients with dual diagnosis. Looking at CBT, Kalatapapu et al. [31] did not find a significant difference between the groups having either face-to-face or telephone delivered CBT, however a significant decrease in alcohol use from baseline to end of study was detectable in both groups. It should however be mentioned, that around 25% of the study population dropped out of treatment, and a sub-analysis revealed that these individuals were more likely to meet the criteria for depression remission [31].

Healthcare utilization was assessed by either a count number of contact points with different healthcare facilities [26, 29], attendance as showing up for a scheduled appointment, or treatment drop-out [25, 26, 31]. None of the studies showed any significant differences in outcomes regarding healthcare utilization. The CBT study by Kalapatapu et al. [31] showed a discontinuation of treatment for 25% of patients, who were more prone to fulfill remission criteria for depression.

Implementation outcomes were reported in relation to Project Care (which was investigated in two of the included studies) [28, 30]. Regarding the integrated model in Project Care, The Behavioral Health Integration in Medical Care (BHIMC) tool was used to assess the capacity to deliver integrated services, employee’s perceptions of the model were assessed in a survey, and moreover contextual factors which impacted implementation were assessed qualitatively. Overall, Project Care was well received by employees, but some issues concerning the flow of information in the integrated model (mostly from primary care to behavioral health services) were identified, which yielded some difficulties in implementing an integrated model in a primary care setting.

Target population

Scoping the literature, we detected major differences in the definitions of dual diagnosis in the identified studies, and no interventions were specifically targeted patients with dual diagnosis in our understanding as co-occurring SMI (severe depression, psychotic or bipolar disorders) and SUD.

Regarding the definition of SMI, three of the identified interventions were tested primarily on patients with depression [26, 29, 31]. The study by Park et al. furthermore included patients with PTSD [29]. In the remaining studies mental health disorders were defined in broader terms; Mental health conditions and Mental health problems respectively [25, 27, 28, 30].

The identified studies also used different definitions of SUD. SUD was defined either by using screening tools, having a diagnosis with SUD in a medical record, or by assessing the regularity or amount of alcohol or drug consumption. The studies by Bartels et al., Oslin et al. and Kalapatu et al. only included patients with problematic or at-risk alcohol consumption [25, 27, 31]. SUD in Felleman et al., Padwa et al. and Urada et al. were described as “substance use conditions” however, these were not specified further [26, 28, 30].

Discussion

In this article, we have performed a scoping review of the literature investigating interventions in general practice targeting patients with dual diagnosis. We included seven studies in our narrative synthesis. The identified interventions consisted primarily of different types of integrated treatment models in various organization modes and combinations plus one study focusing on the delivery of CBT treatment. A range of different outcomes was used to evaluate the interventions, where psychometrics primarily were used for assessing depression and anxiety levels, and consumption measures were used to assess SUD. No significant differences were found in mental health or SUD improvements. Furthermore, two of the identified studies evaluated intervention implementation of an integrated care model and found implementation feasible, however, the information flow from primary care to behavioural health services could be improved.

From our analysis of the literature regarding interventions targeting patients with dual diagnosis in a general practice context, we have identified a tremendous gap. There could be several reasons for this. Of the seven studies we identified, none evaluated interventions that directly targeted patients with SMI and co-occurring SUD. The primary mental disorder was major depression, and we found no studies that included either affective bipolar disorder or psychotic disorders. Moreover, the most common SUD were alcohol use disorder or at-risk drinking. Only one study included drug use in their definition of SUD. This lack of interventions targeting populations with more severe disorders could be a result of our focus on the general practice setting. One could argue that general practice does not carry the primary treatment responsibility for this patient population – particularly not the patients who are severely mentally ill and are concurrently using substances actively. These patients are, in most parts (in most countries), treated and tended to in the psychiatric system, who also diagnose SMI, and prescribe- and regulate psychotropic drug prescriptions. This might also be the underlying reason that no pharmaceutical treatment interventions were identified in the review, since medication prescriptions related to the treatment of SMI often is prescribed and administered in the secondary healthcare sector. However, general practitioners (GPs) do play a pivotal role, when it comes to identifying risk factors in the initial stages of disease development (including identification of mental illnesses and substance use disorders) [32] and coordinating care across healthcare sectors, and continuity of care with a regular GP have been found to lower acute hospital admissions and mortality in patients in general [33]. Since this population is particularly vulnerable towards chronic somatic comorbidities, the findings from our study could call for novel research interventions on dual diagnosis in general practice in other contexts.

Limitations

The purpose of the study was to identify interventions evaluated in a general practice setting. Since we only ended up including seven studies, it might be relevant to scope the broader literature by including other study designs. By including a more explorative study design, we could potentially gain a deeper understanding of the landscape of dual diagnosis within general practice. We only included studies published in English, and thus we might have overlooked findings from publications outside the Global North. Moreover, the definition of dual diagnosis has been discussed in the literature. The concept of dual diagnosis was introduced in the 1980s [4], but today there is no common diagnostic criterion for the condition. Hence, there may be terms for dual diagnosis that were not covered in our search string, cf. appendix.

Contrary to the concept of dual diagnoses, there are many well-defined terms for general practice, however, large differences exist globally regarding healthcare structures. Surprisingly, all interventions included for analysis were situated in the United States. Since the US has a unique healthcare system based on insurance and, at large, self-payment structures, transferring the results to other healthcare systems organized differently could prove to be difficult. Lastly, our definition of interventions in the study is somewhat narrow. We only included interventions tested or evaluated, however we could have broadened the scope of the study to include study protocols, programs, initiatives, or treatments. This might have contributed to a broader perspective on the landscape of general practice and dual diagnoses. Overall, this has several implications, that one may have both overlooked and included articles that should not have been included in the review, as well as potentially not having a complete picture of the interventions that are in the field.

Conclusion

Only seven intervention studies targeting patients with dual diagnosis in the setting of general practice were found in this scoping review. This finding could suggest a lack of research within this area and points towards a potential for future investigations and testing of interventions targeting this vulnerable patient population in a general practice setting.

Data availability

N/A.

Abbreviations

- SMI:

-

Severe mental illness

- SUD:

-

Substance Use Disorder

- CBT:

-

Cognitive Behavioral Treatment

- GP/GPs:

-

General practitioner/General practitioners

References

Chang CK, Hayes RD, Perera G, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019590. PubMed PMID: 21611123; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3097201. eng.

Hjorthøj C, Østergaard ML, Benros ME, et al. Association between alcohol and substance use disorders and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: a nationwide, prospective, register-based study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):801–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00207-2. PubMed PMID: 26277044; eng.

Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055176. PubMed PMID: 23372832; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3555866. eng.

Hryb K, Kirkhart R, Talbert R. A call for standardized definition of dual diagnosis. Psychiatry. 2007;4:15–6.

Toftdahl NG, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Prevalence of substance use disorders in psychiatric patients: a nationwide Danish population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(1):129–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1104-4. PubMed PMID: 26260950; eng.

Volkow ND. Substance use disorders in schizophrenia–clinical implications of comorbidity. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):469–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp016. PubMed PMID: 19325163; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2669586.

Pourat N, Chen X, Lee C, et al. Improving Outcomes of Care for HRSA-Funded Health Center patients who have Mental Health conditions and Substance Use disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2020;47(2):168–88. PubMed PMID: 31214934.

Stoskopf CH, Kim YK, Glover SH. Dual diagnosis: HIV and mental illness, a population-based study. Community Ment Health J. 2001;37(6):469–79. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1017577827658. PubMed PMID: 11504140; eng.

Roncero C, Buch-Vicente B, Martín-Sánchez ÁM, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with chronic mental disorders: the relevance of dual disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2022.06.005. PubMed PMID: 35780956; eng spa.

Chesher NJ, Bousman CA, Gale M, et al. Chronic illness histories of adults entering treatment for co-occurring substance abuse and other mental health disorders. Am J Addict. 2012;21(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00196.x. PubMed PMID: 22211340; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3629909.

Hannerz H, Borgå P, Borritz M. Life expectancies for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. Public Health. 2001;115(5):328–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ph.1900785. PubMed PMID: 11593442; eng.

Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Gasse C. Chronic somatic comorbidity and excess mortality due to natural causes in persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e24597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024597. PubMed PMID: 21935426; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3173467. eng.

Correll MDEH, Bobes CU. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014. x. PubMed PMID: 21379357; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3048500. eng.

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20252. PubMed PMID: 26407790; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4592657. eng.

Gardner-Sood P, Lally J, Smith S, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in people with established psychotic illnesses: baseline data from the IMPaCT randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2015;45(12):2619–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715000562. PubMed PMID: 25961431; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4531468. eng.

Lawrence D, Kisely S. Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 Suppl):61–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359786810382058. PubMed PMID: 20923921; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2951586. eng.

Lawrence R. Primary care and dual diagnosis. In: GH R, editor. Dual diagnosis nursing. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 140–9.

Thylstrup B, Johansen KS, Sønderby L. Treatment effect and recovery — dilemmas in dual diagnosis treatment. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;26(6):552–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600601.

Kêdoté MN, Brousselle A, Champagne F. Use of health care services by patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Ment Health Subst Use. 2008;1(3):216–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17523280802274886. PubMed PMID: 27239226; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4882163. eng.

Johansen KS. Treatment of dual diagnosis in Denmark. Qualitative Stud. 2018;5(2):125–39. https://doi.org/10.7146/qs.v5i2.104500.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005 2005/02/01;8(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Alsuhaibani R, Smith DC, Lowrie R, et al. Scope, quality and inclusivity of international clinical guidelines on mental health and substance abuse in relation to dual diagnosis, social and community outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03188-0. PubMed PMID: 33892659; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8066498.

Team TE. EndNote [64 bit]. EndNote X9. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

Innovation VH. Covidence systematic review software Melbourne, Australia. Available from: www.covidence.org.

Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1455–62. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1455. PubMed PMID: 15285973; eng.

Felleman BI, Athenour DR, Ta MT et al. Behavioral health services influence medical treatment utilization among primary care patients with comorbid substance use and depression. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20(4):415 – 26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-013-9367-y. PubMed PMID: 23744107; eng.

Oslin DW, Grantham S, Coakley E, et al. PRISM-E: comparison of integrated care and enhanced specialty referral in managing at-risk alcohol use. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):954–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.954. PubMed PMID: 16816279; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3169203. eng.

Padwa H, Teruya C, Tran E, et al. The Implementation of Integrated Behavioral Health protocols in primary care settings in Project Care. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;62:74–83. PubMed PMID: 26683125; eng.

Park TW, Cheng DM, Samet JH, et al. Chronic care management for substance dependence in primary care among patients with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):72–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300414. PubMed PMID: 25219686; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4282827. eng.

Urada D, Schaper E, Alvarez L et al. Perceptions of mental health and substance use disorder services integration among the workforce in primary care settings. J Psychoact Drugs 2012 Sep-Oct;44(4):292–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2012.720163. PubMed PMID: 23210377; eng.

Kalapatapu RK, Ho J, Cai X et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in depressed primary care patients with co-occurring problematic alcohol use: effect of telephone-administered vs. face-to-face treatment-a secondary analysis. J Psychoact Drugs 2014;46(2):85–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2013.876521. PubMed PMID: 25052784; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4110640. eng.

Marshall KL, Deane FP. General practitioners’ detection and management of patients with a dual diagnosis: Implications for education and training. 2004;23(4):455–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230412331324572.

Sandvik H, Hetlevik Ø, Blinkenberg J, et al. Continuity in general practice as predictor of mortality, acute hospitalisation, and use of out-of-hours care: a registry-based observational study in Norway. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(715):e84–90. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp.2021.0340. PubMed PMID: 34607797; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8510690. eng.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

The study is supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation research grant (NNF16OC0022038). This funding body had no role in the design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor the writing of the manuscript.

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT: Planned study, reviewed articles, performed summary analysis, and drafted and revised manuscript. BC: Planned study, reviewed articles, performed summary analysis, and drafted manuscript. MHN: Planned study, reviewed articles, and revised manuscript. CH: performed revision and supervision on analysis and manuscript. AM: Planned study, reviewed articles, performed summary analysis, and drafted and revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

N/A.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tranberg, K., Colnadar, B., Nielsen, M.H. et al. Interventions targeting patients with co-occuring severe mental illness and substance use (dual diagnosis) in general practice settings – a scoping review of the literature. BMC Prim. Care 25, 281 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02504-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02504-3