Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular diseases are often accompanied by comorbidities, which require good coordination of care. Especially in fragmented healthcare systems, it is important to apply strategies such as case management to achieve high continuity of care. The aim of this study was to document continuity of care from the patients’ perspective in ambulatory cardiovascular care in Germany and to explore the associations with patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study was performed in primary care practices in Germany. The study included patients with three recorded chronic diseases, including coronary heart disease. Continuity of care was measured with the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire, which addresses personal/relational and team/cross-boundary continuity. From aspects of medical care and health-related lifestyle counselling a patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention index was formed with a range of 0–7. The association between continuity of care within the family practice and patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention was examined, using a linear multilevel regression model that adjusted for sociodemographics, structured care programme and numbers of contacts with the family practice.

Results

Four hundred thirty-five patients from 26 family practices participated. In a comparison between general practitioners (GPs) and cardiologists, higher values for relational continuity of care were given for GPs. Team/cross-boundary continuity for ‘within the family practice’ had a mean of 4.0 (standard deviation 0.7) and continuity between GPs and cardiologists a mean of 3.8 (standard deviation 0.7). Higher personal continuity of care for GPs was positively associated with patient-reported experience (b = 0.75, 95% CI 0.45–1.05, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Overall, there was high patient-reported continuity, which positively influenced the experience of cardiovascular prevention. Nevertheless, there is potential for improvement of personal continuity of the cardiologists and team/cross-boundary continuity between GPs and cardiologists. Structured care programs may be able to support this.

Trial registration

We registered the study prospectively on 7 November 2019 at the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) under ID no. DRKS00019219.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular diseases are the most common cause of death worldwide and are often accompanied by comorbidities, which requires good coordination of care [1, 2]. The aim of care coordination is to achieve high continuity of care, because this is associated with lower rates of hospitalisation and mortality [3, 4]. A high continuity of care also enhances patients’ feeling of security and confidence [5, 6]. According to Haggerty et al. [7], continuity of care has three dimensions: informational continuity (information sharing between different providers of information on medical history and patient preferences), relational continuity (having a trusting relationship with a healthcare provider), and management continuity (if multiple providers are involved in care, their approach is consistent with one another and congruent with patient needs). Therefore, especially in fragmented systems, such as in Germany, it is important to apply strategies such as case management, to achieve high continuity of care. It is crucial to elicit the patient’s perspective on perceived healthcare as only patients experience the full trajectory of their care episodes.

Ambulatory care in Germany, which includes primary care and specialised outpatient services, is primarily organized in single-handed practices with one to two physicians and around one to four practice assistants [8]. In 2009, general practitioner (GP)-centred care (German: “Hausarztzentrierte Versorgung”) was introduced to enforce strong general practice care and counteract fragmentation, which is specified in paragraph 73b of the German Social Code Book Five. The GP-centred care includes, for example, participation in structured care programmes for chronic conditions and referrals to specialists being exclusively coordinated by the general practitioner. Participation in these primary care programmes is optional for the patient and is offered by the statutory health insurance companies. Alternatively, patients may choose to remain in standard care, where there is a free choice of specialist without prior consultation or referral from the GP. In the structured care programmes (disease management programmes), the care for chronically ill people such as those suffering from chronic heart disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus is regulated. These programmes, e. g., include a quarterly consultation with the GP to check the state of health and progression of the respective condition, through, for example, blood pressure measurements and weight checks [9].

Following Haggerty et al. [7], Uijen et al. [10, 11] distinguish two domains in continuity of care from the patient's perspective: a) personal/relational and b) team/cross-boundary continuity. They found that patients had difficulty distinguishing between informational and management continuity, so they combined these domains as team/cross-boundary continuity.

In their study using health insurance claims data with a mixed study population from Germany, Wensing et al. [12] showed that, overall, there was a high personal continuity of care with respect to the Usual Care Provider Index (concentration of contact with a specific healthcare provider within an episode of care). In addition, participation in primary care-centred care resulted in lower hospitalisation. Vogt et al. [13] reached similar conclusions for heart failure with German claims data from 2010. With a maximum continuity of 1, they found a mean range of 0.77 to 0.89. The continuity of care indices were associated with lower hospitalisation, as was shown in logistic regression.

In addition to mortality, hospitalisation and other health outcomes, the provision of preventive medication and lifestyle counselling are important indicators of high-quality care. For example, care guidelines recommend nutrition or activity counselling [14]. For instance, the prescription of statins is mentioned as a quality indicator of good healthcare in patients with coronary heart disease [15, 16]. Studies by Ludt et al. [17] found that the documented lifestyle counselling showed that there is potential for improvement. These previous studies did not consider the role of ambulatory cardiologists, who provide cardiovascular prevention and treatment in Germany and thus need to be considered in research on care continuity and outcomes of cardiovascular care.

The aims of this study were to document patients’ perceptions of continuity of care, their experience of cardiovascular prevention in German primary and ambulatory care settings and to explore the associations between continuity of care and experience of cardiovascular care.

Methods

Study design and study population

This cross-sectional observational study was part of the ExKoCare project, which examined information-exchange networks in German primary care [18]. The three-year (2019–2022) project aimed to recruit a sample of 40 family practices to explore coordination and continuity of cardiovascular care in the German states of Baden-Wuerttemberg (approximately 11 million inhabitants, sampling in 10 of the 44 counties), Rhineland-Palatinate (approximately 4 million inhabitants, sampling in 13 of the 36 counties), and Saarland (approximately 1 million inhabitants, sampling in 2 of the 6 counties). The study received ethics approval from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg (ID: S-726/2018) and from the respective State Medical Chambers. Due to the survey being anonymous, Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg approved waiver for informed consent. Additionally, participants were informed about this in writing, as well as that returning the questionnaire is sufficient. We registered the study prospectively on 07/11/2019 at the German Clinical Trials Register under ID no. DRKS00019219. The reporting guideline ‘STROBE’ [19] for observational studies was considered in the reporting of this study (see Supplementary file 1).

The study population comprised patients with at least three recorded chronic diseases, one of them being coronary heart disease (ICD-10-GM-2022 I25.), who were registered with the participating primary care practices. We set three chronic conditions as inclusion criteria to achieve some complexity and need for care coordination.

Data collection

Data on sociodemographics, cardiovascular care and continuity of care were collected using a written anonymised questionnaire with validated and newly developed parts. The questionnaire used a pseudonym for each practice, so that the results could be assigned accordingly. After the practice owners consented to the ExKoCare study, all practices were contacted and invited to support patient recruitment. The aim was to recruit 15 patients from each primary care practice (n = 600 in total). We assumed a response rate of 30%, and so we intended to invite 50 patients per practice. The research team assisted the practices via phone in identifying potential study participants to ensure that the inclusion criteria were met. A list of potential participants was compiled from the physicians' billing systems. This system lists all patients from whom services have been billed, regardless of whether they regularly visit this doctor. Then, up to 50 patients were selected by selecting every 3rd patient from a starting point specified by the researcher. If there were fewer than 50 patients on the list, all were selected. Prior to this, the physician was asked to check for the cognitive ability to complete a questionnaire and potential contra-indications. Patients were sent the questionnaire by post and an anonymous return envelope addressed to the research department was included, so that the practices did not know which patients participated.

Measures

The questionnaire included four parts. The first part asked for personal and medical history data such as sex (male or female), age in years, health insurance (statutory health insurance, private health insurance, self-pay patient and other), chronic conditions (e.g. coronary heart disease, chronic heart failure or diabetes mellitus type 2) and participation in structured care programme (disease management programme or GP-centered care).

The second part was the validated Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire (NCQ) [10, 11]. The NCQ was developed in The Netherlands and validated in different countries and applied in different settings (e.g., in Norway in the field of rehabilitation) [10, 20]. The 12-item NCQ includes the following subscales: personal continuity-1 (‘care provider knows me’, items 1–5), personal continuity-2 (‘care provider shows commitment’, items 6–8), and team/cross-boundary continuity (items 9–12). The two subscales for personal continuity were used to assess the continuity regarding the family doctor and cardiologist and the team continuity for family practice (continuity between physicians and practice assistants) and the cross-boundary continuity between family doctor and cardiologist. Thus, the questionnaire contained six continuity of care scores and a total of 24 items.

Each question could be answered on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neutral), 4 (agree) to 5 (strongly agree), or with I do not know. The English version of all 12 items in the NCQ was translated carefully and independently by CA and PH using a forward translation into German and a backwards translation into English. After the independent translations, consensus discussions were held and a common German version was produced. A test with interviews in 6 patients did not identify significant lack of clarity.

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to examine the postulated clustering of items for the general practice and cardiologist domains. The analysis for general practitioners had a comparative fit index of 0.95, a root mean square error of approximation of 0.10, and a standardised root mean square residual of 0.04. The analysis for cardiologists showed a comparative fit index of 0.92, a root mean square error of approximation of 0.13, and a standardised root mean square residual of 0.05. The comparative fit index for both healthcare providers confirmed a good fit.

The last two sections of the self-administered questionnaire referred to cardiovascular care. Patient-reported numbers of cardiovascular contacts in the last three months with different healthcare professionals (e. g. general practitioners, cardiologists and nurses). The patients were also asked whether they had been treated regularly by one or more GP.

Questions on patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention during the past 12 months were derived from the two National Health Care Guidelines for chronic coronary heart disease and heart failure and from quality indicators of ambulatory care in Germany [14, 15, 21]. Content validity was assured by careful deduction of indicators from key aspects of prevailing clinical guidelines on cardiovascular prevention. In addition, an analysis of missing values was performed to provide a measure of the comprehensibility of the questionnaire. From aspects of medical care and health-related lifestyle counselling in the past 12 months (advice on physical exercise, advice on weight, advice on eating habits, discussion of therapeutic goals and medication plan, handing out of informational material about heart disease and the prescription of statins) a patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention index was formed with a range of 0–7. All of the seven items were weighted equally. The maximum value of 7 indicates that the patient has received all lifestyle counselling and medical care in the past 12 months. More items answered with ‘yes’ were interpreted as better experience of cardiovascular prevention.

Data analysis

The paper-based questionnaires were scanned and imported into a computer file. All analyses were performed in R (version 4.0.5) using R Studio (version 1.2.5033).

First, patient characteristics, contacts with various healthcare providers and items of patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention were analysed. The descriptive analysis included frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables according to distribution. Categorical variables were tested for independence with regard to inclusion in the final regression analysis using Chi2-tests. For the metric variables, a t-test was performed accordingly.

To calculate the scores of ‘continuity of care’, cases were excluded if more than one item within each scale was missing and afterwards the mean with SD per subscale was computed. We did not perform imputation because of the possibility that a missing value meant no contact with a physician, which meant no assessment was possible. The difference between the personal continuity of care of the GP and the cardiologist was calculated using the t-test for independent samples. The independent samples t-test was also used to compare the subscale team/cross-boundary continuity within the GP practice (between the GP and the practice assistant) and outside the GP practice (between GP and cardiologist).

Relationships between patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention and the reported continuity of care were explored using the Pearson product-moment correlation. A correlation coefficient between 0.3 and 0.5 was considered as moderate and > 0.5 as a strong correlation [22].

Finally, due to the hierarchical structure of the data, we performed a linear multilevel analysis with the dependent variable ‘patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention score’ and the independent variable continuity of care. The final model was adjusted at level 1 for age, sex, numbers of chronic conditions, participation in disease management-programme and for numbers of contacts to GP. The second level was made up of the GP practices. In the first step of the final multilevel analysis, we calculated the null model without predictors and derived the intra-class correlation from it. In the second model, the predictors were inserted as fixed effects, thus creating a random intercept model. Restricted maximum likelihood was used to estimate the parameters.

The final model, which is presented in the results section, was selected on the basis of multicollinearity, model fit, content-related aspects, and the number of cases. We assumed multicollinearity if the correlation coefficient was greater than 0.6. The goodness of fit of the regression models was measured using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). To decide on the final model based on these characteristics, various regression analyses were performed. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

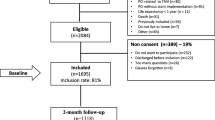

Data were collected from November 2020 to December 2021. As planned, 42 primary care practices were recruited. However, 16 practices did not agree to patient recruitment, which seemed related to the workload that was induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient identification was difficult due to the partly incomplete coding of the diseases. It was not possible to identify 50 patients in all practices. The 26 participating practices sent 811 questionnaires to patients (n = 31 on average). Due to missing values Sat the predictors, only 247 cases could be included in the final regression model.

A total of 435 patient questionnaires from 26 family practices were returned, giving a response rate of 53.6% and on average 16.7 responding patients (1 to 33 patients) per practice. Table 1 shows key patient characteristics. Of the 435 participants, 316 (73.0%) were male and the mean age was 74.7 (SD 9.0) years. Furthermore, only 56.1% of the patients reported chronic coronary heart disease, although this disease was recorded for all patients by physicians. Patients reported a mean of 2.0 (SD 1.0, range 0–7) heart diseases and 1.7 (SD 1.5, range 0–9) co-morbidities. Ninety-four participants did not indicate comorbidities.

In terms of care, 384 (90.8%) patients reported one usual GP, while 39 (9.2%) being seen by two GPs on a regular basis. Table 2 presents information about the patients’ contact with different healthcare providers. Patients reported having the most contact with pharmacists (median 2 IQR 1–3), followed by GPs and practice assistants in family practices (median 1 IQR 0–2).

Table 3 summarises patient-reported continuity of care. In a comparison between GPs and cardiologists, higher values for relational continuity of care were given for GPs. A higher degree of team/cross-boundary continuity was reported within the GP practice compared to outside the GP practice. Across all items, there were 18.5% missing values or the patients could not make a response. 190 people completed the NCQ in full. Data regarding the continuity of care of the subsample of the final regression analysis can be found in the appendix (see Supplementary file 2). There was no statistically significant difference to the overall sample.

Table 4 provides an overview of patient-reported healthcare experience of cardiovascular prevention during the past 12 months. The body weight check was the care item most often recorded by patients (247 (58.0%)). In contrast only 90 (21.6%) stated that they had discussed their therapy goals and 24 (5.6%) that they had discussed their medication plan with their GP. Comparison between the final sample of the regression analysis and the excluded cases showed that the variables ‘advice on exercises’ and ‘talk about eating habits’ differed statistically significant between both groups. Patients from the final analysis-sample had answered ‘yes’ to the items more often.

Patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention score (range 0–7) had a mean of 3.5 (SD 1.7) in the study population. Pearson correlation between healthcare score and continuity of care within the GP practice was r = 0.29, P < 0.001 and between healthcare score and personal continuity (‘GP shows commitment’) r = 0.37, P < 0.001. Table 5 presents the results of final multilevel regression analyses for patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention score: adjusted for all other variables sex, age and numbers of contacts with GP were not statistical significantly associated with the experience of cardiovascular prevention score. Due to multicollinearity, we were able to include only 3 of the 6 continuity of care scales in the final regression model (see Supplementary file 3). In the personal continuity domain, we chose the second subscale of the GPs, because GPs are primarily involved in the preventive care interventions and the model with the second subscale (“care provider shows commitment”) had a better model fit compared to the model with the first subscale (“care provider knows me”). The two team/cross-boundary continuity were selected, because they represent the coordination of different healthcare provides. Higher personal continuity of care for the GP was positively associated with the healthcare experience of cardiovascular prevention score (b = 0.75, 95% CI 0.45–1.05, P < 0.001). The goodness of fit of the final model with an AIC of 942 was better than the null model with 1,700. The interclass correlation was 0.08.

Discussion

This study found that patients perceived high personal and team/cross-boundary continuity of general practice care, which was somewhat higher than the continuity of ambulatory cardiology care. Higher personal continuity was associated with higher patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention, independent of patients’ number of contacts in primary care. The study adds to the accumulating evidence on the benefits of high continuity of primary care [23,24,25].

Our findings are in line with a previous study with administrative data, which reported a high continuity of care in Germany in comparison with other countries e. g. United Kingdom [12]. This underlines that GPs have a core function in the care of patients with cardiovascular diseases and, combined with the relatively high number of contacts in German primary care, allows patients and physicians to know each other well. Since 2009, GP-centered care exists in Germany [8, 9], which assigns a pilot function to GPs. For example, as a result of GP-centered care, referrals to medical specialist are managed by GPs, so they always know the patients’ conditions and uncontrolled visits to specialists are avoided. In the present study, a little more than half of the participants stated that they took part in this programme.

The personal continuity of care was rated higher for GPs than for cardiologists, which was expected due to the primary care physician's role as the primary point of contact for patients. These results are consistent with studies from other countries and specialties. In the study of Cohen Castel et al. 2018 [26], patients reported a mean of 3.8 (SD 1.0) for personal continuity (‘care provider knows me’) for GPs and compared to 3.5 (1.0) for oncologists. In Uijen et al. 2012 [10], patients reported a mean of 3.7 for GPs and for various specialists 3.6. The population included patients with various chronic diseases.

The questions regarding cardiologists were answered by significantly fewer people compared to the questions concerning the GP. In addition, 56.6% reported no contact with a cardiologist during the last three months. Presumably, for these patients (recruited in general practices) contacts with cardiologists were too infrequent to answer the questions. Here, the survey of the annual contact would have been interesting, as this is also recommended in the guidelines [14, 21, 27]. Due to the phrasing of our questionnaire, we could not differentiate between whether the guideline recommendations for the involvement of cardiologists were not adhered to, or whether there was simply no contact in the past three months, but still a contact in the past year as recommended by the guidelines.

As already published in earlier studies by Ludt et al. [17, 28], the lifestyle counselling and patient-reported experience of care showed that there is potential for improvement. In our study, about half of the patients received lifestyle counselling in the past 12 months. Especially in the area of the patient's participation in their disease and therapy, there is still great potential. Therapy goals and medication schedules were only discussed between GPs and patients in less than a quarter of cases. The lack of information can also be seen in the results on heart diseases: only slightly more than half of the patients stated a coronary heart disease, while all of them were diagnosed with it by their physician according to the ICD codes (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) that were used for recruitment. In contrast, good conversion to statin therapy was seen in 81% of patients, which is close to the 85% considered as a quality indicator and to other study findings [15, 29]. Although many patients take statins, they do not seem to be informed that they have a coronary heart disease.

Our study showed a positive influence of comorbidities on experience of care. It is possible that sicker patients in particular are receiving more preventive care due to their higher physician contacts. In contrast, there is a greater need for coordination in the presence of comorbidities [30]. The study demonstrated the positive association between coordinated care as measured by personal continuity for GPs as well as participation in a structured care programme and patient-reported experience of care. This is consistent with other studies [31, 32]. Explanatory mechanisms may be that by establishing a doctor-patient relationship, trust is strengthened and the doctor's sense of responsibility increases, and appropriate preventive measures are taken to delay the progression of coronary heart disease [33]. Several trends in healthcare may reduce personal continuity, for instance ongoing medical specialization and increasing emphasis on work-life balance of physicians. Continuity of care may also be achieved in teams and networks of healthcare providers, but it needs careful design to make sure that its effects on healthcare performance and health outcomes are not lost.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study was the high response rate of 53.6%. The number of missing items of the NCQ was moderate with 18.5%. However, the effective sample size in the regression analysis was reduced by missing values, especially in the questions on cardiologists. The comparison between the final sample of the regression analysis and the excluded cases showed that there is a potential selection bias with regard to patient-reported cardiovascular prevention, which must be considered in the interpretation of the results. It cannot be excluded that the positive correlation between continuity of care and cardiovascular prevention resulted from this bias. Another limitation is the extended recruitment time due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, this makes the interpretation of the results difficult, as it is unclear whether there were fewer contacts with the providers due to the pandemic and whether this was only a snapshot or also existed before and after the pandemic. Unfortunately, we failed to ask if the treatment was with different GPs within one practice or different ones. This would have been additional information to assess continuity of care, as there is presumably a higher exchange of information within one practice. During recruitment, some physicians noticed that their ICD codes were not consistently documented – this possibly led to a selection bias. In addition, we cannot make any explicit statements about the number of patients with coronary heart diseases in the participating practices. Around 2,000 patients with coronary heart diseases could be identified from 24 practices of which around 800 were invited to the study. Two practices could not provide any information on this. Furthermore, there is the opportunity of social desirability bias, as it can be assumed that patients want to rate their physicians positively. In addition, only 7.2% (n = 30) reported positive smoking status, which could also indicate social desirability bias. It would also have been interesting to perform a subgroup analysis for smokers to determine the experience of care they receive, since smoking status can be seen as a predictor of coronary heart disease. However, this was not possible due to the number of cases. For a better interpretation of the results, it would have been helpful to monitor the duration and severity of the heart disease. Not all parts of the questionnaire were validated, however, aspects were derived from guidelines and already used in previous larger projects, for example in the EPA-project [34].

Conclusions

In this study, a high continuity of care could be shown especially regarding GPs, which was associated with higher patient-reported experience of cardiovascular prevention. Structured care programs could possibly help to increase continuity in the area of team/cross-boundary continuity and thus improve the experience of care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This is due to ongoing research and our promise to the participants to only share aggregated data in terms of manuscripts and conference presentations.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DMP:

-

Disease management programme

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- ICD:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NCQ:

-

Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire

- Ref:

-

Reference group

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(42):3232–45.

Buddeke J, Bots ML, van Dis I, Visseren FL, Hollander M, Schellevis FG, et al. Comorbidity in patients with cardiovascular disease in primary care: a cohort study with routine healthcare data. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(683):e398–406.

Baker R, Freeman GK, Haggerty JL, Bankart MJ, Nockels KH. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e600–11.

Facchinetti G, D’Angelo D, Piredda M, Petitti T, Matarese M, Oliveti A, et al. Continuity of care interventions for preventing hospital readmission of older people with chronic diseases: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;101:103396.

Haggerty JL, Roberge D, Freeman GK, Beaulieu C. Experienced continuity of care when patients see multiple clinicians: a qualitative metasummary. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):262–71.

Wilfling D, Warkentin N, Laag S, Goetz K. “i have such a great care” – geriatric patients’ experiences with a new healthcare model: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:309–15.

Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–21.

Busse R, Blümel M, Knieps F, Bärnighausen T. Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. The Lancet. 2017;390(10097):882–97.

Bundesministerium der Justiz und Verbraucherschutz. Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V) - Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung - (Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477) § 73b Hausarztzentrierte Versorgung. 2021. Available from: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_5/__73b.html. Accessed 9 Feb 2022.

Uijen AA, Schellevis FG, van den Bosch WJ, Mokkink HG, Van Weel C, Schers HJ. Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire: development and testing of a questionnaire that measures continuity of care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1391–9.

Uijen AA, Schers HJ, Schellevis FG, Mokkink HG, Van Weel C, van den Bosch WJ. Measuring continuity of care: psychometric properties of the Nijmegen continuity questionnaire. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(600):e949–57.

Wensing M, Szecsenyi J, Laux G. Continuity in general practice and hospitalization patterns: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):21.

Vogt V, Koller D, Sundmacher L. Continuity of care in the ambulatory sector and hospital admissions among patients with heart failure in Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(4):555–61.

Bundesärztekammer, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie KHK Langfasssung 5. Auflage Version 1 2019 [11.09.2019]. Available from: https://www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/herzinsuffizienz/herzinsuffizienz-2aufl-vers3-lang.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2022.

Andres E, Bleek J, Stock J, Bader E, Gunter A, Wambach V, et al. Messen, Bewerten, Handeln: Qualitatsindikatoren zur Koronaren Herzkrankheit im Praxistest. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2018;137–138:9–19.

Jeitler K, Semlitsch T. Qualitätsindikatoren für die Versorgung von Patientinnen und Patienten mit koronare Herzkrankheit. In: Szecsenyi J, Broge B, Stock J, editors. QiSA-das Qualitätsindikatorensystem für die ambulante Versorgung. 2.0 ed. Berlin: KomPart-Verlags-Gesellschaft; 2019. ISBN: 978-3-940172-40-2.

Ludt S, Petek D, Laux G, Van Lieshout J, Campbell SM, Künzi B, et al. Recording of risk-factors and lifestyle counselling in patients at high risk for cardiovascular diseases in European primary care. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2012;19(2):258–66.

Arnold C, Hennrich P, Koetsenruijter J, van Lieshout J, Peters-Klimm F, Wensing M. Cooperation networks of ambulatory health care providers: exploration of mechanisms that influence coordination and uptake of recommended cardiovascular care (ExKoCare): a mixed-methods study protocol. BMC family practice. 2020;21(1):168.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):805–35.

Hetlevik O, Hustoft M, Uijen A, Assmus J, Gjesdal S. Patient perspectives on continuity of care: adaption and preliminary psychometric assessment of a Norwegian version of the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire (NCQ-N). BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):760.

Bundesärztekammer, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Chronische Herzinsuffizienz Langfassung 3. Auflage 2019 [10.03.2020]. Available from: https://www.leitlinien.de/mdb/downloads/nvl/herzinsuffizienz/herzinsuffizienz-3aufl-vers1-lang.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2022.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences: Academic press; 2013. ISBN:1848729812

Youens D, Doust J, Robinson S, Moorin R. Regularity and continuity of gp contacts and use of statins amongst people at risk of cardiovascular events. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1656–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06638-3.

Delgado J, Evans PH, Gray DP, Sidaway-Lee K, Allan L, Clare L, Ballard C, Masoli J, Valderas JM, Melzer D. Continuity of GP care for patients with dementia: impact on prescribing and the health of patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(715):e91–8. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2021.0413.

Pereira Gray DJ, Sidaway-Lee K, White E, Thorne A, Evans PH. Continuity of care with doctors-a matter of life and death? A systematic review of continuity of care and mortality. BMJ Open. 2018;8(6):e021161. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021161.

Cohen Castel O, Dagan E, Keinan-Boker L, Shadmi E. Reliability and validity of the Hebrew version of the Nijmegen continuity questionnaire for measuring patients’ perceived continuity of care in oral anticancer therapy. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(6):e12913.

Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, Benetos A, Biffi A, Boavida JM, Capodanno D, Cosyns B, Crawford C, Davos CH, Desormais IDI, Angelantonio E, Franco OH, Halvorsen S, Hobbs FDR, Hollander M, Jankowska EA, Michal M, Sacco S, Sattar N, Tokgozoglu L, Tonstad S, Tsioufis KP, van Dis I, van Gelder IC, WannerWilliams CB. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur Heart J. 2021;42(34):3227–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484.

Ludt S, Van Lieshout J, Campbell SM, Rochon J, Ose D, Freund T, et al. Identifying factors associated with experiences of coronary heart disease patients receiving structured chronic care and counselling in European primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):1–11.

Wagner M, Gelbrich G, Kircher J, Kotseva K, Wood D, Morbach C, et al. Secondary Prevention in Younger vs. Older Coronary Heart Disease Patients-Insights from the German Subset of the EUROASPIRE IV Survey. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(3):283–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9691-y.

van Oostrom SH, Picavet HS, de Bruin SR, Stirbu I, Korevaar JC, Schellevis FG, Baan CA. Multimorbidity of chronic diseases and health care utilization in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-61.

Hofer A, McDonald M. Continuity of care: why it matters and what we can do. Aust J Prim Health. 2019;25:214–8. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY19041.

Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract. 2004;53(12):974–80.

Sidaway-Lee K, Pereira Gray D, Harding A, Evans P. What mechanisms could link GP relational continuity to patient outcomes? Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(707):278–81.

Ludt S, Campbell SM, van Lieshout J, Grol R, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M. Development and pilot of an internationally standardized measure of cardiovascular risk management in European primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:70.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients for participating in our study, all GP practices for the support in the recruitment of the patients and our research assistant Pia Traulsen for her support of data entry and study administration.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work is funded by the ‘Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)’ under grant number 416396249. The funding body had no influence in the design of the study nor in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data as well as the writing of related manuscripts. The study protocol has been independently peer reviewed by the funding body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA conducted the data collection, the data analysis and wrote the first draft of manuscript. PH performed the confirmatory factor analysis and data collection. CA, PH and MW interpreted the results. All authors participated in the revision and approved the final manuscript. MW has supervised all steps of the study as principal investigator.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received a positive ethics vote from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg (ID: S-726/2018) and from The State Medical Chambers of Baden-Wuerttemberg (German: Landesärztekammer). The study was performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki in its latest version. Due to the survey being anonymous, Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg approved waiver for informed consent. Additionally, participants were informed about this in writing, as well as that returning the questionnaire is sufficient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Reporting guideline.

Additional file 2.

Continuity of Care.

Additional file 3.

Correlation matrix Continuity of Care (n = 247).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arnold, C., Hennrich, P. & Wensing, M. Patient-reported continuity of care and the association with patient experience of cardiovascular prevention: an observational study in Germany. BMC Prim. Care 23, 176 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01788-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01788-7