Abstract

Background

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) tailored to the context of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Adaptation of guidelines accounts for contextual factors and becomes more efficient than de novo guideline development when relevant, good quality, and up-to-date guidelines are available. The objective of this study is to describe the methodology used for the adolopment of the 2021 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines for the treatment of RA in the KSA.

Methods

We followed the ‘Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (GRADE)-ADOLOPMENT methodology. The adolopment KSA panel included relevant stakeholders and leading contributors to the original guidelines. We developed a list of five adaptation-relevant prioritization criteria that the panelists applied to the original recommendations. We updated the original evidence profiles with newly published studies identified by the panelists. We constructed Evidence to Decision (EtD) tables including contextual information from the KSA setting. We used the PanelVoice function of GRADEPro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) to obtain the panel’s judgments on the EtD criteria ahead of the panel meeting. Following the meeting, we used the PANELVIEW instrument to obtain the panel’s evaluation of the process.

Results

The KSA panel prioritized five recommendations, for which one evidence profile required updating. Out of five adoloped recommendations, two were modified in terms of direction, and one was modified in terms of certainty of the evidence. Criteria driving the modifications in direction were valuation of outcomes, balance of effects, cost, and acceptability. The mean score on the 7-point scale items of the PANELVIEW instrument had an average of 6.47 (SD = 0.18) across all items.

Conclusion

The GRADE-ADOLOPMENT methodology proved to be efficient. The panel assessed the process and outcome positively. Engagement of stakeholders proved to be important for the success of this project.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The development of new guidelines is time- and resource-intensive. Alternatively, guideline developers can adopt existing recommendations, or adapt them to their own context [1]. When relevant, good quality, and up-to-date guidelines are available, adoption and adaptation become more efficient than development of new guidelines [2]. Some recommendations are context sensitive, i.e., their strength and/or direction are likely to be affected by contextual factors such as resources needed and acceptability. For such recommendations, adaptation accounting for contextual factors would lead to better applicability and subsequent uptake compared to adoption.

The ‘Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (GRADE)-ADOLOPMENT approach is increasingly being used to build on existing guidelines [3]. Adolopment includes the identification and prioritization of existing guidelines, the evaluation and completion of GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) tables for each recommendation, and final adoption, adaptation, or de novo development of recommendations. This approach has been applied in the region for a number of guideline topics [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9].

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) tailored to the context of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Management follows recommendations of both the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [10, 11]. Yet, there are relevant differences in the KSA healthcare system and population that may affect certain recommendations. First, the KSA’s healthcare system consists of several sectors that report to different authorities and have their own resources, such as infusion units and medication formulary. Additionally, access to healthcare varies among different segments of the population, such as national civilians, military staff, and expatriates. While national civilians access the public healthcare system for free, expatriates can access only the private system through their insurance plans. The military staff has access to military hospitals. In addition, the availability of different types of medications varies by hospital [11].

Recently, the ACR published the 2021 update of guidelines for the treatment of RA [10]. The objective of this paper is to describe the methodology used for the adolopment of the 2021 ACR guidelines for the treatment of RA in the KSA [12].

Methods

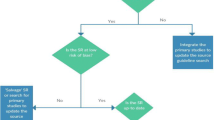

We followed the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT methodology [3]. This methodology builds on the GRADE EtD framework, in that it uses the EtD criteria that determine the direction and strength of a recommendation to allow for the development of context-specific recommendations. Hence, the completion of GRADE EtDs for each guideline recommendation is a central element of this approach [3]. We provide an overview of the methodology in Fig. 1. In the subsequent sections, we describe the source guideline, groups involved, the process for prioritization of recommendations and outcomes, sources of data, the adolopment process and its evaluation.

The source guideline

The 2021 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines for the treatment of RA includes 43 recommendations addressing questions on treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (24 recommendations), use of glucocorticoids (4 recommendations), and use of DMARDs in certain high-risk populations (15 recommendations). The development of the guidelines included the use of GRADE evidence tables and graded recommendations while accounting for the balance of benefits and harms, the certainty of the evidence, patient values and preferences, and resource use. While the methodology builds on the key principles of GRADE and includes many of the components of the GRADE EtD framework in a modified decision support voting mechanism, it does not explicitly include the production of an EtD table for each recommendation [13].

Groups involved

The project involved a coordination group and a guideline panel. The coordination group included the two content experts leading the project (MAO, HAR) and three methodologists (EAA, JK, and SY). That group facilitated the handling of both logistical and methodological aspects of the work. The panel included representatives from different stakeholder groups, including rheumatologists, a pharmacist, a patient representative, and policymakers. The rheumatologists included two international experts (the chair of the source guideline and the chair of the 2015 ACR guideline [4]). The panel included 19 members from the different Saudi regions and type of practice (i.e., both governmental and private). Table 1 presents the characteristic of panel members. There were multiple touchpoints between the coordination team and the panel through email communication and online meetings.

Prioritization of recommendations and outcomes

Given the limited time and resources, the coordination group chose to prioritize five recommendations to be adapted from the source guideline. First, we developed a list of five adaptation-relevant prioritization criteria (Table 2). The selection of these criteria was based on (1) two reviews of the literature on prioritization for guideline development [14, 15], (2) a review of handbooks by 23 guideline-producing organizations on guideline adaptation (unpublished), and (3) expert input from the rheumatologist members of the coordination group. Second, through an online survey, we asked panelists to rate the priority of each of the source recommendations based on each criterion on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 indicating lowest priority, and 5 indicating highest priority). Third, we produced a list of ranked recommendations using the average priority score for each recommendation. The latter consisted of the average priority score across the five criteria for prioritization and across all respondents. Finally, we selected for the adaptation effort the five recommendations with the highest priority scores.

As for the prioritization of outcomes, we reviewed the priority list set by the ACR and the systematic review on the topic [16], i.e., disease activity as a critical outcome; and physical function, radiographic progression, quality of life, and adverse events as important outcomes. The panel adopted these outcomes and their valuation after a discussion including the patient representative.

Sources of data

Figure 2 presents the sources of data for the adolopment effort. Specifically:

-

Evidence on health effects: we judged that a formal update of the evidence reports published by the ACR guidelines was not needed given the short timeframe between the publication of the source guideline and the adaptation project. Instead, we asked panelists to suggest any new studies published since the source guideline. If that was the case, we followed standard systematic review methodology to assess eligibility, abstract data and update the analyses, as described by the Cochrane handbook (e.g., duplicate and independent screening and data abstraction) [17]. Then, the three methodologists updated the GRADE evidence tables from the source guideline.

-

Values and preferences: as mentioned above, the panel adopted the source guideline's ratings after consideration of the relevant systematic review on the topic [16] and the input of the patient representative.

-

Cost data: we collected relevant cost data using two sources: the Saudi Food Drug Authority (SFDA) for the private sector [18] and the National Unified Procurement Company (NUPCO) for the governmental sector [19].

-

Other contextual factors (i.e., impact on equity, acceptability, feasibility): as we did not conduct a formal assessment of these factors, we relied on the panel’s personal knowledge and experience.

Adolopment process

The methodologists created EtD tables using the sources of data mentioned above. Before each recommendation meeting, we electronically shared the EtDs with the panelists and obtained their preliminary feedback and judgments using the PanelVoice function of GRADEPro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) (https://www.gradepro.org/). During the online panel meetings, the panelists decided on a judgment for each criterion of the EtD after reviewing the preliminary feedback and judgments, and discussion. When consensus could not be reached, we went with the majority vote and noted the vote results in the EtD.

Evaluation

After completing the panel meetings, we invited the panelists to complete an online survey to evaluate the adaptation effort. We used the PANELVIEW instrument, which consists of 34 items relating to the guideline process, methods and outcomes [20]. The PANELVIEW instrument covers, among others, administration, training, conflict of interest, group composition, group interaction, considering the evidence and contributing through expertise, and formulating the recommendations. Panelists were asked to indicate their agreement on each item using a 7-point Likert scale. We generated a mean score and its standard deviation (SD) for each item. We also generated a mean score and its standard deviation across items.

Results

We conducted the adolopment process over a period of four months. Additional file 1 shows the detailed timeline.

Adoloped recommendations

Table 3 presents the five adoloped recommendations, along with EtD criteria influencing any modification from the source recommendations. Out of five adoloped recommendations, two remained unmodified (#2 and #4). To note that for recommendation #2, the KSA panel considered the increased risk of hemolysis with the use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in the KSA due to the relatively high prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency in this population [21]. However, it did not lead to a modification in recommendation #2, as the panel still had higher safety concerns for sulfasalazine (SSZ).

For recommendation #1, the panel modified the direction in relation to the balance of effects, cost, and acceptability in relation to dosing convenience. Specifically, the KSA panel judged that the undesirable effects of methotrexate (MTX) were less relevant to the KSA setting (particularly in terms of alcohol-induced hepatoxicity). This tilted the balance of desirable and undesirable effects in favor of MTX. Also, the panel took into consideration that the cost of a 12-week treatment course of SSZ is substantially higher than that of MTX. In addition, the panel judged that a generally low rate of adherence to medications in the KSA favored MTX (administered weekly) over SSZ (administered twice daily) (acceptability criterion).

For recommendation #3, the panel modified the direction in relation to the valuation of outcomes and the balance of effects. Specifically, the KSA panel highly valued rapid alleviation of symptoms at the time of diagnosis and during flares. Accordingly, the KSA panel judged that the balance of effects “probably favors” short-term (< 3 months) glucocorticoids when initiating a csDMARD. Still, the KSA panel acknowledged a few challenges with glucocorticoid treatment and detailed them in the rationale as a note of caution to users.

For recommendation #5, we updated the evidence to incorporate a newly published study. As a result, the certainty of evidence increased from very low to moderate, but did not lead to a modification in the strength or direction of the recommendation.

Evaluation results

Out of 19 panelists, 13 filled the PANELVIEW survey. Additional file 2 presents the survey data, and Additional file 3 presents the mean and its standard deviation for each of the 34 evaluation questions. The mean scores on the 7-point scale ranged from 6.08 (for the items ‘adequate time was allotted for the final panel meeting for all guideline questions to be discussed and recommendations to be formulated’ and ‘the panel was given sufficient opportunity to be involved in the prioritization of questions and scoping of the guideline’) to 6.85 (for the item ‘I would participate in this guideline development process again’). There was a high ‘overall satisfaction’ with the guideline development process (mean score = 6.46). The mean score had an average of 6.47 (SD = 0.18) across all items.

Discussion

In this paper, we described the methodology used for the adolopment of the 2021 ACR guidelines for the treatment of RA in the KSA. The process followed the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT methodology, and involved prioritization of recommendations and outcomes, and construction of EtDs for each prioritized recommendation. We populated the EtDs with data from the source guideline and with contextual data from the KSA.

We engaged relevant stakeholder groups as panel members and they contributed to the different steps of the process, including prioritization of recommendations and outcomes, evidence gathering, and adolopment of recommendations. Representation from the different Saudi regions and type of practice (governmental and private) enriched the discussions and contributed to enhancing the applicability of the recommendations. In addition, the inclusion of two international experts from the source guideline provided the rest of the panel with unique insight into the context of the source guideline and the source panel’s judgments.

The use of the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT methodology allowed the contextualization of guidelines in a relatively short period of time. A major facilitator was the use of the same methodology (i.e., GRADE) and tools (i.e., GRADEPro GDT) used in the source guideline. In addition, the use of the EtD framework facilitated structured discussions, and ensured that the panel considered both evidence on health effects and contextual data. While we collected primary cost data from the KSA context, we did not do so for the remaining contextual factors and had to rely on expert evidence provided by the panelists. This could have been achieved through either quantitative surveys [22, 23] or mixed methods studies [24].

In this project, none of the five adoloped recommendations were modified from the source recommendations in terms of strength. Two out of the five adoloped recommendations were modified in terms of direction. In a previous adolopment effort of the 2015 ACR treatment guideline for RA, five out eight adoloped recommendations were modified, specifically in terms of their strengths [2, 4].

The factors driving modification in this project were balance of effects (n = 2), valuation of outcomes (n = 1), cost (n = 1), and acceptability (n = 1). These factors, in addition to impact on health equity, were also driving factors for modification of recommendations in two other guideline adolopment efforts in the region [2, 5].

The evaluation scores on the PANELVIEW instrument were high when compared with scores for eight other panels [20]. When comparing the scores that our panel gave to the different items, they were the highest (6.85 to 6.62) for items under the domains of administration, methodology and process, group interaction and overall satisfaction. The lowest scores (6.08) were given to the item addressing the adequacy of time allocated to the panel meeting, and to the item addressing the opportunity to be involved in the prioritization of questions and scoping of the guideline.

With the increasing move towards living guidelines, groups adapting recommendations must deal with the challenge of frequently updated recommendations [25, 26]. The methodology addressing this situation has not yet been discussed or explored. Furthermore, while the list of adaptation-relevant prioritization criteria that we developed has face validity, more work is needed to refine and validate it. Finally, there is a need to develop methods for efficient collection of primary contextual data that would allow their consideration in adaptation projects with very short timelines.

Conclusion

The GRADE-ADOLOPMENT methodology proved to be efficient. The panel positively assessed the process and outcome of this adolopment effort. The engagement of stakeholders with wide representation in terms of groups, regions and type of practice proved to be important for the success of this project.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- bDMARD:

-

Biologic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug

- csDMARD:

-

Conventional synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug

- EtD:

-

Evidence to Decision

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- G6PD:

-

Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- HCQ:

-

Hydroxychloroquine

- KSA:

-

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid Arthritis

- SSR:

-

Saudi Society for Rheumatology

- SSZ:

-

Sulfasalazine

- tsDMARD:

-

Targeted synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs

References

Darzi A, Abou-Jaoude EA, Agarwal A, Lakis C, Wiercioch W, Santesso N, et al. A methodological survey identified eight proposed frameworks for the adaptation of health related guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;86:3–10.

Darzi A, Harfouche M, Arayssi T, Alemadi S, Alnaqbi KA, Badsha H, et al. Adaptation of the 2015 American College of Rheumatology treatment guideline for rheumatoid arthritis for the Eastern Mediterranean Region: an exemplar of the GRADE Adolopment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):1–13.

Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Mustafa RA, Manja V, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:101–10.

Arayssi T, Harfouche M, Darzi A, Al Emadi S, A Alnaqbi K, Badsha H, et al. Recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis in the Eastern Mediterranean region: an adolopment of the 2015 American College of Rheumatology guidelines. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(11):2947–59.

Kahale LA, Ouertatani H, Brahem AB, Grati H, Hamouda MB, Saz-Parkinson Z, et al. Contextual differences considered in the Tunisian ADOLOPMENT of the European guidelines on breast cancer screening. Health Res Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):1–9.

Al-Hameed F, Al-Dorzi HM, Al Momen A, Algahtani F, Al Zahrani H, Al Saleh K, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: the Saudi clinical practice guideline. Ann Saudi Med. 2015;35(2):95–106.

Al-Hameed FM, Al-Dorzi HM, Abdelaal MA, Alaklabi A, Bakhsh E, Alomi YA, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in long-distance travelers. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(1):101.

Al-Hameed FM, Al-Dorzi HM, Abdelaal MA, Alaklabi A, Bakhsh E, Alomi YA, et al. The Saudi clinical practice guideline for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in medical and critically ill patients. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(11):1279.

Al-Hameed FM, Al-Dorzi HM, Al-Momen AM, Algahtani FH, Al-Zahrani HA, Al-Saleh KA, et al. The Saudi Clinical Practice Guideline for the treatment of venous thromboembolism: outpatient versus inpatient management. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(8):1004.

Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, St. Clair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, et al. American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;2021(73):1108–23.

Omair MA, Omair MA, Halabi H. Survey on management strategies of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia: a Saudi Society for Rheumatology Initiative. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(9):1185–92.

Omair MA, Al Rayes H, Khabsa J, Yaacoub S, Abdulaziz S, Al Janobi GA, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Saudi Arabia: adolopment of the 2021 American College of Rheumatology guidelines. BMC rheumatology. 2022;6(1):70.

American College of Rheumatology. Policy and Procedure Manual for Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2015.

El-Harakeh A, Lotfi T, Ahmad A, Morsi RZ, Fadlallah R, Bou-Karroum L, et al. The implementation of prioritization exercises in the development and update of health practice guidelines: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0229249.

El-Harakeh A, Morsi RZ, Fadlallah R, Bou-Karroum L, Lotfi T, Akl EA. Prioritization approaches in the development of health practice guidelines: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–10.

Durand C, Eldoma M, Marshall DA, Bansback N, Hazlewood GS. Patient preferences for disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(2):176–87.

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022): Cochrane; 2022. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

SFDA. Available from: https://www.sfdagovsa/en.

NUPCO. Available from: https://www.nupcocom/NupcoJobPortal/.

Wiercioch W, Akl EA, Santesso N, Zhang Y, Morgan RL, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, et al. Assessing the process and outcome of the development of practice guidelines and recommendations: PANELVIEW instrument development. CMAJ. 2020;192(40):E1138–45.

Hamali HA. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency: An Overview of the Prevalence and Genetic Variants in Saudi Arabia. Hemoglobin. 2021;45(5):287–95.

Ajuebor O, Cometto G, Boniol M, Akl EA. Stakeholders’ perceptions of policy options to support the integration of community health workers in health systems. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):1–13.

Darzi AJ, Officer A, Abualghaib O, Akl EA. Stakeholders’ perceptions of rehabilitation services for individuals living with disability: a survey study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):1–8.

Khabsa J, Jain S, El-Harakeh A, Rizkallah C, Pandey DK, Manaye N, Honein-AbouHaidar G, Halleux C, Dagne DA, Akl EA. Stakeholders’ views and perspectives on treatments of visceral leishmaniasis and their outcomes in HIV-coinfected patients in East Africa and South-East Asia: A mixed methods study. PLOS Neglected Trop Dis. 2022;16(8):e0010624.

Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, Kahale LA, Schünemann HJ, Agoritsas T, et al. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:47–53.

El Mikati IK, Khabsa J, Harb T, Khamis M, Agarwal A, Pardo-Hernandez H, Farran S, Khamis AM, El Zein O, El-Khoury R, Schünemann HJ. A framework for the development of living practice guidelines in health care. Annals Int Med. 2022;175(8):1154–60.

Acknowledgements

For the KSA 2021 ACR RA adolopment working group (author contributors)

Sultana Abdulaziz

MBBS, ABIM, JBIM, RF-KFSH&RC; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, King Fahad Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; drsabdulaziz@yahoo.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4381-8983

Ghada A. Al Janobi

MBBS, SBIM, SF Rheum; Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, Dhahran, Saudi; Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medicine, Qatif Central Hospital, Qatif, Saudi Arabia; dr.ghadaaljanobi@gmail.com

Abdulaziz Al Khalaf

MBBS, SF Rheum; Executive Health Medicine Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; dr.atalkhalaf@gmail.com

Bader Al Mehmadi

MBBS, SBIM, SF Rheum; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Majmaah University, Al-Majmaah, 11,952, Saudi Arabia; b.almehmadi@mu.edu.sa; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5609-9914

Mahasin Al Nassar

MBBS; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; dr.malnassar@gmail.com

Faisal AlBalawi

MBBS,SBIM, SF Rheum; Section of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; faisal1907@windowslive.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4563-4563

Abdullah S. AlFurayj

MBBS, SBIM, SF Rheum; Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medicine, Buraidah Central Hospital, B.C.H, Qassim, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia; abdullahalfurayj@gmail.com

Ahmed Hamdan Al-Jedai

Pharm.D., M.B.A., BCPS, FCCP, FAST, FASHP, FCCP, BCTxP; Deputyship of Therapeutic Affairs, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; ahaljedai@moh.gov.sa

Haya Mohammed Almalag

MSc, PhD; Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; halmalaq@ksu.edu.sa

Hajer Yousef Almudaiheem

Pharm.D., MSc; Deputyship of Therapeutic affairs, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; halmudaiheem@moh.gov.sa

Ali AlRehaily

M.D, FRCPC, MMedEdu; Department of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Security Forces Hospital Program, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; alialrehaily@yahoo.com; https://orcid.org/0000–0003-0661–7530

Mohammed A. Attar

MBBS, SBIM; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Al Hada Armed Forces Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia; attarmohammed@hotmail.com

Lina El Kibbi

MBBS; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Specialized Medical Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; linakibbe@hotmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1710-9996

Liana Fraenkel

MD, MPH; Berkshire Medical Center, Pittsfield, Massachusetts; Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, United States; liana.fraenkel@yale.edu; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6148-610X

Hussein Halabi

MBBS; Section of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; mfasel@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5174-8292

Manal Hasan

MBBS; Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia; mahasan@iau.edu.sa; https://orcid.org/000-0001-9342-7887

Jasvinder A. Singh

MBBS, MPH; Medicine Service, VA Medical Center, 700 19th St S, Birmingham, AL 35233 USA; Department of Medicine at the School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Shelby 121 1720 2nd Avenue South, Birmingham AL 35294–0110, USA; Department of Epidemiology at the UAB School of Public Health, 1665 University Blvd., Ryals Public Health Building, Birmingham, AL 35294–0022, USA; Jasvinder.md@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3485-0006

Funding

This project was funded by the Saudi Society of Rheumatology (SSR). The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MAO, HAR, EAA, JK, and SY oversaw the work, designed the process and methodology, coordinated the prioritization of questions, summarized the findings for the panel through the preparation of Evidence to Decision (EtD) tables, and coordinated panel meetings. MAO and EAA co-chaired the panel meetings. The KSA 2021 ACR RA adolopment working group prioritized questions and outcomes, provided relevant newly published studies, provided relevant contextual information, and participated in the final meeting in formulating the final recommendations. JK and EAA and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As it consists of a clinical practice guideline, the project did not require approval by an institutional review board (IRB).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MAO: grants or contracts (Abbvie, Pfizer, New Bridge, Roche and BMS), consulting fees (Abbvie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Hekma, Hoffman- La Roche, New Bridge, Pfizer), honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events (Abbvie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Hekma, Hoffman- La Roche, New Bridge, Pfizer), support for attending meetings and/or travel (Abbvie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gsk, Hekma, Hoffman- La Roche, New Bridge, Pfizer). HAR: honoraria for lectures and speaker fees (Pfizer, AbbVie, Lilly and Janssen), consulting fees (Pfizer, Lilly, AbbVie, Amgen, and Janssen). AAK: payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events (Pfizer, Abbvie, Lilly), grants or contracts (Pfizer, Lilly, Abbvie), support for attending meetings and/or travel (Pfizer, Abbvie, Lilly), participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board (Lilly, Pfizer), fellowship training program support (Pfizer). MAA: support for attending meetings and/or travel: Abbvie (Open Rheum meeting, Jeddah), Lilly (ADARCC, Dubai). JAS: consulting fees (Crealta/Horizon, Medisys, Fidia, PK Med, Two labs Inc., Adept Field Solutions, Clinical Care options, Clearview healthcare partners, Putnam associates, Focus forward, Navigant consulting, Spherix, MedIQ, Jupiter Life Science, UBM LLC, Trio Health, Medscape, WebMD, and Practice Point communications; and the National Institutes of Health and the American College of Rheumatology), payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events (on the speaker’s bureau of Simply Speaking), support for attending meetings and/or travel (support from OMERACT, an international organization that develops measures for clinical trials and receives arm’s length funding from 12 pharmaceutical companies, to attend their meeting every 2 years), leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid (steering committee member of the OMERACT, an international organization that develops measures for clinical trials and receives arm’s length funding from 12 pharmaceutical companies; chair of the Veterans Affairs Rheumatology Field Advisory Committee; editor and the Director of the UAB Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Satellite Center on Network Meta-analysis), stock or stock options (currently owned stock in TPT Global Tech, Vaxart pharmaceuticals, Atyu biopharma, Adaptimmune Therapeutics, GeoVax Labs, Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Enzolytics Inc., Seres Therapeutics and Charlotte’s Web Holdings, Inc; previously owned stock options in Amarin, Viking and Moderna pharmaceuticals).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Detailed timeline for the adolopment project.

Additional file 2.

Survey data

Additional file 3.

PANELVIEW instrument scores.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Khabsa, J., Yaacoub, S., Omair, M.A. et al. Methodology for the adolopment of recommendations for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Med Res Methodol 23, 224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-02031-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-023-02031-2