Abstract

Background

Process evaluations aim to understand how complex interventions bring about outcomes by examining intervention mechanisms, implementation, and context. While much attention has been paid to the methodology of process evaluations in health research, the value of process evaluations has received less critical attention. We aimed to unpack how value is conceptualised in process evaluations by identifying and critically analysing 1) how process evaluations may create value and 2) what kind of value they may create.

Methods

We systematically searched for and identified published literature on process evaluation, including guidance, opinion pieces, primary research, reviews, and discussion of methodological and practical issues. We conducted a critical interpretive synthesis and developed a practical planning framework.

Results

We identified and included 147 literature items. From these we determined three ways in which process evaluations may create value or negative consequences: 1) through the socio-technical processes of ‘doing’ the process evaluation, 2) through the features/qualities of process evaluation knowledge, and 3) through using process evaluation knowledge. We identified 15 value themes. We also found that value varies according to the characteristics of individual process evaluations, and is subjective and context dependent.

Conclusion

The concept of value in process evaluations is complex and multi-faceted. Stakeholders in different contexts may have very different expectations of process evaluations and the value that can and should be obtained from them. We propose a planning framework to support an open and transparent process to plan and create value from process evaluations and negotiate trade-offs. This will support the development of joint solutions and, ultimately, generate more value from process evaluations to all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

By examining intervention mechanisms, implementation, and context, process evaluations aim to understand how complex interventions bring about outcomes, shed light on unanticipated effects, and inform optimal integration into existing practice [1]. They are often conducted alongside outcome/effectiveness evaluations of complex interventions, including trials, pilot and feasibility studies, and implementation studies [1]. As recognition has grown that outcome/effectiveness evaluations often provided insufficient understanding of increasingly complex interventions and their effects in different contexts, process evaluations have become increasingly common [1].

Health research funding and commissioning bodies in the UK, including the Medical Research Council [1], National Institute for Health and Care Research [2], and Public Health England (now the UK Health Security Agency) [3], highlight benefits of including process evaluations with evaluations of complex interventions. Their importance is also recognised internationally [4, 5], and in other fields such as education [6]. However, process evaluations have potential disadvantages, including Hawthorne effects [3] and participant burden [7]. There are also possible challenges to conducting process evaluations, including under-resourcing [1], and the complexity of interventions and contexts being evaluated [8].

Questions about how to do process evaluations have been substantially addressed in the literature [1, 9], however to our knowledge the concept of the ‘value’ of process evaluations has not been systematically critically examined. In scoping for this review, we noted that authors often used value-laden but ambiguous adjectives, such as ‘high-quality’, ‘useful’ or ‘necessary’ to describe aspects of process evaluation and process evaluation knowledge, without defining these terms. Some aspects of value have been considered, including whether process evaluations can satisfactorily meet the aim of explaining outcomes [10], the value of pragmatic formative process evaluation [11], and the reported value of process evaluations in pragmatic randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [12]. O’Cathain et al. [13] investigated the value of combining RCTs and qualitative research but did not specifically examine process evaluations.

Recommendations and assertions about value are likely to reflect authors’ ontological and epistemological standpoints [8], and accordingly there are a variety of interpretations of ‘optimal’ process evaluation design and conduct in the literature. For example, the MRC process evaluation guidance [1] outlines ontological and epistemological debates about how aspects of process such as fidelity and intervention mechanisms may be conceptualised and studied. There are also paradigmatic differences in how complex interventions are conceptualised [14], which impact perspectives on what a process evaluation should be and do.

The concept of “value” in research is multifaceted, with diverse definitions such as”why we do things, what is important, and to whom” [15]; “the established collective moral principles and accepted standards of persons or a social group; principles, standards or qualities considered worthwhile or desirable” [16]; and “contribution, impact and success” [13]. Research value is also commonly described in terms of impact, and various typologies and frameworks for categorising and assessing research impact have been proposed [17,18,19,20]. Value is also often discussed in terms of financial value and reducing waste brought about through inefficient research processes [21, 22].

In this paper we take a broad perspective on value, aiming to examine the different ways in which the ‘value’ of process evaluation is conceptualised and consider how and why perspectives may differ within the field. Essentially, we seek to establish what may be gained from process evaluation and for whom, potential negative consequences of process evaluations, and what is considered to make a ‘good’ or ‘useful’ process evaluation. In agreement with O’Cathain et al.’s [13] rationale for studying the value of qualitative research in RCTs, we believe taking stock of, and critically analysing the value of process evaluation in its broadest sense is important to advance the methodological knowledge base.

We also believe developing a planning framework of process evaluation value provides practical assistance to researchers designing process evaluations. By making explicit at the outset different expectations of value by different stakeholders, potential tensions may be addressed [16]. Given that process evaluation researchers likely need to prioritise which aspects of interventions to examine and may choose from a wide selection of methods and frameworks [1], we suggest it pertinent to address the question ‘what do we want to get out of this process evaluation?’ before addressing the question ‘how are we going to do this process evaluation?’.

Our aims were to identify and critically analyse 1) how process evaluations may create value and negative consequences, and 2) what kind of value process evaluations may create.

Methods

We conducted a critical interpretive synthesis, broadly following the approach outlined by Dixon-Woods et al. [23]. Accordingly, we aimed to synthesise a diverse body of literature to develop a conceptual framework of a concept (value) that has not been consistently defined and operationalised in this context (process evaluation). The critical interpretive synthesis approach is inductive and interpretive, with the body of literature itself used as an object of analysis as well as individual papers, for example by questioning the inherent assumptions behind what is said and not said [23]. Dixon-Woods et al. [23] describe critical interpretive synthesis as an approach to review and not exclusively a method of synthesis, and do not prescribe a step-by-step method of operationalising their approach. Accordingly, we adopted the basic principles of their approach and adapted it to suit this body of literature, the aims of this review, and our available resources.

Since there has been little previous research into the value of process evaluations, we based this review on literature including process evaluation guidance, opinions about process evaluations, and discussion of methodological and practical issues. Thus, we considered what authors were stating about process evaluations and their value in texts such introductions, discussions, opinion pieces, and editorials, as well as any research findings we did locate in the searches.

Search strategy

We searched for literature on process evaluation, including guidance, opinion pieces, primary research, reviews, and discussion of methodological and practical issues.

We searched the following sources:

-

1.

Reference lists of four major process evaluation frameworks [1, 4, 9, 24]

-

2.

Forward citation searches of the same four process evaluation frameworks using Web of Science and Google Scholar

-

3.

Medline database search for articles with term “process evaluation*” in title; limited to English language

-

4.

Scopus database search for articles with term “process evaluation*” in title; limited to English language; subjects limited to medicine, social sciences, nursing, psychology, health professions, pharmacology, dentistry

-

5.

ETHOS database for PhD theses with term ‘process evaluation’ in the title (excluded in updated search)

-

6.

Literature items not located by the searches but which we knew contained relevant information about process evaluation from our work in this field, such as broader guidance documents about evaluation methods containing sections on process evaluation.

CF originally conducted the search in September 2017 and updated it in January 2021. In the updated search we excluded the ETHOS database search due to time constraints.

Definition of process evaluation

We used the definition of process evaluation provided in the Medical Research Council’s process evaluation guidance [1] when selecting items for inclusion: ‘a study which aims to understand the functioning of an intervention, by examining implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors’. We chose this definition because the MRC’s process evaluation guidance is extensive and widely cited, and we considered its definition comprehensive.

Screening, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

We did not aim to include every item of relevant literature, rather to systematically search for and select literature most relevant to our aims. For example, literature on mixed-methods research and process evaluation concepts such as fidelity would have been relevant, however we only included those focusing on the overall concept of process evaluation. Although we only searched health-related sources, we did not limit inclusion to the field of health.

Inclusion criteria

We included published literature (including editorials, letters, commentaries, book chapters, research articles) that met all the following criteria:

-

1.

Used the term ‘process evaluation’ in line with the above definition

-

2.

Discussed process evaluation in any field, providing ‘process evaluation’ met the definition above

-

3.

Discussed process evaluation accompanying any kind of outcome/effectiveness evaluation, intervention development work, or standalone process evaluation

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Items in which term ‘process evaluation’ is used to describe an evaluation not meeting the definition in our review

-

2.

Items which only reported process evaluation protocols or findings – these were only included if they also discussed wider process evaluation issues (e.g. methodological, operational)

-

3.

No full-text available online

-

4.

Not in English language

Results screening

CF screened the titles and abstracts of all results, obtaining full texts where necessary to aid decisions.

Data analysis and synthesis

We did not conduct quality appraisal of the included literature as we selected diverse items such as editorials, and synthesised whole texts as qualitative data, rather than aggregated research findings.

This review was inductive and we did not start out with a priori concepts or categories about how process evaluations create value or the type of value they create. We kept in mind however the value system of ‘process’, ‘substantive’ and ‘normative’ values outlined by Gradinger et al. [16] to sensitise us to values possibly stemming from 1) the conduct of process evaluation; 2) the impact of process evaluation or 3) the perceived intrinsic worth of process evaluation, respectively. We considered ‘value’ in its broadest possible sense, and examined what authors stated, implied, and discussed about what may result from a process evaluation (both positive and negative), the purposes of process evaluation, and what makes a ‘good’ or ‘useful’ process evaluation.

Following the critical interpretive synthesis approach [23], we also aimed to be critical through questioning the nature of assumptions and proposed solutions relating to process evaluation issues discussed in the literature. This enabled us to examine how authors covering diverse fields and types of process evaluation variously perceived value in different contexts.

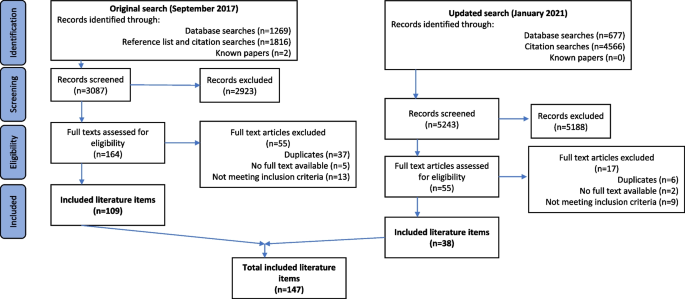

CF initially undertook this work as part of her PhD from the original search results in September 2017 with 109 included items (see Fig. 1). Following initial reading of all items to gain familiarity she began the detailed analysis of approximately one third of randomly selected papers (n = 40) by extracting sections of text relating to how process evaluations create value and types of value that may be created. She organised these into an initial coding framework, using NVivo to manage the data and noting impressions of the overall literature. She then used this framework to code the remaining items (n = 69), amending the framework as necessary. A further 38 literature items were identified following the updated search in January 2021 (see Fig. 1), which CF coded in the same way, further refining the framework.

Dixon-Woods et al. [23] describe the benefits of a multidisciplinary team approach to the whole review and synthesis process. As this paper reports work initiated through individual doctoral work we decided to strengthen and deepen the analysis by independently double coding a total of 36 of the total 147 items (approximately 25%). We used purposive sampling to select the 36 papers for double coding, selecting papers with varied characteristics (year of publication, country of lead author, field of practice, and focus of paper). Four authors coded nine papers each using the coding framework developed by CF, also noting any new themes, interpretations, and areas of disagreement. We brought these to a team discussion to refine the themes and develop the final analysis. We developed this double coding approach as a pragmatic solution to incorporating multiple perspectives into the synthesis, based on our experience of conducting similar narrative reviews and team qualitative data analysis.

From the resulting themes, notes on interpretations, and team discussions we created a narrative and conceptual framework of our analysis, along with a practical planning framework for researchers designing process evaluations.

Results

Search results

We included 147 literature items, and our search results are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1 shows characteristics of the included literature items, with a detailed summary table in additional file 1.

Critical interpretive synthesis overview

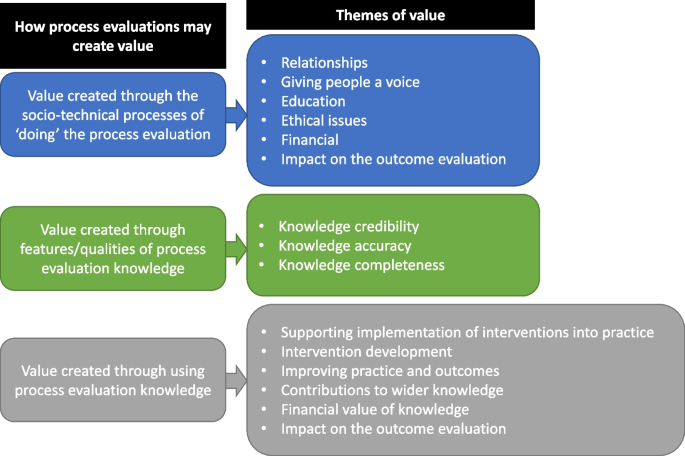

Figure 2 provides an overview of the findings of this synthesis.

As shown in Fig. 2, we identified three ways in which process evaluations may create value: 1) through the socio-technical processes of ‘doing’ the process evaluation, 2) through the features/qualities of process evaluation knowledge, and 3) through using process evaluation knowledge.

From these three ways in which process evaluations may create value we identified 15 value themes. Many of these 15 themes included both positive and potentially negative consequences of process evaluations. Value and negative consequences may be created for many different stakeholders, including research participants, researchers, students, funders, research commissioners, intervention staff, organisations, practice settings, research sites, interventions, practice outcomes, and outcome evaluations.

However, as shown in the box describing process evaluation characteristics in Fig. 2, process evaluations may vary widely in terms of 1) which processes are evaluated 2) how these processes are evaluated, 3) the practical conduct of the process evaluation, and 4) how process evaluation knowledge is disseminated. Value is therefore at least partially contingent on the characteristics of individual process evaluations.

Finally, process evaluations are designed, conducted, and their knowledge applied in many different contexts. We found different stakeholders in different contexts may have different perspectives on what is valuable, meaning the value created by process evaluations is subjective. We therefore noted potential tensions and payoffs between certain values.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the themes of value and shows how the themes relate to the three identified ways in which value may be created. We describe these findings in detail in Tables 2, 3, and 4, including subthemes and examples from the synthesised literature. We then end this results section with a discussion of tensions between values.

Value created through the socio-technical processes of ‘doing’ the process evaluation

Many social and technical processes are involved in the design, conduct, and dissemination of process evaluation, and thus value and negative consequences may arise from the ‘doing’ of the process evaluation. Examples of socio-technical processes include collecting observational data at a research site, inviting a trial participant to participate in a process evaluation, and designing a questionnaire. These are all carried out by multiple human actors (for example researchers and research participants) using a variety of knowledge products (for example evaluation frameworks and research protocols). In Fig. 2, these processes and actors are summarised under the heading ‘process evaluation characteristics’. Taking a stance that value is situated and formed out of context, the way in which these processes evolve have a direct impact on the value that can be derived from a process evaluation. We identified six themes of value stemming from socio-technical processes:

-

Relationships

-

Giving people a voice

-

Education

-

Ethical issues

-

Financial

-

Impact on the outcome evaluation

Table 2 shows the themes, subthemes, and examples of how socio-technical processes may create value from process evaluations.

Value related to the features/qualities of process evaluation knowledge

The second way in which process evaluations may create value relates to the features and perceived qualities of the knowledge they produce. The process evaluation characteristics outlined in Fig. 2 clearly lead to different kinds of process evaluation knowledge being produced, for example qualitative or quantitative. We identified three themes of value which relate to the features and qualities of process evaluation knowledge:

-

Knowledge credibility

-

Knowledge accuracy

-

Knowledge completeness

Table 3 outlines how process evaluation variables may impact on the perceived value of the knowledge that is produced.

Inevitably, some of the ways in which process evaluation knowledge may be inaccurate or incomplete described in Table 3 may be unavoidable. For example, it is likely impossible for financial, practical, and ethical reasons for process evaluations to investigate every potentially important aspect of an intervention [1, 41]. Issues such as gatekeeping, self-selection bias, and social desirability bias are research challenges not unique to process evaluations. However, the literature suggests that process evaluation reporting is often suboptimal, with detail on methods lacking, choices about methodology and areas of enquiry not justified [9, 34, 40, 55, 63, 71, 97, 131], and limited discussion of quality, validity, and credibility [9, 40, 63, 90]. This suggests inaccuracy and incompleteness of process evaluation knowledge may not always be acknowledged.

Furthermore, some authors suggest that some process evaluation researchers do not recognise that their methods may be overly simplistic portrayals of reality, and therefore fail to consider important aspects of process [40, 59]. Some papers conceptualised process evaluation components as highly complex, suggesting that methods such as ethnography [34], realist evaluation [46], and the use of theoretical frameworks such as normalisation process theory [132] were necessary to fully capture what was going on. At the opposite end of the spectrum some papers conceptualised process evaluation components simplistically, for example equating whether or not intervention recipients enjoyed intervention components with their effectiveness [91]. A potential negative consequence of process evaluations therefore may be if knowledge is uncritically presented as providing explanations when researchers did not account for all factors or the true level of complexity. For example, assessing single dimensions of implementation may lead to ‘type III errors’ through incorrectly attributing a lack of intervention effect to a single implementation factor, when the actual cause was not investigated [40, 117].

Value created by using process evaluation knowledge

The third way in which value and negative consequences may be created is through using the knowledge produced by process evaluations. Process evaluation knowledge may be used and applied after the evaluation. It may also be used formatively to make changes to interventions, implementation, contexts, and evaluation processes during the evaluation. Some experimental outcome evaluation methods prevent formative use of knowledge to maintain internal and external validity. We identified six themes of value stemming from the use of process evaluation knowledge:

-

Supporting implementation of interventions into practice

-

Informing development of interventions

-

Improving practice and outcomes

-

Contribution to wider knowledge

-

Financial value of knowledge

-

Impact on the outcome evaluation

These are described along with sub-themes and examples in Table 4.

Tensions within and between values

As well as identifying how process evaluations may create value and themes of value, we found that the concept of value in process evaluations is subjective and context-dependent, and there are tensions within and between values.

The value of process evaluation is not pre-existing but enacted and created through ongoing negotiation between those with a stake in what is being evaluated. Through designing and conducting a process evaluation and disseminating and using its knowledge, process evaluation actors and knowledge products may directly or indirectly create value and negative consequences for many different stakeholders and bystanders in different contexts. These include people and organisations who participate in research, conduct research, use research findings, receive interventions, work in research and practice settings, fund research, regulate research, or are simply present where process evaluations are being conducted. These groups and organisations have different expectations, values, and needs; and there is also variability within groups and organisations. This creates the potential for tension between expectations, values, and needs of different stakeholders.

We identified two broad perspectives on value. In the first, process evaluations are primarily valued for supporting the scientific endeavour of outcome evaluations, particularly trials. Examples of this include process evaluations being conducted to minimally contaminate or threaten interventions and outcome evaluations, with the generated knowledge applied post-hoc and providing retrospective understanding [87, 118]. Formative monitoring and correction of implementation aims to ensure internal validity [24, 44, 48, 77, 93, 94]. Value is framed around meeting the needs of the outcome evaluation, such as through complementing trial findings [9], and the perceived utility of findings may be contingent on what happens in an outcome evaluation [133]. They are also framed around the needs of researchers and systematic reviewers. For example, calls for them to include set components to make them less daunting to conduct and enable easier cross-study comparison [1, 5, 24, 57, 58].

In the second perspective process evaluations are mostly valued for formatively contributing to intervention development, improving practice, and forging relationships with stakeholders. Evaluating implementation may allow for the adaptation and tailoring of interventions to local contexts [1], which may result in them being more patient-centred [126], with better fit and feasibility in local settings [55]. Process evaluations may be seen as opportunities to utilise methodologies with different ontological and epistemological assumptions to RCTs, with flexible designs that are tailored to the uniqueness of each intervention and setting [34, 67]. These process evaluations are more likely to find multiple nuanced answers, reflecting assumptions that reality is unpredictable and complex, and that interventions are most effective when adapted to different contexts. These seem more concerned with giving participants voices and uncovering messy realities, developing effective sustainable interventions, and through these, improving outcomes [33, 60].

Some authors give examples of process evaluation designs which may capitalise on both perspectives on value. In-depth realist formative process evaluations at the stage of piloting interventions incorporate the benefits of developing and theorising effective, sustainable, adaptable interventions that are tailored to local contexts, which can then be tested in a rigorous outcome evaluation [46]. Pragmatic formative process evaluations theorise interventions which are already in practice and optimise implementation in readiness for outcome evaluations [11, 35].

The literature also contains examples of tensions between these two perspectives. For example, process evaluation methods that enhance engagement with participants may increase the effect of the intervention, which may be seen as desirable [32] or a problematic Hawthorne effect [1]. If data from summative process evaluations reveal problems with interventions or implementation during the evaluation, this can raise ethical and methodological dilemmas about whether to intervene [42, 43]. Riley et al. suggested process data monitoring committees as forums for debating such contentious scenarios to address these issues [43]. Others highlighted the importance of stakeholders having clear expectations about the value that process evaluations may create and when, to avoid tensions stemming from unmet expectation. Examples include establishing clear mandates with intervention staff about when they will receive feedback on their delivery [31] and how their data will improve interventions [89].

Discussion

Summary of findings

Process evaluations do not have value a priori. Their value is contingent on the features and qualities of the knowledge they produce, and the socio-technical processes used to produce that knowledge. There is also potential to create consequences that may be perceived negatively. However, there are not simple definitive answers to the questions ‘what kind of value do/should process evaluations create?’ or ‘how do/should process evaluations create value?’. This is because:

-

The label ‘process evaluation’ may be applied to many different types of studies producing diverse kinds of knowledge and using diverse socio-technical processes.

-

Process evaluations are undertaken in different research and practice contexts in which different kinds of knowledge and socio-technical processes may be perceived as more or less valuable or desirable.

-

Process evaluations are undertaken by researchers with differing ontological and epistemological standpoints and research traditions, who have different views on what constitutes high-quality, useful, and valuable knowledge.

Theoretical considerations

Our analysis shows that part of the challenge of interpreting the value of process evaluation is that researchers and other stakeholders are debating value from different ontological and epistemological starting points. These tensions resonate with the wider literature on qualitative research with quantitative outcome evaluation [13, 45, 134, 135], and how complex interventions should be conceptualised and evaluated [136,137,138].

There are tensions between values, particularly payoffs between optimising value to outcome evaluations and triallists, and optimising value to intervention development and relationship-building. While the professed aims of both are to improve practice and outcomes for intervention recipients and to advance knowledge, the beliefs about how this is best achieved often differ. For example, process evaluation researchers with a more positivist stance likely believe a positive primary outcome result with high internal validity is most likely to ultimately improve practice and outcomes. They may therefore value process evaluations which minimally contaminate interventions and measure fidelity. Process evaluation researchers with a more interpretivist stance likely believe in-depth understanding of the experiences of intervention recipients is more likely to ultimately improve practice and outcomes. They could therefore value process evaluations which engage participants in more in-depth data collection methods.

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to debate the relative merits of these paradigmatic differences, ontological and epistemological perspectives appear to strongly influence perspectives on what kind of knowledge it is valuable for process evaluations to generate. This demonstrates the importance of making ontological and epistemological perspectives explicit when discussing how to design and conduct process evaluations, for example in process evaluation guidance and frameworks [8].

We also encourage researchers to take stock of these different perspectives on value and critically reflect on whether concentrating value on one perspective potentially misses the opportunities to create value offered by another. For example, through the aim of minimally contaminating interventions are opportunities missed to engage stakeholders who could assist with intervention improvement and post-evaluation implementation? Are there potential ways to combine both approaches to process evaluation? As highlighted in our analysis, in-depth formative process evaluations in the intervention development and feasibility testing stages offer this opportunity [46]. Furthermore, the newly updated Medical Research Council Framework for evaluating complex interventions [138] (published after we completed the searches for this review) states “A trade-off exists between precise unbiased answers to narrow questions and more uncertain answers to broader, more complex questions; researchers should answer the questions that are most useful to decision makers rather than those that can be answered with greater certainty”. This suggests pragmatic weighing-up of the overall value created by process evaluations will become increasingly significant.

Practical applications

Our findings have practical applications for researchers designing process evaluations to be intentional in creating value and avoiding negative consequences. We recommend that since process evaluations vary widely, before researchers ask: ‘how do we do this process evaluation? they ask: ‘what do we want to get out of this process evaluation?’. Process evaluations will create value, and potentially negative consequences regardless of whether it is planned, so we suggest purposefully and explicitly preparing to create value in conjunction with stakeholders.

Figure 4 shows a planning framework to be used in conjunction with Fig. 3 and the analysis in this paper to aid this process. As would be good practice in any research, we recommend these discussions include as many stakeholders as possible, including intended beneficiaries of research, also reflecting the possible diversity of research backgrounds and epistemological standpoints within research teams. This would help guide decisions around design, conduct, and dissemination by making expectations of value explicit from the outset, addressing potential tensions, and ensure contextual fit. While the nature of any accompanying outcome evaluation will influence expectations of value, it is useful for stakeholders to be aware of potential payoffs and ensure there is a shared vision for creating value. This will likely also aid researchers to narrow the focus of process evaluation to make it more feasible and best allocate resources, as well as highlighting its value to stakeholders without relevant knowledge and experience.

Strengths and limitations

We included a large number of literature items relating to process evaluations in diverse contexts, which enabled us to synthesise a broad range of perspectives on value and highlight how value may be context dependent. This will enable readers to apply findings to their own contexts. Nonetheless our review does not include all literature that could have been informative, and therefore the values and issues identified are unlikely to be exhaustive. Furthermore, author texts we extracted as data for our review may have been influenced by expectations and limitations of publishing journals. Exploring the concept of value by reviewing the literature only captures perspectives which authors have decided to publish, and other aspects of value are likely to be uncovered through empirical study of process evaluation practice.

Although we have outlined our review methods as explicitly as possible, in line with critical interpretive synthesis the review was by nature interpretive and creative, therefore full transparency about step-by-step methods is not possible [23]. We present our interpretation of this body of literature and acknowledge that this will have been influenced by our pre-existing opinions about process evaluation. Nonetheless our team included researchers from different backgrounds, and through a double-coding process and reflective team discussion ensured we did not unduly focus on one aspect of value or prioritise certain perspectives.

Conclusions

Process evaluations vary widely and different stakeholders in different contexts may have different expectations and needs. This critical interpretive synthesis has identified potential sources of and themes of value and negative consequences from process evaluations, and critically analysed potential tensions between values. Accommodating all needs and expectations of different stakeholders within a single process evaluation may not be possible, but this paper offers a framework to support an open transparent process to plan and create value and negotiate trade-offs. This supports the developments of joint solutions and, ultimately, generate more value from process evaluations to all.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

randomised controlled trial

References

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance. London: MRC Population Health Science Network; 2014.

Raine R, Fitzpatrick R, Barratt H, Bevan G, Black N, Boaden R, et al. Challenges, solutions and future directions in the evaluation of service innovations in health care and public health. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2016;4(16).

Public Health England. Process evaluation: evaluation in health and wellbeing. 2018. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/evaluation-in-health-and-wellbeing-process Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Baranowski T, Stables G. Process evaluations of the 5-a-Day projects. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(2):157–66.

Bakker FC, Persoon A, Reelick MF, van Munster BC, Hulscher M, Olde RM. Evidence from multicomponent interventions: value of process evaluations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(5):844–5.

Humphrey N, Lendrum A, Ashworth E, Frearson K, Buck R, Kerr K. Implementation and process evaluation (IPE) for interventions in educational settings: An introductory handbook. London, UK: Education Endowment Foundation; 2016.

Griffin T, Clarke J, Lancashire E, Pallan M, Adab P. Process evaluation results of a cluster randomised controlled childhood obesity prevention trial: the WAVES study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):681.

Masterson-Algar P, Burton C, Rycroft-Malone J. The generation of consensus guidelines for carrying out process evaluations in rehabilitation research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):180.

Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, Foy R. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials. 2013;14(1):15.

Munro A, Bloor M. Process evaluation: the new miracle ingredient in public health research? Qual Res. 2010;10(6):699–713.

Evans R, Scourfield J, Murphy S. Pragmatic, formative process evaluations of complex interventions and why we need more of them. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(10):925–6.

French C, Pinnock H, Forbes G, Skene I, Taylor SJ. Process evaluation within pragmatic randomised controlled trials: what is it, why is it done, and can we find it?—a systematic review. Trials. 2020;21(1):1–16.

O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Drabble SJ, Rudolph A, Goode J, Hewison J. Maximising the value of combining qualitative research and randomised controlled trials in health research: the QUAlitative Research in Trials (QUART) study–a mixed methods study. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(38):1–197, v−vi.

Moore GF, Evans RE, Hawkins J, Littlecott H, Melendez-Torres G, Bonell C, et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation. 2019;25(1):23–45.

Haywood K, Lyddiatt A, Brace-McDonnell SJ, Staniszewska S, Salek S. Establishing the values for patient engagement (PE) in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) research: an international, multiple-stakeholder perspective. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(6):1393–404.

Gradinger F, Britten N, Wyatt K, Froggatt K, Gibson A, Jacoby A, et al. Values associated with public involvement in health and social care research: a narrative review. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):661–75.

Greenhalgh T. Research impact: a narrative review. BMC Med. 2016;14:78.

Rycroft-Malone J, Wilkinson JE, Burton CR, Andrews G, Ariss S, Baker R, et al. Implementing health research through academic and clinical partnerships: a realistic evaluation of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):74.

Raftery J, Hanney S, Greenhalgh T, Glover M, Blatch-Jones A. Models and applications for measuring the impact of health research: update of a systematic review for the Health Technology Assessment programme. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20(76):1–254.

Buxton M, Hanney S. How can payback from health services research be assessed? Journal of Health Services Research. 1996;1(1):35–43.

The Lancet Neurology. Maximising the value of research for brain health. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(11):1065.

National Institute for Health Research. Adding value in research. 2021. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/adding-value-in-research/2785620. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):1–13.

Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: an overview. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco Jossey-Bass; 2002.

Roe K, Roe K. Dialogue boxes: a tool for collaborative process evaluation. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(2):138–50.

Platt S, Gnich W, Rankin D, Ritchie D, Truman J, Backett-Milburn K. Applying process evaluation: Learning from two research projects. 2009. In: Thorogood M, Coombes Y, editors. Evaluating Health Promotion: Practice and Methods. Oxford Scholarship Online.

Gensby U, Braathen TN, Jensen C, Eftedal M. Designing a process evaluation to examine mechanisms of change in return to work outcomes following participation in occupational rehabilitation: a theory-driven and interactive research approach. Int J Disabil Manag. 2018;13:1–16.

Tolma EL, Cheney MK, Troup P, Hann N. Designing the process evaluation for the collaborative planning of a local turning point partnership. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(4):537–48.

Kelley SD, Van Horn M, DeMaso DR. Using process evaluation to describe a hospital-based clinic for children coping with medical stressors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(7):407–15.

Simuyemba MC, Ndlovu O, Moyo F, Kashinka E, Chompola A, Sinyangwe A, et al. Real-time evaluation pros and cons: Lessons from the Gavi Full Country Evaluation in Zambia. Evaluation. 2020;26(3):367–79.

Howarth E, Devers K, Moore G, O'Cathain A, Dixon-Woods M. Contextual issues and qualitative research. 2016. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2016;4(16):105–20.

Franzen S, Morrel-Samuels S, Reischl TM, Zimmerman MA. Using process evaluation to strengthen intergenerational partnerships in the youth empowerment solutions program. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(4):289–301.

Cornwall A, Aghajanian A. How to find out what’s really going on: understanding impact through participatory process evaluation. World Dev. 2017;99:173–85.

Bunce AE, Gold R, Davis JV, McMullen CK, Jaworski V, Mercer M, et al. Ethnographic process evaluation in primary care: explaining the complexity of implementation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–10.

Gobat NH, Littlecott H, Williams A, McEwan K, Stanton H, Robling M, et al. Developing whole-school mental health and wellbeing intervention through pragmatic formative process evaluation: a case-study of innovative local practice within the school health research network. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:154.

Chrisman NJ, Senturia K, Tang G, Gheisar B. Qualitative process evaluation of urban community work: a preliminary view. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(2):232–48.

Viadro CI, Earp JAL, Altpeter M. Designing a process evaluation for a comprehensive breast cancer screening intervention: challenges and opportunities. Eval Program Plann. 1997;20(3):237–49.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350: h1258.

Ellard DR, Taylor SJC, Parsons S, Thorogood M. The OPERA trial: a protocol for the process evaluation of a randomised trial of an exercise intervention for older people in residential and nursing accommodation. Trials. 2011;12(1):28.

Humphrey N, Lendrum A, Ashworth E, Frearson K, Buck R, Kerr K. Implementation and process evaluation (IPE) for interventions in educational settings: A synthesis of the literature. London, UK: Education Endowment Foundation; 2016.

Lytle LA, Davidann BZ, Bachman K, Edmundson EW, Johnson CC, Reeds JN, et al. CATCH: Challenges of conducting process evaluation in a multicenter trial. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(1_suppl):S129-S41.

Murtagh M, Thomson R, May C, Rapley T, Heaven B, Graham R, et al. Qualitative methods in a randomised controlled trial: the role of an integrated qualitative process evaluation in providing evidence to discontinue the intervention in one arm of a trial of a decision support tool. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(3):224–9.

Riley T, Hawe P, Shiell A. Contested ground: how should qualitative evidence inform the conduct of a community intervention trial? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(2):103–10.

Tolma EL, Cheney MK, Chrislip DD, Blankenship D, Troup P, Hann N. A systematic approach to process evaluation in the Central Oklahoma turning point (cotp) partnership. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42(3):130–41.

Jansen YJFM, Foets MME, de Bont AA. The contribution of qualitative research to the development of tailor-made community-based interventions in primary care: a review. Eur J Pub Health. 2009;20(2):220–6.

Brand SL, Quinn C, Pearson M, Lennox C, Owens C, Kirkpatrick T, et al. Building programme theory to develop more adaptable and scalable complex interventions: realist formative process evaluation prior to full trial. Evaluation. 2019;25(2):149–70.

Byng R, Norman I, Redfern S. Using realistic evaluation to evaluate a practice-level intervention to improve primary healthcare for patients with long-term mental illness. Evaluation. 2005;11(1):69–93.

Audrey S, Holliday J, Parry-Langdon N, Campbell R. Meeting the challenges of implementing process evaluation within randomized controlled trials: the example of ASSIST (A Stop Smoking in Schools Trial). Health Educ Res. 2006;21(3):366–77.

Butterfoss FD. Process evaluation for community participation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27(1):323–40.

Reynolds J, DiLiberto D, Mangham-Jefferies L, Ansah E, Lal S, Mbakilwa H, et al. The practice of “doing” evaluation: lessons learned from nine complex intervention trials in action. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):75.

Nagy MC, Johnson RE, Vanderpool RC, Fouad MN, Dignan M, Wynn TA, et al. Process evaluation in action: lessons learned from Alabama REACH 2010. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2008;2(1):6.

Bakker FC, Persoon A, Schoon Y, Olde Rikkert MGM. Uniform presentation of process evaluation results facilitates the evaluation of complex interventions: development of a graph: Presenting process evaluation’s results. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(1):97–102.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337(7676):979–83.

Biron CaK-M M. Process evaluation for organizational stress and well-being interventions: implications for theory, method, and practice. Int J Stress Manag. 2014;21(1):85–111.

Masterson-Algar P, Burton CR, Rycroft-Malone J. Process evaluations in neurological rehabilitation: a mixed-evidence systematic review and recommendations for future research. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11): e013002.

Palmer VJ, Piper D, Richard L, Furler J, Herrman H. Balancing opposing forces—a nested process evaluation study protocol for a stepped wedge designed cluster randomized controlled trial of an experience based codesign intervention the CORE study. Int J Qual Methods. 2016;15(1):160940691667221.

Yeary KH, Klos LA, Linnan L. The examination of process evaluation use in church-based health interventions: a systematic review. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):524–34.

Scott SD, Rotter T, Hartling L, Chambers T, Bannar-Martin KH. A protocol for a systematic review of the use of process evaluations in knowledge translation research. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):149.

Ferm L, Rasmussen CDN, Jørgensen MB. Operationalizing a model to quantify implementation of a multi-component intervention in a stepped-wedge trial. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):26.

Gray CS, Shaw J. From summative to developmental: incorporating design-thinking into evaluations of complex interventions. Journal of Integrated Care. 2019.

Lee BK, Lockett D, Edwards N. Gauging alignments: an ethnographically informed method for process evaluation in a community-based intervention. 2011;25(2):1–27.

Grant A, Dreischulte T, Treweek S, Guthrie B. Study protocol of a mixed-methods evaluation of a cluster randomized trial to improve the safety of NSAID and antiplatelet prescribing: data-driven quality improvement in primary care. Trials. 2012;13(1):154.

Morgan-Trimmer S. Improving process evaluations of health behavior interventions: learning from the social sciences. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(3):295–314.

Renger R, Foltysova J. Deliberation-derived process (DDP) evaluation. Evaluation Journal of Australasia. 2013;13(2):9.

Maar MA, Yeates K, Perkins N, Boesch L, Hua-Stewart D, Liu P, et al. A framework for the study of complex mHealth Interventions in diverse cultural settings. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2017;5(4):e47.

Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J. Intervention description is not enough: evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in randomised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials. 2012;13(1):95.

Morgan-Trimmer S, Wood F. Ethnographic methods for process evaluations of complex health behaviour interventions. Trials. 2016;17(1):232.

Oakley A. Evaluating processes a case study of a randomized controlled trial of sex education. Evaluation (London, England 1995). 2004;10(4):440–62.

Cunningham LE. The value of process evaluation in a community-based cancer control program. Eval Program Plann. 2000;23(1):13–25.

Buckley L, Sheehan M. A process evaluation of an injury prevention school-based programme for adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(3):507–19.

Moore G. Developing a mixed methods framework for process evaluations of complex interventions: the case of the National Exercise Referral Scheme policy trial in Wales. [dissertation on the internet] Cardiff: University of Cardiff; 2010 [cited 15 Mar 2022] Available from: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/55051/

Byng R, Norman I, Redfern S, Jones R. Exposing the key functions of a complex intervention for shared care in mental health: case study of a process evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):274.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43(3–4):267–76.

De Silva MJ, Breuer E, Lee L, Asher L, Chowdhary N, Lund C, et al. Theory of Change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the medical research council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials. 2014;15(1):267.

McGill E, Marks D, Er V, Penney T, Petticrew M, Egan M. Qualitative process evaluation from a complex systems perspective: a systematic review and framework for public health evaluators. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11): e1003368.

Haynes A, Brennan S, Redman S, Williamson A, Gallego G, Butow P. Figuring out fidelity: a worked example of the methods used to identify, critique and revise the essential elements of a contextualised intervention in health policy agencies. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):23.

Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Meyers DC. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: the ACT trial experience. Int J Behav Nutr. 2009;6(1):79.

O’Cathain A, Goode J, Drabble SJ, Thomas KJ, Rudolph A, Hewison J. Getting added value from using qualitative research with randomized controlled trials: a qualitative interview study. Trials. 2014;15(1):215.

Griffin TL, Pallan MJ, Clarke JL, Lancashire ER, Lyon A, Parry JM, et al. Process evaluation design in a cluster randomised controlled childhood obesity prevention trial: the WAVES study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):112.

Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, Bounthavong M, Reardon CM, Damschroder LJ, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1–12.

Strange V, Allen E, Oakley A, Bonell C, Johnson A, Stephenson J, et al. Integrating process with outcome data in a randomized controlled trial of sex education. Evaluation. 2006;12(3):330–52.

Wight D, Obasi A. Unpacking the ‘black box’: the importance of process data to explain outcomes. In: Stephenson JM, Bonell C, Imrie J, editors. Effective sexual health interventions : issues in experimental evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Leeming D, Marshall J, Locke A. Understanding process and context in breastfeeding support interventions: the potential of qualitative research understanding process in breastfeeding support. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(4): e12407.

Haynes A, Brennan S, Carter S, O’Connor D, Schneider CH. Protocol for the process evaluation of a complex intervention designed to increase the use of research in health policy and program organisations (the SPIRIT study). Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):113.

Helitzer D, Yoon SJ, Wallerstein N, Garcia‐Velarde LDy. The role of process evaluation in the training of facilitators for an adolescent health education program. J Sch Health. 2000;70(4):141–7.

Irvine L, Falconer DW, Jones C, Ricketts IW, Williams B. Can text messages reach the parts other process measures cannot reach: an evaluation of a behavior change intervention delivered by mobile phone? PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12): e52621.

Hulscher MEJL, Laurant MGH, Grol RPTM. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(1):40–6.

Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2006;332(7538):413–6.

Odendaal WA, Marais S, Munro S, van Niekerk A. When the trivial becomes meaningful: reflections on a process evaluation of a home visitation programme in South Africa. Eval Program Plann. 2008;31(2):209–16.

Cheng KK, Metcalfe A. Qualitative methods and process evaluation in clinical trials context: where to head to? Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1):1609406918774212.

Branscum P, Hayes L. The utilization of process evaluations in childhood obesity intervention research: a review of reviews. International Journal of Child Health and Nutrition. 2013;2(4):270–80.

Boeije HR, Drabble SJ, O’Cathain A. Methodological challenges of mixed methods intervention evaluations. methodology. Eur J Res Methods Soc Sci. 2015;11(4):119–25.

McGraw SA, Stone EJ, Osganian SK, Elder JP, Perry CL, Johnson CC, et al. Design of process evaluation within the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH). Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(1_suppl):S5-S26.

Tuchman E. A model-guided process evaluation: Office-based prescribing and pharmacy dispensing of methadone. Eval Program Plann. 2008;31(4):376–81.

Limbani F. Process evaluation in the field: global learnings from seven implementation research hypertension projects in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):953.

Grant A, Bugge C, Wells M. Designing process evaluations using case study to explore the context of complex interventions evaluated in trials. Trials. 2020;21(1):1–10.

Nielsen K, Randall R. Opening the black box: presenting a model for evaluating organizational-level interventions. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2013;22(5):601–17.

Leontjevas R, Gerritsen DL, Koopmans RTCM, Smalbrugge M, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ. Process evaluation to explore internal and external validity of the “Act in Case of Depression” care program in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(5):488.e1-.e8.

Frost J, Wingham J, Britten N, Greaves C, Abraham C, Warren FC, et al. The value of social practice theory for implementation science: learning from a theory-based mixed methods process evaluation of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Ekambareshwar M, Ekambareshwar S, Mihrshahi S, Wen LM, Baur LA, Laws R, et al. Process evaluations of early childhood obesity prevention interventions delivered via telephone or text messages: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18(1):1–25.

Lee H, Contento IR, Koch P. Using a systematic conceptual model for a process evaluation of a middle school obesity risk-reduction nutrition curriculum intervention: choice, control & change. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(2):126–36.

Segrott J, Murphy S, Rothwell H, Scourfield J, Foxcroft D, Gillespie D, et al. An application of extended normalisation process theory in a randomised controlled trial of a complex social intervention: process evaluation of the strengthening families Programme (10–14) in Wales. UK SSM-population health. 2017;3:255–65.

Nielsen JN, Olney DK, Ouedraogo M, Pedehombga A, Rouamba H, Yago-Wienne F. Process evaluation improves delivery of a nutrition-sensitive agriculture programme in Burkina Faso. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(3): e12573.

Alia KA, Wilson DK, McDaniel T, St. George SM, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Smith K, et al. Development of an innovative process evaluation approach for the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss trial in African American adolescents. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2015;49(Supplement C):106–16.

Diaz T, Guenther T, Oliphant NP, Muñiz M, i CCMSioetg. A proposed model to conduct process and outcome evaluations and implementation research of child health programs in Africa using integrated community case management as an example. Journal of Global Health. 2014;4(2):020409.

May CR, Mair FS, Dowrick CF, Finch TL. Process evaluation for complex interventions in primary care: understanding trials using the normalization process model. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8(1):42.

Evans R, Scourfield J, Murphy S. The unintended consequences of targeting: young people’s lived experiences of social and emotional learning interventions. Br Edu Res J. 2015;41(3):381–97.

Mann C, Shaw AR, Guthrie B, Wye L, Man M-S, Chaplin K, et al. Can implementation failure or intervention failure explain the result of the 3D multimorbidity trial in general practice: mixed-methods process evaluation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e031438.

Hatcher AM, Bonell CP. High time to unpack the “how” and “why” of adherence interventions. AIDS (London). 2016;30(8):1301–3.

Windsor RA, Whiteside HP, Solomon LJ, Prows SL, Donatelle RJ, Cinciripini PM, et al. A process evaluation model for patient education programs for pregnant smokers. Tob Control. 2000;9(suppl 3):iii29–35.

Koutsouris G, Norwich B, Stebbing J. The significance of a process evaluation in interpreting the validity of an RCT evaluation of a complex teaching intervention: the case of Integrated Group Reading (IGR) as a targeted intervention for delayed Year 2 and 3 pupils. Camb J Educ. 2019;49(1):15–33.

Ramsay CR, Thomas RE, Croal BL, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Using the theory of planned behaviour as a process evaluation tool in randomised trials of knowledge translation strategies: a case study from UK primary care. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):71.

Parrott A, Carman JG. Scaling Up Programs: Reflections on the Importance of Process Evaluation. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation. 2019;34(1).

Zbukvic IC, Mok K, McGillivray L, Chen NA, Shand FL, Torok MH. Understanding the process of multilevel suicide prevention research trials. Eval Program Plann. 2020;82: 101850.

McIntyre SA, Francis JJ, Gould NJ, Lorencatto F. The use of theory in process evaluations conducted alongside randomized trials of implementation interventions: a systematic review. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2020;10(1):168–78.

Liu H, Muhunthan J, Hayek A, Hackett M, Laba T-L, Peiris D, et al. Examining the use of process evaluations of randomised controlled trials of complex interventions addressing chronic disease in primary health care—a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):138.

Abraham C, Johnson BT, Bruin dM, Luszczynska A. Enhancing reporting of behavior change intervention evaluations. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;66(Supplement 3):S293-S9.

Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):134–47.

Mbuya MNN, Jones A, Ntozini R, Humphery J, Moulton L, Stoltzfus R, et al. Theory-driven process evaluation of the SHINE trial using a program impact pathway approach. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(suppl 7):S752–8.

Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB. Opening the black box: using process evaluation measures to assess implementation and theory building. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(5):711.

Parker AM. Process evaluation and the development of behavioural interventions to improve psychological distress among survivors of critical illness. Thorax. 2019;74(1).

Ellard DR, Parsons S. Process evaluation: understanding how and why interventions work. In: Thorogood M, Coombes Y, editors. Evaluating health promotion: practice and methods. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Tonkin-Crine S, Anthierens S, Hood K, Yardley L, Cals JWL. Discrepancies between qualitative and quantitative evaluation of randomised controlled trial results: achieving clarity through mixed methods triangulation. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):66.

Kostamo K. Using the critical incident technique for qualitative process evaluation of interventions: The example of the “Let’s Move It” trial. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2019:232.

Rycroft-Malone J. A realist process evaluation within the Facilitating Implementation of Research Evidence (FIRE) cluster randomised controlled international trial: an exemplar. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):138.

Masterson Algar P. Advancing process evaluation research within the field of neurological rehabilitation. [dissertation on the internet]. Bangor: Prifysgol Bangor University; 2016 [cited 15 Mar 2022]. Available from: https://research.bangor.ac.uk/portal/en/theses/advancing-process-evaluation-oresearch-within-the-filed-of-neurological-rehabilitation(7f9921d6-245d-4697-8617-1cddbb43a85f).html

Legrand K, Minary L, Briançon S. Exploration of the experiences, practices and needs of health promotion professionals when evaluating their interventions and programmes. Eval Program Plann. 2018;70:67–72.

Sharma S, Adetoro OO, Vidler M, Drebit S, Payne BA, Akeju DO, et al. A process evaluation plan for assessing a complex community-based maternal health intervention in Ogun State, Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):238.

Grant A, Treweek S, Wells M. Why is so much clinical research ignored and what do we do about it? Br J Hosp Med. 2016;77(Supplement 10):554–5.

Siddiqui N, Gorard S, See BH. The importance of process evaluation for randomised control trials in education. Educational Research. 2018;60(3):357–70.

Aarestrup AK, Jørgensen TS, Due P, Krølner R. A six-step protocol to systematic process evaluation of multicomponent cluster-randomised health promoting interventions illustrated by the Boost study. Eval Program Plann. 2014;46:58–71.

May CR, Cummings A, Girling M, Bracher M, Mair FS, May CM, et al. Using normalization process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):80.

Saarijärvi M, Wallin L, Bratt E-L. Process evaluation of complex cardiovascular interventions: How to interpret the results of my trial? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;19(3):269–74.

Rotteau L, Albert M, Bhattacharyya O, Berta W, Webster F. When all else fails: The (mis) use of qualitative research in the evaluation of complex interventions. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2020.

Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Qualitative research and the gingerbread man. Health Educ J. 1995;54:389–92.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4.

Makleff S, Garduño J, Zavala RI, Valades J, Barindelli F, Cruz M, et al. Evaluating complex interventions using qualitative longitudinal research: a case study of understanding pathways to violence prevention. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(9):1724–37.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374: n2061.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

CF was funded by a PhD studentship awarded by Queen Mary University of London. This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research ARC North Thames. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CF, supervised by ST, HP, and NF, designed the critical interpretive synthesis, conducted the searches and the initial analysis. ST, HP, NF, and AD undertook double coding and contributed to the final analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

French, C., Dowrick, A., Fudge, N. et al. What do we want to get out of this? a critical interpretive synthesis of the value of process evaluations, with a practical planning framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 22, 302 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01767-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01767-7