Abstract

Background

Rapid Advice Guidelines (RAG) provide decision makers with guidance to respond to public health emergencies by developing evidence-based recommendations in a short period of time with a scientific and standardized approach. However, the experience from the development process of a RAG has so far not been systematically summarized. Therefore, our working group will take the experience of the development of the RAG for children with COVID-19 as an example to systematically explore the methodology, advantages, and challenges in the development of the RAG. We shall propose suggestions and reflections for future research, in order to provide a more detailed reference for future development of RAGs.

Result

The development of the RAG by a group of 67 researchers from 11 countries took 50 days from the official commencement of the work (January 28, 2020) to submission (March 17, 2020). A total of 21 meetings were held with a total duration of 48 h (average 2.3 h per meeting) and an average of 16.5 participants attending. Only two of the ten recommendations were fully supported by direct evidence for COVID-19, three recommendations were supported by indirect evidence only, and the proportion of COVID-19 studies among the body of evidence in the remaining five recommendations ranged between 10 and 83%. Six of the ten recommendations used COVID-19 preprints as evidence support, and up to 50% of the studies with direct evidence on COVID-19 were preprints.

Conclusions

In order to respond to public health emergencies, the development of RAG also requires a clear and transparent formulation process, usually using a large amount of indirect and non-peer-reviewed evidence to support the formation of recommendations. Strict following of the WHO RAG handbook does not only enhance the transparency and clarity of the guideline, but also can speed up the guideline development process, thereby saving time and labor costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

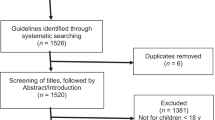

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), standard clinical practice guidelines (hereafter referred to as "standard guidelines") must be developed clearly and transparently following a rigorous methodology to obtain unbiased and high-quality recommendations and minimize the influence of conflicts of interest. The development of standard guidelines however will require on average about six months to two years to complete [1, 2]. Due to time constraints and the enormous input needed, developing standard guidelines is not the best way to assist decision-makers to rapidly make evidence-based decisions in a short period of time in case of public health emergencies. Thus, in 2006, the WHO introduced the concept and methodology of rapid advice guideline (RAG), which is characterized by short, scientific and standardized way of development. RAG aims to respond to potential public health emergencies or urgencies [3]. RAG has been proven successful with applications in several infectious diseases such as H5N1, HIV, and Ebola [4,5,6].

Since December 2019, a novel infectious disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has swept through the world, posing significant challenges to public health safety and healthcare delivery systems worldwide [7]. In such public health emergencies, guideline developers face great challenges in making urgent reasonable recommendations. Therefore, the development of a RAG is one of the effective ways to address this issue [1, 2, 8, 9]. On January 28, 2020, the development of the first international rapid advice guideline for management of children with COVID-19 (hereinafter referred to as the "RAG for children with COVID-19"), following the WHO RAG methodology and led by the National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders, was launched. RAG for children with COVID-19 was initiated by the contributions of the WHO Collaborating Center for Guideline Implementation and Knowledge Translation. It took three months from approving RAG to its publication [10, 11]. This guideline focuses on the management of children younger than 18 years infected with SARS-CoV-2, and covers screening, diagnosis, treatment, and patient education. The guideline has so far been translated into 20 languages and accepted into the Guidelines International Network library [12]. Based on the practical experience from the "RAG for children with COVID-19", the aim of this article is to summarize the methodological processes and experiences in the development of the RAG, and provides suggestions and reflections on the future development of RAGs.

Assessment of the need for the RAG

The WHO suggests to consider five factors when deciding to develop a RAG rather than standard guideline, or to delay the development of guideline. If all these five aspects are met, the development of a RAG is considered necessary. Therefore, prior to the official launch of the RAG for children with COVID-19, the core members (CMs: Liu E, Smyth RL, Chen Y, Luo Z, Li W, Zhou Q and Ren L) of the RAG working group assessed the need and rationale for the development of the RAG for children with COVID-19 based on these five aspects suggested by the WHO [1]. Having found that all five criteria were met, they concluded that it was necessary to develop a RAG for children with COVID-19 (Table 1).

Selection of development manuals

There are currently more than 60 manuals for the development of standard guidelines, including manuals issued by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), Canadian Medical Association (CMA), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), World Health Organization (WHO), American College of Physicians (ACP), and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [1, 26,27,28,29,30]. It generally takes one to two years to develop a standard guideline by following the methodology of these manuals [1, 26]. In response to public health emergencies, we need manuals that can shorten the time of guideline development. The GIN-McMaster guideline development checklist and the WHO RAG development handbook can help guideline developers complete a guideline in a short time [3, 31,32,33]. We compared the two manuals and finally chose the WHO RAG handbook for the following reasons: 1) The WHO RAG handbook has been successfully applied in the development of the RAGs of childhood tuberculosis treatment and HIV prevention and treatment in children and adolescents [34,35,36]; while GIN-McMaster has not yet been implemented in the development of RAGs; 2) We have recruited experts from WHO, who can provide us with support for the development of a RAG, and experts from WHO also recommended us to use the WHO RAG handbook; and 3) Both the WHO RAG handbook and the GIN-McMaster guideline development checklist were co-developed by experts from McMaster University, and their development processes were likely similar.

The methodology and experience from the development process

Formulation of the RAG Working Group

The RAG was initiated on January 28, 2020 by the National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders. On February 3, 2020, one of the CMs (Li W) sent invitation letters to selected experts in the relevant disciplines. Sixty-seven members from 11 countries were invited and indicated their willingness to participate in the development of the guideline. Three working groups were formed (see Additional file 1): (I) A Guideline Development Group (GDG), which comprised 39 panelists from various disciplines, including pediatricians, infectious disease physicians, pulmonologists, epidemiologists, clinical pharmacists, methodologists, nurse practitioners, health economists, general practitioners, legal experts and global health researchers. The main responsibilities of the GDG were to draft the proposal, identify clinical questions, reach consensus on the recommendations with use of a Delphi approach, and approve the final version of the guidelines; (II) A Rapid Review Group (RRG), which comprised 26 evidence synthesis methodologists and pediatricians. The primary responsibilities of the RRG were to collect clinical questions, develop rapid reviews, assess the quality of evidence, prepare recommendation decision forms and take meeting minutes; and (III) Patient Representatives (PR), which comprised of two guardians of children with COVID-19. We did not recruit children or adolescent themselves for the following reasons:1) at that time, no policy for recruitment of children with COVID-19 existed and the ethics committee of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University did not permit us to recruit children with COVID-19; 2) at the time of the development of the RAG, only few children had been diagnosed with COVID-19 and the guardians tended to be reluctant to involve their children in research [37, 38]; and 3) children, especially those under 6 years of age, are also not necessarily able to express themselves clearly enough [39]. The PRs were involved in the voting process for recommendations and providing feedback on the full text of the guideline.

Declaration and management of conflicts of interest

To ensure clarity and transparency in the development of the RAG, all participants were required to declare any potential conflicts of interest that may be relevant to the RAG [40, 41]. One CM (Li W) collected the conflicts of interest declaration forms among all members participating in the development of the RAG through email. Participants were required to declare any financial, professional and other interests that may be related to the RAG. The declared conflict of interests was reviewed by the CMs (Liu E, Chen Y, Li W, Zhou Q). Based on the assessment of conflict of interests, we limited the participation of experts with potential conflict of interests in the core work or excluded them from the overall development of the guideline. All disclosures and conflicts of interest management decisions have been publicly reported [42, 43].

Registration of the guideline and publication of the protocol

The RAG was registered on the International Practice Guidelines Registry Platform (registration No. IPGRP-2020CN008). The protocol was published on March 26 of 2020 [11].

Collection and prioritization of clinical questions

Four CMs (Liu E, Chen Y, Li W, Zhou Q) conducted a scoping review of the published literatures related to COVID-19, and developed the initial clinical questions related to children with COVID-19 [44]. After two rounds of discussions among three CMs (Liu E, Smyth RL, Li W) and clinical experts working in the frontline of infectious disease prevention, 26 clinical questions were identified for further assessment of their importance (Table 2).

On February 2, 2020, one CM (Li W) sent a clinical questionnaire to 33 GDG members by email. All experts scored each question from 1 to 7 according to its importance (1: the question is not important at all and should not be included in the guideline; 7: the question is extremely important and must be included in the guideline). Twenty-seven (81.8%) of the invited 33 GDG members completed the questionnaire. On February 7, 2020, two CMs (Li W, Zhou Q) prioritized the clinical questions according to the questionnaire scores and modified the questions based on the feedback from the GDG. After considering the score ranking and discussing the feedback, six CMs (Liu E, Smyth RL, Chen Y, Luo Z, Li W, Zhou Q) reached an agreement and included ten clinical questions (Table 2).

Evidence retrieval, assessment and synthesis

Based on the ten selected clinical questions, the RRG conducted 11 rapid reviews [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Each rapid review was assigned specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, based on the amount of available direct or indirect evidence on COVID-19 in children. In the event of sufficient available studies, we included only direct evidence from COVID-19. If there were no studies on COVID-19 in children or indirect evidence from adults, we also included indirect evidence from other coronavirus respiratory infections such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) to answer the clinical questions.

The RRG systematically searched the following databases: Cochrane library, MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, CBM (China Biology Medicine), CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) and Wanfang Data. The search terms were COVID-19, 2019-CoV, Novel coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, MERS, MERS-CoV, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS, SARS-CoV, and their synonyms, as well as terms related to specific the topic of each review. We developed the search strategy in cooperation with an experienced medical information retrieval specialist [5, 56]. The first searches were completed on 28 February 2020. Later, due to the length of the development process of the RAG, the searches were updated on March 31, 2020. In addition, the RRG also manually searched SSRN (https://www.ssrn.com/index.cfm/en/), medRxiv (https://www.medrxiv.org/) and bioRxiv (https://www.biorxiv.org/) preprint platforms and Google Scholar, and tracked references of the included studies.

Since another high-quality rapid review on the same topic was published, the rapid review on quarantine to control COVID-19 was discontinued on 8 April 2020 [45, 57]. Finally, the RRG completed 13 rapid reviews (see Additional file 2). The GRADE method was used to grade the evidence from the results of the rapid reviews [45, 58]. The detailed grading results were reported in the published articles. The questions and supporting evidence from the rapid reviews is shown in Table 3.

Formulation of recommendations

Based on the ten clinical questions and supporting evidence from rapid reviews, six CMs (Liu E, Smyth RL, Chen Y, Luo Z, Zhou Q, Li W) initially drafted ten recommendations. The relevant materials and questionnaires were sent to the GDG members by email in electronic format, and also to the two children’s guardians in paper versions. The preferences and values of the two children’s guardians and clinical experts were consistent. Two rounds of Delphi survey were conducted on February 24, 2020 and February 28, 2020, respectively, and we voted on the recommendations. The consensus criterion was that at least 70% of the invited panelists agreeing on the recommendation [45, 60]. After each round of Delphi survey, the core group discussed the feedback, revised the recommendations and also disclosed the feedback to the panel members before the next round. Detailed expert feedback can be found in Additional file 3.

A total of nine recommendations reached consensus in the first round of Delphi survey, leaving only one recommendation to be determined (Recommendation #3: CT scan should not be used routinely in the diagnosis of COVID-19 in children, although it may be helpful in monitoring children who develop severe respiratory symptoms). Six CMs (Liu E, Smyth RL, Luo Z, Chen Y, Zhou Q, Li W) revised the wording and rationale of the recommendations based on the first round of Delphi survey. Afterwards, a second round of Delphi survey was conducted for two recommendations: recommendation #3 for which consensus was not reached in the first round, and recommendation #6 (Recommendation #6: systemic glucocorticoids should not be used routinely for children with COVID-19. Only low-dose and short-duration systemic glucocorticoid therapy can be used for children with severe COVID-19 in the context of clinical trials). The recommendation was divided into two sub-recommendations (a. We recommend against using systemic glucocorticoids for children with COVID-19 routinely; b. We suggest a low dose and a short duration for severe COVID-19 children only when over inflammatory reaction or in the context of clinical trials) after feedback from the first round. Consensus were reached for both recommendations, resulting in a total of ten recommendations being finally included in the RAG. The panelists made a total of 181 comments during the two rounds of Delphi survey (Table 4).

Draft of RAG and external review

According to the Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare (RIGHT) reporting checklist, the RAG development process, clinical questions, recommendations, evidence summary and research gaps, two CMs (Zhou Q, Li W) drafted the first version of the RAG [45, 61]. Four other CMs (Liu E, Luo Z, Smyth RL, Chen Y) made secondary revisions to the content and expression. The revised version of the RAG was reviewed by four invited experts. We selected the external reviewers to ensure a balanced representation of different specialties (one external reviewer was specialized in health policy and guideline methodology, two in pediatric respiratory medicine, and one in pulmonary and critical care medicine), 2geographical regions (one reviewer from the WHO, UK, Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, China each) and genders (one female, three male). All external experts were requested to complete a conflicts of interest form, to identify any factual errors and to comment on the clarity of the language and contextual issues. Finally, the core members discussed and revised the guidelines based on the external reviewers’ comments.

In summary, the development of the RAG by a group of 67 researchers from 11 countries took 50 days from the official commencement of the work (January 28, 2020) to submission (March 17, 2020). The process took another 50 days from submission to acceptance, resulting in a total duration of 100 days (Table 5). In addition, to ensure real-time communication, the development of the RAG was intensively discussed in online meetings almost every week from February 1st to March 7th. A total of 21 meetings between the CM and the RRG were held throughout the RAG development process with a total duration of 48 h (average 2.3 h per meeting) and an average of 16.5 participants attending (Table 6).

Dissemination and implementation

We have translated this guideline into the following 20 languages: English, Chinese, Japanese, Russian, German, French, Italian, Vietnamese, Thai, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, Polish, Czech, Romanian, Burmese, Hungarian, Hebrew, Hindi, Turkish and Malay. The guideline is indexed in the International Practice Guidelines Registry Platform (IPGRP, http://www.guidelines-registry.org/news/141), the Guidelines International Network (GIN, https://g-i-n.net/get-involved/resources/), and the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI, https://guidelines.ecri.org/profile/1868) databases. In addition, we contacted the editor-in-chief in advance and discussed publication strategies to ensure a rapid publication (e.g., taking the fast track option, and fast recruitment of peer-reviewers). Considering the differences in health policies and systems, resources, feasibility and equity across the countries, through above strategies, we will assist countries and regions to adopt or adapt the guidelines into their local context.

Updating plan of the RAG

There is still a lack of effective manuals on how to update the RAG to the standard guideline. Therefore, our working group has proposed the following update plan: 1) According to the WHO guideline handbook [1], when a public health event lasts longer than six months, it should be considered to develop a standard version of the guidelines, and we therefore will update the RAG; 2) The evidence evaluation group will continuously monitor the new evidence from the field of COVID-19 (especially related to children with COVID-19), summarize the new evidence and submit the summaries to the CMs; 3) The CMs will evaluate whether potential new clinical questions should be added in the updated version and the whether the original recommendations are out of date according to the principles proposed by Shekelle et al. [62]; 4) We will invite new clinical experts and methodologists to participate in the updating of the guideline if necessary; 5) We will monitor the updating of existing RAG on COVID-19 and use their experience to guide the updating of our guideline; and 6) The updated guideline will be reported in accordance with the CheckUp checklist [63].

Challenges in the development process of the RAG

Difficulties in collecting and prioritizing clinical questions

As shown in Table 5, it took 50 days to complete the entire development process of the RAG from launch of the guideline to submission to a medical journal. This was 20 days longer than the planned schedule (one month). Two weeks of this time was spent on the identification of clinical questions (proposing clinical questions, selecting the initial clinical questions, prioritizing questions, and formatting them in PICO format).

Because COVID-19 is an emerging infectious disease that was poorly understood in children and even adults when this work was started, it was extremely challenging to select the top ten clinical questions at the beginning of the development of the RAG. First, there was a severe paucity of literature in children on COVID-19 at that time. Second, the limited number of pediatric cases were all contacts of infected adults, and the transmission routes and dynamics among the children themselves or through other sources (e.g. contaminated surfaces) were unknown. Third, the RAG development groups had no frontline clinicians with relevant clinical experience of the natural history of the disease. Fourth, as an international RAG, the clinical questions needed to be applicable to a wide and heterogeneous target population around the world.

The health systems and policies of each country need to be taken into consideration in the process of identifying clinical issues, and the importance of clinical issues vary from country to country. For example, during the survey of clinical questions, the experts proposed the question "who should be tested for nucleic acid at the beginning of an outbreak?". Health policies in some countries have been very clear on this issue (China's policy is to provide free nucleic acid testing to all persons who show clinical signs and have had close contact with a confirmed case [64]). But in most countries, only a limited number of people could be tested in the early stages of the pandemic because of the lack of nucleic acid testing kits.

Limited of direct evidence

The RAG was supported by 13 rapid reviews that incorporated evidence from studies of COVID-19, SARS and MERS. Table 3 shows only two of the ten recommendations were fully supported by direct evidence for COVID-19, three recommendations were supported by indirect evidence only, and the proportion of COVID-19 studies among the body of evidence in the remaining five recommendations ranged between 10 and 83%. Moreover, only one of the recommendations was fully supported by direct evidence from children with COVID-19, and for seven recommendations there was almost no direct evidence from children with COVID-19.

Non-peer-reviewed evidence

The RAG aims to provide instructional recommendations in the short term, and therefore studies available as preprints were used to support the evidence. Table 3 shows that six of the ten recommendations used COVID-19 preprints as evidence support, and up to 50% of the studies with direct evidence on COVID-19 were preprints. The RAG recommendations may have been influenced by the variable quality of the underpinning evidence, which may challenge the reliability of the guideline.

Rapid evolution of evidence

COVID-19 is a global pandemic and the research evidence is growing rapidly. Some of the original studies included in the rapid reviews were retracted for various reasons, resulting in the data being updated again during the production of the rapid review. For example, two studies included in the rapid review for the clinical question #4 (“Should Antiviral drugs such as ribavirin, interferon, remdesivir (GS-5734), lopinavir /ritonavir or oseltamivir be used to treat children with COVID-19?") were withdrawn, a controlled study on favipiravir was temporarily removed from Engineering on April 1 [65], and another non-randomized controlled trial of hydroxychloroquine was withdrawn from the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents on April 3rd due to not meeting the industry consensus criteria [66]. Because of the withdrawal of these studies, the rapid reviews had to be updated and revised.

Strengths in the development process of the RAG

Prospective registration and publication of the guideline protocol

The registration and publication of the protocol determines in advance the steps and methodology to be followed in developing the RAG according to the WHO handbook. Thorough development and documentation of the methodology, key issues and outcomes reduces the bias in the formulation of recommendations and minimizes the risk of inducing randomness into decision-making. In addition to the above, the registration of the guideline helps to increase the transparency of the development process, avoid duplication, enhance the credibility of the guidelines, and facilitate their dissemination and implementation.

Considering parental preferences and values

The collection and integration of parents’ preferences and values to form recommendations will help families fully understand the pros and cons of various treatment options, so that they have a stronger sense of acceptance and willingness to participate in clinical decision-making. Consideration of families’ preferences and values can thus improve patient compliance, maximize patient benefits, and improve their clinical outcomes [67]. Therefore, the RAG conducted a recommendation survey process that incorporated two guardians of children scoring our recommendations and providing relevant feedback.

Collection and prioritization of clinical questions

Clinical questions are the starting point for guideline development that determine the scope of evidence to be retrieved and evaluated at a later stage. Clinical questions also determine the content of the final recommendations [68]. Due to the urgency of the COVID-19 public health situation, solving all clinical problems at once was not possible, so we conducted a Delphi survey to rank clinical problems by a representative group of experts, and finalized 10 key clinical questions for clinicians fighting the epidemic in the frontline.

Evidence-based recommendations based on rapid review

The development of guidelines must consider the best currently available research evidence to ensure that the recommendations are comprehensive and objective. Rapid reviews can synthesize the available research evidence on the same topic in a short duration of time, and thus reduce the risk of bias and ultimately improve the reliability and accuracy of decision making. Our guideline was accompanied by 13 rapid reviews to support the development of recommendations.

Advantages of following the manual and protocol

It is well known that strict adherence to guideline development manuals and the protocol can enhance the transparency and clarity and ensure the quality and credibility of the guideline [69]. In this particular case, we did not use other standard handbooks due to time constraints. We registered a protocol, and followed the protocol and the WHO RAG manual in every step of the development process. The manual is specifically intended for rapid advice guidelines, and contains several aspects that help to carry out the development in a rapid and efficient manner. The recommendations of the WHO RAG handbook differs from the standard guideline development in the following ways:1) The method of rapid systematic review production is used instead of the traditional development process of systematic reviews in evidence synthesis, which helps to save a lot of time in document screening, evaluation and synthesis; 2) Online meetings are used instead of face-to-face meetings, which saves time, administrative workload and resources of both the organizers and the attending experts; and 3) the WHO RAG handbook requires all members of the expert group to prioritize the preparation of the guidelines, postpone other non-urgent matters, and provide efficient feedback around the rapid development of the guidelines, which guarantees a rapid turnaround time of thefeedback and response.

Conclusion

In order to respond to public health emergencies, the development of a RAG requires a clear and transparent formulation process, and usually uses a large amount of indirect and non-peer-reviewed evidence to support the formation of recommendations. Strictly following the WHO RAG handbook does not only enhance the transparency and clarity of the guideline, but also speeds up the guideline development process, thereby saving time and resources.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.

References

World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development - 2nd Edition. 2020. URL: https://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/handbook_2nd_ed.pdf?ua=1.

Norris SL. Meeting public health needs in emergencies–World Health Organization guidelines. J Evid Based Med. 2018;11:133–5. https://www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12314.

Schünemann HJ, Hill SR, Kakad M, Vist GE, Bellamy R, Stockman L, et al. Transparent development of the WHO rapid advice guidelines. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040119.

Schünemann HJ, Hill SR, Kakad M, Bellamy R, Uyeki TM, Hayden FG, et al. WHO Rapid Advice Guidelines for pharmacological management of sporadic human infection with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70684-3.

World Health Organization. Rapid Advice: use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. 2020. URL: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/advice/en/.

World Health Organization. Personal protective equipment in the context of filovirus disease outbreak response. 2020. URL: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/ppe-guideline/en/.

Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The Novel Coronavirus Originating in Wuhan, China: Challenges for Global Health Governance. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1097.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13058

Yang K, Chen Y, Li Y, Schünemann HJ, Members of the Lanzhou International Guideline Symposium. Editorial: can China master the guideline challenge? Health Res Policy and Syst. 2013;11:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-11-1.

Liu E, Smyth RL, Luo Z, Qaseem A, Mathew JL, Lu Q, et al. Rapid advice guidelines for management of children with COVID-19. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:617. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3754.

Li W, Zhou Q, Tang Y, Ren L, Yu X, Q Li, et al. Protocol for the development of a rapid advice guidelines for management of children with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:2251–5. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2020.02.33.

Guidelines International Network (GIN). COVID-19 Guidance Resources. https://g-i-n.net/covid-19/covid-19-guidance-resources.

World Health Organization. Rapid risk assessment of acute public health events. 2012. URL: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/HSE_GAR_ARO_2012_1/en/.

World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report-6. 2020. URL: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200126-sitrep-6-2019--ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=beaeee0c_4.

World Health Organization. Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. 2019. URL: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/17-07-2019-ebola-outbreak-in-the-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-declared-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern.

Lamontagne F, Fowler RA, Adhikari NK, Murthy S, Brett-Major DM, Jacobs M, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for supportive care of patients with Ebola virus disease. Lancet. 2018;391:700–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31795-6.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017.

World Health Organization. Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. 2004. URL: https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/

Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395:473–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2.

Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Du R, Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020;395:683–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30361-5.

Zhao S, Cao J, Shi Q, Wang Z, Estill J, Lu S, et al. A quality evaluation of guidelines on five different viruses causing public health emergencies of international concern. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:500. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.03.130.

The World Bank. Population ages 0–14, total. URL: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.0014.TO.

Clark H, Coll-Seck AM, Banerjee A, Peterson S, Dalglish SL, Ameratunga S, et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;395:605–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1.

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. News. 2020. URL: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/xwdt/202001/6be45fe493804bb6b96a3ed6c92ddb0f.shtml.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Graham R, Mancher M, Miller Wolman D, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, Falavigna M, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):E123-42. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131237.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). A guideline developer’s handbook. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2019. (SIGN publication no. 50). [November 2019]. Available from URL: http://www.sign.ac.uk

Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Lin JS, Mustafa RA, Wilt TJ. The Development of Clinical Guidelines and Guidance Statements by the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians: Update of Methods. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(12):863–70. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-3290.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) ; 2014. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual.pdf

Kowalski SC, Morgan RL, Falavigna M, Florez ID, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Wiercioch W, et al. Development of rapid guidelines: 1. Systematic survey of current practices and methods. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0327-8.

Florez ID, Morgan RL, Falavigna M, Kowalski SC, Zhang Y, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, et al. Development of rapid guidelines: 2. A qualitative study with WHO guideline developers. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0329-6.

Morgan RL, Florez I, Falavigna M, Kowalski S, Akl EA, Thayer KA, et al. Development of rapid guidelines: 3. GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist extension for rapid recommendations. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0330-0.

World Health Organization. Rapid advice: antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents [EB/OL]. [2020–02–20]. Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/advice/en/.

World Health Organization. Rapid advice: treatment of tuberculosis in children. URL: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44444.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents and children [EB/OL]. [2020–02–20]. Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/cryptococcal-disease/en/.

Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6): e20200702. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702.

Xu H, Liu E, Xie J, Smyth RL, Zhou Q, Zhao R, et al. A follow-up study of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 from western China. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):623. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3192.

Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Children and clinical research: ethical issues. URL: https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/wp-content/uploads/Children-and-clinical-research-full-report.pdf

World Health Organization. Declaration of interests for WHO experts-forms for submission. URL: https://www.who.int/about/declaration-of-interests/en/.

Wang X, Chen Y, Yao L, Zhou Q, Wu Q, Estill J, et al. Reporting of declarations and conflicts of interest in WHO guidelines can be further improved. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;98:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.021.

Qaseem A, Forland F, Macbeth F, Ollenschläger G, Phillips S, van der Wees P, et al. Guidelines International Network: toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:525–31. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00009.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Disclosure of interests and management of conflicts of interest in clinical guidelines and guidance statements: methods from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:354–61. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-3279.

Lv M, Luo X, Estill J, Liu Y, Ren M, Wang J, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a scoping review. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000125. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.15.2000125.

Wang Z, Zhou Q, Wang C, Shi Q, Lu S, Ma Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of children with COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):620. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3302.

Gao Y, Liu R, Zhou Q, Wang X, Huang L, Shi Q, et al. Application of telemedicine during the coronavirus disease epidemics: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):626. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3315.

Zhou Q, Gao Y, Wang X, Liu R, Du P, Wang X, et al. Nosocomial infections among patients with COVID-19, SARS and MERS: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):629. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3324.

Lv M, Wang M, Yang N, Luo X, Li W, Chen X, et al. Chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):622. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3311.

Shi Q, Zhou Q, Wang X, Liao J, Yu Y, Wang Z, et al. Potential effectiveness and safety of antiviral agents in children with coronavirus disease 2019: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):624. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3301.

Wang J, Tang Y, Ma Y, Zhou Q, Li W, Baskota M, et al. Efficacy and safety of antibiotic agents in children with COVID-19: a rapid review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):619. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3300.

Lu S, Zhou Q, Hang L, Shi Q, Zhao S, Wang Z, et al. Effectiveness and safety of glucocorticoids to treat COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):627. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3307.

Zhang J, Yang Y, Yang N, Ma Y, Zhou Q, Li W, et al. Effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin for children with severe COVID-19: a rapid review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):625. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3305.

Luo X, Lv M, Wang X, Long X, Ren M, Zhang X, et al. Supportive care for patient with respiratory diseases: an umbrella review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):621. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3298.

Yang N, Che S, Zhang J, Wang X, Tang Y, Wang J, et al. Breastfeeding of infants born to mothers with COVID-19: a rapid review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):618. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3299.

Li W, Liao J, Li Q, Baskota M, Wang X, Tang Y, et al. Public health education for parents during the outbreak of COVID-19: a rapid review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(10):628. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3312.

Li L, Tian J, Tian H, Moher D, Liang F, Jiang T, et al. Network meta-analyses could be improved by searching more sources and by involving a librarian. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1001–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.04.003.

Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD013574. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013574.

Norris SL, Meerpohl JJ, Akl EA, Schünemann HJ, Gartlehner G, Chen Y, et al. The skills and experience of GRADE methodologists can be assessed with a simple tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:150–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.07.001.

Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11(11):CD006207. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub4.

Townend GS, Bartolotta TE, Urbanowicz A, et al. Development of consensus-based guidelines for managing communication of individuals with Rett syndrome. Augment Altern Commun. 2020;36(2):71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2020.1785009.

Chen Y, Yang K, Marušić A, Qaseem A, Meerpohl JJ, Flottorp S, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the RIGHT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:128–32. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-1565.

Shekelle P, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. When should clinical guidelines be updated? BMJ. 2001;323(7305):155–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7305.155.

Vernooij RW, Alonso-Coello P, Brouwers M, Martínez García L; CheckUp Panel. Reporting Items for Updated Clinical Guidelines: Checklist for the Reporting of Updated Guidelines (CheckUp). PLoS Med. 2017;14(1):e1002207. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002207.

Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notification of the policy on financial security related to the prevention and control of COVID-19. 2020. http://www.gov.cn:8080/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-01/30/content_5473079.htm.

Cai Q, Yang M, Liu D, Chen J, Shu D, Xia J, et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: An Open-Label Control Study. Engineering (Beijing). 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007.

Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:105949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.10594.

Montori VM, Brito JP, Murad MH. The optimal practice of evidence-based medicine: incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310:2503–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281422.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:395–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012.

Chen Y, Guyatt GH, Munn Z, Florez ID, Marušić A, Norris SL, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines Registry: Toward Reducing Duplication, Improving Collaboration, and Increasing Transparency. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(5):705–7. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-7884.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amir Qaseem for giving comments to the first draft.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders (Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China) (grant number NCRCCHD-2020-EP-01); Special Fund for Key Research and Development Projects in Gansu Province in 2020; The fourth batch of “Special Project of Science and Technology for Emergency Response to COVID-19” of Chongqing Science and Technology Bureau; Special funding for prevention and control of emergency of COVID-19 from Key Laboratory of Evidence Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation of Gansu Province (grant number No. GSEBMKT- 2020YJ01); The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2020-sp14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qi Zhou (QZ), Qinyuan Li (QL), Enmei Liu (EL), Kehu Yang (KY), Zhengxiu Luo (ZL) and Yaolong Chen (YC) developed the concept of the study. Qi Zhou (QZ), Enmei Liu (EL), Kehu Yang (KY) and Yaolong Chen (YC) wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Qinyuan Li (QL), Janne Estill (JE) and Zhengxiu Luo (ZL) made critical revision. Enmei Liu (EL), Kehu Yang (KY) and Yaolong Chen (YC), Zhengxiu Luo (ZL) and Qiu Li (QL) were responsible for administration. Qi Zhou (QZ), Qinyuan Li (QL), Qi Wang (QW), Zijun Wang (ZW), Qianling Shi (QS), Jingyi Zhang (JZ), Zhou Fu (ZF), Hongmei Xu (HX), Hui Liu (HL), Yangqin Xun (YX) and Weiguo Li (WL) were responsible for data curation. Qi Zhou (QZ), Qinyuan Li (QL), Enmei Liu (EL), Qi Wang (QW), Zijun Wang (ZW), Qianling Shi (QS), Xiao Liu (XL) and Hui Liu (HL) analyzed the data. Qi Zhou (QZ), Qinyuan Li (QL), Enmei Liu (EL), Kehu Yang (KY) and Yaolong Chen (YC), Janne Estill (JE), Zhengxiu Luo (ZL), Xiaobo Zhang (XZ), Joseph L. Mathew (JLM), Rosalind L. Smyth (RLS), Detty Nurdiati (DN), and Edwin Shih-Yen Chan (ESC) developed the methodology. Janne Estill (JE), Weiguo Li (WL), Shu Yang (SY), Xixi Feng (XF), Mengshu Wang (MW), Junqiang Lei (JL), Xiaoping Luo (XL), Liqun Wu (LW), Xiaoxia Lu (XL), Myeong Soo Lee (MSL), Shunying Zhao (SZ), Edwin Shih-Yen Chan (ESYC), Yuan Qian (YQ), Wenwei Tu (WT), Xiaoyan Dong (XD), Guobao Li (GL), Ruiqiu Zhao (RZ), Zhihui He (ZH) and Siya Zhao (SZ) reviewed and edited the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and local regulations. The guideline protocol has been approved by National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders. The informed consents were obtained from all GDG members and two children's guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Q., Li, Q., Estill, J. et al. Methodology and experiences of rapid advice guideline development for children with COVID-19: responding to the COVID-19 outbreak quickly and efficiently. BMC Med Res Methodol 22, 89 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01545-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01545-5