Abstract

Background

This study sheds light on the proficiency of military medical officers who had received between 2 and 3 years of post-graduate training, in the handling of the difficult airway in a trauma manikin simulator using direct and video laryngoscopes.

Method

One hundred thirty-three doctors from the Singapore Armed Forces Medical Officer Cadet Course were assessed using high-fidelity simulator models with standardised difficult airways (simulator with tongue-swelling and cervical collar). They used the Macintosh direct laryngoscope (DL), King Vision channelled-blade laryngoscope (KVC), King Vision non-channelled blade laryngoscope (KVNC), and the McGrath (MG) laryngoscope on the same model in a randomised sequence. The intubation success rates and time to intubation were recorded and analysed for the study.

Results

The medical officers had a 71.4% intubation success rate with the DL on the difficult airway trauma simulator model and the mean time to intubation of 40.1 s. With the KVC, the success rate is 86.5% with mean intubation time of 40.4 s. The KVNC produced 24.8% success rate, with mean time to intubation of 53.2 s. The MG laryngoscope produced 85.0% success rate, with a mean time of intubation of 37.4 s.

Conclusion

Military medical officers with 2–3 years of post-graduate training had a success rate of 71.4% success rate intubating a simulated difficult airway in a trauma setting using a DL. Success rates were improved with the use of KVC and the MG laryngoscope, but was worse with the KVNC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Placement of a cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) in the trachea remains the definitive airway management when resuscitating collapsed patients and treating severely injured trauma casualties [1, 2]. Direct Laryngoscopy (DL) is the primary method for tracheal intubation, but it becomes challenging when performed under emergency trauma conditions where casualties can have possible orofacial trauma or head and neck injuries. Repeated attempts and prolonged tracheal intubation can also result in significant morbidities, and this happens more frequently when tracheal intubation via DL is attempted by inexperienced operators or junior doctors [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The advent of video laryngoscopes (VL) has markedly improved visualization of the glottis via indirect laryngoscopy, and some studies suggest that VL may improve first-pass intubation success by non-experts [9, 10].

VLs play an important role in difficult airway algorithms [11, 12]. However, recent studies have called into question the utility of VL when intubating emergency and critical patients, and some studies suggest that VLs take longer, did not improve first-pass intubation rates, and may be associated with more complications compared to DL [13,14,15,16,17].

Our study aimed to evaluate the proficiency of tracheal intubation in simulated difficult airways using SimMan® 3G manikins by military medical doctors with 2 to 3 years of postgraduate clinical experience, and the extent to which VL can improve intubation success rates and timings.

Methods

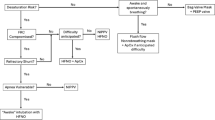

Our research was reviewed and granted approval by the institutional research committee of the Singapore Armed Forces. For the purpose of this study, the VLs selected had to be portable, battery-operated with an attached screen, relatively inexpensive, and come with disposable blades for single use appropriate for the trauma victim in an austere environment. Based on the above parameters, the research team selected the King Vision Laryngoscope and the McGrath Video Laryngoscope (MG), to be compared against the DL using a Macintosh size 3 blade in the management of simulated difficult airways (See Fig. 1). The King Vision Channeled Blade Laryngoscope (KVC) and the King Vision Non-Channeled Blade Laryngoscope (KVNC) were evaluated to investigate if channeled blade resulted in any differences in intubation success rates when used by junior medical officers with limited intubation experience.

For this study, we recruited 133 medical officer cadets of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) from 2016 to 2017. These doctors were 2 to 3 years post-graduate and would have undergone at least 3 months of anesthesia or emergency medicine department rotations. Written informed consent forms were obtained from all study participants prior to participation in the study.

A standardized simulated difficult airway scenario was created for the participants by activating the tongue-swelling feature in the SimMan® 3G manikins with a standard cervical collar applied for cervical immobilization (See Figs. 2 and 3). To simulate trauma conditions, participants had to intubate the manikins placed on a stretcher lying on flat ground with a standard size #7 ETT.

All participants were shown a training video on the use of KVC, KVNC, and MG. They also had to undergo a familiarization session with the SimMan® 3G manikins where the authors demonstrated intubations on the manikins.

Each participant was given 1 attempt for direct laryngoscopy of the SimMan® 3G manikin placed on a stretcher on the ground for which the time to intubation (TTI) was recorded. TTI was defined as time from when the participant picks up the laryngoscope to when successful tracheal intubation was confirmed by chest rise with manual ventilation via the ETT. Each participant then progressed to use the KVC, KVNC and MG following a sequence based on a 3-period, 3-treatment crossover design (see Table 1) to minimize the learning effect of successive intubations on a similar manikin. This meant that Participant #1 was given sequence A, Participant #2 was given sequence B… and Participant #6 was given Sequence F. This cycle would restart again when we reached Participant #7, would be given Sequence A.

In the event of oesophageal intubation, the participant was allowed to remove the ETT and re-attempt with no pause in the elapsed time, until either successful intubation was achieved or if 90 s had elapsed. A failed intubation was defined as failure to secure the ETT in the trachea within 90 s.

Data was collected and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Comparison of success rates was analyzed using Chi-squared tests. Analyses of continuous data (time to visualization and time to intubation) were done using paired t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 133 doctors participated in this study. All participants had at least 3 months of emergency medicine or anesthesia rotation as part of their training requirement. The median number of previous successful intubations (using either DL or VL) based on recall amongst participants was 4.

Intubation success rates for DL was 71.4% (95 out of 133) with the mean time to intubation at 40.1 + 16.6 s. For the VLs, the intubation success rates were 86.5% (115 out of 133) for the KVC, with an average time taken of 40.4 + 20.2 s. For the KVNC, intubation success rate was 24.8% (33 out of 133) with an average time of 53.2 + 28.2 s. For the MG, intubation success rate was 85.0% (113 out of 133) with an average time of 37.4 + 19.3 s. (See Tables 2 and 3).

Use of KVC and MG demonstrated higher intubation success rates for the difficult airway in a simulated trauma patient compared to DL. There was no significant difference in the time to intubation (TTI) between DL, KVC and MG when the intubation was successful. Comparing KVC with MG, we found that there was no significant difference in the intubation success rates and time to intubation (TTI).

Discussion

All Singaporean male doctors are required to undergo at least 3 months of emergency medicine or anesthesia clinical rotations in order to improve their airway management skills prior to re-enlistment as military medical officers. Given that our scenario featured simulated difficult airways in trauma patients, we concluded that airway management proficiency of these junior doctors compared favorably to other large studies which reported success rates ranging between 71.2 to 85% for emergent intubations [18,19,20].

Chew et al. did a similar study on a cohort of military medical officers and found the intubation success rates were higher with channeled King Vision and McGrath as compared to the King Vision non-channeled laryngoscope [21]. This corroborated with our study findings.

In addition, our study showed that KVC and MG VLs were superior to DL in terms of intubation success rates, but did not significantly reduce the time to intubate in successful intubations. Several other studies also compared KVC/MG to DL [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Mehmet et al. demonstrated that MG produced a better view of the glottis, but the time to successful intubation was not significantly different from the DL [25]. Piepho et al. studied 30 paramedics using DL and MG on normal and difficult airway simulators, which demonstrated that the use of MG resulted in a better view of the glottis though success rates between MG and DL were similar [27]. Interestingly, Piepho’s study participants took longer time to intubation when they used MG, compared to DL [27]. Our team hypothesized that the superiority of VL over DL became more apparent with difficult airways. On the other hand, the familiarity of DL would be more advantageous when dealing with normal (easy) airways. For difficult airway scenarios, the first attempt at intubation tends to be the best attempt. This is because repeated attempts may result in laryngeal trauma and make intubation even more difficult. Hence, our study team recommends VL (KVC and MG) to be the first line laryngoscope for intubating anticipated difficult airways, especially in out-of-hospital settings.

The channelled conduit for ETT was designed to tackle the often-criticized problem of a ‘can see, but cannot intubate’ situation when trying to pass the ETT based on indirect visualisation of vocal cords when using VL [28, 29]. Our study echoed the findings of Akihisa et al., who demonstrated higher intubation success rate for KVC at 86.6%, compared to KVNC at 47.3% [29]. The same study also demonstrated an intubation success rate of 91.4% for DL, which proved to be better than for both KVC and KVNC [29].

Despite being a non-channeled VL, the MG compared very favourably compared to KVC, the channeled variant for the KingVision Laryngoscope. It also proved superior to the KVNC in terms of intubation success rate in our study. Most junior doctors in Singapore are familiar with the use of standard Macintosh laryngoscope, which is part of the standard equipment for securing the airway. We postulated that since the MG has a similar blade curvature and shape as the Macintosh DL, the MG VL was more intuitive and thus the success rates were higher. The KVNC utilised an acute-angle blade, which allowed for easy visualisation of the manikin vocal cords whilst the manikin was positioned on the floor. However, guiding the ETT through this acute angle was a tricky manouvre that most candidates failed to achieve, which is a similar problem seen in other studies on acute angled laryngoscopes [30, 31].

Limitations

While the SimMan® 3G manikins used are high-fidelity advanced patient simulators, intubating a manikin remains different from intubating real patients. While the patient simulator can produce cervical immobilization and tongue edema, other difficult airway scenarios such as blood and secretions in the oral cavity, anatomic variations or mandibular injuries could not be simulated.

One possible bias in the study design was the ‘learning effect’ from successive intubations. With successive intubations, the study participant would be more familiar with the characteristics of the mannikin. This could possibly lead to higher success rates with subsequent intubations. Our study protocol required all participants to intubate with DL as their 1st attempt, before they were allowed to use video laryngoscopes. The ‘learning effect’ could possibly give VL an unintended advantage over DL.

Lastly, observation bias (aka Hawthorne Effect [32]) might lead to unexpectedly worse intubation success rates and timings for participants with performance anxiety, or improved intubation timings for participants who viewed this as a ‘time challenge’ and intubated much faster than they would have in real life situations.

Conclusions

A plethora of airway trials have been done over the past decade comparing various VLs when used by either novice operators or experienced laryngoscopists (emergency medicine physicians, anesthesiologists, critical care medicine physicians). We hoped this study managed to shed more light on the proficiency of airway management of medical officers fronting the first-line response to airway emergencies in the military setting.

Though not the primary objective of the study, our results suggest that the blade curvature for non-channeled VLs contributed significantly to the success or failure of intubation by novice operators. The familiarity of blade curvature could also suggest that it would be easier to train junior doctors in Singapore to be adept with MG as compared to KVNC.

Availability of data and materials

Softcopy data has been anonymized and is kept with the authors. It is available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ETT:

-

Endotracheal tube

- DL:

-

Direct laryngoscopy

- VL:

-

Video laryngoscopy

- KVC:

-

King-vision channelled blade laryngoscope

- KVNC:

-

King-vision non-channelled blade laryngoscope

- MG:

-

McGrath videolaryngoscope

- TTI:

-

Time to intubate

References

Elizabeth Sinz, Kenneth Navarro, Erik S. Soderberg, Advanced Cardiac Life Support; 2015.

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, Advanced Trauma Life Support, 10th Ed; 2018.

Jaber S, Amraoui J, Lefrant JY, Arich C, et al. Clinical practice and risk factors for immediate complications of endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: a prospective, multiple-Centre study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2355–61.

Kory P, Guevarra K, Mathew JP, et al. The impact of video laryngoscopy use during urgent endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:144–9.

Lakticova V, Koenig SJ, Narasimhan M, et al. Video laryngoscopy is associated with increased first pass success and decreased rate of esophageal intubations during urgent endotracheal intubation in a medical intensive care unit when compared to direct laryngoscopy. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:44–8.

Cook TM, Woodall N, Harper J, et al. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the difficult airway society. Part 2: intensive care and emergency departments. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:632–42.

Griesdale DE, Bosma TL, Kurth T, et al. Complications of endotracheal intubation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1835–42.

Martin LD, Mhyre JM, Shanks AM, et al. 3,423 emergency tracheal intubations at a university hospital: airway outcomes and complications. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:42–8.

Griesdale DE, Liu D, McKinney J, et al. Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012 Jan;59(1):41–52.

Silverberg MJ, Li N, Acquah SO, et al. Comparison of video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy during urgent endotracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):636–41.

Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, Blitt CD, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251–70.

Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, et al. Difficult airway society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827–48.

Jiang J, Ma D, Li B, et al. Video laryngoscopy does not improve the intubation outcomes in emergency and critical patients – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2017;21:288.

Lascarrou JB, Boisrame-Helms J, Bailly A, et al. Video laryngoscopy vs direct laryngoscopy on successful first-pass Orotracheal intubation among ICU patients. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(5):483–93.

Yeatts DJ, Dutton RP, Hu PF, et al. Effect of video laryngoscopy on trauma patient survival: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Aug;75(2):212–9.

Janz DR, Semler MW, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized trial of video laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2016 Nov;44(11):1980–7.

Platts-Mills TF, Campagne D, Chinncok B, et al. A comparison of GlideScope video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):866–71.

Saddawi-Konefka D, Baker KH, Wiener-Kronish JP. Intubation with video laryngoscopy vs direct laryngoscopy. JAMA. 2017;1:2130–1.

Wang HE, Cook LJ, Chang CC, et al. Outcomes after out-of-hospital endo-tracheal intubation errors. PubMed. 2009;80:50.

Deakin CD, Peters R, Tomlinson P, et al. Securing the prehospital airway: a comparison of laryngeal mask insertion and endotracheal intubation by UK paramedics. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:64–7.

Chew SH, Lim JZ, Chin BZB, et al. Intubation with channeled versus non-channeled video laryngoscopes in simulateddifficult airway by junior doctors in an out-of-hospital setting: a crossover manikin study. PLoSONE. 2019;14(10):e0224017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224017.

Valencia JA, Pimienta K, Cohen D, et al. A comparison of king vision video laryngoscopy and direct laryngoscopy as performed by residents: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Anaesth. 2016;1:571–5.

Jarvis JL, McClure SF, Johns D. EMS intubation improves with king vision video laryngoscopy. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2015;19:482–9.

Ali QE, Amir SH, Ahmad S. A comparative evaluation of king vision video laryngoscope (channelled). Sri Lankan J Anaesthesiol. 2017;25:70–5.

Uluer MS, Selcuk M. Comparison of McGrath® series 5 video laryngoscope with Macintosh laryngoscope: a prospective, randomised trial in patients with normal airways. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2016;1:869–74.

Ruetzler K, Imach S, Weiss M, et al. Comparison of five video laryngoscopes and conventional direct laryngoscopy : investigations on simple and simulated difficult airways on the intubation trainer. Anaesthesist. 2015;64:513–9.

Piepho T, Weinert K, Heid FM, et al. Comparison of the McGrath® series 5 and GlideScope® ranger with the Macintosh laryngoscope by paramedics. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19(1):1.

Kriege M, Alflen C, Noppens RR. Using king vision video laryngoscope with a channeled blade prolongs time for tracheal intubation in different training levels, compared to non-channeled blade. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183382.

Akihisa Y, Koyama Y, Yamada R, et al. Comparison of intubation performance between the king vision and Macintosh laryngoscopes in novice personnel: a randomized, crossover manikin study. J Anesth. 2014;28:51–7.

Itai J, Tanabe Y, Nishida T, Inagawa T, et al. Tracheal intubation for a difficult airway using airway scope®, KingVision® and McGRATH®: a comparative manikin study of inexperienced personnel. Crit Care. 2013;17:159.

Alvis BD, Hester D, Watson D, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the McGrath MAC video laryngoscope with the king vision video laryngoscope in adult patients. Minerva Anesthesiol. 2016;1:30–5.

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, et al. The Hawthorne effect: a randomized, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Lee Tat Leang, National University Hospital department of Anaesthesia, for his review of this manuscript and Ms. Liu Wei Ling for advice on the statistical analysis. The McGrath™ MAC VL used in this study are property of NUHS Anaesthesia Dept, while the King Vision® VL used was on loan from the local Ambu® authorised agent.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Siew RCH conceptualized the idea, Lim JZM conducted the trial with the assistance of Chew SH and Chin BZB. Lim JZM wrote the original draft with Chew SH and Siew RCH vetting the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Obtained from the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) Joint Medical Conference (Research) Committee. Signed informed consent was taken from participating individuals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, J.Z., Chew, S., Chin, B.Z. et al. Proficiencies of military medical officers in intubating difficult airways. BMC Emerg Med 20, 78 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00375-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00375-2