Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) and peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study based on the National Health and Nutrition Survey (1999–2004). The laboratory-calculated PNI was divided into four groups based on quartiles(Q1:PNI ≤ 50.00; Q2: 50.01–53.00; Q3:53.01–56.00; Q4: > 56.00). PAD was defined as an ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) ≤ 0.9 on the left or right. The relationship between PNI and PAD was examined using multifactor weighted logistic regression analysis, as well as subgroup analysis. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on demographic and clinical variables.

Results

A total of 5,447 individuals were included in our final analysis. The age of the participants was 59.56 ± 13.10 years, and males accounted for 52.8% (n = 2820). The prevalence of PAD was 6.7% (n = 363). After adjusting for all factors, participants with Q1 still had an increased risk of PAD, with an OR value of 1.593 and a 95% CI of 1.232–1.991. Subgroup analysis showed no significant interaction among multiple factors.

Conclusions

In summary, we report that lower PNI are associated with a higher risk of PAD in US adults. It is hoped that this discovery can provide a reference for the prevention of PAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a progressive disease characterized by the presence of atherosclerotic blockages in the peripheral vascular system, commonly affecting the arteries of the lower extremities. It often serves as a warning sign for underlying atherosclerotic disease elsewhere in the body’s blood vessels. People diagnosed with PAD are at a heightened risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular death [1]. PAD affects 3–7% of the general population and up to 20% of individuals over the age of 75 [2]. The economic burden and health risks associated with PAD cannot be overstated. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the root causes of PAD and take appropriate actions.Malnutrition is typically defined as having a low body mass index (BMI) and low serum albumin levels [3]. It is associated with a range of metabolic disorders including steatosis, increased lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation, decreased circulating amino acids, reduced peroxisome number and function, and mitochondrial dysfunction [4]. Malnutrition can also lead to immune system impairment and increased mortality from infections [5,6,7]. Acute or chronic diseases and their treatment methods can also cause malnutrition, mainly due to altered metabolism [8]. The high prevalence of diabetes-related comorbidities and complications can further undermine nutritional status, and malnutrition can result in muscle function loss, delayed wound healing, reduced bone mass, immune system dysfunction, and decreased systemic function [9, 10]. A number of scores have been developed to assess human nutritional status, including the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), the controlled nutritional status (CONUT) score, and the nutritional risk index (NRI) [11,12,13].

In this article, we postulate that there is a strong correlation between the PNI and the development of PAD. To address this hypothesis, we prospectively investigated the relationship between the PNI and PAD using a nationally representative sample of adult PAD participants in the United States.

Matieral and methods

Study population

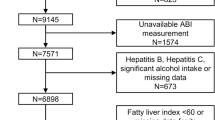

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing research project that provides estimates of the population’s nutrition and health status in the United States. This survey uses a stratified, multistage probability design to recruit a representative sample of the American population [14]. Data is gathered through structured interviews with individuals at home, health screenings at mobile health screening centers, and laboratory sample analysis. In keeping with previous studies that have investigated PAD using the NHANES database, we analyzed data from the 1999–2004 NHANES cycles (n = 31,126). A total of 7571 participants aged 40 years or older had valid ankle-brachial index (ABPI) measurements. We excluded participants who lacked information on PAD (n = 257), and those who lacked data on relevant covariates, such as BMI, lymphocyte and albumin (n = 1867) [15,16,17]. Finally, 5447 participants were included in our study (Fig. 1).

Exposure variable and outcomes

PNI was calculated by albumin count [g/l] + lymphocyte count (109)×5. The methods used to derive complete blood count (CBC) parameters are based on the Beckman Coulter method of counting and sizing, (Chap. 7 of the NHANES Laboratory), and albumin was determined by bromcresol purple, the above two indicators were measured on the same day, and the values from the first day of testing were used. ABPI was determined in subjects over the age of 40 by trained health technicians at a mobile examination center. Participants lie supine on the exam table during the exam. Systolic pressure is measured on the right arm (brachial artery) and both ankles (posterior tibial arteries). Systolic blood pressure is measured twice at each site for participants aged 40–59 years and once at each site for participants aged 60 years and older. The presence of PAD was defined as left- or right-sided ABPI ≤ 0.9 [18, 19] .

Covariates collection

Baseline characteristics of the participants were obtained through questionnaires and examinations, including sociodemographic (sex, age, ethnicity, and education) and lifestyle information (smoking status). Plasma total cholesterol, and CRP (C-reactive protein) were measured by standard biochemical methods. BMI is calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height (m) squared. Races are classified as non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Mexican Americans, other Hispanics, or others. The education level is divided into below high school, high school, equivalent education, and college. Hypertension is defined as an ASBP or ADBP of 140/90 mmHg, as currently taking blood pressure medication, or as previously diagnosed by a doctor or other health professional. Diabetes was defined as fasting blood sugar > 7 mmol/L, random blood sugar ≥ 11.1mmol/L or A1c ≥ 6.5%, or use of hypoglycemic drugs, or diagnosed with diabetes. Poverty income ratio (PIR) is an index for the ratio of family income to poverty. Smoking is defined as smoking at least 100 cigarettes in life.

Statistical analysis

Due to the complex sampling design of the NHANES database, analysis of the data required consideration of sample weights, clustering, and stratified analysis. Normally distributed data were expressed as standard deviations, while non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and analyzed using chi-square tests, while quartiles of PNI levels were identified based on the distribution of the study population. One-way ANOVA tests (for continuous variables with normal distribution), Kruskal-Wallis tests (for continuous variables with non-normal distribution), and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) were used to compare differences between the four groups. logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for cardiovascular disease mortality associated with PNI.

We also conducted several sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our findings. In stratified analyses, we divided participants based on age (≤ 60 or > 60 years), gender (male or female), smoke (yes or no), diabetes (yes or no), BMI (> 28 or ≤ 28 kg/m2), and hypertension (yes or no). We assessed the significance of the interaction by examining the P-value of the product term between the PNI level and the stratified variables. All analysis was performed by R software (version 4.1, Vienna, Austria) and spss25.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), and P < 0.05 on both sides was significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The baseline characteristics of the included participants are presented in Table 1. Significant differences were observed across each quartile of the PNI. Compared to participants with higher PNI scores (quartiles 3 and 4), those with lower PNI (quartiles 1 and 2) were more likely to be older, female, and non-smokers. These participants also had higher CRP levels and higher PIR levels. Furthermore, we observed that participants with lower PNI quartiles tended to have higher rates of PAD (Q1: 9.9%, Q2: 4.8%, Q3: 6.3%, and Q4: 5.6%, P < 0.001). Similar results were observed for the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension.

Association between PNI and PAD

Table 2 presents the results of the one-way logistic regression analysis for PAD, and it can be observed that there are statistically significant differences except for BMI and Gender. Table 3 displays the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis. When PNI was used as a quartile-based categorical variable and the fourth quartile was used as a reference, participants in the first quartile had a higher risk of PAD in all three models. After adjusting for potential confounding variables, the OR and 95% CI of the first quartile of PAD were 1.593(1.232–1.991).

We also used Spearman correlation analysis to examine the relationship between covariates linked to PNI. As shown in Table 4, PNI was negatively correlated with age and PIR (r = -0.084 and − 0.006), and positively correlated with CRP and TC (r = 0.145 and 0.139).

Stratification analysis

Stratified subgroup analysis was performed by age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, and BMI. PNI was further treated as a continuous variable. Figure 2 shows that there was a negative correlation between PNI and PAD in participants older than 60 years, without diabetes, male, female, with a BMI greater than 28 or less than 28, smokers, hypertension, without hypertension, diabetes and without diabetes. Furthermore, the link between PNI and PAD was stronger in smokers (P for interaction = 0.001).

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study, a significant positive correlation was observed between PNI and PAD prevalence, suggesting that lower PNI may lead to a high risk of PAD. We observed a sharp increase in the risk of PAD when PNI was below 50. Atherosclerosis is a systemic inflammatory disease [20]. Inflammatory markers such as NLR (Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio), PLR (Platelet-lymphocyte ratio) and CRP can be used to predict cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Rein [21] et al. reported that patients with PAD have a higher incidence of systemic inflammation than patients with coronary artery disease. PAD is not simply a peripheral atherosclerotic disease, but part of a multivascular disease [22]. Recently, the concept of a malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome has been proposed, where inflammation tends to promote a catabolic state that inhibits protein synthesis and stimulates protein degradation, leading to malnutrition and reduced GNRI [23]. Furthermore, malnutrition is a complex state that includes a decrease in protein reserves and caloric depletion, which can weaken immune defences. Reduced immune defences are a key factor in the development of many chronic diseases. Thus, there may be a positive feedback loop between inflammation, malnutrition, immune defences and adverse events, resulting in a vicious cycle [24]. PNI is a nutritional indicator that was originally developed to predict morbidity and mortality after gastrointestinal surgery [25]. Because the original PNI was complex and difficult to use routinely in clinical practice, Onodera et al. simplified its calculation method to be based on serum albumin levels and peripheral blood lymphocyte counts [26]. It is now one of the easiest routine indicators to measure. Several studies have found a significant association between PNI and atherosclerotic disease [27].

Although the significance of PNI for PAD has been reported, studies have been hampered by small sample sizes and low statistical power. Erken conducted a retrospective study that included 266 patients with peripheral arterial disease divided into an amputation group (n = 39) and a non-amputation group (n = 227). The results found that PNI was lower in the amputation group compared to the non-amputation group (31.8 vs. 39.4), and that immunonutritional status based on PNI was independently associated with amputation in patients with lower extremity PAD [13]. Itagaki included 278 patients with PAD treated with endovascular therapy with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) as an outcome at 5 years, and found that PNI was associated with a risk of MACE and possessed good prognostic predictive power [28]. Compared with the previous studies mentioned above, our study examined PNI status in a larger population cohort and revealed the relationship between high or lower PNI and the development of PAD in the population. The importance of large-scale studies cannot be overemphasized, as small studies with null results are much more likely to remain unpublished than small studies with important results, leading to publication bias.Previous retrospective studies have demonstrated that PNI can predict post-surgical clinical outcomes in patients with atherosclerotic diseases other than PAD. In a study by Balun [29], 809 patients undergoing coronary stenting for coronary artery disease were included to investigate the correlation between PNI and post-procedural all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events. The results concluded that a low PNI value indicates poor nutritional status, which was thought to accelerate the inflammatory process leading to atherosclerosis and restenosis (ISR). This is in line with our own findings. Additionally, Wada et al. reported the correlation between PNI values and long-term clinical outcomes as well as percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with stable angina [30]. A total of 1988 patients were included in the study, which found that stable angina patients with lower PNI had an increased risk of developing major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared to patients with higher PNI values. Furthermore, PNI was also significantly associated with long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stable angina. These findings suggest that PNI may be a useful predictor of cardiovascular risk in patients with stable angina.

In this study, we observed that individuals with lower PNI were more likely to be elderly or patients with a larger BMI. It is not surprising that albumin may decrease in the elderly due to insufficient nutrient intake and increased loss of nutrients. As for BMI, previous studies have confirmed that obesity may play a role in the development and progression of PAD, so it is not surprising that obesity is more common in individuals with lower PNI [31]. In addition, Spearman correlation analysis showed that participants with lower PNI levels tended to have higher age, PIR, CRP values, which may also increase PAD burden in the general population. Subgroup analyses showed that the inverse association between PNI and PAD was similar in the population. However, we found that some subgroups, including older participants and smokers, had significantly lower ORs than the corresponding subgroups. This is due to aging and smoking moderating the effect of PNI on PAD, which needs to be validated in a larger specific population in the future. Previous studies with large amounts of data point out that the prevalence of peripheral artery disease increases with age [32, 33]. As for smoking, it is a well-established risk factor for atherosclerosis worldwide [34]. However, the reduced sample size after stratification could lead to potential bias, so we need to validate this result with a larger sample size.

Despite the important findings of our study, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional study design means that causality cannot be determined. Therefore, longitudinal studies with large sample sizes are necessary to validate our results. Secondly, the lack of available ABPI data for subjects under the age of 40 limited our ability to analyze this association across various age groups. Thirdly, it is important to note that the results cannot be generalized to other populations with different demographics, as all participants were residents of the US. Lastly, the definition of PAD was based solely on ABPI measurements and was not confirmed by symptoms such as intermittent claudication, or findings from ultrasonography and angiography.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that lower PNI is associated with a higher risk of PAD in US adults. Our findings could provide valid information for large-scale prospective studies to further draw attention to nutritional status.

Data availability

The corresponding author (Yongquan Gu) will provide original data supporting the conclusions of this paper without reservation.

References

Pan D, Wang J, Guo J, et al. Impact of geriatric nutritional risk index on prognosis in peripheral artery disease patients undergoing endovascular therapy. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2023;25(5):497–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14659.

Conte MS, Pomposelli FB. Society for Vascular Surgery Practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. Introduction J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(3 Suppl):1S.

Pan D, Guo J, Su Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of atherectomy combined with balloon angioplasty vs balloon angioplasty alone in patients with femoro-popliteal lesions: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. J Endovasc Ther Published Online Dec. 2023;4. https://doi.org/10.1177/15266028231215354.

Thaxton GE, Melby PC, Manary MJ, Preidis GA. New insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of Malnutrition. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018;47(4):813–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2018.07.007.

Jones KD, Berkley JA. Severe acute malnutrition and infection. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2014;34(Suppl 1):1–S29. https://doi.org/10.1179/2046904714Z.000000000218.

Triarico S, Rinninella E, Cintoni M, et al. Impact of malnutrition on survival and infections among pediatric patients with cancer: a retrospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(3):1165–75. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_201901_17009.

Katona P, Katona-Apte J. The interaction between nutrition and infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(10):1582–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/587658.

Stratton RJ. Should food or supplements be used in the community for the treatment of disease-related malnutrition? Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(3):325–33. https://doi.org/10.1079/pns2005439.

Thomson K, Rice S, Arisa O, et al. Oral nutritional interventions in frail older people who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2022;26(51):1–112. https://doi.org/10.3310/CCQF1608.

Visser J, McLachlan MH, Maayan N, Garner P. Community-based supplementary feeding for food insecure, vulnerable and malnourished populations - an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11):CD010578. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010578.pub2. Published 2018 Nov 9.

Bouillanne O, Morineau G, Dupont C, et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index: a new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):777–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.4.777.

Shirakabe A, Hata N, Kobayashi N, et al. The prognostic impact of malnutrition in patients with severely decompensated acute heart failure, as assessed using the Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) and Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score. Heart Vessels. 2018;33(2):134–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-017-1034-z.

Erken Pamukcu H, Sunman H, Taş A, Aker M, Şahan HF, Açıkel S. The role of prognostic nutritional index in predicting amputation in patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2021;13(1):43–8. https://doi.org/10.34172/jcvtr.2021.02.

Jones MR, Apelberg BJ, Samet JM, Navas-Acien A. Smoking, menthol cigarettes, and peripheral artery disease in U.S. adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(7):1183–9.

Pan P, D, Guo J, Su Z, et al. Association of the controlling nutritional status score with all-cause mortality and cancer mortality risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: NHANES 1999–2018. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01138-2. Published 2023 Aug 21.

Liu Y, Chang L, Wu M, Xu B, Kang L. Triglyceride glucose index was Associated with the risk of Peripheral Artery Disease. Angiology. 2022;73(7):655–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/00033197211070644.

Pan D, Wang H, Wu S et al. Unveiling the Hidden Burden: Estimating All-Cause Mortality Risk in Older Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2024;2024:1741878. Published 2024 Jan 20. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/1741878.

Bozkurt AK, Tasci I, Tabak O, Gumus M, Kaplan Y. Peripheral artery disease assessed by ankle-brachial index in patients with established cardiovascular disease or at least one risk factor for atherothrombosis–CAREFUL study: a national, multi-center, cross-sectional observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-11-4.

Bergiers S, Vaes B, Degryse J. To screen or not to screen for peripheral arterial disease in subjects aged 80 and over in primary health care: a cross-sectional analysis from the BELFRAIL study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-39. Published 2011 May 23.

Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901143400207.

Rein P, Saely CH, Silbernagel G, et al. Systemic inflammation is higher in peripheral artery disease than in stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239(2):299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.021.

Yamazaki T, Goto S, Shigematsu H, et al. Prevalence, awareness and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients at high risk of atherothrombosis in Japan. Circ J. 2007;71(7):995–1003. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.71.995.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051.

Matsuo Y, Kumakura H, Kanai H, Iwasaki T, Ichikawa S. The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index predicts Long-Term Survival and Cardiovascular or Limb events in peripheral arterial disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(2):134–43. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.49767.

Chen J, Han L, Xu X, Tang H, Wang H, Wei B. Serum biomarkers VEGF-C and IL-6 are associated with severe human peripheral artery stenosis. J Inflamm (Lond). 2015;12(50). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-015-0095-y. Published 2015 Aug 18.

Stafeev I, Boldyreva M, Michurina S, et al. Grain-based dietary background impairs restoration of Blood Flow and skeletal muscle during Hindlimb Ischemia in Comparison with Low-Fat and High-Fat diets. Front Nutr. 2022;8:809732. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.809732. Published 2022 Jan 10.

Onodera T, Goseki N, Kosakim G. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients. Nihon Geka Zasshi. 1984;85:1001–5.

Itagaki T, Ebisawa S, Kato T, et al. Validation and comparison of the Prognosis Predicting ability of inflammation-based scores following endovascular treatment for peripheral artery disease [published online ahead of print, 2023 Mar 7]. Angiology. 2023;33197231161394. https://doi.org/10.1177/00033197231161394.

Balun A, Akgümüş A, Özbek K, et al. Prognostic Nutritional Index as a novel predictor of In-Stent restenosis: a retrospective study. Med (Kaunas). 2023;59(4):663. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59040663. Published 2023 Mar 27.

Wada H, Dohi T, Miyauchi K, et al. Relationship between the prognostic nutritional index and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2018;72(2):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2018.01.012.

Wolbert L, Kreutzburg T, Zyriax BC, et al. A cross-sectional survey study on the nutrition patterns of patients with peripheral artery disease. Vasa. 2022;51(4):239–46. https://doi.org/10.1024/0301-1526/a001005.

Kawamiya T, Suzuki S, Ishii H, et al. Correlations between geriatric nutritional risk index and peripheral artery disease in elderly coronary artery disease patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(7):1057–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12828.

Mine K, Sugihara M, Fujita T, et al. Impact of Controlling a Nutritional Status score on Wound Healing in patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia after Endovascular Treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):3710. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13113710. Published 2021 Oct 22.

Hicks CW, Yang C, Ndumele CE, et al. Associations of obesity with Incident Hospitalization related to Peripheral Artery Disease and critical limb ischemia in the ARIC Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(16):e008644. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008644.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2021YFC2500500). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K.; software, W.Z. and J.L.; validation, Z.X. and J.M.; formal analysis, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.Q. and D.K.; supervision, Y.Q. and J.M.; project administration, Y.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, D., Guo, J., Su, Z. et al. Association of prognostic nutritional index with peripheral artery disease in US adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 24, 133 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-03815-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-03815-0