Abstract

Background

The lifelong risks of cardiovascular disease following preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are well-established. However, it is unclear whether this evidence has been translated into clinical practice guidelines. Thus, this review aimed to assess the quality and content of Australian clinical practice guidelines regarding the risk of cardiovascular disease following gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), and CINAHL databases, as well as hospital, obstetric society, and medical college websites. Publications were included if: they were a clinical practice guideline; were published in the previous ten years; and included recommendations for the management of future cardiovascular disease risk following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Quality assessment was performed using Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Instrument Version Two (AGREE-II) and AGREE Recommendations Excellence Instrument (AGREE-REX).

Results

Eighteen guidelines were identified, and of these, less than half (n = 8) included recommendations for managing future cardiovascular risk following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Across these eight, four main counselling recommendations were found regarding (1) risk of future cardiovascular disease; (2) risk factor screening; (3) lifestyle interventions; and (4) prenatal counselling for future pregnancies. The quality and content of these recommendations varied significantly, and the majority of guidelines (87.5%) were assessed as low to moderate quality.

Conclusions

There are limited Australian clinical practice guidelines providing appropriate advice regarding future risk of cardiovascular disease following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. The quality and content of these guidelines varied significantly. These findings highlight the need for improved translation from evidence-based research to enhance clinical care and guidance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

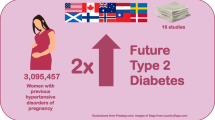

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, affect between 5% and 10% of pregnancies globally [1]. These disorders are characterised by new-onset hypertension during pregnancy, and preeclampsia is further characterised by end-organ damage. They can have devastating consequences during pregnancy for both mother and baby, including serious maternal morbidity, mortality, and stillbirth [2].

Long-term cardiovascular sequelae are also associated with preeclampsia and gestational hypertension and have been well-characterised. Following an affected pregnancy, women are at increased risk of chronic hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, and death due to cardiovascular disease, compared with their unaffected peers [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. These risks are not remote, and often manifest within a few years following pregnancy [10,11,12]. However, recent research has shown that many women are unaware of their risk [13, 14].

It is vital that women are counselled about risk mitigation either during pregnancy or early postpartum. Lifestyle interventions and regular risk factor monitoring (of blood pressure, glucose, and cholesterol) have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease among the general population, and trials are underway to validate these interventions among postpartum women [15,16,17,18,19,20,21].

The Heart Foundation Australia recommends that women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy maintain a healthy lifestyle and have regular clinical monitoring to reduce their risk of cardiovascular disease [22]. However, it is unclear whether these recommendations have been translated to obstetric practice guidelines. Women affected by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy have been reported to be more motivated to engage in sustained lifestyle modification if they are first approached during their pregnancy or early postpartum [23, 24]. Pregnancy can thus be viewed as an opportunity to engage with women and initiate positive lifestyle modifications.

Clinical practice guidelines reflect current evidence and expert recommendations for best practice and clinical care [25]. Various guidelines targeted towards obstetric care providers exist regarding the detection and management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; however, it is unclear whether they adequately address the future risk of cardiovascular disease. Australian research has demonstrated that there is a significant gap in the understanding of future risk after an affected pregnancy, not only among affected women, but also among relevant healthcare providers [26]. It has been shown that women prefer to be informed about their future risk of disease from their healthcare provider, rather than sourcing information through other channels [27]. Given this, it is critical that appropriate recommendations for managing future risk of cardiovascular disease following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are included in guidelines for healthcare providers, so that these recommendations can reach affected women.

Thus, this review aimed to assess the quality and content of current Australian clinical practice guidelines relating to the long-term management of cardiovascular disease among women affected by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Methods

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Table 1) [28]. A protocol was prospectively developed and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022328892). Ethical approval was not required as this was a review of published material.

Identification and selection of guidelines and recommendations

We included guidelines published in Australia during the preceding ten years (1 January 2012–23 May 2022) that were intended for screening, diagnosis, or management of de novo hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (Supplementary Tables 2–4). De novo hypertensive disorders of pregnancy included gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, as defined by the International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy [29]. Pre-existing hypertensive disorders (such as chronic hypertension) were not included as management of these conditions differs to that of hypertensive disorders which develop during pregnancy. Only guidelines intended for use by healthcare professionals were included. Guidelines were later excluded if they did not include recommendations pertaining to the prevention or management of future cardiovascular disease among affected women.

A search of online databases MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), and CINAHL was conducted on 23 May 2022 (Supplementary Tables 2–4). Australian government, tertiary maternity hospital, obstetric society, and medical college websites were also screened for relevant guidelines. Reference lists of included guidelines were reviewed for additional relevant materials. Only guidelines available in English were reviewed.

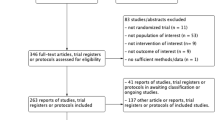

Title, abstract, and full-text screening was performed by two reviewers (JA, GS) (Fig. 1). The results of screening at each stage were compared and discrepancies were settled by screening by a third reviewer (AL). Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (JA, GS), and any discrepancies were settled by reviewer discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (AL). This process was facilitated by Covidence online software [30].

Adapted from: Page et al. (2020) [28].

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

The following fields were extracted from each included guideline: title; publishing institution; authors; year of publication; jurisdiction; population addressed; whether the guideline was adapted from previous material; and the content of specific recommendations pertaining to postpartum counselling or management of future cardiovascular disease (Tables 1 and 2).

Quality appraisal of guidelines

Quality assessment was conducted by two reviewers (JA, GS), with discrepancies settled by reviewer discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (AL). Guidelines were assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation Instrument version two (AGREE II) [31]. The AGREE II tool assesses the quality of guidelines across six domains: scope and purpose; stakeholder involvement; rigour of development; clarity of presentation; applicability; and editorial independence [31].

Quality assessment was also performed for relevant individual recommendations, which addressed postpartum cardiovascular health. Recommendations were assessed using the AGREE Recommendations Excellence Instrument (AGREE-REX) [32]. The AGREE-REX tool complements the AGREE II tool and is used to assess the quality of guideline recommendations by assessing them across three domains: clinical applicability; values and preferences; and implementability [32].

For both the AGREE II and AGREE-REX tools, guidelines are given a percentage quality score for each domain based on assessment criteria [31, 32]. For each domain, a score of < 30% was considered low quality, 30–70% moderate quality, and > 70% high quality. Quality appraisal data was visualised using the robvis risk of bias assessment figure [33].

Synthesis of guideline recommendations

Data were grouped into national, state-based, and individual hospital-based guidelines. Data regarding guideline recommendations were summarised and reported.

Results

Our search identified 2,223 papers. After removing 347 duplicates, 1,876 papers underwent title and abstract screening; 42 required full-text screening, and 18 were eligible for inclusion in the final review (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 5). Of the 18 guidelines [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], only eight (44.4%) included recommendations relating to the increased risk of cardiovascular disease following pregnancy [34, 38, 39, 41, 43, 44, 47, 49] (Table 1). For the purpose of subsequent data analysis, only these eight guidelines were considered.

Guideline characteristics

Only one national guideline was identified, published by the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) [34]. There were three included state-level guidelines (published by Queensland Health [43], Northern Territory Government/Top End Health Services [41], and South Australia Health [47]). Only four hospitals had relevant, publicly available guidelines (Monash Health, Victoria [39]; The Royal Women’s Hospital, Victoria [49]; Liverpool Hospital New South Wales [38]; and The Royal Hospital for Women, New South Wales [44]).

Four guidelines were stated to be based on previously published material: the Northern Territory guideline [41] was adapted from a previous version of the Queensland guideline [43]; the Liverpool Hospital guideline [38] was based on a 2011 New South Wales state guideline [51]; South Australia [47] and Monash Health [39] were both adapted from the SOMANZ guideline [34].

Recommendations for postpartum management

Counselling about increased risk of chronic disease

Monash Health [39], South Australia [47], Liverpool Hospital [38], and the Royal Hospital for Women (New South Wales [NSW]) [44] recommend that clinicians counsel women about their increased risk of cardiovascular disease. The Royal Hospital for Women (NSW) [44] included the greatest detail for clinicians, stating that, “women who have had preeclampsia or gestational hypertension are at higher risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism later in life,” (page 9) and recommending that clinicians, “advise women regarding long-term health implications,” (page 7). Monash Health [39] stated that clinicians should counsel women about, “hypertension and cardiovascular disease risks later in life,” (page 12) and South Australia [47] stated that women are, “at increased risk of cardiovascular disease,” (page 6), whilst Liverpool Hospital [38] only noted that women are at, “increased risk of future chronic hypertension,” (page 6) (Table 2).

SOMANZ [34], Queensland [43], Northern Territory [41], and South Australia [47] also referred to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. None of the hospital-based guidelines included reference to future diabetes risk.

Lifestyle modification

SOMANZ [34], Queensland [43], Northern Territory [41], South Australia [47], and Monash Health [39] included recommendations for lifestyle modification to reduce future risk of cardiovascular disease. SOMANZ [34] recommended, “counselling women [to consider] avoiding smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and eating a healthy diet,” (page 33). Queensland [43], Northern Territory [41], South Australia [47], and Monash Health [39] included near-identical recommendations. Queensland [43] and Northern Territory [41] additionally advise that clinicians should, “encourage overweight and obese women to attain a healthy [body mass index] for long term health,” (page 28 and 24, respectively) (Table 2).

Risk factor screening

All guidelines except for Monash Health [39] recommended risk factor screening post-pregnancy. These generally include annual blood pressure monitoring (recommended by SOMANZ [34], Queensland [43], Northern Territory [41], South Australia [47], and Royal Hospital for Women [NSW] [44]). The Royal Women’s Hospital (Victoria) [49] and Liverpool Hospital [38] also recommend blood pressure monitoring, but do not state how often this should occur.

Other recommended screening tests include regular (at least every five years) monitoring of blood glucose and serum lipids (recommended by SOMANZ [34] and South Australia [47]). Northern Territory [41] and Queensland [43] also recommend monitoring serum lipids and blood glucose, but do not state how often this should be performed. Liverpool Hospital [38] additionally recommends renal follow-up. The Royal Hospital for Women (NSW) [44] simply states that, “assessment for cardiovascular risks,” (page 7) should be performed (Table 2).

Prenatal counselling and prophylaxis for future pregnancies

Counselling about risk of disease recurrence in future pregnancies is recommended by Northern Territory [41], Queensland [43], Liverpool Hospital [38], Monash Health [39], and Royal Hospital for Women (NSW) [44]. SOMANZ [34] also recommends pre-pregnancy counselling for future pregnancies if risk is considered “significant” (page 30). Prophylaxis to prevent disease recurrence in future pregnancies (e.g., low-dose aspirin) is recommended by SOMANZ [34], Northern Territory [41], Queensland [43], and Royal Hospital for Women (NSW) [44].

Risk of bias assessment

The AGREE II tool revealed mixed results regarding guideline quality (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 6) National and state-based guidelines were generally considered of higher quality than hospital-based guidelines. The Queensland [43] guideline was assessed to have the lowest overall risk of bias. Major risks of bias were introduced in the editorial independence and applicability domains, highlighting the difficulty that may be faced in implementing these guidelines across the country.

Adapted from McGuinness & Higgins (2020) [33]

AGREE II (A) and AGREE REX (B) robvis risk of bias assessment.

Assessing recommendations via AGREE-REX also revealed mixed results, with values and preferences being the most poorly reported domain (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 7). SOMANZ [34] was found to have the most consistently high-quality recommendations.

Discussion

Cardiovascular disease represents a significant risk to women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Timely counselling from their healthcare team is vital to ensure women are made aware of this risk and the early steps they can take to mitigate it. Despite this, we found that among eighteen obstetric clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, less than half included recommendations to counsel women on their future risk of cardiovascular disease.

We considered four main aspects that should be communicated to affected women by their healthcare team, in accordance with advice from The Heart Foundation Australia [22]. These were: their increased risk of cardiovascular disease; the benefits of lifestyle intervention; the importance of regular risk factor assessment; and the risk of recurrence in future pregnancies (and associated risk-reduction strategies) [22].

We found that obstetric guidelines varied significantly in the content of their postpartum recommendations. Whilst the majority suggested that affected women should have regular risk factor screening (7/8), consensus about timing of this screening was lacking. Recommendations for prenatal counselling were also common (6/8), and some guidelines also noted the benefit of prophylaxis in future pregnancies. However, only five guidelines recommended lifestyle modification, and only four specifically recommended counselling women on their increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

We also noted significant variation in the quality of guidelines and their recommendations. We note that a significant limitation of the recommendations for management of cardiovascular disease risk was a lack of a substantial evidence base. Whilst trials are underway, existing literature does not provide clear consensus on the optimal timing of follow-up for women affected by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, which we saw reflected in the practice recommendations [52,53,54]. However, the benefits of early counselling with women about lifestyle interventions and risk factor screening have become increasingly apparent, particularly in recent years [23, 24].

The current guidelines may benefit from an updated review of literature, as we note that, whilst two guidelines were published in 2021–2022 (Monash Health [39] and Queensland [43]), the majority are now at least three years old. The SOMANZ guideline [34] is now almost a decade old (published in 2014), and, given that this is the national resource and informs many of the other guidelines, it is important that this is updated to reflect the most recent evidence. We note that SOMANZ has indicated their intention to publish an updated guideline in 2023.

Guidelines generally lacked advice about tailoring their recommendations to specific groups (as assessed in AGREE REX Item 9 – Local Application and Adoption). In the Australian context, we note the lack of specific guidance around long-term management of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Zhao et al. (2022) highlighted the disparity in cardiovascular disease burden between First Nations and non-First Nations women in the Northern Territory, with cardiovascular disease accounting for 142.5/100,000 deaths among First Nations women and only 52.9/100,000 deaths among non-First Nations women [55]. Tailoring advice to specific groups has been proven to be an effective method to promote health behaviour change [56]. Rather than using a single set of recommendations for all Australian women, it may be beneficial to consider the use of specific recommendations to reach more vulnerable cohorts.

Whilst this review focused on content, it is also important to note the necessity of appropriate dissemination of these guidelines. A 2013 German study demonstrated that, while most clinicians were aware of the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future chronic disease, less than half were familiar with national guidelines [57]. If they were familiar with guidelines, clinicians were more likely to follow the recommended actions, such as counselling affected women [57]. These findings highlight not only the importance of appropriate practice recommendations, but also the direct dissemination of guidelines to clinicians, to ensure that guidance benefits the affected patient group. Further research into appropriate guideline dissemination in the Australian context may be warranted.

The period between a pregnancy affected by preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and the onset of cardiovascular disease provides a unique opportunity for monitoring and intervention, but only if this time is effectively utilised. Globally, obstetric guidelines are starting to recognise the importance of counselling women about their increased risk of cardiovascular disease [58, 59], and yet, less than half of Australian guidelines have followed suit. Unsurprisingly, a recent Australian survey reported that only two-thirds of practitioners discuss lifestyle adjustments with women affected by hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and evidence has shown that many women are unaware of their increased risk of cardiovascular disease, nor do they routinely receive appropriate follow-up [14, 60].

We note that many postpartum recommendations for women are based on general, population-wide recommendations to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease. These recommendations are typically based on research conducted in older, male, or non-pregnant populations. Evidence to suggest the optimal strategy to manage cardiovascular disease risk in the postpartum population is lacking [18, 19, 61]. However, the current recommendations are broadly effective in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population, and are therefore useful, given the lack of specific evidence tailored towards postpartum women [15,16,17]. It is important that targeted research into risk management among women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy be conducted to further enhance our evidence-based guidelines.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this review is the first to explore the quality and content of published Australian clinical practice guidelines relating to cardiovascular disease following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. This review supports the development of more uniform, robust, and evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to direct the management of long-term cardiovascular disease risk for affected women.

Our review was limited by access to publicly available guidelines only, although this is a universal limitation of systematic reviews and is not unique to this study. The guidelines included were found to be of varying quality, and many guidelines were based on secondary evidence from other guidelines. This made comparison and quality assessment more difficult, however, this limitation was accounted for in the data extraction process.

Conclusion

The postpartum cardiovascular sequelae following hypertensive disorders of pregnancy has been well-characterised and contributes to a significant burden of disease for affected women. Among Australian clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, only eight (44%) provided recommendations to counsel women on managing this risk, and, among these, there was considerable variation in quality and content. This review highlights the need for the development of more robust, consistent, and evidence-based guidelines to manage the risk of cardiovascular disease following preeclampsia or gestational hypertension.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Fox R, Kitt J, Leeson P, Aye CYL, Lewandowski AJ. Preeclampsia: risk factors, diagnosis, management, and the Cardiovascular impact on the offspring. J Clin Med 2019, 8(10).

Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B. Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/eclampsia. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(1):56–9.

Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CS, Babu A, Kotronias RA, Rushton C, Zaman A, Fryer AA, Kadam U, Chew-Graham CA et al. Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Health: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017, 10(2).

Brouwers L, van der Meiden-van Roest AJ, Savelkoul C, Vogelvang TE, Lely AT, Franx A, van Rijn BB. Recurrence of pre-eclampsia and the risk of future hypertension and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1642–54.

Benschop L, Brouwers L, Zoet GA, Meun C, Boersma E, Budde RPJ, Fauser BCJM, Groot CMJd, Schouw YTvd, Maas AHEM, et al. Early Onset of Coronary Artery Calcification in Women with previous Preeclampsia. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(11):e010340.

Lo CCW, Lo ACQ, Leow SH, Fisher G, Corker B, Batho O, Morris B, Chowaniec M, Vladutiu CJ, Fraser A, et al. Future Cardiovascular Disease Risk for Women with gestational hypertension: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(13):e013991.

Melchiorre K, Thilaganathan B, Giorgione V, Ridder A, Memmo A, Khalil A. Hypertensive Disorders of pregnancy and future Cardiovascular Health. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:59.

Veiga ECA, Rocha PRH, Caviola LL, Cardoso VC, Costa FDS, Saraiva M, Barbieri MA, Bettiol H, Cavalli RC. Previous preeclampsia and its association with the future development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin (Sao Paulo) 2021, 76e1999.

Arnott C, Nelson M, Alfaro Ramirez M, Hyett J, Gale M, Henry A, Celermajer DS, Taylor L, Woodward M. Maternal cardiovascular risk after hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Heart. 2020;106(24):1927–33.

Engeland A, Bjørge T, Klungsøyr K, Skjærven R, Skurtveit S, Furu K. Preeclampsia in pregnancy and later use of antihypertensive drugs. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(6):501–8.

Veerbeek JHW, Hermes W, Breimer AY, Rijn BBv, Koenen SV, Mol BW, Franx A, Groot, CJMd. Koster MPH: Cardiovascular Disease risk factors after Early-Onset Preeclampsia, Late-Onset Preeclampsia, and Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65(3):600–6.

Behrens I, Basit S, Melbye M, Lykke JA, Wohlfahrt J, Bundgaard H, Thilaganathan B, Boyd HA. Risk of post-pregnancy hypertension in women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3078.

Roth H, LeMarquand G, Henry A, Homer C. Assessing knowledge gaps of women and Healthcare Providers concerning Cardiovascular Risk after Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy-A scoping review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:178.

Atkinson J, Wei W, Potenza S, Simpson G, Middleton A, Walker S, Tong S, Hastie R, Lindquist A. Patients’ understanding of long-term cardiovascular risks and associated health-seeking behaviours after pre-eclampsia. Open Heart. 2023;10(1):e002230.

Pinckard K, Baskin KK, Stanford KI. Effects of Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:69.

Yu E, Malik VS, Hu FB. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention by Diet modification: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):914–26.

Banks E, Joshy G, Korda RJ, Stavreski B, Soga K, Egger S, Day C, Clarke NE, Lewington S, Lopez AD. Tobacco smoking and risk of 36 cardiovascular disease subtypes: fatal and non-fatal outcomes in a large prospective australian study. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):128.

Berks D, Hoedjes M, Raat H, Duvekot JJ, Steegers EA, Habbema JD. Risk of cardiovascular disease after pre-eclampsia and the effect of lifestyle interventions: a literature-based study. BJOG. 2013;120(8):924–31.

Lui NA, Jeyaram G, Henry A. Postpartum interventions to Reduce Long-Term Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Women after Hypertensive Disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:160.

Davis GK, Roberts L, Mangos G, Henry A, Pettit F, O’Sullivan A, Homer CS, Craig M, Harvey SB, Brown MA. Postpartum physiology, psychology and paediatric follow up study (P4 Study) - study protocol. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016;6(4):374–9.

Henry A, Arnott C, Makris A, Davis G, Hennessy A, Beech A, Pettit F, Se Homer C, Craig ME, Roberts L, et al. Blood pressure postpartum (BP(2)) RCT protocol: follow-up and lifestyle behaviour change strategies in the first 12 months after hypertensive pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020;22:1–6.

Pregnancy and heart. disease: Information and resources for health professionals [https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/conditions/fp-pregnancy-and-heart-disease].

Sandsæter HL, Horn J, Rich-Edwards JW, Haugdahl HS. Preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and later risk of cardiovascular disease: women’s experiences and motivation for lifestyle changes explored in focus group interviews. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):448.

Roth H, Henry A, Roberts L, Hanley L, Homer C. Exploring education preferences of australian women regarding long-term health after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a qualitative perspective. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21.

Brignardello-Petersen R, Carrasco-Labra A, Guyatt GH. How to interpret and use a clinical Practice Guideline or recommendation: users’ Guides to the Medical Literature. JAMA. 2021;326(15):1516–23.

Roth H, Homer CSE, Arnott C, Roberts L, Brown M, Henry A. Assessing knowledge of healthcare providers concerning cardiovascular risk after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: an australian national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):717.

Roth H, Homer CSE, LeMarquand G, Roberts LM, Hanley L, Brown M, Henry A. Assessing australian women’s knowledge and knowledge preferences about long-term health after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a survey study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042920.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, Gupte S, Hennessy A, Karumanchi SA, Kenny LC, McCarthy F, Myers J, Poon LC, et al. The 2021 International Society for the study of hypertension in pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;27:148–69.

Covidence systematic review software. In. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation.

Brouwers MKM, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna S, Littlejohns P, Makarski J. Zitzelsberger L for the AGREE Next steps Consortium.: AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 2010.

Florez ID, Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Alonso-Coello P, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Férvers B, Graham I, Grimshaw J, Hanna S, Kastner M, Kho M, Qaseem A, Straus S. Assessment of the quality of recommendations from 161 clinical practice guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and evaluation–recommendations Excellence (AGREE-REX) instrument shows there is room for improvement. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):79.

McGuinness L, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Syn Meth 2020, 1–7.

Lowe SABL, Lust K, McMahon LP, Morton M, North RA, Paech M, Said JM. Guideline for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ); 2014.

Canberra Hospital and Health Services Clinical Guideline Hypertension in Pregnancy. Canberra Hospital and Health Services/ACT Government; 2017.

Hypertension in pregnancy: Midwifery care. Government of Western Australia. North Metropolitan Health Service. Women and Newborn Health Service. King Edward Memorial Hospital; 2018.

Hypertension in pregnancy: Medical management. Government of Western Australia. North Metropolitan Health Service. Women and Newborn Health Service. King Edward Memorial Hospital; 2020.

Hypertension in Pregnancy. Liverpool Hospital; 2018.

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: pre-eclampsia/eclampsia. Monash Health; 2022.

Hypertension in Pregnancy (Pre-Eclampsia & Eclampsia). Peninsula Health; 2019.

Powell V. Hypertensive Disorders in pregnancy TEHS Maternity Guideline. Northern Territory Government/Top End Health Services; 2019.

Clinical Practice Guidelines: Obstetrics/Pre-Eclampsia. Queensland Ambulance Service; 2016.

Hypertension and Pregnancy. Queensland Health; 2021.

Hypertension: Management in pregnancy. Royal Hospital for Women; 2020.

Pre-eclampsia - Intrapartum Care. Royal Hospital for Women; 2020.

Severe and/or urgent hypertension in pregnancy. Royal Hospital for Women; 2020.

Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. South Australia Health; 2020.

Hypertension in Pregnancy. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne; 2021.

Pre-Eclampsia Management. The Royal Women’s Hospital; 2020.

Hypertension - Management of Acute. The Royal Women’s Hospital; 2020.

Maternity - Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. NSW Government. 2011.

Jääskeläinen T, Kivelä A, Renlund M, Heinonen S, Aittasalo M, Laivuori H, Sarkola T. Protocol: a randomized controlled trial to assess effectiveness of a 12-month lifestyle intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in families ten years after pre-eclampsia (FINNCARE). Prev Med Rep. 2022;26:101731.

Taylor R, Shrewsbury VA, Vincze L, Campbell L, Callister R, Park F, Schumacher T, Collins C, Hutchesson M. Be Healthe for your heart: protocol for a pilot randomized controlled Trial evaluating a web-based behavioral intervention to improve the Cardiovascular Health of Women with a history of Preeclampsia. Front Cardiovasc Med 2019, 6.

Jowell AR, Sarma AA, Gulati M, Michos ED, Vaught AJ, Natarajan P, Powe CE, Honigberg MC. Interventions to Mitigate Risk of Cardiovascular Disease after adverse pregnancy outcomes: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(3):346–55.

Zhao Y, Li SQ, Wilson T, Burgess CP. Improved life expectancy for indigenous and non-indigenous people in the Northern Territory, 1999–2018: overall and by underlying cause of death. Med J Aust. 2022;217(1):30–5.

Bol N, Smit ES, Lustria MLA. Tailored health communication: Opportunities and challenges in the digital era. Digit Health. 2020;6:2055207620958913.

Heidrich M-B, Wenzel D, von Kaisenberg CS, Schippert C, von Versen-Höynck FM. Preeclampsia and long-term risk of cardiovascular disease: what do obstetrician-gynecologists know? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):61.

Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(6):e237–60.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. In: Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management edn. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Copyright © NICE 2019.; 2019.

Hutchesson M, Shrewsbury V, Park F, Callister R, Collins C. Are women with a recent diagnosis of pre-eclampsia aware of their cardiovascular disease risk? A cross-sectional survey. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;58(6):E27–e28.

Timpka S, Stuart JJ, Tanz LJ, Rimm EB, Franks PW, Rich-Edwards JW. Lifestyle in progression from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to chronic hypertension in nurses’ Health Study II: observational cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3024.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

AL (No. 1185467), ST (No. 1136418), and RH (No. 1176922) receive salary support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AL and RH conceived of and designed this review. GS and JA completed the systematic review of the literature, data extraction, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors approve the submitted version of the manuscript and agree to be personally accountable for their own contributions and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Table 1

. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Supplementary Table 2. OVID Medline database search strategy. Supplementary Table 3. EMBASE database search strategy. Supplementary Table 4. CINAHL database search strategy. Supplementary Table 5. Characteristics of included and excluded guidelines. Supplementary Table 6. Quality assessment - AGREE II instrument. Supplementary Table 7. Quality assessment - AGREE-REX instrument.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Atkinson, J., Simpson, G., Walker, S.P. et al. The long-term risk of cardiovascular disease among women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23, 443 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03446-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03446-x