Abstract

Background

While understanding the impact of mental health on health perception improves patient-centered care, this relationship is not well-established in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD). We examined the relationship between psychological distress and health perception in patients with a previous myocardial infarction (MI) and/or stroke.

Methods

We extracted data for patients with a previous MI and/or stroke from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Health perception was self-reported. Presence and severity of anxiety and depression were estimated using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8). Binary analyses of anxiety/depression, multivariable logistic regressions controlling for confounders, and univariable analyses of confounders and anxiety/depression severity were performed.

Results

Of 31,948 individuals for whom data on MI/stroke was available, 1235 reported a previous MI and 1203 a previous stroke. The odds of positive perceived health status were lower for individuals with anxiety/depression compared to those without anxiety/depression in both post-MI (anxiety OR 0.52, 95% CI = 0.32–0.85, P < 0.001; depression OR 0.45, 95% CI = 0.29–0.7, P < 0.001) and post-stroke groups (anxiety OR 0.61, 95% CI = 0.39–0.97, P < 0.001; depression OR 0.37, 95% CI = 0.25–0.55, P < 0.001) upon multivariable analyses. Increasing severity of anxiety/depression was also associated with worse perception of health status upon univariable analysis.

Conclusion

Among patients with a previous acute CVD event, those with psychological distress have worse perception of their health status. Understanding the range of patient health perceptions can help physicians provide more patient-centered care and encourage patient behaviors that may improve both CVD and mental health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are leading causes of mortality in the US, and the relationship between CVD events, defined as myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, with anxiety and depression is at the forefront of discussions about mental health in cardiovascular medicine [1,2,3]. Surviving an MI or stroke can lead to a long road to recovery for patients, which may be even more arduous when a survivor suffers from anxiety or depression [7, 8]. This is especially relevant given increased rates of anxiety and depression and increased incidence of coronary artery disease observed with the COVID-19 pandemic [9,10,11].

However, little is known about the factors related to how patients represent their own illness experiences in CVD event survivors [4,5,6]. According to Leventhal’s common sense model, illness perceptions can influence how patients cope with illness – a patient’s level of self-esteem and agency to perform protective health behaviors could directly affect outcomes [12]. For example, a systematic review found increased attendance to cardiac rehabilitation in MI survivors who view their illness as controllable [13].

Little is known on the relationship between illness perception and anxiety or depression in CVD event survivors, so we used nationally representative data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to highlight factors related to health perception in patients with a previous CVD event. We examined the relationship between the presence and severity of anxiety and depression with health perception in these populations.

Methods

Data source and sample

We analyzed data from the 2019 NHIS Sample Adult Interview, a nationally representative dataset of US adults [14]. The survey is published annually by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention; methods have previously been published [14]. In short, the cross-sectional household interview survey of non-institutionalized US civilians is conducted annually in a face-to-face format.

In 2019, the survey was redesigned to collect data on self-health perception, anxiety, and depression using validated screening tools: the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8). These were in addition to the continued collection of demographic data [15,16,17].

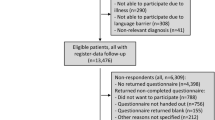

In 2019, 31,997 adults completed the survey, with a response rate of 59.1%. We included participants with a response of “yes” to having ever been told by a healthcare professional that they had an MI/stroke (n = 2,436).

Measures

Health perception and psychological distress

Health perception was assessed by the question: “Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Anxiety and depression presence and severity were estimated using GAD-7 and PHQ-8 according to NHIS severity cutoffs: none/minimal (values 0–4), mild (values 5–9), moderate (values 10–14), and severe (values > 14) [15,16,17]. Presence of anxiety and depression were defined by a GAD-7 or PHQ-8 score greater than 4, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Subjects without a response for health perception, anxiety, depression, MI, or stroke were excluded. Anxiety and depression prevalence were reported as a percentage of respondents. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the relationships between anxiety or depression and negative or positively perceived health status (NPHS or PPHS) defined as having answered “good”, “very good”, or “excellent” to the health perception survey question. Univariable analyses evaluated the association of anxiety/depression severity and other variables, including age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, household income, insurance status, and number of other comorbidities, with PPHS, separately for patients with prior MI and stroke. Then, multivariable models of the relationship between depression/anxiety and PPHS were constructed that adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, BMI, household income, insurance status, and number of comorbidities.

All analyses were performed using Stata BE [18]. NHIS sampling weights were applied to provide nationally representative estimates and standard errors accounting for the complex sample design. We denote statistical significance with the following symbol: “*”.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of those with a previous MI (n = 1235, sample-weighted estimate, 7,864,416), approximately 48.1% reported having PPHS. Of those with a previous stroke (n = 1203, sample-weighted estimate, 7,741,516), 44.8% reported PPHS. Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of respondents.

Health perception in MI-survivors

Of the 1195 (sample weighted estimate = 7,591,061) post-MI adults with GAD-7 responses, 23.2% reported anxiety and of the 1200 (sample weighted estimate = 7,627,702) with PHQ-8 responses, 33.9% reported depression (Table 1). Univariable logistic regression analyses, with reference groups of none/minimal anxiety or depression, showed that mild [OR 0.36 (0.21, 0.59), p < 0.001*], moderate [OR 0.15 (0.06, 0.34), p < 0.001*], and severe anxiety [OR 0.13 (0.06,0.13), p < 0.001*], and mild [OR 0.31 (0.21, 0.47), p < 0.001*], moderate [OR 0.19 (0.10, 0.36), p < 0.001*], and severe depression [OR 0.09 (0.04, 0.18), p < 0.001*] were associated with NPHS (Table 3). A multivariable model confirmed that the presence of either anxiety or depression were associated with decreased odds of PPHS, but there were mixed results related to anxiety/depression severity (Table 4). In our multivariable models, the odds of self-reporting PPHS was 48% lower among those with anxiety [OR 0.52 (0.32, 0.85), p < 0.009*], and 55% lower among those with depression [OR 0.45 (0.29, 0.70), p < 0.001*] compared to those who did not report a mental health comorbidity (Table 4).

Post-stroke health perception

Of the 1157 (sample weighted estimate = 7,386,687) post-stroke patients with GAD-7 responses, 28.9% reported anxiety, and of the 1162 (sample weighted estimate = 7,432,345) with PHQ-8 responses, 40.4% reported depression. Similarly to post-MI patients, those with mild [OR 0.39 (0.23, 0.63), p < 0.001*], moderate [OR 0.17 (0.08, 0.35), p < 0.001*], and severe [OR 0.14 (0.07, 0.28), p < 0.001*] anxiety, and mild [OR 0.32 (0.22, 0.46), p < 0.001*], moderate [OR 0.18 (0.10, 0.32), p < 0.001*], and severe [OR 0.12 (0.06, 0.24), p < 0.001*] depression demonstrated a negative association between anxiety/depression and PPHS compared to subjects with none/minimal anxiety or depression (Table 5). Multivariable analysis revealed that the odds of reporting PPHS was 39% lower among those with anxiety [OR 0.61 (0.39, 0.97), p < 0.037*] and 63% lower among those with depression [OR 0.37 (0.25, 0.55), p < 0.001*] compared those without anxiety or depression, respectively; there were mixed results related to the severity of anxiety and depression (Table 4).

Other factors related to health perception

Minority groups were more likely to report NPHS in a univariable analysis. Among self-identified Non-Hispanic (NH) Black/African American (AA) individuals, the odds of reporting PPHS was 52% lower among post-MI participants [OR 0.48 (0.30, 0.76), p < 0.002*] and 33% lower among post-stroke participants [OR 0.67 (0.67, 0.97, p < 0.034*] compared to self-identified NH White individuals (Tables 3 and 5). Tables 3 and 5 further describe factors that may be related to health status perception in univariable analyses.

Discussion

Our analysis demonstrates that anxiety and depression are significantly associated with NPHS in a large, nationally representative sample of US adults with a previous MI/stroke. Additionally, subjects with higher severity of anxiety and depression may be more likely to have NPHS in our sample. By demonstrating the relationship between mental illness and illness perception in survivors of different CVD events, we hope that this study encourages providers to address health perception and mental illness, and informs the development of interventions to improve mental health and behavior change in CVD event survivors.

Relationship between CVD events and psychological distress

While Leventhal’s common sense theory suggests the limitation of patient behavior change and action in accordance with their treatment plan when overcome by fear or lack of the feeling that their actions can change their outcomes, the evidence on interventions to affect health perception and behavior change, and factors that may be related to health perception is currently limited [12].

We know that psychological distress in post-MI patients has been associated with poorer health outcomes and higher rates of anginal symptoms at one year post-MI [19]. One additionally found that self-perception of high stress in a patient’s life correlates with high levels of psychological distress and increases the risk of premature death [20].

Prior to our study, it was unknown whether psychological distress and health perception in MI survivors were related. In our study, those with NPHS were more likely to have anxiety/depression: 65.2% of post-MI patients with NPHS reported none/minimal anxiety, while 89% of post-MI patients with PPHS reporting none/minimal anxiety. Similarly, 50.8% of post-MI patients with NPHS reported none/minimal depression, compared to 82.3% of post-MI patients with PPHS and none/minimal depression.

It is also well known that depressed mood can affect stroke survivors [21, 22]. Poor social support and psychological distress increase depressive symptoms in post-stroke patients [23]. Anxiety is also common following a stroke, especially in the first year [24]. Among post-stroke patients in our study, 59.3% with NPHS and 85.2% with PPHS reported none/minimal anxiety, while 44.4% of those with NPHS and 78% with PPHS who reported none/minimal depression. Additionally, in this study, increased severity of anxiety/depression correlated with worse perceived health status in post-MI and post-stroke groups.

Acknowledging that a relationship exists between mental health and illness perception can inform the design of future interventions to improve post-MI and post-stroke care. While we are unable to assess temporality due to the cross-sectional design of this study, the information we provide supports a holistic approach to addressing both illness perception and mental health; addressing one may lead to a favorable response in the other. Encouraging results from a previous randomized control trial of an illness perception intervention showed that better understanding of their condition, more favorable illness perception, and earlier return to work in the group that received the intervention [25].

Relationship between other variables and health perceptionOthers who may be at risk for worse health perception in our study include those of age < 75, some minority races/ethnicity groups, higher BMI, lower income, and those with an increasing number of comorbidities. Age over 75 was associated with higher odds of reporting PPHS. This differs from previous findings, where older age was associated with a decline in subjective health ratings [26, 27]. However, those studies found several moderators of these associations, including cognitive functioning, presence of physical illness, and religiosity [26, 28, 29].

Post-MI and post-stroke patients identifying as NH Black/AA or Hispanic had significantly lower odds of reporting PPHS than NH White patients (Tables 1 and 2). One cross-sectional study of US adults also found that NH Black/AA patients had a higher prevalence of poor/fair perceived health status compared to NH White patients [30]. Our findings may provide insight into health status perception as an additional potential mediator of racial/ethnic disparities in adverse cardiovascular events. One large observational cohort study found that Black patients had 72% higher CVD mortality hazard after adjusting for age and sex than White patients [33]. Further investigation should be conducted to better understand the perception of health status in Black, Hispanic, and other minority populations, and how to address health perception in addition to the social determinants of health to minimize the existing disparities in adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Finally, household income was found to be related to PPHS in both groups, while being overweight was associated with NPHS in post-MI patients (Tables 1 and 2). This supports previous research showing individuals with higher BMI are less likely to view themselves as healthy [31, 32]. One study found that self-perceived income had a greater impact on health perception than objective income level [34].

Our findings reinforce the need for mental health screening and treatment in patients who experience an adverse CVD event. Perception of health status can influence health behaviors, the processing of health information, and healthcare decision making [35]. This includes the adherence to cardiac rehabilitation and post-MI or post-stroke care, which are crucial to achieving positive cardiovascular outcomes for patients [13]. By addressing patients’ mental health and promoting more positive health status perception, providers can improve the cardiovascular and psychological outcomes of their patients after a CVD event. Thus, it is important that providers address health perception in addition to anxiety and depression in CVD event survivors.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the limitations of the NHIS 2019, as previously described [14, 15]. These include selection and non-response bias, as well as that data is self-reported. We applied sample weights provided by the NHIS to attenuate the risk of non-response bias. We use responses to the NHIS “rotating core” of questions not asked annually, therefore 2019 data was the most recently available data at the time this analysis was conducted. The relationships observed in this study may have been modified by the COVID-19 pandemic. We dichotomized variables to form the variables “anxious”, “depressed”, “PPHS”, and “NPHS”, to perform logistic regression analyses, thus we do not account for different levels of health perception. The cross-sectional nature of this analysis is an additional limitation, as we cannot assess temporality to understand if psychological distress led to illness perception or vice versa. Finally, we do not have longitudinal follow-up on subsequent health outcomes, so we cannot assess to what degree health perception mediates the known relationship between mood disorders and outcomes in patients who have had an MI or stroke.

Conclusions

Given the high prevalence of anxiety and depression among MI and stroke survivors, it is essential that providers consider the impact of mental health and illness perceptions on patient outcomes. Through a nationally representative dataset, we suggest that anxiety and depression are associated with worse illness perception in CVD event survivors, and that race, ethnicity, age, and other factors are also related to health status perception. Given the influence of illness perception on health behaviors and treatment plan adherence, it is crucial that providers address the mental health and health perception of their CVD patients.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NHIS repository, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/2019nhis.htm.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NHIS:

-

National Health Interview Survey

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- PHQ-8:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-8

- NPHS:

-

Negative perceived health status

- PPHS:

-

Positively perceived health status

- NH:

-

Non-Hispanic

- AA:

-

African American

- AIAN:

-

American Indian/Alaska Native

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lead Causes Death, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (2022).

Reitman E. Yale Study Examines Impact of Stress on Vascular Health, https://medicine.yale.edu/lab/vamos/news-article/yale-study-examines-impact-of-stress-on-vascular-health/ (2020).

Kuruppu S, Ghani M, Pritchard M, Harris M, Weerakkody R, Stewart R, Perera G. A prospective investigation of depression and adverse outcomes in patients undergoing vascular surgical interventions: a retrospective cohort study using a large mental health database in South London. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1).

Jackson CA, Sudlow CL, Mishra GD. Psychological distress and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in the 45 and up study: a prospective cohort study. Circulation: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(9):e004500.

Pimple P, Lima BB, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, Ramadan R, Levantsevych O, Sullivan S, Kim JH, Kaseer B, Shah AJ, Ward L. Psychological distress and subsequent cardiovascular events in individuals with coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Association. 2019;8(9):e011866.

Russ TC, Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Starr JM, Kivimäki M, Batty GD. Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;345.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–7.

Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat Reviews Cardiol. 2012;9(6):360–70.

Primessnig U, Pieske BM, Sherif M. Increased mortality and worse cardiac outcome of acute myocardial infarction during the early COVID-19 pandemic. ESC heart failure. 2021;8(1):333–43.

Cai C, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Gaffney A. Trends in anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1841–3.

Kennedy BM, Rehman M, Johnson WD, Magee MB, Leonard R, Katzmarzyk PT. Healthcare providers versus patients’ understanding of health beliefs and values. Patient experience journal. 2017;4(3):29.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. Contrib Med Psychol. 1980;2:7–30.

French DP, Cooper A, Weinman J. Illness perceptions predict attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(6):757–67.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey Methods, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/methods.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey 2019 Questionnaire Redesign, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/2019_quest_redesign.htm.

Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:24–31.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station. TX: StataCorp LLC; 2021.

Arnold SV, Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Li Y, Spertus JA. Perceived stress in myocardial infarction: long-term mortality and health status outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(18):1756–63.

Keller A, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Maddox T, Cheng ER, Creswell PD, Witt WP. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):677.

Medeiros GC, Roy D, Kontos N, Beach SR. Post-stroke depression: a 2020 updated review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:70–80.

Cai W, Mueller C, Li YJ, Shen WD, Stewart R. Post stroke depression and risk of stroke recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:102–9.

Northcott S, Moss B, Harrison K, Hilari K. A systematic review of the impact of stroke on social support and social networks: associated factors and patterns of change. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(8):811–31.

Rafsten L, Danielsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Anxiety after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(9):769–78.

Wearden AJ. Illness perception interventions for heart attack patients and their spouses: invited commentary. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(1):25–7.

Pinquart M. Correlates of subjective health in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2001;16(3):414.

Ribeiro EG, Matozinhos FP, Guimarães GD, Couto AM, Azevedo RS, Mendoza IY. Self-perceived health and clinical-functional vulnerability of the elderly in Belo Horizonte/Minas Gerais. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem. 2018;71:860–7.

Fernández-Jiménez C, Dumitrache CG, Rubio L, Ruiz-Montero PJ. Self-perceptions of ageing and perceived health status: the mediating role of cognitive functioning and physical activity. Ageing & Society 2022 Apr 27:1–20.

Sabha NU, Ghani M, Kausar S, Kausar F, Qamar M. Perceived health status of geriatric population living in old age homes and their access to health care facilities. Biomedica. 2022;38(1):33–8.

Mahajan S, Caraballo C, Lu Y, Valero-Elizondo J, Massey D, Annapureddy AR, Roy B, Riley C, Murugiah K, Onuma O, Nunez-Smith M. Trends in differences in health status and health care access and affordability by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1999–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(7):637–48.

Fonseca H, Gaspar de Matos M. Perception of overweight and obesity among portuguese adolescents: an overview of associated factors. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15(3):323–8.

Yancey AK, Wold CM, McCarthy WJ, Weber MD, Lee B, Simon PA, Fielding JE. Physical inactivity and overweight among Los Angeles County adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2):146–52.

Post WS, Watson KE, Hansen S, Folsom AR, Szklo M, Shea S, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: the mesa study. Circulation. 2022;146(3):229–39. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.122.059174.

Cialani C, Mortazavi R. The effect of objective income and perceived economic resources on self-rated health. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–2.

Klein WM, Stefanek ME. Cancer risk elicitation and communication: Lessons from the psychology of risk perception. Cancer J Clin; 57: 147–67.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the NHIS survey, conducted by the US CDC National Center for Health Statistics.

Funding

The authors did not receive financial support to conduct this research or prepare this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AN, KA, JL, and CTL contributed to study design. AN and KA conceptualized the research question and led the design of the study. JL led the analysis, AN led manuscript preparation, and KA led the literature review. All authors contributed to writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Narendrula, A., Ajani, K., Lang, J. et al. Psychological distress and health perception in patients with a previous myocardial infarction or stroke: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23, 430 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03422-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03422-5