Abstract

Background

Current guidelines indicate we can consider a bridging strategy that uses intravenous, reversible glycoprotein inhibitors for patients that required surgery following recent stent implantation. However, no strong clinical evidence exists that demonstrates the efficacy and safety of this treatment. Therefore, in this study, the efficacy and safety of a bridging strategy that uses intravenous platelet glycoprotein receptor inhibitors will be evaluated.

Methods

A meta-analysis was performed on preoperative bridging studies in patients undergoing coronary stent surgery. The primary outcome was the success rate of no major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The secondary outcomes were the success rate of no reoperations to stop bleeding.

Results

A total of 10 studies that included 382 patients were used in this meta-analysis. For the primary endpoint, the success rate was 97.7% (95% CI 94.4–98.0%) for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, 98.8% (95% CI 96.0–100%) for tirofiban (6 studies) and 95.8% (95% CI 90.4–99.4%) for eptifibatide (4 studies). For secondary endpoints, the success rate was 98.0% (95% CI 94.8–99.9%) for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, 99.7% (95% CI 97.1–100%) for tirofiban (5 studies), and 95.3% (95% CI 88.5–99.4%) for eptifibatide (4 studies).

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the use of intravenous platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors as a bridging strategy might be safe and effective for patients undergoing coronary stent implantation that require surgery soon after.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Current guidelines recommend that patients diagnosed with stable coronary artery disease with stent implants should receive dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) that uses a P2Y12 inhibitor and aspirin for 6 months and patients with acute coronary syndrome for 12 months unless they show contraindications such as bleeding [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, approximately 5% of patients undergo surgery in the first year following their percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [7,8,9]. Dual antiplatelet therapy increases the intra and perioperative bleeding risk, and surgery is associated with pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic effects; therefore, increasing the risk of coronary thrombosis at the level of the stented vascular segment and throughout the coronary vasculature [10].

Recent guidelines indicate that intravenous antiplatelet drugs may be considered for perioperative bridging treatment. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no strong clinical evidence that demonstrates the efficacy of bridging with either parenteral antiplatelet therapies [1, 3]. Therefore, in this meta-analysis, the efficacy and safety of a bridging strategy that uses intravenous platelet glycoprotein receptor inhibitors will be evaluated.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted to identify relevant studies within databases, such as PubMed (January 1, 1946, to November 15, 2020), EMBASE (January 1, 1974, to November 15, 2020), and the Cochrane Library (inception to November 15, 2020). As a result, the following keywords were used: antiplatelet therapy, aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, prasugrel, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab, tirofiban, eptifibatide, and surgery.

Any experimental and observational studies were included except for case reports without any limits and language restrictions. These studies described the use of an intravenous antiplatelet bridging treatment strategy for patients with coronary heart disease that had a stent implanted within 6 months of when surgery was planned.

Two reviewers independently extracted the data and contacted the relevant authors to obtain detailed data when the information was not comprehensive. Disagreement was resolved through negotiation. In addition, when there was no consensus, a recommendation from a third reviewer was involved.

Finally, 18 evaluation checklists were formed based on improvements to the Delphi technology. They were used to evaluate the quality of the case series study methodology. Each study counted the total number of positive items based on the consensus of the reviewers. This methodological quality assessment checklist did not recommend using scoring methods but gave corresponding options for each item. If the study met 14 (70%) or more checklist parameters, it was considered acceptable.

The primary outcome of this meta-analysis was the success rate of no major adverse cardiac events defined by each study, such as myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, cardiogenic shock, sudden cardiac death, and death. The secondary outcome was the success rate of no reoperation to stop bleeding as defined by each study.

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (Stata15, USA) software. To calculate the success rate of the bridging treatment, calculations were based on two aspects, avoiding major adverse cardiovascular events (primary endpoint) and avoiding reoperation due to bleeding (secondary endpoint). Cochrane Q statistic (p-values ≤ 0.1 were considered significant) and I2 statistic (25%, 50%, and 75% were associated with low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively) were used to evaluate the heterogeneity between various studies. Publication bias was assessed using Egger's test (p < 0.1). In addition, the sensitivity was evaluated to ensure the robustness of the results, and subgroup analysis was conducted after the bridge therapy drugs were separated (tirofiban and eptifibatide).

Results

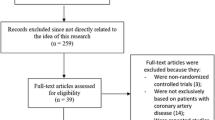

The initial search yielded 582 unique studies for review (Fig. 1). Following the screening, a full-text review was conducted on 50 special reports. Finally, 11 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis. Out of 11 studies, 10 provided sufficient details for meta-analysis. The key characteristics and findings of the included studies, which included two prospective and eight observational studies, are given in Table 1. Other important details of each article are shown in Table 2.

This study included ten studies [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] with 382 patients. Among them, 6 studies [11, 12, 14, 16,17,18] included 215 patients that used tirofiban for bridging therapy. Four studies [13, 15, 19, 20] had 167 patients that used eptifibatide for bridging therapy.

MACE was reported in all studies included, while reoperation due to bleeding was reported in seven studies. Walker 2017 mentioned that four bleeding events occurred in all patients, three minimal TIMI bleeding, one minor TIMI bleeding, and only one required blood transfusion and drug discontinuation. The results of Polito 2018 suggested three cases of uncomplicated anemia in bridging patients after surgery. So we believed that there were no cases of reoperation due to bleeding in these studies and included them in the calculation. Reoperation due to bleeding might be considered the most objective safety endpoint because it does not depend on the different criteria adopted for bleeding transfusion. All studies included were supposed to be of acceptable quality according to the modified Delphi technique (Table 3) [21].

Among the 382 patients, 367 did not show any major adverse cardiac events, and the success rate was 97.7% (95% CI 94.4–98.0%). According to the results of six studies, the success rate of tirofiban was 98.8% (95% CI 96.0–100%). In addition, the success rate of eptifibatide was 95.8% (95% CI 90.4–99.4%) based on the results of four studies (Fig. 2a). The risk of publication bias appeared to be low (p = 0.508, 95% CI − 0.391 to 0.727) (Fig. 3a). The findings were robust to sensitivity analyses performed for bias, study design, type of operation, and the variations in estimate modeling mentioned previously (Fig. 4a).

Because each study used a different definition of bleeding, and each patient underwent another kind of surgery, the risk of bleeding differed. Therefore, reoperation due to bleeding was considered the secondary endpoint of the study. Among the 382 patients, 369 did not record reoperation due to bleeding, and the success rate was 98.0% (95% CI 94.8–99.9%). According to the results from six studies, the success rate of tirofiban was 99.7% (95% CI 97.1–100%). The success rate of eptifibatide was 95.3% (95% CI 88.5–99.4%) based on the results of four studies (Fig. 2b). The risk of publication bias appeared to be low (p = 0.11, 95% CI − 0.227 to 1.145) (Fig. 3b), and sensitivity analysis was robust (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

This study showed that the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for bridging antiplatelet therapy might be safe and effective for patients undergoing coronary stent implantation that require surgery within 6 months and whose bleeding was classified as high risk. However, the intensive care unit must perform the bridging treatment with sufficient monitoring and testing conditions.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa are receptors on the surface of platelets that mediate the binding of fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and vitronectin to platelets, which cause platelets to cross-link and aggregate. Abciximab, tirofiban, and eptifibatide block this process in a targeted manner. Tirofiban and eptifibatide have a shorter action time, and their platelet inhibitory effect can last for 2–4 h following administration [22].

The previous studies [23] found that in patients with coronary heart disease that underwent non-cardiac surgery within 1 month of coronary stent implantation, the incidence of perioperative death, acute myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, and other cardiac adverse events was as high as 30%; in 2 out of 6 of cases, surgery was performed at the end of the month, and the incidence of the previously mentioned adverse events decreased to 10–15%; after 6 months, the incidence of surgery decreased to < 10%. Therefore, for patients with coronary stent implantation, if surgery with a high risk of bleeding is planned, it is necessary to carefully assess the advantages and disadvantages (e.g., the risk of cardiovascular complications that are caused by discontinuing antiplatelet drugs and the risk of bleeding caused by continuing drugs).

According to a multidisciplinary management opinion [24], in patients > 12 months after PCI, the risk of perioperative thromboembolism was low, and therefore, elective surgery could be performed. In patients < 12 months after PCI, the time for elective operation should be determined based on several factors. In summary, elective surgery should be performed ≥ 2 weeks after coronary artery balloon dilation, ≥ 1 month after implantation of a BMS, and ≥ 3 months after the implantation or elective surgery is performed again. For the new generation of DES, the time could be appropriately shortened based on the situation, and elective surgery should be performed ≥ 12 months after implantation of a bioabsorbable stent (BVS).

The risk of bleeding during the perioperative period is mainly affected by the type of surgery or the invasive nature of the procedure. In general, any long-duration (> 45 min) surgery and surgery on vital organs (e.g., central nervous system and heart), blood-rich organs (e.g., liver and spleen), large blood vessels, active fibrinolytic sites (i.e., the urinary system) and invasive procedures should be considered to have a high risk of bleeding [25, 26]. In patients treated with antiplatelet drugs before surgery, the PRECISE‑DAPT score could be used to evaluate the patient’s risk of bleeding [27].

This study has two main limitations. First, the included studies were observational and were not randomized controlled experiments. Second, the included studies used a different definition of bleeding; therefore, only the success rate of freedom from reoperation without bleeding was included.

Conclusions

In patients that require surgery after recent stent implantation, a bridging strategy that uses intravenous platelet glycoprotein receptor inhibitors might allow the temporary discontinuation of dual antiplatelet drugs without increasing the risk of bleeding. The decision to perform bridging treatment and careful risk stratification of ischemic events and bleeding requires strict cooperation between surgeons, cardiologists, and anesthesiologists. Large-scale randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm this result further.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- BMS:

-

Bare-metal stent

- DES:

-

Drug-eluting stent

- DAPT:

-

Dual antiplatelet therapy

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- BVS:

-

Bioabsorbable stent

References

Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–60.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1235–50.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2016;134:e123–55.

Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407–77.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–77.

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020;42(14):1289–367.

Rossini R, Capodanno D, Lettieri C, Musumeci G, Nijaradze T, Romano M, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and long-term prognosis of premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:186–94.

Gandhi NK, Abdel-Karim AR, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Frequency and risk of noncardiac surgery after drug-eluting stent implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:972–6.

Berger PB, Kleiman NS, Pencina MJ, Hsieh WH, Steinhubl SR, Jeremias A, et al. Frequency of major noncardiac surgery and subsequent adverse events in the year after drug-eluting stent placement results from the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:920–7.

Rajagopalan S, Ford I, Bachoo P, Hillis GS, Croal B, Greaves M, et al. Platelet activation, myocardial ischemic events and postoperative non-response to aspirin in patients undergoing major vascular surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2028–35.

Xia JG, Qu Y, Shen H, Liu XH. Short-term follow-up of tirofiban as alternative therapy for urgent surgery patients with an implanted coronary drug-eluting stent after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24:522–6.

Walker EA, Dager WE. Bridging with tirofiban during oral antiplatelet interruption: a single-center case series analysis including patients on hemodialysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:888–92.

Waldron NH, Dallas T, Erhunmwunsee L, Wang TY, Berry MF, Welsby IJ. Bleeding risk associated with eptifibatide (Integrilin) bridging in thoracic surgery patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;43:194–202.

Savonitto S, D’Urbano M, Caracciolo M, Barlocco F, Mariani G, Nichelatti M, et al. Urgent surgery in patients with a recently implanted coronary drug-eluting stent: a phase II study of “bridging” antiplatelet therapy with tirofiban during temporary withdrawal of clopidogrel. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104:285–91.

Rassi AN, Blackstone E, Militello MA, Theodos G, Cavender MA, Sun Z, et al. Safety of “bridging” with eptifibatide for patients with coronary stents before cardiac and non-cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:485–90.

Polito MV, Asparago S, Galasso G, Farina R, Panza A, Iesu S, et al. Early myocardial surgical revascularization after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in multivessel coronary disease: bridge therapy is the solution? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2018;19:120–5.

Marcos EG, Da Fonseca AC, Hofma SH. Bridging therapy for early surgery in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation. Neth Heart J. 2011;19:412–7.

De Servi S, Morici N, Boschetti E, Rossini R, Martina P, Musumeci G, et al. Bridge therapy or standard treatment for urgent surgery after coronary stent implantation: analysis of 314 patients. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016;80:85–90.

Ben Morrison T, Horst BM, Brown MJ, Bell MR, Daniels PR. Bridging with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors for periprocedural management of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug eluting stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79:575–82.

Barra ME, Fanikos J, Gerhard-Herman MD, Bhatt DL. Bridging experience with eptifibatide after stent implantation. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2016;15:82–8.

Moga C, Guo B, Schopflocher D. Development of a quality appraisal tool for case series studies using a modified delphi technique. Edmonton, AB: Institute of Health Economics; 2012.

Koenig-Oberhuber V, Filipovic M. New antiplatelet drugs and new oral anticoagulants. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(Suppl 2):ii74–84.

Savonitto S, Caracciolo M, Cattaneo M, De Servi S. Management of patients with recently implanted coronary stents on dual antiplatelet therapy who need to undergo major surgery. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2133–42.

Rossini R, Tarantini G, Musumeci G, Masiero G, Barbato E, Calabrò P, et al. A multidisciplinary approach on the perioperative antithrombotic management of patients with coronary stents undergoing surgery: surgery after stenting 2. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:417–34.

Hornor MA, Duane TM, Ehlers AP, Jensen EH, Brown PS Jr, Pohl D, et al. American college of surgeons’ guidelines for the perioperative management of antithrombotic medication. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227:521-36.e1.

Baron TH, Kamath PS, McBane RD. Management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing invasive procedures. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2113–24.

Costa F, van Klaveren D, James S, Heg D, Räber L, Feres F, et al. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual-patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet. 2017;389:1025–34.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (No. cstc2020jcyj-msxmX0853), the Joint Medical Research Project of Chongqing Municipal Science and Health Commission (No. 2020MSXM094), and the Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of Chongqing Municipal Health Commission (No. ZY201802121). The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FW: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing original draft. KM: Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing review & editing. RX: Project administration; Resources. BH: Software; Writing review & editing. JC: Supervision; Validation. ZZ: Supervision; Validation. YL: Software; Validation. MM: Funding acquisition; Methodology. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, F., Ma, K., Xiang, R. et al. Efficacy and safety of a bridging strategy that uses intravenous platelet glycoprotein receptor inhibitors for patients undergoing surgery after coronary stent implantation: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 22, 125 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02563-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-022-02563-3