Abstract

Background

Unruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm (SOVA) are typically asymptomatic, and hence can be easily ignored. Ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm (RSOVA) usually protrude into the right atrium or ventricular. However, in this case, the RSOVA protruded into the space between the right atrium and the visceral pericardium leading to compression of the right proximal coronary artery. Very few such cases have been reported till date.

Case presentation

We describe a case of ruptured right SOVA in a 61-year-old man with syncope and persistent hypotension. At the beginning, considered the markedly elevated troponin, acute myocardial infarction was considered. However, emergency coronary angiography unexpectedly revealed a large external mass compressed right coronary artery (RCA) resulting in severe proximal stenosis. Then, aorta computed tomography angiography (CTA) and urgent surgery confirmed that the ruptured right SOVA led to external compression of the right proximal coronary artery. Finally, ruptured right SOVA repair and RCA reconstruction were successfully performed, and the patient was discharged with no residual symptoms.

Conclusions

It is very important to be vigilant about the existence of SOVA. RSOVA should be suspected in a patient presenting with acute hemodynamic compromise, and echocardiography should be immediately performed. Moreover, it is very important to achieve dynamic monitoring by using cardiac color ultrasound. Definitive diagnosis often requires cardiac catheterization, and an aortogram should be performed unless endocarditis is suspected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Sinus of valsalva aneurysm (SOVA) is usually a congenital anomaly in which a dilatation of the aortic wall is located between the aortic valve and the sinotubular junction. It is rare, estimated at 0.09% of the population, and while they do not always rupture, which usually remains undetected until rupture [1]. SOVA is found most often in the right coronary sinus (RCS), less often in the noncoronary sinus (NCS), and least often in the left coronary sinus. Once ruptured, SOVA can protrude into any of the heart chambers, usually the right atrium or the right ventricle. Occasionally, it ruptures into the pulmonary artery or interventricular septum [2]. Ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm (RSOVA) is a rare but well-recognized clinical entity, with a higher incidence in oriental patients than in western populations [3]. Smaller ruptures tend to have a slower onset of symptoms and may be found incidentally, however, it can be catastrophic with significant hemodynamic effects and various symptoms [1].

In this case, we describe the RSOVA protruded into the space between the right atrium and the visceral pericardium, resulting to compression of the right proximal coronary artery. Then, acute myocardial infarction and shock were developed. Very few such cases have been reported till date. Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool for this lesion, however, the sensitivity and accuracy of echocardiography is limited, especially in an emergency. In this case, only a small amount of pericardial effusion was found in emergency transthoracic echocardiography. Emergency coronary angiography showed severe proximal right coronary artery (RCA) stenosis, which was related to the external compression of a large mass. Aorta computed tomography angiography (CTA) and urgent surgery confirmed that the ruptured right SVA led to external compression of the right proximal coronary artery. Finally, ruptured right SOVA repair and RCA reconstruction were successfully performed, and the patient was discharged with no residual symptoms.

Case description

A 61-year-old man was transferred to the emergency department because of fainting. He did not present with any prodromal symptoms before this catastrophic event. Approximately two hours before admission, the patient fainted and was found unresponsive in his bathroom. He regained consciousness after about 30 min. He was admitted to the hospital with persistent confusion, weakness, nausea, dry retching, and cold diaphoresis. His arms and legs were cold and clammy, with no edema. Distal pulse was weak. On arrival at the hospital, additional medical history was obtained from his wife. He had a previous smoking history of one pack/day, but no alcohol or illicit drug use history. His father had hypertension, while his mother had diabetes mellitus. There was no other significant medical, surgical, or family history of any cardiovascular disease. In the emergency department, the systolic blood pressure was 67–70 mm Hg, the heart rate was 106 beats/minute, the respiratory rate was 22 breaths/minute, and the oxygen saturation was 98%, while he was breathing 3 l of oxygen through a nasal cannula. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) performed within 10 min of arrival was normal. Bedside troponin I level was ≤ 0.05 ng/ml (normal range 0–0.4). Three hours later, the laboratory high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) T was elevated, at 104.500 pg/ml (normal range 0–14), and six hours later, it had increased to 841.100 pg/ml. The repeat ECG showed atypical non-ischemic changes. Other test results are shown in Table 1.

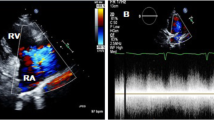

Emergency transthoracic echocardiography was performed to evaluate cardiac function, which revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60%, and a small volume of pericardial effusion with an 8 mm liquid dark area in the apex of the heart, 8 mm in left ventricular lateral wall, and 5 mm in right ventricular lateral wall. No major myocardial wall motion abnormalities were seen at the initial evaluation by the emergency physician. Bedside color Doppler ultrasound imaging of abdomen and urinary bladder was normal. After normal saline and norepinephrine were administered, the patient’ condition was relatively stable. Then he was transferred for percutaneous coronary intervention for suspected acute coronary syndrome. Emergency coronary angiography (Fig. 1) showed severe proximal RCA stenosis, which was related to the external compression due to a large mass (30 mm × 45 mm). It also showed severe cardiac hypokinesia, possibly caused by circumferential pericardial effusion. The patient was immediately transferred for complete aorta CTA to achieve an accurate and rapid diagnosis, and for guiding surgery. The aorta CTA revealed the presence of a giant outward aneurysm (40 mm × 34 mm; Fig. 2) of aortic root, which was compressing the ostium of the RCA, as well as moderate pericardial effusion. The patient was rushed to the cardiac surgery unit. The intra-operative findings included moderate hemorrhagic pericardial effusion (about 400 ml), massive blood clot on the right atrioventricular surface, ruptured right SVA, ruptured ostium of RCA, hematoma on the right atrial side and medial pulmonary artery (Fig. 3). Ruptured right SVA repair and RCA reconstruction were successfully performed. Finally, the patient was discharged with no residual symptoms. The ECG after surgery is shown in Fig. 4.

Coronary angiography. Coronary angiography was performed on the patient nine hours after arriving at the emergency department. Coronary angiography showed severe stenosis of the proximal RCA (Panel A, arrow). The right coronary artery was compressed by the external aortic right coronary sinus aneurysm (Panel B, arrow)

Intraoperative image. A giant hematoma was seen in the aortic root. Surgery confirmed that the hematoma was originating from the aortic right coronary sinus, thereby causing external compression of the right coronary artery. Ruptured SVA protruded into the space between the right atrium and the visceral pericardium

Electrocardiogram. Electrocardiograms obtained on the evening of surgery (A) and day 2 after surgery (B). 12-lead electrocardiography showed sinus rhythm. A: T-wave flat in I, aVL and V1 through V6 leads, q waves visible in II, III and aVF leads, ST-segment slight elevation in II, III and aVF leads. B: ST-segment horizontal elevation in II, III, aVF leads and V5 through V6 leads

Discussion and conclusion

In this case, the RSOVA protruded into the space between the right atrium and the visceral pericardium, which led to compression of the right proximal coronary artery. Very few such cases have been reported till date. RSOVA can present as formation of shunting, which may rapidly affect the hemodynamic status.

A prompt differential diagnosis between acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and acute aortic disease (AAS) is difficult. Both need rapid diagnosis and decision-making to reduce the extremely poor prognosis. AAS includes aortic dissection, pseudoaneurysm, aortic rupture, traumatic aortic injury [4]. In this case, fainting was the initial symptom, and upper abdominal pain developed after arriving at the emergency department. The most prominent feature of the patient’s presentation was cardiogenic shock. However, elevated troponin level was discordant with the extent of ventricular dysfunction based on the emergency coronary angiography, so the most likely diagnosis was AAS.

Transthoracic echocardiography is the first-line diagnostic tool for aneurysm, because it can clearly visualize the aneurysm walls and the disturbed blood flow at the site of perforation [5]. However, the sensitivity and accuracy of echocardiography is limited, especially in an emergency (6). CTA can provide additional 2-D or 3-D anatomical information due to its high resolution, which can play an important role in achieving an accurate and rapid diagnosis, and for guiding surgery. In this case, the primary impression was coronary artery disease. In addition, SOVA in the patient was not recognized by transthoracic echocardiography in the emergency department due to the absence of structural anomalies and shunt locations. We hypothesize that the laceration of the aortic sinus may be too small to be detected by emergency beside transthoracic echocardiography. As the disease progresses, emergency coronary angiography found severe stenosis of the proximal RCA resulting from a massive external compression. Next, aortic CTA confirmed the presence of a giant outward aneurysm of aortic root, which was compressing on the ostium of the RCA, and provided excellent anatomical guidance for the surgery. Finally, the patient underwent emergency excision of the right coronary sinus aneurysm, patch repair, and pericardial effusion drainage. The patient recovered uneventfully, and was discharged on postoperative day 20. At his follow-up visit one year later, he had been hemodynamically stable, without any discomfort.

This case highlights the importance of being vigilant about the existence of SOVA. RSOVA should be suspected in a patient presenting with acute hemodynamic compromise, and echocardiography should be immediately performed. Definitive diagnosis often requires cardiac catheterization, and an aortogram should be performed unless endocarditis is suspected.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SOVA:

-

Sinus of valsalva aneurysm

- RSOVA:

-

Ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- hs-cTn:

-

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- AAS:

-

Acute aortic disease

References

Feldman DN, Roman MJ. Aneurysms of the sinuses of valsalva. Cardiology. 2006;106(2):73–81.

Dev V, Goswami KC, Shrivastava S, et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis of aneurysm of the sinus of valsalva. Am Heart J. 1993;126(4):930–6.

Chu SH, Hung CR, How SS, et al. Ruptured aneurysms of the sinus of valsalva in oriental patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;99(2):288–98.

Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;41:1169–252.

Attias D, Messika-Zeitoun D, Cachier A, et al. A multi-perforated man: asymptomatic ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm associated with an atrial and ventricular septal defect. Eur Heart J - Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;9(2):301–2.

Fujimoto S, Kondo T, Kodama T, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography-based coronary risk stratification in subjects presenting with no or atypical symptoms. Jpn Circ J. 2012;76(10):2419.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to doctors Ming Gang Zhou (Cardiology), Yong Liang (Radiology) and Jing Ze Li (Cardiac surgery) for providing our photographs of coronary angiography, aortic CTA, and intraoperative.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GYZ was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. TX contributed to conception the manuscript. PYZ revised the manuscript. LL and QT collected all relevant pictures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. The copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhuo, G.Y., Zhang, P.Y., Luo, L. et al. Ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm presenting as syncope and hypotension: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21, 449 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02247-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02247-4