Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of regularity in treatment follow-up appointments on treatment outcomes among hypertensive patients attending different healthcare settings in Islamabad, Pakistan. Additionally, factors associated with regularity in treatment follow-up were also identified.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was undertaken in selected primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare settings between September, 2017 and December, 2018 in Islamabad, Pakistan. A structured data collection form was used to gather sociodemographic and clinical data of recruited patients. Binary logistic regression analyses were undertaken to determine association between regularity in treatment follow-up appointments and blood pressure control and to determine covariates significantly associated with regularity in treatment follow-up appointments.

Results

A total of 662 patients with hypertension participated in the study. More than half 346 (52%) of the patients were females. The mean age of participants was 54 ± 12 years. Only 274 (41%) patients regularly attended treatment follow-up appointments. Regression analysis found that regular treatment follow-up was an independent predictor of controlled blood pressure (OR 1.561 [95% CI 1.102–2.211; P = 0.024]). Gender (OR 1.720 [95% CI 1.259–2.350; P = 0.001]), age (OR 1.462 [CI 95%:1.059–2.020; P = 0.021]), higher education (OR 1.7 [95% CI 1.041–2.778; P = 0.034]), entitlement to free medical care (OR 3.166 [95% CI 2.284–4.388; P = 0.0001]), treatment duration (OR 1.788 [95% CI 1.288–2.483; P = 0.001]), number of medications (OR 1.585 [95% CI 1.259–1.996; P = 0.0001]), presence of co-morbidity (OR 3.214 [95% CI 2.248–4.593; P = 0.0001]) and medication adherence (OR 6.231 [95% CI 4.264–9.106; P = 0.0001]) were significantly associated with regularity in treatment follow-up appointments.

Conclusion

Attendance at follow-up visits was alarmingly low among patients with hypertension in Pakistan which may explain poor treatment outcomes in patients. Evidence-based targeted interventions should be developed and implemented, considering local needs, to improve attendance at treatment follow-up appointments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organisation report, hypertension is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the world and is responsible for nine million deaths every year [1]. Despite the availability of different treatment options, the rate of blood pressure control remains suboptimal [2, 3]. In the United States of America alone, the cost associated with uncontrolled hypertension accounts for $131 billion annually [4]. Patients with hypertension, including those with controlled blood pressure, are twice as likely to develop cardiovascular complications as compared to the patients without hypertension [5]. The risk of stroke and ischemic cardiac events can be reduced to one third if the systolic blood pressure is controlled below 140 mmHg [6]. Effective control of blood pressure can only be achieved through lifelong care and regular follow-up [7, 8]. Regular treatment follow-up is an important component of effective disease management especially for long term conditions [9, 10]. For patients with hypertension, treatment follow-up provides an opportunity for healthcare practitioners to adjust patient’s treatment regimen, assess patient’s adherence to the therapy, monitor any adverse effects and improve patient’s understanding of disease management [11,12,13]. The research has demonstrated that regular attendance at treatment follow-up appointments is associated with better treatment outcomes in patients with hypertension [8, 9, 14,15,16]. Several interventions have been tested to improve follow-up care among patients with chronic diseases. These interventions include increased awareness among patients regarding the benefits of follow-up care, providing free medications, free transport vouchers, telephone/sms reminders and appointment assistance. All these interventions have shown positive effect on regularity in follow-up care among patients [12, 17,18,19].

Although there is slight variation in recommendations for scheduling of treatment follow-up appointments among various hypertension treatment guidelines, all guidelines strongly recommend regular follow-up appointments to monitor treatment outcomes. The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidelines for management of arterial hypertension recommends frequent, at least once a month visit to a specialized healthcare facility until the optimal target blood pressure (BP) is achieved. Once the target BP is achieved a visit interval of few months is considered reasonable [20]. The American Heart Association (AHA) 2017 guidelines for prevention, detection, evaluation and management of high blood pressure in adults also recommend scheduling follow-up evaluation at monthly interval until target BP is achieved and should be reassessed every three to six months [21].

According to a recently published meta-analysis, the prevalence of hypertension in Pakistan was 26.4% [22]. The national health survey of Pakistan reported that only 50% of patients with hypertension in Pakistan were diagnosed and of those who were diagnosed, only 50% had ever received any treatment for hypertension [23]. Similarly the control rate of blood pressure was only 12.5% [23]. Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions are required for optimal management of hypertension [24]. Despite of its importance, no data is available on the regularity of follow-up appointments, predictors of regularity in follow-up appointments and association between regular follow-up visits and blood pressure control among patients with hypertension in Pakistan. The purpose of this study was to assess the regularity in hospital follow-up appointments, determining factors predicting regularity in hospital follow-up visits and to find out the impact of regular treatment follow-up visits on blood pressure control among hypertensive patients in Pakistan.. This paper is part of larger study evaluating the predictors of blood pressure control in Pakistan [3].

Material and methods

Ethics statement

The ethics approvals of the study were obtained from Bioethics committees/administrations of Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences Islamabad (tertiary care hospital), Government CDA Hospital, Sector G-6/2 Islamabad (secondary care hospital) and Government CDA Medical Centre, Sector I-10 Islamabad (primary healthcare setting) (Reference number. BFC-FBS-QAU-2018–108,Dated: 23/10/2018, F.1–1/2015/ERB/SZABMU Dated: 28/08/2017 and CDA/DHS-14(1) (63)/2018/1077 Dated: 09/10/2018). Informed written consent was obtained from each participant before enrolment in the study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the survey was guaranteed to each enrolled participant.

Study settings

The study was conducted in three different healthcare settings in Islamabad, the federal capital of Pakistan. These healthcare settings included one tertiary care hospital, one secondary care hospital and one primary healthcare clinic to allow better generalization of study findings.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using an online sample size calculator, Raosoft®. The overall minimum sample size was calculated to be 385 based on 95% confidence interval, 5% margin of error and 50% response distribution. We aimed to recruit at least 100 patients from each study center. The respondents were sampled consecutively from all study centers.

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional methodological approach was adopted. Three hundred and eight patients were recruited from tertiary care hospital, 203 patients from secondary care hospital and 151 patients from primary health care Centre (Fig.1). The participants were recruited from September, 2017 to December, 2018. All adult patients aged 18 and above, diagnosed with essential hypertension, using at least one antihypertensive medication and able to communicate in Urdu (Pakistan’s National Language) were invited to participate in the study. Patient’s hand-held record was used to ascertain their eligibility to participate in the study. Hypertensive patients with comorbidities were also included in the study. Pregnant women, patients with mental health illnesses affecting their cognitive abilities (e.g. dementia, Parkinson’s disease) and those who could not communicate in Urdu language were excluded from our study. Participation in the study was voluntary. Participants meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited using consecutive sampling strategy from each of the participating centres.

Data collection

A structured self-administered and self-reported questionnaire was used to assess the regularity in treatment follow-up appointments. However, for illiterate participants the questionnaires were administered by the interviewer. The data collection was divided into three steps. In the first step, a standard questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data of the patient. In the second step, patient’s medical record was reviewed and relevant clinical data were extracted including status of blood pressure control, number/nature of co-morbidities, medication history, risk factors and follow-up schedule advised to the patient. The follow-up schedule advised to the patient was used for the assessment of treatment follow-up regularity. In the third step, the participants were asked following questions relating to the regularity in treatment follow-up visits: When did you visit your doctor last time for treatment follow-up? Do you think that you visit your doctor regularly for treatment follow-up? After how many days/weeks/months do you visit your doctor for treatment follow-up? In last ten scheduled/advised visits, how many times have you missed your follow-up visit?. Eight items Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS-8) questionnaire was used to assess medication adherence [25,26,27,28]. The participants with MMAS-8 score ≤ 6 were considered as adherent to their prescribed antihypertensive therapy.

Outcome measures and covariates

The primary outcome measure was regularity in follow-up visits. A participant was considered as irregular in treatment follow-up visits if he/she had missed more than three out of 10 scheduled/advised follow-up visits [29,30,31]. The patients with hypertension were defined in accordance with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) treatment guidelines, 2011 for the management of hypertension. A blood pressure reading of 140/90 and 150/90 was considered controlled for patients aged less than 80 years and more than 80 years respectively. Similarly, for the patients with kidney failure, eye or cerebrovascular damage the blood pressure level under 130/80 mmHg was considered as controlled [32]. The covariates were age, marital status gender, education level, profession, entitlement status,smoking status, number of medications prescribed, duration of therapy, presence of comorbidities and medication adherence.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 was used to perform statistical analysis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The binary logistic regression analysis using Forward Likelihood Ratio method was used to identify predictors associated with regularity in treatment follow-up and blood pressure control. Correlation and Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test was performed to select best prediction model.

Results

A total of 662 patients with hypertension participated in the study. Of 662 patients, 315 (48%) were male and 346 (52%) were female. The mean (± S.D) age of participants was 54 (± 12) years. The mean (± S.D) duration of hypertension was 6 (± 6) years. The mean (± S.D) systolic blood pressure of participants was 148 mmHg (± 18) and mean (± S.D) diastolic blood pressure was 92 mmHg (± 11). The mean number of antihypertensive drugs used was 1.69 ± 0.7. Two hundred and sixty (39%) participants were obese. Two hundred and eighty-nine (44%) participants were using single antihypertensive agent and, 253 (38%) participants were entitled to free medical care. Two hundred and ninety (44%) participants had at least one co-morbidity. The prevalence of diabetes among participants was 15% 8% of participants had coronary artery disease [CAD], 1% patients had congestive heart failure [CHF] and 21% of participants had hyperlipidemia. The participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Less than half of the patients (41%) were regular in attending follow-up visits. Similarly, in terms of healthcare setting, the number of patients who were regular in attending their follow-up appointments in tertiary care, secondary care and primary care setting were 118 (38%), 123 (61%) and 33 (22%) respectively. (Table 2).

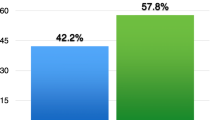

Out of 662 participants, 253 patients were entitled to free medical care. Of the patients who were entitled to free medical care, 150 (58%) participants regularly attended treatment follow-up appointments. Whereas the patients who were not entitled to free medical care, only 124 (31%) participants attended regular treatment follow-up appointments (P = 0.0001) (Table 2).

The results of binary regression analysis found that gender, age, higher education, entitlement status, treatment duration, number of medications, presence of co-morbidity, medication adherence and blood pressure control were significantly associated with regularity in treatment follow-up appointments. Similarly marital status, body mass index (BMI) and profession had no significant association with regularity in treatment follow-up visits. (Table 3).

For factors associated with treatment follow-up regularity, the results of binary regression analysis showed that males were 1.7 times more likely to regularly attend follow-up meetings compared to females (OR 1.720 [95% CI 1.259–2.3]). The participants aged ≥ 60 years of age were 1.5 times more likely to be regular in treatment follow-up visits than participants who were under 60 years of age (OR 1.462 [95% CI 1.059–2.020]). The participants who were entitled to free medical care were approximately three times more likely to attend follow-up appointments regularly compared with patients who were not entitled to free medical care (OR 3.166 [95% CI 2.284–4.388]). Patients with a co-morbidity were 3.2 times more likely to be regular in treatment follow-up visits than the patients without any co-morbidity (OR 3.214 [95% CI 2.248–4.593]). Patients with good medication adherence were approximately six times more likely to be regular in attending treatment follow-up appointments compared to patients with poor medication adherence (OR 6.231 [95% CI 4.264–9.106]) (Table 3).

Similarly, for blood pressure control the results of binary regression analysis showed that treatment follow-up regularity, age, number of anti-hypertensive medications and medication adherence had significant association with blood pressure control. On the other hand, gender, body mass index (BMI), level of education, employment status, marital status, entitlement status, treatment duration and presence of co-morbidity had no significant association with controlled blood pressure. The results of binary regression analysis further revealed that odds of controlled blood pressure in patients who were regular in their treatment follow-up visits were 1.5 times higher than the patients who were irregular in their treatment follow-up visits (OR 1.561 [95% CI 1.102–2.211]). Similarly, the odds of controlled blood pressure were 1.08 times higher in males as compared to females (OR 1.08 [95% CI 0.753–1.543]), being 60 years of age and above (OR 1.638 [95% CI 1.168–2.297]). being unmarried/divorced/widowed (OR 1.257 [95% CI 0.757–2.087]), being university graduate (OR 1.229 [95% CI 0.730–2.068]), being normal weight (OR 1.05 [95% CI 0.743–1.482), being an officer (OR 1.462 [95% CI 0.661–3.236]), being entitled to free medical care (OR 1.210[95% CI 0.858–1.707]), more than 05 years of treatment duration (OR 1.246[95% CI 0.875–1.776]), having co-morbidity (OR 1.072 [95% CI 0.733–1.568]), being adherent to prescribed pharmacotherapy (OR 2.720[95% CI 1.890–3.915]). On the contrary the odds of controlled blood pressure decrease with every unit increase in no. of prescribed anti-hypertensive medications (OR 0.689[95% CI 0.538–0.882]). (Table 4).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the regularity in attending treatment follow-up appointments, factors determining regularity in follow-up appointments and to evaluate the impact of regular treatment follow-up visits on treatment outcomes among patients with hypertension in Islamabad, Pakistan. Overall, attendance at treatment follow-up visits was poor. Furthermore, positive association between regular treatment follow-up and controlled blood pressure was observed among hypertension patients attending different healthcare settings. However, patients entitled to free medical care were more likely to attend treatment follow-up visits compared to the patients who had to pay from their own pocket.

Pakistan healthcare system consists of three tiers i.e. primary, secondary and tertiary healthcareand is run by both public and private sectors. Tertiary care hospitals are the teaching hospitals located in big cities of the country [23, 33]. Free healthcare coverage is available to only 27% of the population which mostly include government employees and members of the armed forces of Pakistan. They either receive free medicines and other healthcare services from the hospital or through reimbursement in case a medicine or a healthcare service is not available in the hospital. The remaining 73% population pay from their pockets for the healthcare services [34].

There is scarcity of research investigating the association between regularity in treatment follow-up appointments and blood pressure control not only in Pakistan but also in the South Asian region. In line with previous findings, we found a positive association between regular treatment follow-up and controlled blood pressure [8, 9, 15, 16, 35,36,37]. This positive association between regularity in treatment follow-up and controlled blood pressure could be due to the fact that the regular treatment follow-up visits provides an opportunity to healthcare providers to educate patients about their disease and drug therapy, optimize their therapy and to monitor treatment outcomes. There is a need to develop policies aiming at facilitating the patients in their treatment follow-up appointments to ensure better treatment outcomes.

Our results also suggest that entitlement to free medical care was significantly associated with regularity in treatment follow-up appointments. This finding is also consistent with previously reported studies [29, 38]. Unaffordability of healthcare services is the main issue in many lower-middle and low-income countries including Pakistan [39,40,41].. Health authorities should ensure that access to basic and specialised healthcare services is affordable for all the citizens.

A number of factors associated with regularity of treatment follow-up were identified in this study. It was observed that male patients were more regular in attending treatment follow-up appointments compared to the female patients. Gender differences in attending follow-up appointments have been reported for other disease conditions as well [42, 43]. However, studies conducted in the United Kingdom and Canada have reported that female patients were more likely to attend treatment follow-up visits compared to their male counterparts [14, 44]. The differences in the findings can be explained by the differences in cultural and social values. In Pakistan, females often need a male guardian to accompany them to the hospital and their attendance at. follow-up appointments depend on the availability of an accompanying person and this may lead to the less regularity in treatment follow-up among females. Female only clinics can potentially help overcome this barrier.

Age was found to be significantly associated with regularity in treatment follow-up visits. Previously, mixed results have been reported in literature for the association between age and regular attendance at follow-up appointments [14, 42,43,44,45]. Increased disease severity or the presence of other co-morbidities among old age patients may encourage elderly patients to regularly attend treatment follow-up appointments. However, some studies found negative correlation between age and regularity in treatment follow-up [46]. This negative correlation may be due to memory loss, non-availability of any caregiver or deteriorated health condition of the patient.

Our study found that patients with university level qualification were more likely to attend treatment follow-up visits. The results of our study are in line with previously conducted studies which also found a significant correlation between level of education and regularity in treatment follow-up visits [29, 47, 48]. Better disease knowledge and awareness about potential complications among university graduates may explain higher likelihood to attend treatment follow-up visits.

In line with the findings of a pervious study [46], we found significant positive correlation between the number of medications used and the regularity in treatment follow-up visits. A higher number of medications often means greater disease severity which could motivate patients to regularly attend their follow-up appointments. Similarly, in line with previous studies [14, 42], we found significant correlation between the presence of co-morbidity and regularity in treatment follow-up visits. Hypertension is often an asymptomatic disease so the patients do not feel need for regular treatment follow-up visits but the patients with any co-morbidity may perceive themselves sicker and seek medical help more frequently. Our study reported a very strong association between the medication adherence and regularity in treatment follow-up visits. This result is in line with previously conducted studies [49,50,51]. Similarly the result of our study suggests the significant correlation between the controlled blood pressure and regularity in treatment follow-up visits. Regularity in treatment follow-up visits increases the likelihood of controlled blood pressure in patients with hypertension. In every subgroup the patients who were regular in treatment follow-up visits had better rate of blood pressure control as compared to the patients who were regular in their treatment follow-up visits. These results are in line with the findings of previously conducted studies [8, 9, 14, 52]. This increased blood pressure control could be possibly because the regular follow-up visits provide healthcare practitioners an opportunity to adjust the treatment regimen, educate the patient and assess the patient’s adherence to prescribed pharmacotherapy, resulting in better treatment outcomes. Lastly high medication adherence was significantly associated with high rate of blood pressure control. The results of our study are self-explanatory and in line with a number of previous research studies than showed better treatment outcomes in patients with high medication adherence [3, 35, 53, 54].

Implications for clinical practice

The findings of our study have quite significant practice and policy implications. There is a need to design and implement interventions to improve attendance at treatment follow-up appointments. In this study, we have identified several factors associated with regularity in treatment follow-up visits like gender, age, level of education, entitlement status, treatment duration, number of medications, presence of co-morbidity, medication adherence and controlled blood pressure. Hence any intervention targeting at any of these factors could be helpful in improving attendance during treatment follow-up appointments. These interventions need to be patient specific and patient related factors such as age, gender, health beliefs, culture, traditions and disease knowledge should be kept in mind when designing any intervention to improve attendance at treatment follow-up visits. The intervention to increase regularity in treatment follow-up visits may include, providing entitlement to free medical care, educational interventions for educating the patients regarding the benefits of regular treatment follow-up, motivational interviewing, family support, providing better services at healthcare settings, providing incentives to the patients on every visit for follow-up, sending reminders to the patients through phone calls, sms, and emails etc. [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. There is a need to educate the patients who are at early stage of their disease to carefully follow the instructions provided by the healthcare professionals to halt further progression of their disease and its complications. Given that attendance at follow-up visits is associated with good BP control, healthcare professionals should emphasise the importance and purpose of attending follow-up visits during initial consultations. This will allow them to undertake required monitoring and optimise medicines to ensure best possible treatment outcomes for patients. In future studies, the distribution and causes of missed follow-up visits should also be explored in more detail.

Study limitations and future perspective

There are few limitations to our study findings. This study was conducted only in one city of Pakistan, hence generalisation of findings to small towns and villages should be made with caution. We used self-reported questionnaires to access the regularity in treatment follow-up visits. Self-reported questionnaire has its own inherent disadvantages/limitation like patients ability to understand the questions in questionnaire and participant’s willingness to disclose his/her information. This may result in over or underestimation of the results. In addition, completing questionnaires involves recall of previous events which may lead to recall bias in old age patients or those who had been on treatment for many years.

Conclusion

Regularity in treatment follow-up appointments was poor in patients with hypertension attending different healthcare settings in Islamabad, Pakistan. There is an association between blood pressure control and regularity in attending treatment follow-up appointments. On the basis of determining factors identified in our study, targeted interventions should be designed and implemented for better therapeutic outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The data can be obtained from the corresponding author under reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- mmHg:

-

Millimetre of mercury

- MMAS-8:

-

8-Items morisky medication adherence scale

- ESH:

-

European society of hypertension

- AHA:

-

American heart association

- NICE:

-

National institute for health and care excellence

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- SMS:

-

Short message service

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

References

W.H.0. A Global Brief on Hypertension A global brief on hypertension, silent killer, public health crisis. World Health Day, 2013 2013 [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/79059/WHO_DCO_WHD_2013.2_eng.pdf;jsessionid=F638668E0D914847E4B72CCAFB90BC63?sequence=1.

Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Gupta R, Avezum A, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310(9):959–68.

Mahmood S, Jalal Z, Hadi MA, Orooj H, Shah KU. Non-Adherence to prescribed antihypertensives in primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare settings in islamabad, pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Patient Preference Adherence. 2020;14:73.

Kirkland EB, Heincelman M, Bishu KG, Schumann SO, Schreiner A, Axon RN, et al. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: national estimates, 2003–2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(11):e008731.

Kelly TN, Gu D, Chen J, Huang J-F, Chen J-C, Duan X, et al. Hypertension subtype and risk of cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults. Circulation. 2008;118(15):1558.

He F, MacGregor G. Cost of poor blood pressure control in the UK: 62 000 unnecessary deaths per year. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17(7):455.

Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(3).

Fici F, Seravalle G, Koylan N, Nalbantgil I, Cagla N, Korkut Y, et al. Follow-up of antihypertensive therapy improves blood pressure control: results of HYT (HYperTension survey) follow-up. High Blood Pressure Cardiovas Prevent. 2017;24(3):289–96.

Zuo H-J, Ma J-X, Wang J-W, Chen X-R, Hou L. The impact of routine follow-up with health care teams on blood pressure control among patients with hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2019:1.

Xu W, Goldberg SI, Shubina M, Turchin A. Optimal systolic blood pressure target, time to intensification, and time to follow-up in treatment of hypertension: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h158.

Akinniyi AA, Olamide OO. Missed medical appointment among hypertensive and diabetic outpatients in a tertiary healthcare facility in Ibadan Nigeria. Trop J Pharmaceut Res. 2017;16(6):1417–24.

Macharia WM, Leon G, Rowe BH, Stephenson BJ, Haynes RB. An overview of interventions to improve compliance with appointment keeping for medical services. JAMA. 1992;267(13):1813–7.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–71.

Clement FM, Chen G, Khan N, Tu K, Campbell NR, Smith M, et al. Primary care physician visits by patients with incident hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(6):653–60.

Fontil V, Bibbins-Domingo K, Kazi DS, Sidney S, Coxson PG, Khanna R, et al. Simulating strategies for improving control of hypertension among patients with usual source of care in the United States: the blood pressure control model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1147–55.

Turchin A, Goldberg SI, Shubina M, Einbinder JS, Conlin PR. Encounter frequency and blood pressure in hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2010;56(1):68–74.

Kawasaki L, Muntner P, Hyre AD, Hampton K, DeSalvo KB. Willingness to attend group visits for hypertension treatment. Am J Managed Care. 2007;13(5):257–63.

Gates SJ, Colborn DK. Lowering appointment failures in a neighborhood health center. Med Care. 1976;14(3):263–7.

Baren JM, Boudreaux ED, Brenner BE, Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Clark S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of emergency department interventions to improve primary care follow-up for patients with acute asthma. Chest. 2006;129(2):257–65.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–104.

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252–89.

Shah N, Shah Q, Shah AJ. The burden and high prevalence of hypertension in Pakistani adolescents: a meta-analysis of the published studies. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):20.

Saleem F, Hassali AA, Shafie AA. Hypertension in Pakistan: time to take some serious action. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(575):449–50.

Mahmood S, Shah KU, Khan TM, Nawaz S, Rashid H, Baqar SWA, et al. Non-pharmacological management of hypertension: in the light of current research. Irish J Med Sci. 2019;188(2):437–52.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertension. 2008;10(5):348–54.

Al-Qazaz HK. Translation and validation study of Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS): the Urdu version for facilitating person-centered healthcare in Pakistan. Int J Person Centered Med. 2012;2(3):384–90.

Berlowitz DR, Foy CG, Kazis LE, Bolin LP, Conroy MB, Fitzpatrick P, et al. Effect of intensive blood-pressure treatment on patient-reported outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):733–44.

Bress AP, Bellows BK, King JB, Hess R, Beddhu S, Zhang Z, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(8):745–55.

Nwabuo CC, Dy SM, Weeks K, Young JH. Factors associated with appointment non-adherence among African-Americans with severe, poorly controlled hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103090.

Karter AJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, Ahmed AT, Ferrara A, Liu JY, et al. Missed appointments and poor glycemic control: an opportunity to identify high-risk diabetic patients. Med Care. 2004:110–5.

Ogedegbe G, Schoenthaler A, Fernandez S. Appointment-keeping behavior is not related to medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1176–9.

NICE. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [Internet]. Manchester, UK: Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management NICE guidelines 2011 [Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127.

Aslam L, Abdullah A, Ayub R. Analysis of Pakistan and Iran health care delivery system. Int J Innov Res Dev. 2014;3(7):308–12.

Punjani NS, Shams S, Bhanji SM. Analysis of health care delivery systems: pakistan versus united states. Int J Endorsing Health Sci Res. 2014;2(1):38–41.

Khayyat SM, Khayyat SMS, Alhazmi RSH, Mohamed MM, Hadi MA. Predictors of medication adherence and blood pressure control among Saudi hypertensive patients attending primary care clinics: a cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2017;12(1).

Jaam M, Ibrahim MIM, Kheir N, Hadi MA, Diab MI, Awaisu A. Assessing prevalence of and barriers to medication adherence in patients with uncontrolled diabetes attending primary healthcare clinics in Qatar. Primary Care Diabetes. 2018;12(2):116–25.

Guthmann R, Davis N, Brown M, Elizondo J. Visit frequency and hypertension. J Clin Hypertension. 2005;7(6):327–32.

Moy E, Bartman BA, Weir MR. Access to hypertensive care: effects of income, insurance, and source of care. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(14):1497–502.

Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, Walker DG, Brieger WR, Hafizur RM. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136(1):161–71.

Panezai S, Ahmad MM, Saqib SE. Factors affecting access to primary health care services in Pakistan: a gender-based analysis. Dev Pract. 2017;27(6):813–27.

O’Donnell O. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cadernos de saude publica. 2007;23:2820–34.

Saka B, Landoh DE, Patassi A, d’Almeida S, Singo A, Gessner BD, et al. Loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programs in Togo: risk factors and the fate of these patients. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15(1).

Santos E, Felgueiras Ó, Oliveira O, Duarte R. Factors associated with loss to follow-up in Tuberculosis treatment in the Huambo Province, Angola. Pulmonology. 2019;25(3):190.

Neal RD, Hussain-Gambles M, Allgar VL, Lawlor DA, Dempsey O. Reasons for and consequences of missed appointments in general practice in the UK: questionnaire survey and prospective review of medical records. BMC Family Practice. 2005;6(1):47.

Lalloo R, McDonald JM. Appointment attendance at a remote rural dental training facility in Australia. BMC oral health. 2013;13(1):36.

Kalyango JN, Hall M, Karamagi C. Appointment keeping for medical review among patients with selected chronic diseases in an urban area of Uganda. The Pan African medical journal. 2014;19.

Lee BW, Sathyan P, John RK, Singh K, Robin AL. Predictors of and barriers associated with poor follow-up in patients with glaucoma in South India. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(10):1448–54.

Alhamad Z. Reasons for missing appointments in general clinics of primary health care center in Riyadh Military Hospital, Saudi Arabia. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2(2):258–67.

Kunutsor S, Walley J, Katabira E, Muchuro S, Balidawa H, Namagala E, et al. Clinic attendance for medication refills and medication adherence amongst an antiretroviral treatment cohort in Uganda: a prospective study. AIDS research and treatment. 2010;2010.

Al-daken LI, Eshah NF. Self-reported adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients with hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2017;39(3):264–70.

Hsu Y-H, Mao C-L, Wey M. Antihypertensive medication adherence among elderly Chinese Americans. J Transcult Nurs. 2010;21(4):297–305.

Peppa M, Vlahakos D. Are we satisfied with the follow-up of hypertensive and chronic kidney disease patients in outpatient clinics? Hippokratia. 2011;15(Suppl 1):44.

Matsumura K, Arima H, Tominaga M, Ohtsubo T, Sasaguri T, Fujii K, et al. Impact of antihypertensive medication adherence on blood pressure control in hypertension: the COMFORT study. QJM. 2013;106(10):909–14.

Iloh GU, Ofoedu JN, Njoku PU, Amadi AN, Godswill-Uko EU. Medication adherence and blood pressure control amongst adults with primary hypertension attending a tertiary hospital primary care clinic in Eastern Nigeria. Afr J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2013;5(1).

Atherton H, Sawmynaden P, Sheikh A, Majeed A, Car J. Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(11).

Perry JG. A preliminary investigation into the effect of the use of the Short Message Service (SMS) on patient attendance at an NHS Dental Access Centre in Scotland. Primary Dental Care. 2011;18(4):145–9.

Lin H, Wu X. Intervention strategies for improving patient adherence to follow-up in the era of mobile information technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e104266.

Prasad S, Anand R. Use of mobile telephone short message service as a reminder: the effect on patient attendance. Int Dent J. 2012;62(1):21–6.

Lu Z, Cao S, Chai Y, Liang Y, Bachmann M, Suhrcke M, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for hypertension care in the community–a meta-analysis of controlled studies in China. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):216.

Levin RP. How to manage the behavior of patients who disregard scheduled appointment times. J Am Dental Assoc. 2012;143(2):172–3.

Jalal Z, Antoniou S, Taylor D, Paudyal V, Finlay K, Smith F. South Asians living in the UK and adherence to coronary heart disease medication: a mixed-method study. Int J Clin Pharmacy. 2019;41(1):122–30.

Jaam M, Hadi MA, Kheir N, Ibrahim MIM, Diab MI, Al-Abdulla SA, et al. A qualitative exploration of barriers to medication adherence among patients with uncontrolled diabetes in Qatar: integrating perspectives of patients and health care providers. Patient Preference Adherence. 2018;12:2205.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Donald E. Morisky, Department of Community Health Sciences, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, United States, for granting us permission to use the copyrighted MMAS-8. Use of the ©MMAS is protected by US copyright and registered trademark laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from: Donald E. Morisky, 294 Lindura Court, Las Vegas, NV 89138-4632; dmorisky@gmail.com

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M, K.U.S conceived the idea and designed the study; S.M., data collection; S.M., Z.J., M.A.H., data analysis; S.M., wrote initial draft; Z.J., M.A.H., reviewed and finalized the draft for submission, K.U.S., Z.J., research supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics approvals of the study were obtained from Bioethics committees/administrations of Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan, Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences Islamabad (tertiary care hospital), Government CDA Hospital, Sector G-6/2 Islamabad (secondary care hospital) and Government CDA Medical Centre, Sector I-10 Islamabad (primary healthcare setting) (Reference number. BFC-FBS-QAU-2018–108,Dated: 23/10/2018, F.1–1/2015/ERB/SZABMU Dated: 28/08/2017 and CDA/DHS-14(1) (63)/2018/1077 Dated: 09/10/2018). Informed written consent was obtained from each participant before enrolment in the study. The anonymity and confidentiality of the survey was guaranteed to each enrolled participant.

Consent to publish

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmood, S., Jalal, Z., Hadi, M.A. et al. Association between attendance at outpatient follow-up appointments and blood pressure control among patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 458 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01741-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01741-5