Abstract

Background

Cardiac rehabilitation is effective after coronary heart disease (CHD). However, risk factors remain, and patients report fear for recurrence during recovery. Problem-based learning is a pedagogical method, where patients work self-directed in small groups with problem solving of real-life situations to manage CHD risk factors and self-care. We aimed to demonstrate the better effectiveness of problem-based learning over home-sent patient information for evaluating long-term effects of patient empowerment and self-care in patients with CHD. Hypothesis tested: One year of problem-based learning improves patients’ empowerment- and self-efficacy, to change self-care compared to 1 year of standardised home-sent patient information after CHD.

Methods

Patients (N = 157) from rural and urban areas in Sweden between 2011 and 2015 (78% male; age.

68 ± 8.5 years) with CHD verified by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (70.1%) or coronary artery by-pass surgery (CABG) and CABG+PCI or myocardial infarction (29.9%) were randomly assigned to problem-based learning (experimental group; n = 79) or home-sent patient information (controls; n = 78). The problem-based learning intervention consisted of patient education in primary care by nurses tutoring groups of 6–9 patients on 13 occasions over 1 year. Controls received home-sent patient information on 11 occasions during the study year.

Results

At one-year follow-up, the primary outcome, patient empowerment, did not significantly differ between the experimental group and controls. We found no significant differences between the groups regarding the secondary outcomes e.g. self-efficacy, although we found significant differences for body mass index (BMI) [− 0.17 (SD 1.5) vs. 0.50 (SD 1.6), P = 0.033], body weight [− 0.83 (SD) 4.45 vs. 1.14 kg (SD 4.85), P = 0.026] and HDL cholesterol [0.1 (SD 0.7) vs. 0.0 mmol/L (SD 0.3), P = 0.038] favouring the experimental group compared to controls.

Conclusions

The problem-based learning- and the home-sent patient information interventions had similar results regarding patient empowerment, self-efficacy, and well-being. However, problem-based learning exhibited significant effects on weight loss, BMI, and HDL cholesterol levels, indicating that this intervention positively affected risk factors compared to the home-sent patient information.

Trial registration

NCT01462799 (February 2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronary heart disease (CHD), a life-long insidiously developing disorder, [1] is the leading cause of death globally [2]. Although treatments and secondary prevention have more than halved the CHD rates in high-income regions in Europe compared to the early 1980s, guidelines need to be optimised to decrease the future risk of mortality and myocardial infarction [3]. According to EUROASPIRE IV, most European patients with CHD do not enter cardiac rehabilitation programmes. Risk factors remain 1.35 years in median after secondary prevention; almost 50% of the smokers continued to smoke and persistent smokers were highest in patients < 50 years, around 40% had hypertension and were obese, 80% had hypercholesterolemia, and around 66% were physically inactive. Only 40% accomplished a physical activity level of vigorous intensity for 20 min one or more times a week, which is notable as the majority of the patients reported increasing physical activity levels after hospitalization [4].

Risk factor interventions after CHD are complex and challenging for patients [3, 5, 6]. In Sweden, patients continued to be at high risk and around 20% suffered another cardiovascular event during the first year after MI [7]. However, the future risk of mortality and myocardial infarction could decrease if new approaches to cardiac rehabilitation programmes were nurse coordinated [8] based on European guidelines involving multidisciplinary teams of health care professionals [4] with an effective and sustained contact with cardiologists and general practitioners [7]. Obviously, there is a need to strengthen cardiac rehabilitation interventions aiming to bridge the gap for patients between hospital- and primary care.

Multifaceted cardiac rehabilitation programmes that include patient education have decreased the risk for fatal and/or non-fatal cardiovascular events and increased health-related quality of life [9]. Knowledge about medication, cardiac symptoms, as well as behavioural changes such as increased physical activity, healthier diet, and smoking cessation were significantly related to patient education [10].

The World Health Organization emphasises the need for patients to be empowered as co-producers of their own health [11]. Patient empowerment was according to a concept analysis defined as a process facilitating patients to practice more influence over their health and thereby increase more control over questions, they themselves described as important [12]. An overview of systematic reviews concluded that patient empowerment interventions targeting a variety of patients with chronic diseases were promising avenues for promoting health [13]. In Sweden, patients are offered a brief cardiac rehabilitation programme in hospital care after a CHD event; when stable, they are referred to primary care without a structured follow-up of self-care.

However, our earlier research shows that patients’ beliefs about CHD, its medication and lifestyle habits vary qualitatively during recovery and may not lead to healthy choices. For example, patients sometimes consider CHD as impossible to affect [14]. Smoking have been described as harmless, and the use of medication have involved a cost-benefit analysis in which patients viewed the body as self-healing and able to control processes without influence of medication [15]. Such beliefs may lead to low medication adherence [16]. Moreover, most patient education in cardiac rehabilitation have not included patients’ beliefs, nor have adult learning principles [17] involving patients’ need to know what, how and why they learn been used. According to adult learning theory, for example problem-based learning, patients need to identify earlier knowledge and feel motivated to learn. Problem-based learning is a method characterised by a problem or a question portrayed in a scenario [18]. A small group of patients use the scenario as a starting point to trigger a problem solving process facilitated by a tutor, in this case a nurse [19]. The nurse does not act like a traditional teacher and do not provide facts and information to solve the problem. Instead, the nurse enact problem-based and self-directed learning to monitor and guide the patients’ learning process [20]. In problem-based learning patients have an investigative approach and are responsible and reflective on their own learning [21, 22], which may motivate patients to learn about self-care after an event of CHD. Thus, cardiac patients’ empowerment and beliefs about self-care might be improved by patient education that uses problem-based learning [23]. The need to compare adult learning theory, in this case problem-based learning and home-sent patient information [24], which we consider equally with traditionally learning theory, constitute the rational for the CORONARY heart disease in PRIMARY care (COR-PRIM) study [19].

Aim

The aim of the COR-PRIM study was to demonstrate the better effectiveness of patient problem-based learning over home-sent patient information for evaluating long-term effects of patient empowerment and self-care in patients with CHD.

Methods

Trial design

The COR-PRIM study was a prospective, randomised, parallel, and single centre study (NCT01462799) involving 157 patients with CHD in a primary care setting in south-eastern Sweden. The COR-PRIM study tested the hypothesis that 1 year of problem-based patient education improves a patients’ empowerment and self-efficacy, to change self-care significantly compared to 1 year of standardised home-sent patient information. Recruitment began in November 2011 and tests were performed at baseline [25] and one, three, and 5 years, which will be finalised in 2020, after completion of a one-year problem-based learning programme for patients with CHD. Here, we report only data from baseline and one-year follow-up, which was finally collected in 2015.

Patients

According to the COR-PRIM study, [19] the following inclusion criteria were used: (i) CHD verified by myocardial infarction and/or Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) and/or coronary artery by-pass surgery (CABG) within 12 months before planned start of the intervention irrespective of age; (ii) stable cardiac condition; (iii) optimised cardiac medication not substantially changed the previous month; and (iv) completed hospital heart school at one of the identified six primary health care centres. The following exclusion criteria were used: (i) planned CABG or other conditions demanding continuing cardiologic care such as on-going contact with heart failure clinic; (ii) life-expectancy ≤1 year; (iii) documented psychiatric disease impeding cooperation with other people; (iv) obvious abuse of alcohol or narcotics; and (v) inability to read or communicate in Swedish.

Randomisation and procedures

During a follow-up at hospital, nurses informed patients about the study and those patients who agreed to receive further information were contacted by the principal researcher by letter and telephone. Some patients voluntarily stated their reasons for not participating in the study – e.g., difficulties leaving work/home; long distance to the primary health care centres; and disapproval of group activity. The patients who agreed to participate, returned informed consent document and who had completed the baseline questionnaires were randomised (1:1 ratio) to either the experimental group (received problem-based learning) or the control group (received patient information leaflets delivered to the home address) before any intervention. The randomisation was carried out with sealed unmarked opaque envelopes and were assigned by an administrator in a room separated from the research and intervention area. We used a block of 18 study numbers that were blindly allocated to either problem-based learning or home-sent patient information [26]. The envelopes contained a unique number starting from number 1 that were hand-picked by an administrator who was blinded during this procedure.

Conventional care and interventions

All patients were offered a brief conventional cardiac rehabilitation programme at an outpatient clinic in hospital care that included counselling visits with a nurse and a cardiologist about 1 month and 6–12 months after discharge respectively; physical exercise 1–2 times per week, for 3–4 months and diet counselling. Additionally, patients were offered a day long heart school primarily focussing on CHD, medication, physical exercise, and diet. If the patient’s condition was stable, he or she was referred to a general practitioner in primary care. The conventional care provided and the design of the interventions are described below and in a previous paper [19]. Here, we provide a short description of the interventions.

Home-sent patient information group

The patients in the home-sent patient information group served as controls. After receiving conventional care, 6–9 patients per group met directly after randomisation in the primary health care centres to discuss self-care goals and follow-ups during the study year. Predetermined written patient information was provided [24] at this meeting to support self-care as suggested in brochures produced, for example, by The Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation. Next, the patient information was mailed to the patient’s home address at the same times as the problem-based meetings (explained below) during the study year. Finally, after 1 year of intervention the patients were invited to a focus-group interview to share their beliefs about their performance of self-care; experiences of the study materials and participating in the study.

Problem-based learning intervention group

The patients in the experimental group (6–9 patients/group) started the one-year problem-based learning intervention at a primary health care centre. There were 13 scheduled meetings, one in each of the following weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, 26, 39 and 52. Each meeting was for 2 h. The problem-based intervention was completed 1 year after start. The goal was to improve self-care by strengthening patient empowerment with a focus on understanding cardiac symptoms e.g. angina pectoris, swelling legs and dyspnoea, medications, and the health benefits associated with lifestyle changes regarding diet, physical activity, and mental health including depression, anxiety and fear. Nurses who were trained to tutor the patients in the problem-based learning process [27] were fundamental to this study. The nurses took part in a training session for 2 days given by the project team and later the nurses were tutored monthly by the authors, AKK and PT to discuss and develop their work. The training session included learning about tutoring, in problem-based learning regarding self-directed learning and problem-solving, to help patients to formulate issues and self-care goals. The patients used scenarios as triggers e.g. pictures, texts and concreate materials as a starting point for learning during the meetings. Moreover, the nurses supported the patients to choose learning materials and challenged patients to choose evidence-based literature. Resource professionals (e.g., physician and dietician) were invited to discuss questions not solved by the patients. Patients’ relatives were also invited to the meetings. During the final meeting, follow-up focus-group interviews were performed to collect data about patients’ beliefs about their performance of self-care and about their experiences of participating in the study. For further descriptions, see Kärner et al. [19].

Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient empowerment to reach self-care goals 1 year after randomisation. The questionnaires used to assess the primary and secondary outcomes are briefly presented here and more thoroughly elsewhere [25]. Patient empowerment was assessed using the Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale 10 which was developed to survey patient empowerment in patients with CHD. The Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale 10, based on the Swedish Diabetes Empowerment Scale 23, is a valid and reliable tool for assessing patient empowerment in patients with diabetes mellitus. The scale consists of four empowerment subscales: goal achievement, self-awareness, stress management and readiness to change. The Cronbach’s α-coefficient for the total Swedish Diabetes Empowerment Scale 23 ranged from 0.68 to 0.91 [28,29,30]. The Swedish Diabetes Empowerment Scale 10, a shortened version of the Swedish Diabetes Empowerment Scale 23, was also found to be reliable with the Cronbach’s α-coefficient value α = 0.84. After securing approval from the author of the scale, we replaced the word ‘diabetes’ with ‘coronary heart disease’. The Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale 10 has four subscales: 1) Goal achievement and overcoming barriers to goal achievement; 2) Self-awareness; 3) Managing stress; and 4) Assessing dissatisfaction and readiness to change. The items are scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). A higher value means a stronger patient empowerment [31]. Secondary outcomes were self-efficacy in general, [32] healthy diet, [33] and physical exercise [34, 35]. Self-efficacy was assessed using the General Self-efficacy Scale, which uses a four-point Likert scale ranging from not at all true (1) to exactly true (4). A higher score indicates a higher general self- efficacy. The General Self-efficacy Scale has been confirmed to be highly reliable, stable, and valid. The internal consistency of the scale was excellent with the Cronbach’s α-coefficient value α = 0.88 [36, 37]. Healthy diet was assessed using the Nutrition Self-efficacy Scale and physical exercise using the Physical Exercise Self-efficacy Scale, both which use a four-point Likert scale ranging from very uncertain (1) to very certain (4). A higher score indicates a higher Nutrition/Physical Exercise self-efficacy. The Nutrition Self-efficacy Scale and the Physical Exercise Self-efficacy Scale are assessed to be reliable and valid tools, with internal consistency values were α = 0.87 and 0.88 respectively [33]. Physical exercise was also assessed using Stages of Change Scale [34].Well-being [38] was assessed using the Cantril Ladder of Life, a single-item indicator with a ladder of steps numbered from zero at the bottom to 10 at the top. Zero means the worst possible life, and 10 the best. The patients also answer on which step they stood 1 year ago, one which step they stand at present and they are asked to predict on which step they will stand 1 year in the future. Cantril’s Ladder of Life is used in large populations and validity and test-retest coefficients of 0.70 have been reported [39]. This ladder has also been used in patients ≥65 years recovering from an acute coronary event [40]. The EuroQoL 5-dimensions scale, [41] is a reliable and valid tool for use in patients with CHD. The Cronbach’s α-coefficient value of the EuroQoL 5-dimensions scale indicated an acceptable internal consistency with a value of α = 0.73. Discriminative validity analyses have confirmed that this scale distinguished well between patient groups with a different age, gender, or educational level. Self-rated health was measured by a Visual Analogue Scale within the EuroQoL 5-dimensions scale. This scale makes scores of 0–100, with higher scores indicating a better overall quality of life [42]. The Visual analogue Scale is easy to administer and produce stable intraclass correlations score (0.79) showing acceptable reliability, and satisfactory validity in patients with acute coronary syndrome [43]. Blood pressure, BMI, waist size, and blood tests were used at follow-up to measure effects of self-care. Primary and all secondary outcome data were included in the intention-to-treat analysis, which means that [44] all randomised patients in the groups which they were randomly assigned to were included in the analysis, regardless from deviation from protocol.

Statistical analysis

Sample size justification

Sample size calculation was based on the estimation that patients with diabetes mellitus, also a life-long disease, who reported poor patient empowerment scored on average 3.0 of the Swedish Diabetes Empowerment Scale Those who scored 3.6 or more were considered reporting good patient empowerment [30]. The difference between those reporting poor and good patient empowerment (0.6) was considered as a clinically relevant estimation of effect size and has been used for sample size calculation. Accordingly, at a significance level of α = 0.05 and a power of 1-β = 0.80 this generated the required sample size in each group of at least 63 patients. We recruited 157 patients to compensate for withdrawals.

Primary analysis: intention-to-treat

The intention-to-treat analysis included patients who fulfilled all inclusion criteria. Missing values in the primary outcome The Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale 10 have been substituted by the typical mean for the sample. Continuous data are presented as means ±SD or as median and interquartile range. Between-group differences were tested using independent-sample Student’s t-test for numerical variables or Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal distributed variables. For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was used. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significant level of P ≤ 0.05. The data were analysed using SPSS (IBM® SPSS Statistics, Version 23).

Results

Patients

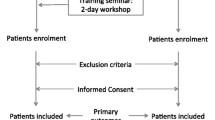

As presented in Fig. 1, all 157 patients were randomised and assigned to the problem-based learning intervention group (n = 79) or to home-sent patient information group (n = 78). No patient died during the study year. In the problem-based learning group, losses to one-year follow-up were due to missing the one-year visit (n = 32) and failure to submit questionnaires (n = 38). The patients participated in the problem-based learning intervention for a median of eight occasions of 13 (range 4–11). Seven patients did not attend the problem-based learning sessions but are included in the intention - to - treat analysis. Table 1, shows that there were no significant differences between the two study groups with respect to sociodemographic and clinical baseline characteristics.

Primary outcomes

Table 2 shows that patient empowerment as assessed with the Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale − 10 did not significantly differ between the problem-based learning group and the home-sent patient information group after 1 year.

Secondary outcomes

Table 2 shows that self-efficacy – assessed by The General Self-efficacy Scale, the Nutrition Self-efficacy Scale and the Physical Exercise Self-efficacy Scale – did not significantly differ between the problem-based learning group and the home-sent patient information group after 1 year. Well-being (assessed by the Cantril Ladder and EuroQoL 5-dimensions) and Self-rated Health (assessed by EuroQoL-Visual Analogue Scale) showed no significant differences between the problem-based learning group and the home-sent patient information group after 1 year. There were no differences between the groups regarding stages of change.

Table 3 shows that there was significant weight loss and therefore lower BMI in the problem-based learning group compared to the home-sent information group after 1 year. There was also a significant increase in HDL cholesterol favouring the problem-based learning group.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate patient education in primary care based on problem-based learning regarding patient empowerment and self-care in a cardiac population. Compared with home-sent patient information [24], adult learning theory [17] enacted as problem-based learning [22] did not improve patient empowerment [45]. Baseline data show that this group of patients were initially highly empowered compared to patients with diabetes mellitus or RA [30, 46]. Using problem-based learning in comparison with usual care to affect lifestyle changes in patients with RA showed small differences in mean values favouring problem-based learning intervention. The majority of the patients with RA scored that they had made lifestyle changes due to the problem-based programme [46]. Maybe, this positive effect is due to that patients with RA experience markedly physical health related problems and therefore the potential of feeling empowered by problem-based learning is higher compared to a population with CHD where symptoms of the disease is not always obvious. Our finding indicates that the potential for increasing patient empowerment is narrowed in our population.

Patient empowerment seems to be unexplored in cardiac rehabilitation. Findings that evaluate patient education in this context often focus on knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about cardiac disease, which indicate an intention to change a behaviour. For example, nurses’ individual patient education used motivational interviewing, which showed potential to alter patients’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about acute coronary syndrome [47]. However, when studying effects on behaviour change, knowledge is necessary but may not be enough. Effects of problem-based learning in hospital care concerning physical exercise in a cardiac population indicated that the patients could have exaggerated their self-reported activity. An activity monitor was used, which showed a lower level of physical activity compared to patient reported outcomes [48].

A systematic review [10] about nurses’ patient education after CHD supported that educational interventions increased patients’ knowledge and facilitated healthier dietary habits, smoking cessation and physical exercise. This review highlighted the need of a comprehensive patient education through individual- and group activities. We believe in accordance with this research [10] that patient education is not the same as telling people what to do or how to behave. Instead, patient education that is preferably coordinated by nurses [8] needs to be adjusted to the patients regarding beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, and motivation. This may be enhanced if patients gain more control over issues they themselves define as important [12], thus being empowered.

Strengths

In this study we tested a problem-based learning intervention [22], where the patients chose their own learning material according to own preferences and in line with the problems they discussed during the physical meetings in primary care. Problem-based learning was the foundation for the learning process, which was tested against the control group. The control group was informed by predetermined written patient information, based on a traditional model of information transferred to individuals [24]. In that way we compared the two pedagogical models.

We hypothesised that 1 year of problem-based patient education improves a patient’s self-efficacy, and patient empowerment to change self-care significantly compared to 1 year of standardised home-sent patient information. This study showed no effects on the Swedish-Coronary Empowerment Scale 10 that could be explained by the problem-based learning intervention. However, the problem-based learning intervention had a positive impact on secondary outcomes, weight loss and BMI. Also, the HDL cholesterol mean level was significantly increased after 1 year compared to the controls (i.e., home-sent patient information). These results are positively related to the problem-based learning group and should be interpreted cautiously as secondary outcomes have limited generalisability. Nonetheless, we interpret these results as an indication that a problem-based learning intervention provided by trained nurses may improve these risk factors after CHD when patients meet in groups in primary care. This result may also be due to that the problem-based learning intervention included consultations with physician and dietician, an offer that the controls were not given. When comparing our results with a review of patient education studies, [10] it can be stated that educational interventions significantly improve dietary and physical activity habits. However, it is not possible to conclude what intervention is most effective as most the interventions are poorly described. A strength of our study is that the intervention is thoroughly described [23]. To minimise large differences between usual care and the problem-based learning intervention, we offered the control group the similar information with parallel intervals as the experimental group. The controls had to have a pedagogical challenge so that problem-based learning was not tested against only usual care. We cannot guarantee that the controls read or used the written materials they were offered, and that is not the point with our study. Instead, we want to emphasise patients to take control of their own life and their recovery i.e. be empowered and manage their health. Another strength with this study is that the randomisation was well performed, and that the problem-based learning intervention group and the home-sent patient information group did not significantly differ regarding baseline characteristics.

Limitations

Despite that the COR-PRIM study was performed in accordance with the design article, [19] we acknowledge that the patients were highly selected in regard to patient empowerment and losses to follow-up were large. Of 446 eligible patients 35% (n = 157) consented to participate in the study, which may be considered as low. Reasons for declining participation included that the patients already felt empowered, so they did not believe they needed the intervention, which was quite demanding as the group discussions were scheduled for 1 year and there was a five-year follow-up. Problems with emphasising patients to join cardiac rehabilitation is not new [49]. Only 20–50% of eligible patients attend cardiac rehabilitation that could facilitate physical exercise and other effective preventive actions. Despite major efforts to increase the numbers of patients taking part in cardiac rehabilitating this has not improved in the last 20 years [50]. However, we believe that the patients who chose to be included in our study felt that they needed more support after hospital care. This indicate that joining peer-groups after CHD fills a place within cardiac rehabilitation [51, 52].

Conclusions

One-year of problem-based learning intervention in primary health care centres did not improve patient empowerment, self-efficacy, or well-being compared to home-sent patient information. A positive impact on weight loss, BMI, and HDL cholesterol was seen in the problem-based intervention group, indicating that pedagogically trained nurses in primary health care centres can facilitate groups of patients to improve their risk factors after an event of CHD.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and analyses made during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery by-pass surgery

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention.

References

Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Ž, Verschuren M, Albus C, Benlian P, Boysen G, Cifkova R, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33(13):1635–701.

Murray CL. Collaborators GCoD: Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390 North American Edition(10100):1151–210.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney M-T, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practiceThe Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–81.

Kotseva K, Wood D, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Ryden L, Jennings C, Gyberg V, Amouyel P, Bruthans J, Castro Conde A, et al. EUROASPIRE IV: a European society of cardiology survey on the lifestyle, risk, factor and therapeutic management of coronary patients from 24 European countries. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(6):636–48.

Dibben GO, Dalal HM, Taylor RS, Doherty P, Tang LH, Hillsdon M. Cardiac rehabilitation and physical activity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104(17):1394–402.

Nissen NK, Jónsdóttir M, Spindler H, Zwisler A-DO. Resistance to change: role of relationship and communal coping for coronary heart disease patients and their partners in making lifestyle changes. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(6):659–66.

Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. Eur Heart J. 2015:1163–U1188.

Snaterse M, Dobber J, Jepma P, Peters RJG, Ter Riet G, Boekholdt SM, Buurman BM. Reimer WJMSO: effective components of nurse-coordinated care to prevent recurrent coronary events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102:50–6.

Anderson L. Patient education in the management of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10.

GL de Melo G, Abdallah F, Grace SL, Thomas S, Oh P. Review: a systematic review of patient education in cardiac patients: do they increase knowledge and promote health behavior change? Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95:160–74.

WHO/Europe: Health 2020: the European policy for health and well-being -About Health 2020: Retrieved 2020-06-28 from https://www.euro.who.int/en/health topics/health-policy/health-2020-the-european-policy-for-health-and-well-being/about-health-2020.

Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: a concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):1923–39.

Orrego C, Ballester M, Perestelo L, Sunol R. Patient empowerment as a promising avenue towards health and social care integration: results from an overview of systematic reviews of patient empowerment interventions. Int J Integrated Care (IJIC). 2016;16(6):1–2.

Kärner A. Patients’ and spouses’ perspectives on coronary heart disease and its treatment. Medical Diss no 849. Linköping: Linköping University; 2004.

Köhler AK, Nilsson S, Jaarsma T, Tingström P. Health beliefs about lifestyle habits differ between patients and spouses 1 year after a cardiac event – a qualitative analysis based on the health belief model. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31(2):332–41.

Kelly M, McCarthy S, Sahm L. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of patients and carers regarding medication adherence: a review of qualitative literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:1423–31.

Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner. The definitive classic in adult education and human resourse development, 5th ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company; 1998.

Boud D, Feletti G. The challenge of problem-based learning. London: Kogan Page Ltd; 1997.

Kärner A, Nilsson S, T. J, Andersson A, Wiréhn A-B, Wodlin P, Hjelmfors L, Tingstrom P. The effect of problem-based learning in patient education after an event of CORONARY heart disease - a randomised study in PRIMARY health care: design and methodology of the COR-PRIM study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(110):1–9.

Abrandt Dahlgren A. Portraits of PBL. A cross-faculty comparison of Students' experiences of problem-based learning [thesis]. Linköping: Linköping University; 2001.

Biggs J. Teaching for quality at university. Ballmoor Buckingham: Open university press; 2003.

Engel C. Not just a method but a way of learning. In: the challenge of problem based-learning. Edited by Boud D, Feletti G. London: Kogan Page; 1991.

Williams B, Pace A. Problem based learning in chronic disease management: a review of the research. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:14–9.

Tang T, Funnel M, Brown M, Kurlander J. Self-management support in "real-world" settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:178–84.

Kärner Köhler A, Tingström P, Jaarsma T, Nilsson S. Patient empowerment and general self-efficacy in patients with coronary heart disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0749-y.

Matts JP, Lachin JM. Properties of permuted - block randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9:327–44.

Barrow H. Problembased learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. In: bringing problem-based learnin to higher education: theory and practice. Edited by Wilerson L, Gijselaers W. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1996.

Arvidsson S, Bergman S, Arvidsson B, Fridlund B, Tingström P. Psychometric properties of the Swedish rheumatic disease empowerment scale, SWE-RES-23. Musculoskeletal Care. 2012;10:101–9.

Barr P, Scholl I, Bravo P, Faber MJ, Elwyn G, McAllister M. Assessment of Patient Empowerment - A Systematic Review of Measures. PLoS One. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.phone.0126553.

Leksell J, Funnel M, Sandberg G, Smide B, Wiklund G, Wikblad K. Psychometric properties of the Swedish diabetes empowerment scale. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21:247–52.

Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, Funnell MM, Oh MS. The diabetes empowerment scale-short form (DES-SF). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1641–2.

Swedish version of the general self-efficacy scale. 1999. http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/swedish.htm. Accessed 4 Sept 2019.

Health-specific self-efficacy scales. 1999. http://www.RalfSchwarzer.de/. Accessed 4 Sept 2019.

Kamwendo K, Tingström P, Svensson E, Bergdahl B. The effect of problem based learning on stages of change for exercise behaviour in patients with coronary artery disease. Physiother Res Int. 2004;9(1):24–32.

Prochaska J, Redding C, Evers K. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Health behavior and health education - theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 99–120.

Leganger A, Kraft P, Roysamb E. Perceived self-efficacy in health behaviour research: conceptualisation, measurement and correlates. Psychol Health. 2000;15(1):51.

Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general Sel-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–57.

Cantril H. The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1965.

Andrews F, Withey S. Social indicators of well-being: American's perceptions of life quality. New York: Plenum; 1976.

Ståhle A, Mattsson E, Rydén L, Unden A-L, Nordlander R. Improved physical fitness and quality of life following training of elderly patients after acute coronary events. A 1 year follow-up randomized controlled study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(20):1475–84.

De Smedt D, Clays E, Doyle F, Kotseva K, Prugger C, Pająk A, Jennings C, Wood D, De Bacquer D. Validity and reliability of three commonly used quality of life measures in a large European population of coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):2294–9.

EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

Schweikert B, Hahmann H, Leidl R. Validation of the EuroQol questionnaire in cardiac rehabilitation. Heart. 2006;92(1):62–7.

Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: a review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(3):109–12.

Funnel M, Anderson R. Patient empowerment: a look back, a look ahead. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(3):454–62.

Arvidsson S, Bergman S, Arvidsson B, Fridlund B, Tingström P. Effects of a self-care promotion problem-based learning programme in people with rheumatic diseases: a randomized controlled study. J Adv Nurs. 2012;67(7):1500–14.

O’Brien F, McKee G, Mooney M, O’Donnell S, Moser D. Improving knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about acute coronary syndrome through an individualized educational intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(2):179–87.

Tingström PR, Ekelund U, Kamwendo K, Bergdahl B. Effects of a problem-based learning rehabilitation program on physical activity in patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiopulm Rehab Prev. 2006;26(1):32–8.

Giuliano C, Parmenter BJ, Baker MK, Mitchell BL, Williams AD, Lyndon K, Mair T, Maiorana A, Smart NA, Levinger I. Cardiac rehabilitation for patients with coronary artery disease: a practical guide to enhance patient outcomes through continuity of care. Clin Med Insights: Cardiol. 2017;11:1–7.

Jelinek M, Thomson D, Ski C, Bunker S, Vale M. 40 years of cardicac rehabilitation and secondary prevention in post-cardiac ischaemic patients. Are we still in the wilderness? Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:153–9.

Hildingh C, Fridlund B. A 3-year follow-up of participation in peer support groups after a cardiac event. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;3:315–20.

Junehag L, Asplund K, Svedlund M. A qualitative study: perceptions of the psychosocial consequences and access to support after an acute myocardial infarction. Int Crit Care Nurs. 2014;30:22–30.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Roland Carlstein, research partner from the Swedish Heart and Lung Association, for valuable advice in this study and Lars Valter for supporting the statistical analysis. We also gratefully acknowledge staff from the Vrinnevi Hospital in Norrköping and the primary care settings in south-eastern Östergötland involved in the study for invaluable collaboration. We would especially like to thank Anneli Rudenäs, Tina Ednarsson, Melina Appel and Victoria Grönlund who tutored the patient education and managed the follow-up.

Author details

AKK is a nurse and associate professor and TJ is a nurse and professor. PT is a nurse and associate professor and SN is a general practitioner and associate professor. All authors work at the Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden. SN works clinically at Primary Health Care Centre, in Vikbolandet, 610 24 Vikbolandet, Sweden.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swedish Heart and Lung Association, project numbers [E091/10, E122/11, E083/12, and E103/13] and The County Council Region Östergötland, Sweden, project numbers [LIO-92281, − 125151, − 27535, − 354951, and LIO- 433801]. There was no role of the funding body in the study design, and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AKK, SN, TJ, PT contributed to the conception or design of the work. AKK contributed to the acquisition and together with TJ, PT and SN to the analysis and interpretation for the work. AKK drafted the manuscript in collaboration with PT and SN. All authors critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping, c/o Faculty of Health Sciences, SE-58185 Linköping, Sweden. Reference number: 2010/128–31. Consent obtained from the participants was written.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Köhler, A.K., Jaarsma, T., Tingström, P. et al. The effect of problem-based learning after coronary heart disease – a randomised study in primary health care (COR-PRIM). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 20, 370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01647-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01647-2