Abstract

Background

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited myocardial disease characterized by fibrofatty replacement and ventricular arrhythmias. ARVC is believed to be a disease of the young, with most cases being diagnosed before the age of 40 years. We report here a case of newly diagnosed ARVC in an octogenarian associated with a pathogenic variant in the plakophilin 2 gene (PKP2).

Case presentation

An 80-year-old Japanese man was referred for sustained ventricular tachycardia. His baseline electrocardiogram showed negative T waves in V1–V4. Right ventriculography showed right ventricular aneurysm. Because this case met three major criteria, ARVC was diagnosed. He was successfully treated with radiofrequency ablation and oral amiodarone. Genetic analysis identified an insertion mutation in exon 8 of PKP2 (1725_1728dupGATG), which caused a frameshift and premature termination of translation (R577DfsX5).

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of newly diagnosed ARVC in an octogenarian associated with a loss-of-function PKP2 pathogenic variant. Although the late clinical presentation of ARVC is rare, it should be included in the differential diagnosis when treating older patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited myocardial disease characterized by fibrofatty replacement and ventricular arrhythmias [1]. ARVC is believed to be a disease of the young, with most cases being diagnosed before the age of 40 years [2]. We report here a case of newly diagnosed ARVC in an octogenarian associated with a pathogenic variant in the plakophilin 2 gene (PKP2).

Case presentation

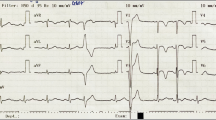

An 80-year-old Japanese man with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department for left shoulder pain. Although he was alert and conscious, his systolic blood pressure was 80 mmHg and his pulse was 204 beats/minute. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG; Fig. 1a) showed ventricular tachycardia (VT). Electrical cardioversion was required because intravenous amiodarone failed to terminate the VT. His baseline ECG 1 month prior to this admission (Fig. 1b), which was recorded during hospitalization for appendicitis in another center, showed negative T waves in V1–V4 (Fig. 1b). Two-dimensional echocardiography showed normal left ventricular wall motion but severely reduced wall motion throughout the right ventricle. The right ventricular outflow tract was dilated on both the parasternal long (33 mm) and short (40 mm) axes and the right ventricular fractional area change was 26.2%. Coronary angiography was normal, but right ventriculography showed a right ventricular aneurysm (Fig. 2a, Additional file 1: Movie 1). The patient had no history of recent endurance exercise or participation in sports. Furthermore, a detailed family history revealed no cases of ARVC or sudden cardiac death. Although the patient didn’t give consent to endomyocardial biopsy, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging suggested diffuse areas of fat tissue in the right ventricular wall and also revealed late gadolinium enhancement in both right and left ventricular walls (Additional file 2).

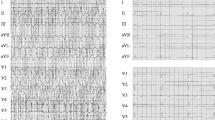

a Right anterior oblique (RAO) view of right ventriculography showing a right ventricular aneurysm (arrowheads). b RAO view of a right ventricular bipolar voltage map. Red areas represent dense scarring (amplitude < 0.5 mV). Areas with a color gradient between red and purple represent the border zone (amplitude of 0.5–1.5 mV). c Alignment of cDNA in the vicinity of codon 1725. The insertion mutation causes a frameshift and premature termination of translation (R577DfsX5)

Additional file 1: Movie 1. RAO view of right ventriculography showing a right ventricular aneurysm. (AVI 17715 kb)

Because this case met three major criteria (right ventricular aneurysm, inverted T waves in right precordial leads, and VT of left bundle-branch morphology with a superior axis), a clinical diagnosis of definite ARVC was established [3]. Regarding differential diagnosis, we considered cardiac sarcoidosis which can mimic ARVC. Although 18F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission scanning can be positive in some ARVC cases [4], cardiac sarcoidosis was deemed unlikely because abnormal FDG uptake was not observed in this patient (Additional file 3).

We recommended an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; however, the patient rejected this suggestion and underwent an electrophysiological study and catheter ablation. A three-dimensional electroanatomical voltage map (Carto, Biosense-Webster Inc., CA, USA; Fig. 2b) during sinus rhythm showed an extensive low voltage zone in the right ventricle. Linear ablation along the low voltage zones with the pace mapping technique was performed. We then continued oral administration of amiodarone. The patient has been followed up for 3 years without recurrence of VT.

Genetic analysis identified a GATG duplication in exon 8 of PKP2 (1725_1728dupGATG), which causes a frameshift and subsequent premature termination of translation (R577DfsX5) (Fig. 2c). The variant was not identified in the patient’s two daughters (51 and 49 years old) and is unknown in his parents because they are both deceased. Although this pathogenic variant is not reported in the genome aggregation database (gnomAD), previous reports have described this variant in Japanese ARVC patients [5, 6].

Discussion

Current Task Force Criteria for an ARVC diagnosis combine diagnostic criteria from six categories including 1) global or regional dysfunction and structural alterations, 2) tissue characterization of the wall, 3) repolarization abnormalities, 4) depolarization/conduction abnormalities, 5) arrhythmias, and 6) family history [3]. This case met four major criteria so a diagnosis of definite ARVC was established.

Gerull and colleagues previously reported that pathogenic variants in PKP2, encoding the desmosomal protein plakophilin 2, are associated with ARVC [7]. Desmosomes are multiprotein structures of the cell membrane, which provide strong adhesion between cells. Armadillo-repeat proteins, as well as desmosomal cadherins and plakins, are known as structural constituents of desmosomes. Plakophilin 2 is a desmosomal armadillo-repeat protein, linking desmosomal cadherins with desmoplakin and the intermediate filament system [7]. Pathogenic variants of this gene are present in one-quarter of definite Japanese ARVC [6] and nearly half of Western European ARVC patients [8, 9].

A recent study of 502 ARVC patients revealed that 104 (21%) had a late presentation (age ≥ 50 years at diagnosis) and 3% were ≥ 65 years at diagnosis with a mean age of 71 years (range, 65–76 years) [10]. Interestingly, late presentation of symptoms did not necessarily indicate a low risk for disease-related morbidity and mortality, but showed a similar arrhythmic time course as that for earlier onset symptoms. Late presentation was reportedly associated with male sex, pathogenic variant, right ventricular structural disease, lack of family history, and electrophysiological study inducibility [10]. The present case shared four of these characteristics (male sex, pathogenic variant, right ventricular structural disease, and lack of family history). Limitations of our report include the possibility that ARVC was missed on prior examination. Nevertheless, a detailed interview revealed no previous arrhythmia history. We also requested ECG reports from local hospitals including information from medical checkups; however, none were obtained. Regardless of this, our findings reveal important characteristics of ARVC with late presentation.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of newly diagnosed ARVC with a PKP2 pathogenic variant in an octogenarian. Although the late clinical presentation of ARVC is rare, it should be included in the differential diagnosis when treating older patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

Abbreviations

- ARVC:

-

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- FDG:

-

18F fluorodeoxyglucose

- gnomAD:

-

Genome aggregation database

- LGE:

-

Late gadolinium enhancement

- LV:

-

Left ventricle

- PKP2:

-

Plakophilin 2

- RAO:

-

Right anterior oblique

- RV:

-

Right ventricle

- T1BB:

-

T1-weighted black-blood

- VT:

-

Ventricular tachycardia

References

Basso C, Corrado D, Marcus FI, Nava A, Thiene G. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2009;373(9671):1289–300.

Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Guiraudon G, Frank R, Laurenceau JL, Malergue C, Grosgogeat Y. Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases. Circulation. 1982;65(2):384–98.

Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation. 2010;121(13):1533–41.

Protonotarios A, Wicks E, Ashworth M, Stephenson E, Guttmann O, Savvatis K, Sekhri N, Mohiddin SA, Syrris P, Menezes L, et al. Prevalence of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography abnormalities in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2018;(18)34604-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.083. [Epub ahead of print]

Nagaoka I, Matsui K, Ueyama T, Kanemoto M, Wu J, Shimizu A, Matsuzaki M, Horie M. Novel mutation of plakophilin-2 associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2006;70(7):933–5.

Wada Y, Ohno S, Aiba T, Horie M. Unique genetic background and outcome of non-Caucasian Japanese probands with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5(6):639–51.

Gerull B, Heuser A, Wichter T, Paul M, Basson CT, McDermott DA, Lerman BB, Markowitz SM, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA, et al. Mutations in the desmosomal protein plakophilin-2 are common in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 2004;36(11):1162–4.

van Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, Jongbloed R, Wiesfeld AC, Wilde AA, van der Smagt J, Boven LG, Mannens MM, van Langen IM, et al. Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1650–8.

Cox MG, van der Zwaag PA, van der Werf C, van der Smagt JJ, Noorman M, Bhuiyan ZA, Wiesfeld AC, Volders PG, van Langen IM, Atsma DE, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: pathogenic desmosome mutations in index-patients predict outcome of family screening: Dutch arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy genotype-phenotype follow-up study. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2690–700.

Bhonsale A, Te Riele A, Sawant AC, Groeneweg JA, James CA, Murray B, Tichnell C, Mast TP, van der Pols MJ, Cramer MJM, et al. Cardiac phenotype and long-term prognosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia patients with late presentation. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(6):883–91.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen Knapp, PhD for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YA designed the study and drafted the manuscript. YA, TH, TM, and HF evaluated and treated the patient. YW and MH performed the genetic analysis. YY analyzed and interpreted cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. KS, MH, and SM participated in the manuscript revision process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 2:

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. a. T1-weighted black-blood (T1BB) imaging of a short axis view indicating diffuse areas of fat tissue in the right ventricular wall (yellow arrows). b. T1BB imaging with fat saturation (fat-sat) of a short axis view at the same level as the T1BB imaging (panel a). c. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in the right ventricular wall in a short axis view (red arrows). d. Late gadolinium enhancement in the mid-wall of the interventricular septum in a short axis view (red arrows). (TIFF 5156 kb)

Additional file 3:

18F fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) with computed tomography (CT) a A transverse view of FDG-PET/CT. b. A coronal view of FDG-PET/CT. Abnormal FDG uptake was not detected in left ventricle (LV) or right ventricle (RV). (TIFF 4263 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Adachi, Y., Hayashi, T., Mitsuhashi, T. et al. Late presentation of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in an octogenarian associated with a pathogenic variant in the plakophilin 2 gene: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 19, 41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1018-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1018-2