Abstract

Background

Everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) represent an innovative treatment option for coronary artery disease. Clinical and angiographic results seem promising, however, data on its immediate procedural performance are still scarce. The aim of our study was to assess the mechanical properties of BVS by Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in clinical routine.

Methods

Post-implantation OCT images of 40 BVS were retrospectively compared to those of 40 metallic everolimus-eluting stents (EES). Post-procedural device related morphological features were assessed. This included incidences of gross underexpansion and the stent eccentricity index (SEI, minimum/maximum diameter) as a measure for focal radial strength.

Results

Patients receiving BVS were younger than those with EES (54.0 ± 11.2 years versus 61.7 ± 11.4 years, p = 0.012), the remaining baseline, vessel and lesion characteristics were comparable between groups. Lesion pre-dilatation was more frequently performed and inflation time was longer in the BVS than in the EES group (n = 34 versus n = 23, p = 0.006 and 44.2 ± 12.8 versus 25.6 ± 8.4 seconds, p < 0.001, respectively). There were no significant differences in maximal inflation pressures and post-dilatation frequencies with non-compliant balloons between groups. Whereas gross device underexpansion was not significantly different, SEI was significantly lower in the BVS group (n = 12 (30 %) versus n = 14 (35 %), p = 0.812 and 0.69 ± 0.08 versus 0.76 ± 0.09, p < 0.001, respectively). There was no difference in major adverse cardiac event-rate at six months.

Conclusion

Our data show that focal radial expansion was significantly reduced in BVS compared to EES in a clinical routine setting using no routine post-dilatation protocol. Whether these findings have impact on scaffold mid-term results as well as on clinical outcome has to be investigated in larger, randomized trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drug eluting stents (DES) have shown to be highly effective in the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease [1–3] as neointimal hyperplasia after a vascular injury was reduced compared to when bare metal stents were used [2, 3]. Nevertheless, delayed or absent strut endothelialization, persistent or acquired malapposition and neoatherosclerosis of DES contribute to late stent failure rates which are in the range of 1-2 % a year within the first three years after implantation [4–6]. In addition stent fractures especially at hinge points of the coronary vessels and the lack of adaptive remodelling processes in the artery wall can contribute to late events.

Bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) were developed in order to reduce those potential adverse events after a coronary intervention. After the bioresorption process is completed there will not be any potential triggers for late adverse events [7]. In contrast to vessels caged by metallic stents, vessels transiently scaffolded by bioresorbable materials are able to perform vasoconstriction and vasodilation and therefore could also contribute to better symptom control in patients with coronary artery disease [8–11]. It was also shown that BVS are characterized by a better conformability to the vessel compared to metallic stents [12]. On the other hand it is still unclear if the radial strength provided by BVS is sufficient throughout various clinical scenarios. It has been shown that metallic stents generate a larger acute lumen gain compared to BVS, but scaffold/stent type was not predictive for acute recoil [13]. Intravascular imaging data describing device strength and expansion are still scarce. The aim of the present study was to assess the mechanical properties of BVS by Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in clinical routine.

Methods

Patients

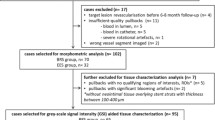

Between March and June 2013, 26 consecutive patients underwent OCT immediately after implantation of 40 BVS (Absorb, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Elective patients as well as patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) were included. The OCT data of these patients were retrospectively compared with those of 34 consecutive patients after implantation of 40 metallic everolimus-eluting stents (EES, Xience, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Patient characteristics were collected from the medical records of each patient, device characteristics and deployment strategies were collected from the database of the cardiac catheter laboratory. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna and all patients gave their written informed consent.

Definitions

Stent eccentricity index (SEI): at the site of minimal lumen area (MLA) stent eccentricity index, defined as the ratio between minimal and maximal diameter, was calculated [14].

Stent symmetry index (SSI): at the site of MLA stent symmetry index, defined as (maximal-minimal diameter)/maximal diameter, was calculated [14].

Underexpansion: a stent was considered underexpanded if MLA was ≤ 80 % of average reference lumen area [15].

Plaque characteristics: plaque type was determined at proximal and distal stent ending, as well as at MLA and was considered to be either lipid-rich, fibrous or fibro-calcific [16].

Incomplete stent apposition (ISA): struts were considered incompletely apposed when they were separated from the underlying vessel wall in case of BVS [17] or when the axial distance between strut's surface and the luminal surface was greater than the strut thickness in case of EES [18].

OCT - acquisition and analysis

Patients were pre-treated with a dual antiplatelet therapy, a weight-adjusted intravenous bolus of unfractionated heparin, and 200 μg intracoronary nitroglycerine. The OCT images were obtained using a frequency domain (FD) - OCT system (LightLab Imaging, Inc., Westford, MS, USA). The FD-OCT imaging catheters were delivered over a 0.014-inch (0.0356 cm) guide wire through a 6-F guiding catheter. Images were acquired using a motorized pullback system at a speed of 36 mm/s during a flush of 4 to 6 ml/s of iso-osmolar contrast (Iodixanol 320, VisipaqueTM, GE Health Care, Cork, Ireland) through the guiding catheter to replace the blood flow and permit the visualization of the stented segment and intima-lumen interface. Whenever the stented segment was too long to be completely imaged in a single pullback, the image acquisition was repeated from the same position during a second contrast injection. Anatomic landmarks such as side branches, calcifications or stent overlap segments were used for longitudinal view orientation.

OCT imaging was performed after what was deemed to be an angiographically successful intervention at the operator’s discretion. All OCT frames were digitally stored and independently analyzed using an offline software (LightLab Console) by one operator, who is experienced in and familiar with assessing OCT images. Cross-sections within the stented segment were analyzed every frame.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS® Statistics 21.0 (SPSS Inc, Chigago, USA). Quantitative data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative data were presented as frequencies. Categorical variables were assessed by χ2 statistics and Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared using an unpaired t-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients receiving BVS were younger than those with EES (54.0 ± 11.2 years vs. 61.7 ± 11.4 years, p = 0.012) and were smokers less frequently. The remaining baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). The majority of treated lesions in both groups were simple lesions (type B1, 62 % in BVS vs. 70 % in EES group, p = 0.407).

Device and procedural characteristics are depicted in Table 2. Pre-dilatation was more frequently performed before BVS implantation and the diameter of the pre-dilatation balloon was larger in the BVS group (85 % vs. 58 %, p = 0.006 and 2.64 ± 0.51 mm vs. 2.34 ± 0.46 mm, p = 0.026, respectively), while BVS diameters were larger compared to those of EES (3.23 ± 0.34 mm vs. 3.07 ± 0.54 mm, p = 0.124). Lesion diameter stenosis was less severe in the BVS group and the inflation time was longer (81 ± 14 % vs. 89 ± 14 %, p = 0.023 and 44 ± 13 sec vs. 26 ± 8 sec, p < 0.001, respectively).

OCT results

OCT analysis (Table 3) showed comparable plaque compositions between the two groups at the proximal and distal stent endings as well as at the point of minimal lumen area. Although there were no statistically significant differences in the minimal lumen area and in the incidence of device underexpansion between the groups (6.38 ± 2.00 mm2 vs. 6.42 ± 2.42 mm2, p = 0.662 and 30 % vs. 35 %, p = 0.812, respectively) the SEI at the site of the minimal lumen area was significantly lower in the BVS group compared to EES (0.69 ± 0.08 vs. 0.76 ± 0.09, p < 0.001). SSI was significantly higher in BVS compared to EES (0.30 ± 0.09 vs. 0.23 ± 0.09, p < 0.001).

Clinical follow-up

After six months there was no detectable difference in major adverse cardiac event (MACE) rate between groups (Table 4). One patient in the BVS group underwent angiography after three months because of recurrent angina. Subacute thrombotic lesions were angiographically revealed and thrombus aspiration following dilatation with a non-compliant balloon was performed. One patient in the EES group was re-admitted due to unstable angina after 45 days. Angiography showed an intima-flap at the proximal stent ending which resulted in another overlapping stent-implantation. Another EES patient underwent elective angiography after three months. Although he presented free of any symptoms EES showed significant in-stent-restenosis which was fixed by drug-eluting balloon dilatation.

Discussion

Whereas BVS were rapidly adopted in clinical routine, prospective data especially with regard to complex lesions are still rare [19–21]. Recent data suggest that acute and late stent thrombosis are more frequent in BVS compared to DES [22], which is potentially associated with the unique mechanical properties of BVS. It has been shown that OCT is a valuable tool in determining post-procedural success with both BVS and DES as it potentially reduces late complications caused by mechanical shortcomings of the devices not detected when using angiography. This is the first OCT study comparing BVS and EES in a clinical routine setting.

The main finding of this study was that in a routine setting using no post-dilatation protocol, although gross device expansion of BVS and EES was comparable, device expansion uniformity of BVS, defined by SEI at the point of MLA, was significantly lower, whereas SSI was higher in BVS compared to EES (Fig. 1).

This lower device expansion can potentially contribute to an alteration in blood flow dynamics and can therefore represent a source for acute and subacute post-procedural complications as shown by Otake and coworkers [23]. Interestingly, this finding contradicts the study of Mattesini [14] but is in line with that of Brugaletta and coworkers in a substudy of the Absorb cohort B trial [24]. The most plausible explanation is that in the study of Mattesini a more aggressive vessel preparation with a balloon/artery ratio 1:1 and a stringent OCT guided post-dilatation balloon inflation strategy with non-compliant balloons were performed. In our study pre-dilatation was performed with in average 0.5 mm undersized balloons in 85 % of all cases and post-dilatation with NC-balloons was done only in 55 % of BVS implantations which is closer to the treatment procedure used in in the Absorb cohort B trial. Accordingly post-dilatation was performed in only 50 % of cases in the Ghost-EU trial, which included 1189 patients [25]. It is noteworthy that especially in the early phase the incidences of scaffold thrombosis were more frequent than anticipated in this study, which may be influenced by the low rates of post-dilatation (<40 %) in these patients with BVS failure. Although the lack of a stringent post-dilatation protocol is the most plausible cause for the discussed differences in SEI other contributing factors have to be considered. In contrast to our study, in which patients with ACS represented > 1/3 of the study population, they were not included in the study of Mattesini. In patients presenting with ACS, previous imaging analysis found more complex lesion morphologies when compared to patients with stable CAD [26]: Especially developing intramural hemorrhages is more common in acute lesions and because of the limited radial strength of BVS [13] they might not be able to withstand the consecutively increased vessel wall resistance (Fig. 2). The different post-procedural stent geometry was also supported by significant differences in the nominal vessel/proximal device ending diameter, where the proximal BVS ending was in average smaller and the proximal EES was in average larger than the native vessel diameter. This finding is in accordance with the study of Mattesini, where ISA at the proximal edge was more frequently observed in the BVS group. Although the clinical significance of ISA is not definitely determined, it has been associated with stent thrombosis in IVUS studies [27, 28]. In addition protruding struts at the proximal edge may complicate the advancement of other devices distal of the stent. However compared to DES the bioabsorbable technology has the potential advantage of ISA being at least only a temporary problem.

Limitations

This is a retrospective, single center, non-randomized observational study in a limited number of patients. Although patient characteristics were well matched no propensity adjustments have been performed. Final OCT assessment was performed, when the operators deemed to be angiographically successful, which provides a potential bias.

Nevertheless in the learning curve of a new technology it is of high value to identify potential safety concerns additionally to large randomized trials in clinical studies. In our routine setting we could reveal significant differences in the post-procedural geometry between BVS and EES using OCT. Whether these differences may contribute to the somewhat higher stent thrombosis rates observed in other series remains unclear. To avoid inappropriate BVS expansion it seems advisable to incorporate routine post-dilatation with NC-balloons in the procedural protocol. The role of aggressive pre-dilatation with its potential complications remains a matter of debate and the use of intravascular imaging may further delineate the appropriate use of BVS.

Conclusion

Although minimal lumen areas and rates of device underexpansion were comparable between BVS and EES, local radial expansion is significantly reduced in BVS in a clinical routine setting using no post-dilatation protocol. The clinical importance of this finding remains unclear and has to be evaluated in larger, randomized trials. However, a lower uniform expansion of the BVS could contribute to clinical events such as scaffold thrombosis and should be considered when implanting these devices. Considering the relatively low number of post-dilatations with non-compliant balloons in the BVS group our data further suggest that routine post-dilatation should be strongly considered.

Abbreviations

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BVS, bioresorbable vascular scaffold; CAD, coronary artery disease; DES, drug eluting stent; EES; everolimus eluting stent; FD, frequency domain; ISA, incomplete stent apposition; IVUS, intra vascular ultra sound, MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MLA, minimal lumen area; NC, non compliant; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SEI, stent eccentricity index; SSI, stent symmetry index.

References

Grube E, Dawkins K, Guagliumi G, Banning A, Zmudka K, Colombo A, Thuesen L, Hauptman K, Marco J, Wijns W, Joshi A, Mascioli S. TAXUS VI final 5-year results: a multicentre, randomised trial comparing polymer-based moderate-release paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent for treatment of long, complex coronary artery lesions. EuroIntervention. 2009;4:572–7.

Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O'Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE. SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–23.

Stettler C, Wandel S, Allemann S, Kastrati A, Morice MC, Schörnig A, Pfisterer ME, Stone GW, Leon MB, de Lezo JS, Goy JJ, Park SJ, Sabaté M, Suttorp MJ, Kelbaek H, Spaulding C, Menichelli M, Vermeersch P, Dirksen MT, Cervinka P, Petronio AS, Nordmann AJ, Diem P, Meier B, Zwahlen M, Reichenbach S, Trelle S, Windecker S, Jüni P. Outcomes associated with drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: a collaborative network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:937–48.

Cook S, Wenaweser P, Togni M, Billinger M, Morger C, Seiler C, Vogel R, Hess O, Meier B, Windecker S. Incomplete stent apposition and very late stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2007;115:2426–34.

Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, Abrecht L, Vaina S, Morger C, Kukreja N, Jüni P, Sianos G, Hellige G, van Domburg RT, Hess OM, Boersma E, Meier B, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667–78.

Gutierrez-Chico JL, Regar E, Nuesch E, Okamura T, Wykrzykowska J, di Mario C, Windecker S, van Es GA, Gobbens P, Jüni P, Serruys PW. Delayed coverage in malapposed and side-branch struts with respect to well-apposed struts in drug-eluting stents: in vivo assessment with optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2011;124:612–23.

Serruys PW, Garcia-Garcia HM, Onuma Y. From metallic cages to transient bioresorbable scaffolds: change in paradigm of coronary revascularization in the upcoming decade? Eur Heart J. 2001;33:16–25b.

Maier W, Windecker S, Küng A, Lütolf R, Eberli FR, Meier B, Hess OM. Exercise-induced coronary artery vasodilation is not impaired by stent placement. Circulation. 2002;105:2373–7.

Ormiston JA, Serruys PW, Onuma Y, van Geuns RJ, de Bruyne B, Dudek D, Thuesen L, Smits PC, Chevalier B, McClean D, Koolen J, Windecker S, Whitbourn R, Meredith I, Dorange C, Veldhof S, Hebert KM, Rapoza R, Garcia-Garcia HM . First serial assessment at 6 months and 2 years of the second generation of absorb everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold: a multi-imaging modality study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:620–32.

Serruys PW, Onuma Y, Ormiston JA, de Bruyne B, Regar E, Dudek D, Thuesen L, Smits PC, Chevalier B, McClean D, Koolen J, Windecker S, Whitbourn R, Meredith I, Dorange C, Veldhof S, Miquel-Hebert K, Rapoza R, Garcia-Garcia HM. Evaluation of the second generation of a bioresorbable everolimus drug-eluting vascular scaffold for treatment of de novo coronary artery stenosis: six-month clinical and imaging outcomes. Circulation. 2010;122:2301–12.

Serruys PW, Ormiston JA, Onuma Y, Regar E, Gonzalo N, Garcia-Garcia HM, Nieman K, Bruining N, Dorange C, Miquel-Hebert K, Veldhof S, Webster M, Thuesen L, Dudek D. A bioabsorbable everolimus-eluting coronary stent system (ABSORB): 2-year outcomes and results from multiple imaging methods. Lancet. 2009;373:897–910.

Gomez-Lara J, Garcia-Garcia HM, Onuma Y, Garg S, Regar E, de Bruyne B, Windecker S, McClean D, Thuesen L, Dudek D, Koolen J, Whitbourn R, Smits PC, Chevalier B, Dorange C, Veldhof S, Morel MA, de Vries T, Ormiston JA. Serruys PW (2010) A comparison of the conformability of everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffolds to metal platform coronary stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:1190–8.

Onuma Y, Serruys PW, Gomez J, de Bruyne B, Dudek D, Thuesen L, Smits P, Chevalier B, McClean D, Koolen J, Windecker S, Whitbourn R, Meredith I, Garcia-Garcia H, Ormiston JA. ABSORB cohort a and b investigators. comparison of in vivo acute stent recoil between the bioresorbable everolimus-eluting coronary scaffolds (revision 1.0 and 1.1) and the metallic everolimus-eluting stent. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78:3–12.

Mattesini A, Secco GG, Dall'Ara G, Ghione M, Rama-Merchan JC, Lupi A, Viceconte N, Lindsay AC, De Silva R, Foin N, Naganuma T, Valente S, Colombo A, Di Mario C. ABSORB biodegradable stents versus second-generation metal stents: a comparison study of 100 complex lesions treated under OCT guidance. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:741–50.

de Jaegere P, Mudra H, Figulla H, Almagor Y, Doucet S, Penn I, Colombo A, Hamm C, Bartorelli A, Rothman M, Nobuyoshi M, Yamaguchi T, Voudris V, Di Mario C, Makovski S, Hausmann D, Rowe S, Rabinovich S, Sunamura M, van Es GA. Intravascular ultrasound-guided optimized stent deployment. Immediate and 6 months clincal and angiographic results from the multicenter ultrasound stenting in coronaries study (MUSIC Study). Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1214–23.

Yabushita H, Bouma BE, Houser SL, Aretz HT, Jang IK, Schlendorf KH, Kauffman CR, Shishkov M, Kang DH, Halpern EF, Tearney GJ. Characterization of human atherosclerosis by optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2002;106:1640–5.

Tearney GJ, Regar E, Akasaka T, Adriaenssens T, Barlis P, Bezerra HG, Bouma B, Bruining N, Cho JM, Chowdhary S, Costa MA, de Silva R, Dijkstra J, Di Mario C, Dudek D, Falk E, Feldman MD, Fitzgerald P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Gonzalo N, Granada JF, Guagliumi G, Holm NR, Honda Y, Ikeno F, Kawasaki M, Kochman J, Koltowski L, Kubo T, Kume T, Kyono H, Lam CC, Lamouche G, Lee DP, Leon MB, Maehara A, Manfrini O, Mintz GS, Mizuno K, Morel MA, Nadkarni S, Okura H, Otake H, Pietrasik A, Prati F, Räber L, Radu MD, Rieber J, Riga M, Rollins A, Rosenberg M, Sirbu V, Serruys PW, Shimada K, Shinke T, Shite J, Siegel E, Sonoda S, Suter M, Takarada S, Tanaka A, Terashima M, Thim T, Uemura S, Ughi GJ, van Beusekom HM, van der Steen AF, van Es GA, van Soest G, Virmani R, Waxman S, Weissman NJ, Weisz G. International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography (IWG-IVOCT). Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: a report from the international working group for intravascular optical coherence tomography standardization and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1058–72.

Barlis P, Dimopoulos K, Tanigawa J, Dzielicka E, Ferrante G, Del Furia F, Di Mario C. Quantitative analysis of intracoronary optical coherence tomography measurments of stent strut apposition and tissue coverage. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141:151–6.

Sato K, Latib A, Panoulas VF, Kawamoto H, Naganuma T, Miyazaki T, Colombo A. Procedural feasibility and clinical outcomes in propensity-matched patients treated with bioresorbable scaffolds vs. new-generation drug-eluting stents. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:328–34.

Biscaglia S, Campo G, Tebaldi M, Tumscitz C, Pavasini R, Fileti L, Secco GG, Di Mario C, Ferrari R. Bioresorbable vascular scaffold overlap evaluation with optical coherence tomography after implantation with or without enhanced stent visualization system (WOLFIE study): a two-centre prospective comparison. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:211–23.

Biscaglia S, Ugo F, Ielasi A, Secco GG, Durante A, D'Ascenzo F, Cerrato E, Balghith M, Pasquetto G, Penzo C, Fineschi M, Bonechi F, Templin C, Menozzi M, Aquilina M, Rognoni A, Capasso P, Di Mario C, Brugaletta S, Campo G. Bioresorbable scaffold vs. second generation drug eluting stent in long coronary lesions requiring overlap: a propensity-matched comparison (the UNDERDOGS study). Int J Cardiol. 2016;208:40–5.

Lipinski MJ, Escarcega RO, Baker NC, Benn HA, Gaglia MA, Torguson R, Waksman R. Scaffold thrombosis after percutaneous coronary intervention with ABSORB bioresorbable vascular scaffold: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:12–24.

Otake H, Shite J, Ako J, Shinke T, Tanino Y, Ogasawara D, Sawada T, Miyoshi N, Kato H, Koo BK, Honda Y, Fitzgerald PJ, Hirata K. Local determinants of thrombus formation following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation assessed by optical coherence tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:459–66.

Brugaletta S, Gomez-Lara J, Diletti R, Farooq V, van Geuns RJ, de Bruyne B, Dudek D, Garcia-Garcia HM, Ormiston JA, Serruys PW. Comparison of in vivo eccentricity and symmetry indices between metallic stents and bioresorbable vascular scaffolds: insights from the ABSORB and SPIRIT trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79:219–28.

Capodanno D, Gori T, Nef H, Latib A, Mehili J, Lesiak M, Caramanno G, Naber C, Di Mario C, Colombo A, Capranzano P, Wiebe J, Araszkiewicz A, Geraci S, Pyxaras S, Mattesini A, Naganuma T, Münzel T, Tamburino C Percutaneous coronary intervention with everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffolds in routine clinical practice: early and midterm outcomes from the European multicentre GHOST-EU registry. EuroIntervention. 2015;10:1144–53.

Reith S, Battermann S, Hoffmann R, Marx N, Burgmaier M. Optical coherence tomography derived differences of plaque characteristics in coronary culprit lesions between type 2 diabetic patients with and without acute coronary syndrome. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84:700–7.

Cheneau E, Leborgne L, Mintz GS, Kotani J, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Canos D, Castagna M, Weissman NJ, Waksman R. Predictors of subacute stent thrombosis: results of a systematic intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2003;108:43–7.

Fujii K, Carlier SG, Mintz GS, Yang YM, Moussa I, Weisz G, Dangas G, Mehran R, Lansky AJ, Kreps EM, Collins M, Stone GW, Moses JW, Leon MB. Stent underexpansion and residual reference segment stenosis are related to stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:995–8.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data cannot be shared due to current calculations regarding additional projects.

Authors’s contributions

DD, MD Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, approval of the final version. CG, MD Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, approval of the final version. CR, MD Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. LK, MD Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. SS, MD Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. MV Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. IL, MD Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. GM, MD Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. TN, MD Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, approval of the final version. RB, MD Analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approval of the final version. GDK, MD Conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, approval of the final version.

Competing interests

Irene Lang has relationships with drug and device companies including AOPOrphan Pharmaceuticals, Actelion, Bayer-Schering, Astra-Zeneca, Abbott, Servier, Cordis, Medtronic, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and United Therapeutics. In addition to being investigator in trials involving these companies, relationships include consultancy service, research grants, and membership of scientific advisory boards. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK#1722/2013) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Dalos, D., Gangl, C., Roth, C. et al. Mechanical properties of the everolimus-eluting bioresorbable vascular scaffold compared to the metallic everolimus-eluting stent. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 16, 104 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0296-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0296-1