Abstract

Background

Elevated uric acid (UA) is associated with the presence of the metabolic syndrome (MetS). In a prospective cohort study, we assessed whether baseline and longitudinal change in UA were risk factors for development of MetS and its individual components.

Methods

We included 3087 women and 2996 men who had UA measured in the population based Tromsø Study 1994–95. The participants were stratified according to body mass index (BMI). Endpoints were MetS and each component of the syndrome after 7 years, according to the revised National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) definition.

Results

Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that higher baseline UA was associated with higher odds of developing elevated blood pressure in overweight subjects (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, odds ratio [OR] per 59 μmol/L UA increase 1.44, 95 % confidence interval [CI] = 1.17–1.77, P = 0.001), but not in normal-weight subjects (BMI < 25 kg/m2, P for interaction = 0.04). Overweight also modified the association between baseline UA and the development of elevated fasting glucose (P for interaction = 0.01). UA was a predictor of MetS in all subjects (OR per 59 μmol/L UA increase 1.29, 95 % CI 1.18–1.41, P < 0.001). Furthermore, longitudinal UA change was independently associated with the development of MetS in all subjects (OR per 59 μmol/L UA increase over 7 years 1.28, 95 % CI 1.16–1.42, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Increased levels of baseline UA independently predicted development of elevated blood pressure and higher fasting glycemia in the overweight, but not the normal-weight subjects. Baseline UA and longitudinal increase in UA over 7 years was associated with the development of MetS in all subjects. Whether increased UA should be treated differently in normal-weight and overweight persons needs further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

High levels of serum uric acid (UA) are prevalent in the general population. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2008 UA levels higher than 339 μmol/L were found in 21.6 % of the women, and among men 21.2 % had UA levels higher than 416 μmol/L [1]. Similar prevalence has been found in China [2]. The incidence and prevalence of hyperuricemia is increasing, as reflected by the increase in the incidence and prevalence of gout since the 1960s [3]. In the US, the prevalence of gout more than doubled between 1969 and 1985 [4], may have increased further over the past two decades [1], and has paralleled a significant increase in prevalence of hyperuricemia [1].

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a constellation of interrelated risk factors that increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [5]. MetS is associated with more than two-fold risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular death [6]. The prevalence of MetS is high in most populations, and in the NHANES 2003–2006 about 34 % of US adults ≥20 years of age fulfilled the MetS definition [7]. One study estimated the worldwide prevalence of MetS to range from <10 % to as much as 84 %, depending on region, sex, age and ethnicity [8]. The prevalence of MetS increased significantly between NHANES 1988–1994 and NHANES 1999–2006, and one of the main reasons for this was the increase in abdominal obesity [9]. Overweight and obesity is an increasing global burden [10] and the number of overweight and obese is projected to continue to grow into the future [11].

UA has been reported to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular death in many studies [12–14], but not all [15]. Studies have suggested that hyperuricemia is associated with all of the components of MetS individually: elevated blood pressure [16], obesity [17], high triglycerides [18], low HDL [18] and elevated fasting glucose [19]. Several cross-sectional studies have shown an association between UA and MetS [20, 21], although, after multivariable adjustment, the association disappeared in one study [22]. The role of UA as an independent predictor of the development of MetS has also been examined in several prospective studies. In one study no such association was found [23]. A recent meta-analysis comprising 11 prospective studies concluded that there was an independent, linear dose–response relationship between increasing UA and the development of MetS [24]. As the prevalence of hyperuricemia increases along with the prevalence of overweight and MetS, the causal association between the phenomena remains unsolved. The purposes of the present prospective cohort study were to examine the role of UA and change in UA as a predictor of the MetS and its components after 7 years, and to assess to what extent overweight modified the associations between UA and the metabolic components.

Methods

Study population

The Tromsø Study is a series of population-based, prospective surveys of inhabitants of the municipality of Tromsø, Norway [25]. In 1994–1995, 26,969 subjects were investigated (77 % of eligible subjects). Out of these, all participants aged 55–74 years, as well as smaller (5–8 %) random samples of the other age groups <85 years were invited to the more extensive second-visit examination, and 7445 subjects attended (75 % of eligible subjects). Subjects who attended the second visit in 1994–1995 were eligible for the next survey of 2001–2002. In this survey, 6852 subjects who had partaken in the second visit in 1994–1995, participated (89 % of eligible subjects). The number of subjects who died between the two studies was 495. In the present study, we excluded those with missing serum UA analyses (n = 405), prevalent diabetes at baseline (n = 282; defined as Hba1c ≥6.5 %, non-fasting glucose ≥10.0 mmol/L, under anti-diabetic treatment or self-reported diabetes), and the under-weight subjects (n = 82, body mass index [BMI] < 18.5 kg/m2). Thus, the final study cohort consisted of 6083 subjects at baseline. The University of Tromsø conducted The Tromsø Study in cooperation with The National Health Screening Service. The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics approved the study, and all participants gave their written consent.

Measurements

All participants provided information on diabetes, alcohol and smoking habits, current use of medication and physical activity through a self-administered questionnaire. Experienced nurses made anthropometric measurements. We calculated BMI as weight (kg)/height (m)2. BMI was dichotomized into normal-weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). Blood pressure was recorded in triplet after 5-min seating; the mean of the second and third measurement was used. Physical activity was classified as active (≥1 h physical activity with prominent perspiration or breathlessness per week) or inactive (all others). Smoking habits were classified as non-smokers or current smokers. Alcohol intake was classified as teetotalers, 1–7 units/week and >7 units a week. Non-fasting blood samples were drawn and time since last meal was recorded. Serum UA was measured by photometry with COBAS® instruments (Roche diagnostics, Switzerland) using an enzymatic colorimetric test, the uricase/PAP method. Change in UA (ΔUA) was calculated as serum UA in 2001–2002 minus serum UA in 1994–1995. Creatinine was originally analyzed by a modified Jaffe reaction, but because of a possible drift in the results between baseline and follow-up, 111 plasma samples from the 1994–1995 survey and 142 samples from the 2001–2002 survey were thawed and reanalyzed with an enzymatic method (Modular P/Roche Diagnostics) in 2006, as previously described [26]. Values were fitted to a linear regression model, and recalibrated creatinine values were calculated for all participants. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated according to the CKD-EPI formula [27]. Detailed descriptions of measurements of lipids and HbA1c have been published previously [28].

The metabolic syndrome

Our definition of MetS was based on the revised National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria as published by the American Heart Association [5]. Because our data lacked fasting blood samples, we adjusted the definition of elevated triglycerides and elevated glucose. For the definition of elevated fasting glucose, we set the cut off at ≥7.8 mmol/L if time since last meal was under 4 h and at ≥5.6 mmol/L if time since last meal was at least 4 h. For the definition of elevated triglycerides, we set the cut-off at ≥2.28 mmol/L if time since last meal was under 4 h, as non-fasting triglyceride levels are on average 20 to 30 % higher than fasting levels [29], and ≥1.7 mmol/L if time since last meal was at least 4 h. Thus, the definition of MetS in this study is any three (or more) out of the following five criteria: increased waist circumference (≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men), elevated triglycerides (triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L if time since last meal ≥4 h, ≥ 2.28 mmol/L if time since last meal <4 h or use of lipid-lowering drugs), reduced HDL-cholesterol (HDL < 1.30 mmol/L in women and <1.03 mmol/L in men), elevated blood pressure (≥130 mm Hg systolic blood pressure, ≥ 85 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure or antihypertensive drug treatment) and elevated fasting glucose (glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L if time since last meal ≥4 h, ≥7.8 mmol/L if time since last meal <4 h or on treatment for elevated glucose).

Statistics

Data are given as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Independent sample t-tests and chi square tests were applied to compare baseline variables between participants with normal-weight and overweight. In each of these groups, we assessed Pearson’s correlation coefficient between UA and the baseline variables. We conducted multiple binary logistic regression analyses with each single criterion of MetS and MetS (any three criteria or more) in 2001–2002 as dependent variables and uric acid as an independent variable in separate models. Covariates were sex, age, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, current smoking, physical activity, Hba1c, eGFR, alcohol consumption, use of diuretics and waist circumference at baseline. In each of these analyses, we only included the subjects who did not fulfill the MetS criterion of interest at baseline. We ran the analyses both with the entire cohort and stratified into normal-weight and overweight (BMI < 25 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) at baseline, and interaction between UA and the BMI group was tested for. We also checked for interactions between UA and gender and UA and a BMI-cutoff of obesity (BMI < 30 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) for MetS and each of the MetS criteria. The logistic regression analyses were repeated for the group of subjects who did not have MetS at baseline. Finally, we assessed whether ΔUA was associated with MetS and its components by adding ΔUA as an independent variable to each model. These analyses were also run in the group without MetS at baseline. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We did all the analyses using SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the cohort divided into normal-weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) are shown in Table 1. The differences between the two groups were statistically significant for all the variables. Being overweight, compared to normal-weight, was associated with male gender, older age, and generally a more adverse cardiovascular risk profile, including higher blood pressure, lower eGFR and a poorer lipid profile. On the other hand, there was a larger proportion of smokers in the normal-weight stratum. Also shown in Table 1 is the correlation between each variable and UA. In addition to gender, waist circumference, triglycerides, HDL and MetS correlated strongest with UA, whereas eGFR, use of diuretics, alcohol consumption and blood pressure correlated weaker with UA. The rest of the variables displayed a very weak correlation with UA or no correlation at all. Median time since last meal at baseline was between 2 and 3 h, 16.6 % had at least 4 h since last meal, and 6.1 % had at least 8 h since last meal. In this cohort, 57.9 % of the subjects were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) and 13.5 % were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Associations between baseline UA and subsequent changes in the components of MetS stratified by BMI

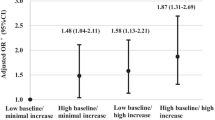

Figure 1 displays the multivariable adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 59 μmol/L (1 mg/dL) UA increase at baseline for acquiring each component of MetS and MetS (three or more components of MetS) after 7 years, stratified by baseline BMI. Each outcome was assessed in the subjects who did not fulfill the criteria for the outcome of interest at baseline. Among the normal-weight individuals, 669 subjects were normotensive at baseline according to the MetS criteria. After 7 years, 251 of them had developed elevated blood pressure. Baseline UA was not a predictor of elevated blood pressure in this group. Among the 450 overweight subjects who were normotensive at baseline, 227 had developed elevated blood pressure 7 years later. Baseline UA was an independent predictor of elevated blood pressure in the overweight (OR per 59 μmol/L UA 1.44, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.17–1.77, P = 0.001). The interaction between the BMI-cutoff and UA for the prediction of new cases of elevated blood pressure was significant (P = 0.04). There were no statistically significant interactions between neither UA and gender nor UA and a BMI-cutoff of obesity (BMI < 30 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) for any of the outcomes.

Multivariable logistic regression with baseline serum uric acid (UA) as predictor of the metabolic syndrome and its components after 7 years, stratified into normal-weight and overweight at baseline by body mass index (BMI). The odds ratio is per 59 μmol/L increase of UA. Bars represent odds ratio; grey bars the normal-weight subjects (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and black bars the overweight subjects (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2). Whiskers represent 95 % confidence interval. The group includes the subjects without each component of MetS of interest or MetS (three or more components) at baseline. Covariates: baseline sex, age, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, current smoking, physical activity, HbA1c, eGFR, alcohol consumption, use of diuretics, and waist circumference. * = P for interaction with BMI-cut-off <0.05. Elevated blood pressure: blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg or treated for hypertension, elevated triglycerides: triglycerides ≥2.28 mmol/L if time since last meal <4 h and ≥1.7 mmol/L if time since last meal ≥4 h or use of lipid lowering drugs, low HDL = HDL < 1.03 mmol/L in men or <1.30 mmol/L in women, elevated fasting glucose = glucose ≥7.8 mmol/L if time since last meal <4 h and ≥5.6 mmol/L if time since last meal ≥4 h or treated for elevated glucose, central obesity = waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women, MetS = three or more MetS components. Abbreviations: HDL high-density lipoprotein, BMI body mass index, MetS metabolic syndrome, UA uric acid, HBA1c hemoglobin A1c, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

BMI also modified the association between UA at baseline and new cases of elevated fasting glucose after 7 years (Fig. 1). In the overweight, baseline UA predicted this outcome (OR per 59 μmol/L UA increase 1.20, 95 % CI = 1.10–1.32, P < 0.001), whereas baseline UA was not significantly associated with new onset fasting glucose elevation for subjects with normal-weight (P for interaction = 0.01). There was no interaction between UA and the BMI cut-off for elevated triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol according to MetS criteria (P for interaction = 0.39 for both), and UA did not significantly predict the development of central obesity according to the MetS criteria in either group.

The association between UA and new cases of MetS

Results of unstratified multivariable logistic regression analyses of the subjects without MetS at baseline are displayed in Table 2. In this group, 611 subjects had MetS 7 years later, and baseline UA was a predictor of this outcome (OR per 59 μmol/L increase 1.29, 95 % CI = 1.18–1.41, P < 0.001).

Change in UA as a risk factor for MetS and its components

Change in UA over 7 years as a predictor of MetS and its single components in 2001–2002 was assessed in multiple logistic regression models. The results are shown in Table 3. An increase in UA by 59 μmol/L over 7 years from baseline implied an increase in odds of MetS of 28 %. UA increase was also an independent risk factor for new cases of elevated blood pressure, elevated triglycerides, low HDL and central obesity. However, longitudinal UA increase was not a risk factor for incident elevated fasting glucose.

Discussion

In this large prospective study of subjects without diabetes from the general population, elevated UA at baseline was independently associated with increased risk of elevated blood pressure in the overweight individuals 7 years later. We found no association between UA and future elevated blood pressure in the normal-weight subjects. Moreover, UA at baseline predicted new-onset impaired fasting glucose in the overweight persons, but not in the normal-weight group. Baseline UA was a predictor of MetS in all subjects. Finally, a longitudinal increase in UA of 59 μmol/L over 7 years raised the odds of developing MetS by 28 %.

The association between UA and MetS is in accordance with previous prospective studies [17, 30, 31]. Few studies have examined the association between longitudinal UA change and MetS. In a healthy Japanese cohort, no significant association was found between 1 mg/dL (59 μmol/L) UA increase and incident MetS [32]. However, in the Japanese study, follow-up time was shorter than in our study, and the authors did not adjust for baseline UA. These methodological differences may in part explain the discrepancies between the results of our study and the study from Japan.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no other studies of this scale where the population is stratified into normal-weight/overweight before examining the association between UA and MetS and its components. A small study (n = 69) from the United Arab Emirates examined the univariable relationship between a set of biomarkers, among them UA, and components of MetS in healthy, young females, stratified into normal-weight (BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI > 25, < 30 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [33]. This study found statistically significant correlations between UA and the waist circumference and triglycerides components only, and the associations were confined to the obese group. The authors found no significant correlation between UA and blood pressure in the strata; this may be due to small sample size and a population of uniform age and sex. In our study, we did not find any statistically significant interaction between the BMI-cutoff of obesity (BMI < 30 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) for neither MetS nor any of its components. This may be due to a small group of obese in our cohort.

The association between hypertension and UA was first noted in the 1870s and has been demonstrated in numerous publications. In a recent meta-analysis, UA increase was reported to be associated with a statistically significant elevation in incident hypertension [16]. It has been claimed that an elevated serum UA is the independent risk factor for hypertension that is the most reproducible to date [34]. A multitude of studies, in an effort to explain how hyperuricemia can lead to hypertension and cardiovascular disease, have proposed interlinked mechanisms such as endothelial dysfunction and reduction in endothelial nitric oxide (NO) levels [35], oxidative stress [36], activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system (RAAS) [37] and renal microvascular lesions [38]. However, we found that UA was a predictor of elevated blood pressure in the overweight, but not in the normal-weight. Few studies have explored this phenomenon. The precursor of UA is xanthine, and the reaction from the latter to the former is catalyzed by the enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), which can exist in two forms, xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) or xanthine oxidase (XO) [39]. The enzyme is mostly in its XDH form, but can be transformed into XO by proteolytic cleavage or oxidation. In the XO form, reactive oxygen species are a by-product of the reaction of xanthine to UA [40]. Therefore, under certain circumstances, increased activity of XO, detected as elevated production of UA, will lead to increased oxidative stress, which, in turn, can be detrimental in the state of reduced antioxidant capacity that accumulated fat creates [41]. Furthermore, UA can affect adipocytes by inducing upregulation of pro-inflammatory factors and downregulation of the insulin sensitizer and anti-inflammatory factor adiponectin [42]. Adiponectin is negatively associated with BMI and body-fat [43]. Since low levels of adiponectin is associated with the development of hypertension [44] and insulin resistance [45], it could be speculated that adiponectin is part of the link between UA and elevated blood pressure and insulin resistance, and explain why UA is associated with new onset elevated blood pressure and impaired fasting glucose in the overweight but not the normal-weight in our study. Furthermore, a study found increased angiotensinogen levels in the hypertensive overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), compared to the hypertensive normal-weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), in the presence of hyperuricemia [46], and a rodent model demonstrated that UA-mediated upregulation of adipose RAAS caused insulin resistance [47]. UA might also directly contribute to the development of insulin resistance in adipose tissue, possibly through redox modulation [48]. These could also be mechanisms in which UA is associated with overweight-related elevated blood pressure and elevated fasting glucose.

Epidemiologically, UA is associated with insulin resistance [49], and the development of insulin resistance is often preceded by hyperuricemia [50]. MetS does not comprise a uniform group of subjects; Sperling et al. of The Cardiometabolic Think Tank present a subtype where insulin resistance is dominant [51]. An association between hyperuricemia and insulin resistance could in part explain the development of MetS.

The present study has important strengths: the large size, solid attendance rate, long follow-up time, use of UA as a continuous variable, and the ability to correct for confounders such as eGFR, use of diuretics and all the traditional cardiovascular risk factors. However, a major shortcoming of our study is the lack of fasting blood samples. In particular, glucose and triglycerides, and thereby the definition of MetS, are affected by this. The incorporation of time since last meal and adjustment of the cut-offs in the definition of elevated fasting glucose and elevated triglycerides compensated in part, but not fully, for this limitation. In addition, only a single measurement of serum UA was done in each survey. Another shortcoming of this study may be the fact that our baseline data were collected 21–22 years ago, and 14–15 years have passed since follow-up. Both lifestyles and pharmacological treatment have changed in that time. However, if the effects of overweight on UA’s association with MetS can be reproduced in studies on newer data, our findings may be even more relevant as overweight and obesity is an even greater challenge in the world of today. That our study population comprised largely of healthy, middle-aged to elderly Caucasians can be viewed as both a weakness and a strength; the results may not be generalizable to dissimilar populations, but the homogeneity of our cohort may have prevented dilution of our findings due to important diversities in baseline properties.

Conclusion

In a large cohort from the general population, baseline UA was independently associated with future cases of elevated blood pressure and elevated fasting glucose in overweight subjects, but not normal-weight individuals. Both elevated baseline UA and longitudinal increase in UA over 7 years from baseline was associated with the development of MetS in all subjects. These findings warrant further studies to examine the exact causal relationship between UA and MetS, in overweight as well as in normal-weight individuals, and to assess whether treatment strategies need to be targeted differentially according to BMI.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics approved the study (committee’s reference number 2009/2536-3), and all participants gave their written consent to participate. The Tromsø Study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is legally restricted. It will therefore not be shared publicly. However, meta-data as well as general information about the study is available at http://tromsoundersokelsen.uit.no/tromso.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CKD-EPI:

-

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HBa1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- HDL:

-

high-density lipoprotein

- MetS:

-

the metabolic syndrome

- NCEP-ATP III:

-

National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RAAS:

-

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- UA:

-

uric acid

- ΔUA:

-

change in quantity of uric acid

References

Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3136–41.

Nan H, Qiao Q, Dong Y, Gao W, Tang B, Qian R, et al. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in a population of the coastal city of Qingdao, China. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1346–50.

Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, Doherty M. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. Nature Publishing Group; 2015;11:649-662. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91.

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52.

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32.

Ervin RB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adults 20 years of age and over, by sex, age, race and ethnicity, and body mass index: United States, 2003–2006. Natl. Health Stat. Report. 2009;13:1-7. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr013.pdf.

Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/943162.

Mozundar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1–4.

Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–67.

Kelly T, Yang W, Chen C-S, Reynolds K, He J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1431–7.

Fang J, Alderman M. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality: the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971–1992. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2404–10.

Holme I, Aastveit AH, Hammar N, Jungner I, Walldius G. Uric acid and risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and congestive heart failure in 417 734 men and women in the Apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk study (AMORIS). J Intern Med. 2009;266:558–70.

Storhaug HM, Norvik JV, Toft I, Eriksen BO, Løchen M-L, Zykova S, et al. Uric acid is a risk factor for ischemic stroke and all-cause mortality in the general population: a gender specific analysis from The Tromsø Study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:115.

Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:7–13.

Grayson PC, Young Kim S, Lavalley M, Choi HK. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:102–10.

Zhang Q, Zhang C, Song X, Lin H, Zhang D, Meng W, et al. A longitudinal cohort based association study between uric acid level and metabolic syndrome in Chinese Han urban male population. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:419.

Lin S-D, Tsai D-H, Hsu S-R. Association between serum uric acid level and components of the metabolic syndrome. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:512–6.

Dehghan A, Van Hoek M, Sijbrands EJG, Hofman A, Wetteman JCM. High serum uric acid as a novel risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Metab Risk. 2008;31:2007–8.

Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. Am J Med. 2007;120:442–7.

Lee J-M, Kim HC, Cho HM, Oh SM, Choi DP, Suh I. Association between serum uric acid level and metabolic syndrome. J Prev Med Public Health. 2012;45:181.

Ziaee A, Esmailzadehha N, Ghorbani A, Asefzadeh S. Association between uric acid and metabolic syndrome in Qazvin Metabolic Diseases Study (QMDS), Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:155–65.

Ferrara LA, Wang H, Umans JG, Franceschini N, Jolly S, Lee ET, et al. Serum uric acid does not predict incident metabolic syndrome in a population with high prevalence of obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:1360–4.

Yuan H, Yu C, Li X, Sun L, Zhu X, Zhao C, et al. Serum uric acid levels and risk of metabolic syndrome: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:4198–207.

Jacobsen BK, Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Njølstad I. Cohort profile: the Tromsø study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:961–7.

Kronborg J, Solbu M, Njølstad I, Toft I, Eriksen BO, Jenssen T. Predictors of change in estimated GFR: a population-based 7-year follow-up from the Tromsø study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2818–26.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12.

Joseph J, Svartberg J, Njølstad I, Schirmer H. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes in groups stratified according to metabolic syndrome: a 10-year follow-up of the Tromsø Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:117–24.

Cholesterol N, Program E. Metabolic Syndrome vs Framingham Risk Score for Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2644–50.

Babio N, Martínez-González MA, Estruch R, Wärnberg J, Recondo J, Ortega-Calvo M, et al. Associations between serum uric acid concentrations and metabolic syndrome and its components in the PREDIMED study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:173–80.

Lee J, Ryoo J, Choi J, Park SK. Serum uric acid level and the incidence of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged Korean men: a 5-year follow- up study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2014;47(6):317-26.

Oda E. Serum uric acid is an independent predictor of metabolic syndrome in a Japanese health screening population. Heart Vessels. 2014;29:496–503.

Abdullah AR, Hasan HA, Raigangar VL. Analysis of the relationship of leptin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, adiponectin, insulin, and uric acid to metabolic syndrome in lean, overweight, and obese young females. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:17–22.

Kanbay M, Segal M, Afsar B, Kang D-H, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Johnson RJ. The role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of human cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2013;99:759–66.

Mercuro G, Vitale C, Cerquetani E, Zoncu S, Deidda M, Fini M, et al. Effect of hyperuricemia upon endothelial function in patients at increased cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:932–5.

Sautin YY, Nakagawa T, Zharikov S, Johnson RJ, Cell JP. Adverse effects of the classic antioxidant uric acid in adipocytes: NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative/nitrosative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;0224:584–96.

Eräranta A, Kurra V, Tahvanainen AM, Vehmas TI, Kööbi P, Lakkisto P, et al. Oxonic acid-induced hyperuricemia elevates plasma aldosterone in experimental renal insufficiency. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1661–8.

Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21.

Kang DH, Ha SK. Uric acid puzzle: dual role as anti-oxidantand pro-oxidant. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2014;12:1–6.

Berry CE, Hare JM. Xanthine oxidoreductase and cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. J Physiol. 2004;555:589–606.

Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–61.

Baldwin W, McRae S, Marek G, Wymer D, Pannu V, Baylis C, et al. Hyperuricemia as a mediator of the proinflammatory endocrine imbalance in the adipose tissue in a murine model of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2011;60:1258–69.

Matsubara M, Maruoka S, Katayose S. Inverse relationship between plasma adiponectin and leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:173–80.

Chow WS, Cheung BMY, Tso AWK, Xu A, Wat NMS, Fong CHY, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia as a predictor for the development of hypertension: a 5-year prospective study. Hypertension. 2007;49:1455–61.

Yamamoto Y, Hirose H, Saito I, Nishikai K, Saruta T. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived protein, predicts future insulin resistance: two-year follow-up study in Japanese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:87–90.

Zhang J, Zhang Y, Deng W, Chen B. Elevated serum uric acid is associated with angiotensinogen in obese patients with untreated hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2014;16:569–74.

Zhang J-X, Zhang Y-P, Wu Q-N, Chen B. Uric acid induces oxidative stress via an activation of the renin-angiotensin system in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Endocrine. 2014;48:135–42.

Zhu Y, Hu Y, Huang T, Zhang Y, Li Z, Luo C, et al. High uric acid directly inhibits insulin signalling and induces insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;447:707–14.

Yoo TW, Sung KC, Shin HS, Kim BJ, Kim BS, Kang JH, et al. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration and insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Circ J. 2005;69:928–33.

Carnethon MR, Fortmann SP, Palaniappan L, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Chambless LE. Risk factors for progression to incident hyperinsulinemia: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study, 1987–1998. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1058–67.

Sperling LS, Mechanick JI, Neeland IJ, Herrick CJ, Després J-P, Ndumele CE, et al. The CardioMetabolic health alliance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1050–67.

Acknowledgements

We thank the late Professor Ingrid Toft who conceived this study, without you, none of this would have been possible.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from Northern Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Nord).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Study design: JVN, HMS and MDS. Data analyses: JVN, HMS and MDS. Writing the first draft: JVN, HMS and MDS. Data interpretation, discussion and preparation of the final manuscript: JVN, HMS, KY, TGJ, SNZ, BOE and MDS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Norvik, J.V., Storhaug, H.M., Ytrehus, K. et al. Overweight modifies the longitudinal association between uric acid and some components of the metabolic syndrome: The Tromsø Study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 16, 85 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0265-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-016-0265-8