Abstract

Background

The increasing temperature associated with climate change impacts grapevine phenology and development with critical effects on grape yield and composition. Plant breeding has the potential to deliver new cultivars with stable yield and quality under warmer climate conditions, but this requires the identification of stable genetic determinants. This study tested the potentialities of the microvine to boost genetics in grapevine. A mapping population of 129 microvines derived from Picovine x Ugni Blanc flb, was genotyped with the Illumina® 18 K SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) chip. Forty-three vegetative and reproductive traits were phenotyped outdoors over four cropping cycles, and a subset of 22 traits over two cropping cycles in growth rooms with two contrasted temperatures, in order to map stable QTLs (Quantitative Trait Loci).

Results

Ten stable QTLs for berry development and quality or leaf area were identified on the parental maps. A new major QTL explaining up to 44 % of total variance of berry weight was identified on chromosome 7 in Ugni Blanc flb, and co-localized with QTLs for seed number (up to 76 % total variance), major berry acids at green lag phase (up to 35 %), and other yield components (up to 25 %). In addition, a minor QTL for leaf area was found on chromosome 4 of the same parent. In contrast, only minor QTLs for berry acidity and leaf area could be found as moderately stable in Picovine. None of the transporters recently identified as mutated in low acidity apples or Cucurbits were included in the several hundreds of candidate genes underlying the above berry QTLs, which could be reduced to a few dozen candidate genes when a priori pertinent biological functions and organ specific expression were considered.

Conclusions

This study combining the use of microvine and a high throughput genotyping technology was innovative for grapevine genetics. It allowed the identification of 10 stable QTLs, including the first berry acidity QTLs reported so far in a Vitis vinifera intra-specific cross. Robustness of a set of QTLs was assessed with respect to temperature variation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Climate change is expected to modify several environmental factors, including temperature, CO2 concentration, radiation level, water availability, wind speed and air moisture, and to noticeably affect crop production [1]. Air and land temperatures on Earth’s surface are predicted to increase from 1.1 to 6.4 °C by the end of the 21th century [2], in addition to the past temperature rises. Temperature and rainfall are major climatic factors influencing grapevine phenology, yield, berry composition and wine quality [3, 4]. Heat stress is more difficult to cope with than drought stress, which can be mitigated through irrigation or rootstock selection [5]. According to Hannah et al. [6], most of vine growing regions will undergo a global warming of 2 °C to 4 °C in the next decades. Mild to moderate temperature increases (less than +4 °C compared to ambient temperature) were shown to advance grapevine vegetative development and the whole fruit ripening period up to five weeks earlier, i.e. at the time of maximum summer temperatures [4, 7, 8]. Phenological changes may negatively impact berry development program and composition. Indeed, warmer climate in the past resulted in higher sugar level and lower contents of organic acids, phenolics and aroma [9–13]. Such alterations of berry composition directly impair the organoleptic quality and the stability of wines [14]. Moreover, high temperature promotes disease development [15], reduces carbohydrate reserves in perennial organs [16], decreases bud fertility, inhibits berry set and, as a result, lowers final yield [17–19].

Negative impacts of climate change on viticulture sustainability and wine quality may be mitigated by: i) viticultural practices such as irrigation or canopy management [20], ii) wine processing like acidification or electro-dialysis, iii) shifting of the vine growing areas towards higher altitude or latitude regions [6, 21, 22] and iv) breeding new cultivars better adapted to the climate changes [23]. The first two methods are widely used, although they are only short-term solutions with limited efficiency. The shift of grape growing areas to cooler climate regions would have dramatic socio-economic consequences. Thus, the development of new cultivars appears to be the best long-term solution for a sustainable viticulture maintaining premium wine production under global warming. However, it requires improving the knowledge on the genetics of key grapevine functions under various environments.

Quantitative Trait Loci (QTLs) repeated over years have been identified in grapevine in usual climate and cultivation conditions. They are notably QTLs for berry size and seedlessness [24, 25], yield components [26], phenology [27, 28], muscat flavour [29, 30], anthocyanin composition [31], tannin composition [32], fruitfulness [33], cluster architecture [34] and disease resistance (e.g. [35, 36]). However, no attempts have been made to test their stability regarding large temperature variations. Molecular physiology and genetic studies have increased our knowledge on the regulation of grapevine reproductive development, including flowering [37], berry growth [38, 39], organic acid pathways [40], tannin [41] or anthocyanin accumulation [42, 43] and sugar uploading [44]. The physiological and molecular adaptation of the grapevine to heat stress was recently addressed. Although a slight temperature increase accelerates berry development, high temperatures and/or heat stress (>35 °C) were shown to produce opposite effect, thus delaying berry ripening [4, 17]. Luchaire et al. [45] and Rienth et al. [46] showed that the carbon flow toward the internodes was dramatically impaired under heat stress, leading to increasing the flowering to ripening time-lag, and to noticeable reprogramming of berry transcriptome.

The genetic control of grapevine adaptation to abiotic stresses remains poorly understood because it requires experimentations on large populations under multi-environment conditions. A few QTLs for water use efficiency and transpiration under duly controlled water stress have been found [47, 48]. Regarding the adaptation to temperature stress, no QTL has yet been identified in grapevine. However, the identification of genetic determinants is critical for the development of temperature-tolerant grapevine cultivars. Furthermore, as for other perennial crops, grapevine breeding is a slow and challenging process in order to combine desirable fruit quality and disease tolerance traits [49]. In grapevine, the breeding process can be noticeably accelerated combining marker-assisted selection [50] and short cycling material such as the microvine [51].

The aim of this work was to identify stable QTLs for a large set of vegetative and reproductive traits in grapevine under contrasted temperature conditions. A pseudo-F1 mapping population of 129 microvine offsprings, derived from a cross between the Picovine [51] and the Ugni Blanc flb mutant [52] was genotyped using a 18 K Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Illumina® chip and phenotyped for 43 traits over up to nine cropping cycles. Fourteen QTLs for berry development and composition or leaf area were found repeated over at least two conditions, among which 10 were stable over at least half of the environments explored.

Results

Phenotypic data

The grapevine population from Picovine 00C001V0008 x Ugni Blanc flb (V. vinifera L.) was phenotyped in nine experimental conditions for up to 43 vegetative and reproductive traits (Table 1).

The distributions of phenotypic data in all environments are shown in Additional file 1. Broad sense heritability and the median, maximum and minimum values for each trait are given in Table 2. All traits displayed continuous variation within environments. Seed number per berry was clearly bimodal. Some growth conditions induced very different distributions (Additional file 1), indicating that individuals displayed different plasticity of studied traits to environmental changes (mainly temperature) within the population. This was particularly true tartrate ratio/tartrate ratio. For most phenotypes, the population showed a large segregation of the phenotypes, e.g.: phyllochron (PHY; 15 to 120 GDD/leaf), leaf area (LA; 10 to 290 cm2/leaf), number of pre-formed inflorescences in winter buds per plant (NBI; 0.25 to 3.8), number of berries per cluster (NB; 5 to 75), berry weight at green lag phase (BWG; 0.2 to 2.2 g), berry weight at maturity (BWM; 0.5 to 3.2 g), total berry acidity at green lag phase (ToAG; 220 to 780 mEq/kg.FW), malate/tartrate ratio at green lag phase (MTG; 0.75 to 5.2), total sugars at green lag phase (ToSG; 5 to 120 mM/kg.FW), total sugars at maturity (ToSM; 350 to 1200 mM/kg.FW), potassium content at green lag phase (KG; 15 to 120 mM/kg.FW).

For each environment, all 43 traits were classified according to the Ward hierarchical classification in order to assess correlations between them (Additional file 2). Berry weight at green and maturity stages (BWG, BWM) remained highly correlated regardless of the environment and this also was found true for the correlation between leaf area (LA) and internode length (IL) (Fig. 1a). Moreover, tartrate concentration and tartrate/total acid ratio at green lag phase (TaG, TOG) were correlated to each other and also linked with the number of berries and clusters (NB, NC). However TaG was not related to malate concentration (MaG), which correlated with sugar concentration traits at green lag phase (Fig. 1b).

Seventeen of the 43 phenotyped traits showed correlations (r ≥ 0.6) between at least two environments (Additional file 3), but only the number of seeds showed such correlations between all environments.

Most of the models selected to estimate heritability included the environment effect (data not shown). Broad sense heritability (H 2) of the inter-environment genotypic means varied from 0.01 to 0.80 (Table 2), and it was higher than 0.40 for 12 traits out of 43. The number of seeds per berry and berry weight at green lag phase and maturity displayed the highest heritabilities (0.80, 0.67 and 0.52, respectively).

Genetic maps

Out of the 18 K SNPs on the chip, 6,000 were polymorphic in this population and yielded good quality genotyping data. A subset of these SNPs was selected to build a framework map for each parent suitable for initial QTL detection, with a marker density appropriate for this population size.

The paternal genetic map (Ugni Blanc flb; Additional file 4 part A) consisted of 714 SNP markers (of segregation type aaxab only) mapped on 19 linkage groups and covering a total of 1,301 cM. Coverage was mostly satisfying with an average distance of 1.8 cM between adjacent markers and 302 kb/cM. However, some LG parts were not covered, mainly due to the discarding of monomorphic markers (55 % of all initial markers; Additional file 5). It was not due to the absence of markers on the 18 K chip in these regions, since there was no distance between adjacent markers larger than 0.5 Mb on this chip (A. Launay, personnal communication). In a few map gaps however, only non-vinifera markers had been defined on the chip, which may not have amplified on this V. vinifera population. In two specific regions of LGs 2 and 18, harboring the sex and Flb loci, respectively [38, 53], there was simply no male segregation in the population, since the Picovine was homozygous and Ugni Blanc flb heterozygous at both these loci and only hermaphrodite offspring with no fleshless berries were retained for this study. All markers from paternal LG 2, on each side of the selected region, exhibited high segregation distortion.

The maternal genetic map (Picovine 00C001V0008; Additional file 4 part B) consisted of 408 SNP markers (353 of type abxaa and 55 of type abxab) mapped on 18 linkage groups spanning a total of 606 cM, with an average inter-marker distance of 1.5 cM and 390 kb/cM. Compared to the paternal map, the number of markers and genome coverage in the maternal map were halved, resulting in a smaller map with markers not covering the entire genome. Picovine comes from a self-fertilization of a microvine [51]. Thus, it is highly homozygous (54 %; MR Thomas, personal communication). LG 7 was even totally missing in the maternal map. Nevertheless, a good colinearity was found between the order of genetic markers and their physical localisation on the genome, in both maps (Additional file 6).

QTL detection

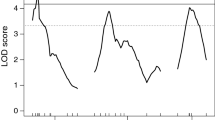

A hundred and fourteen significant QTLs were identified on parental maps (Additional file 7). Among them, 14 were detected under two environments or more. In this study, a focus was placed on these repeated QTLs only (Table 3; Fig. 2). These QTLs concerned 11 out of the 43 phenotyped traits and were related to leaf area and berry trait variations. Ten of these QTLs were considered as stable since they were detected in at least half of the conditions explored. No repeated QTLxQTL interaction was found.

Localisation on the parental genetic maps of a microvine population, of QTLs repeated in at least two different conditions. Stable QTLs, found in at least half of the explored conditions, are displayed in blue. Bars indicate the maximum and minimum value of LOD-1 confidence intervals from QTLs for the same traits identified under at least two environments. Black boxes represent the range of peak LOD values over the different environments. Distances are in Kosambi cM. BWG: Berry weight at green lag phase; BWM: Berry weight at maturity; LA: Leaf area; MOG: Malate/total acids ratio at green lag phase; MTG: Malate/tartrate ratio at green lag phase; NB: Number of berries per cluster at maturity; NC: Number of clusters per ten phytomers at maturity; NS: Number of seeds per berry at maturity; TaG: Tartrate at green lag phase; ToAG: Total acids at green lag phase; TOG: Tartrate/total acids ratio at green lag phase

Leaf area

Two repeated QTLs explaining up to 12 % and 17 % of leaf area variation were found on Picovine LG 19 and on Ugni Blanc flb LG 4, respectively. The LG 4 QTL was stable over half of the conditions. No repeated QTL was detected for other vegetative traits (BB, PHY, LMA and IL) that varied within environments.

Seed number, berry weight, number of berries and clusters

A new major QTL for the number of seeds per berry (NS) was found on Ugni Blanc flb LG 7 in all studied environments, where it explained 48 % to 76 % of the total variance (Table 3 and Fig. 2). This major QTL co-localized with the QTLs for berry weight at green lag phase (BWG) and at maturity (BWM), which explained 25-44 % and 17-42 % of total variance, respectively, in the different conditions investigated. Stable QTLs for the number of clusters (NC) and the number of berries per cluster (NB) were also localized in the same region, explaining 13-25 % and 18-24 % of total variation, respectively. Another repeated QTL for the number of berries per cluster (NB), explaining 13–18 % of total variance, was detected twice on LG 14 in Ugni Blanc flb.

Berry organic acid contents

Major and minor QTLs for malate and tartrate contents at green lag phase were identified in Ugni Blanc flb and Picovine. Five stable QTLs were discovered, for malate/total acid (MOG), malate/tartrate (MTG), and tartrate/total acid (TOG) ratios and for berry tartrate concentration (TaG) in Ugni Blanc flb, explaining from 12 % to 35 % of total variation. Four of them co-localized with the seed number and berry weight QTLs on LG 7. Another TaG QTL was identified on LG 4 in Ugni Blanc flb, but contrary to the LG 7 TaG QTL, it did not co-localize with QTLs for the dimensionless traits MTG, MOG or TOG. Only one minor repeated QTL for a berry acidity trait was detected twice in Picovine, at the top of LG 5, explaining 6 % to 12 % of the total berry acid concentration (ToAG) variance at green lag phase.

Candidate genes

The size of integrated QTL confidence intervals (see Methods) varied from 3.1 to 14.0 Mb (Table 4) and harbored from 302 to 1201 genes per QTL. As a first approach, we screened these candidate genes taking into account their functional annotations (Additional file 8) and expression patterns (Additional file 9), which reduced by four to 28 times the number of most probable candidate genes per QTL (Table 4). The distribution of these selected candidate genes according to each main biological function is shown in Additional file 10.

Discussion

This QTL study, merging extensive phenotyping data (up to 43 traits, including five vegetative ones and 38 reproductive ones, assessed in nine environments) with a high-density genetic map obtained with the 18 K SNP Chip, led to identify 10 new stable QTLs. Some traits regarding berry acidity were mapped in Vitis vinifera for the first time and new genome regions were identified for these and other traits. QTL stability assessment was expanded towards an unprecedented temperature variation range (average T°max - T°min) thanks to the possibility to grow the microvine progeny in tightly controlled conditions, which is almost impossible with standard non-dwarf vines.

Segregation extent and heritability of phenotyped traits in the population

The dwarf mapping population showed berry weight and composition variations consistent with those generally reported for grapevine. Indeed, berry weight of extreme individuals ranged from 0.2 g to 2.2 g at green lag phase, and from 0.5 g to 3.2 g at maturity stage. Similar variations were reported by Houel et al. [54] on a set of 165 V. vinifera wine varieties, including the ones used to generate the progeny: cv. Ugni Blanc and Pinot Meunier. Similar variation extent was also reported by Doligez et al. [25] in a segregating population from a cross between two other cultivars, Syrah and Grenache. In accordance with previous results on V. vinifera [55], the average total acid and potassium concentrations in fruits within the population were 509 and 53 mEq/kg.FW, respectively, at green lag phase. They decreased to respectively 197 and 87 mEq/kg.FW at berry maturity. The variation magnitude for total acid and potassium concentrations in ripe fruit observed between extreme individuals (3 to 5 fold) was the same as in another V. vinifera progeny (unpublished data).

These results indicate that, for reproductive traits, the Picovine 00C001V0008 x Ugni Blanc flb (V. vinifera L.) progeny behaved like other V. vinifera progenies. Interestingly, a correlation between glucose plus fructose and malate concentrations emerged at the green lag phase (Fig. 1b), namely before the onset of ripening, which was not documented before. Increased total sugar concentration is not an artifact due to the casual presence of ripe berries in green lag phase samples, since this would have resulted in a decrease in malate, conversely to what was actually observed. The level of sugars at the end of the first berry growth phase remains quite low and this illustrates that organic acids are by far the major osmoticum as compared to sugars, the opposite being true during the ripening phase (Additional file 1). Moreover, our results also suggest that malate, as a lower cost osmoticum, becomes even more favoured upon the impairment of the carbon balance, in different genotype x environment conditions.

In our study, some traits displayed lower broad-sense heritability than in previous studies, particularly acid or sugar-related traits at maturity. In previous studies, broad-sense heritability was most often above 0.5. At maturity, it was 0.61-0.94 for total sugar content [56, 57], 0.68-0.91 for malic acid and 0.47-0.75 for tartaric acid contents [56], 0.53-0.90 for total acids content [56, 58], 0.49-0.93 for berry weight [54, 58–62], 0.34 for seed number [59], 0.43 for number of berries per cluster [62], 0.55-0.94 for number of clusters [57, 62]. Broad-sense heritability was 0.96 for berry weight at véraison [54] and 0.67-0.82 for leaf area [48]. The temperature range explored in our study was very large thanks to the use of growth rooms (Additional file 11), and environmental variation may be inflated in our study compared to previous ones, especially to those reporting within-year heritabilities. This may partly explain the discrepancy between our estimates and the previous ones. Another possible explanation arises from the various ways maturity stage is assessed among studies (fixed véraison-maturity time-lag, seed color change, etc.; note that in many studies, maturity stage is not even defined). This may have biased genetic variance estimates in some studies. Last but not least, genetic variation and thus heritability strongly depends on the QTLs segregating in each cross, as suggested by the large range of estimates among studies for a given trait. In particular, genetic variation is expected to be larger in interspecific crosses than in pure V. vinifera ones.

New QTLs for berry yield components

In addition to the number of clusters per axis, berry weight and number per cluster are key determinants of grapevine yield. QTLs for the number of seeds per berry (NS) and berry weight (BWM) in one or more years were already reported on linkage groups 2, 4, 8, 18 and 1, 5, 8, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, respectively [24–26, 63–66]. But this is the first time that major QTLs for NS, BWG and BWM are detected on LG 7 in grapevine. The parents of the present cross were related to wine cultivars from Northern and Western France (Pinot and Ugni Blanc), whereas the parents in previous V. vinifera QTL studies for these traits were wine cultivars from Southern France and Spain (Syrah and Grenache) or related to table cultivars (Big Perlon, Muscat, Sultanine, etc.) from Italy, Spain, Eastern Europe, etc. Therefore, since different selection histories have certainly produced various heterozygosity status among these parents, it is not surprising to find novel QTLs in the present study.

Moreover, QTLs for NS, BWG and BWM co-localized on LG 7 and showed decreasing variance, suggesting that a major locus might affect seed and berry cell numbers simultaneously during early development, or alternatively that expansion might indirectly be controlled by seeds through growth regulators control, later on in the development [67]. This result is consistent with the co-localization of seed trait QTLs with the major berry weight QTL on LG 18 in the seedless context [24, 25, 63–65], but contrasts with the lack of co-localization of any other seed trait QTLs with berry weight QTLs in any cross reported to date in grapevine. The consequences for use in breeding will therefore differ for this particular locus. The high correlation between BWG and BWM in this population is consistent with our previous finding on a sample of 254 varieties of Vitis vinifera. Indeed, the main determinants of the genetic variation for berry size were shown to be active before the green lag phase of berry growth [54].

Stable QTLs were also identified on LG 7 for the number of berries per cluster and the number of clusters per phytomer (NB, NC) and a repeated one was found on LG 14 for NB. Only the NB QTL on LG 7 co-localized with a similar one identified by Fanizza et al. [26] in one year only.

Grape berry acidity QTLs

Grape berry acidity is known to be severely impacted by temperature during the growing season and should become a target of prime importance for breeding [68–70]. We showed here that malic acid may be strongly impacted by temperature during the green growth stage, and that the malate/tartrate ratio may strongly vary, depending on environmental conditions, while the total acid concentration is more stable (Additional file 1). Here, several stable QTLs regarding berry organic acid contents at green lag phase were identified for the first time in a pure intra-specific V. vinifera cross. Chen et al. [71] recently reported two-year repeated QTLs for malate and tartrate/malate ratio on LG 18 in a complex interspecific cross between several Vitis species. Two major tartrate concentration (TaG) QTLs were detected on Ugni blanc flb LGs 4 and 7, explaining each from 12 % to 35 % of total variance. They are the first stable significant tartrate QTLs reported in grapevine. A single-year phenotyping study previously led to the identification of putative only QTLs for berry pH and tartaric acid concentration in an interspecific cross [66]. According to our results, it will be possible to modify tartrate concentration in berries by breeding within V. vinifera, without resorting to interspecific crosses. This is a highly valuable result, since interspecific introgression schemes are more complex and introduce some undesired characteristics in wine taste, which are not widely accepted, interspecific hybrids even being often merely forbidden.

Tartrate synthesis occurs quite rapidly following fecundation. Then, its concentration decreases, due to dilution, while malate and sugars become the major osmoticum in green and ripe berries, respectively. Such a mechanism makes TaG dependent not only on tartrate synthesis, but also on berry expansion and malate synthesis. Dimensionless calculated traits such as the malate/tartrate ratio or the tartrate or malate relative contribution ratios (MTG, MOG or TOG) confirmed the LG 7 acidity QTL in all environmental conditions investigated. Puzzlingly, this was not the case for the LG 4 QTL, suggesting that these QTLs could act through the genetic control of intrinsically different events. In this respect, the co-localization of seed number, berry weight, and malate/tartrate QTLs on LG 7 may not be circumstantial. Its most parsimonious interpretation is that a single gene expressed during early berry development would affect seed number, which in turn would drive malate synthesis and cellular expansion, which is linked to increased malate/tartrate ratio [52]. Further experiments addressing cell number and the kinetics of malate and tartrate accumulation on extreme phenotypes are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

QTLs for leaf area and other traits

In this study, two QTLs have been identified for leaf area (LA) on LGs 4 and 19. Two previous studies reported QTLs for leaf morphology and area in grapevine [48, 72] that did not co-localize with our repeated LA QTLs. However, one LA QTL identified only once (Additional file 7) co-localized with one QTL mentioned by Coupel-Ledru et al. [48] on LG 17. These discrepancies between studies highlight the polygenic determinism of berry weight, seed number and leaf area, with different genes or alleles segregating in different populations.

In this study, QTLs for PHY, IL, PIF, PFV, MaG, CiG, COG, CiM, MOM, TOM, COM, MTM, ToSG, KG, ASKG, GFM, ToSM and KM traits were found in one growing condition only (Additional file 7), suggesting frequent occurrence of genotype x environment interactions. For some other traits (BB, LMA, NBI, PBI, SW, MaM, TaM, ToAM, GuG, FuG, GFG, GuM, FuM, ASKM), no significant QTL was detected. For some of these traits, especially those with a low heritability, the parents of the cross might simply not be heterozygous for the main underlying genes. For the other traits, the reason might be the limited power for detecting small QTLs which results from the limited population size. Moreover, the berry weight QTL was detected in fewer environments at fruit maturity than at green lag phase. Furthermore, the QTL of berry tartrate content identified at green lag phase disappeared at maturity. This may reflect increased berry sampling errors due to the increase of berry heterogeneity during ripening or to inaccurate assessment of ripe stage, in the absence of precise kinetic measurements.

Co-localization of QTLs and correlations

Nine berry or organic acid-related QTLs co-segregated on LG 7. Some of these traits were highly correlated, based on the Ward hierarchical classification. The negative correlation between number of berries (NB) and number of clusters (NC) likely results from plant physiological limitation, possibly insufficient carbon supply, to allow for fruit development and ripening. QTLs for NB and NC had small effects but also small heritability. QTLs for berry weight had large effects compared to their H 2. Therefore, their co-localization on LG 7 alone could explain their observed correlation. Final berry weight is determined early during berry development and organic acids constitute the major osmoticum for vacuolar enlargement during the green growth stage, supporting a nine-fold increase of the berry cell volume between anthesis and the onset of ripening [73].

Finally, the lack of phenotypic correlation between traits showing QTLs co-localized on LG 7 might be explained by other QTLs, not detected in this study and not co-localized, but also by a lack of environmental correlation. Although leaf area (LA) and internode length (IL) were positively correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.71 over all environments, Fig. 1a) and heritability was slightly higher for IL than for LA, repeated QTLs were found only for LA and not for IL, suggesting that this newly reported correlation was mainly of environmental rather than of genetic origin.

QTLs stable under different environments

In grapevine, two studies on the genetic determinism of adaptation to water stress allowed the identification of QTLs involved in the acclimation of scion transpiration induced by rootstock [47] and in the regulation of leaf water potential under soil drought partly due to reduced leaf transpiration [48]. Selection of allelic variation at these QTLs appears to be a promising way to select new cultivars to face climate change.

In our study, although the population showed a response of both vegetative and reproductive traits to thermal chart variations (growth rooms experiment), no repeated QTL could be evidenced for trait difference between the two temperature conditions (Additional file 7). Since response to temperature exhibited a large variability for each trait, the absence of QTLs for this response seemed to be rather due to low heritability (data not shown). Nevertheless, 10 QTLs stable under different environments mainly differing in terms of temperature have been found. By design, in all environments, the progeny was grown in 3 L pots with the same substrate and non-limiting irrigation. Moreover, in using growth rooms, our objective was to obtain differences only in temperature, since photoperiod, air vapour pressure and radiation level were regulated. These QTLs thus represent another very interesting genetic potential for the delivery of new cultivars with stable yield and quality under warmer climate conditions.

Candidate genes

The integrated confidence intervals around repeated QTLs (from 3.1 to 14.0 Mb) were large, harbouring several hundred genes. Such interval sizes make the identification of candidate genes particularly tricky, insofar as gene annotation remains perfectible in grapevine. Low acidity phenotypes were recently attributed to mutations in an aluminium activated malate transporter in apple, and in an uncharacterized transporter in Cucurbits (MDP0000252114 [74]; XP_008463303 [75]), but no genes co-localizing with acidity QTLs in Vitis exhibited significant homologies with them (BLASTP, data not shown). Moreover, organ specific traits may be indirectly controlled by genes expressed elsewhere in the plant. Keeping these reserves in mind, as a first approach, we have screened candidates using the last annotation releases from both CRIBI and NCBI and selected a set of genes showing positive expression patterns in targeted organs, thus lowering down the candidate gene number to 10 to 65 per QTL. None of these genes had been previously identified in QTLs for fruit size [38, 39, 76–83] or fruit acidity [75, 84, 85] in fleshy fruit crops. One of the positional candidate genes from the short list obtained is a putative cytoplasmic Malic Dehydrogenase (MDH; VIT_207s0005g03350 from CRIBI annotation, LG7). This enzyme is involved in the conversion of malate into oxaloacetate together with other isoforms in mitochondria and plastids [86–89].

In any case, this study put forward a first list of candidate genes which should be confronted with data from association genetics or transcriptomic studies for validation. Considering the number of somatic variants available for grapevine [90], mutants affected for these traits, such as the fleshless berry mutant or the reiteration of reproductive meristems mutant [38, 39] may also be used for this purpose.

The microvine: a valuable tool for QTL mapping

The Microvine or Dwarf and Rapid Cycling and Flowering (DRCF) mutant was recently proposed as a new model system for rapid forward and reverse genetics [51]. It is relevant for genetic studies on grapevine as it can be used as an annual crop, while presenting all characteristics of a perennial crop. It offers several advantages when compared to a non dwarf genotype: (1) a compact size, allowing the study of entire microvine populations under controlled environment, (2) an early flowering that occurs in the same year as sowing, instead of 4–6 years with the non DRCF genotypes, and (3) a continuous production of reproductive organs with sequential ripening allowing the study of all the development stages at the same time or at several times during the year. Such a sequential ripening along the shoot is known to occur in non-DRCF vines as well [91]. These characteristics are ideal to prospect the genetic and ecophysiological bases of grapevine adaptation to abiotic stresses, since microvine berry development exhibits the same pattern as regular vine [45, 92, 93]. Using microvine progenies and high throughput microarrays screening, Fernandez et al. [38] were able to map the fleshless berry locus and to identify a mutation in VvPI as the origin of the fleshless berry phenotype. Moreover, Dunlevy et al. [94] used a F2 progeny of a cross between a DRCF mutant, which does not produce 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine (IBMP), and the V. vinifera Cabernet Sauvignon cv., to identify the major locus responsible for accumulation of IBMP in grapes.

Microvine was used in the present study to decipher the genetic control of quantitative traits related to plant vegetative and reproductive development. The microvine population, obtained from a cross between a Picovine x Ugni Blanc flb, allowed the phenotyping of up to 43 traits under nine environmental conditions. However, to obtain a large microvine mapping population, the use of the Picovine as a female parent was required, because it is homozygous for the dwarf mutation (Vvgai1) and female loci [51]. The high homozygosity of the Picovine 00C001V0008 genome, resulted in only half a maternal genetic map, with an entire linkage group missing (LG 7). Thus, the identification of QTLs for this parent was not exhaustive.

The grapevine 18 K SNP chip

The 18 K SNP chip allowed building both high-quality and high-density genetic maps. Indeed, the overall genotyping error rate was ≤ 0.0005 for each map, and only 167 out of the 18,071 SNPs present on the chip were discarded due to segregation distortion issues. In addition, reproducibility of control genotypes used for the chip creation was 100 %, when the DNA analysed was of good quality (A. Launay, personal communication). This was the case for all the samples in the present study. Such a very low error rate is an advantage of this high-throughput technique when compared to bar-coded multiplex sequencing [95] or Genotyping By Sequencing [96], which produce huge amounts of data but with a high rate of genotyping error.

The two high-density parental genetic maps contained 408 and 714 SNP markers with an average distance of 1.8 and 1.5 cM for Picovine and Ugni Blanc flb, respectively. The marker coverage of these genetic maps is higher than in most recent studies using AFLP, SSR and/or SNP markers in grapevine. The latest studies reported an average interval between adjacent markers from 1.9 to 7.3 cM for genetic maps with less than 300 markers per map [25, 34, 66, 82, 97–100]. The map of Vezzulli et al. [49] was based on 1,134 markers with an average spacing of 1.3 cM, but it resulted from the integration of maps from three different populations. Recently, Wang et al. [101] and Barba et al. [36], using next generation sequencing, reported parental maps of 759–1,121 SNP markers with inter-marker distances of 1.7-2.3 cM and a consensus map of 1,215 SNP markers distant of 1.6 cM on average, respectively. Recently, Chen et al. [71] also reported two parental maps with intervals ranging from 2.0 to 2.5 cM, by genotyping an interspecific Vitis hybrid with next-generation restriction site-associated DNA sequencing.

Here, the high average map density achieved was fully satisfying since maps were saturated with many co-segregating SNP markers, despite the low proportion of informative markers (6,000 out of 18 K) in the mapping population. In previous studies using high-throughput Illumina® SNP chip genotyping for QTL or association genetics in rice, alfalfa, maize and wheat [102–105], the proportion of polymorphic markers was larger, ranging from 52 % to 81 %. The 18 K grapevine SNP chip was composed of 13,561 SNPs (75 %) from 47 Vitis vinifera and 4,510 SNPs (25 %) from 13 other Vitis species and Muscadinia rotundifolia [106] while 96 % of the 6,000 SNPs polymorphic in the mapping population were from V. vinifera. This discrepancy partly explained the low proportion of SNPs that could be used for mapping in this population. Within the Vitis genus, species are clearly differentiated [107] and SNP transferability to V. vinifera is low [108]. In spite of the technical constraints for the design of specific probes [106], there were only two regions not covered with V. vinifera SNP markers on the chip, corresponding to the bottom of chromosome 9 (about 8.9 Mb) and to an inferior part of chromosome 3 (about 4.4 Mb) (A. Launay, personal communication). The technical constraints, together with the low polymorphism levels of non-vinifera SNP markers in this population could explain the few gaps observed in parental maps, their occurrence being further increased for Picovine due to its high homozygosity.

Conclusions

Applying an abiotic stress on a whole population for genetic studies is particularly difficult for a perennial crop such as grapevine. Thanks to the reduced size of the microvine and its biological characteristics, we were able to grow a progeny of microvines under several environmental conditions, mainly differing in temperature. In this study, we identify some new QTLs for important developmental vegetative and reproductive traits that have limited interactions with environmental factors such as temperature. Therefore, these QTLs are a valuable first step towards finding useful genetic variation for maintaining vine yield and fruit quality under elevated temperatures.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The present study was performed at Montpellier SupAgro-INRA campus (France) on a pseudo-F1 microvine population from 2011 to 2014. The latter was obtained from a cross between the Picovine 00C001V0008 (Vvgai1/Vvgai1), which confers to the progeny Dwarf and Rapid Cycling and Flowering (DRCF) traits [51], and the grapevine Ugni Blanc fleshless berry mutant (flb; [52]). Only hermaphrodite individuals bearing wild type (non-fleshless) berries were retained, resulting in the selection of 129 microvine offspring in this progeny. In addition to the dwarf stature, an interesting biological property of the microvine is the continuous production of inflorescences along all the vegetative axes straight from the first year of development (Fig. 3a), with sequential ripening along the shoot [45, 92]. Several copies of each individual of this progeny were established in 3 L pots filled with Neuhauss Humin-substrate N2 (Klasmann-Deilmann, Bourgoin Jallieu, France). Three year-old plants were used for a better balance between root and above ground organ developments. Plants were spur-pruned to 2–4 buds. Then, a single proleptic axis was kept per plant close after budburst, in order to synchronize development between plants (Fig. 3a). Sylleptic axes were removed as soon as they appeared to reduce crop load. At budburst, 15 g of Osmocote exact standard fertilizer (Everris, Limas, France) were added. Non-limiting irrigation was supplied during the whole plant cycle (Fig. 3b). One copy of the population was grown in a greenhouse and two copies were grown outdoors in two complete blocks. In order to identify stable QTLs across more varied thermal growth conditions, two copies were also grown in growth rooms under controlled environments, during one month. Temperature treatments were 20°/15 °C and 30°/25 °C (day/night) for “cool” and “hot” treatment, respectively. Each treatment was applied to a single copy of the population. A 14-h photoperiod was imposed. In the growth rooms, mean Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) was maintained between 0.7 and 1.8 kPa during photoperiod and average daily Photosynthetic Active Radiation (PAR) per day was around 20–25 mol.m−2. The different climatic conditions during plant growth are summarized for all environments in Additional file 11.

Phenotypic variables

Forty-three traits (five vegetative traits and 38 reproductive traits; Table 1) were either directly measured or inferred from direct measurements, on one copy of the population in the greenhouse in 2011, on one copy (2011) and two copies (2012, 2013 and 2014) outdoors, and on two copies in growth rooms in 2013 and 2014 (Table 1).

Vegetative traits

Budburst time (stage EL4; [109]) was determined from cumulated growing degree-day (GDD) after March 15th. GDD was calculated as the difference between the average of the daily temperatures and the base temperature (Tbase = 10 °C; [110]). The number of unfolded leaves per vine was counted twice a week for two months in the greenhouse and outdoors, and during the whole experiment (one month) in growth rooms. The leaf emergence rate was calculated from linear regression between the cumulated GDDs after budburst and the number of leaves. The phyllochron (PHY), or GDD required between the emergence of two successive leaves, was the reverse of the leaf emergence rate. Leaf area (LA) was calculated from leaf main vein length measurements. Specific allometric relationships between the above variables were parameterized for each genotype from measurements on seven leaves of constrasted plastochron index, using ImageJ version 1.43 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Six leaf disks of 1 cm diameter were sampled on each plant and dried at 70 °C for 72 h to determine leaf mass per area (LMA). The internode length (IL) was calculated at the end of the experiments as the whole proleptic axis height divided by the number of phytomers in the greenhouse and outdoors, or just considering unfolded phytomers during temperature treatments in growth rooms.

Reproductive traits

The number of pre-formed basal inflorescences (i.e. inflorescences differentiated within winter buds) per plant (NBI) and the position of the first pre-formed inflorescence (PBI) on the main proleptic axis were noted. The pre-formed basal inflorescences could be distinguished from the neo-formed ones, because they were larger, with more branching and more flowers and located at ranks 3 to 6 on the proleptic axis. Basal inflorescences were removed after flowering to avoid a competition with neo-formed inflorescences. The period from inflorescence appearance (stage 51 according to BBCH international scale; [111]) to 50 % flowering (stage 65) (PIF) and from 50 % flowering to 50 % véraison (stage 85) (PFV) were observed on three neo-formed clusters per plant. All the berries of two clusters were sampled at two developmental stages at the herbaceous plateau and 40 days after the onset of ripening, thereafter called ‘green lag phase’ and ‘maturity stage’, respectively. The continuous reproductive development and sequential ripening along the main axis of microvine plants allowed an accurate assessment of the onset of ripening, characterized by berry softening. Berries just prior to this stage, on the former younger phytomer, were considered to be at the ‘green lag phase’. For the ‘maturity stage’, inflorescences were tagged at the onset of ripening and sampled 40 days later. Two inflorescences per plant were tagged in the greenhouse and outdoors, and only one inflorescence per plant was tagged in growth rooms. At green lag phase and maturity stages, the berry fresh weight of seeded berries was recorded (BWG, BWM). At maturity, the total number of berries per cluster was counted, including seeded and seedless berries. Number of seeds (NS) and seed fresh weight (SW) were determined in seeded berries only. The number of clusters along ten successive phytomers (NC) was also recorded.

Berry biochemistry

Berries were randomly sampled at green lag phase and maturity stage. Depending on cluster size, 15 to 20 berries were crushed and diluted 5-fold in deionized water prior to freezing at −20 °C. For organic acids, glucose and fructose analyses, samples were thawed at room temperature and subsequently heated at 60 °C for 30 min. After return to room temperature, samples were homogenized and an aliquot was diluted 10 to 20 folds in 4.375 μM acetic acid (internal standard). To avoid potassium bi-tartrate precipitation and to reduce the area of the injection peak, 1 mL sample was mixed with 0.18 g of Sigma Amberlite® IR-120 Plus (sodium form), and agitated on a rotary shaker for at least ten hours before centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) vials before injection on an Aminex HPX®87H column eluted in isocratic conditions (0.5 mL.min−1, 60 °C, 0.5 g.L-1 of H2SO4) [112]. Organic acids were detected at 210 nm with a Waters 2487 dual absorbance detector® (Waters Corporation, Massachusetts, United States). A refractive index detector Kontron 475® (Kontron Instruments, Switzerland) was used to determine fructose and glucose concentrations. Concentrations were calculated according to Eyegghe-Bickong et al. [113] for deconvolution of fructose and malic acid, after checking the validity of this procedure on tartaric acid, malic acid, glucose and fructose standards, either in pure or mixed solutions. Several ratios between the biochemical components were also calculated (Table 1).

Phenotypic data analyses

Phenotypic data were analysed using the R software version 2.15.0 [114]. Data were clustered using the Ward method as described in Houel et al. [54], in order to assess correlations between all traits for each growing condition. Normality of the distribution was tested for each trait, using the Shapiro-Wilk test [115]. When data distribution deviated from normality, a Box-Cox transformation [116] was applied to unskew the distribution. When trait data were available for two copies in a given environment, the full and sub-mixed linear models were adjusted using the lme4 package [117]. Then, the best-fit model was selected using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The full model was Y ij = μ + G i + c j + E ij, where Y ij was the phenotypic trait for copy j of genotype i, μ the general mean, G i the random effect of genotype i, c j the fixed effect of copy j and E ij the random residual term. The best linear unbiased predictors (BLUPs) of genetic values were extracted for QTL detection when there were two copies. The genotype and residual variance estimates (σ 2 G and σ 2 E, respectively) were used to estimate broad sense heritability (H 2) of the inter-environment genotypic mean as σ 2 G/(σ 2 G + σ 2 E), allowing for the possible addition of a fixed environment effect to the model. The assumption of normality of residual and BLUP distributions was checked through quantile-quantile plots comparing the observed distributions to a theoretical normal distribution.

DNA extraction, SNP marker genotyping and marker selection

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) was extracted from 1 g of young leaves (with main rib less than 2 cm long) using DNeasy Plant Maxi Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of the DNA were checked using the Agilent® 2100 bioanalyzer system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The population was genotyped using the Illumina® 18 K SNP Infinium chip (18,071 SNP markers; [106]). Results were visualized and manually edited when necessary using the Illumina® Genome Studio software version 2011.1 [118]. The SNP markers that were monomorphic (55 % of the total markers), multilocus or with an ambiguous pattern (8 %), highly distorted or with a minor allele frequency < 10 % (1 %), were discarded. The remaining 6,000 SNP markers passing these filters were used to build the genetic maps, out of which 2,727 and 4,284 were heterozygous in Picovine and Ugni Blanc flb, respectively.

Linkage map construction

For each parent, a framework linkage map of reliable order was constructed using CarthaGene version 1.0 [119], based on the most informative SNPs among the 6,000 usable ones. A LOD threshold of 4 and a distance threshold of 30 cM were used to identify linkage groups (LG). The grouping was also adjusted using the knowledge about physical genome map. The most likely marker order within each LG was determined using the stepwise marker insertion command “buildfw” (with 2, 0.2 and 1 for the Keep threshold, Add threshold and Mrktest arguments, respectively). This procedure yields a framework map by automatically selecting a subset of markers to ensure a reliable order. This order was then optimized using a taboo technique (“greedy” command with 3, 1, 1 and 15 for NbLoop, Fuel, TabooMin and TabooMax arguments, respectively). Finally, all possible permutations within a sliding window were applied to the best map obtained (“flips” command with 5, 2 and 1 for Size, LOD-threshold and Iterative arguments, respectively), to detect any better local order. The order and quality of the two genetic maps were then checked using the R package qtl [120], following the tutorial’s instructions [121]. The overall genotyping error rate was estimated within the 0.0005-0.05 range, the “checkalleles” function was used to detect markers with erroneous linkage phases and the “droponemarker” function to spot suspicious markers.

QTL detection

QTL detection was performed in each parental map on the genotypic BLUPs when available for two copies or directly on transformed data, using the R qtl package. Multiple QTL regression was carried out with the "stepwiseqtl" function, as described by Huang et al. [32]. This approach is based on forward/backward selection to compare several multiple-QTL models with main effect QTLs and possible pairwise QTLxQTL interactions. To select the QTL model, specific penalties were applied to the LOD score according to the number of main effects and interaction terms. For each trait, these penalties were derived from 1000 permutations with a two-dimensional scan and a genome-wide error rate of 0.05. Genome scan was performed with a 1 cM step. LOD-1 QTL location confidence intervals were derived with the “lodint” function.

Candidate genes for QTLs

When necessary, the confidence interval was first reduced to ±3 cM around the LOD peak of each QTL in each environment, in order to focus on the most probable location of the causative polymorphism [122]. Then, when the confidence intervals of a QTL in different growing conditions overlapped, the candidate genes were searched within the most extreme limits of the corresponding set of reduced overlapping intervals, thereafter referred to as the integrated interval. The physical coordinates of integrated interval limits on the latest version of the PN40024 reference genome sequence (assembly version 12X.2; [123]) were deduced from local recombination rate between flanking SNP markers with known physical coordinates [106]. Two public annotations of the genome were considered in order to maximize the chances to identify candidate genes: the latest CRIBI version 2 [124, 125] and the classical REFSEQ version 1 from NCBI [126], that both refer to the 12X.0 genome sequence. The gene coordinates in the CRIBI and the NCBI General Feature Format (GFF) files were corrected to take into account (1) scaffold rearrangements between PN40024 12X.0 and 12X.2 versions and (2) the insertion of 500 n between scaffolds in the CRIBI annotation that is absent in the NCBI one. All the coordinates given in the present paper refer to the PN40024 reference genome sequence assembly version 12X.2. As a first approach, based on this exhaustive list of positional genes, we performed a two-step selection to reduce the number of candidates per QTL. A list of the biological functions most probably associated with the identified QTL traits was established based on our own expertise and literature data [4, 127, 128] (Additional file 8). In this respect, the genes were selected according to the Gene Ontology available in the GFF files from both annotations. Lastly, the expression pattern of candidate genes in different organs and developmental stages of grapevine was retrieved from Fasoli et al. [129] in order to screen genes expressed in the organs linked to the traits for which QTLs were found.

Abbreviations

- ASKG:

-

Total acids, sugars and potassium at green lag phase

- ASKM:

-

Total acids, sugars and potassium at maturity

- BB:

-

Budburst time

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- BLUP:

-

Best Linear Unbiased Predictor

- BWG:

-

Berry weight at green lag phase

- BWM:

-

Berry weight at maturity

- CiG:

-

Citrate at green lag phase

- CiM:

-

Citrate at maturity

- COG:

-

Citrate/total acids ratio at green lag phase

- COM:

-

Citrate/total acids ratio at maturity

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- DRCF:

-

Dwarfism, Rapid and Continuously Fruiting phenotype

- FuG:

-

Fructose at green lag phase

- FuM:

-

Fructose at maturity

- GDD:

-

Growing Degree Day

- GFG:

-

Glucose/fructose ratio at green lag phase

- GFM:

-

Glucose/fructose ratio at maturity

- GFF:

-

General Feature Format

- GuG:

-

Glucose at green lag phase

- GuM:

-

Glucose at maturity

- HPLC:

-

High Performance Liquid Chromatography

- IL:

-

Internode length

- KG:

-

Potassium at green lag phase

- KM:

-

Potassium at maturity

- LG:

-

Linkage Group

- LA:

-

Leaf area

- LMA:

-

Leaf mass per area

- MaG:

-

Malate at green lag phase

- MaM:

-

Malate at maturity

- MOG:

-

Malate/total acids ratio at green lag phase

- MOM:

-

Malate/total acids ratio at maturity

- MTG:

-

Malate/tartrate ratio at green lag phase

- MTM:

-

Malate/tartrate ratio at maturity

- NB:

-

Number of berries per cluster at maturity

- NBI:

-

Number of pre-formed inflorescences in winter buds per plant

- NC:

-

Number of clusters per ten phytomers at maturity

- NS:

-

Number of seeds per berry at maturity

- PAR:

-

Photosynthetic Active Radiation

- PBI:

-

Position of first pre-formed inflorescence

- PHY:

-

Phyllochron

- PFV:

-

Period from 50 % flowering to 50 % véraison

- PIF:

-

Period from inflorescence appearance to 50 % flowering

- QTL:

-

Quantitative Trait Locus

- SNP:

-

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- SW:

-

Seed weight at maturity

- TaG:

-

Tartrate at green lag phase

- TaM:

-

Tartrate at maturity

- ToAG:

-

Total acids at green lag phase

- ToAM:

-

Total acids at maturity

- TOG:

-

Tatrate/total acids ratio at green lag phase

- TOM:

-

Tatrate/total acids ratio at maturity

- ToSG:

-

Total sugars at green lag phase

- ToSM:

-

Total sugars at maturity

- VPD:

-

Vapour Pressure Deficit

References

Webb LB, Whetton PH, Barlow EWR. Climate change and winegrape quality in Australia. Clim Res. 2008;36:99–111.

IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2013. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.

Jones GV, Davis RE. Climate influences on grapevine phenology, grape composition, and wine production and quality for Bordeaux. France Am J Enol Vitic. 2000;51:249–61.

Keller M. The science of grapevines: Anatomy and physiology. London, Great Britain: Elsevier Academic Press; 2010.

Soar CJ, Dry PR, Loveys BR. Scion photosynthesis and leaf gas exchange in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Shiraz: Mediation of rootstock effects via xylem sap ABA. Aust J Grape Wine R. 2006;12:82–96.

Hannah L, Roehrdanz PR, Ikegami M, Shepard AV, Shaw MR, Tabor G, et al. Climate change, wine, and conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6907–12.

Jones GV, White MA, Storchmann K. Climate Change and Global Wine Quality. Clim Change. 2005;76:319–43.

Duchêne E, Schneider C. Grapevine and climatic changes: a glance at the situation in Alsace. Agron Sustain Dev. 2005;25:93–9.

Champagnol F. Éléments de physiologie de la vigne et de viticulture générale. Saint-Gély-du-Fesc, France: Champagnol Ed; 1984.

Schultz H. Climate change and viticulture: A European perspective on climatology, carbon dioxide and UV-B effects. Aust J Grape Wine R. 2000;6:2–12.

Spayd SE, Tarara JM, Mee DL, Ferguson JC. Separation of sunlight and temperature effects on the composition of Vitis vinifera cv. merlot berries. Am J Enol Vitic. 2002;53:171–82.

Tarara JM, Lee J, Spayd SE, Scagel CF. Berry temperature and solar radiation alter acylation, proportion, and concentration of anthocyanin in merlot grapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2008;59:235–47.

Neethling E, Barbeau G, Bonnefoy C, Quénol H. Change in climate and berry composition for grapevine varieties cultivated in the Loire Valley. Clim Res. 2012;53:89–101.

Jones GV, Alves F. Impact of climate change on wine production: a global overview and regional assessment in the Douro Valley of Portugal. Int J Global Warm. 2012;4:383–406.

Pugliese M, Gullino ML, Garibaldi A. Effect of climate change on infection of grapevine by downy and powdery mildew under controlled environment. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2011;76:579–82.

Field SK, Smith JP, Holzapfel BP, Hardie WJ, Emery RJN. Grapevine Response to Soil Temperature: Xylem Cytokinins and Carbohydrate Reserve Mobilization from Budbreak to Anthesis. Am J Enol Vitic. 2009;60:164–72.

Greer DH, Weston C. Heat stress affects flowering, berry growth, sugar accumulation and photosynthesis of Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon grapevines grown in a controlled environment. Funct Plant Biol. 2010;37:206–14.

Malheiro AC, Santos JA, Fraga H, Pinto JG. Climate change scenarios applied to viticultural zoning in Europe. Clim Res. 2010;43:163–77.

Fraga H, Malheiro AC, Moutinho-Pereira J, Santos JA. An overview of climate change impacts on European viticulture. Food and Energy Security. 2012;1:94–110.

Greer DH, Weston C, Weedon M. Shoot architecture, growth and development dynamics of Vitis vinifera cv. Semillon vines grown in an irrigated vineyard with and without shade covering. Funct Plant Biol. 2010;37:1061–70.

Ollat N, Fernandez L, Lecourieux D, Goutouly J-P, van Leeuwen K, Marguerit E, et al. Multidisciplinary research to select new cultivars adapted to climate changes. Asti-Alba, Italy: 17th International Symposium of GiESCO; 2011.

Van Leeuwen C, Schultz HR. Garcia de Cortazar-Atauri I, Duchêne E, Ollat N, Pieri P, et al. Why climate change will not dramatically decrease viticultural suitability in main wine-producing areas by 2050. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3051–2.

Ollat N, Bordenave L, Marguerit E, Tandonnet J-P, van Leeuwen K, Destrac A, et al. Grapevine genetic diversity, a key issue to cope with climate change. Beijing, China: 11th International Conference of Grape Genetics & Breeding; 2014.

Costantini L, Battilana J, Lamaj F, Fanizza G, Grando MS. Berry and phenology-related traits in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): From Quantitative Trait Loci to underlying genes. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:38.

Doligez A, Bertrand Y, Farnos M, Grolier M, Romieu C, Esnault F, et al. New stable QTLs for berry weight do not colocalize with QTLs for seed traits in cultivated grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:217.

Fanizza G, Lamaj F, Costantini L, Chaabane R, Grando MS. QTL analysis for fruit yield components in table grapes (Vitis vinifera). Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111:658–64.

Duchêne E, Butterlin G, Dumas V, Merdinoglu D. Towards the adaptation of grapevine varieties to climate change: QTLs and candidate genes for developmental stages. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124:623–35.

Grzeskowiak L, Costantini L, Lorenzi S, Grando MS. Candidate loci for phenology and fruitfulness contributing to the phenotypic variability observed in grapevine. Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:2763–76.

Doligez A, Audiot E, Baumes R, This P. QTLs for muscat flavor and monoterpenic odorant content in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Mol Breed. 2006;18:109–25.

Emanuelli F, Battilana J, Costantini L, Le Cunff L, Boursiquot J-M, This P, et al. A candidate gene association study on muscat flavor in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:241.

Fournier-Level A, Le Cunff L, Gomez C, Doligez A, Ageorges A, Roux C, et al. Quantitative genetic bases of anthocyanin variation in grape (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. sativa) berry: a quantitative trait locus to quantitative trait nucleotide integrated study. Genetics. 2009;183:1127–39.

Huang YF, Doligez A, Fournier-Level A, Le Cunff L, Bertrand Y, Canaguier A, et al. Dissecting genetic architecture of grape proanthocyanidin composition through quantitative trait locus mapping. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:30.

Doligez A, Bertrand Y, Dias S, Grolier M, Ballester J, Bouquet A, et al. QTLs for fertility in table grape (Vitis vinifera L.). Tree Genet Genomes. 2010;6:413–22.

Correa J, Mamani M, Muñoz-Espinoza C, Laborie D, Muñoz C, Pinto M, et al. Heritability and identification of QTLs and underlying candidate genes associated with the architecture of the grapevine cluster (Vitis vinifera L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:1143–62.

Venuti S, Copetti D, Foria S, Falginella L, Hoffmann S, Bellin D, et al. Historical introgression of the downy mildew resistance gene Rpv12 from the Asian species Vitis amurensis into grapevine varieties. PLoS One. 2013;8, e61228.

Barba P, Cadle-Davidson L, Harriman J, Glaubitz JC, Brooks S, Hyma K, et al. Grapevine powdery mildew resistance and susceptibility loci identified on a high-resolution SNP map. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:73–84.

Carmona MJ, Chaib J, Martinez-Zapater JM, Thomas MR. A molecular perspective of reproductive developement in grapevine. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:2579–96.

Fernandez L, Chaïb J, Martinez-Zapater JM, Thomas MR, Torregrosa L. Mis-expression of a PISTILLATA-like MADS box gene prevents fruit development in grapevine. Plant J. 2013;73:918–28.

Fernandez L, Le Cunff L, Tello J, Lacombe T, Boursiquot JM, Fournier-Level A, et al. Haplotype diversity of VvTFL1A gene and association with cluster traits in grapevine (V. vinifera). BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:209.

Debolt S, Cook DR, Ford CM. L-tartaric acid synthesis form vitamin C in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;1003:5608–13.

Terrier N, Torregrosa L, Vialet S, Ageorges A, Verries C, Cheynier V, et al. Ectopic expression of VvMybPA2 promotes proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Vitis vinifera L. and reveals additional putative actors of the pathway. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:108–31.

Cutanda-Perez MC, Ageorges A, Gomez C, Vialet S, Romieu C, Torregrosa L. Ectopic expression of the VlmybA1 in grapevine activates a narrow set of genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis and transport. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69:633–48.

Gomez C, Terrier N, Torregrosa L, Vialet S, Fournier-Level A, Verries C, et al. Vitis vinifera MATE-type Proteins Act as Vacuolar H + −Dependent Acylated Anthocyanin Transporters. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:402–15.

Lecourieux F, Lecourieux D, Vignault C, Delrot S. A sugar-inducible protein kinase, VvSK1, regulates hexose transport and sugar accumulation in grapevine cells. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1096–106.

Luchaire N, Rienth M, Nehe A, Torregrosa L, Romieu C, Muller B, et al. The Microvine: An ecophysiological model for grapevine. 18th International Symposium of GiESCO, Porto, Portugal, 7–11 July 2013. https://colloque.inra.fr/giesco-2015_eng/Media/Fichier/EXAMPLE-OF-ARTICLE-FORMAT-2015-V10-2015-1-20.

Rienth M, Luchaire N, Chatbanyong R, Agorges A, Kelly M, Brillouet JM, et al. The microvine provides new perspectives for research on berry physiology. In: proceedings of the GiESCO 2013. Porto, Portugal: Ciencia e Tecnica Vitivinicola; 2013. p. 412–17.

Marguerit E, Brendel O, Lebon E, Van Leeuwen C, Ollat N. Rootstock control of scion transpiration and its acclimation to water deficit are controlled by different genes. New Phytol. 2012;194:416–29.

Coupel-Ledru A, Lebon E, Christophe A, Doligez A, Cabrera-Bosquet L, Péchier P, et al. Genetic variation in a grapevine progeny (Vitis vinifera L. cvs Grenache × Syrah) reveals inconsistencies between maintenance of daytime leaf water potential and response of transpiration rate under drought. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:6205–18.

Vezzulli S, Troggio M, Coppola G, Jermakow A, Cartwright D, Zharkikh A, et al. A reference integrated map for cultivated grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) from three crosses, based on 283 SSR and 501 SNP-based markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;117:499–511.

Bergamini C, Cardone MF, Anaclerio A, Perniola R, Pichierri A, Genghi R, et al. Validation assay of p3_VvAGL11 marker in a wide range of genetic background for early selection of stenospermocarpy in Vitis vinifera L. Mol Biotechnol. 2013;54:1021–30.

Chaib J, Torregrosa L, Mackenzie D, Corena P, Alain Bouquet A, Thomas MR. The grape microvine: a model system for rapid forward and reverse genetics of grapevines. Plant J. 2010;62:1083–92.

Fernandez L, Romieu C, Moing A, Bouquet A, Maucourt M, Thomas MR, et al. The grapevine fleshless berry mutation: A unique genotype to investigate differences between fleshy and non-fleshy fruit. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:537–47.

Marguerit E, Boury C, Manicki A, Donnart M. Butterlin, Nemorin A, et al. Genetic dissection of sex determinism, inflorescence morphology and downy mildew resistance in grapevine. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;118:1261–78.

Houel C, Martin-Magniette M-L, Nicolas N, Lacombe T, Le Cunff L, Franck D, et al. Genetic variability of the berry size in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Aust J Grape Wine R. 2013;19:208–20.

Terrier N, Romieu C. Grape berry acidity. I. In: Angelakis R, editor. Molecular biology and biotechnology of the grapevine. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011.

Liu HF, Wu BH, Fan PG, Xu HY, Li SH. Inheritance of sugars and acids in berries of grape (Vitis vinifera L.). Euphytica. 2007;153:99–107.

Sestras R, Moldovan SD, Popescu CF. Variability and Heritability of Several Important Traits for Grape Production and Breeding. Not Bot Hort Agrobot Cluj. 2008;36:88–97.

Firoozabady E, Olmo HP. Heritability and correlation studies of certain quantitative traits in table grapes, Vitis spp. Vitis. 1987;26:132–46.

Daulta BS, Bakhshi JC, Chandra S. Evaluation of vinifera varieties for genotypic and phenotypic variability. Indian J Hortic. 1972;29:150–7.

Golodriga PI, Trochine LP. Héritabilité des caractères quantitatifs chez la vigne. In: Proceedings of the IInd Symposium on Grape Genetics and Breeding. 1978. p. 113–7.

Singh R, Jalikop SH. Studies on variability in grape. Indian J Hortic. 1986;43:207–15.

Rasoli V, Farshadfar E, Ahmadi J. Genetic contribution of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) main yield components in final yield. Int J Adv Biol Biom Res. 2014;2:2774–8.

Doligez A, Bouquet A, Danglot Y, Lahogue F, Riaz S, Meredith P, et al. Genetic mapping of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) applied to the detection of QTLs for seedlessness and berry weight. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105:780–95.

Cabezas JA, Cervera MT, Ruiz-García L, Carreño J, Martínez-Zapater JM. A genetic analysis of seed and berry weight in grapevine. Genome. 2009;49:1572–85.

Mejía N, Gebauer M, Muñoz L, Hewstone N, Muñoz C, Hinrichsen P. Identification of QTLs for Seedlessness, Berry Size, and Ripening Date in a Seedless x Seedless Table Grape Progeny. Am J Enol Vitic. 2007;58:499–507.

Viana AP, Riaz S, Walker MA. Genetic dissection of agronomic traits within a segregating population of breeding table grapes. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:951–64.

Blouin J. Guimberteau G. Editions Féret: Maturation et maturité des raisins; 2000.

Barnuud NN, Zerihun A, Gibberd M, Bates B. Berry composition and climate: responses and empirical models. Int J Biometeorol. 2014;58:1207–23.

Barnuud NN, Zerihun A, Mpelasoka F, Gibberd M, Bates B. Responses of grape berry anthocyanin and titratable acidity to the projected climate change across the Western Australian wine regions. Int J Biometeorol. 2014;58:1279–93.

Duchêne E, Dumas V, Jaegli N, Merdinoglu D. Genetic variability of descriptors for grapevine berry acidity in Riesling, Gewurztraminer and their progeny. Aust J Grape Wine R. 2014;20:91–9.

Chen J, Wang N, Lin-Chuan F, Liang Z-C, Shao-Hua L, Wu B-H. Construction of a high-density genetic map and QTLs mapping for sugars and acids in grape berries. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:28.

Welter LJ, Göktürk-Baydar N, Akkurt M, Maul E, Eibach R, Töpfer R, et al. Genetic mapping and localization of quantitative trait loci affecting fungal disease resistance and leaf morphology in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L). Mol Breeding. 2007;20:359–74.

Ojeda H, Deloire A, Carbonneau A, Ageorges A, Romieu C. Berry development of grapevines: relations between the growth of berries and their DNA content indicate cell multiplication and enlargement. Vitis. 1999;38:145–50.

Bai Y, Dougherty L, Li MJ, Fazio G, Cheng LL, Xu KN. A natural mutation-led truncation in one of the two aluminum-activated malate transporter-like genes at the Ma locus is associated with low fruit acidity in apple. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012;287:663–78.

Cohen S, Itkin M, Yeselson Y, Tzuri G, Portnoy V, Harel-Baja R, et al. The PH gene determines fruit acidity and contributes to the evolution of sweet melons. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4026.

Frary A, Nesbitt TC, Grandillo S, Knaap E, Cong B, Liu J, et al. Fw2.2: a quantitative trait locus key to the evolution of tomato fruit size. Science. 2000;289:85–8.

Cong B, Lui J, Tankley SD. Natural alleles at a tomato fruit size quantitative trait locus differ by heterochronic regulatory mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13606–11.

Liu J, Van Eck J, Cong B, Tanksley SD. A new class of regulatory genes underlying the cause of pear-shaped tomato fruit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13302–6.

Tanksley SD. The genetic, developmental and molecular bases of fruit size and shape variation in tomato. Plant Cell. 2004;16:181–9.

Paran I, van der Knaap E. Genetic and molecular regulation of fruit and plant domestication traits in tomato and pepper. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:3841–52.

Xiao H, Jiang N, Schaffner E, Stockinger EJ, van der Knaap E. A retrotransposon-mediated gene duplication underlies morphological variation of tomato fruit. Science. 2008;319:1527–30.

Mejía N, Soto B, Guerrero M, Casanueva X, Houel C. de los Angeles Miccono M, et al. Molecular, genetic and transcriptional evidence for a role of VvAGL11 in stenospermocarpic seedlessness in grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:57.

Muños S, Ranc N, Botton E, Bérard A, Rolland S, Duffé P, et al. Increase in tomato locule number is controlled by two single-nucleotide polymorphisms located near WUSCHEL1. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:2244–54.

Boudehri K, Bendahmane A, Cardinet G, Troadec C, Moing A, Dirlewanger E. Phenotypic and fine genetic characterization of the D locus controlling fruit acidity in peach. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;15:59.

Aprile A, Federici C, Close TJ, De Bellis L, Cattivelli L, Roose ML. Expression of the H + −ATPase AHA10 proton pump is associated with citric acid accumulation in lemon juice sac cells. Funct Integr Genomics. 2011;11:551–63.

Taureilles-Saurel C, Romieu CG, Robin JP, Flanzy C. Grape (Vitis vinifera L) malate-dehydrogenase. 2. Characterization of the major mitochondrial and cytosolic isoforms and their role in ripening. Am J Enol Vitic. 1995;46:29–36.

Sweetman C, Deluc LG, Cramer GR, Ford CM, Soole KL. Regulation of malate metabolism in grape berry and other developing fruits. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1329–44.

Yao YX, Li M, Zhai H, You CX, Hao YJ. Isolation and characterization of an apple cytosolic malate dehydrogenase gene reveal its function in malate synthesis. J Plant Physiol. 2011;168:474–80.

Etienne A, Genard M, Lobit P, Mbeguie A, Mbeguie D, Bugaud C. What controls fleshy fruit acidity? A review of malate and citrate accumulation in fruit cells. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:1451–69.

Torregrosa L, Fernandez L, Bouquet A, Boursiquot JM, Pelsy F, Martinez-Zapater JM. Origins and Consequences of Somatic Variation in Grapevine. In: “Genetics, genomics and Breeding of Grapes”. Enfield, New Hampshire, USA: Kole C ED, Science publishers; 2011. doi:10.1201/b10948-4.

Coombe BG, McCarthy MG. Dynamics of grape berry growth and physiology of ripening. Aust J Grape Wine R. 2000;6:131–5.

Rienth M, Torregrosa L, Kelly M, Luchaire N, Grimplet J, Romieu C. The transcriptomic control of berry development is more important at Night than at Day. Plos One. 2014;9, e88844.

Rienth M, Torregrosa L, Luchaire N, Chatbanyong R, Lecourieux D, Kelly MT, et al. Day and night heat stress trigger different transcriptomic responses in green and ripening grapevine (Vitis vinifera) fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:108.

Dunlevy JD, Dennis EG, Soole KL, Perkins MV, Davies C, Boss PK. A methyltransferase essential for the methoxypyrazine derived flavour of wine. Plant J. 2013;75:606–17.

Xie W, Feng Q, Yu H, Huang X, Zhao Q, Xing Y, et al. Parent-independent genotyping for constructing an ultrahigh-density linkage map based on population sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10578–83.

Mardis ER. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends Genet. 2008;24:133–41.

Blanc S, Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S, Dumas V, Mestre P, Merdinoglu D. A reference genetic map of Muscadinia rotundifolia and identification of Ren5, a new major locus for resistance to grapevine powdery mildew. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;125:1663–75.

Blasi P, Blanc S, Wiedemann-Merdinoglu S, Prado E, Rühl EH, Mestre P, et al. Construction of a reference linkage map of Vitis amurensis and genetic mapping of Rpv8, a locus conferring resistance to grapevine downy mildew. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:43–53.

Schwander F, Eibach R, Fechter I, Hausmann L, Zyprian E, Töpfer R. Rpv10: a new locus from the Asian Vitis gene pool for pyramiding downy mildew resistance loci in grapevine. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124:163–76.

Bert PF, Bordenave L, Donnart M, Hévin C, Ollat N, Decroocq S. Mapping genetic loci for tolerance to lime-induced iron deficiency chlorosis in grapevine rootstocks (Vitis sp.). Theor Appl Genet. 2013;126:451–73.

Wang N, Fang L, Xin H, Wang L, Li S. Construction of a high-density genetic map for grape using next generation restriction-site associated DNA sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:148.

Tan C, Han Z, Yu H, Zhan W, Xie W, Chen X, et al. QTL scanning for rice yield using a whole genome SNP array. J Genet Genomics. 2013;40:629–38.

Gurung S, Mamidi S, Bonman JM, Xiong M, Brown-Guedira G, Adhikari TB. Genome-wide association study reveals novel quantitative trait Loci associated with resistance to multiple leaf spot diseases of spring wheat. PLoS One. 2014;9, e108179.

Wang S, Wong D, Forrest K, Allen A, Chao S, Huang BE, et al. Characterization of polyploid wheat genomic diversity using a high-density 90,000 single nucleotide polymorphism array. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12:787–96.

Wu X, Li Y, Shi Y, Song Y, Wang T, Huang Y, et al. Fine genetic characterization of elite maize germplasm using high-throughput SNP genotyping. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127:621–31.

Le Paslier M-C, Choisne N, Scalabrin S, Bacilieri R, Berard A, Bounon R, et al. The GrapeReSeq 18 K Vitis genotyping chip. Ninth International Symposium on Grapevine Physiology & Biotechnology, La Serena, Chili, 21–26 April 2013. https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/About-us/Team/Genome-analysis/Nathalie-Choisne/THE-GRAPERESEQ-18K-VITIS-GENOTYPING-CHIP.

Péros JP, Berger G, Portemont A, Boursiquot JM, Lacombe T. Genetic variation and biogeography of the disjunct Vitis subg. Vitis (Vitaceae). J Biogeogr. 2011;38:471–86.

Vezzulli S, Micheletti D, Riaz S, Pindo M, Viola R, This P, et al. A SNP transferability survey within the genus Vitis. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:128.

Coombe BG. Growth Stages of the Grapevine. Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Aust J Grape Wine R. 1995;1:104–10.

Winkler AJ, Cook JA, Kliewer WM, Lider LA. General viticulture. Berkeley: University of California; 1974. doi:10.1097/00010694-197512000-00012.

Lorenz DH, Eichhorn KW, Blei-Holder H, Klose R, Meier U, Weber E. Phänologische Entwicklungsstadien der Weinrebe (Vitis vinifera L.: ssp. vinifera). Vitic Enol Sci. 1994;49:66–70.

Schneider A, Gerbi V, Redoglia M. A rapid HPLC method for separation and determination of major organic acids in grape musts and wine. Am J Enol Vitic. 1987;38:151–5.

Eyegghe-Bickong HA, Alexandersson EO, Gouws LM, Young PR, Vivier MA. Optimisation of an HPLC method for the simultaneous quantification of the major sugars and organic acids in grapevine berries. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;885:43–9.

The R Project for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org/ (2012). Accessed 23 Sep 2013.

Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika. 1965;52:591–611.