Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus aureus is the principle causative pathogen of osteomyelitis and implant-associated bone infections. It is able to invade and to proliferate inside osteoblasts thus avoiding antibiotic therapy and the host immune system. Therefore, development of alternative approaches to stimulate host innate immune responses could be beneficial in prophylaxis against S. aureus infection. TLR9 is the intracellular receptor which recognizes unmethylated bacterial CpG-DNA and activates immune cells. Synthetic CpG-motifs containing oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODNs) mimics the stimulatory effect of bacterial DNA.

Results

Osteoblast-like SAOS-2 cells were pretreated with CpG-ODN type-A 2216, type-B 2006, or negative CpG-ODN 2243 (negative control) 4 h before infection with S. aureus isolate EDCC 5055 (=DSM 28763). Intracellular bacteria were streaked on BHI plates 4 h and 20 h after infection. ODN2216 as well as ODN2006 but not ODN2243 were able to significantly inhibit the intracellular bacterial growth because about 31 % as well as 43 % of intracellular S. aureus could survive the pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2216 or ODN2006 respectively 4 h and 20 h post-infection. RT-PCR analysis of cDNAs from SAOS-2 cells showed that pretreatment with ODN2216 or ODN2006 stimulated the expression of TLR9. Pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2216 or ODN2006 but not ODN2243 managed to induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) production inside osteoblasts as measured by flow cytometry analysis. Moreover, treating SAOS-2 cells with the antioxidant Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) obviously reduced S. aureus killing ability of TLR9 agonists mediated by oxidative stress.

Conclusions

In this work we demonstrated for the first time that CPG-ODNs have inhibitory effects on S. aureus survival inside SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cell line. This effect was attributed to stimulation of TLR9 and subsequent induction of oxidative stress. Pretreatment of infected SAOS-2 cells with ROS inhibitors resulted in the abolishment of the CPG-ODNs killing effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

S. aureus is the major pathogen causing osteomyelitis and septic arthritis [1] and highly involved in prosthetic joint infections following arthroplasty [2]. Moreover, it was established that S. aureus is able to invade and proliferate inside osteoblasts [3, 4] thus avoiding the host extracellular antibacterial weapons.

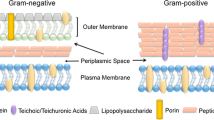

Innate immunity acts as the first active defense line against infectious pathogens and is responsible for the control of their early invasion and proliferation inside the host [5]. One of the largest and most extensively studied groups of innate immune response receptors are the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLRs are evolutionarily conserved transmembrane receptors between insects and vertebrates. They are homologues of the Drosophila Toll protein and have been established to be important for defense against microbial infection [6]. TLRs mainly recognize highly conserved structural motifs known as pathogen-associated microbial patterns (PAMPs), which are exclusively expressed by a wide variety of infectious microorganisms but not by the host. PAMPs include various bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Gram-negative bacteria, peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipopeptides of Gram-positive bacteria, as well as flagellin, unmethylated bacterial CPG-DNA and viral double-stranded RNA [7–9].

Stimulation of TLRs by the corresponding PAMPs initiates signaling cascades leading to the activation of transcription factors, such as AP-1 [10], NF-kB [11] and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) [12]. Previous studies have shown that signaling by TLRs result in a variety of cellular responses including the production of interferons (IFNs), pro-inflammatory cytokines and effector cytokines that direct the adaptive immune response [13, 14].

TLR9 is an intracellular receptor. It recognizes and is stimulated by unmethylated bacterial CpG-DNA and initiates potent cellular and humoral immune responses [13, 15]. Although TLR9 are mainly expressed in immune cells such as dendritic cells, natural killer cells, monocytes and B cells, it was also detected in osteoblasts and its role in modulating the osteoclastogenic activity of osteoblasts was reported [16].

The stimulatory effect of bacterial CpG-DNA is due to the presence of unmethylated CpG dinucleotides in a particular base context named CpG motif [15]. Bacterial genomes and vertebrate genomes are different in the frequency and methylation status of CpG dinucleotides. CpG dinucleotides in bacterial genomes generally occur at a frequency of about 1/16 as predicted by random base utilization and are unmethylated. In contrast, CpG dinucleotides in vertebrate DNA are suppressed to a frequency of only 1/50–60, almost all of which are methylated [17–19]. CpG-ODNs possess similar stimulatory effects as bacterial DNA. The CpG-DNA induces B-cell proliferation and activates cells of the myeloid lineage such as dendritic cells [15, 20, 21]. Moreover, it has been recently shown that CpG could mediate peroxide formation in cultured hepatocytes and dendritic cells resulting in an enhanced killing of intracellular Salmonella [22, 23].

Multiple studies have demonstrated that unmethylated CpG-ODNs have potent immunostimulatory effects in various immune cell subsets resulting in direct or indirect activation of NK cells, T cells, B cells, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells [23–25]. Based on these effects, CpG-ODNs act as immune adjuvants that boost antigen-specific immune responses. These effects are optimized by maintaining close physical contact between the CpG-ODN and the immunogen [26]. Co-administration of CpG-ODN with a variety of vaccines has enhanced humoral and/or cellular immune responses with subsequent stimulation of a protective immunity in various animal models of infectious diseases [27–32]. Moreover, CpG-ODNs have shown impressive effects as a single anti-cancer therapeutic agent in different animal tumor models [33–35] and can increase resistance against acute non-specific polymicrobial sepsis [36].

However, no published data are currently available about the effect of CPG-ODNs on the intracellular S. aureus survival in human osteoblasts. We have recently shown that intracellular S. aureus survival can be inhibited by antibiotics treatment such as rifampicin. The aim of the current study was to show the impact of CpG-ODNs on the expression of TLR9 in osteoblasts and if they have an inhibitory effect on the intracellular survival of S. aureus inside osteoblasts. Moreover, the mechanism of action of CpG-ODNs on the intracellular S. aureus will be demonstrated.

Methods

Bacteria

Bacterial strain used in this study is S. aureus isolate EDCC 5055 (available at DSMZ; number “DSM 28763”) [4, 37]. Bacteria were grown in brain-heart infusion (BHI) broth. In all experiments, fresh cultures of bacteria, prepared from an overnight culture, were used. Briefly, bacteria were grown in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) at 37 °C, harvested in the exponential growth phase and washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The pellet was resuspended in PBS and the bacterial concentration was calibrated by optical absorption. Further dilutions were prepared in PBS to obtain required numbers of bacteria for infection. Hemolytic activity was determined as described [37, 38].

Biofilm formation testing of S. aureus EDCC 5055 was based on the ability of the bacteria to form biofilms on polystyrene (PS) plastic, e.g. the development of microcolonies that can be detected macroscopically. Biofilm formation assay was performed as described [39]. Briefly, overnight cultures in TSB were diluted 1:100 into fresh medium and 200 μl of the freshly inoculated medium was dispensed into the wells of a microtiter plate. The inoculated microtiter plate was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h without agitation. The liquid cultures were removed and the wells were rinsed twice thoroughly and vigorously with biofilm buffer (2 mM CaCl2/MgCl2) to remove unattached cells. Two hundred microliter of biofilm buffer and 20 μl of CV staining solution (0.1 % w/v crystal violet in water) were added to detect biofilms by staining. The plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then rinsed with biofilm buffer to remove residual staining. Bacteria able to form biofilms coated the inner surface of the wells and the microcolonies were visible in purple colour.

ODNs

ODN2216 (InvivoGen) is an A-class CpG ODN with a preference for human TLR9 characterized by a phosphodiester central CpG-containing palindromic motif and a phosphorothioate 3’ poly-G string. A-class CpG ODN mainly stimulates and induces secretion of IFN-α from plasmacytoid dendritic cells [40].

ODN2006 (InvivoGen) is a CpG ODN class B specific for human TLR9. It contains a full phosphorothioate backbone with one or more CpG dinucleotides. B-class CpG ODN is a strong stimulator for B-cells [41].

ODN2243 (InvivoGen) is designed as a negative control. ODN2243 contains GpC dinucleotides instead of CpGs and does not induce TLR9 activity [42].

In vitro invasion assay of SAOS-2 cells

SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cell line was grown in Gibco Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) (Life technologies) supplemented with 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1 % non-essential amino acids. For infection assay, SAOS-2 cells were cultured to a semi confluent layer (2x105 cells/ml) in 24-well plates. Cells were treated with ODN2216, ODN2006, or ODN2243 (250 nM) (InvivoGen) 4 h prior to infection with S. aureus. 10 μM diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to ODN-pretreated cells 1 h prior to infection in order to confirm the role of oxidative stress in S. aureus intracellular survival. Bacterial cultures were incubated overnight. Following 1:10 fresh media dilution, bacterial cultures were grown for 2 h and diluted to an OD of 0.1 with MEM medium. Bacteria were added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 per well. After incubation for 30 min, supernatant was discarded and infected cells were washed twice with 1x PBS. MEM was replaced by medium supplemented with 30 μg/ml gentamicin to kill only the remaining extracellular bacteria without affecting the intracellular bacteria [43]. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 2, 4, 6 and 24 h. The supernatant fluids were discarded and the cells were washed three times with 1x PBS and lysed with 0.2 % Triton X-100 in sterile cold distilled water for 20 min after this cells were thoroughly mixed to achieve complete lysis. The lysates were diluted 10 times in 1x PBS and plated onto BHI agar plates using the Auto plate 3000 spiral plating system (Spiral Biotech, USA). After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the number of bacterial colonies were counted and the total colony forming units (cfu) were determined. In order to determine the expression of TLR9 and induction of oxidative stress in SAOS-2 cells, cells were treated with ODN2216, ODN2006, ODN2243 (250 nM) or left untreated 4 h prior to lysis for RNA isolation or collection for flow cytometry analysis.

RNA isolation

SAOS-2 cells from three wells of a six well tissue culture plaque were lysed using RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) after aspiration of the MEM medium. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit and the RNase free DNase I set (Qiagen) following the manufacturers protocol. The RNA was recovered in RNase free water, heat denatured for 10 min. at 65 °C; quantified with the NanoDrop® ND-1000 UV–vis Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies) and a quality profile with the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) was made.

Real time RT-PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of purified RNA using SuperScriptII (Invitrogen) and a mixture of T21 and random nonamer primers (Metabion) following the instructions for the reverse transcription reaction recommended for the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 real time cycler using human TLR9 primers (Qiagen). Human ACTB primer pair (Qiagen) was used as a positive control. The PCR products underwent agarose gel electrophoresis.

Measurement of oxidative stress by flow cytometry

SAOS-2 cells pretreated with ODNs were detached from cell culture plates. To detect ROS formation, we stained the cells for 30 min with the fluorescent reporter dye 3′-(p-hydroxyphenyl) fluorescein (HPF, Invitrogen) at a concentration of 5 μM at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS to remove excess HPF and suspended in PBS supplemented with 1 % FCS. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer and further analysed with CELL Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Significance of the represented data was calculated using unpaired Student’s t test. Data are expressed as mean ± standard errors.

Results

CpG-ODNs control survival of S. aureus inside osteoblasts

S. aureus EDCC5055 has been previously shown to successfully invade and proliferate inside SAOS-2 cells where bacteria could successfully survive inside osteoblasts during the first 6 h after infection. However, intracellular bacterial survival was dramatically reduced 20 h after infection in comparison to 4 h post-infection due to induction of apoptosis in SAOS-2 cells thus exposing the intracellular bacteria to the action of the extracellular gentamicin [4]. In this study, pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2216 or ODN2006 could clearly inhibit intracellular survival of S. aureus as the number of intracellular bacteria was significantly reduced 4 h post infection. This inhibitory effect could be also observed 20 h post infection. Pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2243 did not show any obvious reduction in intracellular survival of S. aureus either 4 h or 20 h post-infection in comparison to untreated cells (Fig. 1).

CpG-ODNs inhibit intracellular growth of S. aureus in SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cell line. SAOS-2 cells were pretreated with 250 nM of ODN2216, ODN2006, or ODN2243 4 h before infection or left untreated. Bacteria infected osteoblasts at a MOI of 30 for 30 min after which gentamicin (30 μg/ml) was added and intracellular bacterial growth was monitored at 4 h and 20 h post-infection (**P < 0, 05; *P < 0, 10)

CpG-ODNs induce TLR9 expression in SAOS-2 cells

TLR9 is normally expressed by various immune cells such as dendritic cells, B lymphocytes, monocytes and natural killer (NK) cells but could also be expressed by epithelial non-phagocytic cells such as osteoblasts [16]. Using quantitative RT-PCR for cDNAs generated from RNAs of SAOS-2 cells which were pretreated with different CpG-ODNs, we could show that expression of TLR9 in SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells was upregulated following treatment with ODN2216 and ODN2006 while pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2243 was not able to stimulate TLR9 expression as shown by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). β-Actin (ACTB) showed the same expression quantity under all conditions.

CpG-ODNs induce the expression of TLR9 in SAOS-2 cells. SAOS-2 cells were treated for 4 h with 250 nM of ODN2216 (1), ODN2006 (2), ODN2243 (3) or left untreated (4). cDNA was synthetized from isolated SAOS-2 RNA and underwent real-time quantitative PCR using human TLR9 or ACTB primers. PCR products were analyzed on 1 % agarose gel

CpG-ODNs enhance TLR9-mediated oxidative stress in SAOS-2 cells

In order to explain the mechanism of intracellular bacterial killing in SAOS-2 cells following treatment with ODN2216 and ODN2006, induction of oxidative stress inside osteoblasts was examined after treatment with different ODNs. Pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with ODN2216 or ODN2006 managed to induce ROS production inside osteoblasts as shown by flow cytometry through shift in fluorescence of HPF-stained SAOS-2 cells (Fig. 3) while pretreatment with ODN2243 as well as ODN-untreated cells did not show any enhancement of ROS production by SAOS-2 cells. Failure of ODN2243 to induce ROS production inside osteoblasts confirms the involvement of TLR9 stimulation in oxidative stress induction inside SAOS-2 cells. Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) has frequently been used to inhibit ROS production mediated by flavoenzymes, particularly NADPH oxidase [44]. Treating SAOS-2 cells with the antioxidant DPI obviously reduced S. aureus killing ability of the TLR9 agonist, CpG-ODN2216, because survival of intracellular S. aureus has significantly increased 4 h and 20 h after infection in SAOS-2 cells pretreated with both ODN2216 and DPI in comparison to treatment with ODN2216 alone indicating that intracellular S. aureus was killed throughTLR9-mediated oxidative stress (Fig. 4).

The antioxidant DPI reduces the intracellular growth inhibitory effect of ODNs on S. aureus. SAOS-2 cells were pretreated with 250 nM of ODN2216 4 h and/or with 10 μM of DPI 1 h before infection or left untreated. Bacteria infected osteoblasts as described in Fig. 1 (**P < 0, 05; *P < 0, 10)

Treatment of SAOS-2 cells with only DPI without CpG-ODN did not affect the intracellular survival of S. aureus as bacteria could grow at a level equal to that shown in untreated SAOS-2 cells.

Discussion

S. aureus infections are considered not only the most serious cause of implant, prosthetic device and intravascular line infection but also the most common cause of hospitalization for surgical drainage of pus in children or treatment of bacteremia in elderly [45–47]. Elevated levels of mortality, morbidity, and costs resulting from invasive S. aureus infections despite the introduction of several new antibiotics encouraged investigators to develop effective alternative interventional strategies to control these infections [47, 48]. Passive immunotherapy with anti S. aureus glucosaminidase monoclonal antibody has recently shown promising treatment potential in mouse model of implant-associated osteomyelitis [49].

During infection bacterial DNA is released and exposes host cells that express TLR9 to the unmethylated CpG motifs, thus stimulating a protective immune response against the invading pathogen [13, 15]. The immunostimulatory activity of bacterial DNA is mimicked by CpG-ODNs [50]. After internalization by target cells, CpG-ODNs reach the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment where they signal by interacting with TLR9 [51]. TLR9 knockout mice do not respond to stimulation by CpG-ODNs [13].

Osteoblasts have been recently shown to express TLR9 receptors that are able to transmit cellular signaling and induce osteoblasts osteoclstogenic activity [16]. S. aureus can invade and proliferate inside osteoblasts [3, 4] thus remains protected from extracellular immune responses such as antibodies, cationic peptides and recognition by phagocytic cells in addition to antibiotics. This evasion strategy plays a crucial role in recurrence and persistence of S. aureus infection. Therefore, stimulation of host innate immune responses could be an efficient approach in prophylaxis against S. aureus infection.

In this study we have shown for the first time that synthetic CpG-ODNs could significantly inhibit S. aureus intracellular survival inside SAOS-2 cells, an effect which negative CpG-ODN was not able to show. CpG-ODNs could induce expression of TLR9 in SAOS-2 cells indicating that intracellular bacterial killing effect of CpG-ODNs could be mediated by TLR9.

During the initial stages of infection by S. aureus, phagocytes including neutrophils and macrophages are recruited to the site of infection and engulf the pathogen with subsequent killing in the phagolysosome by production of lysosomal enzymes and ROS [52]. In fact, production of ROS is a common antibacterial mechanism elicited by professional antigen presenting cells in order to kill engulfed bacteria in the intracellular compartments [53]. Patients who are neutropenic or have congenital or acquired defects in polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) function are more susceptible to S. aureus infection [54]. The NADH-dependent phagocytic oxidase produces superoxide, which upon dismutation forms hydrogen peroxide. Both superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide can damage a variety of biomolecules including DNA, proteins, and lipids. Moreover, these species can destroy iron-sulfur clusters with subsequent release of iron which can undergo a Fenton reaction with hydrogen peroxide to yield hydroxyl radical which damages any biological molecule in a diffusion limited manner [55]. Anti-oxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase form part of a defense mechanism that helps S. aureus to protect itself from oxygen toxicity [44].

We have previously shown that intracellular S. aureus were surrounded by phagosomal/lysosomal membranes inside SAOS-2 cells [4], indicating that intracellular S. aureus could be exposed to the action of ROS inside osteoblasts. Our flow cytometry analysis revealed that CpG-ODNs stimulated ROS production by SAOS-2 cells. ROS were able to inhibit intracellular survival of S. aureus inside osteoblasts because pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells with the antioxidant, DPI could significantly restore the intracellular growth of S. aureus. Our study, in combination with our own previous work and the results of other groups on implant infections, shed light on a complex interplay of S. aureus at the interface of implant surface and host tissue. The pathogen, able to form a biofilm on implant surfaces, induces potentially an implant-associated infection and is capable of occasionally releasing planktonic cells thus causing bacteremia or even sepsis. Apart from its capacity to form biofilms, S. aureus is able to invade the surrounding tissue which constitutes a niche to escape the attack of the immune system and circulating antibiotics. CpG-ODNs, as shown for the first time in this study, exhibit a new weapon to prevent the nidation of S. aureus in the surrounding tissue and osteoblasts. A pre-clinical trial in goats showed promising effects of CpG-ODN against mastitis caused by E. coli infection. It induced the expression of TLR9 mRNA in mammary tissue and reduced bacterial count in milk [56].

In addition, ongoing clinical studies indicate that CpG-ODNs are safe and well-tolerated when administered as a monotherapy or as adjuvants to humans [57, 58]. In this work, it was revealed that a single administration of CPG-ODNs can induce oxidative stress through stimulation of TLR9 in epithelial non-phagocytic cells (Fig. 5) thus mounting innate immunity against invading infectious pathogens.

A schematic representation for the pretreatment of SAOS-2 cells by CpG-ODNs prior to infection with S. aureus. CpG-ODNs were internalized into the endosomal vesicles that contain TLR9. Recognition of CpG-ODNs by TLR9 upregulates the expression of TLR9 which in turn mediates formation of ROS by NADPH oxidase leading to killing the intracellular S. aureus by oxidative stress . Pretreating SAOS-2 cells with Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), a potent NADPH Oxidase inhibitor, restored the intracellular survival of S. aureus

Conclusions

In this study, CpG-ODNs could show promising effects against intracellular S. aureus. They managed to induce the expression of TLR9 in SAOS-2 cells with subsequent production of ROS leading to killing of intracellular S. aureus. Pretreatment of the infected SAOS-2 cells with DPI could restore the intracellular survival of S. aureus. Therefore, CpG-ODNs are promising new tools to support interruption of the interplay of S. aureus at the interface of implant devices and surrounding tissue.

References

Shi S, Zhang X. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus with osteoblasts (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:367–70.

Rao N, Ziran BH, Lipsky BA. Treating osteomyelitis: antibiotics and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;127:177–87.

Ellington JK, Harris M, Webb L, Smith B, Smith T, Tan K, et al. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. A mechanism for the indolence of osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2003;85:918–21.

Mohamed W, Sommer U, Sethi S, Domann E, Thormann U, Schütz I, et al. Intracellular proliferation of S. aureus in osteoblasts and effects of rifampicin and gentamicin on S. aureus intracellular proliferation and survival. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:258–68.

Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–84.

Rock FL, Hardiman G, Timans JC, Kastelein RA, Bazan JF. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:588–93.

Beutler B, Hoebe K, Du X, Ulevitch RJ. How we detect microbes and respond to them: the Toll-like receptors and their transducers. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:479–85.

Kopp E, Medzhitov R. Recognition of microbial infection by Toll-like receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:396–401.

Netea MG, van der Graaf C, Van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ. Toll-like receptors and the host defense against microbial pathogens: bringing specificity to the innate-immune system. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:749–55.

Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:131–6.

Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin signalling in the NF-kappaB pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:758–65.

Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:491–6.

Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–5.

Krug A, French AR, Barchet W, Fischer JA, Dzionek A, Pingel JT, et al. TLR9-dependent recognition of MCMV by IPC and DC generates coordinated cytokine responses that activate antiviral NK cell function. Immunity. 2004;21:107–19.

Krieg AM, Yi AK, Matson S, Waldschmidt TJ, Bishop GA, Teasdale R, Koretzky GA. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–9.

Zou W, Amcheslavsky A, Bar-Shavit Z. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides modulate the osteoclastogenic activity of osteoblasts via Toll-like receptor 9. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16732–40.

Klinman DM, Yi AK, Beaucage SL, Conover J, Krieg AM. CpG motifs present in bacteria DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2879–83.

Schwartz DA, Quinn TJ, Thorne PS, Sayeed S, Yi AK, Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA cause inflammation in the lower respiratory tract. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:68–73.

Yi AK, Chang M, Peckham DW, Krieg AM, Ashman RF. CpG oligodeoxyribonucleotides rescue mature spleen B cells from spontaneous apoptosis and promote cell cycle entry. J Immunol. 1998;160:5898–906.

Stacey KJ, Sweet MJ, Hume DA. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:2116–22.

Jakob T, Walker PS, Krieg AM, Udey MC, Vogel JC. Activation of cutaneous dendritic cells by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides: a role for dendritic cells in the augmentation of Th1 responses by immunostimulatory DNA. J Immunol. 1998;161:3042–9.

Watson JL, McKay DM. The immunophysiological impact of bacterial CpG DNA on the gut. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;364:1–11.

Lahiri A, Lahiri A, Das P, Vani J, Shaila MS, Chakravortty D. TLR 9 activation in dendritic cells enhances salmonella killing and antigen presentation via involvement of the reactive oxygen species. PLoS One. 2010;29:e13772.

McCluskie MJ, Weeratna RD. Novel adjuvant systems. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2001;1:263–71.

Ashkar AA, Rosenthal KL. Toll-like receptor 9, CpG DNA and innate immunity. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:545–56.

Klinman DM, Klaschik S, Sato T, Tross D. CpG oligonucleotides as adjuvants for vaccines targeting infectious diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:248–55.

Sun S, Zhang X, Tough DF, Sprent J. Type I interferon-mediated stimulation of T cells by CpG DNA. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2335–42.

Chu RS, Targoni OS, Krieg AM, Lehmann PV, Harding CV. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides act as adjuvants that switch on T helper (Th1) immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1623–31.

van Hunolstein C, Mariotti S, Teloni R, Alfarone G, Romagnoli G, Orefici G, et al. The adjuvant effect of synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide containing CpG motif converts the anti-Haemophilus influenzae type b glycoconjugates into efficient anti-polysaccharide and anti-carrier polyvalent vaccines. Vaccine. 2001;19:3058–66.

Kovarik J, Bozzotti P, Love-Homan L, Pihlgren M, Davis HL, Lambert PH, et al. CpG oligonucleotides can cirmcuvent the TH2 polorization of neonatal responses to vaccines but fail to fully redirect TH2 responses established by neonatal priming. J Immunol. 1999;162:1611–7.

Eastcott JW, Holmberg CJ, Dewhirst FE, Esch TR, Smith DJ, Taubman MA. Oligonucleotide containing CpG motifs enhances immune response to mucosally or systemically administered tetanus toxoid. Vaccine. 2001;19:1636–42.

Xie H, Gursel I, Ivins BE, et al. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides adsorbed onto polylactide-coglycolide microparticles improve the immunogenicity and protective activity of the licensed anthrax vaccine. Infect Immun. 2005;73(2):828–33.

Heckelsmiller K, Rall K, Beck S, Schlamp A, Seiderer J, Jahrsdorfer B, et al. Peritumoral CpG DNA elicits a coordinated response of CD8 T cells and innate effectors to cure established tumors in a murine colon carcinoma model. J Immunol. 2002;169:3892–9.

Wooldridge JE, Ballas Z, Krieg AM, Weiner GJ. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs enhance the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapy of lymphoma. Blood. 1997;89:2994–8.

Warren TL, Dahle CE, Weiner GJ. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides enhance monoclonal antibody therapy of a murine lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2000;1:57–61.

Weighardt H, Feterowski C, Veit M, Rump M, Wagner H, Holzmann B. Increased resistance against acute polymicrobial sepsis in mice challenged with immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides is related to an enhanced innate effector cell response. J Immunol. 2000;165:4537–43.

Alt V, Bitschnau A, Osterling J, Sewing A, Meyer C, Kraus R, et al. The effects of combined gentamicin-hydroxyapatite coating for cementless joint prostheses on the reduction of infection rates in a rabbit infection prophylaxis model. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4627–34.

Domann E, Wehland J, Niebuhr K, Haffner C, Leimeister-Wächter M, Chakraborty T. Detection of a Prfa-independent promoter responsible for listeriolysin gene expression in mutant Listeria monocytogenes strains lacking the PrfA regulator. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3073–5.

O’Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:91–109.

Krug A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Jahrsdörfer B, Blackwell S, Ballas ZK, et al. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2154–63.

Hasan UA, Zannetti C, Parroche P, Goutagny N, Malfroy M, Roblot G, et al. The human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein induces a transcriptional repressor complex on the Toll-like receptor 9 promoter. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1369–87.

Vollmer J, Weeratna R, Payette P, Jurk M, Schetter C, Laucht M, et al. Characterization of three CpG oligodeoxynucleotide classes with distinct immunostimulatory activities. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:251–62.

Drevets DA, Canono BP, Leenen PJ, Campbell PA. Gentamicin kills intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2222–8.

Li Y, Trush MA. Diphenyleneiodonium, an NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor, also potently inhibits mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:295–9.

Soriano A, Martinez JA, Mensa J, Marco F, Almela M, Moreno-Martínez A, et al. Pathogenic significance of methicillin resistance for patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:368–73.

Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, Schwaber MJ, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–9.

Kaye KS, Anderson DJ, Choi Y, Link K, Thacker P, Sexton DJ. The deadly toll of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in community hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1568–77.

Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–71.

Varrone JJ, Li D, Daiss JL, Schwarz EM. Anti-glucosaminidase monoclonal antibodies as a passive immunization for methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) orthopaedic infections. Bonekey Osteovision. 2011;8:187–94.

Wagner H. Bacterial CpG-DNA activates immune cells to signal “infectious danger”. Adv Immunol. 1999;73:329–368.

Ishii KJ, Takeshita F, Gursel I, Gursel M, Conover J, Nussenzweig A, et al. Potential role of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase, rather than DNA-dependent protein kinase, in CpG DNA -induced immune activation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:269–74.

Clements MO, Foster SJ. Stress resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:458–62.

Slauch JM. How does the oxidative burst of macrophages kill bacteria? Still an open question. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:580–3.

Cheung AL, Eberhardt KJ, Chung E, Yeaman MR, Sullam PM, Ramos M, et al. Diminished virulence of a sar-/agr-mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1815–22.

Anjem A, Varghese S, Imlay JA. Manganese import is a key element of the OxyR response to hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:844–58.

Zhu YM, Miao JF, Zhang YS, Li Z, Zou SX, Deng YE. CpG-ODN enhances mammary gland defense during mastitis induced by Escherichia coli infection in goats. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;15:168–76.

Davis HLCC, Morris ML, Efler SM, Cameron DW, Heathcote J. CpG ODN is safe and highly effective in humans as adjuvant to HBV vaccine: Preliminary results of Phase I trial with CpG ODN 7909. Paper presented at: The Third Annual Conference on Vaccine Research. 2000; S25: 47.

Cooper CL, Davis HL, Morris ML, Efler SM, Krieg AM, Li Y, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of CPG 7909 injection as an adjuvant to Fluarix influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2004;22:3136–43. Immunol. 1999; 73:329–368.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Olga Dakischew for technical assistance.

Funding

This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Authors’ contributions

WM, ED, VA designed and performed the experiments. ED, TC, CH, RS, WM, GM analysed the data, wrote the paper and prepared figures. TC, VA and KSL contribute materials for the experiments and reviewed drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, W., Domann, E., Chakraborty, T. et al. TLR9 mediates S. aureus killing inside osteoblasts via induction of oxidative stress. BMC Microbiol 16, 230 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0855-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0855-8