Abstract

Background

The transcription factors (TFs) in thermophilic cyanobacteria might represent a uniquely evolved gene repertoire in light of the strong selective pressure caused by hostile habitats. Understanding the molecular composition of the TF genes in thermophilic cyanobacteria will facilitate further studies regarding verifying their exact biochemical functions and genetic engineering. However, limited information is available on the TFs of thermophilic cyanobacteria. Herein, a thorough investigation and comparative analysis were performed to gain insights into the molecular composition of the TFs in 22 thermophilic cyanobacteria.

Results

The results suggested a fascinating diversity of the TFs among these thermophiles. The abundance and type of TF genes were diversified in these genomes. The identified TFs are speculated to play various roles in biological regulations. Further comparative and evolutionary genomic analyses revealed that HGT may be associated with the genomic plasticity of TF genes in Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus strains. Comparative analyses also indicated different pattern of TF composition between thermophiles and corresponding mesophilic reference cyanobacteria. Moreover, the identified unique TFs of thermophiles are putatively involved in various biological regulations, mainly as responses to ambient changes, may facilitating the thermophiles to survive in hot springs.

Conclusion

The findings herein shed light on the TFs of thermophilic cyanobacteria and fundamental knowledge for further research regarding thermophilic cyanobacteria with a broad potential for transcription regulations in responses to environmental fluctuations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thermophilic cyanobacteria are oxygen-evolving photosynthetic prokaryotes that show a ubiquitous distribution in diverse thermal environments around the world [1,2,3]. The importance of thermophilic cyanobacteria has been demonstrated in numerous studies mainly due to their contribution to a large part of geothermal ecosystems’ biomass and productivity [4]. Moreover, thermophilic cyanobacteria have been explored for various applications concerning agriculture, pharmaceutics, nutraceutical, and biofuel [5], and have been manipulated to improve the production capability of cyanofactories by various biotechnological approaches, such as metabolic engineering [6]. Nevertheless, bottlenecks are widespread in the application of cyanobacteria in biotechnology [7]. Therefore, to fully explore the industrial potential of cyanobacteria requires thorough studies on each biological block of thermophilic cyanobacteria.

Genome expression modulation is crucial for every living organism and is the underlying mechanisms of development, morphology and physiology [8]. Gene expression is one level of this modulation, in which transcription factors (TFs) are one of the key players [9]. TFs usually are structurally composed of a DNA binding domain (DBD), an oligomerization domain responsible for interaction with other TFs, and a transcription regulation domain controlling gene expression [10]. The sequences of most TFs possess only one type of DBD in one or multiple copies, while several DBD types are also present in some TFs [11]. The TF proteins affect the expression of multiple target genes by binding to specific DNA motifs in their promoter regions.

As the increasing number of prokaryotes with complete genome sequences, in silico studies have been extensively performed to identify putative TFs in prokaryotic genomes [10, 12]. More importantly, taxonomically diverse data facilitate comparative analyses between different species or lineages, further providing insights into taxonomic characteristics of the TF complement of different organisms. In the past decade, many cyanobacterial genomes from thermal environments have been elucidated [13, 14]. However, the TF genes in thermophilic cyanobacteria are rarely characterized.

The utilization of TFs has been widely applied in the construction of synthetic genetic networks for cyanobacteria [7, 15]. Cyanobacterial strains with engineered transcription machinery might provide solutions for construction of highly efficient production platforms for biotechnical applications in the future. Furthermore, thermophilic cyanobacteria might evolve into a unique repertoire of TF genes in light of the strong selective pressure caused by hostile habitats. Understanding the molecular composition of the TF genes in thermophilic cyanobacteria will be helpful as a prerequisite for verifying their exact biochemical functions and for further genetic engineering.

Herein, we carried out genome-wide identification and comparison of the TF repertoire of thermophilic cyanobacteria. The TF composition were thoroughly analyzed and compared. Special focus was given to the genus and strain-specific TFs between these thermophilic cyanobacteria and corresponding mesophilic cyanobacterium, and their putative functions was discussed.

Materials and methods

Source dataset of thermophilic cyanobacteria

A total of 22 thermophilic cyanobacteria were compiled into the genome dataset. These thermophilic cyanobacteria were previously verified by the literatures [16,17,18]. Briefly, the 22 thermophiles were taxonomically assigned to six families, including Leptolyngbyaceae: Leptodesmis sichuanensis A121 [19] and Leptothermofonsia sichuanensis E412 [20]; Oculatellaceae: Leptolyngbya sp. JSC-1 [21], Thermocoleostomius sinensis A174 [22], Thermoleptolyngbya sp. O-77 [23] and T. sichuanensis A183 [24]; Gloeomargaritaceae: Synechococcus sp. C9 [25]; Thermostichaceae: Thermostichus sp. 60AY4M2, 63AY4M2, 65AY6A5, 65AY6Li [26], JA-2-3B and JA-3-3Ab [27]; Thermosynechococcaceae: Thermosynechococcus lividus PCC 6715 [18], T. nakabusensis NK55 [28], T. sichuanensis E542 [6], T. taiwanensis CL-1 [29] and TA-1 [30], T. vestitus BP-1 [31], Thermosynechococcus sp. M46_R2017_013 and M98_K2018_005 (hereafter M46 and M98) [32]; and Trichocoleusaceae: Trichothermofontia sichuanensis B231 [33]. The genome, protein sequences, and genomic annotations of the thermophilic cyanobacteria collected were retrieved from the genomic resources of the NCBI. The genomes with no or incomplete annotations were annotated using the RAST annotation system [34], which were summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Identification and classification of TFs

The TF genes were identified in each genome using P2RP (http://www.p2rp.org/, accessed on 20 May 2023) [35]. All the TF genes detected were categorized into families by P2RP based on domain architecture, according to the scheme implemented in the P2CS and P2TF databases [36, 37]. The Pearson coefficient was employed to assess the correlation between the TF gene number and genome size by using the cor.test function in R v3.6.2. Significance levels of 0.05 and 0.01 were applied for the analysis.

Identification of orthologous proteins

According to the bidirectional best hit (BBH) criterion, orthologous proteins of TF genes were identified in focal taxa using BLASTP. The BLASTP alignments were performed with the following thresholds: identity percentage greater than 40% and query coverage greater than 75% [38].

Phylogeny

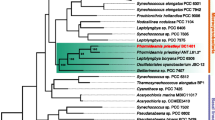

The 16 S rRNA gene sequences were collected for the thermophile collective by retrieval from the NCBI or their extraction from genome sequences. We also included the 16 S rRNA sequences of cyanobacterial references selected according to the phylogenetic relationships based on the literature [39] and the Cyanobacterial Phylogeny and Taxonomy Reference Website. Alignments of 16 S rRNA gene sequences were generated using MAFFT v7.453 [40]. Phylogram of 16 S rRNA gene sequences was inferred using Neighbor-Joining method implemented in MEGA 11.

The similarity clustering was illustrated using an Unweighted Pair Group Method with Algorithmic Mean (UPGMA) based on the AAI (Average Amino acid Identity) matrix estimating all-against-all distances in a collection of focal genomes [41] and visualized using Mega11. Moreover, the 0/1 binary matrix representing the presence or absence of the TF families was used to calculate similarity using Dice’s coefficient [42] for resolving relationships among the thermophiles, and clustering analysis was further performed using UPGMA implemented in NTSYS-pc v.2.10e [43].

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic inference of thermophilic cyanobacteria

To better understand the phylogenetic position of the surveyed thermophilic cyanobacteria, 16 S rRNA sequences were employed for phylogenetic inference. The complete phylogram refers to Supplementary Fig. 1. As indicated by Fig. 1, all the thermophilic cyanobacteria were taxonomically assigned to the corresponding genus and family, except for Leptolyngbya sp. JSC-1 and Synechococcus sp. C9. Leptolyngbya sp. JSC-1 appeared to be a novel genus of family Oculatellaceae, rather than a member of genus Leptolyngbya sensu stricto within family Leptolyngbyaceae. Synechococcus sp. C9 showed an identity of 87.5% to PCC 7942, the type strain of genus Synechococcus. Instead, a high similarity (98.2%) was observed between C9 and Gloeomargarita lithophora Alchichica-D10 from family Gloeomargaritaceae, suggesting that C9 was not a member of family Synechococcaceae. Both assignments of the two strains are consistent with previous studies that the actual taxonomy of Leptolyngbya JSC-1 and Synechococcus C9 has not been validated yet [44, 45]. In addition, Thermosynechococcus sp. M98 was excluded from phylogenetic analysis due to extremely short sequence of 16 S rRNA. However, whole genome average nucleotide identity (ANI) was calculated for genus and species delineation of this strain. The ANI values between M98 and the other seven Thermosynechococcus strains ranged from 83.1 to 92.3%, indicating its allocation as a different species within genus Thermosynechococcus according to the suggested values for genus (ANI > 83%) and species (ANI < 96%) delimitation [46].

Phylogenetic inference of 16 S rRNA gene sequences representing 128 cyanobacterial strains. Collapsed genera are indicated by black polygons, with a length corresponding to the distance from the most basal sequence to the most diverged sequence of the genus. The thermophilic cyanobacteria are in bold

TF composition in thermophilic cyanobacteria

The predicted TFs from the genomes of 22 thermophilic cyanobacteria were identified and classified, the overall features and detailed results of which were summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively. A total of 1,623 TFs were identified in the genomes of these thermophiles. The TFs were classified into four groups based on the P2TF scheme [37], namely transcriptional regulator (TR), one-component system (OCS), response regulator (RR) and sigma factor (SF). TR is the most abundant category of TFs among all the 22 genomes, followed by RR (Table 1). A distinct number of TF genes are exhibited among these genomes (Table 1), tremendously varying from 39 (Thermosynechococcus M46) to 210 (Leptolyngbya JSC-1). Although the intergenus variation of TF number is evident, different intragenus variations are observed (Table 1). Thermoleptolyngbya and Thermostichus genomes show a conserved pattern of TF number within the genus, whereas more variation is present among Thermosynechococcus genomes. Intriguingly, the number of TF genes appeared to be positively correlated with genome size (Table 1). Thus, we further compiled a genome dataset of 69 cyanobacterial genomes on a larger scale (Supplementary Table 3) to verify the correlation between genome size and TF number. The cyanobacterial genome dataset represented a diverse array of ecological niches, including alkaline, freshwater, marine, terrestrial and thermal niches. The Pearson analysis indicates that the number of TFs is positively associated with genome size (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2).

In addition, the proportion of putative TFs in the predicted proteomes ranges from 1.75 to 3.04% (Table 1). Such percentage is in accordance with previous studies regarding prokaryotic organisms, such as S. elongatus PCC 7942 (2.7%) [37], but is lower than that of eukaryotic organisms, e.g. unicellular organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae (3.5%) [47], multicellular organism Arabidopsis thaliana (5.9%) [48]. Moreover, the average proportion in filamentous thermophiles is 2.62%, higher than that (2.27%) in unicellular thermophiles. Previous studies reported that the proportions of TFs in organisms are correlated with the complexity of organisms in light of the fact that TFs play a role in the morphology diversification of organisms [49, 50]. This may explain the higher proportion of TFs in filamentous thermophiles than in unicellular thermophiles. Besides, the subsequent analysis suggests the presence of the TF family unique to specific lineages or species. Thus, it is speculated that the emergence of TF families’ expansion may coincide with the divergence of cyanobacterial lineages [51].

Comparison of TF families among thermophilic cyanobacteria

TF proteins were sub-categorized into families based on domain organization. A total of 40 TF families as well as unclassified TF families are present in the genomes of the 22 thermophilic cyanobacteria (Fig. 3), including 34 families as TR and OCS, 3 families as RR, and 3 families as SF. Intergenus variations are evident in TF family numbers, while there are extremely limited intragenus variations. The highest TF family number is observed in Leptolyngbya JSC-1 (32), followed by Thermoleptolyngbya O-77 (31), and Leptothermofonsia E412 (30). Overall, filamentous thermophiles show a higher TF family number (28 on average) than unicellular thermophiles (21 on average).

As indicated by Fig. 3 illustrated using TBtools [52], the type of TF family is diverse among the genomes. Eleven TF families are common to all the thermophiles, including ArsR, Crp, Fur, LysR, Rrf2, SfsA, Xre, NarL, OmpR, Ecf, and RpoE family. These TF families account for more than 50% of the TF families in each genome, ranging from 53.81% (Leptolyngbya JSC-1) to 81.48% (Thermosynechococcus CL-1). The results suggest a conserved pattern of TF families among the surveyed thermophilic cyanobacteria. Particularly, within the genus, the percentages of common TF families are higher than 91.46% and 91.25% in Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus genomes, respectively. Such a high proportion in the two genera indicates an extremely conserved genomic core regarding TF families, which is in line with the previous core-genome study of Thermosynechococcus genomes [53].

Eight TF families are lineage-specific, namely KorB in Leptolyngbya JSC-1, RpiR in Leptothermofonsia, LacI in Thermocoleostomius, AsnC, FaeA, FlhD and RpoN in Thermoleptolyngbya, and DtxR in Synechococcus. The AraC family was only found specifically in the surveyed filamentous thermophilic cyanobacteria. Several TF families are absent only in one or two specific lineages, including CsoR and NrdR in Synechococcus, LuxR and PadR in Thermostichus, and LexA, MarR and TetR in Synechococcus and Thermosynechococcus.

The lineage-specific TF families may reveal the evolutionary history of these thermophiles. Therefore, cluster analysis was performed using a binary matrix representing the presence or absence of the TF families to infer the relationships among the thermophiles. As shown in Fig. 3, each lineage is well separated from the other due to the presence of TF families specific to the lineage. The clustering of thermophiles is consistent with genus-level taxonomic assignment of these lineages in the phylogram of 16 S rRNA (Fig. 1). At the family level, discrepancy is noticed. JSC-1 from family Oculatellaceae appeared to be closer to the two genera from family Leptolyngbyaceae, while A174 was located in a separate branch, rather than with other genera from family Oculatellaceae. The incompatible topologies indicate that the evolution of TF families is partially inconsistent with phylogenetic relationship of these thermophiles. In addition, sub-clusters are also noticed within genus Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus, suggesting the divergence of TF families in the two genera during their evolutionary process.

Putative functions of common and specific TF families among thermophilic cyanobacteria

The 11 common TF families among thermophilic cyanobacteria showed diverse putative functions and may regulate the transcription of key genes involved in the acclimation responses to environmental changes. The two common response regulators, OmpR and NarL family, constituted the overwhelming majority of the putative RRs identified in each genome. The OmpR family may function as a key regulator to mediate a wide range of biological functions related to osmolarity, phosphate assimilation, antibiotic resistance, virulence and toxicity [54], whereas the NarL family was documented to control the expression of genes related to nitrogen fixation, sugar phosphate transport, nitrate and nitrite metabolism, quorum sensing, and osmotic stress [55]. Similarly, the vast majority of the putative sigma factors identified in each genome were classified into the following two families: Ecf and RpoE family, both of which exhibit the extracytoplasmic function. The RpoE family can trigger the expression of genes protecting against photooxidative stress, and may partially overlap with the heat-shock response [56]. The Ecf family may be involved in DNA repair response, cell wall stress, and amino acid starvation [57, 58].

The remaining seven common TF families were grouped into one-component systems and transcriptional regulators. The Xre family may play important roles in pathogenicity and virulence mechanisms, e.g. biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and homeostasis [59, 60]. The Crp family adjusts global gene expression in response to the C-to-N balance in the cells, and the LysR family extensively facilitates the acclimation of cells to oxygenic phototrophy [61]. The metalloregulator ArsR family is involved in stress response to metal ions in cyanobacteria [62]. Another metal regulon, the Fur family, controls genes for iron/zinc acquisition or genes involved in oxidative stress [63]. Members of the Rrf2 family regulate gene expression to enable adaptation, maintenance of homeostasis and cell protection [64]. Moreover, all the genomes of thermophilic cyanobacteria contain a SfsA TF that is known to be involved in sugar fermentation [65].

In addition to the common TF families, lineage-specific TF families might be more important for themselves to perform unique regulation of gene expressions. The KorB family unique in Leptolyngbya may control the replication [66]. The RpiR may be a transcription activator responsible for sugar catabolism in Leptothermofonsia [67]. The LacI family in Thermocoleostomius may sense sugar effectors and regulate carbohydrate utilization genes [68]. The TF families unique in Thermoleptolyngbya may be involved in various biological processes, e.g. amino acid metabolism and transport by the AsnC family [69], DNA methylation by the FaeA family [70], and nitrogen and carbon metabolism by RpoN family [71]. Although the FlhD was identified in Thermoleptolyngbya, FlhC was absent from the genome. Given the fact that the flhDC operon is essential for the transcription of all the genes in the flagellar cascade [72], it is unclear that the FlhD in Thermoleptolyngbya act as a global regulator involved in cellular processes or not. Synechococcus possessed a unique metalloregulator, the DtxR family, which may regulate the expression of genes involved in metal homeostasis in the cell, particularly genes for manganese uptake transporters [73]. The AraC family may participate in the control of genes involved in important biological processes such as carbon source utilization, morphological differentiation, secondary metabolism, pathogenesis and stress responses [74].

The CsoR family is widely distributed and regulates the regulons involved in detoxification in response to extreme copper stress [75]. The absence of CsoR in Synechococcus C9 suggests that an alternative mechanism may be utilized for copper resistance. In addition, Synechococcus C9 excluded another widely conserved regulator, NrdR, of Ribonucleotide reductase genes [76]. LuxR and PadR are widespread and functional diverse transcription factors [77, 78], which are missing in Thermostichus. The LexA, MarR and TetR are absent in Synechococcus and Thermosynechococcus genomes. LexA regulates gene expression in response to environmental changes (e.g. salt stress) [79], MarR is critical for bacterial cells to respond to chemical signals and to convert such signals into changes in gene activity [80], and TetR regulates various essential processes (e.g. metabolism, biofilm formation and efflux gene expression) [81]. The missing conserved TF families might have no lethal impact on these thermophiles to survive in hostile thermal niches. Conversely, the corresponding functions of regulation may be compensated by other TFs, since most TFs are global multi-target regulators. Moreover, the presence or absence of conserved TF families among these thermophilic cyanobacteria could be explained either by the loss of these families during evolutionary history or by the acquisition of these families by horizontal gene transfer.

Orthologous TFs in thermostichus and thermosynechococcus

Only Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus strains were included for the identification of orthologous TF proteins, since the other genera studied have only one or two strains sequenced for whole genomes. The orthologous TF proteins shared by the Thermostichus or Thermosynechococcus strains were summarized in Supplementary Table 4. As for the six Thermostichus genomes, 300 (91.5%) out of 328 putative TF genes were common to all the genomes, suggesting a quite conserved core set of TF genes in these Thermostichus strains. Regarding the eight Thermosynechococcus genomes, 256 (67.9%) out of 377 putative TCS genes were common to all the genomes (Supplementary Table 4). Compared to the core set in Thermostichus strains, relatively less conserved TF genes was shown by the Thermosynechococcus genomes.

Accessory TFs in thermostichus and thermosynechococcus

Apart from the core set of TF genes, accessory TF genes might be biologically more important due to their contribution to the genome plasticity. In these Thermostichus genomes, 28 TF genes were identified as accessory (Supplementary Table 4). Among them, six were strain-specific TFs, four of which were affiliated with JA-2-3Ba (Fig. 4a). A total of 121 TF genes were found to be accessory in these Thermosynechococcus genomes (Supplementary Table 4). Only 12 TF genes were strain-specific (Fig. 4b), contributed by PCC 6715 (four genes), E542 (three genes), M46 (two genes), and NK55, BP-1 and M98 (one gene each).

Occurrence of accessory TF genes in Thermostichus (a) and Thermosynechococcus strains (b). The UPGMA trees on the left were built based on AAI distances of focal genomes. The TFs were named by the strain name plus accession number and only one ortholog was shown. The full dataset was summarized in Supplementary Table 4

In addition, comparative and evolutionary genomic analyses were conducted to infer the origin of accessory TF in Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus strains. Among the 28 accessory TF genes in the Thermostichus genomes, three gene loss events and three gene acquisition events were putatively identified, while five gene gain/loss events may occur during the evolutionary process (Fig. 4a). The gene loss events occurred either recently in a single Thermostichus strain or a common ancestor of Thermostichus strains, both indicating the possible recent loss events. Among the three gene acquisition events, two TFs (JA-3-3Ab_ABD00413 and 65AY6A5_PIK88468) may be independently acquired by the two strains; and the three TFs (65AY6A5_PIK84631, 63AY4M2_PIK86529 and 60AY4M2_PIK95596) may be acquired by the common ancestor of the three strains.

Regarding the 121 accessory TF genes in the Thermosynechococcus genomes, 12 gene loss events and 21 acquisition events were putatively identified, whereas four gene gain/loss events were observed (Fig. 4b). Numerous gene loss events and acquisition events were associated with PCC 6715, which might contribute to the divergence indicated by the phylogeny of this species among the Thermosynechococcus strains (Fig. 4b). The gene loss events were complex among the Thermosynechococcus strains, which occurred recently in a single strain, a common ancestor of strains, or independently in two or three strains. Similarly, acquisition events were also complicated, which happened only in a single strain, in several strains, in a clade, and in a common ancestor.

Conclusively, HGT events may be involved in the evolutionary history of TF genes in Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus strains. The results regarding Thermosynechococcus strains were in accordance with previous reports that numerous putative genes horizontally transferred from other bacteria have been actively acquired by Thermosynechococcus species, conferring the acclimation of them to stressful niches in hot springs [29, 82]. However, fewer HGT events were found in Thermostichus strains, which were inhabited in niches that were near 73oC [83]. This could be explained by a tentative hypothesis that extremely hot spring environments may provide more limited opportunity for lateral gene transfer, which in turn could lead to less opportunity for lateral gene transfer [53]. Taken together, the results indicated genome plasticity of TF genes may be used for coping with unique challenges that strains of the two genera faced in hostile habitats.

Comparative analysis of TFs between thermophilic and mesophilic cyanobacteria

We further compared the TFs between the surveyed thermophilic cyanobacteria and mesophilic cyanobacteria. According to the family-level allocation in the 16 S rRNA phylogram (Supplementary Fig. 1), one reference genome of mesophilic cyanobacteria was selected from each family based on the genome quality, ecological niches and/or temperature characteristics. The TFs of each genus were compared to the TFs of corresponding reference genome. Synechococcus PCC 7942 was used as the reference since there’s no other genus within family Thermosynechococcaceae and Thermostichaceae. The identified genus-specific and strain-specific TFs were further compared to TFs of Synechocystis PCC 6803 for function prediction.

Within family Oculatellaceae, Elainella E1 was selected as reference, which was isolated from ephemeral waterbody (26.7oC, pH 6.06) in the forest, Cat Tien National Park, Vietnam [84]. Numerous TFs of the two Thermoleptolyngbya strains, Thermocoleostomius A174, and Leptolyngbya JSC-1 were identified to be unique to the TFs of Elainella E1, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). The identified unique TFs belong to diverse types (Supplementary Table 4), among which AraC family appears to be more abundant in these thermophiles. Several AraC TFs are orthologous to the TFs (sll1205, sll1408 and sll1489) of Synechocystis PCC 6803 (Supplementary Table 5), which may function as iron stress regulon in these thermophiles [85]. In addition, Thermoleptolyngbya O-77 has a homolog of sll0184 that is involved in the acclimation to low inorganic carbon during the prolonged high temperature [86], while Leptolyngbya JSC-1 possesses a homolog of sll1594, a repressor of the genes encoding components of Ci transporters, such as the NDH complex and the high-affinity sodium/bicarbonate symporter SbtA, under high carbon conditions [87]. Both TFs may confer the thermophilic cyanobacteria with more alternative strategies to survive in environments with significant CO2 fluctuation, particularly in hot springs [18]. Moreover, many TFs from these thermophiles are also identified to be homologs of the TFs in Synechocystis PCC 6803 that are involved in regulation in responses to environmental changes, such as nitrogen, nitrate, metal and phosphate (Supplementary Table 5).

Around 38% of the TFs in Leptodesmis A121 and Leptothermofonsia E412 (Supplementary Table 4) are separately unique to the TFs of Leptolyngbya dg5, a freshwater cyanobacterium. Two unique TFs of the two thermophiles are annotated as regulon to metals (Supplementary Table 5). Unfortunately, no putative functions were predicted for the other unique TFs.

Trichothermofontia B231 was compared to Trichocoleus FACHB-46, a terrestrial cyanobacterium [13]. Around 70% of the TFs in Trichothermofontia B231 are orthologous to that of FACHB-46 (Supplementary Table 4), may suggesting a similar TF composition.

Compared to Synechococcus PCC 7942, homologs are found to account for around 70% of the TFs in each Thermosynechococcus genome (Supplementary Table 4). Four Thermosynechococcus-specific TFs are homologs of sll0176, sll1371, slr1783 and slr1909 (Supplementary Table 5), may participating metal responses, twitching motility, acid tolerance and other transcription regulation [88,89,90,91]. The strain-specific TF (PCC6715.100) from PCC 6715 (Supplementary Table 5) may be involved in cadmium tolerance and metal homeostasis [92].

Within family Gloeomargaritaceae, G. lithophora is to date the only described genus, Alchichica-D10 as the type strain [93].The mesophilic strain grew within a temperature range of 15–30 °C, whereas thermophilic C9 can grow at up to 55 °C [25]. A total of 38 orthologous TFs are shared by the two strains and the 11 TFs unique to C9 are all TR, representing seven TF types (Supplementary Table 4). Among them, the TF (C9.469), a homolog of sll5035, may be involved in arsenic resistance of C9 and obtained via horizontal gene transfer [94]. In addition, the TF (C9.1780) is homologous to sll7009, a negative regulator specific for the CRISPR1 subtype I-D system in Synechocystis PCC 6803 [95]. And this TF has no homologs or shares similar functions of other TFs in the other surveyed thermophiles. This result indicates that some regulations are limitedly shared by thermophilic and mesophilic cyanobacteria. More importantly, a comprehensive genomic comparison is essential in future to elucidate the thermal difference between the two strains.

Unlike Thermosynechococcus, approximately half of TFs in each Thermostichus genome are orthologous to that of Synechococcus PCC 7942 (Supplementary Table 4). The Thermostichus-specific TFs are homologs of sll1371 and slr1909 (Supplementary Table 5), may functioning for twitching motility and acid tolerance [89, 91]. The strain-specific TF (JA-2-3Ba_ABD02443.1), a homolog of sll1689, may facilitate this strain to cope with nitrogen starvation [96].

Overall, the comparisons suggest a different TF composition between the surveyed thermophiles and corresponding mesophiles. Furthermore, the identified TFs of thermophiles that are distinct from that of mesophiles are putatively involved in various biological regulations, mainly as responses to ambient changes. Those potential regulatory systems may benefit the thermophiles to survive in hot springs, and may represent the characteristic molecular signatures in these thermophiles and should be therefore experimentally elucidated in the near future.

Conclusions

Herein, a thorough investigation and comparative analysis was carried out regarding the composition and abundance of TFs in 22 thermophilic cyanobacteria. The results suggested a fascinating diversity of the TFs among these thermophiles. The abundance and type of TF genes were diversified in these genomes. The identified TFs are speculated to play various roles in biological regulations. Further comparative and evolutionary genomic analyses revealed that HGT may be associated with the genomic plasticity of TF genes in Thermostichus and Thermosynechococcus strains. Comparative analyses also indicated different pattern of TF composition between thermophiles and corresponding mesophilic reference cyanobacteria. Moreover, the identified unique TFs of thermophiles are putatively involved in various biological regulations, mainly as responses to ambient changes, may facilitating the thermophiles to survive in hot springs. Conclusively, the obtained findings provided insights into the TFs of thermophilic cyanobacteria and fundamental knowledge for further research regarding thermophilic cyanobacteria with a broad potential for transcription regulations in response to environmental fluctuations.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are openly available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/).

References

Tang J, Liang Y, Jiang D, Li L, Luo Y, Shah MMR, Daroch M. Temperature-controlled thermophilic bacterial communities in Hot Springs of western Sichuan, China. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):134.

Mehetre GT, Zothanpuia, Deka P, Carrie W, Lalrokimi, Singh BP. Chap. 6 - Thermophilic and thermotolerant cyanobacteria: Environmental and biotechnological perspectives. In: Cyanobacterial lifestyle and its applications in biotechnology Edited by Singh P, Fillat M, Kumar A: Academic Press; 2022: 159–178.

Tang J, Jiang D, Luo Y, Liang Y, Li L, Shah M, Da Roch M. Potential new genera of cyanobacterial strains isolated from thermal springs of western Sichuan, China. Algal Res. 2018;31:14–20.

Esteves-Ferreira AA, Inaba M, Fort A, Araújo WL, Sulpice R. Nitrogen metabolism in cyanobacteria: metabolic and molecular control, growth consequences and biotechnological applications. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2018;44(5):541–60.

Patel A, Matsakas L, Rova U, Christakopoulos P. A perspective on biotechnological applications of thermophilic microalgae and cyanobacteria. Bioresour Technol. 2019;278:424–34.

Liang Y, Tang J, Luo Y, Kaczmarek MB, Li X, Daroch M. Thermosynechococcus as a thermophilic photosynthetic microbial cell factory for CO2 utilisation. Bioresour Technol. 2019;278:255–65.

Stensjö K, Vavitsas K, Tyystjärvi T. Harnessing transcription for bioproduction in cyanobacteria. Physiol Plant. 2018;162(2):148–55.

Wisniewska A, Wons E, Potrykus K, Hinrichs R, Gucwa K, Graumann P, Mruk I. Molecular basis for lethal cross-talk between two unrelated bacterial transcription factors - the regulatory protein of a restriction-modification system and the repressor of a defective prophage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(19):10964–80.

Spitz F, Furlong EEM. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(9):613–26.

Thiriet-Rupert S, Carrier G, Chénais B, Trottier C, Bougaran G, Cadoret JP, Schoefs B, Saint-Jean B. Transcription factors in microalgae: genome-wide prediction and comparative analysis. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:282.

Wilson D, Charoensawan V, Kummerfeld SK, Teichmann SA. DBD––taxonomically broad transcription factor predictions: new content and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;36(suppl1):D88–D92.

Rayko E, Maumus F, Maheswari U, Jabbari K, Bowler C. Transcription factor families inferred from genome sequences of photosynthetic stramenopiles. New Phytol. 2010;188(1):52–66.

Chen M-Y, Teng W-K, Zhao L, Hu C-X, Zhou Y-K, Han B-P, Song L-R, Shu W-S. Comparative genomics reveals insights into cyanobacterial evolution and habitat adaptation. Isme J. 2021;15(1):211–27.

Alcorta J, Alarcón-Schumacher T, Salgado O, Díez B. Taxonomic novelty and distinctive genomic features of hot spring cyanobacteria. Front Genet. 2020;11:568223.

Koskinen S, Hakkila K, Kurkela J, Tyystjärvi E, Tyystjärvi T. Inactivation of group 2 σ factors upregulates production of transcription and translation machineries in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10305.

Tang J, Zhou H, Yao D, Du L, Daroch M. Characterization of molecular diversity and organization of phycobilisomes in thermophilic cyanobacteria. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5632.

Tang J, Yao D, Zhou H, Wang M, Daroch M. Distinct molecular patterns of two-component signal transduction systems in thermophilic cyanobacteria as revealed by genomic identification. Biology. 2023;12(2):271.

Tang J, Zhou H, Yao D, Riaz S, You D, Klepacz-Smółka A, Daroch M. Comparative genomic analysis revealed distinct molecular components and organization of CO2-concentrating mechanism in thermophilic cyanobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2022;12:876272.

Tang J, Du L, Li M, Yao D, Waleron M, Waleron KF, Daroch M. Characterization of a novel hot-spring cyanobacterium Leptodesmis sichuanensis sp. nov. and genomic insights of molecular adaptations into its habitat. Front Microbiol. 2022;12:739625.

Tang J, Shah MR, Yao D, Du L, Zhao K, Li L, Li M, Waleron M, Waleron M, Waleron KF, et al. Polyphasic identification and genomic insights of Leptothermofonsia sichuanensis gen. sp. nov., a novel thermophilic cyanobacteria within Leptolyngbyaceae. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:765105.

Brown II, Bryant DA, Casamatta D, Thomas-Keprta KL, Sarkisova SA, Shen G, Graham JE, Boyd ES, Peters JW, Garrison DH. Polyphasic characterization of a thermotolerant siderophilic filamentous cyanobacterium that produces intracellular iron deposits. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(19):6664–72.

Jiang Y, Tang J, Liu X, Daroch M. Polyphasic characterization of a novel hot-spring cyanobacterium Thermocoleostomius sinensis gen et sp. nov. and genomic insights into its carbon concentration mechanism. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1176500.

Yoon KS, Nguyen NT, Tran KT, Tsuji K, Ogo S. Nitrogen fixation genes and nitrogenase activity of the non-heterocystous cyanobacterium Thermoleptolyngbya sp. O-77. Microbes Environ. 2017;32(4):324–9.

Tang J, Li L, Li M, Du L, Shah MR, Waleron M, Waleron M, Waleron KF, Daroch M. Description, taxonomy, and comparative genomics of a novel species, Thermoleptolyngbya sichuanensis sp. nov., isolated from Hot Springs of Ganzi, Sichuan, China. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:696102.

Kono M, Martinez JN, Sato T, Haruta S. Draft genome sequence of the thermophilic unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain C9. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022;11(8):e00294–00222.

Olsen MT, Nowack S, Wood JM, Becraft ED, LaButti K, Lipzen A, Martin J, Schackwitz WS, Rusch DB, Cohan FM, et al. The molecular dimension of microbial species: 3. Comparative genomics of Synechococcus strains with different light responses and in situ diel transcription patterns of associated putative ecotypes in the Mushroom Spring microbial mat. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:604–4.

Bhaya D, Grossman AR, Steunou A-S, Khuri N, Cohan FM, Hamamura N, Melendrez MC, Bateson MM, Ward DM, Heidelberg JF. Population level functional diversity in a microbial community revealed by comparative genomic and metagenomic analyses. Isme J. 2007;1(8):703–13.

Stolyar S, Liu Z, Thiel V, Tomsho LP, Pinel N, Nelson WC, Lindemann SR, Romine MF, Haruta S, Schuster SC, et al. Genome sequence of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus sp. strain NK55a. Genome Announc. 2014;2(1):e01060–01013.

Cheng Y-I, Chou L, Chiu Y-F, Hsueh H-T, Kuo C-H, Chu H-A. Comparative genomic analysis of a novel strain of Taiwan hot-spring cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus sp. CL-1. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:82.

Leu J-Y, Lin T-H, Selvamani MJP, Chen H-C, Liang J-Z, Pan K-M. Characterization of a novel thermophilic cyanobacterial strain from Taian Hot Springs in Taiwan for high CO2 mitigation and C-phycocyanin extraction. Process Biochem. 2013;48(1):41–8.

Nakamura Y, Kaneko T, Sato S, Ikeuchi M, Katoh H, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Iriguchi M, Kawashima K, Kimura T, et al. Complete genome structure of the thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus Elongatus BP-1. DNA Res. 2002;9(4):123–30.

Saxena R, Dhakan DB, Mittal P, Waiker P, Chowdhury A, Ghatak A, Sharma VK. Metagenomic analysis of Hot Springs in central India reveals hydrocarbon degrading thermophiles and pathways essential for survival in extreme environments. Front Microbiol. 2017;7:2123.

Tang J, Zhen Z, Jiang Y, Yao D, Waleron KF, Du L, Daroch M. Characterization of a novel thermophilic cyanobacterium within Trichocoleusaceae, Trichothermofontia sichuanensis gen. et sp. nov., and its CO2-concentrating mechanism. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1111809.

Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):75.

Barakat M, Ortet P, Whitworth DE. P2RP: a web-based framework for the identification and analysis of regulatory proteins in prokaryotic genomes. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:269.

Ortet P, Whitworth DE, Santaella C, Achouak W, Barakat M. P2CS: updates of the prokaryotic two-component systems database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D536–541.

Ortet P, De Luca G, Whitworth DE, Barakat M. P2TF: a comprehensive resource for analysis of prokaryotic transcription factors. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:628.

Tang J, Du L, Liang Y, Daroch M. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of Synechococcus sp. CS-601 (SynAce01), a cold-adapted cyanobacterium from an oligotrophic Antarctic habitat. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(1):152.

Komárek J, Johansen J, Smarda J, Strunecký O. Phylogeny and taxonomy of Synechococcus-like cyanobacteria. Fottea. 2020;20:171–91.

Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80.

Rodriguez -RLM, Konstantinidis KT. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1900v1901.

Dice LR. Measures of the Amount of Ecologic Association between Species. Ecology. 1945;26(3):297–302.

Rohlf FJ. NTSYS-pc - Numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system. New York: Exeter Publishing Setauke; 2000.

Yao D, Cheng L, Du L, Li M, Daroch M, Tang J. Genome-wide investigation and analysis of microsatellites and compound microsatellites in Leptolyngbya-like species. Cyanobacteria Life. 2021;11(11):1258.

Tang J, Yao D, Zhou H, Du L, Daroch M. Reevaluation of parasynechococcus-like strains and genomic analysis of their microsatellites and compound microsatellites. Plants. 2022;11(8):1060.

Jain C, Rodriguez RL. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5114.

Messina DN, Glasscock J, Gish W, Lovett M. An ORFeome-based analysis of human transcription factor genes and the construction of a microarray to interrogate their expression. Genome Res. 2004;14(10b):2041–7.

Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang C, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–10.

Nitta KR, Jolma A, Yin Y, Morgunova E, Kivioja T, Akhtar J, Hens K, Toivonen J, Deplancke B, Furlong EE, et al. Conservation of transcription factor binding specificities across 600 million years of bilateria evolution. eLife. 2015;4:e04837.

Vogel C, Chothia C. Protein family expansions and biological complexity. PLoS Comp Biol. 2006;2(5):e48.

Lang D, Weiche B, Timmerhaus G, Richardt S, Riaño-Pachón DM, Corrêa LG, Reski R, Mueller-Roeber B, Rensing SA. Genome-wide phylogenetic comparative analysis of plant transcriptional regulation: a timeline of loss, gain, expansion, and correlation with complexity. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:488–503.

Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R. TBtools: an integrative Toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big Biological Data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202.

Prondzinsky P, Berkemer SJ, Ward LM, McGlynn SE. The Thermosynechococcus genus: wide environmental distribution, but a highly conserved genomic core. Microbes Environ. 2021;36(2):ME20138.

Chakraborty S, Winardhi RS, Morgan LK, Yan J, Kenney LJ. Non-canonical activation of OmpR drives acid and osmotic stress responses in single bacterial cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1587.

Rodríguez-Moya J, Argandoña M, Reina-Bueno M, Nieto JJ, Iglesias-Guerra F, Jebbar M, Vargas C. Involvement of EupR, a response regulator of the NarL/FixJ family, in the control of the uptake of the compatible solutes ectoines by the halophilic bacterium Chromohalobacter salexigens. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:256.

Glaeser J, Nuss AM, Berghoff BA, Klug G. Singlet oxygen stress in microorganisms. Adv Microb Physiol. 2011;58:141–73.

Miller HK, Carroll RK, Burda WN, Krute CN, Davenport JE, Shaw LN. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σS protects against both intracellular and extracytoplasmic stresses in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(16):4342–54.

Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;30:122–32.

DeFrancesco AS, Masloboeva N, Syed AK, DeLoughery A, Bradshaw N, Li G-W, Gilmore MS, Walker S, Losick R. Genome-wide screen for genes involved in eDNA release during biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(29):E5969–78.

Gimza BD, Larias MI, Budny BG, Shaw LN. Mapping the global network of extracellular protease regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. mSphere. 2019;4(5):e00676.

Herrero A, Flores E. Genetic responses to carbon and nitrogen availability in Anabaena. Environ Microbiol. 2019;21(1):1–17.

Liu T, Golden JW, Giedroc DP. A zinc(ii)/lead(ii)/cadmium(ii)-inducible operon from the cyanobacterium Anabaena is regulated by aztr, an α3n arsr/smtb metalloregulator. Biochemistry-us. 2005;44(24):8673–83.

Ludwig M, Chua TT, Chew CY, Bryant DA. Fur-type transcriptional repressors and metal homeostasis in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1217.

Rohac R, Crack JC, de Rosny E, Gigarel O, Le Brun NE, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A. Structural determinants of DNA recognition by the NO sensor NsrR and related Rrf2-type [FeS]-transcription factors. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):769.

TAKEDA K, AKIMOTO C, KAWAMUKAI M. Effects of the Escherichia coli sfsA gene on mal genes expression and a DNA binding activity of SfsA. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65(1):213–7.

Kornacki JA, Balderes PJ, Figurski DH. Nucleotide sequence of korB, a replication control gene of broad host-range plasmid RK2. J Mol Biol. 1987;198(2):211–22.

Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk T, Szatraj K, Kosiorek K. GlaR (YugA)—a novel RpiR-family transcription activator of the Leloir pathway of galactose utilization in Lactococcus lactis IL1403. MicrobiologyOpen. 2019;8(5):e00714.

Ravcheev DA, Khoroshkin MS, Laikova ON, Tsoy OV, Sernova NV, Petrova SA, Rakhmaninova AB, Novichkov PS, Gelfand MS, Rodionov DA. Comparative genomics and evolution of regulons of the LacI-family transcription factors. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:294.

Liu J, Chen Y, Li L, Yang E, Wang Y, Wu H, Zhang L, Wang W, Zhang B. Characterization and engineering of the Lrp/AsnC family regulator SACE_5717 for erythromycin overproduction in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;46(7):1013–24.

Huisman TT, de Graaf FK. Negative control of fae (K88) expression by the ‘global’ regulator Lrp is modulated by the ‘local’ regulator FaeA and affected by DNA methylation. Mol Mircrobiol. 1995;16:943–53.

Riordan JT, Mitra A. Regulation of Escherichia coli pathogenesis by alternative sigma factor n. EcoSal Plus. 2017, 7(2).

Tomoyasu T, Takaya A, Isogai E, Yamamoto T. Turnover of FlhD and FlhC, master regulator proteins for Salmonella flagellum biogenesis, by the ATP-dependent ClpXP protease. Mol Mircrobiol. 2003;48(2):443–52.

Leyn SA, Rodionov DA. Comparative genomics of DtxR family regulons for metal homeostasis in Archaea. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(3):451–8.

Sun D, Zhu J, Chen Z, Li J, Wen Y. SAV742, a novel Arac-family regulator from Streptomyces avermitilis, controls avermectin biosynthesis, cell growth and development. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36915.

Hou S, Tong Y, Yang H, Feng S. Molecular insights into the copper-sensitive Operon Repressor in Acidithiobacillus caldus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87:AEM0066021.

Grinberg I, Shteinberg T, Gorovitz B, Aharonowitz Y, Cohen G, Borovok I. The Streptomyces NrdR transcriptional regulator is a zn ribbon/ATP cone protein that binds to the promoter regions of class Ia and class II ribonucleotide reductase operons. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(21):7635–44.

Zeng LR, Xie JP. Molecular basis underlying LuxR family transcription factors and function diversity and implications for novel antibiotic drug targets. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(11):3079–84.

Isom CE, Menon SK, Thomas LM, West AH, Richter-Addo GB, Karr EA. Crystal structure and DNA binding activity of a PadR family transcription regulator from hypervirulent Clostridium difficile R20291. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):231.

Takashima K, Nagao S, Kizawa A, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Hihara Y. The role of transcriptional repressor activity of LexA in salt-stress responses of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17393.

Deochand DK, Grove A. MarR family transcription factors: dynamic variations on a common scaffold. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;52(6):595–613.

Colclough AL, Scadden J, Blair JMA. TetR-family transcription factors in Gram-negative bacteria: conservation, variation and implications for efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):731.

Cheng Y-I, Lin Y-C, Leu J-Y, Kuo C-H, Chu H-A. Comparative analysis reveals distinctive genomic features of Taiwan hot-spring cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus sp. TA-1. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:932840–0.

Kees ED, Murugapiran SK, Bennett AC, Hamilton TL. Distribution and genomic variation of Thermophilic Cyanobacteria in Diverse Microbial mats at the Upper temperature limits of photosynthesis. mSystems. 2022;7(5):e0031722.

Jahodářová E, Dvořák P, Hašler P, Holušová K, Poulíčková A. Elainella gen. nov.: a new tropical cyanobacterium characterized using a complex genomic approach. Eur J Phycol. 2018;53(1):39–51.

Kopf M, Klähn S, Scholz I, Matthiessen JKF, Hess WR, Voß B. Comparative analysis of the primary transcriptome of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 2014;21(5):527–39.

Gunnelius L, Tuominen I, Rantamäki S, Pollari M, Virjamo V, Tyystjärvi E, Tyystjärvi T. SigC sigma factor is involved in acclimation to low inorganic carbon at high temperature in Synechocystis Sp. PCC 6803 Microbiology. 2009;156:220–9.

Liang W, Postier B, Burnap R. Alterations in global patterns of gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to inorganic carbon limitation and the inactivation of ndhr, a lysr family regulator. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5739–51.

Foster A, Patterson C, Pernil R, Hess C, Robinson N. Cytosolic Ni(II) sensor in cyanobacterium: Nickel detection follows nickel affinity across four families of metal sensors. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12142–51.

Weiyu S, Shasha Z, Zhengke L, Dai G, Liu K, Chen M, Qiu B-S. Sycrp2 is essential for twitching motility in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Bacteriol. 2018;200:JB00436–00418.

Paithoonrangsarid K, Shoumskaya MA, Kanesaki Y, Satoh S, Tabata S, Los DA, Zinchenko VV, Hayashi H, Tanticharoen M, Suzuki I, et al. Five histidine kinases perceive osmotic stress and regulate distinct sets of genes in Synechocystis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53078–86.

Chen L, Ren Q, Wang J, Zhang W. Slr1909, a novel two-component response regulator involved in acid tolerance in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. In: Stress and Environmental Regulation of Gene Expression and Adaptation in Bacteria 2016: 935–43.

Chen L, Zhu Y, Song Z, Wang J, Zhang W. An orphan response regulator Sll0649 involved in cadmium tolerance and metal homeostasis in photosynthetic Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Proteom. 2014;103:87–102.

Moreira D, Tavera R, Benzerara K, Skouri-Panet F, Couradeau E, Gérard E, Fonta CL, Novelo E, Zivanovic Y, López-García P. Description of Gloeomargarita lithophora gen. nov., sp. nov., a thylakoid-bearing, basal-branching cyanobacterium with intracellular carbonates, and proposal for Gloeomargaritales Ord. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67(3):653–8.

Nagy C, Vass I, Rákhely G, Vass IZ, Tóth A, Duzs Á, Peca L, Kruk J, Kós P. Coregulated genes link sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase and arsenic metabolism in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:3430–40.

Hein S, Scholz I, Voß B, Hess WR. Adaptation and modification of three CRISPR loci in two closely related cyanobacteria. RNA Biol. 2013;10(5):852–64.

Muro-Pastor A, Herrero A, Flores E. Nitrogen-regulated group 2 sigma factor from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 involved in survival under nitrogen stress. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1090–5.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970092, 32071480, and 3221101094), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2021YFS0005) and Tenure-Track Fund to Maurycy Daroch. Funding bodies had no influence on the way study was conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D. and J.T. conceived and designed research. J.T., Z.H. and J.Z. performed the analysis and interpreted data. All authors participated in preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

: Genome annotations of thermophilic cyanobacteria

Supplementary Material 2

: Predicted TF genes in the genome of cyanobacteria studied

Supplementary Material 3

: Habitat and number of TF genes of cyanobacteria studied

Supplementary Material 4

: Phylogenetic inference of 16S rRNA gene sequences representing 128 cyanobacterial strains

Supplementary Material 5

: Ortholog table of TFs in strains from each family

Supplementary Material 6

: Blastp results between TFs of thermophilic cyanobacteria and TFs of Synechocystis PCC 6803

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Hu, Z., Zhang, J. et al. Genome-scale identification and comparative analysis of transcription factors in thermophilic cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics 25, 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-09969-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-09969-7