Abstract

Background

Insects are an important reservoir of viral biodiversity, but the vast majority of viruses associated with insects have not been discovered. Recent studies have employed high-throughput RNA sequencing, which has led to rapid advances in our understanding of insect viral diversity. However, insect genomes frequently contain transcribed endogenous viral elements (EVEs) with significant homology to exogenous viruses, complicating the use of RNAseq for viral discovery.

Methods

In this study, we used a multi-pronged sequencing approach to study the virome of an important agricultural pest and prolific vector of plant pathogens, the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae. We first used rRNA-depleted RNAseq to characterize the microbes found in individual insects. We then used PCR screening to measure the frequency of two heritable viruses in a local aphid population. Lastly, we generated a quality draft genome assembly for M. euphorbiae using Illumina-corrected Nanopore sequencing to identify transcriptionally active EVEs in the host genome.

Results

We found reads from two insect-specific viruses (a Flavivirus and an Ambidensovirus) in our RNAseq data, as well as a parasitoid virus (Bracovirus), a plant pathogenic virus (Tombusvirus), and two phages (Acinetobacter and APSE). However, our genome assembly showed that part of the ‘virome’ of this insect can be attributed to EVEs in the host genome.

Conclusion

Our work shows that EVEs have led to the misidentification of aphid viruses from RNAseq data, and we argue that this is a widespread challenge for the study of viral diversity in insects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The last decade has transformed our understanding of the viral communities associated with insects, the most abundant and diversified animal group [1,2,3,4]. Insect viruses have been primarily studied in the context of vector-borne pathogens, which are transmitted horizontally between insect vectors and amplifying hosts, and often have medical or agricultural relevance. Other viruses, however, only replicate within the insect and are maintained in natural populations through horizontal and/or vertical transmission. These insect-specific viruses have important impacts on host biology [5,6,7], but much work remains to be done to describe insect-specific viral diversity and to uncover the hidden role viruses play in insect phenotypes and evolution [8,9,10].

To address this gap, researchers have employed high-throughput approaches to viral discovery, including next-generation sequencing and analysis of RNA [2, 11,12,13,14,15]. However, there are several serious limitations to this approach. For example, RNAseq data does not distinguish between reads that come from viruses infecting insect cells or from microbes infecting an organism ingested by the insect. Another potential challenge with using RNAseq for viral discovery is that insects often harbor fragments of viral sequences in their genomes. The endogenous viral elements (EVEs) described to date have homology with multiple clades of single- and double-stranded DNA and RNA viral families [16]. We have a limited understanding of the role EVEs are playing in insect biology, but transcriptionally active EVEs have been shown to play functional roles in regulating host genome stability and as an antiviral defense against exogenous viruses [17,18,19]. EVEs are remarkably common across insects [20], and thus EVEs could represent a widespread challenge for the use of RNAseq in viral discovery.

Aphids (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) are hosts to diverse viruses, including plant pathogens with agricultural significance and insect-specific viruses [21, 22]. Recent studies have used metatranscriptome sequencing to describe viral diversity in aphids [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], and have found insect-specific DNA viruses in the family Parvoviridae and RNA viruses in the Bunyaviridae, Dicistroviridae, Flaviviriridae, Iflaviridae, and Mesoniviridae families [21]. The potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas, 1878) is an important cosmopolitan agricultural pest that infests tomatoes, potatoes, and other economically important crops [30]. M. euphorbiae is also an important vector of plant viruses (Families Bromoviridae, Closteroviridae, Geminiviridae, Potyviridae, and Solemoviridae) and was recently shown to host several insect-specific viruses belonging to the families Flaviviridae (genus Flavivirus) and Parvoviridae (genus Ambidensovirus) [24, 31, 32]. Despite M. euphorbiae's economic importance, no genomic resources were available outside body and salivary gland transcriptomes [24, 33, 34].

The genomes of multiple aphid species have been shown to harbor EVEs that mediate growth, development, and wing plasticity [35,36,37,38,39]. In this study, we use next-generation sequencing and analysis to show that aphid EVEs have led to the misidentification of aphid viruses from RNAseq data. First, we used RNAseq to characterize the microbial diversity of field-collected M. euphorbiae adults, and found sequences from two insect-specific viruses that have been identified previously in aphids, a Flavivirus and Ambidensovirus. Then, we generated a high-quality draft genome sequence for this species. Our genome showed that insect-specific Ambidensoviral hits corresponded to transcriptionally active EVEs, indicating that a previously described virus is actually an endogenous viral element in the M. euphorbiae genome. These EVEs have homology to the ‘APNS’ genes in the related pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum), which resulted from a lateral gene transfer from a Densovirus and play a role in the plastic production of aphid wings [37]. Our study illustrates how careful analysis using multiple methods is needed to untangle insect viromes from EVEs and furthers our understanding of the surprisingly widespread presence of Densoviral EVEs in aphid genomes.

Methods

Aphid collection

We collected asexual winged and wingless female M. euphorbiae adults from cultivated tomato plants (var Husky Cherry Red) in Knoxville, TN, USA, between April and June 2021 and 2022. We stored individual aphids in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at -80 °C until processing. For species taxonomy validation, M. euphorbiae (NCBI TaxID: 13131), we used COI barcoding (LCO1490 5'-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3' and HCO2198 5'-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3'), sanger sequencing, and comparisons of our COI sequences to the Barcode of Life Data System (https://www.boldsystems.org/) [40]. Our COI barcode sequence was uploaded to NCBI with accession number OQ588703. All M. euphorbiae samples were labeled as “Me” followed by a consecutive number.

Cultivation of M. euphorbiae strain Me57

To establish a colony of M. euphorbiae in the laboratory, we used a single asexual female collected in 2021. After colonization, we maintained this line on tomato plants (Husky Cherry Red) at 20 °C 16L:8D. We screened the line for the seven species of facultative symbionts found in aphids using established PCR protocols [41, 42]. For this screen, we extracted DNA using ‘Bender buffer’ and ethanol precipitation as in previous studies [43, 44]. We then used PCR with species-specific primers [42, 45] to screen for Hamiltonella defensa, Fukatsuia symbiotica (previously referred to as X-type), Regiella insecticola, Rickettsia sp., Ricketsiella sp., Serratia symbiotica, and Spiroplasma sp. following the recommended thermal protocol (94 °C for 2 min, 11 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 56 °C (declining 1 °C each cycle) for 50 s, 72 °C for 30 s, 25 cycles of 94 °C for 2 min, 45 °C for 50 s, 72 °C for 2 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min).

RNA extraction and sequencing

We randomly selected four M. euphorbiae samples (Me022, Me112, Me152, Me202) for further analysis. We homogenized single aphids with a pestle in 500 µL of TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) to extract total RNA using BCP (1-bromo-3-chloropropane; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with isopropanol precipitation. We used the Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Genetics Inc., Seattle, WA, USA) to improve the purity and to remove gDNA using DNAse I. We then performed metatranscriptome sequencing at Novogene (Novogene Corporation Inc., Sacramento, CA, USA). Library preparation was conducted using ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion by Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo-Zero Plus and NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit (Zymo Genetics, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). The libraries were sequenced to approximately 9 billion base pairs (bp) per sample with 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina NovaSeq platform. Raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject ID PRJNA942253 with BioSample accessions SAMN33770905-SAMN33770908, and data accessions SRR23870213-SRR23870216.

Microbial analysis using CZ ID

We assessed the success of ribosomal reduction in the metatranscriptome libraries using riboPicker [46] and the reference database SILVA_138 [47] (S1 Table). We then used the CZ ID platform pipeline V7.1 (https://czid.org) [48], a cloud-based, open-source bioinformatics platform designed to detect microbes from metagenomic data. We removed host-specific reads (STAR host subtraction) using the Acyrthosiphon pisum genome [49], trimmed adapters using Trimmomatic [50], removed low-quality reads with PriceSeqFilter [51], and aligned the remaining reads to the NCBI NT and NR databases using Minimap2 [52] and Diamond [53]. In parallel, short reads were de novo assembled using SPADES [54] and mapped back to the resulting contigs using bowtie2 [55] to identify the contig to which each raw read belongs. We used the CZ ID water background model, which evaluates the significance (z-scores) of relative abundance estimates for microbial taxa in each sample. Potential bacterial reads were distinguished from contaminating environmental sequences by establishing z-score metrics ≥ 10, alignment length over 50 matching nucleotides (NT L ≥ 50), and a minimum of five reads per million aligning to the reference protein database (NR rPM ≥ 5). Potential viruses were established by z-score metrics of ≥ 1, NT L ≥ 50, NR rPM ≥ 1, and a minimum of five reads per million aligning to the reference nucleotide database (NT rPM ≥ 5) [48, 56, 57]. Bacterial and viral contigs were confirmed with BLASTX and BLASTN manual searches. Only annotated microbial hits with revised taxonomy through manual BLAST searches were used for further analysis. The “Macrosiphum euphorbiae” project is publicly available via CZ ID.

Analysis of the Flavivirus MeV-1 genome

We used the CZ ID viral consensus genomes pipeline to build a consensus genome from the sample with Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 1 (MeV-1) present at high levels (Me202). In short, contigs were aligned to the reference MeV-1 genome (NCBI Entry KT309079.1) using minimap2 [52] and then trimmed using TrimGalore (Phred score < 20) [58]. The consensus genome was generated with iVar consensus using a depth of five or more reads [59]. Our consensus genome was deposited into the NCBI with accession number: OQ504571.

Analysis of the Ambidensovirus using de novo assembly and TRAVIS

We conducted an additional screening and viral genome assembly of potential Ambidensoviruses using de novo transcriptome assemblies as follows. We used Trimmomatic v.0.39 [50] to trim the sequence adapters and filtered low-quality/complexity reads, and we assessed for post-trimming quality using FastQC v.0.11.9 [60]. Then, we used Trinity v.2.14 [61] to de novo assemble the remaining reads. We used TRAVIS (v.20221029, https://github.com/kaefers/travis) to scan the assembled transcriptomes for Densovirus-like sequences. We built the reference database to the Parvoviridae viral family including the accepted Densovirinae viral species by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) by 29th Oct 2022 (S2 Table), extracted open reading frames between 100 and 2000 amino acids from the assembled transcriptomes, and screened using HMMER v3.3.1 [62], MMSeqs2 [63], BLASTP v2.12.0 [64], and Diamond v2.0.15 [53]. We set the e-value cutoff at 1 × 10–6, where applicable. All hits were again searched with Diamond against the non-redundant protein database (NCBI, downloaded on 29 Oct 2022).

MeV-1, MeV-2, and Hamiltonella defensa screening

Like all aphids, M. euphorbiae hosts an obligate heritable bacterial symbiont called Buchnera aphidicola that synthesizes amino acids missing from the aphid’s diet of plant phloem, and can also harbor several other facultative symbiotic bacteria (listed above) [45]. To screen for these microbes, we used 1 μg of total RNA extracted (as above) from each of the 23 adults collected during 2022 for cDNA synthesis with iScript cDNA synthesis kit, which uses random hexamer primers (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). To screen for the Flavivirus, Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 1 (MeV-1), we used 100 ng of cDNA, the primers MevirF1 (5'-GTACACTTGCCTTACCTTACTGT-3') and MevirR1b (5'-AACACGGGTCACGACCTTAG-3'), and the PCR conditions previously described [32]. To screen for the Ambidensovirus, Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 2 (MeV-2), we used 100 ng of cDNA, the MeV2-F (5'-CCGGATGACAAATCCCACGA-3') and MeV2-R (5'-AATAGGCGCAGAGATGGACG-3') primers, and the recommended PCR conditions [24]. In addition, we extracted DNA from our laboratory aphid colony Me57 (as above) and used 40 ng of genomic DNA to screen for MeV-2. The aphid Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) was used as internal control (primers G3PDH_F (5'-CGGGAATTTCATTGAACGAC-3') and G3PDH_R (5'- TCCACAACACGGTTGGAGTA-3') [37]). Moreover, we used 200 ng of the cDNA previously synthesized for MeV-1 and MeV-2 screening and the protocols for Hamiltonella defensa PCR screening (as described above) to evaluate the proportion of field-collected aphids harboring this bacterial symbiont (S3 Table). We used a non-parametric (Spearman) correlation to investigate the potential interaction between Hamiltonella and MeV-1.

DNA extraction and sequencing

We pooled seven genetically identical adult unwinged aphids from our Me57 laboratory line and isolated genomic DNA (gDNA) using a phenol/chloroform extraction. We then sheared the gDNA to approximately 20 kb fragments using Covaris G-tubes (Covaris LLC., Woburn, MA, USA) at 4,200 RMP for 1 min, followed by tube inversion. For library preparation, we used the NEB Next PPFE repair kit with Ultra II end prep reaction (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) under the recommended conditions and Nanopore ligation sequencing kit SQK-LSK110. For sequencing, we used a Nanopore R9.4.1 (FLO-MIN106D) flow cell and a MinION MIN-101B sequencing device (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). We ran the flow cell for 24 h, followed by a wash with Flow Cell Wash Kit (EXP-WSH004); we then reloaded the flow cell with a second library prep and ran the sequencer for an additional 48 h. We stopped the second sequencing run at 72 h (~ 22 Gbps of sequencing). In addition, we performed an additional 5.3 Gb of 150 bp paired-end sequencing to polish the assembly on an Illumina NovaSeq platform. DNA was extracted as above, and library prep and sequencing were performed by Novogene Inc. Raw reads were filtered for low quality and adapter contamination by Novogene Inc.

M. euphorbiae whole genome assembly

We used Guppy (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) for base-calling and quality trimming raw reads. For the removal of Buchnera reads, we used minimap2 v.2.24 [52] in conjunction with SAMtools v.1.15.1 [65] to map our reads against the Buchnera aphidicola (strain Macrosiphum euphorbiae) genome (NCBI accession NZ_CP029205) and the corresponding plasmids (NCBI accession number NZ_CP029203 and NZ_CP029204). We only kept unmapped reads for aphid genome assembly. We assembled Nanopore reads using CANU v.2.0 [66] with an estimated genome size of 541 Mbp. We removed allelic variants from the assembly using purge_haplotigs v.1.1.2 [67], first by mapping reads to the assembly using minimap2 v2.24-r1122 with Samtools v.1.15.1 and manually choosing cutoffs for haploid vs. diploid coverage based on a histogram plot (v -l 5 -m 27 -h 60), and then by purging duplicated contigs based on coverage level (-j 80 -s 50). For assembly polishing, we used the Illumina reads after quality assessment using FastQC V0.11.9 [60]. Then we used these reads to polish the purged assembly using Pilon v.1.24 with default parameters [68]. We used BlobTools2 [69] to identify remaining contaminating contigs. For this, we used blast results obtained from the BLASTN function against the NT database using blast plus v.2.12.0 [70], read coverage obtained by mapping the Illumina reads to the assembly using minimap2 v.2.24 [52], and GC content in this analysis. Based on these results, we removed all the short contigs with strong homology to the plant genus Solanum (which includes the tomato host plant species of M. euphorbiae) as we suspect these contigs were assembled from host plant contamination in the guts of sequenced aphids. We also removed two short contigs with homology to other bacterial contaminants such as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas sp. We removed a contig nearly identical to the pLeu plasmid found in Buchnera aphidicola. We also removed small portions of two larger contigs, which matched the Buchnera genome and had been misassembled into the larger contigs. The final annotation was assessed using BUSCO v.5.3.2 [71] with the MetaEuk gene predictor [72] implemented in galaxy.org, using the hemiptera_odb10 (2020–08-05) lineage dataset. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JARHUA000000000. The version described in this paper is version JARHUA010000000.The raw Nanopore (SRR23851809) and Illumina reads (SRR23919025) associated with the genome are available through the Sequence Read Archive, and the finished assembly is available with accession number SRR23851809.

Characterizing endogenous viral elements in the M. euphorbiae genome

DNA Illumina raw reads were used as input to the CZ ID platform pipeline V7.1 (https://czid.org) and a z-score metrics of ≥ 1 and NT L ≥ 50 as described above [48, 56]. Additionally, to screen for actively transcribed Densovirus-like EVEs in the M. euphorbiae genome, we used BLASTN searches using the seven viral hits provided as individual Trinity contigs flagged by TRAVIS (sequences available as S1 file) against the genome scaffolds. All non-redundant hits from these searches with e-values < 1.10–3 were extracted and used in further analyses [35].

Results

Analysis of non-host sequences detected in single aphids

We used the pea aphid (A. pisum) genome to subtract host reads from our transcriptome data set. On average, 81.8% of the reads mapped to A. pisum and were removed from further analysis (S1 Table). For each sample, we then analyzed the remaining reads as the overall proportion of assembled reads assigned to bacterial, eukaryotic, and viral taxa (public project “Macrosiphum euphorbiae” at https://czid.org). Bacterial taxa dominated the microbial signature (Fig. 1A), and as expected, the highest number of hits matched the aphid obligate symbiont Buchnera aphidicola with over 45,000 reads per million aligning to the nucleotide database (NT rPM > 45,000). Hits to an aphid facultative symbiont (Hamiltonella defensa) were found in two samples (NT rPM > 8,700). Moreover, one sample (Me152) showed a strong signature of bacterial contaminants (E. coli, Pseudomonas, Halomonas, and Agrobacterium) that are commonly present in soil and plant surfaces.

Details of the per sample breakdown of reads aligning to specific bacterial (A), eukaryotic (B), and viral (C) taxa. Reads per million aligned to the nucleotide database (NT rPM) was used as the quantitative metric in the heatmaps (see Table S5 for metric details)

In terms of eukaryotes (Fig. 1B), we found hits to Solanaceae, which includes the host plant species of M. euphorbiae, and Brachonidae parasitoid wasps (Insecta: Hymenoptera) in two samples (NT rPM > 18,000). M. euphorbiae is known to be parasitized by hymenopterous wasps belonging to the superfamilies Ichneumonoidea (Braconidae) and Chalcidoidea [73]. In addition, there were some M. euphorbiae species-specific reads remaining, which did not map to the pea aphid reference genome but showed some homology to other aphid species (Insecta: Hemiptera).

Regarding the virome, we detected the presence of two insect-specific viruses in our metatranscriptome data (Fig. 1C). The highest number of hits matched a previously described insect-specific Flavivirus, called Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 1 (MeV-1) [32], which was detected in two samples (NT rPM = 234 and 4055 for Me112 and Me202, respectively). We also detected viral hits to an insect-specific Ambidensovirus (Me202 and Me152; NT rPM 1.3 and 1.8, respectively). Other viral reads in our samples included a Bracovirus in one of the samples that was parasitized with the Brachonidae wasp (Me202; NT rPM = 1) and a Tombusvirus (Me152; NT rPM = 2.9), a family of plant pathogenic viruses with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome. Lastly, we detected two phage genera, the Hamitonella-specific phage A. pisum secondary endosymbiont (APSE; NT rPM > 310), in the same samples found positive for this symbiont (Me112 and Me202). We also found Acinetobacter phage (NT rPM 0.5–18) in all samples, which is a bacteriophage highly prevalent in the environment [74].

Analysis of insect-specific viruses

Five assembled contigs aligned to the MeV-1 reference genome (NCBI accession KT309079) with nucleotide identity ranging between 85.8–97.2% (Fig. 2A). Transcriptome data from our field samples retrieved 17,397 informative nucleotides allowing the assembly of a nearly complete genome for MeV-1. Our MeV-1 consensus genome has a coverage breadth of 79% and a coverage depth of 673.2x (NCBI accession OQ504571) (S1 Figure). This single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome contains a single large ORF encoding a polyprotein of 7,333 amino acids, which is subsequently processed to generate structural and non-structural proteins [75]. Previous analysis indicated that the polyprotein motifs of MeV-1 helicase, methyltransferase, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) are similar to domains in other Flaviviruses (family Flaviviridae) [21, 32]. The characteristic secondary structures (RNA stem-loop) in Flavivirus genomes most likely contributed to the 5,283 missing bases in our MeV-1 consensus genome assembly [76].

In addition, we detected two contigs with 80% nucleotide similarity to the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of Dysaphis plantaginea densovirus (DplDNV), a single-stranded DNA insect-specific Ambidensovirus (family Parvoviridae) (S2 File). Due to the lack of a publicly available genome or partial viral sequences of Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 2 (MeV-2), an Ambidensovirus previously described in the same aphid species [24], we were not able to explore the homology between both viruses. Therefore, we conducted a more extensive analysis of our RNAseq data using TRAVIS, a consistency-based virus detection pipeline for sensitive mass screening of transcriptomic data directed toward Parvoviridae proteins. In general, sequence identity between Densovirinae (a subfamily of viral species exclusively infecting arthropods) is very low, with some pairs sharing < 15% amino acid identity some of their viral proteins. However, Densoviruses often express conserved domains in the NS1 and VP proteins, which are useful for phylogenetic inferences [77]. We found seven Densovirus-like hits (S1 File) and used them to construct a hypothetical genome assembly using DplDNV (NCBI accession NC034532) as a reference (Fig. 2B). We found three contigs with 68.8% to 81.3% nucleotide similarity to the non-structural ORF1 (encoding for the NS1 protein) and two contigs with 68.8% to 86.2% nucleotide similarity to the structural ORF (encoding for the VP protein). None of the assembled contigs had either nucleotide or amino acid similarity to DplDNV ORF2 (encoding for the NS2 protein). Importantly, all densoviral NS1-like sequences also had 72% to 85% nucleotide similarity to the pea aphid APNS-2 (NCBI accession NC042493.1 and NC042494.1), an endogenous viral element (EVE) that contributes to wing phenotypic plasticity in this species [37].

Insect-specific virus frequency in natural populations

To further investigate the infection frequency of MeV-1 and MeV-2 infections in natural populations, we used a PCR approach to screen 23 individual adult aphids collected in 2022 as well as aphids from our colonized Macrosiphum line (Me57). We found that only 13 field-collected aphids were positive for MeV-1 (54.2%) and 21 aphids (87.5%) were positive for MeV-2, including the laboratory established line (Me57) (Fig. 3). We also tested the cDNA of field-collected aphids (previously screened for MeV-1) for the presence of Hamiltonella defensa and found that 54.2% of the aphids (n = 13) were harboring this bacterial symbiont. We found that 41.7% of individuals (n = 10) tested positive for both the Flavivirus and Hamiltonella (Fig. 3), but this association was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.078; r = 0.375).

Genome sequencing for analysis of endogenous viral elements (EVEs)

Since our laboratory line (Me57) was found to be PCR positive for MeV-2, we used the CZ ID platform to identify viral taxa using the Illumina DNA reads from our colonized Me57 aphid line. Surprisingly, we detected only a single contig with a low number of Ambidensoviral hits (NT rPM > 0.329), which also showed 79.0% nucleotide similarity to the DplDNV NS1 and 84.34% nucleotide similarity to an uncharacterized genomic transcript in pea aphids (NCBI accession XM_029492170.1). Since both our transcriptomic (Fig. 2B) and genomic data were unable to recover a complete or near-to-complete Ambidensovirus genome, we suspected that these viral reads could correspond instead to actively transcribed EVEs, as previously reported in other closely related aphid species [35, 37].

To determine with certainty whether the Ambidensoviral hits found in our transcriptome data corresponded to an actively transcribed EVE, we assembled the first M. euphorbiae genome publicly available. We obtained a total of 4,223,264 nanopore reads (at an average of 5.21 kb) and 35,578,886 Illumina reads (PE 150 bp) from sequencing. After assembly, haplotig purging, polishing, and manual removal of plant and bacterial contigs, our assembly contained 2,176 contigs with an N50 length of 665 kb and a total length of 545.7 Mb (Fig. 4A). M. euphorbiae has a similar GC content (29.96%; Fig. 4B) to other sequenced aphids (e.g., Acyrthosiphum pisum at 29.6%, Myzus persicae at 30.1%, and Aphis glycines at 27.8%) [78, 79]. The size of our assembly is close to a recent estimation of the M. euphorbiae genome size based on flow cytometry which was estimated at 531.7 Mb [78]. Similarly, an analysis of single-copy orthologs showed our assembly contains 98.5% complete BUSCOs, with 94% present in single copies and 4.5% duplicated (Fig. 4C). An additional 1.2% of BUSCOs are fragmented, and 0.3% are missing. Together these results suggest that this draft of the genome is highly complete.

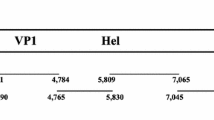

We then used this genome as a reference to screen for the seven individual Trinity contigs flagged by TRAVIS as potential Ambidensovirus in our previous analysis (S1 File). Initially, we selected hits with e-values < 1.10–3 [35]; however, most of the 3,044 hits represent shorter sequences rather than the actual transcript length (S4 Table); therefore, we restricted the search to matches consistently to the entire length of each transcript and e-values = 0 (Table 1). No full-length hits in the genome were found for the two largest viral contigs (contig3 and contig4); instead, the best hits for these two contigs corresponded to 16–17% of the total length. In insects, the EVE repertoires vary between distinct populations of a given species and, in some cases, even between individuals within the same population [80]. This phenomenon potentially explains why all the field aphid samples (n = 3) that tested negative for MeV-2 by PCR amplified a product of approximately 500 bp, which is about half of the expected size reported for the primers used. Given that the genome assemblies and RNAseq data sets were derived from different aphid strains, it is not surprising the wide range of partial-length Ambidensoviral hits obtained in our analysis. However, we are confident that five full-length viral transcripts are constitutively expressed from three regions of the M. euphorbiae genome (tig00030708_pilon, tig00029914_pilon, and tig00027226_pilon).

Discussion

RNAseq is becoming an essential tool for virus discovery. Our study illustrates how endogenous viral elements in host genomes can be an obstacle to using RNAseq for characterizing viral diversity in arthropods. We used rRNA-depleted RNAseq along with bioinformatic tools to characterize the virome of an important insect pest species, the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae. Our analysis found sequences from two insect-specific viruses from the genus Ambidensovirus and Flavivirus described in previous RNAseq studies [24, 32]. However, only by sequencing and assembling the genome of this insect were we able to demonstrate that the previously described Ambidensovirus is a transcriptionally active EVE rather than an exogenous virus. Endogenous viral elements are abundant in arthropod genomes, and thus our study illustrates how EVE sequences in RNAseq studies are an important consideration for future studies of viral diversity in arthropods.

The EVEs we describe in M. euphorbiae have significant homology with those recently described in the pea aphid. It was recently shown that two copies of a transcribed densoviral non-structural protein 1 (termed the “A. pisum non-structural” or “APNS” genes) are upregulated in response to crowded conditions and are functionally linked to the plastic production of wings [37]. These genes originated from a lateral gene transfer from Dysaphis plantaginea densovirus (DplDNV), which, when infecting rosy apple aphids, causes their host to develop wings in greater proportion than non-infected aphids [81]. It appears that the function of these viral genes had been conserved after endogenization but additional data is needed to decipher the role they these EVEs are playing in M. euphorbiae. Together with recent findings, our data show that the APNS genes are widespread through the tribe Macrosiphini [35, 37, 39, 82], raising interesting questions about the origins of these EVEs in this phylogenetic group and their role in host biology.

Endogenization of Parvoviruses (including Ambidensovirus) may be favored by the double-stranded DNA intermediate that occurs during nuclear replication, the endonuclease activity of NS1 protein, and the eukaryote double-stranded break repair mechanism [83, 84]. Previous studies have estimated that around 10% of the parvoviral sequences described in animals are likely integrated into host genomes [77]. In most cases, the EVE status of Parvovirus-like sequences remain uncertain due to unavailable or incomplete genomes for those species in which transcriptome data is available [77]. Importantly, multiple recent studies have used RNAseq data to describe the presence of aphid-specific Densoviruses [23, 85]. These studies often rely only on partial sequences of the one viral protein that is most susceptible to endogenization (NS1). As demonstrated by our results, NS1 viral transcripts do not always indicate that the reported high frequency infections are produced by an exogenous Ambidensovirus, and these results should be interpreted with caution in future studies.

Lastly, our study sheds light on the biology of MeV-1, an insect-specific Flavivirus (family Flaviviridae), previously characterized by RNAseq studies along with replication intermediaries (dsRNA) of M. euphorbiae populations collected in France [32]. We found that this virus, contrary to previous reports, is present in a North American population of M. euphorbiae, and we found that it is highly prevalent in our samples. By assembling a near-to-complete genome of MeV-1 from our RNAseq data and following the criterion to define Flavivirus species via nucleotide sequence comparisons [86], we consider that our local aphid population is infected with the same viral species (as it shared over 84% pairwise nucleotide homologies with the reference virus) but a distinct viral strain (4% nucleotide sequence difference). No obvious infection symptoms or abnormal phenotypes were observed in MeV-1 positive aphids. Future studies are needed to determine what phenotypic effects this virus has on its host.

Since EVEs are common in insect genomes [18], our results highlight a widespread challenge in studying insect viromes from RNAseq data. In future studies, it will be important to combine sequencing methodologies along with careful consideration of the biological characteristics and genome structure of putative novel viruses discovered. In aphids and other widely studied insects, the development of cultured cell lines is essential to isolate viral species described by sequence-based methods, to characterize viral replication, and to perform large-scale virus production that will facilitate future investigation of the complex interactions between insect-specific viruses and their hosts [21].

Conclusions

We show that aphid EVEs have led to the misidentification of aphid viruses from RNAseq data. EVEs are common in insect genomes, and our results highlight a widespread challenge in studying insect viromes. We suggest that combining sequencing methodologies (e.g., RNA and whole genome sequencing) is necessary to overcome the potential pitfalls of RNAseq-based viral discovery.

Availability of data and materials

Species barcode sequence is available through NCBI accession OQ588703. Sequencing raw reads and genome assembly are available through NCBI BioProject PRJNA942253. Microbial analysis data is available through the CZID Macrosiphum euphorbiae project. MeV-1 genome through NCBI accession OQ504571. Additional sequence data of the viral contigs are included as Supplemental S1 File and S2 File.

Abbreviations

- DplDNV:

-

Dysaphis plantaginea densovirus

- EVEs:

-

Transcribed endogenous viral elements

- gDNA:

-

Genomic DNA

- G3PDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- MeV-1:

-

Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 1

- MeV-2:

-

Macrosiphum euphorbiae virus 2

- NS1:

-

Viral non-structural protein 1

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- RNAseq:

-

High-throughput RNA sequencing

- rPM:

-

Reads per million

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal RNA

- VP:

-

Viral protein

References

Koonin EV, Dolja VV. Metaviromics: a tectonic shift in understanding virus evolution. Virus Res. 2018;246:A1–3.

Zhang Y-Z, Shi M, Holmes EC. Using metagenomics to characterize an expanding virosphere. Cell. 2018;172(6):1168–72.

Greninger AL. A decade of RNA virus metagenomics is (not) enough. Virus Res. 2018;244:218–29.

Stork NE. How many species of insects and other terrestrial arthropods are there on earth? Annu Rev Entomol. 2018;63(1):31–45.

Coatsworth H, Bozic J, Carrillo J, Buckner EA, Rivers AR, Dinglasan RR, et al. Intrinsic variation in the vertically transmitted core virome of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Mol Ecol. 2022;31(9):2545–61.

Longdon B, Jiggins FM. Vertically transmitted viral endosymbionts of insects: do sigma viruses walk alone? Proc R Soc B. 2012;279(1744):3889–98.

Longdon B, Day JP, Schulz N, Leftwich PT, de Jong MA, Breuker CJ, et al. Vertically transmitted Rhabdoviruses are found across three insect families and have dynamic interactions with their hosts. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284(20162381). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2381.

González R, Butković A, Elena SF. Chapter Three - From foes to friends: Viral infections expand the limits of host phenotypic plasticity. In: Kielian M, Mettenleiter TC, Roossinck MJ, editors. Advances in Virus Research. 106: Academic Press; 2020. p. 85–121.

Simmonds P, Aiewsakun P, Katzourakis A. Prisoners of war—host adaptation and its constraints on virus evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(5):321–8.

Mauck KE. Variation in virus effects on host plant phenotypes and insect vector behavior: What can it teach us about virus evolution? Curr Opin Virol. 2016;21:114–23.

Bolling BG, Weaver SC, Tesh RB, Vasilakis N. Insect-specific virus discovery: significance for the arbovirus community. Viruses. 2015;7(9):4911–28.

Li C-X, Shi M, Tian J-H, Lin X-D, Kang Y-J, Chen L-J, et al. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. eLife. 2015;4:e05378.

Käfer S, Paraskevopoulou S, Zirkel F, Wieseke N, Donath A, Petersen M, et al. Re-assessing the diversity of negative strand RNA viruses in insects. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(12):e1008224.

Liu S, Chen Y, Bonning BC. RNA virus discovery in insects. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2015;8:54–61.

Wu H, Pang R, Cheng T, Xue L, Zeng H, Lei T, et al. Abundant and diverse RNA viruses in insects revealed by RNA-Seq analysis: Ecological and evolutionary implications. mSystems. 2020;5(4):e00039–20.

Gilbert C, Belliardo C. The diversity of endogenous viral elements in insects. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2022;49:48–55.

Veglia AJ, Bistolas KSI, Voolstra CR, Hume BCC, Ruscheweyh HJ, Planes S, Allemand D, et al. Endogenous viral elements reveal associations between a non-retroviral RNA virus and symbiotic dinoflagellate genomes. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):566. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-04917-9.

Blair CD, Olson KE, Bonizzoni M. The widespread occurrence and potential biological roles of endogenous viral elements in insect genomes. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2020;34:13–30.

Frank JA, Feschotte C. Co-option of endogenous viral sequences for host cell function. Curr Opin Virol. 2017;25:81–9.

Holmes EC. The evolution of endogenous viral elements. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10(4):368–77.

Guo Y, Ji N, Bai L, Ma J, Li Z. Aphid viruses: a brief view of a long history. Front Insect Sci. 2022;2:846716.

Ray S, Casteel CL. Effector-mediated plant–virus–vector interactions. Plant Cell. 2022;34(5):1514–31.

Feng Y, Krueger EN, Liu S, Dorman K, Bonning BC, Miller WA. Discovery of known and novel viral genomes in soybean aphid by deep sequencing. Phytobiomes J. 2017;1(1):36–45.

Teixeira MA, Sela N, Atamian HS, Bao E, Chaudhary R, MacWilliams J, et al. Sequence analysis of the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae transcriptome identified two new viruses. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0193239.

Kondo H, Fujita M, Hisano H, Hyodo K, Andika IB, Suzuki N. Virome analysis of aphid populations that infest the barley field: the discovery of two novel groups of Nege/Kita-like viruses and other novel RNA viruses. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:509.

Li T, Li H, Wu Y, Li S, Yuan G, Xu P. Identification of a novel Densovirus in aphid, and uncovering the possible antiviral process during its infection. Front Immunol. 2022;13:905628.

Wamonje FO, Michuki GN, Braidwood LA, Njuguna JN, Musembi Mutuku J, Djikeng A, et al. Viral metagenomics of aphids present in bean and maize plots on mixed-use farms in Kenya reveals the presence of three dicistroviruses including a novel Big Sioux River virus-like dicistrovirus. Virol J. 2017;14(1):188.

An X, Zhang W, Ye C, Smagghe G, Wang J-J, Niu J. Discovery of a widespread presence Bunyavirus that may have symbiont-like relationships with different species of aphids. Insect Sci. 2022;29(4):1120–34.

Chang T, Guo M, Zhang W, Niu J, Wang J-J. First report of a Mesonivirus and its derived small RNAs in an aphid species Aphis citricidus (Hemiptera: Aphididae), implying viral infection activity. J Insect Sci. 2020;20(2):14.

Blackman RL, Eastop VF, Museum NH. Aphids on the world's crops: an identification and information guide. Wiley; 2000.

Xu Y, Gray SM. Aphids and their transmitted potato viruses: a continuous challenges in potato crops. J Integr Agric. 2020;19(2):367–75.

Teixeira M, Sela N, Ng J, Casteel CL, Peng H-C, Bekal S, et al. A novel virus from Macrosiphum euphorbiae with similarities to members of the family Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2016;97(5):1261–71.

Planelló R, Llorente L, Herrero Ó, Novo M, Blanco-Sánchez L, Díaz-Pendón JA, et al. Transcriptome analysis of aphids exposed to glandular trichomes in tomato reveals stress and starvation related responses. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20154.

Atamian HS, Chaudhary R, Cin VD, Bao E, Girke T, Kaloshian I. In planta expression or delivery of potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae effectors Me10 and Me23 enhances aphid fecundity. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2013;26(1):67–74.

Clavijo G, van Munster M, Monsion B, Bochet N, Brault V. Transcription of Densovirus endogenous sequences in the Myzus persicae genome. J Gen Virol. 2016;97(4):1000–9.

Jayasinghe WH, Kim H, Nakada Y, Masuta C. A plant virus satellite RNA directly accelerates wing formation in its insect vector for spread. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):7087.

Parker BJ, Brisson JA. A laterally transferred viral gene modifies aphid wing plasticity. Curr Biol. 2019;29(12):2098–103.e5.

Shang F, Niu J, Ding B-Y, Zhang W, Wei D-D, Wei D, et al. The miR-9b microRNA mediates dimorphism and development of wing in aphids. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(15):8404–9.

Liu S, Coates BS, Bonning BC. Endogenous viral elements integrated into the genome of the soybean aphid, aphis glycines. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;123:103405.

Foottit RG, Maw HE, CD VOND, Hebert PD. Species identification of aphids (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae) through DNA barcodes. Mol Ecol Res. 2008;8(6):1189–201.

McLean AHC, Hrcek J, Parker BJ, Mathe-Hubert H, Kaech H, Paine C, et al. Multiple phenotypes conferred by a single insect symbiont are independent. Proc Biol Sci. 1929;2020(287):20200562.

Henry Lee M, Peccoud J, Simon J-C, Hadfield Jarrod D, Maiden Martin JC, Ferrari J, et al. Horizontally transmitted symbionts and host colonization of ecological niches. Curr Biol. 2013;23(17):1713–7.

Bender W, Spierer P, Hogness DS, Chambon P. Chromosomal walking and jumping to isolate DNA from the Ace and rosy loci and the bithorax complex in Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 1983;168(1):17–33.

Goldstein EB, de Anda AY, Henry LM, Parker BJ. Variation in density, immune gene suppression, and coinfection outcomes among strains of the aphid endosymbiont Regiella insecticola. Evolution. 2023;77(7):1704–11.

Henry LM, Maiden MCJ, Ferrari J, Godfray HCJ. Insect life history and the evolution of bacterial mutualism. Ecol Lett. 2015;18(6):516–25.

Schmieder R, Lim YW, Edwards R. Identification and removal of ribosomal RNA sequences from metatranscriptomes. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(3):433–5.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(21):7188–96.

Kalantar KL, Carvalho T, de Bourcy CFA, Dimitrov B, Dingle G, Egger R, et al. IDseq—an open source cloud-based pipeline and analysis service for metagenomic pathogen detection and monitoring. GigaScience. 2020;9(10):giaa111.

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2012;29(1):15–21.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20.

Ruby JG, Bellare P, Derisi JL. PRICE: software for the targeted assembly of components of (Meta) genomic sequence data. G3 (Bethesda). 2013;3(5):865–80.

Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094–100.

Buchfink B, Reuter K, Drost HG. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2021;18(4):366–8.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Bohl JA, Lay S, Chea S, Ahyong V, Parker DM, Gallagher S, et al. Discovering disease-causing pathogens in resource-scarce Southeast Asia using a global metagenomic pathogen monitoring system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(11):e2115285119.

Batson J, Dudas G, Haas-Stapleton E, Kistler AL, Li LM, Logan P, et al. Single mosquito metatranscriptomics identifies vectors, emerging pathogens and reservoirs in one assay. eLife. 2021;10:e68353.

Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011;17(1):3.

Grubaugh ND, Gangavarapu K, Quick J, Matteson NL, De Jesus JG, Main BJ, et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):8.

Andrews S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data [Online]. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/2010.

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–52.

Wheeler TJ, Eddy SR. nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(19):2487–9.

Steinegger M, Söding J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(11):1026–8.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–402.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9.

Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):722–36.

Roach MJ, Schmidt SA, Borneman AR. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19(1):460.

Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112963.

Challis R, Richards E, Rajan J, Cochrane G, Blaxter M. BlobToolKit – Interactive quality assessment of genome assemblies. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020;10(4):1361–74.

Sayers EW, Bolton EE, Brister JR, Canese K, Chan J, Comeau DC, et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D20–6.

Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Simão FA, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(10):4647–54.

Levy Karin E, Mirdita M, Söding J. MetaEuk—sensitive, high-throughput gene discovery, and annotation for large-scale eukaryotic metagenomics. Microbiome. 2020;8(1):48.

Clarke HV. Genotypic and endosymbiont-mediated variation in parasitoid susceptibility and other fitness traits of the potato aphid, Macrosiphum euphorbiae. Doctoral Thesis. University of Dundee; 2013.

Turner D, Ackermann HW, Kropinski AM, Lavigne R, Sutton JM, Reynolds DM. Comparative analysis of 37 acinetobacter bacteriophages. Viruses. 2017;10(1):5.

Blitvich BJ, Firth AE. Insect-specific Flaviviruses: a systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses. 2015;7(4):1927–59.

Mazeaud C, Freppel W, Chatel-Chaix L. The multiples fates of the Flavivirus RNA genome during pathogenesis. Front Gen. 2018;9:595.

François S, Filloux D, Roumagnac P, Bigot D, Gayral P, Martin DP, et al. Discovery of parvovirus-related sequences in an unexpected broad range of animals. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):30880.

Wenger JA, Cassone BJ, Legeai F, Johnston JS, Bansal R, Yates AD, et al. Whole genome sequence of the soybean aphid, aphis glycines. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;123:102917.

Consortium IAG. Genome sequence of the pea aphid acyrthosiphon pisum. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(2):e1000313.

Horst AM, Nigg JC, Dekker FM, Falk BW. Endogenous viral elements are widespread in Arthropod genomes and commonly give rise to PIWI-interacting RNAs. J Virol. 2019;93(6):e02124–e2218.

Ryabov EV, Keane G, Naish N, Evered C, Winstanley D. Densovirus induces winged morphs in asexual clones of the rosy apple aphid, dysaphis plantaginea. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(21):8465–70.

Nigg JC, Kuo YW, Falk BW. Endogenous viral element-derived piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are not required for production of ping-pong-dependent piRNAs from Diaphorina citri Densovirus. Bio. 2020;11(5):e02209.

Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Lipkin WI. Discovery and characterization of mammalian endogenous parvoviruses. J Virol. 2010;84(24):12628–35.

Liu H, Fu Y, Xie J, Cheng J, Ghabrial SA, Li G, et al. Widespread endogenization of densoviruses and parvoviruses in animal and human genomes. J Virol. 2011;85(19):9863–76.

Pinheiro PV, Wilson JR, Xu Y, Zheng Y, Rebelo AR, Fattah-Hosseini S, et al. Plant viruses transmitted in two different modes produce differing effects on small RNA-mediated processes in their aphid vector. Phytobiomes J. 2019;3(1):71–81.

Kuno G, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, Cropp CB. Phylogeny of the genus flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72(1):73–83.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Keertana Tallapragada, Georgina Aitolo, and Mariam Sirag for help with insect stock maintenance. The University of Tennessee Knoxville’s Office of Innovative Technologies provided access to the ISAAC-NG computational cluster.

Funding

This work was funded by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant IOS-2152954 to BJP and DEB-2305653 to PRL. BJP is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences, funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PRL and BJP conceived the project. PRL and BJP wrote the manuscript. PRL, WB, SK, and BJP carried out the data curation, bioinformatic analysis, and software validation. PRL, WB, and MMM carried out the molecular work. PRL and BJP contributed to funding acquisition. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: S1 Table.

RNAseq reads report.

Additional file 2: S2 Table.

Parvoviridae reference database.

Additional file 3: S3 Table.

Metadata of the field-collected aphids screened for the Hamilltonella defensa bacterial symbiont.

Additional file 4: S4 Table.

Expressed Ambidensoviral EVEs from M. euforbiae genome (SRR23851809).

Additional file 5: S5 Table.

Quantitative metric in the heatmaps (data showed as reads per million aligning to the nucleotide database (NT rPM).

Additional file 6: S1 Figure.

MeV-1 consensus genome coverage breadth and depth in comparison to the reference genome (KT309079.1).

Additional file 7: S1 File.

Sequences of Trinity contigs flagged as Ambidensovirus sequences by TRAVIS.

Additional file 8: S2 File.

Sequences of contigs flagged as Flavivirus and Ambidensovirus sequences by CZID.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rozo-Lopez, P., Brewer, W., Käfer, S. et al. Untangling an insect’s virome from its endogenous viral elements. BMC Genomics 24, 636 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09737-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-023-09737-z