Abstract

Background

Lactobacillus gasseri as a probiotic has history of safe consumption is prevalent in infants and adults gut microbiota to maintain gut homeostasis.

Results

In this study, to explore the genomic diversity and mine potential probiotic characteristics of L. gasseri, 92 strains of L. gasseri were isolated from Chinese human feces and identified based on 16 s rDNA sequencing, after draft genomes sequencing, further average nucleotide identity (ANI) value and phylogenetic analysis reclassified them as L. paragasseri (n = 79) and L. gasseri (n = 13), respectively. Their pan/core-genomes were determined, revealing that L. paragasseri had an open pan-genome. Comparative analysis was carried out to identify genetic features, and the results indicated that 39 strains of L. paragasseri harboured Type II-A CRISPR-Cas system while 12 strains of L. gasseri contained Type I-E and II-A CRISPR-Cas systems. Bacteriocin operons and the number of carbohydrate-active enzymes were significantly different between the two species.

Conclusions

This is the first time to study pan/core-genome of L. gasseri and L. paragasseri, and compare their genetic diversity, and all the results provided better understating on genetics of the two species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lactobacillus gasseri, as one of the autochthonous microorganism colonizes the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and vagina of humans, has a variety of probiotic properties [1]. Clinical trials indicated that L. gasseri maintains gut and vaginal homeostasis, mitigates Helicobacter pylori infection [2] and inhibits some virus infection [3], which involve multifaceted mechanisms such as production of lactic acid, bacteriocin and hydrogen peroxide [4], degradation of oxalate [5], protection of epithelium invasion by pathogens exclusion [6].

Initially, it was difficult to distinguish L. gasseri, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus johnsonii, and later L. gasseri was reclassified as a separate species by DNA-DNA hybridization techniques [7], 16S rDNA sequencing [8] and repetitive element-PCR (Rep-PCR) [9] from the close related species. Sequencing technologies and whole-genome-based analysis made the clarification of taxonomical adjunct species more accurate [10, 11]. Nevertheless, no further investigation was performed on its subspecies or other adjunct species in recent years. ANI values were considered as a useful approach to evaluate the genetic distance, based on genomes [12, 13]. The ANI values were higher than 62% within a genus, while more than 95% of ANI values was recommended as the delimitation criterion for same species [14]. Seventy-five L. gasseri strains with publically available genomes were divided into two intraspecific groups by ANI at the threshold of 94% [15], subsequently some strains were re-classified as a new group, L. paragasseri, based on whole-genome analysis [16].

Sequencing technologies and bioinformatics analysis provide the opportunities to analyse more information of microbial species. Pan-genome is a collection of multiple genomes, including core genome and variable genome. The core genome consists of genes presented in all strains and is generally associated with biological functions and major phenotypic characteristics, reflecting the stability of the species. And variable genome consists of genes that exist only in a single strain or a portion of strains, and is generally related to adaptation to particular environments or to unique biological characteristics, reflecting the characteristics of the species [17]. Pan-genomes of other Lactobacillus species [18], such as Lactobacillus reuteri [19], Lactobacillus paracasei [20], Lactobacillus casei [21] and Lactobacillus salivarius [22] have previously been characterized. The genetic knowledge and diversity of L. gasseri and L. paragasseri is still in its infancy. In addition, previous in silico surveys have reported that Lactobacilli harbour diverse and active CRISPR-Cas systems, which has 6-fold-rate occurrence of CRISPR-Cas systems compared with other bacteria [23]. It is necessary to study CRISPR-Cas system to understand the adaptive immune system that protect Lactobacillus from phages and other invasive mobile genetic elements in engineering food microbes, and explore powerful genome engineering tool. Moreover, numerous bacteriocins were isolated from Lactobacillus genus, and these antimicrobials received increased attention as potential alternatives to inhibit spoilage and pathogenic bacteria [24]. A variety of strategies identify bacteriocin culture-based and in silico-based approaches, and to date, bacteriocin screening by in silico-based approaches have been reported in many research investigations [25].

In the current work, strains were isolated from fecal samples collected from different regions in China, and initially identified as L. gasseri by 16S rDNA sequencing. For further investigation, draft genomes of all the strains were sequenced by next generation sequencing (NGS) platform and analysed by bioinformatics to explore the genetic diversity, including subspecies/adjunct species, pan-genome, CRISPR-Cas systems, bacteriocin and carbohydrate utilization enzymes.

Results

Strains and sequencing

Based on 16S rDNA sequencing, 92 L. gasseri strains were isolated from fecal samples obtained from adults and children from different regions in China, with 66 strains being obtained from adults and 26 from children (47 strains were isolated from females, 45 were isolated from males) (Table 1). The draft genomes of all strains were sequenced using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology and strains were sequenced to a coverage depth no less than the genome 100 ×, and using the genome of L. gasseri ATCC33323 and L. paragasseri K7 as reference sequences.

ANI values

ANI values calculation of Z92 draft genomes was carried out through pairwise comparison at the 95% threshold to further identify their species (Fig. 1). All of the 94 strains were classified into two groups, with 80 strains including L. paragasseri K7 (as type L. paragasseri strain) showing an ANI value range 97–99%, and the other group consisted of 14 strains including the type strain L. gasseri ATCC 33323 (as type L. gasseri strain) with an ANI range 93–94% compared with L. paragasseri. According to a previous report, L. gasseri K7 was reclassified as L. paragasseri based on whole-genome analyses [16], therefore, other 79 strains on the same group with L. paragasseri K7 were preliminarily identified as L. paragasseri, while the remained 13 strains on the other branch with L. gasseri ATCC33323 were identified as L. gasseri.

Phylogenetic analysis

To further verify the results from ANI and evaluate the genetic distance among strains, the phylogenetic relationships between L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were investigated. OrthoMCL was used to cluster orthologous genes and 1282 orthologues proteins were shared by all the 94 genomes. A robust phylogenetic tree based on 1282 orthologues proteins was constructed (Fig. 2). The results indicated that all the 94 strains could be positioned on two branches, in which 80 strains were on the same cluster with L. paragasseri K7 and the other 14 strains were on the cluster with L. gasseri ATCC33323. Surprisingly, all the strains on the cluster with L. gasseri or L. paragasseri were completely consistent with the results from ANI analysis. Therefore, it was confirmed that division of 92 strains isolated from Chinese subjects into two subgroups; 79 strains belong to L. paragasseri, and 13 strains to L. gasseri, is correct. The strains were randomly selected from the fecal samples, suggesting that L. gasseri and L. paragasseri had no preference to either male or female subjects nor region and age. Moreover, the house-keeping genes pheS and groEL were extracted from the genomes and neighbor-joining trees were built. The tree showed that 13 strains of L. gasseri were clustered in a single clade (Fig. 3), which was consistent with phylogenetic data based on orthologous genes. However, there were many branches in the L. paragasseri groups, which indicated a high intraspecies diversity among L. paragasseri and needs further investigation (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

The phylogenetic tree based on orthologous genes. The red area was the L. gasseri cluster and the blue area was the L. paragasseri cluster. The purple circle indicated the strains isolated from infant feces and the gray indicated strains isolated from adults. The pink indicated strains from female and the green represent strains from male subjects

General genome features and annotation

The general information of the 80 genomes of L. paragasseri strains and 14 genomes of L .gasseri strains are summarized in Table 1. The sequence length of L. paragasseri ranged from 1.87 to 2.14 Mb, with a mean size of 1.97 Mb, and all 14 L. gasseri genomes had an average sequence length of 1.94 Mb with a range of 1.87–2.01 Mb. The L. paragasseri genomes displayed an average G + C content of 34.9% and L. gasseri genomes had an average G + C content of 34.82%. A comparable number of predicted Open Reading Frames (ORF) was obtained for each L. paragasseri genome that ranged from 1814 to 2206 with an average number of 1942 ORFs per genome, while L. gasseri had an average number of 1881 ORFs per genome. To further determine the function of each gene, non-redundant protein databases based on NCBI database were created, which revealed that average 84% of L. paragasseri ORFs were identified, while the remaining 16% were predicted to encode hypothetical proteins. Similarly, approximately 85% of L. gasseri ORFs were identified, while 15% were predicted to encode hypothetical proteins. The preference of the two species codons for the start codon were predicted, and the results showed that ATG, TTG and CTG in L. paragasseri with a calculated frequency percentage of 82.6, 10.3 and 7.1%, respectively, and 81.0, 11.7 and 7.4% in L. gasseri, respectively, suggesting that L. paragasseri and L. gasseri had a preference of using ATG as start codon [16].

To further analyse the genome-encoded functional proteins, the COG classification was performed for each draft genome. According to the results of the COG annotation, the genes were divided into 20 groups, and the details are shown in (Additional file 1: Table S1) and (Additional file 2: Table S2). The results revealed that carbohydrate transport and metabolism, defense mechanisms differed in different genomes of L. paragasseri, while L. gasseri showed only difference in defense mechanisms. Notably, due to draft genomes, the possibility of error from missing genes or incorrect copy number is significantly higher [28].

Pan/core-genome analysis

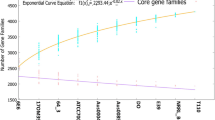

To analyze the overall approximation of the gene repertoire for L. paragasseri and L. gasseri in the human intestine, the pan-genomes of L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were investigated, respectively. The results showed that the pan-genome size of all 80 strains of L. paragasseri amounted to 6535 genes while the pan-genome asymptotic curve had not reached a plateau (Fig. 4), suggesting that when more L. paragasseri genomes were considered for the number of novel genes, the pan-genome would continuously increase. Meanwhile, the exponential value of deduced mathematical function is > 0.5 (Fig. 4), these findings indicated an open pan-genome occurrence within the L. paragasseri species. L. paragasseri had a supragenome about 3.3 times larger than the average genome of each strain, indicating L. paragasseri constantly acquired new genes to adapt to the environment during evolution. The pan-genome size of the 14 strains of L. gasseri was 2834 genes, and the exponential value of deduced mathematical function is < 0.5, thus it could not be concluded whether its pan-genome was open or not.

The number of conserved gene families constituting the core genome decreased slightly, and the extrapolation of the curve indicated that the core genome reached a minimum of 1256 genes in L. paragasseri and 1375 genes in L. gasseri, and the curve of L. paragasseri remained relatively constant, even as more genomes were added. The Venn diagram represented the unique and orthologues genes among the 80 L. paragasseri strains. The unique orthologous clusters ranged from 3 to 95 genes for L. paragasseri and ranged from 8 to 125 genes for L. gasseri (Fig. 5). As expected, the core genome included a large number of genes for translation, ribosomal structure, biogenesis and carbohydrate transport and metabolism, in addition to a large number of genes with unknown function (Additional file 5: Figure S1).

Identification and characterization of CRISPR in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri

The CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity system provided resistance against invasive bacteriophage or plasmid DNA such as some lytic bacteriophages in engineering food microbes, which consists of CRISPR adjacent to Cas genes. The presence of Cas1 proteins was used to determine the presence or absence of CRISPR-Cas systems, and Cas1 was found among the 39 strains of L. paragasseri, and 13 strains of L. gasseri. The occurrence of Cas1 genes in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri showed differences, in that 12 strains of L. gasseri consisted of two Cas1 genes, and the second Cas1 gene was located in a different region constituting a second putative CRISPR locus. Meanwhile, Cas2 and Cas9 were widespread across the two species, while Cas3, Cas5, Cas6 and Cas7 only occurred in L. gasseri. According to previous method of classification of the CRISPR subtypes, 52 Type II-A systems were detected in all the strains of L. gasseri and 39 strains of L. paragasseri, whereas the Type I-E system only occurred in 12 strains of L. gasseri except FHNFQ57-L4, indicating that subtype II-A was the most prevalence both in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri.

The phylogenetic analyses performed with Cas1, Cas2 and Cas9 from the two species showed L. paragasseri was clearly distinct from L. gasseri (Fig. 6). Strikingly, phylogenetic tree based on Cas1 and Cas2 proteins revealed that clusters consisted of only the second Cas1 and Cas2 proteins in Type I-E systems in L. gasseri, and the Cas1 and Cas2 proteins in subtype II-A systems in both L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were clustered in two groups. From this perspective, CRISPR-Cas could be used as an indicator to distinguish L. paragasseri and L. gasseri. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis of Cas9 indicated that the cluster was consistent with Cas1 and Cas2, indicating that co-evolutionary trends happened in CRISPR systems.

CRISPR-cas phylogenetic analyses for L. paragasseri and L. gasseri. a Phylogenetic tree based on the Ca1 protein, b Phylogenetic tree based on the Cas2 protein, c Phylogenetic tree based on the Cas9 protein. The CRISPR-Cas subtypes and bacterial species were written on the right and each group was colored

The features of all 60 CRISPR loci identified in L. paragasseri and L. gaseseri genomes are summarized in Table S3. The length of DRs were 36 nucleotides (nt) in 36 strains of L. paragasseri except FJSCZD2-L1, FHNFQ53-L2 and FHNXY18-L3, which had DR sequences with 26 nt. The 5′-terminal portion of DRs in L. paragasseri were composed of G (T/C) TTT and the DRs were weakly palindromic. The putative RNA secondary structure of the DRs in L. paragasseri contained two small loops (Fig. 7). The DRs of L. paragasseri shared two variable nucleotides at the 2nd and 29th site (C/T), and the difference affected the RNA secondary structures (Fig. 7). While two CRISPR loci in L. gasseri had different DR sequences and varied in length and content, in which most of them were 28 nt whereas L. gasseri FHNFQ56-L1 and FHNFQ57-L4 had a same DR as L. pargasseri (Additional file 3: Table S3). Further, spacer contents were uncovered for L. paragasseri and L. gaseseri, ranging from 3 to 22 CRISPR spacers (Additional file 3: Table S3). The number of spacers in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were variable and it provided information about the immunity record.

Features of DR sequences of CRISPR loci in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri. a The sequence of consensus DR sequences within L. paragasseri. b The sequence of consensus DR sequences in L. gasseri strains. The height of the letters indicates the frequency of the corresponding base at that position. c–e Predicted RNA secondary structures of CRISPR DR in L. paragasseri. f–g Predicted RNA secondary structures of the CRISPR DR in L. gasseri

Distribution of Bacteriocin operons

Identifying bacteriocins in vitro can be a challenging task, however, in silico analysis of genomes for presence of bacteriocin operons could make screening bacteriocin efficient. BAGEL was used to identify the potential bacteriocin operons in the current study. Three hundred twenty-three putative class II bacteriocin and 91 putative class Bacteriolysin (formerly Class III Bacteriocins) operons were identified in all 92 genomes (Additional file 4: Table S4). Class II bacteriocins are small heat stable peptides further subdivided IIa, IIb, IIc and IId based on the structure and activity of the peptides [25]. L. paragassseri genomes contained various bacteriocins including Class IIa (pediocin), Class IIb (gassericin K7B and gassericin T), Class IIc (acidocin B and gassericin A), Class IId (bacteriocin-LS2chaina and bacteriocin-LS2chainb), and Bacteriolysin, whereas all the strains of L. gasseri only encoded bacteriocin-helveticin-J (Bacteriolysin) except L. gasseri FHNFQ57-L4, which contained both bacteriocin-helveticin-J and pediocin operons.

Interestingly, gassericin K7B and gassericin T operons co-occured in 43 strains of L. paragasseri, and bacteriocin-LS2chaina and bacteriocin-LS2chainb co-occured in 67 strains of L. paragasseri. Sixteen gassericin A, 31 acidocin B, 69 pediocin and 78 bacteriocin-helveticin-J operons were also predicted in L. paragasseri indicating that helveticin homolog operons were more frequent than other operons. In addition, only one enterolysin A operon was found in L. paragasseri FHNFQ29-L2, FGSYC41-L1 and L. paragasseri FJSWX6-L7 contained a helveticin J operon.

Furthermore, according to the results, among all the 79 strains of L. paragasseri, at least one bacteriocin operon was found, in which 14 strains consisted of 8 bacteriocin operons including all types of Class II bacteriocin and bacteriocin-helveticin-J, and 17 strains contained 4 bacteriocin operons (pediocin, bacteriocin-LS2chaina, bacteriocin-LS2chainb and bacteriocin-helveticin-J), while L. paragasseri FHNFQ62-L6 was only predicted with bacteriocin-helveticin-J operon.

The glycobiome of L. paragasseri and L. gasseri

The earliest classifications of lactobacilli were based on their carbohydrate utilization patterns. In the current study, carbohydrate-active enzymes were analyzed by HMMER-3.1 and identified through carbohydrate-active enzyme (Cazy) database. Nineteen glycosyl hydrolase (GH) families, 7 glycosyl transferase (GT) families and 5 carbohydrate esterase (CE) families were predicted for each genome, and the distribution and abundance of GH, GT, CE family genes across the L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were showed by heatmap (Fig. 8).

The number of GH, GT and CE families’ enzymes were highly consistent in 12 strains of L. gasseri while variation was found in L. paragasseri. Among L. paragasseri, GH137 (β-L-arabinofuranosidase) was only predicted in 5 strains, GH65, GH73, GH8, CE9 and GT51 families showed exactly same and CE12 was detected in most of the strains except L. paragasseri FHNXY26-L3 and L. paragasseri FNMGHLBE17-L3. Notably, 12 strains of L. paragasseri including FNMGHHHT1-L5, FAHFY1-L2, FHNFQ25-L3, FHNXY18-L2, FHNXY26-L3, FHuNCS1-L1, FJXPY26-L4, FGSYC15-L1, FGSYC19-L1, FHLJDQ3-L5, FHNFQ3-L8 and FHNFQ53-L2, in which GH2 were absent, clustered a small branch in orthologous phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). Similarly, the strains of FJSWX21-L2, FAHFY7-L4, FGSYC7-L1, FGSYC43-L1, FGSYC79-L2, FGSZY12-L1, FGSZY27-L1, FGSZY29-L8, FHNXY6-L2, FHNXY12-L2, FHNXY29-L1, FGSZY30-L1, FHNXY44-L1 and FGSZY36-L1, in which GH78 were absent, also formed a single clade. The number of GH, GT and CE families’ enzymes from Zhangye (Gansu Province) were completely consistent.

Twelve strains of L. gasseri formed a single clade using hierarchical clustering method (Fig. 8). Both species of L. gasseri and L. paragasseri appeared to contain a consistent GH65, GH73 and GT51 (murein polymerase) families, while GH42 family (β-galactosidase and α-L-arabinopyranosidase) was only found in L. paragasseri. Additionally, the gene number of GT8 (α-transferase) family in L. gasseri was less than that in L. paragasseri. The results revealed that carbohydrate utilization patterns of L. gasseri differed from L. paragasseri. Carbohydrate-active enzymes abundance in L. paragasseri showed high diversity, but the difference was not a result of gender and age difference, and may be associated with diet habits of the host individual. Diversity do not correlate with gender and age and could be result of sugar diet habits of the host individual.

Discussion

NGS technologies have made sequencing easier to get high-quality bacterial genomes, and provides the possibility to better understand the genomic diversity within some genus [29]. In this study, genome sequences for 92 strains from human feces, which were preliminary identified as L. gasseri by 16S rDNA sequencing, combined with two publicly available genomes L. gasseri ATCC33323 and L. paragasseri K7, were further analysed. ANI values of 94 draft genomes were calculated through pairwise comparison at the 95% threshold, together with phylogenetic analysis based on orthologous genes and house-keeping genes (pheS and groEL) were performed to ensure the species affiliations and eliminated the mislabeled genomes only using ANI [30]. Seventy-nine strains were determined as L. paragasseri, and the remained 13 (14%) strains were L. gasseri, revealing that the most (86%) of isolates initially identified as L. gasseri by 16S rDNA sequencing were L. paragasseri. The current results were highly in line with previous publication by Tanizawa and colleagues [16], in which they reported that a large portion of genomes currently labelled as L. gasseri in the public database should be re-classified as L. paragasseri based on whole-genome sequence analyses as well. All those results indicated that L. gasseri and L. paragesseri are sister taxon with high similarity but not the same species, and the cultivable “L. gasseri” isolated from environment actually contained both L. gasseri and L. paragasseri species, which might be the reason for the high intraspecies diversity among “L. gasseri” exhibited. Meanwhile, groEL, a robust single-gene phylogenetic marker for Lactobacillus species identification [31], could serve as a marker to distinguish L. paragasseri and L. gasseri. Our current results provide a basis for distinguishing the two species by genotype. L. gasseri and L. paragasseri had no preference to colonize the female or male subjects, and the strains distribution had no trend on age neither infants nor adults. Nevertheless, a high intraspecies diversity in L. paragasseri may be caused by diet habits, health condition and others, which needs further research.

In general, the genome size of L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were smaller than other Lactobacillus species, which had an average size 1.96 Mb, while other Lactobacillus had a genome approximately 3.0 Mb, such as L. paracasei [20], L. casei [21], Lactobacillus rhamnosus [32]. Additionally, the G + C contents in L. paragasseri (34.9%) and L. gasseri (34.82%) were lower than that in other Lactobacillus species. For instance, average G + C contents were 38.96% in L. reuteri [19], 46.1–46.6% in L. casei, 46.5% in L. paracasei [20], and 46.5–46.8% in L. rhamnosus [33], and the average G + C content among lactobacilli genera is estimated at 42.4%. As previously found in bifidobacterial genomes, that the preferred start codon was ATG, also analysis of start codons in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri showed that they preferably used ATG as start codon [34].

Pan-genomes of L. paragasseri and L. gasseri were analysed, and the pan-genome size of the 80 strains among L. paragasseri and 14 strains of L. gasseri plus currently genome public strains of L. gasseri ATCC33323 and L. paragasseri K7 were 6535 and 2834 genes, respectively, and the core genomes were 1256 and 1375 genes, respectively, suggesting that open pan-genome within the L. paragasseri species and its pan-genome will increase if more L. paragasseri genomes were considered for the number of novel gene families and an open pan-genome implies that gene-exchanging within a species is higher [28]. But it could not conclude whether the pan-genome of L. gasseri was open or not because of limited number of sequenced genomes.

It has been reported that lactic acid bacteria are enriched resource for Type II CRISPR systems [35] and some previous studies on L. gasseri CRISPR-Cas reported that L. gassseri harboured type II-A CRISPR-Cas system with diversity in spacer content, and confirmed functionality [36]. However, the former results on “L. gasseri” might not be the real L. gasseri, as L. paragasseri was distinguished from L. gasseri recently, which might be mixed in the previous research. In the current result, L. gasseri and L. paragasseri were distinguished and separately, then were loaded for CRISAP-Cas analysis, respectively. The results showed that 39 of 79 L. paragasseri strains carried Type II systems and all the strains of L. gasseri harboured Type II and Type I CRISPR-Cas system (except FHNFQ57-L4), implying that both L. paragasseri and L. gasseri are main candidates for gene editing and cleavage of lytic bacteriophages in food industry. In the current study we found that Cas1, Cas2 and Cas9 were widespread across both L. paragasseri and L. gasseri species, and the L. gasseri species had a second Cas1 and Cas2, while the second Cas1 and Cas2 were clustered in a single clade through phylogenetic analyses. Similarity, the Cas9 gene was different between the two species, suggesting that CRISPR-Cas could provide a unique basis for resolution at the species-level [37], and the CRISPR-Cas systems may contribute to the evolutionary segregation [33].

It has been reported that L. gasseri produces variety of bacteriocin to inhibit some pathogens. Screening bacteriocin in vitro was complex and difficult while in silico analysis could make it rapid, generally using BAGEL to identify the potential bacteriocin operons. In the current study, most of the L. gasseri strains only had a single bacteriocin operon (Bacteriocin_helveticin_J), while L. paragasseri showed a variety of bacteriocin operons belonging to class II such as gassericin K7B, gassericin T and gassericin A. With the current results, although bacteriocin was not separated and verified in vitro, we presume that the strains with the high-yielding of bacteriocin, which was commonly known as L. gasseri, should actually be L. paragaseri rather than L. gasseri. For instance, previously L. gasseri LA39 was reported to produce gassericin A [38] and L. gasseri SBT2055 [39] could produce gassericin T, according to our results, they might belong to L. paragasseri species instead of L. gasseri. To confirm our hypothesis, more L. gasseri strains should be isolated and screened for bacteriocin to verify.

In order to investigate L. paragasseri and L. gasseri carbohydrate-utilization capabilities, carbohydrate-active enzymes were predicted for all the strains and these families have predicted substrates and functional properties for each strain. Analyzing the abundance of Cazy revealed that carbohydrate utilization patterns of L. gasseri significantly distinguished with L. paragasseri in genotype, which provided foundation for fermentation experiment with unique carbon sources. Moreover, 10.83% core genes had predicted function of carbohydrate transport and metabolism, which is the reason for strains diversity and separation.

Conclusion

Ninety two strains isolated from Chinese subjects were initially identified as L. gasseri by 16S rDNA sequencing, while based on whole-genome analyses they were reclassified. According to ANI values and phylogenetic analysis based on both orthologous genes and house-keeping genes, 13 strains and 79 strains were reclassified as L. gasseri and L. paragasseri, respectively, which revealed a new species-level taxa from Chinese subjects. Pan-genome structure for L. paragasseri was open, meanwhile, L. paragasseri had a supragenome about 3.3 times larger than the average genome size of individual strains. After species reclassification, genetic features CRISPR-Cas systems, bacteriocin, and carbohydrate-active enzymes were analysed, revealing differences in the genomic characteristics of L. paragasseri and L. gasseri strains isolated from human feces and mine potential probiotic characteristics in the two species. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate pan/core-genome of L. gasseri and L. paragasseri, compared the genetic features between the two species.

Methods

Isolation of strains, genome sequencing and data assembly

Ninety-two strains isolated from adult and infant feces from different regions in China were listed in Table 1. Strains were selected in Lactobacillus selective medium (LBS) [4] and incubated at 37 °C in an anaerobic atmosphere (10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2) in a anaerobic workstation (AW400TG, Electrotek Scientific Ltd., West Yorkshire, UK) for 18-24 h and 16S rRNA genes were sequenced for species identification. All the identified L. gasseri strains were stocked at -80 °C in 25% glycerol [40]. Draft genomes of all the 92 L. gasseri strains were sequenced via Illumina Hiseq× 10 platform (Majorbio BioTech Co, Shanghai, China), which generated 2 × 150 bp paired-end libraries and construct a paired-end library with an average read length of about 400 bp. It used double-end sequencing, which single-ended sequencing reads were 150 bp. The reads were assembled by SOAPde-novo and local inner gaps were filled by using the software GapCloser [41]. Two publicly available genomes (L. gasseri ATCC33323 [26] and L. gasseri K7 [27]) from National Centre for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were used for comparison and the latter one has recently been re-classified as L. paragasseri [16].

Average nucleotide identity (ANI) values

ANI between any two genomes was calculated using python script (https://github.com/widdowquinn/pyani) [42] and the resulting matrix was clustered and visualized using R packages heatmap software [43].

Phylogenetic analyses

All the genomic DNA were translated to protein sequences by EMBOSS-6.6.0 [44]. OrthoMCL1.4 was used to cluster orthologous genes and extracted all orthologous proteins sequences of 94 strains. All orthologous proteins were aligned using MAFFT-7.313 software [45] and phylogenetic trees were constructed using the python script (https://github.com/jvollme/fasta2phylip) and the supertree was modified using Evolgenius (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/). The house-keeping genes, pheS [46] and groEL [47], were extracted from the genomes using BLAST (Version 2.2.31+) [48], and the multiple alignments were carried out through Cluster-W (default parameters), and the single gene neighbor-joining trees were built by MEGA 6.0 [49], with bootstrap by a self-test of 1000 resampling.

General feature predictions and annotation

The G + C content and start codon of each genome were predicted with Glimmer 3.02 [50] (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/glimmer) prediction software. Transfer RNA (tRNA) was identified using tRNAscan-SE 2.0 [51] (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/). Open Reading Frame (ORF) prediction was performed with Glimmer3.02 and ORFs were annotated by BLASTP analysis against the non-redundant protein databases created by BLASTP based on NCBI. Functions of the genome-encoded proteins were categorized based on clusters of orthologous groups (COG) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/) assignments.

Pan/core-genome analysis

Pan-genome computation for L. paragasseri and L. gasseri genomes was performed using the PGAP-1.2.1, which analysed multiple genomes based on protein sequences, nucleotide sequences and annotation information, and performed the analysis according to the Heap’s law pan-genome model [17, 52]. The ORF content of each genome was organised in functional gene clusters via the Gene Family method and a pan-genome profile was then built.

CRISPR identification and characterization of isolated strains

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) regions and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins were identified by CRISPRCasFinder [53] (https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/CrisprCasFinder), and the CRISPR subtypes designation was based on the signature of Cas proteins [54]. MEGA6.0 was used to perform multiple sequence alignments, and neighbor-joining trees based on Cas1, Cas2 and Cas9 were bulit. The sequence of conserved direct repeats (DRs) were visualized by WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/). RNA secondary structure of DRs was performed by RNAfold web server with default arguments (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/).

Bacteriocin identification

The bacteriocin mining tool BAGEL3 was used to mine genomes for putative bacteriocin operons [55]. To determine the bacteriocins pre-identified by BAGEL3, BLASTP was secondly used to search each putative bacteriocin peptide against those pre-identified bacteriocins from BAGEL screening, and only the consistent results from both analysis were recognized as truly identified bacteriocin.

The L. gasseri glycobiome

Analysis of the families of carbohydrate-active enzymes was carried out by using HMMER-3.1 (http://hmmer.org/) and with below a threshold cutoff of 1e-05. The copy number of the verified enzymes were summarized in a heatmap with hierarchical clustering method and Pearson distance [35].

Availability of data and materials

The genome datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANI:

-

Average nucleotide identity

- BLAST:

-

Basic alignment search tool

- Cazy:

-

Carbohydrate-active enzyme

- CE:

-

Carbohydrate esterase

- COG:

-

Clusters of orthologous groups

- GH:

-

Glycosyl hydrolase

- GT:

-

Glycosyl transferase

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- nt:

-

Nucleotides

- ORF:

-

Open Reading Frames

- Rep-PCR:

-

Repetitive element-PCR

References

Selle K, Klaenhammer TR. Genomic and phenotypic evidence for probiotic influences of Lactobacillus gasseri on human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(6):915–35.

Ushiyama A, Tanaka K, Aiba Y, Shiba T, Takagi A, Mine T, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 as a probiotic in clarithromycin-resistant helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;18(8):986–91.

Harata G, He F, Hiruta N, Kawase M, Kubota A, Hiramatsu M, et al. Intranasally administered Lactobacillus gasseri TMC0356 protects mice from H1N1 influenza virus infection by stimulating respiratory immune responses. World J Microbiol Technol. 2011;27(2):411–6.

Strus M, Brzychczy-Włoch M, Gosiewski T, Kochan P, Heczko PB. The in vitro effect of hydrogen peroxide on vaginal microbial communities. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2013;48(1):56–63.

Lewanika TR, Reid SJ, Abratt VR, Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Lactobacillus gasseri gasser AM63(T) degrades oxalate in a multistage continuous culture simulator of the human colonic microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;61(1):110–20.

Luccia BD, Mazzoli A, Cancelliere R, Crescenzo R, Ferrandino I, Monaco A, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri SF1183 protects the intestinal epithelium and prevents colitis symptoms in vivo. J Funct Foods. 2018;42:195–202.

Lauer E, Kandler O. Lactobacillus gasseri sp. nov., a new species of the subgenus Thermobacterium. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie: I. Abt. Originale C: Allgemeine, angewandte und ökologische Mikrobiologie. 1980;1(1):75–8.

Kullen MJ, Sanozkydawes RB, Crowell DC, Klaenhammer TR. Use of the DNA sequence of variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene for rapid and accurate identification of bacteria in the Lactobacillus acidophilus complex. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;89(3):511–6.

Gevers D, Huys G, Swings J. Applicability of rep-PCR fingerprinting for identification of Lactobacillus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;205(1):31–6.

Casey G, Conti D, Haile R, Duggan D. Next generation sequencing and a new era of medicine. Gut. 2013;62(6):920–32.

Berger B, Pridmore RD, Barretto C, Delmasjulien F, Schreiber K, Arigoni F, et al. Similarity and differences in the Lactobacillus acidophilus group identified by polyphasic analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(4):1311–21.

Kim M, Oh HS, Park SC, Chun J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(Pt 2):346–51.

Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57(1):81–91.

Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2567–72.

Tada I, Tanizawa Y, Endo A, Tohno M, Arita M. Revealing the genomic differences between two subgroups in Lactobacillus gasseri. Biosci Microbiota Food Health. 2017;36(4):155–9.

Tanizawa Y, Tada I, Kobayashi H, Endo A, Maeno S, Toyoda A, et al. Lactobacillus paragasseri sp. nov., a sister taxon of Lactobacillus gasseri, based on whole-genome sequence analyses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:3512–7.

Zhao Y, Wu J, Yang J, Sun S, Xiao J, Yu J. PGAP: pan-genomes analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(3):416–8.

Inglin RC, Meile L, Stevens M. Clustering of pan- and core-genome of Lactobacillus provides novel evolutionary insights for differentiation. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):284.

Wegmann U, Mackenzie DA, Zheng J, Goesmann A, Roos S, Swarbreck D, et al. The pan-genome of Lactobacillus reuteri strains originating from the pig gastrointestinal tract. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):1023.

Smokvina T, Wels M, Polka J, Chervaux C, Brisse S, Boekhorst J, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei comparative genomics: towards species pan-genome definition and exploitation of diversity. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68731.

Broadbent JR, Neenoeckwall EC, Stahl B, Tandee K, Cai H, Morovic W, et al. Analysis of the Lactobacillus casei supragenome and its influence in species evolution and lifestyle adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1):533.

Harris H, Bourin M, Claesson MJ, O'Toole PW. Phylogenomics and comparative genomics of Lactobacillus salivarius, a mammalian gut commensal. Microbial Genomics. 2017;3(8):e000115.

Crawley AB, Henriksen ED, Stout E, Brandt K, Barrangou R. Characterizing the activity of abundant, diverse and active CRISPR-Cas systems in lactobacilli. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11544.

Piper C, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Discovery of medically significant lantibiotics. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2009;6(1):1–18.

Collins FWJ, O’Connor PM, O’Sullivan O, Gómezsala B, Rea MC, Hill C, et al. Bacteriocin gene-trait matching across the complete Lactobacillus pan-genome. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3481.

Makarova K, Slesarev A, Wolf Y, Sorokin A, Mirkin B, Koonin E, et al. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(42):15611–6.

Treven P, Trmčić A, Bogovič MB, Rogelj I. Improved draft genome sequence of probiotic strain Lactobacillus gasseri K7. Genome Announcement. 2014;2(4):e00725–14.

Kelleher P, Bottacini F, Mahony J, Kilcawley KN, van Sinderen D. Comparative and functional genomics of the Lactococcus lactis taxon; insights into evolution and niche adaptation. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):267.

Beedanagari S, John K. Next generation sequencing. Encyclopedia Toxicol. 2014;4:501–3.

Figueras MJ, Beazhidalgo R, Hossain MJ, Liles MR. Taxonomic affiliation of new genomes should be verified using average nucleotide identity and multilocus phylogenetic analysis. Genome Announcement. 2014;2(6):00927–14.

Yu C, Jin J, Meng LQ, Xia HH, Yuan HF, Wang J, et al. Sequence comparison of phoR, gyrB, groEL, and cheA genes as phylogenetic markers for distinguishing Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and B. subtilis and for identifying Bacillus strain B29. Cell Mol Biol. 2017;63(5):19–24.

Douillard FP, Ribbera A, Kant R, Pietilä TE, Järvinen HM, Messing M, et al. Comparative genomic and functional analysis of 100 Lactobacillus rhamnosus strains and their comparison with strain GG. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003683.

Ceapa C, Davids M, Ritari J, Lambert J, Wels M, Douillard FP, et al. The variable regions of Lactobacillus rhamnosus genomes reveal the dynamic evolution of metabolic and host-adaptation repertoires. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8(6):1889–905.

Bottacini F, O’Connell Motherway M, Kuczynski J, O’Connell KJ, Serafini F, Duranti S, et al. Comparative genomics of the Bifidobacterium breve taxon. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(1):170.

Sun Z, Harris HMB, Angela MC, Guo C, Silvia A, Zhang W, et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of Lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8322.

Sanozky-Dawes R, Selle K, O’Flaherty S, Klaenhammer T, Barrangou R. Occurrence and activity of a type II CRISPR-Cas system in Lactobacillus gasseri. Microbiology. 2015;161(9):1752–61.

Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Crawley AB, Sanchez B, Barrangou R. Characterization and exploitation of CRISPR loci in Bifidobacterium longum. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1851.

Kawai Y, Saito T, Toba T, Samant SK, Itoh T. Isolation and characterization of a highly hydrophobic new bacteriocin (gassericin a) from Lactobacillus gasseri LA39. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58(7):1218–21.

Kawai Y, Saitoh B, Takahashi O, Kitazawa H, Saito T, Nakajima H, et al. Primary amino acid and DNA sequences of gassericin T, a lactacin F-family bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64(10):2201–8.

Lähteinen T, Malinen E, Koort JMK, Mertaniemi-Hannus U, Hankimo T, Karikoski N, et al. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus isolates originating from porcine intestine and feces. Anaerobe. 2010;16(3):293–300.

Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-readde novoassembler. GigaScience. 2012;1(1):18.

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19126–31.

Kolde R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps. R package version 061; 2012.

Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16(6):276–7.

Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2017;30:3059.

Oren A, Garrity GM. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68(9):2707–9.

Shevtsov AB, Kushugulova AR, Tynybaeva IK, Kozhakhmetov SS, Abzhalelov AB, Momynaliev KT, et al. Identification of phenotypically and genotypically related Lactobacillus strains based on nucleotide sequence analysis of the groEL, rpoB, rplB, and 16S rRNA genes. Microbiologiia. 2011;80(5):659–68.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):421.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9.

Delcher A, Bratke K, Powers E, Salzberg S. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(6):673–9.

Lowe TM, Chan PP. tRNAscan-SE on-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W54–7.

Duranti S, Milani C, Lugli GA, Mancabelli L, Turroni F, Ferrario C, et al. Evaluation of genetic diversity among strains of the human gut commensal Bifidobacterium adolescentis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23971.

Couvin D, Bernheim A, Toffanonioche C, Touchon M, Michalik J, Néron B, et al. CRISPRCasFinder, an update of CRISRFinder, includes a portable version, enhanced performance and integrates search for Cas proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W246–51.

Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Fabrizio C, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(11):722–36.

van Heel AJ, de Jong A, Montalbán-López M, Kok J, Kuipers OP. BAGEL3: automated identification of genes encoding bacteriocins and (non-)bactericidal posttranslationally modified peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(W1):W448–53.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31530056, 31820103010, 31801521), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. JUSRP11733), National Firs-Class Discipline Program of Food Science and Technology (JUFSTR20180102) and the Jiangsu Province “Collaborative Innovation Center for Food Safety and Quality Control”. The funding body only provided research funds without any contribution in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was designed by XZ, BY, HZ and WC. The experiments were carried out by XZ. Data were analyzed by XZ, BY and JZ under WC supervision. The manuscript was written by XZ and BY, revised by XZ, BY, CS, PR, HZ and WC. All the authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Jiangnan University, China (SYXK 2012–0002). All the fecal samples from healthy persons were for public health purposes and these were the only human materials used in present study. Written informed consent for the use of their fecal samples were obtained from the participants or their legal guardians. All of them conducted health questionnaires before sampling and no human experiments were involved. The collection of fecal sample had no risk of predictable harm or discomfort to the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file1: Table S1.

Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COGs) classification of L. paragasseri

Additional file2: Table S2.

Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COGs) classification of L. gasseri

Additional file3: Table S3.

CRISPR-Cas systems in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri strains

Additional file4: Table S4.

Bacteriocin Operons in L. paragasseri and L. gasseri

Additional file5: Figure S1.

Functional assignment of the L. paragassei (a) and L. gasseri core genome based on the COG database

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Yang, B., Stanton, C. et al. Comparative analysis of Lactobacillus gasseri from Chinese subjects reveals a new species-level taxa. BMC Genomics 21, 119 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-6527-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-6527-y