Abstract

Background

Understanding the distribution pattern of species and their suitable habitat is key to focus conservation efforts. Climate change has had notable impact on the distribution and extent of suitable habitats, and the long-term survival of various species. We aim to determine the distribution and extent of suitable habitats for Tauraco ruspolii and T. leucotis in Ethiopia and predict their range in the 2050s and 2070s using MaxEnt algorithm. We used 25 and 29 rarified occurrence points for T. ruspolii and T. leucotis, respectively, and 13 environmental variables. Three regularization multipliers and two cut-off thresholds were used to map the potential suitable habitats for each species under current and future climates. Maps were assembled from these techniques to produce final composite tertiary maps and investigated the habitat suitability overlap between the two species using the UNION tool in the geographical information system.

Result

All model run performances were highly accurate for both species. Precipitation of the driest month and vegetation cover are the most influential variables for the habitat suitability of T. ruspolii. The habitat suitability of T. leucotis is also mainly influenced by mean temperature of the driest quarter and vegetation cover. Under the current climate, the suitable habitat predicted for T. ruspolii covered about 24,639.19 km2, but its range size change shows a gain and increase by 156.00% and 142.68% in 2050 and 2070, respectively. The T. leucotis‘s current suitable habitat ranges about 204,397.62 km², but this is reduced by 40.84% and 68.67% in 2050 and 2070, respectively. Our modeling also showed that there was suitable habitat overlap between them at the margin of their respective habitat types in time series.

Conclusion

We concluded that there is a direct or indirect impact of climate change on the suitable habitat range expansion for T. ruspolii and contraction for T. leucotis as well as overlapping of these turaco species in different regions of Ethiopia. Therefore, understanding the distribution of current and future suitable habitats of the two turaco species can provide valuable information to implement conservation practices for the species and the regions as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The distribution pattern of species and the availability of their suitable habitats were mainly affected by climate change which is driven by anthropogenic pressures at a global scale in the current Anthropocene Epoch [1,2,3,4]. Recently, there has been an increasing interest in modeling and mapping the habitat suitability of species including birds to prioritize conservation areas and predict the possible changes of their suitable habitats due to climate change [5,6,7,8].

Bird species, like other species, either adapt to the accelerating climate change, shift out of their natural range (i.e., loss or gain), or become extinct [5, 6, 8]. Shifting is usually altitudinal or latitudinal [9,10,11]. Restricted range birds are more vulnerable to extinction when they experience climate change due to loss of the suitable habitats [6, 12]. Globally, an increase of temperature by 1ºC is projected to have a non-linear increase in bird extinction by 100–500 species in future climatic conditions [6]. This is more severe for forest-specialist birds in the Afro-tropic biogeographic realm since they require specific ecological conditions [13]. For instance, several frugivores require tree holes and fleshy-fruited trees for reproduction and feeding, respectively [14, 15]. Turacos are among the Afro-tropical montane forest specialist birds and play critical ecological roles mainly as seed dispersers [14]. Due to the rapid loss of forest cover and other factors in Africa, several turaco species are at risk of population decline. Moreover, Tauraco ruspolii of the Ethiopian endemic turaco and T. bannermani of West Africa are considered globally threatened [16]. Particularly, Tauraco ruspolii is restricted in a narrow range in southern Ethiopia and vulnerable to habitat degradation, illegal tree cutting, competition, and hybridization with the least concern T. leucotis [17, 18].

Research on the impact of climate change on avian species in Africa particularly in Ethiopia is untouched except [10] on the Ethiopian bush crow (Zavattariornis stresemani) and white-tailed swallow (Hirundo megnensis) and [19] on four highland birds. With this study, we employed one of the Species Distribution Models (SDMs), Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt, ), to predict the distribution and extent of suitable habitats of T. ruspolii and T. leucotis [20] under changing climates in Ethiopia. This model is the most popular and robust even with small occurrence points [21]. Thus, we aimed to determine the distribution and extent of suitable habitats and their influential predictors for the two turaco species under the changing climatic conditions. Furthermore, the study was aimed to calculate the suitable habitats overlap between the two turaco species.

Materials and methods

Species occurrence data

The present study utilized the occurrence data of target species collected in Ethiopia (Fig. 1). Ethiopia is home to one of the richest and most unique assemblages of fauna and flora on the African continent [22]. In the country, about 863 bird species are believed to be recognized, of which 19 are endemic to the country alone and additionally 14 endemics shared with Eritrea [23]. The current studied turaco species are distributed in almost in common altitudinal range from 450 to 3600 m a. s. l [24].

We obtained 54 and 119 occurrence points for T. ruspolii and T. leucotis, respectively, from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org) and previous published literature [25,26,27,28]. These occurrence points were spatially rarified with 1 km² spatial resolution using SDM toolbox V2.5 [29] to avoid spatial autocorrelations [30]. Thus, the retained 25 and 29 occurrence points of T. ruspolii and T. leucotis, respectively, were used for building habitat suitability models of the target taxa (Fig. 1; Table S1).

Environmental variables

Habitat suitability of species and their spatial distribution depend on the cumulative interaction of various environmental variables [31]. In this study, 19 bioclimatic variables, topographic attributes, land use land covers as well as vegetation covers are considered.

The current bioclimatic data (i.e., an average of 1970 to 2000) were downloaded from WorldClim version 2.1 at a spatial resolution of 30s arc (1 km2) [32]. By assuming all current environmental variables will be unchanged, the future bioclimatic variables were also downloaded from the same source. The period of 2050s (2041–2060) and 2070s (2061–2080) with two shared socioeconomic pathways (i.e., the intermediate emission pathway-SSP4.5 and the worst-SSP8.5) developed by HadGEM2-Es global circulation models (GCMs) were used [32]. The topographic variables were derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Digital Elevation Model (SRTM-DEM) [33]. The Ethiopian vegetation types (http://landscapeportal.org/layers/geonode:veg.ethiopia) whereas land use land cover map was obtained from (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/) were also used. All of the environmental variables were processed using ArcGIS version 10.7 spatial analyst tools at 1 km2 resolution to have the same extent, projection and resolution [20].

To avoid multi-collinearity among environmental variables and increas model accuracy, we employed Pearson’s pair-wise correlation using DISMO package and then the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) using USDM package [34] using R v4.2.2. For this, we first stacked 24 environmental variables and extracted their values at each of the occurrence points and additionally at randomly generated 10, 000 pseudo-absence points [35]. As a threshold, we used a correlation coefficient |r| ≤ 0.70 [30)] and VIF ≤ 10, and finally, we retained 13 of the same environmental variables for both species’ distribution and habitat suitability modeling (Fig. S1; Table 1).

Model setting and prediction

For both studied species, we used a similar model setting in Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt Version 3.4.4) [20]. The model also iterated 5000 times with 10 replications and used a default cross-validation run type. Regularization multiplier was set in three complex levels (labeled as 1Reg, 5Reg, and 8Reg) [36, 37]. The remaining settings were left as default. The predictive performance of the model was assessed using the Area Under Curve (AUC) of the Receiving Operator Characteristics (ROC) curve which provides a threshold-independent overall accuracy ranging between 0.5 and 1.0 [20]. Thus, models with AUC > 0.90 is considered to be high accuracy, 0.70 < AUC < 0.90 is good, 0.50 < AUC < 0.70 low accuracy and AUC ≤ 0.50 no better than randomness [38, 39].

We used two thresholds to classify the MaxEnt output maps into binary suitable / unsuitable: (1)10 Percentile Training Presence logistic threshold (10PTP) and (2) Maximum Test Sensitivity plus Specificity logistic threshold (MTSS). 10TP is explained as the predicted probability at 10% omission rate of the training data while MTSS is the probability of threshold at which the sum of fractions of correctly predicted presence and pseudo-absence points is the highest [40]. As a result, a total of six current binary maps (three regularization multiplier times two thresholds) and 24 binary maps for future projection (two future periods times two scenario times three regularization multiplier times two thresholds) were produced per species. Then, we applied ensemble approach for these binary maps and reclassified them into three habitat suitability classes based on agreements among the pixels [41; 42]: (1), pixels from less than 30% binary maps ( only one map for the current and up to three maps for each future projection period ) were considered as unsuitable; (2) between 30% and 60% binary maps (up to three for current and up to seven maps for each future projection period) were assumed to be uncertain and (3) above 60% (up to six for current and up to twelve for each future projection period) were considered to be suitable with high certainty.

Finally, species range size change between current prediction and each future projection period was employed to detect spatiotemporal change in habitat suitability for each species using the ArcMap version 10.7. Species range size change includes remain suitable, remain unsuitable, loss, gain, current range size, future range size and net species range size change. We also used UNION tool of the ArcMap to detect suitable habitat overlap between the two species [43]. The UNION tool provided three types of polygons: (1) the area of the polygons which has only T. ruspolii represent, (2) polygon which represents only the areas where T. leucotis present, (3) combined polygon which represents the areas of overlap for the two species. Then, we calculated the areas of these polygons and the area percentage of T. ruspolii with the suitable range of the T. leucotis and vice versa using the formula:

Results

Variable importance and model performance

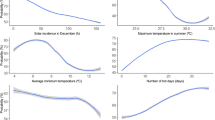

The average percent contribution of variables indicated that precipitation of the driest month (Biol14 = 28.9%), temperature seasonality (Biol4 = 28.4%), vegetation cover (20.8%), and precipitation of the warmest quarter (Biol18 = 10.8%) are the most determinant environmental variables for the habitat suitability prediction of T. ruspolii (Table 1). As the response curves revealed, T. ruspolii preferred habitats with Biol14 range from 10 to 20 mm (Fig. S2a). Its high habitat suitability (0.8) was also observed when the Biol4 (standard deviation x100) ranged from 50-100oC (Fig. S2b). During the warmest quarter, its habitat suitability increases until the precipitation (Biol18) reaches 300 mm then becomes stable (Fig. S2c). Desert and semi-desert scrubland, dry evergreen Afro-montane Forest and Combretum-Terminalia woodland are also the most preferable vegetation covers for this species.

On the other hand, the habitat suitability of T. leucotis is mainly influenced by the mean temperature of driest quarter (Biol9 = 39.77%), vegetation cover (27.27%) and land use land cover (23.17%) (Table 1). The non-linear response curve in (Fig. S3a) depicted that the habitat suitability of T. leucotis is negatively correlated with the mean temperature of the driest quarter (Biol9). Its most preferred vegetation cover is wide and ranges from Afro-alpine vegetation to Combretum-Terminalia woodland.

The AUC values of training and test datasets of the studied species are almost similar in the corresponding regularization multipliers. Since the AUC values of T. ruspolii are > 0.90, its model performance is found in high accuracy in all regularization multipliers and datasets (Table 2). The model also showed high performance accuracy for T. leucotis with the exception on the test dataset at 8Reg which failed with good accuracy (Table 2). The relation of regularizations and binary map thresholds indicated that the extent of predicted suitable habitat is reduced as regularization multipliers increase (i.e., model complexity decreases) in all thresholds for both species (Table 2). This implies that wide suitable habitat resulted in higher model complexity (1Reg) than at lower complexity (8Reg) regularization multiplier.

Current and future habitat suitability

The current predicted suitable habitat of T. ruspolii is mainly found in southern Ethiopia (relatively large extent), southwestern and northwestern Ethiopia (Fig. 2). Assembling of the future projection of T. ruspolii showed suitable habitat expansion with high certainty in both future periods (more pronounced in 2050) (Table 3). It is also more observed at southern Ethiopia.

Intersect of current with future climatic conditions indicated that T. ruspolii gain more than its current suitable habitat range (more than 100%) in both projected future periods (Table 3). Thus, the net habitat suitability change showed positive across the time series.

Our model prediction has shown that T. leucotis has wide habitat suitability and distribution range relative to T. ruspolii under current and future climate conditions. The current predicted suitable habitat of T. leucotis is extended mainly from central Ethiopia towards south, southeastern, southwestern and northwestern Ethiopia with localities dominated by Afro-montane vegetation, dry evergreen forest, and Acacia-Commiphora woodland of the Rift Valley and Combretum-Terminalia woodland (Fig. 3).

Unlike T. ruspolii, assembling the future projection of T. leucotis showed a reduction of suitable habitat range relative to the current climatic condition (Table 3). However, it would be still higher than the projection of T. ruspolii. The intersection of current with future climatic conditions also revealed this reality by showing a negative net change. T. leucotis lost more than 30.00% of its current suitable habitat range but gained less than 1.00% in both projection future periods (Table 3). The majority of its suitable habitats, particularly, in central Rift Valley, in Hararge highlands, and around Lake Tana are expected to be lost (Fig. 4).

Intersect of the current tertiary maps with future climate conditions that showing projected habitat suitability change from current to future. The first row indicated the intersection of current with 2050s and 2070s of T. ruspolii whereas the second row indicated the intersection of current with 2050s and 2070s of T. leucotis

Suitable habitat overlaps between species

Habitat suitability overlap between T. ruspolii and T. leucotis is observed in the projection periods with a slight shifting. It is found at the habitat margin of the respective species mainly in southern Ethiopia, northwestern Ethiopia (particularly, in Awi and East Gojjam), Western Ethiopia (East Wollega) and southeastern Ethiopia (Bale and Arsi areas) (Fig. 5).

Minimum habitat suitability overlaps between T. ruspolii and T. leucotis is observed in the 2070s whereas its maximum overlap is observed in 2050 (Table 4). As a general trend, the area percentage of T. ruspolii that overlaps with the range of T. leucotis is larger than the area percentage of T. leucotis that overlaps with the range of T. ruspolii in all periods (Table 4). However, a larger difference in area percentage overlap between these two species is observed in the current climate condition (15.89%).

Discussion

Variable importance and model evaluation

Species Distribution Models are the most popular technique for assisting the management of specific species. The models may be constructed using various algorithms, predictors, and numbers of response variables and the confidence of their results depend on the goal and accuracy of the response variables. Among the bioclimatic variables, the model predicted that precipitation of the driest month (Biol14) and the warmest quarter (Biol18) affected the habitat suitability of T. ruspolii. This is because precipitation is linked to the richness of plant species and their primary productivity, thereby providing habitat requirements for their survival and success of reproduction [44]. For instance, Gwitira et al. [45] revealed that plant species richness increased as the precipitation of the warmest quarter increased up to 450 mm (which is not far from the result of this study i.e., 300 mm) in Southern Africa Savannah. Low precipitation in lowland areas is also a factor for the altitudinal shifting of lowland tropical birds to higher altitudes where the availability of resources is highest [9, 46]. However, extreme precipitation leads to the decline of reproduction due to flooding of nests, dying of broods and limitation of food provision for brood [47].

Vegetation cover is the common and most important factor for the habitat suitability of both T. ruspolii and T. leucotis. Our model predicted that desert and semi-desert scrubland (< 400 m a.s.l.) and dry evergreen Afro-montane forest (1500–3500 m a.s.l.) are suitable vegetation cover for T. ruspolii [48] whereas T. leucotis have shown wide vegetation cover range from Afro-alpine to Combretum-Terminalia woodland (above 900 m a.s.l.). The suitability of desert and semi-desert scrubland for T. ruspolii is unexpected compared to the fieldwork conducted from 1995 to 2003 [17, 25, 49] because they did not record the presence of both species in this vegetation type. However, range expansion of T. ruspolii to this vegetation type might occur during the wet season because this species is known to make localized seasonal movements [17]. Since turacos are frugivores, plant species that are found mainly in dry and moist evergreen Afro-montane forests are the main sources of fruits for these two turaco species [16, 50]. Borghesio [49] identified 10 plant species in dry evergreen Afro-montane forests as food resources, of which, Ficus species and two conifer species (Juniperus procera and Podocarpus gracilior) are the most preferred.

In this study, multiple maps were produced by applying different regularization multipliers (complexity levels). From these multiple maps, binary maps were also produced using different cut-off thresholds through an ensemble approach [41]. The use of different regularization multipliers has the advantage of enhancing the reliability of model performance and gives more confidence for taking conservation practice and management [42]. The AUC values of our model were greater than 0.90 for T. ruspolii and greater than and equal to 0.87 for T. leucotis (Table 2). These have shown that the model is found as high predictive performance for both species [38, 39]. However, the predictive performance can be influenced by different factors (variables) such as the extent of the study area and other species-related factors [51].

Current and future habitat suitability

The result of MaxEnt prediction depicted that the current suitable habitat range of T. ruspolii is found in southern Ethiopia (relatively large extent), southwestern and northwestern Ethiopia with high fragmentation and covered about 24,639.19 km². This predicted suitable habitat range is less than the extent occurrence area of the species (26,800 km²) suggested by BirdLife International [18]. Out of this predicted suitable habitat range, a survey was conducted only on the southern Ethiopia (particularly around Negele Borena, Genale, Kibre Mengist, Shakiso and Arero) with the range of 8,000 km² [17]. The model indicated that northern Ethiopia (around Lake Tana) is a potentially suitable habitat range for T. ruspolii, but its presence has not been recorded yet. On the other side, T. leucotis has wide current suitable habitat ranges than T. ruspolii and can be extended from central Ethiopia towards south, southwestern, southeastern and northwestern Ethiopia. The model estimated the current area coverage of 204,397.62 km², which is less comparable with 1.1 million km² extent occurrence area of BirdLife International’s suggestion [52].

Assembling of the future projection of T. ruspolii indicated the expansion of suitable habitats in both 2050 and 2070 relative to the current climate condition (Table 3). As model prediction and previous field surveys [17] confirmed, this turaco species preferred dry evergreen Afro-montane forest which is its main food source. The expansion of suitable habitat in the future for this species might be due to two reasons: (1) dry evergreen Afro-montane forest covers wide range compared to other vegetation types of Ethiopia next to Acacia-Commiphora woodland [48]; (2) even though there is anthropogenic pressure in this vegetation type, there is also a potential dry forest management and conservation practices in different parts of the country including plantation development to be buffering for the natural forest which is managing by the government, controlling of overgrazing, traditional forest management practiced by different Ethnic groups like Gada system, a role model of sacred grooves, especially Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church [53,54,55].

In contrast to T. ruspolii, assembling of the future projection of T. leucotis in 2050 and 2070 indicated that loss is higher than gain, and thus, the net change will be negative (Table 3). The reason for this decline in the future might be due to the rise of the mean temperature of the driest quarter (Biol9) which in turn affects the availability of food resources. T. leucotis is also preferred in moist evergreen Afro-montane forests [17] where anthropogenic pressures (such as intensification of tea and coffee productivity, human settlement and dependency of the local people on the forest products) are severe and rapid [48, 56, 57]. Intensification of coffee productivity leads to the conversion of the natural coffee forest into fully plantation coffee causing significant plant diversity losses and collapse of forest structure [56, 58].

Suitable habitat overlaps between the species

In this study, habitat suitability overlaps between T. ruspolii and T. leucotis were observed at the margin of their respective suitable habitats. Such overlap was also observed after 2001 during field survey. Before that, T. ruspolii preferred habitats of forest edge and Acacia woodland whereas T. leucotis mainly occurred in the moist (wetter) dense forests [17]. According to these authors, habitat degradation due to anthropogenic pressure is responsible for reducing the barriers between the two species. Wide suitable habitat overlap was predicted in the 2050s than the current climate condition and 2070s (Table 4). As a general trend, the area percentage of T. ruspolii that overlaps with the home range of T. leucotis is larger than the area percentage of T. leucotis that overlaps with the home range of T. ruspolli in all periods (Table 4). In other words, the model indicated that T. ruspolii will be expanded into the range of T. leucotis. This is in contrast to the field survey of 2003 [17]. Whatever the case, the overlapping of the two species’ habitat will lead to resource competition. Furthermore, hybridization between these two species was observed since 2001 [59] which indicates the presence of habitat overlap. Thus, the widespread hybridization at the overlap ranges leads to the risk of genetic erosion of the Nearly Threatened T. ruspolii [60] and which in turn leads to extinction despite the availability of suitable habitat in future climatic conditions.

Conclusions

The study set out to determine the distribution and habitat suitability of T. ruspolii and T. leucotis using bioclimatic and non-bioclimatic factor. Model performance is found in high accuracy for T. ruspolii while good performance for T. leucotis. Precipitations of the driest month, temperature seasonality, and vegetation cover are the most contributor variables for the habitat suitability prediction of T. ruspolii while mean temperature of the driest quarter and vegetation cover for T. leucotis. The extent of both the current and future suitable habitat of T. ruspolii is less than that of T. leucotis. However, under future climate conditions, the extent of its suitable habitat is expected to be increased while this decreases for T. leucotis. Suitable habitat overlapping between the two species is also observed at the margin of their respective habitat types in current and future climate conditions. Therefore, understanding the distribution of current and future suitable habitats of these turaco species can provide valuable information to implement conservation practices for the species and the regions as well. A comprehensive survey for population assessment in highly suitable habitats is also fundamental to understanding the current conservation status of both species. Future research may also consider the application of numerous different models and their ensemble approach.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Pecl GT, Araujo MB, Bell J, Blanchard J, Bonebrake TC, Chen I, Clark TD, Colwell RK, Danielsen F, Evengard B, Robinson S, et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science. 2017;355(6332):1–9.

Wagner B, Baker PJ, Stewart SB, Lumsden LF, Nelson JL, Cripps JK, Durkin LK, Scroggie MP, Nitschke CR. (2020) Climate change drives habitat contraction of a nocturnal arboreal marsupial at its physiological limits. Ecosphere11: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3262.

Kufa CA, Bekele A, Atickem A. Impacts of Climate Change on Predicted Habitat suitability and distribution of Djaffa Mountains Guereza (Colobus guereza gallarum, Neumann 1902) using MaxEnt Algorithm in Eastern Ethiopian Highland. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2022;35:e02094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02094.

Head MJ, Steffen W, Fagerlind D, Waters CN, Poirier C, Svitski J et al. (2022) The great acceleration is real and provides a quantitative basis for the proposed Anthropocene Series/Epoch. Episodes J Int Geoscience. 2022; 45:359 – 76. https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2021/021031.

Huntley B, Collingham YC, Green R, Hilton GM, Rahbek C, Willis SG. Potential impacts of climatic change upon geographical distributions of birds. Ibis. 2006;148:8–28.

Sekercioglu CH, Schneider SH, Fay JP, Loarie SR. Climate Change, Elevational Range shifts, and Bird extinctions. Conserv Biol. 2007;22(1):140–50.

Freeman BG, Class Freeman AM. Rapid upslope shifts in New Guinean birds illustrate strong distributional responses of tropical montane species to global warming. PNAS. 2014;111:4490–4.

Zucchetto MF, Da Silveira NS, Prasniewski VM, Arnhold T, Sobral-Souza T, de Pinho JB. Effects of future climate change on the geographical distribution of a bird endemic to south American floodplains. Avian Conserv Ecol. 2021;16(2):29. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01893-160229.

Freeman B, Scholer M, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Fitzpatrick J. Climate change causes upslope shifts and mountaintop extirpations in a tropical bird community. PNAS. 2018;115:11982–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804224115. https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/.

Bladon AJ, Donald PF, Collar NJ, Denge J, Dadacha G, Wondafrash M, et al. Climatic change and extinction risk of two globally threatened Ethiopian endemic bird species. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0249633. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249633.

Li X, Liu Y, Zhu Y. The effects of Climate Change on birds and approaches to response. IOP Conf Series: Earth Environ Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1011/1/012054.

Sekercioglu CH, Primack RB, Wormworth J. The effects of climate change on tropical birds. Biol Conserv. 2012;148:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.10.019.

Mota FM, Heming NM, Morante-Filho JC, Talora DC. Amount of bird suitable areas under climate change is modulated by morphological, ecological and geographical traits. Front Ecol Evol. 2022;10:987204. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.987204.

Malanotte ML, Machado-de-SouzaT, Campos R, Petkowicz CL, Varassin IG. How do fruit productivity, fruit traits and dietaryspecialization affect the role of birds in a mutualistic network? J Trop Ecol. 2019;35:213–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467419000178.

Yatsiuk Yand Wesołowski T. Diversity and abundance of large tree holes used by Tawny owls Strixaluco in lowland temperate forests. Bird Study. 2020;67:331–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2020.1869179.

Borghesio L, Ndanganga PK. Habitat selection and the conservation status of Fischer’s turaco. Tauracofischerion Unguja Tanzan Oryx. 2003;37:444–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605303000814.

Borghesio L, Giannetti F, Ndanganga K, Shimeli A, Borghesio A, Rizzoe D, Fufaf K. A reassessment of the conservation status of Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco. Tauracoruspolii Bull ABC. 2004;11:104–11.

BirdLife International. (2022) Species factsheet: Tauraco ruspolii. http://www.birdlife.org accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Banda LB, Tassie N. Modeling the distribution of four-bird species under climate change in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Biol Sci. 2018;17:1–17.

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Model. 2006;190:231–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026.

Elith J, Leathwick JR. (2009) Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2009;40(1):677 – 97. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159.

Fashing PJ, Nguyen N, Demissew S, GizawA, AtickemA MA, Stenseth NC. Ecology, evolution, and conservationof Ethiopia’s biodiversity. PNAS. 2022;119(50):e2206635119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206635119.

Ash J, Atkins J. Birds of Ethiopia and Eritrea: an atlas of distribution. London: A and C Black Publishers Ltd.; 2009.

Redman N, Stvenson T, Fanshawe J. Helm Field Guide: birds of the Horn of Africa. London: Christopher Helm; 2009.

Borghesio L, Massa R. Status and conservation of Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco. Tauracotuspolii Ostrich. 2000;71:355–8.

Adugna C, Afework B. Avian diversity, species composition and habitat association in Lebu natural protected forest, southwest Showa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Biol Sci. 2018;17:155–67.

Abie K, Tilahun B, Feyisa A, Kumssa T, Amare A. Bird species diversity and distribution in case of protected area. Species. 2019;20:90–100.

Jemal Z, Girma Z, Mengesha G. Bird Diversity in Nensebo Moist Afromontane Forest Fragment, South Eastern, Ethiopia. Open Ornithol. 2020;J3:1–9. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874453202013010001.

Brown JL. SDMtoolbox: a python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. Methods Ecol Evol. Southern Illinois University; 2014.

Guisan A, Thuiller W, Zimmermann N. Habitat suitability and distribution models with application of R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

Peterson AT, Soberon J, Pearson RG, Anderson RP, Martinez-Meyer E, Nakamura M, Araujo MB. Ecological niches and Geographic distributions. Princeton University Press; 2011.

Fick SE, Hijmans RJ. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2017;37:4302–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086.

Jarvis A, Reuter HI, Nelson A, Guevara E. (2008) Hole-filled SRTM for the globe Version 4. https://cgiarcsi.community/data/srtm-90m-digital-elevation-database-v4-1/accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Naimi B, Hamm NA, Groen TA, Skidmore AK, Toxopeus AG. Where is positional uncertainty a problem for species distribution. Modelling? Ecography. 2014;37(2):191–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00205.x.

Barbet-Massin M, Jiguet F, Albert CH, Thuiller W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: how, where and how many? Methods Ecol Evol. 2012;3:327–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00172.x.

Phillips SJ, Dudik M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography. 2008;31:161–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.5203.x.

Young N, Carter L, Evangelista P. (2011) A MaxEnt Model v3.3.3e Tutorial (ArcGIS v 10). Colorado State University.http://ibis.colostate.edu/webcontent/ws/coloradoview/tutorialsdownloads/a_maxent_model_v7 Accessed 25 March 2022.

Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–93. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.328761.

Elith J, Phillips SJ, Hastie T, Dud M. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Divers Distrib. 2011;17:43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x.

Ahmed SA, Chala D, Kufa CA, Atickem A, Bekele A, Svenning J, Zinner D. Potential changes in the extent of suitable habitats for geladas (Theropithecus gelada) in the Anthropocene. Ecol Evol. 2023;23:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-023-02173-3.

Araujo M, New M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22:42–7.

Chala D, Brochmann C, Psomas A, Ehrich D, Gizaw A, Masao CA, Bakkestuen V, Zimmermann N. (2016) Good-bye to tropical alpine plant giants under warmer climates? Loss of range and genetic diversity in Lobelia rhynchopetalum Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2603.

Redecker A, Burian J, Moos N, Macku K. Spatial analysis in geomatics. In: Paszto V, Jurgens C, Tominc P, Burian J, editors. Spationomy: spatial exploration of economic data and methods interdisciplinary analytics. Switzerland: Springer; 2020. pp. 65–92.

Hu Z, Liang M, Knapp A, Xia J, Yuan W. Are regional precipitation-productivity relationships robust to decadal-scale dry period? J Plant Ecol. 2022;15:711–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtac008.

Gwitira I, Murwira A, Shekede M, Masocha M, Chapano C. Precipitation of the warmest quarter and temperature of the warmest month are key to understanding the effect of climate change on plant species diversity in southern African savannah. Afr J Ecol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12105.

Neate-Clegg M, O’Brien T, Mulindahabi F, Sekercioglu C. A disconnect between upslope shifts and climate change in an afrotropical bird community. Conserv Sci Pract https//. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.291.

Fisher R, Wellicome T, Bayne E, Poulin R, Todd L, Ford A. Extreme precipitation reduces reproductive output of an endangered raptor. J Appl Ecol https//. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12510.

Asefa M, Cao M, He Y, Mekonnen B, Song X, Yang J. Ethiopian vegetation types, climate and topography. Plant Divers. 2020;42:302–11.

Borghesio L. Field observation on Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco (Tauracoruspolii). Scopus. 1997;19:83–91.

Yeboah S, Deikumah JP, Henaku-Owusu E. The Status of three species of turacos in the Kakum Conservation Area in the Central Region. Ghana West Afr J Appl Ecol. 2008;13:1–8. https://doi.org/10.4314/wajae.v13i1.40578.

Grenouillet G, Buisson L, Casajus N, Lek S. Ensemble modelling of species distribution: the effects of geographical and environmental ranges. Ecography. 2011;34:9–17.

BirdLife International. (2022) Species factsheet: Tauraco leucotis. http://www.birdlife.org accessed 17 Aug 2022.

Wassie A, Sterck F, Teketay D, Bongers F. Tree regeneration in Church forests of Ethiopia: effects of microsites and Management. Biotropica. 2009;41:110–9.

Lemenih M, Bongers F. Dry Forest of Ethiopia and their silviculture. In: Gunter S, et al. editors. Silviculture in the Tropics PP. Berlin: Springer; 2011. pp. 261–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19986-817.

Masresha G, Melkamu Y. The status of dry evergreen afro-montane forest patches in Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Int J Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8071761.

Hundera K, Aerts R, Fontaine A, Van Mechelen M, Gijbels P, Honnay O, Muys B. Effects of Coffee Management Intensity on Composition, structure, and Regeneration Status of Ethiopian Moist Evergreen afro-montane forests. Environ Manage. 2013;51:801–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-9976-5.

Tadesse G, Zavaleta E, Shennan C, Simmons M. Policy and demographic factors shape deforestation patterns and socio-ecological processes in southwest Ethiopian coffee agro-ecosystems. Appl Geogr. 2014;54:149–59.

Zewdie B, Tack AJ, Ayalew B, Wondafrash M, Nemomissa S, Hylander K. Plant biodiversity declines with increasing coffee yield in Ethiopia’s coffee agro-forests. J Appl Ecol. 2022;59:1198–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14130.

Lernould JM, Seitre R. Observation d’hybridesnaturels entre Le Touraco à joues blanches Tauracoleucotis et le touraco du Prince Ruspoli, T. Ruspolii. Alauda. 2002;70:247–51.

Lernould JM, Seitre R. Does hybridisation with White-cheeked Turaco Tauracoleucotis represent a threat for Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco. T Ruspolii? Bull ABC. 2004;11:112–5.

Acknowledgements

Addis Ababa University, Department of Zoological Sciences provided facilities to carry out this research.

Funding

Not available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. involved in data compilation, modeling, analyzing the output and drafting manuscript. C.A., A.S., and H.T. involved during title selection, data analysis, and revising the manuscript. M.T., M.Y., A.A., A.B. and B.A. revised the manuscript. We would like to clarify that the work presented here is original research that has not previously been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aligaz, M.A., Kufa, C.A., Ahmed, A.S. et al. Distribution and extent of suitable habitats of Ruspoli’s Turaco (Tauraco ruspolii) and White-cheeked Turaco (Tauraco leucotis) under a changing climate in Ethiopia. BMC Ecol Evo 24, 83 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-024-02245-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-024-02245-y