Abstract

Background

Standing genetic variation is important especially in immune response-related genes because of threats to wild populations like the emergence of novel pathogens. Genetic variation at the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which is crucial in activating the adaptive immune response, is influenced by both natural selection and historical population demography, and their relative roles can be difficult to disentangle. To provide insight into the influences of natural selection and demography on MHC evolution in large populations, we analyzed geographic patterns of variation at the MHC class II DRB exon 2 locus in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) using sequence data collected across their entire broad range.

Results

We identified 31 new MHC-DRB alleles which were phylogenetically similar to other cervid MHC alleles, and one allele that was shared with white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). We found evidence for selection on the MHC including high dN/dS ratios, positive neutrality tests, deviations from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) and a stronger pattern of isolation-by-distance (IBD) than expected under neutrality. Historical demography also shaped variation at the MHC, as indicated by similar spatial patterns of variation between MHC and microsatellite loci and a lack of association between genetic variation at either locus type and environmental variables.

Conclusions

Our results show that both natural selection and historical demography are important drivers in the evolution of the MHC in mule deer and work together to shape functional variation and the evolution of the adaptive immune response in large, well-connected populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The amount of genetic variation in a population is directly associated with its potential to adapt or evolve in new environments [1,2,3]. Populations capable of rapid adaptive responses can maintain biodiversity in rapidly changing environments, whereas those with lower adaptive capacity are vulnerable to population declines or extinction. Variation at functional genes involved in immune response is of increasing concern as wildlife diseases emerge as serious threats to populations, as seen in examples like amphibian chytridiomycosis [4, 5], white-nose syndrome in bats [6,7,8,9], and chronic wasting disease in ungulates [10,11,12,13]. Genes in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are some of the most polymorphic in vertebrate genomes, maintained by natural selection in response to an ever-changing environment of pathogens [14,15,16,17,18]. Specifically, exon 2 of the MHC DRB gene codes for extracellular antigen receptors and affects the activation of the adaptive immune system. Genetic diversity at this locus has evolved under pathogen-mediated selection in addition to demographic processes like genetic drift and gene flow that affect variation genome-wide, making the MHC an important region for understanding how functional diversity is maintained in natural populations [19,20,21].

Pathogen-mediated selection at the MHC can occur by way of directional selection in response to the presence of specific pathogens [22] or by balancing selection through non-mutually exclusive mechanisms including heterozygote advantage, negative frequency dependence, and fluctuating selection from heterogenous host–pathogen dynamics [23,24,25,26,27]. MHC variation in host populations is maintained by co-evolution between pathogen populations and the host immune response [28,29,30,31,32]. Sexual selection may also play a role as MHC allelic richness has been linked with sexually selected traits [18, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Additionally, environmental factors may indirectly affect selection on the MHC by changing the pathogen load in an area [40, 41].

Historical population demography also influences MHC variation and can be challenging to disentangle from the effects of natural selection. Strong genetic drift in small and isolated populations reduces variation at all genes, including those of the MHC [42,43,44,45,46,47]. Comparing patterns of genetic variation at functional and neutral loci can help isolate the role of selection in maintaining MHC variation in natural populations. When the MHC evolves by neutral processes such as genetic drift and gene flow, the MHC would be expected to show patterns of variation similar to neutral loci [48,49,50], whereas selection would cause patterns of MHC variation to diverge from neutral loci, potentially mirroring patterns of variation in the selective agent [51,52,53]. For example, local adaptation is present where MHC differentiation is greater than that in neutral markers [51,52,53], balancing selection is present when MHC differentiation is weaker than at neutral markers [29, 31, 32], and MHC differentiation could be no different than that of neutral markers where weak selection or strong drift effects occur [49, 50]. Previous studies have used this comparative approach to learn more about adaptation at the MHC [42, 45,46,47, 54, 55]. However, many of these studies have considered populations that are small, isolated, or have experienced recent bottlenecks [32, 42, 45, 47, 49, 56,57,58,59]. We might expect different outcomes for large, highly connected populations, where genetic drift is not as prominent, and natural selection can guide adaptation of complex traits [60].

To better understand the relative roles of natural selection and demography on MHC evolution in large populations, we analyzed geographic patterns of variation at the MHC class II DRB exon 2 locus in mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and compared it to paired data from neutral loci based on microsatellite markers. Mule deer are distributed in diverse environments across a broad geographical range, spanning over 40° of latitude. In these varied environments, mule deer encounter a wide variety of infectious (viral, bacterial, prion) and parasitic (protozoan, helminths, arthropods) agents (Davidson et al. [61], Samuel et al. [62], Williams and Barker [63]). These agents can drive the evolution of ungulate MHC through natural selection [28, 64]. Historical demography will also shape variation at the MHC and genome-wide, with its role determined in large part by the species’ biogeographic history and long-term effective population size. Unlike previous studies, we take a broad look at mule deer MHC diversity by surveying across the entire geographic range. Mule deer populations are generally large, well connected, and genetically diverse [65], both today and historically. We have sampled core populations from a single evolutionary lineage, whose shared biogeographic history facilitates direct comparison of functional and neutral diversity range-wide. Comparing range-wide patterns of adaptive and neutral variation will help disentangle the relative influence of evolutionary mechanisms impacting the maintenance of MHC variation at a broad scale in mule deer.

Results

MHC sequencing and phylogeny

We successfully sequenced the entire 250 bp MHC class II DRB exon 2 in 384 individuals across 16 populations of mule deer. From sequencing, we obtained a total of 552,769 reads. Filtering resulted in an average of 1452 reads per individual (which ranged from 104 to 5000 reads) for 380 individuals (Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Table S1). Four individuals, each from a different population, yielded few reads (< 100) and were removed from further analysis (n for each population shown in Tables 1 and 2). Following the characteristic high polymorphism rates of MHC genes, we found 69 variable sites, corresponding to amino acid changes at 37 of the 83 codons (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). All alleles were unique at the amino acid level. The number of amino acid differences between alleles ranged from 1 to 26. Each individual had a maximum of two alleles, consistent with the presence of a single MHC-DRB locus (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). One individual showed three alleles, but one of the called alleles was an artifact with low read count (Population AB-728, read numbers included 553, 514 and 179) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1, Table S1). Zero alleles were called for six individuals, however, read numbers permitted unambiguous manual allele assignment (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).We observed 31 new alleles and one allele (Odvi-DRB*09) previously recorded in white-tailed deer [66]. The new mule deer alleles (Odhe-DRB*01-31) were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MZ450871-MZ450901. Although four alleles (Odhe-DRB*23, Odhe-DRB*25, Odhe-DRB*27, and Odhe-DRB*31) were observed only once, each had over 500 reads when present and thus were considered to be true alleles and included in downstream analyses (Table 1, Additional file 1: Table S1, Fig. S1).

The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showed little evidence for distinct MHC lineages among cervid species (Fig. 1). The bootstrap support values were low (< 0.53) throughout the tree. We observed some clustering of the three moose sequences and a cluster containing all three caribou sequences. Mule deer, white-tailed deer, sika deer, elk, and roe deer were all polyphyletic, though most Odocoileus sequences were in a clade separate from other cervids, albeit with weak support (0.34; Fig. 1).

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of MHC DRB exon 2 allele sequences. Sequences included here are the 31 new mule deer alleles (Odhe, Odocoileus hemionus) shown by blue circles, 30 white-tailed deer alleles (Odvi, Odocoileus virginianus) shown by red squares, and outgroups including moose (Alal, Alces alces; green triangles), roe deer (Caca, Capreolus capreolus; purple diamonds), elk (Ceel, Cervus elaphus; orange stars), sika deer (Ceni, Cervus nippon; navy crosses), and caribou (Rata, Rangier tarandus; yellow pentagons), rooted with an orthologous cattle DRB sequence (Bola, Bos taurus). Nodes are labeled with bootstrap support values. The shared allele between mule deer and white-tailed deer (Odvi-DRB*09) is shown with a red arrow

Population genetic data analysis

MHC allelic richness varied among populations while microsatellite allelic richness remained relatively constant (Tables 1 and 2). The number of observed MHC alleles in each population ranged from 6 in the northernmost population (YK-SE) to 17 at middle latitudes (NV-PC and WY-SH), with only two populations having private alleles (MT-RV and TX-AL; Odhe-DRB*23, Odhe-DRB*25, Odhe-DRB*27, Odhe-DRB*30 and Odhe-DRB*31; Tables 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). The most common MHC allele (Odhe-DRB*01) was the only allele observed in all populations (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). Although white-tailed deer are primarily found in the eastern half of North America, the shared allele between mule deer and white-tailed deer (Odvi-DRB*09) was not restricted to populations along the contact zone (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). As with MHC, microsatellite allelic richness was lowest at the most northerly site YK-SE (4.19), but in contrast to MHC diversity, was highest at other northern sites AB-OR and MT-RV (5.74 and 5.71, respectively; Table 2). Private alleles in microsatellite loci were observed in nine of the 16 populations, with the southwestern site AZ-KF having the highest private allelic richness (0.28; Table 2). Overall, allelic richness was positively correlated between MHC and microsatellites (r = 0.697; p = 0.003). Observed heterozygosity ranged more widely for MHC than microsatellites and was not significantly correlated between the two genetic marker types (r = 0.092; p = 0.73). The microsatellite loci were at HWE in most populations (with 4/144 tests deviating from HWE across the 9 microsatellite loci), whereas deviations from HWE were evident at the MHC for 8 of 16 populations (Tables 1 and 2). Neutral and demographic processes are predicted to affect all loci similarly, thus the presence of widespread heterozygote deficiencies relative to Hardy–Weinberg expectations specifically in the MHC suggest selection at that locus. We observed no evidence of genetic structure at either locus type from the STRUCTURE software approach (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). DAPC analysis of both MHC and microsatellites revealed little overall population structure, with most population clusters showing admixture (Fig. 3). We saw a slight latitudinal trend in the microsatellite DAPC scatterplot along axis 1 that was not present in the MHC data (Fig. 3). TX-AL and YK-SE populations were slightly more distinct from other populations in both analyses (Fig. 3).

Sampling sites and MHC allele frequencies. 24 individuals were sampled from each of 16 sites spanning the range of mule deer (shown in light grey) between 1995 and 2005. The orange circles show the location of the sampling sites. Site details can be found in Additional file 2. The pie charts represent the proportion of different MHC alleles found in each population, with each allele’s respective color shown in the legend chart (1 = Odhe-DRB*01). The top 10 most common alleles are labeled in the legend with asterisks. Only the most common allele, Odhe-DRB*01, shown in the lightest blue, was found in every population. The shared allele between mule deer and white-tailed deer, Odvi-DRB*09, is shown in the darkest brown

Cluster analysis using Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC). Scatterplots show the DAPC of genotypes from the 16 mule deer populations at (a) the microsatellite loci and (b) the MHC locus. Each individual is represented as a point, colored based on its population of origin, with red being southern or low latitudes and blue being northern or high latitudes. Populations are surrounded by 95% inertia ellipses

We observed evidence for selection on the MHC class II DRB exon 2 in mule deer. dN/dS ratios (ω) above 1 for the full exon (ω = 1.18) and the ABS sites (ω = 2.05) indicate positive selection, whereas non-ABS sites showed evidence of purifying selection (ω = 0.59). Further support for positive selection comes from comparing codon substitution models; models M2a and M8 provided a better fit to the MHC sequence data than M1a and M7 (p < 0.01). Twelve sites were identified as under positive selection in model M8 (posterior probability > 0.95), nine of which were also identified in model M2a (Fig. 4). Ten of the twelve sites identified as being under positive selection corresponded to human HLA antigen binding sites (Fig. 4). Neutrality tests showed positive values across all populations (Table 1). Fu and Li’s D* and F* tests showed six and five populations with statistically significant values, respectively (Fu and Li’s D*: AZ-30, CO-SJ, KS-BD, NV-PC, SK-14, and YK-SE; Fu and Li’s F* significant values included the same as D* except for NV-PC). The YK-SE population showed statistically significant values for Tajima’s D as well as Fu and Li’s D* and F* and the population showed the highest value for Fu’s Fs. Significant values suggest that selection may be driving MHC variation in these populations, and positive values point to balancing selection, recent population bottlenecks, or the presence of intermediate frequency alleles.

Genetic differentiation between populations was not driven by the same evolutionary processes in both marker types (Mantel r = 0.10, p = 0.28). Whereas both MHC and microsatellite differentiation could be explained using a simple IBD pattern of gene flow, the slope was significantly steeper for MHC (0.180) than microsatellites (0.022) (p < 0.0001; Fig. 5). Both marker types experience identical gene dispersal patterns, thus stronger IBD (steeper slope) suggests the presence of evolutionary factors that act exclusively on MHC variation.

Environmental analysis

Although environmental variables may indirectly affect genetic variation through their influence on pathogen abundance and diversity, we found that neither MHC nor microsatellite diversity were significantly correlated with latitude, elevation, or any of the bioclimatic variables we tested. Mean-centered allelic richness values were similar across latitudes (Fig. 6) and a low coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.0028 for MHC and 0.0007 for microsatellites) suggests that latitude is not an important driver of among-population variation in allelic richness in our system. Investigation of environmental variables revealed many that were correlated with each other; eleven predictors were removed from analysis leaving latitude, longitude, elevation, mean annual temperature (MAT), seasonality (TD), mean annual precipitation (MAP), and relative humidity (RH) variables in the RDAs. The first two axes in the microsatellite RDA explained 46% and 23% of the variance in allelic richness across populations and both the full RDA model and axis 1 were significant (p = 0.05 and 0.03; Fig. 7a). Populations tended to follow logical patterns in terms of relation to environmental predictors; populations located in southwestern North America tended to be positively related to mean annual temperature and negatively related to mean annual precipitation and seasonality, while northern populations showed the opposite relationships (Fig. 7a). The MHC-based RDA showed similar spatial patterns of populations; sites which had higher latitudes also were negatively related to mean annual temperature, but positively related to seasonality (Fig. 7b). Axes 1 and 2 explained 27% and 21% of the variance, respectively, in allele frequencies for MHC across the 16 populations (Fig. 7b). However, the full RDA model and all axes within the MHC RDA were not significant (all p > 0.1). These results do not provide evidence to support the hypothesis that specific climatic conditions are influencing pathogen load in a way that generates a strong selective force on MHC diversity in mule deer populations.

Redundancy Analysis (RDA) for microsatellites and MHC. (a) Axes 1 and 2, explaining 46% and 23% of the variance, respectively, in allelic richness for 9 microsatellite loci across 16 populations. (b) Axes 1 and 2, explaining 27% and 21% of the variance in allele frequencies for the MHC locus across 16 populations. Points for each plot are colored by population according to latitude. Vectors in blue show constraining axes, or environmental predictors, pointing in the direction of positive contribution, including latitude (Lat), longitude (long), elevation (elev), mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), temperature difference between warmest and coldest months (TD), and relative humidity (RH)

Discussion

Understanding the relative effects of natural selection and demography at functionally important immune genes in wildlife is increasingly important as emerging epizootic and zoonotic diseases threaten animal and human health [67, 68]. Our comparative analysis of range-wide variation at the MHC and neutral microsatellite loci in a widespread and mobile species adds much to the developing picture of how evolutionary mechanisms work collectively to shape allelic variation at a broad scale. In this study, we found that while selection plays an inherent role in the evolution of the MHC in mule deer, demography is also a significant predictor of broad scale patterns of MHC variation. Population differentiation was stronger at the MHC than at neutral microsatellite loci, suggesting that there has been selection for locally adapted MHC variation driving differentiation beyond that arising from neutral evolutionary processes (i.e., drift and gene flow). Yet, similar patterns of variation between MHC and neutral loci show that the microsatellite-based signatures of historical demography persist in the face of selection, and that demography is a key contributor to functional diversity at a broad scale, even in large and mobile populations where drift is expected to be weak.

Patterns of polymorphism in the mule deer MHC revealed classic signatures of natural selection. We found high dN/dS ratios and positive neutrality test values in the MHC sequences, on the entire exon and in peptide-binding regions. Tests of codon substitution models also revealed that the codon sites that were under selection closely matched the inferred antigen-binding sites from the human HLA molecule. Our results showing that selection acts on functional codons within the MHC are consistent with previous studies in ungulates and other vertebrates, namely white-tailed deer [69, 70], musk deer [43], red deer [71, 72], moose [58], cattle and other ruminants [21, 73], Nile tilapia [74] and prairie chickens [75].

Signatures of selection that we observed at the MHC were not present in the neutral microsatellite loci. Heterozygote deficiencies at the MHC locus were found in 50% of the mule deer populations surveyed, whereas microsatellites were consistently in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (6 loci exhibited no deviations, and the other 3 loci exhibited heterozygote deficiencies in 1 or 2 populations). Other cervids also exhibit heterozygote deficiencies at the MHC DRB locus, including in white-tailed deer, caribou, and moose [58, 66, 69, 76]. An observed heterozygosity excess would be expected if there were a fitness advantage for MHC heterozygotes, through either pathogen-mediated natural selection or sexual selection (MHC-disassortative mating). However, there are several potential reasons why we might see widespread heterozygote deficiencies in our study, including PCR error (null alleles), cryptic substructure (Wahlund effect), or selection against heterozygotes. Our PCR amplification, based on read numbers, shows no evidence for poorly bound primers or errors in sequencing. Cryptic population structure is likely present in mule deer at a fine scale (e.g., family groups), but is likely washed out by range-wide patterns that show a lack of broad-scale population structure [65]. Selection against heterozygotes is rare, but not unheard of. For example, in caribou, high heterozygosity is associated with decreased immunocompetence, offering a potential mechanism limiting excess heterozygosity in ungulates [76]. Further exploration of immunological costs associated with heterozygosity would help determine whether mule deer experience similar pressures.

Another signature of selection in our dataset was stronger MHC divergence over the same geographic space compared to the microsatellites, as seen by the steeper slope in the IBD analysis. This supports the idea that while neutral processes may establish a baseline of genetic diversity across all loci, natural selection drives additional differentiation at the MHC locus. Stronger population differentiation at the MHC than at neutral loci has also been seen in other vertebrates [51,52,53, 77]. Most previous studies have compared variation in small, isolated, or recently bottlenecked populations [32, 42, 45, 47, 49, 56, 57], where drift can have an outsized impact on adaptive variation [44, 54, 78]. Moose experienced a historical bottleneck that reduced both neutral and MHC variation; low levels of variation are likely maintained by solitary social behavior and low dispersal [58, 79,80,81]. White-tailed deer also experienced historical bottlenecks, but drift mitigated by accelerated recovery through extensive translocation and the species’ high mobility [82] likely kept MHC diversity high [66, 69]. Mule deer are not known to have experienced severe historical bottlenecks (Latch et al. [83]), and large and well-connected populations would be expected to maintain high variation at the MHC and genome-wide. With negligible genetic drift, differentiation patterns at the MHC are expected to coincide with differences in pathogen prevalence, which are dynamic over both space and time [84]. Examining how MHC variation changes with spatially or temporally varying parasite pressure would yield additional insight into the relative roles of drift and selection (e.g., [24, 85,86,87]).

Pathogen mediated selection-based spatial genetic structure at the MHC may be mediated by one or more mechanisms including heterozygote advantage, frequency-dependent selection, or varying pathogen pressures. The difference in environmental conditions across populations at a broad scale may foster differences in pathogen abundance and community composition, creating variable selective pressure across the mule deer range [88,89,90]. The true landscape of parasite-induced selection pressure is not well described in mule deer but in other species has been associated with latitude [86, 91,92,93,94], or environmental factors [95], often with latitude serving as a proxy for environmental factors. Spatially heterogenous selection would be expected to maintain polymorphism and facilitate local adaptation [30, 51, 53, 85, 96,97,98]. High polymorphism across populations at MHC genes may help populations respond to a wide variety of pathogens and increase population fitness, though costs to maintain diversity may impose an upper limit [76]. In mule deer, low rates of gene duplication and allelic richness compared to other mammals suggest that such a trade-off may not be critical in ungulates [18]. Additionally, signatures of local adaptation may be disrupted due to the high rates of gene flow seen in mule deer, which can introduce maladapted genes to a population.

Historical demography works to further shape MHC evolution in mule deer, and its effects are evident even in large and well-connected populations. DAPC analysis revealed similar patterns of genetic structure in both MHC and microsatellite datasets, and neither dataset showed strong correlations with specific environmental variables. Both the microsatellites and the MHC showed patterns of IBD, which suggests that neutral genetic processes are important in shaping diversity at both neutral and functional loci. MHC allelic richness was overall higher than microsatellites, but when corrected for overall levels of variation was similar to microsatellites and did not show statistically significant latitudinal or environmental trends that might be expected if parasite-mediated selection was the driving force behind MHC evolution [93, 99]. The 16 populations studied here all have historically large effective population sizes and are from the same evolutionary lineage, suggesting that they have experienced similar long-term evolutionary histories [65].

There are several reasons why we could see genomic signatures of both selection and demography in this system. One possibility is that high effective population sizes and high levels of standing genetic variation may contribute to natural selection that is widespread and sustained, yet weak. A combination of demographic influence and weak selection across many functional loci has been shown in mule deer, albeit in a different adaptive context [100]. Weak pathogen-mediated selection is feasible in deer, where pathogens are often rare relative to their host or have low virulence [101]. A second possible mechanism where signatures of both selection and demography could be maintained in MHC class II variation is if other genes are important in pathogen response. MHC genes are highly linked in mammals [102, 103], but genomic signatures of selection on different MHC classes have been shown to vary depending on species [104, 105]. Along these lines, a virulent or prevalent pathogen may not trigger a class II response but may be defended against via another pathway, such as toll-like receptors and cytokines that have been associated with disease resistance and survival in wild populations [106,107,108]. A third possibility is that the MHC diversity we estimated using genomic DNA sequences may not reflect the expressed diversity, thus providing an incomplete picture of selection. For example, a comparison of cDNA and genomic DNA in songbirds revealed fewer expressed MHC-I alleles than predicted by sequence data [109]. Comparing our genomic variation in MHC class II with cDNA diversity would show whether expressed diversity displays stronger signatures of selection in mule deer.

Our phylogenetic analysis of evolutionary relationships between MHC DRB exon 2 alleles in mule deer and other cervids showed MHC alleles from similar species tend to cluster together. The white-tailed deer and mule deer MHC alleles tended to be intermixed but formed their own clade. Our phylogenetic tree was similar to the MHC-DRB2 tree from Ivy-Israel et al. [69], and indeed used many of the same taxa, though our tree had higher bootstrap supports throughout. In both cases, overall support is low throughout the tree, which is expected in the MHC as it is subject to a high degree of homoplasy [110]. Shared alleles across species and polyphyletic grouping appears to be common for the vertebrate MHC [42, 75, 111, 112]. We observed one shared allele between mule deer and white-tailed deer (Odvi-DRB*09). This could be an example of a trans-species polymorphism, where similar historical biogeography between species can lead to shared alleles or similar MHC variation patterns [113, 114]. Because white-tailed deer and mule deer are closely related species that share many pathogens [115], selection may have maintained the shared allele to confer resistance to a common pathogen. Alternatively, it is possible that the shared allele is an independent identical-by-state mutation. The fact that the shared allele is more recently derived according to the phylogenetic tree, and the fact that it is present in populations where white-tailed and mule deer ranges do not overlap suggests that it may not be a true trans-species polymorphism. A broader survey of Odocoileus and related species from North America would help determine the extent and evolutionary history of this shared polymorphism. More detailed studies that characterize the pathogen community and connect estimates of fitness for particular alleles at the MHC and other immune genes are needed to better understand how natural selection influences the evolution of the adaptive immune response in ruminants.

Conclusions

Comparing spatial patterns of variation at functional and neutral loci reveals that both natural selection and historical demography are important mechanisms driving MHC evolution at a broad scale. Our findings for large, well-connected populations add to the emerging picture of how evolutionary mechanisms work collectively to shape functional variation and the evolution of the adaptive immune response.

Methods

Sample collection

Odocoileus hemionus tissue samples were collected across the species’ latitudinal range, from animals harvested by hunters between 1995 and 2005 (82% of samples collected in 2000–2001). We sampled 24 individuals from each of 16 populations (Fig. 2). Populations were located in the core mule deer range (the ‘MD’ genetic cluster identified in [65]) and outside the known hybrid zone with black-tailed deer in the Pacific Northwest [100, 116]. Sampled animals were at least 1 year old and 63.8% of individuals were male. Sampled animals were unrelated (all pairwise relatedness values across the dataset were < 0.0312).

Genotyping at microsatellite and MHC loci

DNA was extracted from all 384 samples using a modified ammonium acetate protein precipitation protocol [117]. DNA was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis and standardized to ~ 10 ng/µL in TLE buffer (10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 mm EDTA). All samples were previously genotyped at a panel of 9 unlinked microsatellite loci (Odh_E, Odh_K, Odh_C, BM848, C273, Odh_G, Odh_P, RT24, T40; [65]), which we used in this study for comparative purposes. Approximately 5% of the tissue samples (n = 20) were genotyped twice to estimate microsatellite genotyping error rate. We identified one instance of allelic dropout in the 200 repeated genotypes (0.5% error rate), in line with previous estimates of error rate for these same loci (0.6%, [118]). The final microsatellite dataset contained 0.4% missing data (15 missing genotypes out of 3840 total genotypes) and exhibited no linkage disequilibrium or evidence for null alleles. We observed no differences in genetic diversity among years (using the only 2 years with sufficient sample sizes) or between sexes, so the total dataset was used for all analyses.

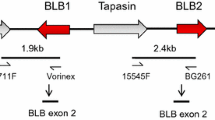

We amplified a 390 bp product containing the entire MHC class II DRB exon 2 in 20 µL Polymerase Chain Reactions (PCRs) containing 10 ng genomic DNA, 0.5 µM each primer (LA31 and LA32; [119]), 200 µM dNTPs, 1 U Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), and 1× Phusion buffer. Primers were modified with adapter sequences on both primers and a 10 bp individual barcode on the forward primer. PCRs were performed with an initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 25 cycles of 98 °C for 15 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 98 °C for 15 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were cleaned with a Qiagen PCR Purification Kit followed by Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads, and DNA concentration was quantified on a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer. PCR products were pooled into eight pools, each with 48 samples, and bead cleaned twice more. DNA concentration was quantified and checked on an Agilent Bioanalyzer chip for each PCR pool. Sequencing of cleaned PCR pools was performed on a Roche 454 FLX Genome Sequencer using Titanium chemistry at the University of Illinois.

To determine the number of MHC alleles per individual, we used the web server AmpliSAT [120] to de-multiplex samples within pools (AmpliSAS), cluster amplicon sequences within individuals, and filter individual sequences. Because duplication of the MHC-DRB gene is rare in ruminants and has not been seen in Odocoileinae, we predicted a single expressed copy of the gene [21, 55, 58, 69, 70, 72, 121]. However, to accommodate possible gene duplication in mule deer, we set the maximum number of alleles per individual to four. Minimum amplicon depth was set to 100 to remove potential artefacts and samples with low reads. We selected the degree of change (DOC) criterion filtering parameter to estimate the number of true alleles based on sequencing depth [122]. All other parameters were set to the default settings. Data from individuals was merged into a single file using AmpliCOMBINE within AmpliSAT. We aligned and translated sequences into amino acids in MEGA7 [123] and no stop codons were observed in any samples.

MHC phylogeny

We constructed a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree using IQ-TREE (v2.1.2, [124]) to visualize evolutionary relationships between our mule deer MHC alleles and other cervid MHC alleles. We used ModelFinder [125] as implemented within IQ-TREE to determine the best substitution model based on Bayesian Information Criteria. Branch support was assessed using 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (UFBoot2 [126]), using the F81+F+I+G4 model in IQ-TREE. We visualized the phylogeny with FigTree (v1.4.4). The phylogeny contains the 250 bp MHC-DRB exon 2 sequences from the 31 new mule deer alleles generated in this study, the 30 MHC DRB alleles previously described in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), and MHC DRB sequences from five outgroup species within Cervidae [moose (Alces alces, roe deer (Capreolus capreolus); elk (red deer, Cervus elaphus); sika deer (Cervus nippon); and caribou (reindeer, Rangier tarandus); Table 3]. The tree was rooted with an orthologous cattle DRB sequence (Bos taurus).

Population genetic data analysis

For each of the 16 populations, we calculated measures of genetic diversity separately for MHC and microsatellites. We used GenAlEx 6.5 [128] to estimate observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosity, total number of alleles (A), and number of private alleles (AP), and HP-Rare [129] to calculate allelic richness (AR) and private allele richness (APR). We tested for deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) in GenAlEx, employing a false discovery rate correction for multiple tests [130]. To explore the genetic structure and connectivity of populations at both locus types, we used STRUCTURE software on the microsatellite and the MHC datasets. We ran five iterations at each K for K = 1 to K = 16 with 50,000 burn-ins and 500,000 iterations, and correlated allele frequencies. We then used individual genotypes in an unsupervised Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC [131]), using the adegenet package v2.1.0 in R [132, 133]. We also calculated genetic differentiation (Jost’s D, [134]) between pairs of populations using GenAlEx.

We used several selection and neutrality tests to investigate the influence of natural selection on MHC variation in our mule deer samples. We calculated relative frequencies of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions for dN/dS (ω) ratios using codeml in PAML 4.9j [135] which follows the Nei and Gojobori [136] method. Ratios near 1 indicate selective neutrality whereas values of ω > 1 and ω < 1 suggest positive selection and purifying selection, respectively. We calculated ω values for the entire MHC-DRB exon 2, antigen-binding sites (ABS, inferred from human HLA-DRB [137]), and non-ABS. We tested for site-specific positive selection by comparing two pairs of codon substitution models: model M1a (nearly neutral) to M2a (positive selection) and model M7 (beta) to M8 (beta plus ω) [138]. Pairwise likelihood ratio tests were used to identify codons under selection and the Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) method was used to calculate the posterior probability and determine significance of the identified codons [139]. Posterior probabilities of > 0.95 were considered supported, and codons were considered to be under positive selection if they were identified by either models M2a or M8. We also performed neutrality tests in each population, including Tajima’s D [140], Fu’s F, Fu and Li’s F* and Fu and Li’s D* using DnaSP v6.12 [141] to further investigate possible selection at the MHC locus.

To compare patterns of diversity between the putatively adaptive MHC locus and the neutral microsatellite loci, we tested for correlations between MHC- and microsatellite-based genetic diversity (allelic richness and observed heterozygosity) and differentiation (Jost’s D) using Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) and Mantel [142] tests with 999 permutations in R. We tested for isolation-by-distance (IBD) in MHC and microsatellites by conducting a Mantel test with 999 permutations between a geographic distance matrix and pairwise genetic distance matrices of Jost’s D. An absent or weak IBD correlation suggests high gene flow or selection that favors similar alleles across locations, whereas strong correlations suggest population isolation or divergent selection. We compared IBD patterns between markers with a t-test to gain additional insight into the relative importance of connectivity and selection in this system.

Environmental analysis

To investigate the indirect role of environmental variation on pathogen load and thus MHC evolution, we examined the relationship between population-level genetic diversity and latitude, elevation, and climatic variables for MHC and microsatellites. Under pathogen-mediated selection, a strong relationship would be predicted where pathogen diversity, physiology, growth, and/or infectivity is tightly coupled to environmental variables. To account for variation in rates of polymorphism between marker types (average 12 alleles per locus in MHC and 5 in microsatellites) we used mean-centered allelic richness [54]. We used a linear regression to quantify the relationship between mean-centered allelic richness and latitude. To quantify environmental influences on genetic diversity, we used redundancy analysis (RDA, [143]). RDA is a multivariate ordination method which can help detect genotype-environment associations (GEAs) and loci under selection. We used latitude (Lat), longitude (long), elevation (elev), and 15 bioclimatic variables for each population obtained from the ClimateWNA database (www.climateWNA.com, [144]) from the years 1981 to 2010. The bioclimatic variables included mean annual temperature (MAT), mean warmest month temperature, mean coldest month temperature, temperature difference between warmest month and coldest month (TD, or seasonality), mean annual precipitation (MAP), annual heat-moisture index [(temperature + 10)/(precipitation/1000)], mean annual relative humidity (RH), and mean temperature and precipitation for each season (winter, spring, summer, and fall). We also obtained elevation for each population from www.mapcoordinates.net/en. We tested for multicollinearity between variables using Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) and removed correlated variables (|r|> 0.8). We ran RDA analyses for microsatellites using allelic richness at each locus, and for MHC using allele frequencies per population. We plotted the RDA axes using the vegan package v2.5-7 in R [145] to visualize how environmental predictors explained the genetic variation at each locus. F statistics were used to test the significance of the full RDA models and each constrained axis.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in the current study are included in Additional file 2. Novel sequences for this project have been deposited in GenBank (MZ450871-MZ450901).

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Number of alleles

- ABS:

-

Antigen-binding site

- Ap:

-

Number of private alleles

- Apr:

-

Private allelic richness

- Ar:

-

Allelic richness

- BEB:

-

Bayes Empirical Bayes

- DAPC:

-

Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components

- dN:

-

Rate of nonsynonymous substitutions

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DOC:

-

Degree of change

- dS:

-

Rate of synonymous substitutions

- elev:

-

Elevation

- GEA:

-

Genotype-Environment Associations

- He:

-

Expected heterozygosity

- HLA:

-

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- Ho:

-

Observed heterozygosity

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium

- IBD:

-

Isolation by distance

- Lat:

-

Latitude

- Long:

-

Longitude

- MAP:

-

Mean annual precipitation

- MAT:

-

Mean annual temperature

- MHC:

-

Major histocompatibility complex

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- RDA:

-

Redundancy analysis

- RH:

-

Relative humidity

- TD:

-

Temperature difference between warmest and coolest months

- VIF:

-

Variance Inflation Factors

References

Barrett R, Schluter D. Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23(1):38–44.

Lai Y, Yeung C, Omland K, Pang E, Hao Y, Liao B, Cao H, Zhang B, Yeh C, Hung C, Hung H, Yang M, Liang W, Hsu Y, Yao C, Dong L, Lin K, Li S. Standing genetic variation as the predominant source for adaptation of a songbird. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(6):2152–7.

Przeworski M, Coop G, Wall JD. The signature of positive selection on standing genetic variation. Evolution. 2005;59:2312–23.

Fisher MC, Garner TWJ, Walker SF. Global emergence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and amphibian chytridiomycosis in space, time, and host. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:291–310.

Van Rooij P, Martel A, Haesebrouck F, Pasmans F. Amphibian chytridiomycosis: a review with focus on fungus-host interactions. Vet Res. 2015;46:137.

Cryan PM, Meteyer CU, Boyles JG, Blehert DS. White-nose syndrome in bats: illuminating the darkness. BMC Biol. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-11-47.

Foley J, Clifford D, Castle K, Cryan P, Ostfeld RS. Investigating and managing the rapid emergence of white-nose syndrome, a novel, fatal, infectious disease of hibernating bats. Conserv Biol. 2011;25(2):223–31.

Yi X, Donner DM, Marquardt P, Palmer JM, Jusino MA, Frair J, Lindner DL, Latch EK. Major histocompatibility complex variation is similar in little brown bats before and after white-nose syndrome outbreak. Ecol Evol. 2020;10:10031–43.

Zukal J, Bandouchova H, Bartonicka T, Berkova H, Brack V, Brichta J, Dolinay M, Jaron KS, Kovacova V, Kovarik M, Martinkova N, Ondracek K, Rehak Z, Turner G, Pikula J. White-nose syndrome fungus: a generalist pathogen of hibernating bats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97224.

Carlson CM, Hopkins MC, Nguyen NT, Richards BJ, Walsh DP, Walter WD. Chronic wasting disease: status, science, and management. US Geological Survey, Madison; 2018.

Cullingham CI, Peery RM, Dao A, McKenzie DI, Coltman DW. Predicting the spread-risk potential of chronic wasting disease to sympatric ungulate species. Prion. 2020;14(1):56–66.

Mawdsley JR. Phylogenetic patterns suggest broad susceptibility to chronic wasting disease across Cervidae. Wildl Soc Bull. 2020;44:152–5.

Monello RJ, Galloway NL, Powers JG, Madsen-Bouterse SA, Edwards WH, Wood ME, O’Rourke KI, Wild MA. Pathogen-mediated selection in free-ranging elk populations infected by chronic wasting disease. PNAS. 2017;114(46):12208–12.

Borghans J, Beltman J, De Boer R. MHC polymorphism under host-pathogen coevolution. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:732–9.

Piertney SB, Oliver MK. The evolutionary ecology of the major histocompatibility complex. Heredity. 2006;96:7–21.

Radwan J, Babik W, Kaufman J, Lenz TL, Winternitz J. Advances in the evolutionary understanding of MHC polymorphism. Trends Genet. 2020;36(4):298–311.

Spurgin LG, Richardson DS. How pathogens drive genetic diversity: MHC, mechanisms and misunderstandings. Proc R Soc B. 2010;277(1684):979–88.

Winternitz JC, Minchey SG, Garamszegi LZ, Huang S, Stephens PR, Altizer S. Sexual selection explains more functional variation in the mammal major histocompatibility complex than parasitism. Proc R Soc B. 2013;280:20131605.

Froeschke G, Sommer S. MHC Class II DRB variability and parasite load in the striped mouse (Rhabomys pumilio) in the Southern Kalahari. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(5):1254–9.

Hosotani S, Nishita Y, Masuda R. Genetic diversity and evolution of the MHC class II DRB gene in the Japanese marten, Martes melampus (Carnivora: Mustelidae). Mamm Res. 2020;65:573–82.

Mikko S, Roed K, Schmutz S, Andersson L. Monomorphism and polymorphism at MHC DRB loci in domestic and wild ruminants. Immunol Rev. 1999;167:169–78.

Teacher AGF, Garner TWJ, Nichols RA. Evidence for directional selection at a novel major histocompatibility class I marker in wild common frogs (Rana temporaria) exposed to a viral pathogen (Ranavirus). PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4616.

Ashby B, Boots M. Multi-mode fluctuating selection in host-parasite coevolution. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:357–65.

Eizaguirre C, Lenz TL, Kalbe M, Milinski M. Rapid and adaptive evolution of MHC genes under parasite selection in experimental vertebrate populations. Nat Commun. 2012;3:621.

Ejsmond MJ, Babik W, Radwan J. MHC allele frequency distributions under parasite-driven selection: a simulation model. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:332.

Hedrick PW. What is the evidence for heterozygote advantage selection? Trends Ecol Evol. 2012;27(12):698–704.

Niskanen AK, Kennedy LJ, Ruokonen M, Kojola I, Lohi H, Isomursu M, Jansson E, Pyhajarvi T, Aspi J. Balancing selection and heterozygote advantage in major histocompatibility complex loci of the bottlenecked Finnish wolf population. Mol Ecol. 2013;23:875–89.

Bernatchez L, Landry C. MHC studies in nonmodel vertebrates: what have we learned about natural selection in 15 years? J Evol Biol. 2003;16:363–77.

Fraser B, Neff B. Parasite mediated homogenizing selection at the MHC in guppies. Genetica. 2010;138:273–8.

Quemere E, Hessenauer P, Galan M, Fernandez M, Merlet J, Chaval Y, Hewison AJM, Morellet N, Verheyden H, Gilot-Fromont E, Charbonnel N. Fluctuating pathogen-mediated selection drives the maintenance of innate immune gene polymorphism in a widespread wild ungulate. bioRxiv. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1101/458216.

Sommer S. Effects of habitat fragmentation and changes of dispersal behaviour after a recent population decline on the genetic variability of noncoding and coding DNA of a monogamous Malagasy rodent. Mol Ecol. 2003;12(10):2845–51.

Strand T, Segelbacher G, Quintela M, Xiao L, Axelsson T, Hoglund J. Can balancing selection on MHC loci counteract genetic drift in small fragmented populations of black grouse? Ecol Evol. 2012;2(2):341–53.

Ditchkoff SS, Lockmiller RL, Masters RE, Hoofer SR, Van Den Bussche RA. Major-histocompatibility-complex-associated variation in secondary sexual traits of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus): evidence for good-genes advertisement. Evolution. 2001;55(3):616–25.

Dunn PO, Bollmer JL, Freeman-Gallant CR, Whittingham LA. MHC variation is related to a sexually selected ornament, survival, and parasite resistance in common yellowthroats. Evolution. 2012;67(3):679–87.

Ivy-Israel N, Moore C, Schwartz T, Steury T, Zohdy S, Newbolt C, Ditchkoff S. Association between sexually selected traits and allelic distance in two unlinked MHC II loci in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Evol Ecol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-021-10108-x.

Moore CE. Reproductive success in white-tailed deer: using structural equation modeling to understand the causal relationships of MHC, age, and morphology. MS Thesis—Auburn University, Auburn; 2019.

Penn DJ. The scent of genetic compatibility: sexual selection and the major histocompatibility complex. Ethology. 2002;108:1–21.

Reusch TBH, Haberli MA, Aeschlimann PB, Milinski M. Female sticklebacks count alleles in a strategy of sexual selection explaining MHC polymorphism. Nature. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1038/35104547.

Whittingham LA, Freeman-Gallant CR, Taff CC, Dunn PO. Different ornaments signal male health and MHC variation in two populations of warbler. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:1584–95.

Teitelbaum CS, Huang S, Hall RJ, Altizer S. Migratory behaviour predicts greater parasite diversity in ungulates. Proc R Soc B. 2018;285:20180089.

Turner WC, Getz WM. Seasonal and demographic factors influencing gastrointestinal parasitism in ungulates of Etosha National Park. J Wildl Dis. 2010;46(4):1108–19.

Bollmer JL, Hull JM, Ernest HB, Sarasola JH, Parker PG. Reduced MHC and neutral variation in the Galapagos hawk, an island endemic. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:143.

Cai R, Shafer ABA, Laguardia A, Lin Z, Liu S, Hu D. Recombination and selection in the major histocompatibility complex of the endangered forest musk deer (Moschus berezovskii). Sci Rep. 2015;5:17285.

Eimes J, Bollmer J, Whittingham JL, Johnson JA, Van Oosterhout C, Dunn PO. Rapid loss of MHC class II variation in a bottlenecked population is explained by drift and loss of copy number variation. J Evol Biol. 2011;24:1847–56.

Elbers JP, Clostio RW, Taylor SS. Neutral genetic processes influence MHC evolution in threatened gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus). J Hered. 2017;108(5):515–23.

Peng F, Ballare KM, Woodard SH, den Haan S, Bolnick DI. What evolutionary processes maintain MHC IIβ diversity within and among populations of stickleback? Mol Ecol. 2021;00:1–13.

Taylor SS, Jenkins DA, Arcese P. Loss of MHC and neutral variation in Peary caribou: genetic drift is not mitigated by balancing selection or exacerbated by MHC allele distributions. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36748.

Cortazar-Chinarro M, Lattenkamp EZ, Meyer-Lucht Y, Luquet E, Laurila A, Hoglund J. Drift, selection, or migration? Processes affecting genetic differentiation and variation along a latitudinal gradient in an amphibian. BMC Evol Biol. 2017;17:189.

Miller H, Allendorf F, Daugherty C. Genetic diversity and differentiation at MHC genes in island populations of tuatara (Sphenodon spp.). Mol Ecol. 2010;19(18):3894–908.

Zeisset I, Beebee T. Drift rather than selection dominates MHC class II allelic diversity patterns at the biogeographical range scale in Natterjack Toads Bufo calamita. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e100176.

Ekblom R, Saether S, Jacobsson P, Fiske P, Sahlman T, Grahn M, Kalas J, Hoglund J. Spatial pattern of MHC class II variation in the great snipe (Gallinago media). Mol Ecol. 2007;16(7):1439–51.

Kyle C, Rico Y, Castillo S, Srithayakumar V, Cullingham C, White B, Pond B. Spatial patterns of neutral and functional genetic variations reveal patterns of local adaptation in raccoon (Procyon lotor) populations exposed to raccoon rabies. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(9):2287–98.

Loiseau C, Richar M, Garnier S, Chastel O, Julliard R, Zoorob R, Sorci G. Diversifying selection on MHC class I in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus). Mol Ecol. 2009;18(7):1331–40.

Bateson Z, Whittingham L, Johnson J, Dunn P. Contrasting patterns of selection and drift between two categories of immune genes in prairie-chickens. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(24):6095–106.

Kennedy L, Modrell A, Groves P, Wei Z, Single R, Happ G. Genetic diversity of the major histocompatibility complex class II in Alaskan caribou herds. Immunogenetics. 2011;00:1–11.

Arguello-Sanchez LE, Arguello JR, Garcia-Feria LM, Garcia-Sepulveda CA, Santiago-Alarcon D, Espinosa de los Monteros A. MHC class II DRB variability in wild black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra), and endangered New World primate. Anim Biodivers Conserv. 2018;41(2):389–404.

Campos JL, Posada D, Moran P. Genetic variation at MHC, mitochondrial and microsatellite loci in isolated populations of Brown trout (Salmo trutta). Conserv Genet. 2006;7:515–30.

Mikko S, Andersson L. Low major histocompatibility complex class II diversity in European and North American moose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4259–63.

Quemere E, Galan M, Cosson JF, Klein F, Aulagnier S, Gilot-Fremont E, Merlet J, Bonhomme M, Hewison AJM, Charbonnel N. Immunogenetic heterogeneity in a widespread ungulate: the European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Mol Ecol. 2015;24(15):3873–87.

Barton N. Understanding adaptation in large populations. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(6):e1000987.

Davidson WR, Hayes FA, Nettles VF, Kellogg FE. Diseases and parasites of White-tailed deer. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station. 1981.

Samuel WM, Pybus MJ, Kocan AA. Parasitic Diseases of Wild Mammals. No. Ed. 2. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 2001.

Williams ES, Barker IK. Blood-inhabiting protozoan parasites in Parasitic diseases of Wild Mammals. No. Ed. 3. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, p. 520-523. 2001.

Schaschl H, Wandeler P, Suchentrunk F, Obexer-Ruff G, Goodman SJ. Selection and recombination drive the evolution of MHC class II DRB diversity in ungulates. Heredity. 2006;97:427–37.

Latch EK, Reding D, Heffelfinger J, Alcala-Galvan C, Rhodes OE. Range-wide analysis of genetic structure in a widespread, highly mobile species (Odocoileus hemionus) reveals the importance of historical biogeography. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:3171–90.

Van den Bussche R, Ross T, Hoofer S. Genetic variation at a major histocompatibility locus within and among populations of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). J Mammal. 2002;83(1):31–9.

Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife—threats to biodiversity and human health. Science. 2000;287(5452):443–9.

Russell RE, DiRenzo GV, Szymanski JA, Alger KE, Grant EH. Principles and mechanisms of wildlife population persistence in the face of disease. Front Ecol Evol. 2020;8:344.

Ivy-Israel N, Moore C, Schwartz T, Ditchkoff S. Characterization of two MHC II genes (DOB, DRB) in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). BMC Genet. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-020-00889-5.

Van den Bussche R, Hoofer S, Lochmiller R. Characterization of Mhc-DRB allelic diversity in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) provides insight into Mhc-DRB allelic evolution within Cervidae. Immunogenetics. 1999;49:429–37.

Perez-Espona S, Goodall-Copestake WP, Savirina A, Bobovikova J, Molina-Rubio C, Perez-Barberia FJ. First assessment of MHC diversity in wild Scottish red deer populations. Eur J Wildl Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-019-1254-x.

Swarbrick PA, Schwaiger FW, Epplen JT, Buchan GS, Griffin JFT, Crawford AM. Cloning and sequencing of expressed DRB genes of the red deer (Cervus elaphus) MHC. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:1–9.

Mikko S, Lewin HA, Andersson L. A phylogenetic analysis of cattle DRB3 alleles with a deletion of codon 65. Immunogenetics. 1997;47:23–9.

Gao FY, Zhang D, Lu MX, Cao JM, Liu ZG, Ke XL, Wang M, Zhang DF, Yi MM. MHC class IIA polymorphisms and their association with resistance–susceptibility to Streptococcus agalactiae in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. J Fish Biol. 2018;93(6):1207–15.

Eimes J, Bollmer J, Dunn P, Whittingham L, Wimpee C. Mhc class II diversity and balancing selection in greater prairie-chickens. Genetica. 2010;138:265–71.

Gagnon M, Yannic G, Boyer F, Cote SD. Adult survival in migratory caribou is negatively associated with MHC functional diversity. Heredity. 2020;125:290–303.

Oliver MK, Telfer S, Piertney SB. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) heterozygote superiority to natural multi-parasite infections in the water vole (Arvicola terrestris). Proc R Soc B. 2009;276:1119–28.

Ejsmond MJ, Radwan J. MHC diversity in bottlenecked populations: a simulation model. Conserv Genet. 2011;12:129–37.

Dussex N, Alberti F, Heino MT, Olsen RA, van der Valk T, Ryman N, Laikre L, Ahlgren H, Askeyev IV, Askeyev OV, Shaymuratova DN, Askeyev AO, Doppes D, Friedrich R, Lindauer S, Rosendahl W, Aspi J, Hofreiter M, Liden K, Dalen L, Diez-del-Molino D. Moose genomes reveal past glacial demography and the origin of modern lineages. BMC Genomics. 2020;21:854.

Hundertmark KJ, Shields GF, Bowyer RT, Schwartz CC. Genetic relationships deduced from cytochrome-b sequences among moose. Alces. 2002;38:113–22.

Hundertmark KJ. Home range, dispersal and migration. In: Franzmann AW, Schwartz CC, McCabe R, editors. Ecology and management of the North American moose. 2nd ed. Boulder: University Press of Colorado; 2007. p. 303–36.

DeYoung RW, Demarais S, Honeycutt RL, Rooney AP, Gonzales RA, Gee KL. Genetic consequences of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) restoration in Mississippi. Mol Ecol. 2003;12:3237–52.

Latch EK, Heffelfinger JR, Fike JA, Rhodes OE. Species-wide phylogeography of North American mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus): cryptic glacial refugia and postglacial recolonization. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:1730–45.

Salkeld DJ, Trivedi M, Schwarzkopf L. Parasite loads are higher in the tropics: temperate to tropical variation in a single host-parasite system. Ecography. 2008;31:538–44.

Charbonnel N, Pemberton J. A long-term genetic survey of an ungulate population reveals balancing selection acting on MHC through spatial and temporal fluctuations in selection. Heredity. 2005;95:377–88.

Dionne M, Miller KM, Dodson JJ, Caron F, Bernatchez L. Clinal variation in mhc diversity with temperature: evidence for the role of host-pathogen interaction on local adaptation in Atlantic Salmon. Evolution. 2007;61(9):2154–64.

Schwensow N, Fietz J, Dausmann KH, Sommer S. Neutral versus adaptive genetic variation in parasite resistance: importance of major histocompatibility complex supertypes in a free-ranging primate. Heredity. 2007;99:265–77.

Bell G. Fluctuating selection: the perpetual renewal of adaptation in variable environments. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:87–97.

Bergland AO, Behrman EL, O’Brien KR, Schmidt PS, Petrov DA. Genomic evidence of rapid and stable adaptive oscillations over seasonal time scales in Drosophila. PLoS ONE. 2014;10(11):e1004775.

O’Connor EA, Hasselquist D, Nilsson JA, Westerdahl H, Cornwallis CK. Wetter climates select for higher immune gene diversity in resident, but not migratory, songbirds. Proc R Soc B. 2020;287:20192675.

Andreani ML, Freitas L, Ramos EKS, Nery MF. Latitudinal diversity gradient and cetaceans from the perspective of MHC genes. Immunogenetics. 2020;72:393–8.

Awadi A, Slimen HB, Smith S, Knauer F, Makni M, Suchentrunk F. Positive selection and climatic effects on MHC class II gene diversity in hares (Lepus capensis) from a steep ecological gradient. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11514.

Guernier V, Hochberg M, Guegan J. Ecology drives the worldwide distribution of human diseases. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(6):e141.

Tonteri A, Vasemagi A, Lumme J, Primmer CR. Beyond MHC: signals of elevated selection pressure on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) immune-relevant loci. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:1273–82.

Hawkins BA, Diniz-Filho AF. Latitude and geographic patterns in species richness. Ecography. 2004;27(2):268–72.

Alcaide M, Edwards S, Negro J, Serrano D, Tella J. Extensive polymorphism and geographical variation at a positively selected MHC class II B gene of the lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni). Mol Ecol. 2008;17:2652–65.

Collin H, Burri R, Comtesse F, Fumagalli L. Combining molecular evolution and environmental genomics to unravel adaptive processes of MHC class IIB diversity in European minnows (Phoxinus phoxinus). Ecol Evol. 2013;3(8):2568–85.

Sallaberry-Pincheira N, Gonzalez-Acuna D, Padilla P, Dantas GPM, Luna-Jorquera G, Frere E, Valdes-Velasquez A, Vianna JA. Contrasting patterns of selection between MHC I and II across populations of Humboldt and Magellanic penguins. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:7498–510.

Preisser W. Latitudinal gradients of parasite richness: a review and new insights from helminths of cricetid rodents. Ecography. 2019;42(7):1315–30.

Haines M, Luikart G, Amish S, Smith S, Latch E. Evidence for adaptive introgression of exons across a hybrid swarm in deer. BMC Evol Biol. 2019;19:199.

Myers WL, Foreyt WJ, Talcott PA, Evermann JF, Chang WY. Serologic, trace element, and fecal parasite survey of free-ranging, female mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in Eastern Washington, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2015;51(1):125–36.

Nonaka M, Namikawa C, Kato Y, Sasaki M, Salter-Cid LS, Flajnik MF. Major histocompatibility complex gene mapping in the amphibian Xenopus implies a primordial organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5789–91.

Ohta Y, Okamura K, McKinney EC, Bartl S, Hashimoto K, Flajnik MF. Primitive synteny of vertebrate major histocompatibility complex class I and class II genes. PNAS. 2000;97(9):4712–7.

Minias P, Bateson ZW, Whittingham LA, Johnson JA, Oyler-McCance S, Dunn PO. Contrasting evolutionary histories of MHC class I and class II loci in grouse—effects of selection and gene conversion. Heredity. 2016;116:466–76.

Minias P, Pikus E, Whittingham LA, Dunn PO. A global analysis of selection at the avian MHC. Evolution. 2018;72(6):1278–93.

Grueber CE, Jamieson IG. Primers for amplification of innate immunity toll-like receptor loci in threatened birds of the Apterygiformes, Gruiformes, Psittaciformes and Passeriformes. Conserv Genet Resour. 2013;5:1043–7.

Tschirren B, Andersson M, Scherman K, Westerdahl H, Mittle PRE, Raberg L. Polymorphisms at the innate immune receptor TLR2 are associated with Borrelia infection in a wild rodent population. Proc R Soc B. 2013;280:20130364.

Turner SJ, Rossjohn J. αβ T cell receptors come out swinging. Immunity. 2011;35(5):660–2.

O’Connor EA, Westerdahl H. Trade-offs in expressed major histocompatibility complex diversity seen on a macroevolutionary scale among songbirds. Evolution. 2021;75(5):1061–9.

Bozkaya F, Kuss AW, Geldermann H. DNA variants of the MHC show location-specific convergence between sheep, goat and cattle. Small Rumin Res. 2007;70:174–82.

Eimes J, Townsend AK, Sepil I, Nishiumi I, Satta Y. Patterns of evolution in MHC class II genes of crows (Corvus) suggest trans-species polymorphism. PeerJ. 2015;3:e853.

Lenz TL, Eizaguirre C, Kalbe M, Milinski M. Evaluating patterns of convergent evolution and trans-species polymorphism AT MHC immunogenes in two sympatric stickleback species. Evolution. 2013;67(8):2400–12.

Ballingall KT, Rocchi MS, McKeeer DJ, Wright F. Trans-species polymorphism and selection in the MHC class II DRA genes of domestic sheep. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11402.

Klein J. Origin of major histocompatibility complex polymorphism: the trans-species hypothesis. Hum Immunol. 1987;19(3):155–62.

Stephens PR, Pappalardo P, Huang S, Byers JE, Farrell MJ, Gehman A, Ghai RR, Haas SE, Han B, Park AW, Schmidt JP, Altizer S, Ezenwa VO, Nunn CL. Global mammal parasite database version 2.0. Ecology. 2017;98(5):1476.

Latch EK, Kierepka E, Heffelfinger J, Rhodes OE. Hybrid swarm between divergent lineages of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). Mol Ecol. 2011;20:5265–79.

Latch EK, Amann RP, Jacobson JP, Rhodes OE. Competing hypotheses for the etiology of cryptorchidism in Sitka black-tailed deer: an evaluation of evolutionary alternatives. Anim Conserv. 2008;11:234–46.

Latch EK, Scognamillo DG, Fike JA, Chamberlain MB, Rhodes OE. Deciphering ecological barriers to North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) gene flow in the Louisiana landscape. J Hered. 2008;99:265–74.

Sigurdardottir S, Borsch C, Gustafsson K, Andersson L. Cloning and sequence analysis of 14 DRB alleles of the bovine major histocompatibility complex by using the polymerase chain reaction. Anim Genet. 1991;22:199–209.

Sebastian A, Herdegen M, Migalska M, Radwan J. AMPLISAS: a web server for multilocus genotyping using next-generation amplicon sequencing data. Mol Ecol. 2016;16:498–510.

Dutia BM, McConnell I, Ballingall KT, Keating P, Hopkins J. Evidence for the expression of two distinct MHC class II DRβ like molecules in the sheep. Anim Genet. 1994;25(4):235–41.

Lighten J, Van Oosterhout C, Paterson I, McMullan M, Bentzen P. Ultra-deep Illumina sequencing accurately identifies MHC class IIb alleles and provides evidence for copy number variation in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata). Mol Ecol. 2014;14:753–67.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4.

Nguyen L, Schmidt H, von Haeseler A, Minh B. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268–74.

Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh B, Wong T, von Haeseler A, Jermiin L. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14:587–9.

Hoang DT, Chernomor O, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(2):518–22.

Xu A, van Eijk MJ, Park C, Lewin HA. Polymorphism in BoLA-DRB3 exon 2 correlates with resistance to persistent lymphocytosis caused by bovine leukemia virus. J Immunol. 1993;151(12):6977–85.

Peakall R, Smouse P. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(19):2537–9.

Kalinowski ST. HP-Rare 1.0: a computer program for performing rarefaction on measures of allelic richness. Mol Ecol Notes. 2005;5:187–9.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57(1):289–300.

Jombart T, Devillard S, Balloux F. Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet. 2010;11:94.

Jombart T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinform Appl. 2008;24(11):1403–5.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2020. https://www.R-roject.org/.

Jost L. G(ST) and its relatives do not measure differentiation. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:4015–26.

Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–91.

Nei M, Gojobori T. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3(5):418–26.

Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Sequence variability analysis of human class I and class II MHC molecules: functional and structural correlates of amino acid polymorphisms. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:623–41.

Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen A. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–49.

Yang Z, Wong WSW, Nielsen R. Bayes Empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–18.

Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95.

Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sanchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, Sanchez-Garcia A. DnaSPv6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–302.

Mantel N. Ranking procedures for arbitrarily restricted observation. Biometrics. 1967;23(1):65–78.

Forester BR, Lasky JR, Wagner HH, Urban DL. Comparing methods for detecting multilocus adaptation with multivariate genotype-environment associations. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2215–33.

Wang T, Hamann A, Spittlehouse DL, Murdock TQ. ClimateWNA—high-resolution spatial climate data for Western North America. J Appl Meteorol Climatol. 2012;51:16–29.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O'Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wegner H. vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.5-7. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support provided by James R. Heffelfinger, Arizona Game and Fish Department. Samples from the entire range were collected by more than 150 volunteers, which, regrettably, are too numerous to mention individually. James Speers at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center was instrumental in generating the sequencing data. Dr. Zachary Bateson provided analytical assistance. We appreciate the helpful comments provided by anonymous reviewers on this manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Graduate School and the UWM Office of Undergraduate Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RC analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. BS performed the laboratory work and generated the sequence data. RG contributed to data analysis and interpretation. MH contributed to data analysis and curation and provided analysis tools. EKL generated the microsatellite data, acquired funding, and supervised the project. All authors contributed to manuscript review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Sequencing depth and allele calls. Figure S2. Alignment of MHC amino acid sequences. Figure S3. STRUCTURE results. Table S1. MHC allele frequencies and sequencing results by population. Table S2. Microsatellite allele frequencies by population.

Additional file 2.

Sample details, microsatellite and MHC genotypes per individual.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, R.M., Suttner, B., Giglio, R.M. et al. Selection and demography drive range-wide patterns of MHC-DRB variation in mule deer. BMC Ecol Evo 22, 42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01998-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01998-8