Abstract

Background

Organismal fitness can be determined at early life-stages, but phenotypic variation at early life-stages is rarely considered in studies on evolutionary diversification. The trophic apparatus has been shown to contribute to sympatric resource-mediated divergence in several taxa. However, processes underlying diversification in trophic traits are poorly understood. Using phenotypically variable Icelandic Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus), we reared offspring from multiple families under standardized laboratory conditions and tested to what extent family (i.e. direct genetic and maternal effects) contributes to offspring morphology at hatching (H) and first feeding (FF). To understand the underlying mechanisms behind early life-stage variation in morphology, we examined how craniofacial shape varied according to family, offspring size, egg size and candidate gene expression.

Results

Craniofacial shape (i.e. the Meckel’s cartilage and hyoid arch) was more variable between families than within families both across and within developmental stages. Differences in craniofacial morphology between developmental stages correlated with offspring size, whilst within developmental stages only shape at FF correlated with offspring size, as well as female mean egg size. Larger offspring and offspring from females with larger eggs consistently had a wider hyoid arch and contracted Meckel’s cartilage in comparison to smaller offspring.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence for family-level variation in early life-stage trophic morphology, indicating the potential for parental effects to facilitate resource polymorphism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Phenotypic variation is ubiquitous in natural populations, yet many of the processes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation are still little understood. The fitness consequences of phenotypic variation can be strong at early-life stages [1,2,3,4,5], yet early life-stage phenotypic variation is rarely considered in studies of evolutionary diversification. Fishes are the most species-rich clade of vertebrates, and offer an array of skull and jaw morphologies that reflect their ecological specialization [6,7,8]. One of the most famed examples of evolutionary diversification are the African rift-lake cichlids where adaptive radiation in feeding morphology has contributed to their rapid diversification [9,10,11,12]. If such variation in trophic structures is expressed already early in life, then individuals may be able to specialize on alternative resources, increasing phenotypic variation within a population [13], and thus providing fuel for natural selection. It is hypothesized that individual specialization to different diets may reduce intraspecific competition [14, 15], which can facilitate divergence of trophic morphology and the evolution of resource polymorphism (i.e. discrete intraspecific morphs that have diverged upon different resources) [16,17,18,19]. Ultimately, resource polymorphism may facilitate sympatric speciation [19,20,21] and provide valuable insight into evolutionary processes underlying diversification.

Glacial retreats following the last ice age have provided a window of opportunity to examine such processes in polymorphic Northern freshwater fishes, whereby their degree of phenotypic divergence often varies between different systems [22]. However, what initially generates phenotypic variation within populations is still poorly understood. By focusing on individual variation at very early life-stages (i.e. prior to the onset of feeding), this study aims to understand which factors promote variability in trophic morphology within a single population of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus), and potentially shed light on the mechanisms underlying early stages of evolutionary diversification.

The extent of intraspecific divergence can be biased along both genetic and developmental lines of least resistance [23, 24], expanding upon existing phenotypic variation, but limited by available resources [25]. Importantly, the phenotype is often more malleable early in the development than later in life [23], because gene expression is more dynamic [26,27,28,29], can influence developmental trajectories (discussed in: [29,30,31]) and traits are not yet fixed. Studying early life-stage gene expression jointly with morphology can thus provide insight into developmental processes initiating phenotypic variation (e.g. [32]). Gene expression patterns have been linked to phenotypic divergence between different morphs in several taxa [31,32,33,34,35,36], but early life-stage variation in gene expression and morphology within morphs have been less well-studied. Particularly at early life-stages, variation in gene expression and morphology can be influenced by parental effects, for instance as differential distribution of maternal resources (i.e. egg size) which, in turn, can contribute to trophic specialization [33, 37, 38].

Parental effects – when the phenotype or performance of an individual is affected by the phenotype or environment of its parents [39] – are a common source of phenotypic variation at early life-stages [40, 41] and play a crucial role during early development [39]. The extent to which offspring phenotype is influenced by maternal effects can depend on multiple maternally transmitted factors such as yolk, mRNA transcripts or other cytoplasmic factors packaged in the egg by the mother during oogenesis [16, 41]. Studying early developmental stages can not only reveal the impact that parental effects might have on phenotypic variation of their offspring, but also gives insight into how phenotypes vary before exposure to external sources of environmental variation, such as diet. Importantly, variation in trophic morphology in developing embryos may reflect genetic and non-genetic parental effects and affect fitness of individuals when they start independent feeding.

The high propensity of Arctic charr for intraspecific diversity makes this species well suited for studying mechanisms that promote and/or precede the evolutionary origins of phenotypic diversity, especially associated with trophic polymorphism [42, 43]. Although several studies have examined associations between parental effects, gene expression and phenotypic variation between established morphs (see references above), which are sometimes visible at early-life stages [43, 44], there are relatively few (if any) studies examining such associations within a morph, or a population. Here we study a single morph of Arctic charr (Vatnshlíðarvatn brown [45];) to examine the association between early life-stage phenotypic variation (size and morphology), family (incl. Direct genetic and/or maternal effects) and gene expression at hatching (H) and first feeding (FF). Previously in this morph, we showed that early life-stage gene expression is very dynamic at early life-stages and that there is a correlation between offspring size and relative expression of two genes related to skeletal development and growth [29]: Sgk1 showed a linear relationship with individual size, having higher expression in larger embryos at H, whereas Star was non-linear in relation to individual size. Using highly diverged benthic and pelagic morphs of Arctic charr, a previous study found that both of these genes – Sgk1 and Star showed differential expression between the two morphs [33].

Here we combine our previous findings on dynamic early life-stage gene expression [29] with patterns of craniofacial morphology in the Vatnshlíðarvatn brown morph. We use acid-free double staining of cartilage and bone, coupled with geometric morphometrics, to test whether individuals from different families develop differently (i.e. resulting in different trophic morphologies at H and FF). We study variation among seven families, with family effects reflecting a combination of direct genetic and non-genetic parental effects. We studied eight growth-related genes (chosen from the literature based on their involvement during early development, [29]) and six genes related to skeletogenesis (based on findings in a previous study, [32]). Combining this previously collected gene expression data [29] with data on offspring morphology, we test the following predictions: 1) if there are genetic and/or parental effects in shape at early life-stages, we should see differences among families in craniofacial features; 2) if early life-stage phenotypic variation is related to genes involved in growth and skeletogenesis of trophic structures, offspring craniofacial shape should covary with the expression of the chosen candidate genes, and 3) if maternal investment (i.e. egg size) influences early life-stage phenotypes, female mean egg size and/or individual offspring size should correlate with offspring morphology.

Results

Craniofacial shape

Measurement errors from digital images of morphology (Fig. 1) were calculated for replicates using the Procrustes ANOVA. Variation due to placement accounted for 6% at H and 10% at FF, whilst variation due to digitizing error was 3 and 6% at H and FF, respectively (Table S1). Once variation due to measurement error, as well as directional and fluctuating asymmetry, was accounted for, variation among individuals accounted for 73 and 70% of variation at H and FF, respectively (Table S1).

Craniofacial structures at two early life-stages (hatching and first feeding) in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). Ventral craniofacial bones and cartilages at hatching (a) and first feeding (b) of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) embryos from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn. EP, ethmoid plate; MC, Meckel’s cartilage; HH, hypohyal; CH, ceratohyal; BSR, branchiostegal rays; PQ, palatoquadrate. We refer to the combination of the HH, CH and BSR as the hyoid arch (HA). For timing and sequence of occurrence of these structures in Arctic charr see Kapralova et al. (2015). The 71 homologous landmarks used to quantify craniofacial shape change at hatching (c) and first feeding (d) can be divided into 17 fixed (larger dots) and 54 semi-landmarks (smaller dots). † BSR themselves were not considered for analyses but their attachment was incorporated as part of the HA

Morphological variation was analysed using geometric morphometrics, with craniofacial shape encompassing the hyoid arch and Meckel’s cartilage using 17 fixed 54 sliding semi-landmarks (Fig. 1). Only final models are shown (Table 1). Due to lack of any differences between the results of models with and without the effect of individual size (Table 1), we only report findings for those models with size included. Model 1 tested the effect of family and developmental stage on craniofacial shape. Family explained 40% of the variation in the craniofacial shape (Z6, 92 = 5.56, R2 = 0.40, P = 0.001), with no statistically significant effect of developmental stage (Z1, 92 = 0.51, R2 = 0.01, P = 0.313; Table 1). There were two clusters clearly visible in the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) plot (Fig. 2a; Fig. S1 with the effect of size removed), with PC1 explaining 69.7% and PC2 explaining 16.1% of variation in shape (Fig. 2a). For Model 1b, the correlation of PC1 and PC2 with offspring size and family within the same model resulted in a non-significant family effect, indicating that family effects were largely due to covariation with offspring size. As such, offspring size and family were tested separately alongside developmental stage. PC1 was correlated with both offspring size (Z1, 92 = 1.16, R2 = 0.04, P = 0.045) and family identity (Z6, 92 = 4.00, R2 = 0.43, P = 0.001), but not developmental stage (Table 1). However, when examining the relationship between offspring size and PC1 (Fig. 2b), offspring at H were clearly smaller and had a more-narrow hyoid arch than offspring at FF, which had a wider hyoid arch and contracted Meckel’s cartilage. When investigating family differences, those families that differed at H were not the same as those that differed at FF, and half-sib families (females 25, 28 and 31) did not cluster together away from full-sib families (Fig. 2a). All individuals from families 30 and 31 cluster exclusively in shape space, as well as most offspring from family 28 (with the exception of one individual). These three families showed a significantly wider hyoid arch and overall more contracted craniofacial shape along PC1 compared to the other families (P < 0.001, according to least square means; Fig. 3a), whilst for PC2 the same three families showed a more elongated phenotype in both the Meckel’s cartilage and hyoid arch (P < 0.01; Fig. 3b).

Family variation in craniofacial shape in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) at hatching and first-feeding. a Principal components analysis (PCA) plot showing craniofacial shape variation across families, and (b) the correlation between PC1 and offspring size (standard length, mm), at both hatching and first feeding in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn. A total of 71 landmarks were used (see Fig. 1) and resulting deformation grids, with a 2x magnification, are presented at the extremes of both axes to facilitate the interpretation of shape change. Family identity (N offspring 5–9) is represented by different symbols

Mean family differences in offspring craniofacial shape in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). Principal co-ordinate 1 (PC1) from Fig. 2a explains the maximal variation in early life-stage craniofacial shape. a PC1 correlated against family identity (Z6, 92 = 4.00, R2 = 0.43, P = 0.001), with families 28, 30 and 31 differing from all other families based on least square means (P < 0.001), and b) PC2 and family (Z6, 92 = 4.70, R2 = 0.53, P = 0.001) with families 28, 30 and 31 also differing from all other families (P < 0.01). Deformation grids are presented at the extremes of both axes to facilitate the interpretation of shape change with a ×2 magnification

Model 2 investigated whether family mean egg size influenced craniofacial shape across developmental stages, both of which were found to have no effect (Table 1). For Model 3, we examined the effect of offspring size and family within each developmental stage. For H, offspring size and family were not confounded and could therefore be included within the same model, with family explaining 37% of variation in the shape of the hyoid arch and Meckel’s cartilage at H (Z6, 39 = 2.91, R2 = 0.37, P = 0.003), and no effect of offspring size (Table 1). Offspring size and family identity were confounded at FF and were therefore tested separately. Family explained 50% of the variation in craniofacial shape at FF (Z6, 52 = 4.66, R2 = 0.50, P = 0.001), whilst only 1% was due to offspring size 1% (Z1, 52 = 2.33, R2 = 0.10, P = 0.008), with larger offspring having a wider hyoid arch and a more contracted Meckel’s cartilage than smaller offspring (Fig. 4a).

Relationship between craniofacial shape, offspring size and egg size in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) at first feeding. Procrustes regression of craniofacial shape of offspring at first feeding on: a) individual offspring size (standard length, mm); and b) mean female egg size (diameter, mm). Deformation grids at the extremes of both axes represent the amount of shape change according to offspring/egg size, with three-fold magnification

Our final model, Model 4, examined whether there was a relationship between female mean egg size and craniofacial shape within each developmental stage. Only mean egg size at FF had a weak correlation with craniofacial shape (Z1, 52 = 2.21, R2 = 0.10, P = 0.014), the general pattern of which seems to show that offspring from females that produce larger eggs tend to have a wider hyoid arch and more contracted Meckel’s cartilage than those from females that produce smaller eggs (Fig. 4b).

Covariance between gene expression and craniofacial shape

Variation between individuals/family in relative gene expression levels can be found in [29], where all genes showed dynamic expression patterns across post-fertilization, eyed stage, H and FF. To briefly summarize, Mmp9 – a gene involved in osteogenesis – had the highest expression at H stage, whilst the only genes that had expression levels correlated with offspring size at H, were Star and Sgk1. Three genes involved in bone remodeling were found to increase at the onset of FF (Ets2, Sparc and Timp2), whilst there was a gradual increase throughout development for Ctsk and Mmp9, both of which play a role in ossification. The technical duplicates/per biological sample gave highly similar values as indicated by a very high correlation between the two technical replicates (r = 0.996, P < 0.0001, N = 1776; Fig. S2).

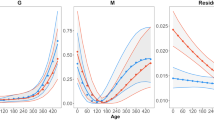

Craniofacial shape and relative gene expression for both growth and skeletogenic genes did not covary at either H or FF stage (Fig. 5; Table S2; Fig. S3 for size-free shapes). Despite this lack of covariance, we demonstrate the loadings of genes that have driven divergence in gene expression between families towards the positive (green arrows) and negative (red arrows) extremes of the PC axis in Fig. 5 (see Fig. S4 for individual data). For gene expression only, families 18 and 30 cluster away from other families at both H and FF. Whereas, for craniofacial shape, families 28, 30 and 31 cluster together at H and FF.

Craniofacial shape and gene expression in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) embryos at hatching and first feeding. Principal components analysis (PCA) plots showing both relative gene expression (for growth and skeletal related genes, modified [29]) and ventral craniofacial shape variation attributed to family in the brown Arctic charr morph from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn, at a) hatching (H), and b) first feeding (FF), with the effect of offspring size included (see Fig. S2 for PCA without the effect of size). Coloured shapes and associated standard error bars correspond to mean shape of offspring within a family. For gene expression only, green and red arrows show those genes indicated with the highest PCA loadings at the positive (green) and negative (red) extremes of the PC axes, with the top three genes (where applicable) listed from the highest to lowest loadings. Deformation grids at the extremes of both axes represent the amount of shape change, with two-fold magnification

Discussion

This study found the effect of family in the “brown” Arctic charr morph from Lake Vatnshlíðarvatn to be a major source of early morphological variation in offspring craniofacial shape (i.e. the Meckel’s cartilage and hyoid arch) throughout early development. There was no evidence for covariance between craniofacial shape and relative expression of genes related to growth and skeletogenesis. Although developmental stage was not found to be significant, when examining the relationship between offspring size and PC1 of craniofacial shape, offspring at H were clearly smaller and have a more-narrow hyoid arch than offspring at FF (Fig. 2b). Within each developmental stage, only the craniofacial shape of offspring at FF correlated with offspring size and female mean egg size, with larger offspring and offspring from females with larger eggs having a wider hyoid arch and more contracted Meckel’s cartilage than smaller offspring and offspring from females with smaller eggs (Fig. 4). Understanding the way in which variation in structures associated with feeding during early development is generated, and whether such variation can promote craniofacial divergence, may shed light upon the possible mechanisms and processes involved in the early origins of evolutionary diversification.

Family effects on craniofacial shape

Few studies have examined differences in morphology among families, despite their importance in creating variation and providing opportunities for the establishment of individual specialization, an important prelude to the evolution of resource polymorphism [13, 25]. Dietary specialization can often promote divergence of multiple ecologically distinct morphs, resulting from a process that occurs along a continuum of increasingly discrete variation: ranging from individuals that specialize upon different resources, to discrete resource morphs [13]. However, the source of this variation is less well-understood. This study found that craniofacial morphology of a single morph of Arctic charr was more variable between families than within families, with family differences seen in the hyoid arch and Meckel’s cartilage (Fig. 3). The involvement of the hyoid arch in the support and extension of the jaw suggests that offspring from different families may have the potential to differ in their efficiency for feeding on different types of prey [46, 47]. The differential ability to consume certain prey types can ultimately promote trophic divergence and resource polymorphism given the availability of alternate resources [48]. The hyoid arch is also involved in the respiratory cycle [49], whereby variation in its shape may indicate adaptive differences in respiratory needs. For example, benthic lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) from hypoxic benthic environments have larger gills, whilst pelagic planktivorous morphs tend to have larger gill lamellae surface areas [50, 51], each of which might correlate with a wider or a narrower hyoid arch, respectively. These family differences therefore represent an important source of variation to consider for the evolution of resource polymorphisms, especially given the results from this study which demonstrate the strong influence of family on offspring that have been reared in common-garden conditions. Understanding whether similar family differences are seen in offspring in the wild, and the extent to which their fine-scale phenotypic variation interacts with environmental conditions, will determine the importance of family differences in providing the initial variation for intraspecific diversification to occur.

Developmental stage differences

In general, fishes undergo both morphological and ecological changes during early life-stages due to changes in functional or structural requirements [47, 52]. Using ventral views of Arctic charr heads only, we found no differences in craniofacial shape due to developmental stage alone (Table 1), but offspring at H were smaller and had a more-narrow hyoid arch than those larger FF offspring (Fig. 2b). Few studies examine craniofacial shape differences within a single population, and instead focus of differences between morphs and/or species [33, 53,54,55]. Such studies may miss any differences between individuals, a potential source of phenotypic variation that might promote divergence in the wild. Our study demonstrates the potential of offspring size for driving inter-individual differences in the studied craniofacial shape structures across development, particularly in different females. Future studies examining internal craniofacial shape variation between individuals should increase the number of landmarks, but most importantly characterise craniofacial development in 3D, capturing ventral, dorsal and lateral changes in morphology (e.g. reviewed in Hallgrimsson et al. [56]). Such an approach will increase the likelihood of detecting fine-scale variation in the shape of embryos and fish larvae and may further reveal how the head is shaped over both developmental and evolutionary time.

Influence of gene expression on craniofacial shape

Phenotypic variation is often the result of changes in gene expression levels in response to environmental conditions, which has the potential to enhance evolutionary divergence when exposed to natural selection [57,58,59]. Although such differences may not always be apparent at the phenotypic level, analysis of gene expression provides an opportunity to uncover hidden phenotypes that may later become of ecological relevance [60]. Here we found no evidence to suggest that there is any covariance between relative expression of genes related to growth and skeletogenesis and morphology. Such lack of covariance might be a result of a time lag between the expression of certain genes and their translation into offspring phenotype. How and when certain genes are expressed and translated into phenotypic differences is uncertain, and may occur either much earlier or much later in development [26, 61]. This study was also designed to eliminate plastic responses to the environment during early development, therefore any fine-scale variation in feeding structures that would otherwise be enhanced during the feedback between morphology, food, habitat choice and their interaction with gene expression [62], would not be detected.

Effects of individual offspring size and mean female egg size on offspring morphology

Our results show that craniofacial morphology was correlated with individual offspring size (standard length) and mean egg size (diameter) per female at FF only, with larger offspring and offspring from females with larger eggs having a wider hyoid arch than smaller offspring (Fig. 4; Table 1). The influence of a maternally-mediated trait (egg size) on trophic morphology at FF can potentially have an impact on what diet is available to her offspring [63]. Furthermore, offspring-size related morphological differences in trophic structures can influence what food resources are available to offspring with more narrow or wider trophic structures (from smaller or larger offspring, respectively: Fig. 4), thus influencing trophic specialisation - a major driver of morphological divergence [7, 64]. However, such findings are weak and also confounded with family effects, with offspring from different families also differing in size. Nevertheless, this study highlights the potential role that offspring size and egg size may play in promoting intraspecific diversification,

Conclusion

Variability in trophic structures have the potential to restrict what food resources are available to offspring when they start feeding, yet our understanding of what generates this initial variation is incomplete. Here we demonstrate family differences in the shape of feeding and respiratory structures that have been linked to the evolutionary divergence of sympatric morphs [43, 51, 65, 66]. Variation in feeding structures during FF may facilitate divergence in resource use in those habitats where intraspecific competition is high, and alternate resources are available [14]. It is this fine-scale variation in feeding structures that has the potential to elicit initial divergence in diet, which may then be further emphasised through plasticity, and possibly the generation of discrete resource-morphs [19, 67,68,69].

Our understanding of the mechanisms and processes forming and maintaining biodiversity are limited, despite anthropogenic effects being one of the major underlying causes for the dramatic loss in todays’ biodiversity [70, 71]. Studies documenting phenotypic and genetic differences in morphs or populations that differ along a gradient of evolutionary diversification are needed to be able to advance our understanding of mechanisms that may promote or precede the evolutionary origins of biodiversity.

Methods

Study system

We used Arctic charr of the so called ‘brown’ morph from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn, Iceland (65°51´693 N, − 19°63′ 536 W). Vatnshlíðarvatn is a physically simple, small (70 ha) and shallow (average depth 2–3 m) lake [45]. Arctic charr is the only fish species in the lake and has diverged into two weakly divergent morphs (silver and brown [45, 72];). The brown morph shows extensive variation in egg size and egg diameter, and standard length of embryos at H and FF are strongly correlated (N = 12 families, H: R2 = 0.96, N offspring = 201, FF: R2 = 0.97, N offspring = 168; both P < 0.001, Leblanc et al. unpublished data).

The clutches and rearing protocols used in this study are described in [29]. In short, mature females (N = 7) and males (N = 5) were caught using gill nets in September 2014. Fertilised eggs were allowed to water-harden before transport. Each female was mated to a single male (i.e. full sib families), with a subset of (N = 3) females sharing the same male (i.e. half-sib families). This design causes variation in the relatedness of offspring and does not allow us to fully disentangle direct genetic from maternal effects but was used to minimize unsuccessful crosses. We henceforth use the term ‘family effects’. All adults were euthanized by lethal cranial concussion in the field after stripping and before transport back to Verið aquaculture facilities. Age of females was estimated by reading otoliths, as described by Tsinganis [73].

Fish were grown under the ethics permit of Verið aquaculture station and in accordance with Icelandic law. Experiments in this study were conducted within the ethical framework of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) as follows: 1) alternatives to the experimental procedures carried out by this research study were not available and thus the use of fish in this study was considered essential; 2) only the minimal number of fish required for the experiments were used, and all experiments were conducted on early-life stages and ended prior to independent feeding; and 3) animal welfare levels were high as experiments were conducted in an experienced aquaculture station with excellent expertise in fish husbandry practices.

Embryos were reared in the laboratory in darkness in mesh cages in a shelf incubator system with a constant flow of 95% recycled water, at a temperature of 3.5–4.5 °C. Before eye stage, a subset of at least 15 eggs were measured per family to determine mean family egg size. Developmental timing was tracked with an accumulative temperature estimate (degree days, DD [74];). Embryos were randomly collected at: 1) H, when individuals have emerged from the egg but still rely on nutrition from the yolk sac (at 461 ± 3.11 DD); and 2) FF, when individuals begin feeding (at 658 ± 12.58 DD, see Table 2 for sample summary). Samples for the gene expression (N = 82) and craniofacial shape (N = 94) analyses were collected at the same time for each family (Table 2). All embryos were euthanized using 600 ppm of 2-phenoxyethanol [75], a widely approved method [76]. All individuals (eggs, or left-side of H and FF embryos) were digitally photographed (Canon EOS 650D) with a mm scale, and eggs measured four times each to obtain average diameter as a measure of egg size, and once for measurement of standard length, SL (for H and FF stages [77];), to the nearest 0.01 mm, using the program Fiji [78].

Gene expression data collection

Gene expression data was taken from Beck et al. [29], which uses offspring from the same dataset to characterise inter-individual variation in the expression of genes related to growth and skeletogenesis. A candidate gene approach using genes found to exhibit expression differences due to either family, developmental stage or offspring size in a previous study, was selected over an analysis of the whole transcriptome in order to maximise the number of individuals per family (Beck et al., in prep. [79];). Briefly, a total of 14 candidate genes were chosen: six target genes involved in promoting trophic skeletogenesis (Timp2, Ets2, Sparc, Ctsk, Mmp2 and Mmp9) [80] and display differential expression in divergent Arctic charr morphs from lake Þingvallavatn [33]; whilst the remaining eight candidate genes (Star, Igf1, Igf2, Gr, Mtor, Sgk1, Rictor and Ghr1) were chosen using a literature search based on evidence of their involvement in promoting growth, especially during early embryonic development [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89].

Total RNA was extracted from the whole embryo at H using TRI reagent (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) after homogenizing tissues in the Bead Beater (Biospec). The same RNA extraction methods were applied to offspring at FF. However, due to their larger size, individuals were decapitated behind the pectoral fin and only the RNA extracted from the head was included in this study as most of the phenotypic variation in Arctic charr is related to trophic morphology. As in Beck et al. [29], RNA was precipitated using isopropanol, washed with ethanol and air-dried. The RNA pellet was resuspended in RNase-free water and treated with DNase I (New England, Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) to remove any contaminating DNA. A subset of extracted RNAs were electrophoresed on agarose gels to test RNA quality. Single stranded cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA, using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was consequently diluted in nuclease-free water in preparation for qPCR.

Primers [29] were designed using an assembled Arctic charr transcriptome [90] and exon boundaries mapped to Salmo salar orthologs from the salmonid species database [91]. Primers spanned at least one exon boundary and were selected based upon their short amplicon size (< 250 bp). RT-qPCR was performed on 96-well PCR plates on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using 2x Fermentas Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), with a final reaction volume of 10 μl. For family-level variation we had 4–8 individuals (replicates) per family, and a total of 7 families that represent biological replicates. Each biological sample was run in technical duplicates with a non-template control in each run for each gene. Primer efficiencies were calculated [29] and both RT-qPCR and differential mRNA gene expression calculations for each target gene performed according to [33], using two validated early developmental Arctic charr reference genes, Actb and Ef1a [92]. Reference genes were normalised by randomly selecting one individual within each developmental stage as a calibrator sample. Relative expression quantities (RQ) were calculated according to [33].

Staining of craniofacial elements and digitization

For analyses of morphology, individuals were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained with Alizarin red for bone, and Alcian blue for cartilage, using a modified acid-free double staining protocol [44, 93], see Additional file 1. Based on a previous study [53], as well as preliminary trials, we selected craniofacial elements that were clearly visible at both H and FF stages (Fig. 1; for an overview on all craniofacial structures in developing embryos and time of appearance [53]).

All samples were stained simultaneously within each developmental stage and the same staining solutions were used across both developmental stages to ensure as much consistency as possible. Once stained, individuals were placed in a petri-dish containing 2 and 3% transparent methylcellulose (Appendix S1) for H and FF, respectively, to allow easy maneuverability during photography and to ensure that the embryos lay flat. Individuals were photographed ventrally using a HD digital microscope camera (LEICA MC170 HD) mounted on a stereomicroscope (LEICA M165 C), with a scale set for each photograph. Each individual was photographed twice, each time removing and re-positioning the fish to account for measurement error due to placement. The two sets of photos per individual were duplicated so each individual was represented by a total of four photos: two photos to account for placement error, and two photos to account for digitizing error. Photos of disfigured individuals (N = 8) were removed and remaining photos randomized before digitization. To capture the ventral craniofacial shape of developing Arctic charr and to enable comparisons between H and FF stages, we chose 17 fixed landmarks and 54 sliding semi-landmarks (to increase effect sizes [94]) that were homologous between developmental stages, and placed on ventral surfaces of individuals in tpsDig2 v.2.31 ( [95]; Fig. 1). Landmarks were placed on trophic structures, such as the hyoid arch, Meckel’s cartilage and ethmoid plate. Semi-landmarks were placed at set equal distances along a curve between two fixed landmarks, using tpsDig2. The relative measurement error due to the differences in placement of individuals for photos, as well as digitising error, was evaluated for each developmental stage using Procrustes ANOVA [96] in MorphoJ [97], before taking the average of all photos per individual to remove such measurement errors.

Statistical analyses

Gene expression

Analyses were performed on log2 transformed RQ values and differences in gene expression across stages and families can be found in [29].

Geometric morphometrics for craniofacial shape

All morphometric analyses were conducted in R v.3.3.2 [98] using the R package geomorph v.3.0.3 [99]. Procrustes shape residuals were obtained using a generalized Procrustes analysis [100], which optimally superimposes landmarks according to location, size and orientation. The resulting Procrustes residuals were then used for analysis of object symmetry [96], using the function bilat.symmetry to average landmarks across the line of symmetry to remove variation due to side, as well as averaging our replicates.

All analyses were conducted both with and without the effect of offspring size. For size-free shapes, residuals from the relationship between offspring size and morphology were obtained using procD.lm. The influence of developmental stage (H and FF) and family effects, as well as their interaction, on offspring craniofacial shape was determined using ANOVA from procD.lm (Model 1). As procD.lm uses Type1 sum-of-squares, the position of the last variable was alternated in sequential regressions to obtain an unbiased estimate of the proportion of shape variance attributable to each variable [101]. A PCA was conducted on Procrustes shape residuals to visualize shape changes across families and developmental stage by plotting the first two axes from the PCA, whilst also showing morphological variation at the extremes of those axes in relation to the average morphology using the function plotTangentSpace. The first two PC axes explaining the most variation in craniofacial shape were then correlated with individual offspring size (standard length, mm), family and developmental stage (Model 1b), and significant relationships plotted. Data on egg size was only available as family means (Table 2). Therefore, family and mean egg size were not included within the same model. For Model 2 we tested whether female mean egg size had an effect on offspring craniofacial shape across developmental stages.

Further analyses were then conducted within each developmental stage: Model 3 examined the effect of offspring size on morphology, with family included as a random effect when the inclusion of both family and offspring size were not confounded. In cases where offspring size and family were confounded, they were tested separately; and finally, Model 4 determined the extent that mean female egg size had on craniofacial shape of offspring.

Gene expression and craniofacial shape

To enable comparison of gene expression and craniofacial shape, we used family means within each data set (gene expression and shape at H and FF stages; N = 7) to determine the extent of their covariance. Using family means was necessary as data could not be collected on the same individuals for both gene expression and shape. Two-block partial least squares (PLS [102];) analysis was used to assess whether craniofacial shape (Procrustes residuals) covaried with the relative expression of genes related to skeletogenesis and/or growth within each developmental stage (due to the significant difference in gene expression between H and FF [29]).

A singular value decomposition is obtained from the two covariance matrices (craniofacial shape and relative gene expression), whereby the resulting PLS axes are uncorrelated, and where the first axis explains maximal covariation between both blocks (gene expression and shape [101, 102];). The amount of covariation between the two blocks was measured using a multivariate correlation coefficient (rPLS: [103]), with associated P-values based on 10,000 permutations under the null hypothesis of independence between both blocks of variables.

Individual PC plots for both gene expression and craniofacial shape at each developmental stage were used to facilitate our understanding of how differences in gene expression levels (for both sets of genes) may correspond with differences in craniofacial shape. These PC plots will be displayed with gene loadings from the PLS analyses to determine the strength of genes in any covariance between gene expression and craniofacial shape.

Availability of data and materials

Gene expression data included in this study is available in the Dryad repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.653q97g. The morphological dataset used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- DD:

-

Degree days

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- FF:

-

First feeding

- H:

-

Hatching

- HD:

-

High-definition

- mRNA:

-

Messenger RNA

- mm:

-

Millimetres

- N:

-

Sample size

- PC:

-

Principal component

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- PLS:

-

Two-block partial least squares

- ppm:

-

Parts per million

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- RQ:

-

Relative expression quantities

- RT-qPCR:

-

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SL:

-

Standard length

- μg:

-

Microgram

References

Monaghan P. Early growth conditions, phenotypic development and environmental change. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2008;363:1635–45.

Rubenstein DR, Skolnik H, Berrio A, Champagne FA, Phelps S, Solomon J. Sex-specific fitness effects of unpredictable early life conditions are associated with DNA methylation in the avian glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:1714–28.

Marshall HH, Vitikainen EIK, Mwanguhya F, Businge R, Kyabulima S, Hares MC, et al. Lifetime fitness consequences of early-life ecological hardship in a wild mammal population. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:1712–24.

Forsman A, Ahnesjö J, Caesar S. Fitness benefits of diverse offspring in pygmy grasshoppers. Evol Ecol Res. 2007;9:1305–18.

Lindström J. Early development and fitness in birds and mammals. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:343–8.

Hulsey CD, Fraser GJ, Streelman JT. Evolution and development of complex biomechanical systems: 300 million years of fish jaws. Zebrafish. 2005;2:243–57.

Ornelas-García CP, Córdova-Tapia F, Zambrano L, Bermúdez-González MP, Mercado-Silva N, Mendoza-Garfias B, et al. Trophic specialization and morphological divergence between two sympatric species in Lake Catemaco, Mexico. Ecol Evol. 2018;8:4867–75.

Wainwright PC, Bellwood DR, Westneat MW, Grubich JR, Hoey AS. A functional morphospace for the skull of labrid fishes: patterns of diversity in a complex biomechanical system. Biol J Linn Soc. 2004;82:1–25.

Salzburger W, Mack T, Verheyen E, Meyer A. Out of Tanganyika: genesis, explosive speciation, key-innovations and phylogeography of the haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:17.

Turner GF, Seehausen O, Knight ME, Allender CJ, Robinson RL. How many species of cichlid fishes are there in African lakes? Mol Ecol. 2008;10:793–806.

Young KA, Snoeks J, Seehausen O. Morphological diversity and the roles of contingency, chance and determinism in African cichlid radiations. PLoS One. 2009;4:3.

Cooper WJ, Parsons K, McIntyre A, Kern B, McGee-Moore A, Albertson RC. Bentho-pelagic divergence of cichlid feeding architecture was prodigious and consistent during multiple adaptive radiations within African rift-lakes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9551.

Bolnick DI, Svanbäck R, Fordyce JA, Yang LH, Davis JM, Hulsey CD, et al. The ecology of individuals: incidence and implications of individual specialization. Am Nat. 2003;161:1–28.

Svanbäck R, Eklöv P, Fransson R, Holmgren K. Intraspecific competition drives multiple species resource polymorphism in fish communities. Oikos. 2008;117:114–24.

Swanson BO, Gibb AC, Marks JC, Hendrickson DA. Trophic polymorphism and behavioral differences decrease intraspecific competition in a cichlid, Herichthys minckleyi. Ecology. 2003;84:1441–6.

Martin RA, Pfennig DW. Maternal investment influences expression of resource polymorphism in amphibians: implications for the evolution of novel resource-use phenotypes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9117.

Ruzzante DE, Walde SJ, Cussac VE, Macchi PJ, Alonso MF, Battini M. Resource polymorphism in a Patagonian fish Percichthys trucha (Percichthyidae): phenotypic evidence for interlake pattern variation. Biol J Linn Soc. 2003;78:497–515.

Skúlason S, Smith TB. Resource polymorphisms in vertebrates. Trends Ecol Evol. 1995;10:366–70.

Smith TB, Skúlason S. Evolutionary significance of resource polymorphisms in fishes, amphibians, and birds. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 1996;27:111–33.

Nosil P. Ecological speciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Schluter D. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Snorrason SS, Skúlason S. Adaptive speciation in northern freshwater fishes. In: Dieckmann U, Doebeli M, Metz JAJ, Tautz D, editors. Adaptive speciation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. p. 210–28.

Hoverman JT, Relyea RA. How flexible is phenotypic plasticity? Developmental windows for trait induction and reversal. Ecology. 2007;88:693–705.

Schluter D. Adaptive radiation along genetic lines of least resistance. Evolution. 1996;50:1766–74.

Skúlason S, Parsons KJ, Svanbäck R, Räsänen K, Ferguson MM, Adams CE, et al. A way forward with eco evo devo: an extended theory of resource polymorphism with postglacial fishes as model systems. Biol Rev. 2019;94:1786–808.

Arbeitman MN. Gene expression during the life cycle of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2002;297:2270–5.

Bicskei B, Bron JE, Glover KA, Taggart JB. A comparison of gene transcription profiles of domesticated and wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) at early life stages, reared under controlled conditions. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:884.

Yanai I, Peshkin L, Jorgensen P, Kirschner MW. Mapping gene expression in two Xenopus species: evolutionary constraints and developmental flexibility. Dev Cell. 2011;20:483–96.

Beck SV, Räsänen K, Ahi EP, Kristjánsson BK, Skúlason S, Jónsson ZO, et al. Gene expression in the phenotypically plastic Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus): a focus on growth and ossification at early stages of development. Evol Dev. 2019;21:16–30.

Hoffman EA, Goodisman MA. Gene expression and the evolution of phenotypic diversity in social wasps. BMC Biol. 2007;5:23.

Nolte AW, Renaut S, Bernatchez L. Divergence in gene regulation at young life history stages of whitefish (Coregonus sp.) and the emergence of genomic isolation. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:59.

Sucharov J, Ray K, Brooks EP, Nichols JT. Selective breeding modifies mef2ca mutant incomplete penetrance by tuning the opposing notch pathway. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008507.

Ahi E, Kapralova K, Pálsson A, Maier V, Gudbrandsson J, Snorrason SS, et al. Transcriptional dynamics of a conserved gene expression network associated with craniofacial divergence in Arctic charr. EvoDevo. 2014;5:40.

Ahi EP, Singh P, Lecaudey LA, Gessl W, Sturmbauer C. Maternal mRNA input of growth and stress-response-related genes in cichlids in relation to egg size and trophic specialization. EvoDevo. 2018;9:23.

Kobayashi N, Watanabe M, Kijimoto T, Fujimura K, Nakazawa M, Ikeo K, et al. magp4 gene may contribute to the diversification of cichlid morphs and their speciation. Gene. 2006;373:126–33.

McCubbin AG, Lee C, Hetrick A. Identification of genes showing differential expression between morphs in developing flowers of Primula vulgaris. Sex Plant Reprod. 2006;19:63–72.

Zhang R-J, Chen J, Jiang L-Y, Qiao G-X. The genes expression difference between winged and wingless bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi based on transcriptomic data. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4754.

Segers FHID, Berishvili G, Taborsky B. Egg size-dependent expression of growth hormone receptor accompanies compensatory growth in fish. Proc Royal Soc. 2012;279:592–600.

Badyaev AV, Uller T. Parental effects in ecology and evolution: mechanisms, processes and implications. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2009;364:1169–77.

Kirkpatrick M, Lande R. The evolution of maternal characters. Evolution. 1989;43:485.

Räsänen K, Kruuk LEB. Maternal effects and evolution at ecological time-scales. Funct Ecol. 2007;21:408–21.

Klemetsen A. The charr problem revisited: exceptional phenotypic plasticity promotes ecological speciation in postglacial lakes. Fr Rev. 2010;3:49–74.

Skúlason S, Snorrason SS, Jonsson B. Sympatric morphs, populations and speciation in freshwater fish with emphasis on Arctic charr. In: Magurran AE, May RM, editors. Evolution of biological diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 70–92.

Kapralova KH. Study of morphogenesis and miRNA expression associated with craniofacial diversity in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) morphs. (2014) https://skemman.is/handle/1946/19398. Accessed 16 Sept 2020.

Jónsson B, Skúlason S. Polymorphic segregation in Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus (L.) from Vatnshlídarvatn, a shallow Icelandic lake. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 2000;69:55–74.

Adams CE, Fraser D, Huntingford FA, Greer RB, Askew CM, Walker AF. Trophic polymorphism amongst Arctic charr from loch Rannoch, Scotland. J Fish Biol. 1998;52:1259–71.

Russo T, Costa C, Cataudella S. Correspondence between shape and feeding habit changes throughout ontogeny of gilthead sea bream Sparus aurata L., 1758. J Fish Biology. 2007;71:629–56.

Tuckett QM, Simon KS, Saros JE, Halliwell DB, Kinnison MT. Fish trophic divergence along a lake productivity gradient revealed by historic patterns of invasion and eutrophication. Freshw Biol. 2013;58:2517–31.

Branch GM. Contributions to the functional morphology of fishes. Zool Afr. 1966;2:69–89.

Evans ML, Chapman LJ, Mitrofanov I, Bernatchez L. Variable extent of parallelism in respiratory, circulatory, and neurological traits across lake whitefish species pairs. Ecol Evol. 2013;3:546–57.

Kahilainen KK, Patterson WP, Sonninen E, Harrod C, Kiljunen M. Adaptive radiation along a thermal gradient: Preliminary results of habitat use and respiration rate divergence among whitefish morphs. Ban S, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112085.

Kupren K, Rams I, Żarski D, Kucharczyk D. Early development and allometric growth patterns of rheophilic cyprinid common dace Leuciscus leuciscus (Cyprinidae: Leuciscinae). Ichthyol Res. 2016;63:382–90.

Kapralova KH, Jónsson ZO, Palsson A, Franzdóttir SR, le Deuff S, Kristjánsson BK, et al. Bones in motion: ontogeny of craniofacial development in sympatric Arctic charr morphs. Dev Dyn. 2015;244:1168–78.

Parsons KJ, Cooper WJ, Albertson RC. Modularity of the oral jaws is linked to repeated changes in the craniofacial shape of African cichlids. Int J Evol Biol. 2011;2011:1–10.

Pérez-Miranda F, Mejía O, González-Díaz AA, Martínez-Méndez N, Soto-Galera E, Zúñiga G, et al. The role of head shape and trophic variation in the diversification of the genus Herichthys in sympatry and allopatry. J Fish Biol. 2020;96:1370–8.

Hallgrimsson B, Percival CJ, Green R, Young NM, Mio W, Marcucio R. Morphometrics, 3D imaging, and craniofacial development. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;115:561–97.

Bernatchez L, Renaut S, Whiteley AR, Derome N, Jeukens J, Landry L, et al. On the origin of species: insights from the ecological genomics of lake whitefish. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:1783–800.

Czypionka T, Goedbloed DJ, Steinfartz S, Nolte AW. Plasticity and evolutionary divergence in gene expression associated with alternative habitat use in larvae of the European fire salamander. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2698–713.

Oleksiak MF, Churchill GA, Crawford DL. Variation in gene expression within and among natural populations. Nat Genet. 2002;32:261–6.

Pavey SA, Collin H, Nosil P, Rogers SM. The role of gene expression in ecological speciation: gene expression and speciation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1206:110–29.

Wong PS, Tanaka M, Sunaga Y, Tanaka M, Taniguchi T, Yoshino T, et al. Tracking difference in gene expression in a time-course experiment using gene set enrichment analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107629.

West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:6543–9.

Knutsen GM, Tilseth S. Growth, development, and feeding success of Atlantic cod larvae Gadus morhua related to egg size. Trans Am Fish Soc. 1985;114:507–11.

Michaud WK, Power M, Kinnison MT. Trophically mediated divergence of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus L.) populations in contemporary time. Evol Ecol Res. 2008;10:1051–66.

Adams C, Fraser D, McCarthy I, Shields S, Waldron S, Alexander G. Stable isotope analysis reveals ecological segregation in a bimodal size polymorphism in Arctic charr from loch Tay, Scotland. J Fish Biol. 2003;62:474–81.

Reist JD, Power M, Dempson JB. Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus): a case study of the importance of understanding biodiversity and taxonomic issues in northern fishes. Biodiversity. 2013;14:45–56.

Hendry AP. Ecological speciation! Or the lack thereof? Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2009;66:1383–98.

Nosil P, Harmon LJ, Seehausen O. Ecological explanations for (incomplete) speciation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24:145–56.

Schluter D, McPhail JD. Ecological character displacement and speciation in sticklebacks. Am Nat. 1992;140:85–108.

Primack RB, Miller-Rushing AJ, Corlett RT, Devictor V, Johns DM, Loyola R, et al. Biodiversity gains? The debate on changes in local- vs global-scale species richness. Biol Conserv. 2018;219:A1–3.

Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, et al. World scientists’ warning to humanity: a second notice. BioScience. 2017;67:1026–8.

Parsons KJ, Sheets HD, Skúlason S, Ferguson MM. Phenotypic plasticity, heterochrony and ontogenetic repatterning during juvenile development of divergent Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). J Evol Biol. 2011;24:1640–52.

Tsinganis M. Female life history traits in resource polymorphic Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus, L.). ETH Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich pp, 32. 2016.

Pruess KP. Day-degree methods for pest management. Environ Entomol. 1983;12:613–9.

Pounder KC, Mitchell JL, Thomson JS, Pottinger TG, Sneddon LU. Physiological and behavioural evaluation of common anaesthesia practices in the rainbow trout. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2017;199:94–102.

Priborsky J, Velisek J. A review of three commonly used fish anesthetics. Rev Fish Sci Aquac. 2018;26:417–42.

Leblanc CA-L, Kristjánsson BK, Skúlason S. The importance of egg size and egg energy density for early size patterns and performance of Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus. Aquac Res. 2016;47:1100–11.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82.

Beck SV. The influence of egg size for the diversification of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) morphs. (2019) https://opinvisindi.is/handle/20.500.11815/1017. Accessed 17 Sept 2020.

Ahi EP. Signalling pathways in trophic skeletal development and morphogenesis: insights from studies on teleost fish. Dev Biol. 2016;420:11–31.

Alsop D, Vijayan MM. Development of the corticosteroid stress axis and receptor expression in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R711–9.

Greene MW, Chen TT. Quantitation of IGF-I, IGF-II, and multiple insulin receptor family member messenger RNAs during embryonic development in rainbow trout. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;54:348–61.

Pikulkaew S, Benato F, Celeghin A, Zucal C, Skobo T, Colombo L, et al. The knockdown of maternal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA alters embryo development in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:874–89.

Land SC, Scott CL, Walker D. mTOR signalling, embryogenesis and the control of lung development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;36:68–78.

Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–94.

Lang F, Shumilina E. Regulation of ion channels by the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. FASEB J. 2013;27:3–12.

Jones KT, Greer ER, Pearce D, Ashrafi K. Rictor/TORC2 regulates Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage, body size, and development through sgk-1. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e60.

Pierce AL, Breves JP, Moriyama S, Uchida K, Grau EG. Regulation of growth hormone (GH) receptor (GHR1 and GHR2) mRNA level by GH and metabolic hormones in primary cultured tilapia hepatocytes. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;179:22–9.

Sanders EJ, Harvey S. Growth hormone as an early embryonic growth and differentiation factor. Anat Embryol. 2004;209:1–9.

Guðbrandsson J, Franzdóttir SR, Kristjánsson BK, Ahi EP, Maier VH, Kapralova KH, et al. Differential gene expression during early development in recently evolved and sympatric Arctic charr morphs. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4345.

Di Genova A, Aravena A, Zapata L, Gonzalez M, Maass A, Iturra P. SalmonDB: a bioinformatics resource for Salmo salar and Oncorhynchus mykiss. Database 2011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bar050.

Ahi EP, Guðbrandsson J, Kapralova KH, Franzdóttir SR, Snorrason SS, Maier VH, et al. Validation of reference genes for expression studies during craniofacial development in Arctic charr. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66389.

Walker M, Kimmel C. A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae. Biotech Histochem. 2007;82:23–8.

Collyer ML, Sekora DJ, Adams DC. A method for analysis of phenotypic change for phenotypes described by high-dimensional data. Heredity. 2015;115:357–65.

Rohlf FJ. tpsDig, digitize landmarks and outlines, version 2.05. Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York at Stony Brook. 2005;.

Klingenberg CP, Barluenga M, Meyer A. Shape analysis of symmetric structures: quantifying variation among individuals and asymmetry. Evolution. 2002;56:1909–20.

Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011;11:353–7.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/. 2017.

Adams DC, Otárola-Castillo E. Geomorph: an R package for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol Evol. 2013;4:393–9.

Rohlf FJ, Slice D. Extensions of the Procrustes method for the optimal superimposition of landmarks. Syst Zool. 1990;39:40.

Young NM, Sherathiya K, Gutierrez L, Nguyen E, Bekmezian S, Huang JC, et al. Facial surface morphology predicts variation in internal skeletal shape. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2016;149:501–8.

Rohlf FJ, Corti M. Use of two-block partial least-squares to study covariation in shape. Syst Biol. 2000;49:740–53.

Adams DC, Collyer ML. On the comparison of the strength of morphological integration across morphometric datasets. Evolution. 2016;70:2623–31.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kalina Kapralova for her help and advice during the staining of samples, and also Hólar University Aquaculture Research Station (HUC-ARC) personnel who were involved in the collection, rearing and sampling of offspring. Thank you also to Markos Tsinganis and Anett Reilent for the ageing of females used in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Icelandic Research Fund, Rannis (grant number 141360 to CAL et al., and grant number 173814–051 to SVB), for all aspects of this study, including the design, collection, analyses, interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (SVB, KR, CAL, SS, ZOJ and BKK) were involved in the design and conception of the study. SVB collected and analyzed the data. KR and BKK advised on the analyses, whilst CAL advised on the collection of all samples and ZOJ advised on the collection of gene expression data. All authors (SVB, KR, CAL, SS, ZOJ and BKK) were involved in the writing of the manuscript and the reading and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Fishing in Vatnshlíðarvatn was done with permission obtained from the landowner. Ethics’ committee approval is not needed for regular or scientific fishing in Iceland (the Icelandic law on Animal protection, Law 15/1994, last updated with Law 157/2012). HUC-ARC has an operational license according to Icelandic law on aquaculture (Law 71/2008), which includes clauses of best practices for animal care and experiments: Icelandic laws 55/2013 and regulation 460/2017, licence number FE-1051 for Verið research station.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 2 Table S1.

Procrustes ANOVA of shape differences between replicated craniofacial measurements of Arctic charr embryos. Calculation of measurement error due to digitising error, placement of individuals as well as calculating variation due to fluctuating and directional asymmetry.

Additional file 3 Table S2.

Partial least square (PLS) results from analysis of covariance between craniofacial shape (block 1) at two early life-stages (H, hatching and FF, first feeding) and relative expression of 14 candidate genes related to craniofacial development (block 2) in Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus).

Additional file 4 Figure. S1

. Principal components analysis (PCA) plot showing size-free craniofacial shape variation across families of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn at hatching and first feeding. A total of 71 landmarks were used (see Fig. 1) and resulting deformation grids, with a 2x magnification, are presented at the extremes of both axes to facilitate the interpretation of shape change. Family identity (N offspring 5–9) is represented by different symbols.

Additional file 5 Figure S2

. A graph showing the correlation between technical duplicates of critical threshold (Ct) values (representing 14 genes related to growth and skeletal development) per biological sample of Arctic charr (Salevlinus alpinus) at hatching and first feeding (r = 0.996, P < 0.0001, N = 1776).

Additional file 6 Figure S3.

Principal components analysis (PCA) plots showing both relative gene expression (for growth and skeletal related genes) and ventral size-free craniofacial shapes attributed to family in the brown Arctic charr morph from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn, at a) hatching (H), and b) first feeding (FF). Coloured shapes and associated standard error bars correspond to mean shape of offspring within a family. For gene expression only, green and red arrows show the top three genes (listed from highest to lowest) with the highest PCA loadings driving divergence towards the positive (green) and negative (red) extremes of the PC axes. Deformation grids at the extremes of both axes represent the amount of shape change, with two-fold magnification.

Additional file 7 Figure S4.

Principal components analysis (PCA) plots showing both relative gene expression (for growth and skeletal-related genes) and ventral craniofacial shape variation attributed to family in the brown Arctic charr morph from lake Vatnshlíðarvatn at hatching (H) and first feeding (FF). a) H with offspring size; b) H without offspring size; c) FF with offspring size; and d) FF without offspring size. Coloured shapes and associated standard error bars correspond to mean shape of offspring within a family. For gene expression only, green and red arrows show the top three genes (listed from highest to lowest) with the highest PCA loadings driving divergence towards the positive (green) and negative (red) extremes of the PC axes. Deformation grids at the extremes of both axes represent the amount of shape change, with two-fold magnification.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Beck, S.V., Räsänen, K., Leblanc, C.A. et al. Differences among families in craniofacial shape at early life-stages of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). BMC Dev Biol 20, 21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12861-020-00226-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12861-020-00226-0