Abstract

Background

Berberine (Ber) is a herbal alkaloid with pharmacological activity in general and a high anticancer potency in particular. However, due to its low bioavailability, the difficulty in reaching a target and choosing the right dose, there is a need to improve approaches of Ber use in anticancer therapy. In this study, Ber, noncovalently bound to a carbon nanostructure C60 fullerene (C60) at various molar ratios of the components, was explored against Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC).

Methods

C60–Ber noncovalent nanocomplexes were synthesized in 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 molar ratios. Ber release from the nanocomplexes was studied after prolonged incubation at different pH with the liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of free Ber content. Biological effects of the free and C60-complaxated Ber were studied in vitro towards LLC cells with phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, MTT reduction, caspase activity and wound closure assays. The treatment with C60–Ber nanocomplex was evaluated in vivo with the LLC-tumored C57Bl mice. The mice body weight, tumor size, tumor weight and tumor weight index were assessed for four groups, treated with saline, 15 mg C60/kg, 7.5 mg Ber/kg or 2:1 C60-Ber nanocomplex (15 mg C60/kg, 7.5 mg Ber/kg).

Results

Ber release from C60–Ber nanocomplexes was promoted with medium acidification. LLC cells treatment with C60–Ber nanocomplexes was followed by enhanced Ber intracellular uptake as compared to free Ber. The cytotoxicity of the studied agents followed the order: free Ber < 1:2 < 1:1 < 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex. The potency of cytotoxic effect of 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex was confirmed by 21.3-fold decrease of IC50 value (0.8 ± 0.3 µM) compared to IC50 for free Ber (17 ± 2 µM). C60–Ber nanocomplexes induced caspase 3/7 activation and suppressed the migration activity of LLC cells. The therapeutic potency of 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex was confirmed in a mouse model of LLC. The tumor growth in the group treated with 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex is suppressed by approximately 50% at the end of experiment, while in the tumor-bearing group treated with free Ber no therapeutic effect was detected.

Conclusions

This study indicates that complexation of natural alkaloid Ber with C60 may be a novel therapeutic strategy against lung carcinoma.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Traditional herbal medicine goes back a long way in the Middle East and continues to be a source of new natural therapeutics. Among the herbal secondary metabolites, alkaloids exhibit a broad spectrum of pharmacological properties. Alkaloid-rich plants have been traditionally used throughout the world for the treatment of various disorders including but not limited to inflammation, skin diseases, wounds, fevers, affections of eyes, cancer, digestive and respiratory diseases and microbial infections (Mann 2002; Neag et al. 2018). Many plant extracts, containing alkaloids, have been found to have anticancer effects and have been turned into chemotherapy drugs such as vinblastine, vincristine, paclitaxel and camptothecin (Xia et al. 2014). Accumulating evidence in the recent time suggests beneficial anticancer effects of the isoquinoline quaternary alkaloid berberine (2,3-methylenedioxy-9,10-dimethoxyprotoberberine chloride, Ber). Ber exhibited toxicity towards different cancer models in vitro (Cai et al. 2014; Li et al. 2018; Meeran et al. 2008) and in vivo (Karnam et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2019). The Ber's toxicity was found to be associated with oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. A recent systematic review revealed Ber's high efficiency against lung cancer by inhibition of tumor cells migration ability, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis development (Qi et al. 2014; Tsang et al. 2015).

However, Ber cytotoxicity in cancer cells in comparison to the known drugs that exhibit antitumor activity in nanomolar concentration range is rather weak and a number of setbacks that mainly include Ber's poor water solubility, stability, bioavailability and possible general toxicity challenges its direct transition to a clinic practice (Bao et al. 2015; Fernandes 2020; Mirhadi et al. 2018). Ber is known to induce a significant hormetic dose response, in which low dose stimulated the growth of cancer cells, while the anticancer effect required high doses (Bao et al. 2015; Letasiová et al. 2005) that also challenges an appropriate dosage of the drug. So, new approaches to improve the Ber antitumor efficiency and to attenuate side effects are urgently needed.

An important area of research in modern medicine concerns nanomaterials as promising agents with a wide range of applications. In particular, nanomaterials are currently used as carriers to deliver drugs and other substances to specific cells or tissues (Chaturvedi et al. 2019; Sandoval et al. 2019; Shi et al. 2017). Among them, nanocarbon materials, including C60 fullerene (C60), attract attention as the most biocompatible ones (Goodarzi et al. 2017; Moussa 2018).

C60 is a spherical molecule with a diameter of 0.72 nm and consists of 60 carbon atoms. Its surface contains 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons. The hexagon and pentagon units are connected by a conjugated π-electron system. Given its spherical structure, nanosize and high hydrophobicity, C60 is able to translocate through the lipid plasma membrane, localize in intracellular membranes and interact with active sites of enzymes (Innocenti et al. 2010; Martinez et al. 2016). The π-electron system in the C60 framework is electron deficient, which determines it as an electron-acceptor resulting in an ability to attach easily reagents containing unpaired electrons. As a consequence, C60 acts in the biological systems as a powerful scavenger of free radicals, which results in its anti-inflammatory and organoprotective properties (Eswaran 2018; Ferreira et al. 2018; Gharbi et al. 2005; Halenova et al. 2016; Vereshchaka et al. 2018).

Pristine C60 is a hydrophobic molecule that is shown to embed into biological membranes, to penetrate leukemic cells (Franskevych et al. 2017; Russ et al. 2016) and to localize preferentially in mitochondria (Franskevych et al. 2017; Grebinyk et al. 2018a, 2018b; Russ et al. 2016). In aqueous solution pristine C60 forms stable nanosized clusters (Ritter et al. 2015). Water-soluble pristine C60 at low therapeutic doses was shown to be non-toxic for normal cells in both in vitro and in vivo systems (Prylutska et al. 2019b; Tolkachov et al. 2016). We demonstrated early that the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of C60 against non-cancer human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells was 383.4 µg/mL confirming its low toxicity. No toxic effect of C60 in a dose range of 75–150 mg/kg was observed in vivo on a mice model (LD50 value was 721 mg/kg) (Prylutska et al. 2019b).

The ability of C60 to be covalently or noncovalently functionalized with different bioactive molecules and therapeutics makes this nanostructure a promising drug carrier (Borowik et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2009; Mohajeri et al. 2018). In particular, we demonstrated that noncovalent complexation of doxorubicin and cisplatin with C60 could enhance the anticancer effect of both drugs against leukemic and lung carcinoma cells (Grebinyk et al. 2019b, 2019a; Prylutska et al. 2015, 2017, 2019a).

We have previously described the fast and easy complexation of C60 and Ber in a different molar ratios, evidenced with UV–Vis spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy (AFM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements and could confirm the higher toxic efficiency of the C60–Ber nanocomplex against leukemic CCRF-CEM cells as compared with free Ber (Grebinyk et al. 2019a). Taking into account pharmacological effects of plant alkaloids as therapeutics against different types of cancer, the study of Ber anticancer potential both against a wide spectrum of cancer cells and in experimental animal cancer models is relevant.

The goal of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis of free Ber and C60–Ber nanocomplex antitumor efficiency against Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) in vitro and in vivo.

Results and discussion

Evaluation of the binding constant and the number of binding sites from the fluorescence intensity data

The application of the Ber molecules as therapeutic cargo is strongly dependent on their binding ability to a C60 nanostructure that can affect not only the stability of the C60–Ber nanocomplex, but also its biological effects including targeted accumulation, toxicity and side effects during the anticancer treatment.

Fluorescence spectra were recorded for free Ber aqueous solution and found to be in accordance with the literature data (Díaz et al. 2009; Gumenyuk et al. 2012) as free Ber was characterized by intrinsic yellow fluorescence with a maximum at 545 nm upon excitation at λ = 420 nm (Fig. 1). Regardless of ratio of the components in the C60–Ber nanocomplexes the fluorescence of Ber was quenched by C60 moieties (Fig. 1), suggesting that C60 may well act as an effective proximal quencher. Thus, the fluorescence of Ber in both complexes at 200 µM Ber-equivalent concentration appeared to be quenched by 23, 33 and 49% of free Ber in 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplexes, correspondingly. The observed Ber fluorescence quenching is attributed to the strong electron-accepting capability of C60 (Liu and Troisi 2013), indicating on the close spatial proximity of the components. The obtained data are in agreement with previous investigation of the C60-based nanocomplexes with the common aromatic anticancer drug doxorubicin, whose fluorescence was quenched also up to 50% (Grebinyk 2021; Grebinyk et al. 2019b).

In order to confirm the binding interaction between C60 and Ber, we determined the binding constant and the number of binding sites from the fluorescence intensity measurement of samples. When small molecules (in our case Ber) bind independently to a set of equivalent sites on a macromolecule (in our case C60), the equilibrium between free and bound molecules could be given by the following equation (Suryawanshi et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2009):

where F0 and F are the relative fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of quencher C60, respectively, [C60] is the concentration of quencher, K is the binding constant and n is the number of binding sites per C60 at room temperature and physiological pH 7.4.

The fluorescence intensity data of free and C60-complexated Ber at maxima λex = 420 nm, λem = 420 nm (Fig. 1) were used to build a plot of Y = log(F0 − F)/F versus X = log[C60] whose linear regression was characterized with a straight line, namely: Y = 2.957 + 0.876 × X (R2 = 0.9966). From this, we got that the value of n that was approximately equal to one, indicating that there was one binding site in C60 for Ber during their interaction. The resulting value of K \(\approx\) 103 M−1 [for comparison, the calculated equilibrium constant of C60 binding with doxorubicin molecules was equal to \(\approx\) 60 × 103 M−1 (Mosunov et al. 2017)] indicated a C60–Ber nanocomplex formation and, thus, C60 functionality as a carrier of Ber for the optimization of its biological effects.

Ber release from the C 60–Ber nanocomplex

The kinetics of Ber release was studied after C60–Ber nanocomplexes incubation at different pH in PBS or acetate buffer. The selected pH values were 7.4 and 5.0 to mimic blood pH and cancer cells pH, which is known to be more acidic. It was shown that Ber molecules were released from the nanocomplexes at acidic pH more rapidly than at physiological pH. Thus, at pH 7.4 the cumulative Ber release was 20–34% within 72 h (Fig. 2a), while at pH 5.0 it was more intensive and dependent on the C60 content in the nanocomplex (Fig. 2b). Thus, 70 ± 7% of Ber was released from the 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplexes, whereas only 51 ± 6 and 43 ± 6% from 1:1 and 1:2 C60–Ber nanocomplexes, respectively. Furthermore, the much faster Ber dissociation from C60–Ber nanocomplexes at lower pH was three times higher for 1:1 and 2:1 nanocomplexes at 3 h as compared to neutral pH that is of particular interest for the development of approaches to treat cancer/or malignancies.

Ber intracellular accumulation

The Ber molecule is characterized by strong absorption and fluorescence (Fig. 1) in the visible spectra (Díaz et al. 2009; Gumenyuk et al. 2012), that enables to estimate penetration into and accumulation inside a cell. LLC cells were incubated in the presence of 10 µM Ber or C60–Ber nanocomplexes and examined with both fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry to visualize and quantify the intracellular Ber accumulation correspondingly (Fig. 3a, b).

Fluorescent microscopy images showed that accumulation of 10 µM Ber in LLC cells was insufficient and rather slow (Fig. 3a), while internalization of C60–Ber nanocomplexes appeared to be faster and more efficient (Fig. 3a). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the mean fluorescent intensity of LLC cells, treated for 6 h with C60–Ber nanocomplexes at 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 molar ratios was increased up to 140, 160 and 160%, respectively, as compared with the fluorescence index of cells treated with the free Ber (Fig. 3b). Thus, Ber complexation with C60 nanostructure significantly promoted its uptake and accumulation in LLC cells.

Cell viability

Cell viability is a reliable marker to assess toxicity of Ber towards cancer cell. The direct effect of Ber on viability of most cancer cells is known to be relatively slow and weak and occur at 10–100 µM concentration range after prolonged treatment (Habtemariam 2020; Li et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2009). Moreover, Ber induced a significant hormetic dose response, in which low dose stimulated the growth of cancer cells, while the anticancer effect required high doses (Bao et al. 2015; Letasiová et al. 2005). As the aim of the study was to potentiate the anticancer activity of Ber and to decrease its efficient dose by complexing it with C60, a range of Ber concentrations from 1.3 to 20 µM was used.

The viability of LLC cells incubated in the presence of increasing concentrations of Ber or C60–Ber nanocomplexes in the Ber-equivalent concentrations was estimated with MTT test. No toxic effect of Ber in the 1.3–5 μM concentration range was detected even at 72 h of incubation and a weak hormetic effect was observed at 24 h apparently induced by activation of signaling pathways for adaptive response and cell survival (Fig. 4). A marked inhibitory effect of Ber on LLC cells was revealed only when its concentration was increased to 10 and 20 μM and incubation time was prolonged to 48 and 72 h. Thus, the viability of cells treated with 20 µM Ber was decreased to 76 ± 4, 67 ± 6 and 52 ± 6% from the control at 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 4a–c). In contrast, incubation with C60–Ber nanocomplexes led to the essential suppression of cells viability even at 1.3 μM Ber-equivalent concentration and 24 h incubation (Fig. 4a). The cytotoxic potential of C60–Ber nanocomplexes towards LLC cells was time- and dose-dependent. It was higher as compared with that of free Ber throughout the entire incubation period and followed the order: free Ber < 1:2 < 1:1 < 2:1. Thus, the viability of cells treated for 24, 48 and 72 h with 20 µM 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex was decreased to 46 ± 6, 35 ± 4 and 7 ± 3% from the control, respectively (Fig. 4a–c). No reliable effect of C60 alone at equivalent concentrations was detected (Fig. 4d).

The calculation of the IC50 value enabled the comparative quantitative analysis of LLC sensitivity to free and complexed Ber. Treatment of cells with 1:2 C60–Ber nanocomplex was followed by a slight decrease in the IC50 value for Ber at 72 h of incubation, while at treatment with 1:1and 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplexes a significant drop in IC50 for Ber was revealed at all incubation periods (Table 1).

Treatment with C60–Ber nanocomplex at 2:1 ratio was shown to exhibit the highest effect with a 21.3-fold decrease of the IC50 value for Ber at 72 h of incubation. This is in line with our observations that an early treatment of human T lymphoblastoid cells (CCRF-CEM) with 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex was followed by 6.3 times decrease of IC50 value as compared with that for free Ber (Grebinyk et al. 2019a). These data evidenced the dependence of C60–Ber nanocomplex' toxic effect both on the molar ratio of its components in the complex and on the type of cancer cells.

Caspase 3/7 activity

To determine whether the cytotoxic effect of C60–Ber nanocomplexes was associated with apoptotic death of LLC cells we monitored caspase 3/7 activity (Fig. 5). No reliable effect of 10 µM Ber or free C60 at concentrations used in nanocomplexes on the caspase 3/7 activity was observed.

In cells treated with C60–Ber nanocomplexes the significant caspase 3/7 activation was observed reaching the level of 74 ± 14% above the control at 24 h (Fig. 5). The observed activation of caspase 3/7 cells pointed on the induction of the apoptotic death of LLC cells treated with C60–Ber nanocomplexes.

Cell migration

Lung cancer cells are highly invasive and able to spread rapidly potentially forming metastases. Migration of cancer cells through the tissue stroma into a capillary at the primary tumor site is a necessary stage of the metastatic cascade, with cells that cannot move to a food source do not survive (Huber et al. 2005). With the use of the scratch wound healing assay in a monolayer, we analyzed the ability of C60, Ber and C60–Ber nanocomplex to modify the migration rate of LLC cells. This approach allows the evaluation of a directional cell migratory response and its semi-quantitative estimation. Taking into account the greatest toxic effect of 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex on LLC cells viability (Fig. 4), this nanocomplex in a Ber equivalent 5 and 10 µM concentrations was used here. The results of wound closure image analysis and migration rate measurements are presented in Fig. 6a, b. After migration of the control cells continued for 24 h the width of the wound was decreased. No essential changes in individual cell migration at the edges of the scratch or in a special cell density in the wound area as compared with relative controls were observed when LLC were incubated with C60 or Ber separately.

Treatment with C60–Ber nanocomplex in 10 µM Ber-equivalent concentration resulted in a substantial closure rate decrease and therefore promoted inhibition of cell migration. The scratch zone remained denuded and a value of 53% in relation to migration rate of the control cells and 60% in relation to that of Ber-treated cells was observed after 24 h incubation (Fig. 6b).

Thus, Ber complexation with C60 allowed not only to intensify the influx and intracellular accumulation of alkaloid and to reduce significantly its effective toxic concentration, but also to inhibit the migration potential of lung carcinoma cells.

Antitumor effect in vivo

The assessment of the drug antitumor activity in vivo is a necessary condition for its recommendation for the possible practical application. Taking into account that the acute toxicity of Ber and C60 in mice at i.p. injection indicated the following LD50 values 57.6 mg/kg (Kheir et al. 2010) and 721 mg/kg (Prylutska et al. 2019b), respectively, the selected cumulative doses of Ber and C60 administrated separately or in a nanocomplex in a mice model were 7.5 and 15 mg/kg, respectively.

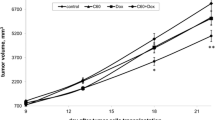

The tumor volume in the control group increased abruptly at 2–4 weeks after cancer cell injection and no statistically significant differences in tumor growth between control group and C60- or Ber-injected groups were recorded (Fig. 7). We then went on to test whether C60 and Ber injection in the form of nanocomplex would provide combination benefit. The tumor growth in the group treated with 2:1 (dose ratio) C60–Ber nanocomplex was delayed and significantly suppressed with tumor volume decrease by approximately 64% and 50% compared to the control group at day 22 and 28, respectively.

Animals of all tested groups had normal fur and activity and no body weight loss was found (Fig. 8) throughout the experiment. Estimation of cancer progression parameters such as tumor mass and tumor weight index confirmed tumor growth inhibition by C60–Ber nanocomplex. Thus, at the end of the experiment 50% diminution in both tumor mass and tumor weight index (Fig. 9) in tumor-bearing animals treated with C60–Ber nanocomplex was observed.

The positive result achieved with the use of C60–Ber nanocomplex on LLC demonstrated its therapeutic benefit in this tumor model.

At micromolar and higher concentration ranges, Ber's efficiency as an anticancer drug is associated with its effects on multiple cellular targets and signaling pathways involved in the control of proliferation, survival and adaptive response of cancer cells, wherein only a moderate in vitro cytotoxicity of the drug was observed in these studies (Kheir et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2019). In this report, we have demonstrated that Ber complexation with C60 allows reducing its effective toxic dose against LLC cells by decreasing the IC50 value in an order. With the use of a mouse model of LLC, we have also demonstrated that treatment of tumor-bearing animals with the C60–Ber nanocomplex was followed by a 50% inhibition of tumor growth in contrast to the treatment with the free Ber in an equivalent dose, which was ineffectual. We suggest that beneficial effect of Ber complexation with C60 could be mediated through C60 ability to prevent or attenuate negative consequences of Ber administration such as drug self-aggregation, oxidation and metabolization (Cui et al. 2015; Kheir et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2019) as well as to promote a targeted drug delivery, to facilitate its accumulation in cancer cells and to affect the tumor microenvironment. Taking into account that the list of cancers that could be targeted by Ber is very large the proposed nanoformulation for enhancing its therapeutic potential by complexation with C60 seems to be prospective.

Conclusions

The data obtained in the study indicate that the strategy of alkaloid noncovalent complexation with C60 nanostructure allows not only to strengthen its toxic effect in low concentration range against LLC cells in vitro, but also to potentiate substantially its anticancer effect in vivo.

C60–Ber nanocomplexes with 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 molar ratio of the components were used in the study. High-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–ESI-MS/MS) analysis revealed that Ber release from created nanocomplexes was more intense in the acidified medium. Treatment of LLC cells with C60–Ber nanocomplexes was followed by both more intense intracellular Ber accumulation confirmed by fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry analysis and a higher cytotoxic effect than at treatment with a free Ber in equivalent concentrations.

A 21.3-fold decrease of the IC50 value for Ber as a component of a 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex as compared to IC50 for free Ber (0.8 ± 0.3 µM and 17 ± 2 µM, respectively) was found for LLC cells. The pronounced caspase 3/7 activation confirmed apoptosis induction in LLC cells treated with C60–Ber nanocomplexes. Similar patterns of Ber's toxic potency enhancement were observed when the C60–Ber nanocomplex was used for treatment of leukemic cells (Grebinyk et al. 2019a) indicating that Ber complexation with C60 could be helpful for optimization of Ber efficiency against cancer cells of different types.

With the use of the scratch wound healing assay in a monolayer we showed that treatment of LLC cells with a 2:1 C60–Ber nanocomplex in 10 μM Ber-equivalent concentration resulted in a substantial closure rate decrease and therefore a promoted inhibition of lung carcinoma cells migration potential.

Taking into account the promising anticancer efficiency of C60–Ber nanocomplex in vitro, we studied its therapeutic potency in a mouse model of LLC. The tumor growth in the group treated with the 2:1 (dose ratio) C60–Ber nanocomplex was shown to be delayed and suppressed with a decrease in tumor volume, mass and weight index by approximately 50% at the end of experiment, while in the group of tumor-bearing animals treated with free Ber no therapeutic effect was detected. This study indicates that C60-based nanocomplexes have a high potential for optimization of alkaloid Ber efficiency against lung carcinoma.

Methods

Chemicals

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, l-glutamine, and trypsin were obtained from Biochrom (Berlin, Germany). Formic acid, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-sodium acetate anhydrous, 2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) and Ber were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St-Louis, MO, USA). Acetic acid, sodium chloride, methanol (HPLC–MS grade), water (HPLC–MS grade), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and trypan blue were used from Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Preparation of C 60–Ber nanocomplex

The pristine C60 fullerene aqueous solution (C60FAS; purity > 99.5%, concentration 2.6 mg/mL) was prepared according to the proposed method (Scharff et al. 2004; Tolkachov et al. 2016). Briefly, it based on the transferring C60 from toluene to an aqueous phase with the help of ultrasonic treatment. Pristine C60 form aggregates in aqueous solution producing stable colloid solution (within 12–18 months at storage temperature of + 4 0C) which contains both individual C60 and its nanoclusters (Prilutski et al. 1998, 1999). A variety of physical methods has been applied in order to understand the specificity of C60 cluster formation. Characterization of C60 particles in aqueous solution has been accomplished by means of UV–Vis, FTIR and Raman spectroscopy, scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), AFM, DLS as well as small angle neutron scattering (SANS) techniques (Borowik et al. 2018; Peudus et al. 2020; Prylutska et al. 2017; Prylutska et al. 2019b; Prylutskyy et al. 2014; Ritter et al. 2015). The mechanism of C60 molecule dispersal in aqueous solution might be explained by a formation of a covalent bond between the hydroxyls and carbons in the C60 cage, as a result of ultrasound treatment that culminates in a consequent easy C60 dissolution (Prylutskyy et al. 2014).

The isoquinoline quaternary alkaloid Ber (2,3-methylenedioxy-9,10-dimethoxyprotoberberine chloride, CAS No. 2086-83-1, molecular weight of 353.36 g/mol) was dissolved in distilled water at an initial concentration of 1 mg/mL.

The preparation of C60–Ber nanocomplexes was executed according to the protocol (Grebinyk et al. 2019a): C60FAS and Ber were mixed in various molar ratios, namely: C60–Ber as 1:1 (208:208 µM), 1:2 (208:416 µM) and 2:1 (208:104 µM). The resulting C60 + Ber aqueous solutions were treated in the ultrasonic disperser for 20 min, and after that stirred magnetically for 18 h at room temperature.

Note that the formation of C60–Ber nanocomplexes in aqueous solution was confirmed by the UV–Vis spectroscopy, AFM and DLS measurements (Grebinyk et al. 2019a).

Fluorescence intensity analysis

The fluorescence spectra of the free Ber and C60–Ber complex were measured at the following parameters: λex = 420 nm, wavelength range 450–750 nm, wavelength step size: 2 nm, number of flashes per well: 25. A volume of 100 μL of the studied solutions was measured in the 96-well plates Sarstedt (Nümbrecht, Germany) with a multimode microplate spectrometer Tecan Infinite M200 Pro (Männedorf, Switzerland).

Drug release

To test the drug release from the C60–Ber nanocomplexes the HPLC–ESI-MS/MS analysis was used as described in Grebinyk et al. (2019a). C60–Ber samples (500 µL) in a 10 µM Ber-equivalent concentration were incubated for 72 h under the identical conditions adopted from cell-based experiments. Acetate and PBS buffers were used for pH 5.0 and 7.4, respectively. To study the Ber release dynamics each sample was taken at the certain time and filtered with the centrifugal filters Amicon Ultra-0.5 3 K (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St-Louis, MO, USA), supplied with the Ultracel® low-binding regenerated cellulose membrane 3 K (3000 MWCO) and two microcentrifuge tubes. According to manufacturer’s instructions, the samples, placed in the Amicon Ultra-0.5 device, were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min for filtration in one tube to collect filtrate. On the next step, the Amicon Ultra-0.5 device was placed reverse spin upside down in a new centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1000 g for 2 min for recovery. The content of free Ber in the first tube after filtration was assessed with HPLC–ESI-MS/MS.

The liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry was employed with Nexera HPLC system coupled to the LCMS-8040 Tandem Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer and equipped with an Electro Spray Ionization source (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Elution and separation of Ber was performed using the Eclipse XDB-C18 column under gradient conditions with a mobile phase of methanol and a 0.1% formic acid water solution. The obtained data were normalized with the respective buffer value and expressed as a percentage of the control value, analyzed at 0 h.

Cell culture

LLC cells were kindly supplied by the Bank of Cell Cultures and Transplantable Experimental Tumors of R.E. Kavetsky Institute of Experimental Pathology, Oncology and Radiobiology, NAS of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine). Cells were maintained in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were cultured in 25 cm2 culture flasks at a 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator binder (Tuttlingen, Germany). The passaging was performed once cells reached ≈80%. Treatment with trypsin (1:10 in PBS) was used to detach adherent cells. The number of viable cells was counted upon 0.1% trypan blue staining with a Roche Cedex XS analyzer (Basel, Switzerland).

Ber intracellular accumulation

LLC cells (2 × 105) were incubated in 6-well plates for 3 and 6 h in the presence of 10 µM Ber or C60 Ber nanocomplexes. After incubation, cells were analyzed with the flow cytometer BD FACSJazz™ (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at λex = 488 nm and λem = 530/40 nm and the Keyence BZ-9000 BIOREVO fluorescence microscope (Osaka, Japan), equipped with a green filter (λex = 435 nm, λem > 515 nm). The Keyence BZ-II Viewer acquisition software (Osaka, Japan) was used.

Cell viability

LLC cells (1.6 × 104 cells/well), cultured in 96-well cell culture plates Sarstedt (Nümbrecht, Germany) for 24 h, were treated with the 1% FBS DMEM medium containing 0–80 µM Ber or C60–Ber nanocomplexes in a Ber-equivalent concentration. Cell viability was determined with an MTT reduction assay (Carmichael et al. 1987) at 24, 48 and 72 h. Briefly, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in the presence of 0.5 mg/mL MTT. Diformazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO and determined at 570 nm with a microplate reader Tecan Infinite M200 Pro (Männedorf, Switzerland).

Caspase 3/7 activity

LLC cells (1.6 × 104 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. Cells were treated with C60 and Ber separately or C60–Ber nanocomplexes in 10 µM Ber-equivalent concentration for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Caspase 3/7 activity was determined by the Promega Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Activity assay kit (Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The plates were removed from the incubator and equilibrated to room temperature for 30 min. An equal volume of Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent containing a luminogenic peptide substrate was added followed by gentle mixing with a plate shaker at 300 rpm for 1 min. The plates were then incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The luminescence intensity of the products of caspase 3/7 reaction was measured with the Tecan Infinite M200 Pro microplate reader (Männedorf, Switzerland).

Cell migration assay

To study cell migration we used the in vitro wound closure assay, which imitated cell migration during wound healing in vivo (Rodriguez et al. 2005). LLC cells were seeded into a 6-wells plate (106 cells/well) and cultured overnight at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 up to 90% confluence. Then a wound with a width of ~ 0.2 mm was scratched with a sterile 200-µL pipette tip in the middle of the monolayer. Cells were then incubated with the new complete DMEM containing 1 µM mitomycin C to eliminate effects of cellular proliferation and treated with C60, Ber or C60–Ber nanocomplexes.

The wound closure was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy. Photoimages were taken at 0 and 24 h after cells treatment. Wound widths were estimated using ImageJ software version 1.47 h (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij), migration rate was calculated using formula (Rodriguez et al. 2005):

where W0 and W24 are widths of cell-free gap at indicated time points (0 and 24 h).

In vivo study

LLC cells (5 × 105) in 100 μL saline were injected subcutaneously into the axilla of the right forelimb of the C57Bl male mice aged 6 weeks. The mice were held under standard laboratory conditions and had free access to laboratory rodent chow and water.

On the second day after tumor inoculation the mice were randomized into four treatment groups of six mice each and 200 µL of the following agents were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) 5 times every other day: 1—0.9% saline (control, untreated); 2—C60FAS in a total dose 15 mg C60/kg; 3—Ber in a total dose 7.5 mg/kg; 4—C60–Ber nanocomplex in a total dose 22.5 mg/kg (15 mg C60/kg and 7.5 mg Ber/kg).

From the 8th day of the experiment the size of the tumor was measured every 3–4 days. Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated by the formula (d2 × D)/2, where d and D are the shortest and longest diameter in mm. At day 29 of the experiment mice were killed by standard procedure of cervical dislocation. Tumor weight was estimated as a difference in the weight of the limb with tumor and without one. Tumor weight index (%) was calculated as mass of tumor (g)/weight of animal (g) × 100% (Faustino-Rocha et al. 2013).

Statistics

All experiments were carried out with a minimum of four replicates. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Origin 9.0 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) by one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher LSD post hoc test. Differences between groups were considered to be significant at p < 0.05. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated with specialized software GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Individual concentration–effect curves were generated by fitting the logarithm of the compound concentration versus the corresponding normalized cell viability using nonlinear regression.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bao J, Huang B, Zou L, Chen S, Zhang C, Zhang Y et al (2015) Hormetic effect of berberine attenuates the anticancer activity of chemotherapeutic agents. PLoS ONE 10(9):e0139298

Borowik A, Prylutskyy Y, Kawelski Ł, Kyzyma O, Bulavin L, Ivankov O et al (2018) Does C60 fullerene act as a transporter of small aromatic molecules? Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 164:134–143

Cai Y, Xia Q, Luo R, Huang P, Sun Y, Shi Y et al (2014) Berberine inhibits the growth of human colorectal adenocarcinoma in vitro and in vivo. J Nat Med 68(1):53–62

Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB (1987) Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res 47(4):936–942

Chaturvedi VK, Singh A, Singh VK, Singh MP (2019) Cancer nanotechnology: a new revolution for cancer diagnosis and therapy. CDM 20(6):416–429

Cui H-M, Zhang Q-Y, Wang J-L, Chen J-L, Zhang Y-L, Tong X-L (2015) Poor permeability and absorption affect the activity of four alkaloids from Coptis. Mol Med Rep 12(5):7160–7168

Díaz MS, Freile ML, Gutiérrez MI (2009) Solvent effect on the UV/Vis absorption and fluorescence spectroscopic properties of berberine. Photochem Photobiol Sci 8(7):970–974

Eswaran SV (2018) Water soluble nanocarbon materials: a panacea for all? Curr Sci 114(9):5

Faustino-Rocha A, Oliveira PA, Pinho-Oliveira J, Teixeira-Guedes C, Soares-Maia R, da Costa RG et al (2013) Estimation of rat mammary tumor volume using caliper and ultrasonography measurements. Lab Anim (NY) 42(6):217–224

Fernandes JA (2020) Improving the solubility of berberine. Acta Crystallogr C Struct Chem 76(Pt 2):117

Ferreira CA, Ni D, Rosenkrans ZT, Cai W (2018) Scavenging of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with nanomaterials. Nano Res 11(10):4955–4984

Franskevych D, Palyvoda K, Petukhov D, Prylutska S, Grynyuk I, Schuetze C et al (2017) Fullerene C60 penetration into leukemic cells and its photoinduced cytotoxic effects. Nanoscale Res Lett 12(1):40

Gharbi N, Pressac M, Hadchouel M, Szwarc H, Wilson SR, Moussa F (2005) [60]Fullerene is a powerful antioxidant in vivo with no acute or subacute toxicity. Nano Lett 5(12):2578–2585

Goodarzi S, Da Ros T, Conde J, Sefat F, Mozafari M (2017) Fullerene: biomedical engineers get to revisit an old friend. Mater Today 20(8):460–480

Grebinyk A, Grebinyk S, Prylutska S, Ritter U, Matyshevska O, Dandekar T et al (2018a) C60 fullerene accumulation in human leukemic cells and perspectives of LED-mediated photodynamic therapy. Free Radic Biol Med 124:319–327

Grebinyk A, Grebinyk S, Prylutska S, Ritter U, Matyshevska O, Dandekar T et al (2018b) HPLC-ESI-MS method for C60 fullerene mitochondrial content quantification. Data Brief 19:2047–2052

Grebinyk A, Prylutska S, Buchelnikov A, Tverdokhleb N, Grebinyk S, Evstigneev M et al (2019a) C60 fullerene as an effective nanoplatform of alkaloid Berberine delivery into leukemic cells. Pharmaceutics 11(11):586

Grebinyk A, Prylutska S, Grebinyk S, Prylutskyy Y, Ritter U, Matyshevska O et al (2019b) Complexation with C60 fullerene increases doxorubicin efficiency against leukemic cells in vitro. Nanoscale Res Lett 14(1):61

Grebinyk A (2021) Synergistic Chemo- and Photodynamic Treatment of Cancer Cells with C60 Fullerene Nanocomplexes. Universität Würzburg. https://doi.org/10.25972/OPUS-22207

Gumenyuk VG, Bashmakova NV, Kutovyy SY, Yashchuk VM, Zaika LA (2012) Binding parameters of alkaloids berberine and sanguinarine with DNA. Ukr J Phys 56(6): 524–533.

Habtemariam S (2020) Recent advances in berberine inspired anticancer approaches: from drug combination to novel formulation technology and derivatization. Molecules 25(6):1426

Halenova TI, Vareniuk IM, Roslova NM, Dzerzhynsky ME, Savchuk OM, Ostapchenko LI et al (2016) Hepatoprotective effect of orally applied water-soluble pristine C60 fullerene against CCl4-induced acute liver injury in rats. RSC Adv 6(102):100046–100055

Huber MA, Kraut N, Beug H (2005) Molecular requirements for epithelial-mesenchymal transition during tumor progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol 17(5):548–558

Innocenti A, Durdagi S, Doostdar N, Strom TA, Barron AR, Supuran CT (2010) Nanoscale enzyme inhibitors: fullerenes inhibit carbonic anhydrase by occluding the active site entrance. Bioorg Med Chem 18(8):2822–2828

Karnam KC, Ellutla M, Bodduluru LN, Kasala ER, Uppulapu SK, Kalyankumarraju M et al (2017) Preventive effect of berberine against DMBA-induced breast cancer in female Sprague Dawley rats. Biomed Pharmacother 92:207–214

Kheir MM, Wang Y, Hua L, Hu J, Li L, Lei F et al (2010) Acute toxicity of berberine and its correlation with the blood concentration in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 48(4):1105–1110

Letasiová S, Jantová S, Múcková M, Theiszová M (2005) Antiproliferative activity of berberine in vitro and in vivo. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 149(2):461–463

Li J, Liu F, Jiang S, Liu J, Chen X, Zhang S et al (2018) Berberine hydrochloride inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer via the suppression of the MMP2 and Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathways. Oncol Lett 15(5):7409–7414

Liu T, Troisi A (2013) What makes fullerene acceptors special as electron acceptors in organic solar cells and how to replace them. Adv Mater Weinheim 25(7):1038–1041

Lu F, Haque SKA, Yang S-T, Luo PG, Gu L, Kitaygorodskiy A et al (2009) Aqueous compatible fullerene-doxorubicin conjugates. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces 113(41):17768

Mann J (2002) Natural products in cancer chemotherapy: past, present and future. Nat Rev Cancer 2(2):143–148

Martinez ZS, Castro E, Seong C-S, Cerón MR, Echegoyen L, Llano M (2016) Fullerene derivatives strongly inhibit HIV-1 replication by affecting virus maturation without impairing protease activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60(10):5731–5741

Meeran SM, Katiyar S, Katiyar SK (2008) Berberine-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells is initiated by reactive oxygen species generation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 229(1):33–43

Mirhadi E, Rezaee M, Malaekeh-Nikouei B (2018) Nano strategies for berberine delivery, a natural alkaloid of Berberis. Biomed Pharmacother 104:465–473

Mohajeri M, Behnam B, Sahebkar A (2018) Biomedical applications of carbon nanomaterials: Drug and gene delivery potentials. J Cell Physiol 298–319.

Mosunov AA, Pashkova IS, Sidorova M, Pronozin A, Lantushenko AO, Prylutskyy YI et al (2017) Determination of the equilibrium constant of C60 fullerene binding with drug molecules. Phys Chem Chem Phys 19(9):6777–6784

Moussa F (2018) 5—[60]Fullerene and derivatives for biomedical applications. In: Narayan R (ed) Nanobiomaterials. Woodhead Publishing, pp 113–136

Neag MA, Mocan A, Echeverría J, Pop RM, Bocsan CI, Crişan G et al (2018) Berberine: botanical occurrence, traditional uses, extraction methods, and relevance in cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic, and renal disorders. Front Pharmacol 2018(9):557

Peudus DA, Mosunov AA, Mykhina YV, Prylutskyy YI, Evstigneev MP (2020) Fractal C60 fullerene aggregation: equilibrium thermodynamics approach. Chem Phys Lett 742:137161

Prilutski YI, Durov SS, Yashchuk VN, Ogul’chansky TY, Pogorelov VE, Astashkin YA et al (1999) Theoretical predictions and experimental studies of self-organized C60 nanoparticles in water solution and on the support. In: Châtelain A, Bonard J-M (eds) The European physical journal D. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 341–343

Prilutski Y, Durov S, Bulavin L, Pogorelov V, Astashkin Y, Yashchuk V et al (1998) Study of structure of colloidal particles of fullerenes in water solution. Molecular crystals and liquid crystals science and technology. Section A. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst 324(1):65–70

Prylutska SV, Skivka LM, Didenko GV, Prylutskyy YI, Evstigneev MP, Potebnya GP et al (2015) Complex of C60 fullerene with doxorubicin as a promising agent in antitumor therapy. Nanoscale Res Lett 10(1):499

Prylutska S, Politenkova S, Afanasieva K, Korolovych V, Bogutska K, Sivolob A et al (2017) A nanocomplex of C60 fullerene with cisplatin: design, characterization and toxicity. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 8:1494–1501

Prylutska S, Grynyuk I, Skaterna T, Horak I, Grebinyk A, Drobot L et al (2019a) Toxicity of C60 fullerene-cisplatin nanocomplex against Lewis lung carcinoma cells. Arch Toxicol 93(5):1213–1226

Prylutska SV, Grebinyk AG, Lynchak OV, Byelinska IV, Cherepanov VV, Tauscher E et al (2019b) In vitro and in vivo toxicity of pristine C60 fullerene aqueous colloid solution. Fullerenes Nanotubes Carbon Nanostruct 27(9):715–728

Prylutskyy YI, Petrenko VI, Ivankov OI, Kyzyma OA, Bulavin LA, Litsis OO et al (2014) On the origin of C60 fullerene solubility in aqueous solution. Langmuir 30(14):3967–3970

Qi H, Xin L, Xu X, Ji X, Fan L (2014) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers to predict response of Berberine in suppressing lung cancer invasion and metastasis. J Transl Med 12:22

Ritter U, Prylutskyy YI, Evstigneev MP, Davidenko NA, Cherepanov VV, Senenko AI et al (2015) Structural features of highly stable reproducible C60 fullerene aqueous colloid solution probed by various techniques. Fullerenes Nanotubes Carbon Nanostruct 23(6):530–534

Rodriguez LG, Wu X, Guan J-L (2005) Wound-healing assay. Methods Mol Biol 294:23–29

Russ KA, Elvati P, Parsonage TL, Dews A, Jarvis JA, Ray M et al (2016) C60 fullerene localization and membrane interactions in RAW 264.7 immortalized mouse macrophages. Nanoscale 8(7):4134–4144

Sandoval J, Ventura-Sobrevilla J, Boone-Villa D, Ramos-González R, Velázquez M, Silva-Belmares Y et al (2019) Chapter 14—Carbon nanomaterials as pharmaceutic forms for sustained and controlled delivery systems. In: Grumezescu AM (ed) Nanomaterials for drug delivery and therapy. William Andrew Publishing, pp 403–434

Scharff P, Carta-Abelmann L, Siegmund C, Matyshevska OP, Prylutska SV, Koval TV et al (2004) Effect of X-ray and UV irradiation of the C60 fullerene aqueous solution on biological samples. Carbon 42(5):1199–1201

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC (2017) Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 17(1):20–37

Sun Y, Xun K, Wang Y, Chen X (2009) A systematic review of the anticancer properties of berberine, a natural product from Chinese herbs. Anticancer Drugs 20(9):757–769

Suryawanshi VD, Walekar LS, Gore AH, Anbhule PV, Kolekar GB (2016) Spectroscopic analysis on the binding interaction of biologically active pyrimidine derivative with bovine serum albumin. J Pharm Anal 6(1):56–63

Tolkachov M, Sokolova V, Loza K, Korolovych V, Prylutskyy Y, Epple M et al (2016) Study of biocompatibility effect of nanocarbon particles on various cell types in vitro. Materialwiss Werkstofftech 47(2–3):216–221

Tsang CM, Cheung KCP, Cheung YC, Man K, Lui VW-Y, Tsao SW, et al.( 2015) Berberine suppresses Id-1 expression and inhibits the growth and development of lung metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Mol Basis of Dis 1852(3):541–51.

Vereshchaka IV, Bulgakova NV, Maznychenko AV, Gonchar OO, Prylutskyy YI, Ritter U et al (2018) C60 fullerenes diminish muscle fatigue in rats comparable to N-acetylcysteine or β-alanine. Front Physiol 9:517

Xia J, Chen J, Zhang Z, Song P, Tang W, Kokudo N (2014) A map describing the association between effective components of traditional Chinese medicine and signaling pathways in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Drug Discov Ther 8(4):139–153

Xu J, Long Y, Ni L, Yuan X, Yu N, Wu R et al (2019) Anticancer effect of berberine based on experimental animal models of various cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 19:1–20

Zhang Y, Yu Y, Yan X, Wang W, Tian X, Wang L et al (2019) Different structures of berberine and five other protoberberine alkaloids that affect P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux capacity. Acta Pharmacol Sin 40(1):133–142

Zhao L, Liu R, Zhao X, Yang B, Gao C, Hao X et al (2009) New strategy for the evaluation of CdTe quantum dot toxicity targeted to bovine serum albumin. Sci Total Environ 407(18):5019–5023

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL (with the Technical University of Applied Sciences Wildau). We thank the Brandenburg programme “Strengthening technological and application-oriented research at scientific institutions (StaF Directive)” (FullDrug, No. 85037298). This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Ukraine No. 2020.02/0060, and in part by a grant from the Ukrainian–Chinese Intergovernmental Science No. M/88-2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, funding acquisition; SP: methodology, formal analysis, software, validation, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, funding acquisition; SG: methodology, software, validation, investigation; ME: validation, investigation; IK: Validation, Investigation; TS: Validation, Investigation; IH: validation, investigation; YS: validation, investigation; LD: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; OM: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; YP: conceptualization, writing—review ans editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; UR: resources, methodology, funding acquisition; MF: resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were carried out following the recommendations of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Research and Scientific Purposes (Strasbourg, 1986), and the Procedure for conducting animal research, experiments by scientific institutions (Order № 249 of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine from 01.03.2012), and were approved by the ethical committee of the Palladin Institute of Biochemistry of NAS of Ukraine.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Grebinyk, A., Prylutska, S., Grebinyk, S. et al. Antitumor efficiency of the natural alkaloid berberine complexed with C60 fullerene in Lewis lung carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Nano 12, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-021-00096-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12645-021-00096-6