Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly worldwide since its discovery in December 2019. Research published since the COVID-19 outbreak has focused on whether semen quality and reproductive hormone levels are affected by COVID-19. However, there is limited evidence on semen quality of uninfected men. This study aimed to compare semen parameters among uninfected Chinese sperm donors before and after the COVID-19 pandemic to determine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic-related stress and lifestyle changes on uninfected men.

Results

All semen parameters were non-significant except semen volume. The average age of sperm donors was higher after the COVID-19 (all P < 0.05). The average age of qualified sperm donors increased from 25.9 (SD: 5.3) to 27.6 (SD: 6.0) years. Before the COVID-19, 45.0% qualified sperm donors were students, but after the COVID-19, 52.9% were physical laborers (P < 0.05). The proportion of qualified sperm donors with a college education dropped from 80.8 to 64.4% after the COVID-19 (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Although the sociodemographic characteristics of sperm donors changed after the COVID-19 pandemic, no decline in semen quality was found. There is no concern about the quality of cryopreserved semen in human sperm banks after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Résumé

Contexte

La maladie due au Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) s’est propagée rapidement dans le monde entier depuis sa découverte en décembre 2019. Les recherches publiées depuis l’éclosion de la COVID-19 se sont concentrées sur la question de savoir si la qualité du sperme et les niveaux d’hormones reproductives étaient affectés par la COVID-19. Il existe, cependant, peu de preuves sur la qualité du sperme des hommes non infectés. Cette étude visait à comparer, avant et après la pandémie de COVID-19, les paramètres du sperme chez les donneurs de sperme Chinois non infectés, afin de déterminer l’impact du stress lié à la pandémie de COVID-19 et aux changements de mode de vie sur les hommes non infectés.

Résultats

Toutes les valeurs des paramètres du sperme étaient non significatives, à l’exception du volume de sperme. L’âge moyen des donneurs de sperme était plus élevé après la COVID-19 (tous p < 0,05). L’âge moyen des donneurs de sperme admissibles est passé de 25,9 ans (ET : 5,3) à 27,6 ans (ET : 6,0). Avant la COVID-19, 45 % des donneurs de sperme admissibles étaient des étudiants, mais après la COVID-19, 53 % étaient des travailleurs physiques (p < 0,05). La proportion de donneurs de sperme admissibles ayant fait des études secondaires est passée de 80,8 % à 64,4 % après la COVID-19 (p < 0,05).

Conclusion

Bien que les caractéristiques sociodémographiques des donneurs de sperme aient changé après la pandémie de COVID-19, aucune baisse de la qualité du sperme n’a été constatée. Il n’y a aucune préoccupation quant à la qualité du sperme cryoconservé dans les banques de sperme humain après la pandémie de COVID-19.

Mots-clés

COVID-19, Qualité du Sperme, Donneur de Sperme, Banque de Sperme humain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its discovery in December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has rapidly spread worldwide, posing a major threat to the health of people. Health behaviors, stress levels, and financial security of the general population have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic [1,2,3]. SARS-CoV-2 binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in humans [4, 5], which is enriched in spermatogonia and Leydig and Sertoli cells [6]. These findings raise concerns regarding the effects of COVID-19 on male semen quality. Holtmann et al. [7] demonstrated a decline in the number of progressively motile spermatozoa, sperm concentration, and total sperm count in men with moderate infection. Gacci et al. [8] found that 11 out of 43 recovered patients demonstrated oligo-crypto-azoospermia. However, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the effects of COVID-19 on male fertility.

As the most widespread pandemic in this century, the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns about the reproductive health of uninfected men. After the COVID-19 outbreak, people experienced more emotional stress reactions, including anxiety and depression [9, 10]; more sitting time and screen time; and less physical activity [11]. The influence of psychological stress, lifestyle, and mobile phone use on semen quality has long been discussed [12,13,14]. However, there is limited evidence on semen quality of uninfected men during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic-related stress and lifestyle changes on semen quality of uninfected men based on 1487 semen samples collected from the Shandong Human Sperm Bank of China.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study of sperm donors was performed at the Shandong Human Sperm Bank of China from January to June 2019 and January to June 2020. The sociodemographic characteristics including age and abstinence time of all sperm donors; and body mass index (BMI), education level, and occupation of qualified sperm donors, were obtained from the database of the Shandong Human Sperm Bank. Sperm donors were strictly screened according to the standard guidelines issued in 2003 by China’s Ministry of Health. Individuals meeting the criteria for donors were qualified sperm donors (Fig. 1). After the outbreak of the COVID-19, the sperm donors were asked to complete the questionnaire for COVID-19 and show their travel codes, which can indicate the history of close physical contact or travel to high-risk areas, and the nasopharyngeal swab testing results, when they visited the sperm bank to ensure that they were not infected with SARS-CoV-2. All sperm donors signed informed consent allowing the use of their semen samples and clinical data in scientific research. The study was approved by the Reproductive Medicine Ethics Committee, Hospital for Reproductive Medicine Affiliated to Shandong University.

Semen collection and analysis

The 1217 semen samples of candidate sperm donors and 270 samples of qualified sperm donors were included in the study. All semen samples were obtained by masturbation into a sterile plastic container after 2–7 days of abstinence. Semen analysis was performed according to the guidelines of the World Health Organization Fifth edition [15]. The semen samples were liquefied in a 37 °C water bath and analyzed within 1 h after collection. The semen parameters, including volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, progressive motility, total motility, number of progressive motility, and normal sperm morphology were assessed. Semen volume was estimated by graduated pipettes. Sperm concentration and motility were assessed by the manual counting method with the Makler chamber. Total sperm count was calculated as sperm concentration multiplied by semen volume. During the research, quality control was conducted regularly in the laboratory with satisfactory results of CV within 10%.

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data distribution was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to describe differences in sociodemographic characteristics and semen parameters before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were given as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) for the results. Differences between categorical data were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Natural-log transformations were performed on semen parameters to approximate the normality assumption. To eliminate the effects of covariates on qualified sperm donors, including age, education level, and occupation, we adjusted for covariates by multiple linear regression analysis. We used SPSS 24.0 to perform the statistical analysis. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

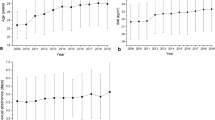

The sociodemographic characteristics and semen parameters of candidate sperm donors are shown in Table 1. The average age of candidate sperm donors was 26.0 (SD: 5.2) years before the outbreak, while it was 26.7 (SD: 5.7) years after the outbreak (P < 0.05). After the outbreak, the median semen volume was 2.4 (IQR: 1.9) ml, compared with 2.0 (IQR: 1.6) ml before the outbreak (P < 0.05). There were no findings of significant differences in other semen parameters of candidate sperm donors before and after the COVID-19 (all P > 0.05).

The sociodemographic characteristics and semen parameters of qualified sperm donors are shown in Table 2. The average age of qualified sperm donors was 25.9 (SD: 5.3) years before the outbreak and 27.6 (SD: 6.0) years after the outbreak (P < 0.05). Significant differences in the distribution of education level and occupation were observed (all P < 0.05). The education level of qualified sperm donors was college or higher, accounting for 80.8% and 64.4% before and after the outbreak, respectively. Before the outbreak, 45.0% qualified donors were students and 22.5% were physical laborers. After the outbreak, 19.2% qualified donors were students and 52.9% were physical laborers. We did not find significant differences in volume, sperm concentration, total sperm count, progressive motility, total motility, number of progressive motility, and normal sperm morphology of qualified sperm donors before and after the COVID-19 (all P > 0.05).

We used linear regression analysis to eliminate the effects of covariates on semen quality of qualified sperm donors (Table 3). Model 1 adjusted for age. Model 2 adjusted for age and education level and model 3 adjusted for age, education level, and occupation. After adjusting for the above covariates, there were still no statistical differences in all semen parameters before and after the COVID-19 (all P > 0.05).

Discussion

Our results showed no significant differences in semen parameters, except semen volume of candidate sperm donors, which increased after the outbreak. Interestingly, the average age of candidate and qualified sperm donors was higher after the outbreak, and education level and occupation of qualified sperm donors changed significantly after the outbreak. Most qualified sperm donors were students before the COVID-19 pandemic. After the outbreak, most university students did not return to school and stayed home, as the Chinese government took effective prevention and control measures to reduce coronavirus transmission [16]. Furthermore, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many factories suspended production; therefore, many physical laborers had the time and energy to donate semen. This clearly changed the occupation, education level, and average age of sperm donors. More healthy young men, such as physical laborers, should be encouraged to be sperm donors to meet the increasing demand for donor sperm in the field of reproductive medicine.

In our study, the average age of qualified sperm donors was higher after the COVID-19. However, the effects of male aging on fertility remains uncertain and the review of the literature shows inconsistent results [17]. Previous studies showed that male aging was associated with a decline in fertility, as reflected by decreased pregnancy rates and increased time to pregnancy and frequency of subfecundity [18, 19]. Demir et al. [20] found that men’s age was a critical factor for intrauterine insemination (IUI) success, even if they had normal semen parameters. The association between age and sperm DNA damage was observed for several years. Aging men showed a significantly higher percentage of sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) [21, 22]. Although the average age of qualified sperm donors increased after the COVID-19, it was still less than 30 years old, which is below the natural biological threshold for optimal male fertility potential that most researches have shown [23].

We also found that the proportion of qualified sperm donors with lower education levels increased significantly after the COVID-19 outbreak. Studies found that parental educational attainment was associated with offspring’s health, personality, and innate immune system regulation [24,25,26]. Both genetics and the early living environment of children account for these associations, but sperm donors do not have an impact on the living environment of their offspring. It is uncertain whether the development of offspring is affected by the educational attainment of sperm donors. It is necessary for human sperm banks to be aware of sociodemographic changes among sperm donors after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although studies reported that people experienced great psychological stress and lifestyle changes that adversely affect semen quality [9,10,11] during the COVID-19 pandemic, no decline in semen quality of uninfected men was found. However, chronic stressors negatively affect both natural and specific immunity in humans [27]. Therefore, future studies with specific questionnaires and tests on immune system function, such as leukocyte numbers and levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [28], are warranted to shed more light on COVID-19 and reproductive health of uninfected men.

Research published since the COVID-19 outbreak has focused on the effects of COVID-19 on semen quality and hormone levels, but the results are controversial [29, 30]. According to a multicenter study, the overall andrological health of COVID-19 patients does not seem to be compromised 3 months after recovery [31]. We focused on semen quality of uninfected men after the COVID-19 outbreak by comparing the semen parameters of uninfected sperm donors. No decline in semen quality of sperm donors was observed in our study. In addition, available evidence showed that cryopreserved semen was free of SARS-CoV-2 and was safe for use [32, 33]. Therefore, there is no need for human sperm banks to consider the quality and safety of cryopreserved semen after the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study has some limitations. First, we lacked questionnaire data (e.g., psychological state and lifestyle changes) from sperm donors; therefore, we cannot provide strong evidence regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic-related stress and lifestyle changes on semen quality of uninfected men. Second, the sperm donors were different donors before and after the COVID-19. Third, our findings may only illustrate the situation in one region of China because the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic may vary from place to place. Further studies are required to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

No decline in semen quality of uninfected men was observed after the COVID-19 pandemic in Shandong, China. There is no concern about the quality and safety of cryopreserved semen in human sperm banks after the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the pandemic is constantly recurring and future studies with specific questionnaires and tests on immune system function are warranted to shed more light on COVID-19 and reproductive health of uninfected men.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- AID:

-

artificial insemination with donor sperm

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- IFN:

-

interferon

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- IUI:

-

intrauterine insemination

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SDF:

-

sperm DNA fragmentation

References

Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, Hruska V, Nixon M, Ma DWL, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian families with Young Children. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352.

Hu Z, Lin X, Chiwanda Kaminga A, Xu H. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on Lifestyle Behaviors and their Association with Subjective Well-Being among the General Population in Mainland China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e21176. https://doi.org/10.2196/21176.

Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental Health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017.

Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (London England). 2020;395(10224):565–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80.e278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.

Wang Z, Xu X. scRNA-seq profiling of human testes reveals the Presence of the ACE2 receptor, a target for SARS-CoV-2 infection in Spermatogonia, Leydig and sertoli cells. Cells. 2020;9(4):920. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040920.

Holtmann N, Edimiris P, Andree M, Doehmen C, Baston-Buest D, Adams O, et al. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in human semen-a cohort study. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(2):233–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.05.028.

Gacci M, Coppi M, Baldi E, Sebastianelli A, Zaccaro C, Morselli S, et al. Semen impairment and occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in semen after recovery from COVID-19. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(6):1520–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deab026.

Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad P-G, Mukunzi JN, McIntee S-E, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 295: 113599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and Associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Qin F, Song Y, Nassis GP, Zhao L, Dong Y, Zhao C, et al. Physical activity, screen time, and Emotional Well-Being during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145170.

Nordkap L, Jensen TK, Hansen AM, Lassen TH, Bang AK, Joensen UN, et al. Psychological stress and testicular function: a cross-sectional study of 1,215 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2016; 105(1): 174–187 e171-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.016.

Gaskins AJ, Afeiche MC, Hauser R, Williams PL, Gillman MW, Tanrikut C, et al. Paternal physical and sedentary activities in relation to semen quality and reproductive outcomes among couples from a fertility center. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(11):2575–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu212.

Liu K, Li Y, Zhang G, Liu J, Cao J, Ao L, et al. Association between mobile phone use and semen quality: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2014;2(4):491–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00205.x.

World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. 2010.

Fifield A. Travel Ban Goes into Effect in Chinese City of Wuhan as Authorities Try to Stop Coronavirus Spread. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/nine-dead-as-chinese-coronavirus-spreads-despite-efforts-to-contain-it/2020/01/22/1eaade72-3c6d-11ea-afe2-090eb37b60b1_story.html. Accessed 1 Sept 2020.

Humm KC, Sakkas D. Role of increased male age in IVF and egg donation: is sperm DNA fragmentation responsible? Fertil Steril. 2013; 99(1): 30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.024.

Hassan MA, Killick SR. Effect of male age on fertility: evidence for the decline in male fertility with increasing age. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(Suppl 3):1520–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00366-2.

Kidd SA, Eskenazi B, Wyrobek AJ. Effects of male age on semen quality and fertility: a review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(2):237–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s00150282(00)01679-4.

Demir B, Dilbaz B, Cinar O, Karadag B, Tasci Y, Kocak M, et al. Factors affecting pregnancy outcome of intrauterine insemination cycles in couples with favourable female characteristics. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(5):420–3. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2011.569780.

Paoli D, Pecora G, Pallotti F, Faja F, Pelloni M, Lenzi A, et al. Cytological and molecular aspects of the ageing sperm. Hum Reprod. 2019; 34(2): 218–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey357.

Gill K, Jakubik-Uljasz J, Rosiak-Gill A, Grabowska M, Matuszewski M, Piasecka M. Male aging as a causative factor of detrimental changes in human conventional semen parameters and sperm DNA integrity. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1321–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2020.1765330.

Martínez E, Bezazián C, Bezazián A, Lindl K, Peliquero A, Cattaneo A, et al. Sperm DNA fragmentation and male age: results of in vitro fertilization treatments. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2021;25(4):533–9. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210018.

Barroso I, Cabral M, Ramos E, Guimarães JT. Parental education associated with immune function in adolescence. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(3):444–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz229.

Lindeboom M, Llena-Nozal A, van der Klaauw B. Parental education and child health: evidence from a schooling reform. J Health Econ. 2009;28(1):109–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.08.003.

Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Robins RW, Terracciano A. Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: an intergenerational life span approach to the origin of adult personality traits. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017;113(1):144–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000137.

Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(4):601–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601.

Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res. 2014;58(2–3):193–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0.

Corona G, Vena W, Pizzocaro A, Pallotti F, Paoli D, Rastrelli G, et al. Andrological effects of SARS-Cov-2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-022-01801-x.

Navarra A, Albani E, Castellano S, Arruzzolo L, Levi-Setti PE. Coronavirus Disease-19 infection: implications on Male Fertility and Reproduction. Front Physiol. 2020;11:574761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.574761.

Paoli D, Pallotti F, Anzuini A, Bianchini S, Caponecchia L, Carraro A, et al. Male reproductive health after 3 months from SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicentric study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022; 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-022-01887-3.

Huang C, Zhou SF, Gao LD, Li SK, Cheng Y, Zhou WJ, et al. Risks associated with cryopreserved semen in a human sperm bank during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42(3):589–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.11.015.

Paoli D, Pallotti F, Nigro G, Aureli A, Perlorca A, Mazzuti L, et al. Sperm cryopreservation during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(5):1091–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-020-01438-8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all sperm donors for their participation.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2702905); Research Unit of Gametogenesis and Health of ART-Offspring, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (No. 2020RU001); Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (No. 2018YFJH0504); Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (No. ZR2020MH065), and Taishan Scholars Program for Young Experts of Shandong Province (No. tsqn201909195).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW, WL and HJ conceived and designed the study. ZW drafted the manuscript. WL, HJ, SJ, CL, and ZH revised the drafts. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Reproductive Medicine Ethics Committee, Hospital for Reproductive Medicine Affiliated to Shandong University (No. 2020-67). Informed written consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Wang, L., Sun, J. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on semen quality of uninfected men. Basic Clin. Androl. 33, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-022-00180-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-022-00180-w