Abstract

Background

Urbanization process around the world has not only changed the patterns of land use, but also fragmented the habitat, resulting in significantly biodiversity loss. Urban rivers, serve as one of the natural corridors in urban ecosystems, are of importance for urban ecosystem stability. However, few studies have been done to explore the relationship between vegetation and pollinators in urban river segments. In this study, two urban streams in the city of Chongqing were selected as the study area, riparian vegetation, butterflies and bees were investigated along all four seasons of a year to illustrate the spatial and temporal distribution patterns. Simultaneously, the ecological functions of the river corridor were analyzed.

Result

In this study, 109 plant species belonging to 95 genera of 39 families were recorded; the number of sampled species for butterflies and bees were 12 and 13, respectively. The temporal and spatial patterns of species diversity among vegetation, butterfly, and bee are different, but the trends of variation among them are similar between the two streams. Bees were found to be more closely correlated with native flowering plants in riparian zone, rather than with cultivated riparian vegetation.

Conclusions

The native riparian vegetation in urban rivers plays an important role in urban biodiversity conservation by serving as a corridor. This study provides data supporting the protection of the remaining natural patches and restoration of damaged habitats in the city. The survey has accumulated data on native riparian vegetation and pollinators in urban rivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human settlements and activities have converted pristine natural areas for urbanization and agricultural purposes [1]. In urban areas, urban development has become increasingly domesticated ecosystems and landscapes around the world [2,3,4,5], which results in habitat fragmentation [6, 7]. In the process of urban development, urban landscape has undergone large-scale changes [8, 9]. In the past decades, rapid urbanization throughout the world have caused extensive loss of biodiversity [10]. Studies on urban biodiversity and ecosystem services demonstrated that the ecosystem consequences of local species loss are as quantitatively significant as the direct effects of several global change stressors [11, 12]. The changes of land use that expressing degraded physical, chemical, and biological conditions in urban significantly damage the ecosystem service functions, i.e., microclimate, recreation, stress reduction and habitat quality for biodiversity [13]. One of the most prominent examples is the reduction of urban vegetation caused by urbanization, which may further lead to the reduction of pollinators [14]. Therefore, conservation and restoration of the urban ecosystem are of importance for urban sustainability [15].

Pollinators, i.e., bees and butterflies, are essential for the reproduction of many plant species, providing vital ecosystem services to various ecosystems on the earth [16]. Plant–pollinator interaction is usually driven by abiotic factors, i.e., habitat loss and fragmentation may alter pollinator visitation to vegetation by causing declines in pollinator populations and changes in pollinator community composition. These processes can affect pollination function, especially for plant species dependent upon a particular pollinator [17]. In urban ecosystems, the area of natural vegetation decreases while simultaneously, cultivated vegetation increases. The ecosystem services can be assessed by linking the vegetation data matrix with pollinators, thus, the vegetation succession driven by humans can be analyzed via this linkage [17].

As in many species communication rely highly on natural vegetation as habitat, the reduction in the connectivity these species have been observed frequently with the intensive fragmentation in urbanization process [6, 12]. Urban river and the corresponding riparian zones, ranging from several kilometers to a few tens of kilometers, are important natural wildlife corridors [18]. The high quality of corridors is benefit for moderating some of the adverse ecological effects of habitat fragmentation induced by urbanization process. However, urban rivers are susceptible to severe habitat degradation and pollution in the past decade [19], and their ecological function on linking the fragmented habitats is neglected. Conservation, restoration and rehabilitation of the urban river can not only benefit to the river ecosystem itself, but also establish the network for biodiversity connections [20]. Reports showed that maintaining and restoring watershed vegetation corridors in urban landscapes can aid efforts to conserve freshwater biodiversity [18]. Therefore, as wildlife corridors, urban riparian habitat may provide many ecological functions than we expect [21].

In the current study, we investigated riparian vegetation, bees and butterflies along two urban stream longitudinal, located in the city of Chongqing, China. The aim of the study was to illustrate the relationship between plant and pollinator within urban stream corridors. We hypothesized that the pattern of riparian vegetation and pollinators is closely correlated, and simultaneously, the riparian native (or authigenic) plants are considered to be more corresponded to pollinators. To this end, the spatial and temporal distribution patterns of vegetation and pollinators along with the urban river gradients were investigated, and simultaneously, analyzed their interactions via cluster analysis. Finally, the impact of urbanization on river corridors as shown by vegetation and pollinators, and conservation strategies of riparian ecological functions are discussed.

Materials and methods

Field investigation

In the current study, two urban streams (Qingshui stream and Phoenix stream) which are located at Shapingba district of Chongqing (Fig. 1) were selected, according to the study by Rollin in other areas [22]. The Qingshui stream (QS) and Phoenix stream (PS) both originate from the Gele mountain with lengths of 15.9 km and 7.1 km, respectively [19]. Along the stream longitudinal, 5 sampling sites at the riparian zone of the QS and 4 sampling sites for PS were set up, of which 3 transects with length of 50 m along the stream were involved within each site [23]. We used the method of Wu et al. with modification based on the reality situation of the study area to indicate 3 classes of anthropization for the current study [24]. The information of the sampling sites is summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Pollinators

We conducted 11 times of field investigations between April and December 2019, covering four seasons of a year. The investigations were between 10:00 and 17:00 of a day, and only during good weather [25]. The bees and butterflies were net-captured for 30 min in each transect during the course of each investigation. We stored all captured bees and butterflies for later identification. Bees are identified by body characteristics such as mouth parts, eyes (ocellus and compound eyes) and wings (forewing and hindwing), while butterflies are identified by characteristics such as wing size, shape and pattern [25]. In addition, we perform observation approach for those species that were hard for capturing but could be identified immediately. We identified all specimens to the highest taxonomic level possible, and for more difficult specimens we allocated them to morphospecies.

Vegetation

Concerning the vegetation survey, the vegetation survey was done four times of a year, representing four seasons. As urban riparian vegetation in the study areas are herbaceous, we selected three 1 × 1 m2 quadrats for investigation within each transect, and the species name, number of individuals and number of flowering vegetation were recorded in each quadrangle [26].

Data analysis

In order to recognize the overall patterns of diversity of riparian vegetation and pollinators, analysis of α-diversity is necessary in the current study. Of which Shannon index represents the diversity of species in a community, Richness indicates the total number of the species in a community, while Pielou index shows a community with perfect evenness. These indices illustrate the diversity pattern from different perspectives [27]. The calculation formulas are as follows:

(1) Shannon–Wiener index

(2) Richness index

(3) Pielou index

where Pi is the ratio of the number of individuals to the total number in group i; ln(Pi) is the natural logarithm of the ratio of the number of individuals to the total number in group i; ln(s) is the natural logarithm of the number of species.

(4) Clustering analysis

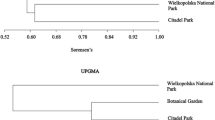

In this study, cluster analysis was used to study the similarity among nine sample sites of the two streams. First, the difference analysis between the two streams was carried out. If there is no significant difference, the two streams were combined for cluster analysis. In other case, cluster analysis for the steams was performed independently. The cluster analysis was calculated according to Jaccard index of the β diversity [27].

All experimental data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 25, USA). When the assumption of homogeneity of variance was met, one-way ANOVA was used to investigate the differences on spatial and temporal distributions. In other case, the Kruskal–Wallis H test was employed. Pearson correlation was used to analyze the relationship between pollinators and vegetation at the 95% confidence level.

Results

Species composition of pollinators and riparian vegetation

In this study, a total of 110 plant species belonging to 93 genera of 36 families were investigated within the river banks of the two streams. In QS, the number of species was up to 70, which belong to 61 genera and 27 families, while that in PS were 71 species, 64 genera, 28 families (Additional file 1: Table S2), respectively. The composition of plant species between QS and PS varied with seasonal changes. Overall, the richness and abundance of riparian plant in the streams are similar, whereas, the composition of plant species varied significantly due to the fact that only 31 species co-occurred within the twos.

The number of collected butterflies was up to 726, which belonged to 5 families, 10 genera and 11 species (Additional file 1: Table S3). Of which, the butterflies were obtained in QS belonged to 10 species of 9 genera and 5 families. The dominant species were Pieris rapae, Pseudozizeeria maha, and Symbrenthia lilaea, with a relative abundance of 35.96%, 25.62%, and 16.75%, respectively. The number of butterflies in PS was 8 species, 7 genera and 4 families, which the dominant species were P. rapae (57.53%) and P. maha (23.29%). The captured bees in QS amounted to 227, which belong to 10 species and 4 families. The bees sampled in PS were 13 species, belonging to 4 families (Additional file 1: Table S3, Figs. S1–S4). Among which, the Apis cerana was pre-dominated in QS with the proportion up to 88.60%. The proportion A. cerana in PS was 32.56%, followed by Vespa vulgaris (11.63%).

Temporal and spatial patterns of species diversity

The highest Shannon–Wiener and Pielou indices of bees along the QS longitudinal were found at QS1, which were significantly higher than that in the other sites of QS, while the richness of bees did not vary significantly along the stream longitudinal (Fig. 2a–c). Unlike bees, the patterns of butterflies and riparian vegetation did not vary distinctly along the QS longitudinal (Fig. 2d–i). There was no significant difference in the diversity of bees, butterflies and vegetation among the four PS study sites (Fig. 3).

The richness of bee in QS varied with the seasons, the highest one was observed in spring, then the value decreased with time. In contrast, Shannon–Wiener and Pielou indices only changed slightly (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the high richness of bee in PS were found in spring and summer. The other two indices showed no significant seasonal fluctuation (Fig. 4d). The patterns of butterfly diversity in QS and PS varied distinctly along the season. The butterfly diversity peaked in spring and summer, and decreased rapidly in autumn and winter (Fig. 4b and e). Regarding the riparian vegetation, the temporal patterns in QS and PS were different, in which a decrease trend from spring to winter was found in QS while the increase trend was obtained from PS (Fig. 4c and f).

The similarity and correlation analysis

The results of cluster analysis are shown in Fig. 5, indicated that for bees, the habitats in downstream of QS was similar to PS, and the species distribution in upper and middle reaches of QS was categorized as a group (Fig. 5a). Regarding butterfly, the pattern of butterfly was clustered into five categories (Fig. 5b), implying that the habitat heterogeneity was more complex than that for bees. Concerning vegetation, the vegetation distribution similarity of PS sites was slightly higher than that of QS sites (Fig. 5c). Overall, there was no obvious commonality among the distribution of bee, butterfly and vegetation.

There was no significant correlation between bees and vegetation in both rivers (Fig. 6a, b). Likewise, the correlation between butterflies and vegetation in QS was not closely, but that for butterfly richness and vegetation diversity index in PS was remarkable (p < 0.05). In QS, the richness and quantity of bee were significant correlation with the native flowering vegetation richness (p < 0.01) and abundance (p < 0.05). However, this was not found for between butterfly and native flowering vegetation. In contrast, the richness of bee was significantly correlated with the abundance of native flowering vegetation (p < 0.05), and the richness of butterfly was significantly correlated with the abundance of native flowering vegetation in PS (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6c, d).

Discussion

Effects of urbanization on river corridor

Urbanization alters the matrix and patch of natural landscape of the city, making differences between natural and planted vegetation patch. The urban diversity changed by urbanization in Chongqing had been studied for a decade, which mainly focused on butterfly and vegetation dynamics along with the urbanization gradients. Yan (2006) reported that even in city park with relatively high plant diversity, the butterfly richness still less than those in natural vegetation of suburbs [28]. These results were quite different from that in Europe, where cities have strong potential to provide natural and semi-natural habitats for different groups of pollinators [29]; whereas, the reason of different linkages between urban vegetation and pollinator could be the different garden management measures, variations on the human activities, and as well as species differences between the two regions.

The composition and distribution of vegetation patches are important to migration of animals. Natural vegetation is usually considered as ecological corridor, which connects with other vegetation strips to create migration routes and provide shelter for animals [30]. Scott et al. (2010) showed that the activity and feeding behavior of pipistrelle bats were closely correlated with the quality of riparian buffer zones [31]. Similar, Villemey et al. (2018) reported that linear transportation infrastructure verges constitute a habitat and/or a corridor for insects [32]. Gray et al. (2022) indicated recently that the important use of riparian buffers in oil palm plantations for forest-dependent dung beetle species [33]. Furtherly, fauna could even adapt to alternation of landscape corresponds to the fluctuation of the flood [34]. Hence, complex ecological processes inherent to intact riverine landscapes are reflected in their biodiversity [34]; whereas, questions still exist on what the pattern of diversity will be and do the riparian zone functional during the changes on the riverine.

Human interruptions to the dynamics of pollinators along riversides are mainly from changing the riparian plant community properties [35]. Although a total of 26 pollinators were found in QS and PS, of which 6 were unique to PS. the dominant species between the two rivers were different. In the QS, the dominant species ranged from 2 to 4, but that for PS were higher. This indicated that the vegetation patches in PS were suitable for most pollinators. Our study found that there was an obvious difference on the distribution of pollinators between QS and PS. Our study found that there was an obvious difference on the distribution of pollinators between QS and PS. The richness of pollinators in QS was significantly lower than that in PS, while the abundance of pollinators in QS was significantly higher than that in PS. As a result, the original normal distribution characteristics of pollinators become low abundance and large number distribution characteristics. On the one hand, this pattern may be caused by indirect interference of human activities, which made the habitats of QS and PS suitable for different plant growth. QS runs almost across the city, which made the microclimate of QS more suitable for some disturbance resistant plants [36]. This was why Humulus scandens, a highly adaptable plant, can be found on every site in QS. Except for the lower reaches, PS were within the city. Thus, during the investigation, the seasonal dominant plants in PS were, e.g., Senccio oldhamianus in spring, Galinsoga parviflora in summer, Clinopodium chinense in fall, and Cardamine leucantha in winter), and Humulus scandens was rarely been found. On the other hand, it might be due to the direct interference of human activities. The vegetation in many sites of these urban rivers has been destroyed. For example, the vegetation of QS3 was destroyed by the used of herbicides in summer. The vegetation of QS5 has also been damaged due to riparian engineering construction, while in PS, the downstream reaches were strongly disturbed by human activities. This was also the reason why in the cluster analysis, the sampling spots in the lower reaches of both QS and PS were similar. In contrast, the vegetation patterns in the upper and middle reaches of the PS were relatively stable. A possible reason could be the variation on the riparian habitat between the two streams, which provides different ecological quality for different species. In QS, riparian area was seriously disturbed by human activities, in particular in sites of the middle reaches (QS2 and QS3), while in PS, the downstream reaches were strongly disturbed by human activities, because these reaches were within the tourist site. These factors lead to the destruction of vegetation patches in rivers, since the damaged vegetation patches decrease many ecological functions of riparian ecosystem, one of which was the interruption of river corridors. If only plant species diversity were studied, no differences between patches would be found, because most of the vegetation patches destroyed were a reduction in the number of individual species (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Implications for urban management and development

Biodiversity conservation in urban ecosystem, in particular for those rapid urbanization cities, is vital for maintenance ecosystem functions. Actions that maintain large contiguous greenspace in the landscape and establish native plants would support the conservation of bees and wasps [30]. Non-native plant species together with managed vegetation may have powerful effects in urban habitats via changes in community-level plant phenology and consequent changes in pollinator phenology [17]. Study has shown that bees and hoverflies were more frequently captured in the remnant native habitat, while beetles (Coleoptera), butterflies/moths (Lepidoptera) were more frequently observed in the urban residential regions in Melbourne, Australian [34, 37]. The bumble bee abundance increased with local floral abundance, besides, not the tree species but weedy margins and weedy plant species provide important resources to bumble bees [38]. This is in line with bee species, whose richness was found to be positively but nonlinearly related to grassland habitat area [39]. The quality of corridors can alter pollinator behavior, i.e., times of visiting, frequencies, etc., and thus further affect the vegetation succession. The overall hedgerow connectedness of a landscape is therefore important both to bumblebee movement and to those plants which depend on bumblebees for pollination services [40].

Concerning river corridor, there was a positive correlation between fragment size and orchid bee species richness and abundance in riparian zone in an urban matrix of southwestern Brazilian Amazonia [41]. Small populations of Lychnis flos-cuculi along an urban river may still exchange pollen due to pollinator movements, and might therefore be regarded in management planning as potential connecting components between populations [42]. Overall, the studies presented above have shown the importance of native vegetation and corridor for pollinators in urban ecosystem. Conservation remnant natural habitat along the river corridor is critical for species migration, i.e., invertebrates, birds, and thus the urban ecosystem function, i.e., diversity conservation, can be effectively improved [43].

Conclusions

In the process of urban development, the question of maintaining biodiversity is one of the main challenges. This study provides an insight for the development of landscape pattern in cities. The native riparian vegetation in urban rivers with adaptation to local climate environments, are better for biodiversity conservation, such as pollinators. The bees and butterflies were closely correlated with flowering vegetation along the riparian zone, showing the corridor functions which can help for species migration and connectivity. The city ecological corridor network could be established with different urban rivers. In addition, protecting the remaining natural patches and restore damaged habitats, for instance, by natural based solutions, are highly recommended [44]. Although the current study clarified the importance of urban rivers as corridors for bees and butterflies, whether it is important for other pollinators is also necessary, which should be done in the future study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- QS:

-

Qingshui stream

- PS:

-

Phoenix stream

References

Xia C, Zhang A, Yeh AGO (2021) The varying relationships between multidimensional urban form and urban vitality in Chinese megacities: insights from a comparative analysis. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 112:141–166

Burke BM (2002) Who sprawls most? How growth patterns differ across the U.S. Popul Environ 23:428–434

Jürgen B, Salman Q (2011) Urban sustainability, urban ecology and the Society for Urban Ecology (SURE). Urban Ecosyst 14:313–317

Wang J, Zhou W, Yu W, Li W (2019) A multiscale analysis of urbanization effects on ecosystem services supply in an urban megaregion. Sci Total Environ 662:824–833

Kremer P, Hamstead Z, Haase D, McPhearson T, Frantzeskaki N, Andersson E, Kabisch N, Larondelle N, Lorance Rall E, Voigt A, Baró F, Bertram C, Gómez-Baggethun E, Hansen R, Kaczorowska A, Kain J-H, Kronenberg J, Langemeyer J, Pauleit S, Rehdanz K, Schewenius M, van Ham C, Wurster D, Elmqvist T (2016) Key insights for the future of urban ecosystem services research. Ecol Soc 21:29

Gibb H, Hochuli DF (2002) Habitat fragmentation in an urban environment: large and small fragments support different arthropod assemblages. Biol Conserv 106:91–100

Zhang Y, Chang X, Liu Y, Lu Y, Wang Y, Liu Y (2021) Urban expansion simulation under constraint of multiple ecosystem services (MESs) based on cellular automata (CA)-Markov model: Scenario analysis and policy implications. Land Use Policy 108:105667

Zhang A, Li W, Wu J, Lin J, Chu J, Xia C (2020) How can the urban landscape affect urban vitality at the street block level? A case study of 15 metropolises in China. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci 48:1245–1262

Zhang A, Xia C, Chu J, Lin J, Li W, Wu J (2019) Portraying urban landscape: a quantitative analysis system applied in fifteen metropolises in China. Sustain Cities Soc 46:101396

Del Tredici P (2010) Spontaneous urban vegetation: reflections of change in a globalized world. Nat Cult 5:299–315

Hooper DU, Adair EC, Cardinale BJ, Byrnes JE, Hungate BA, Matulich KL, Gonzalez A, Duffy JE, Gamfeldt L, O’Connor MI (2012) A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486:105–108

Wu J (2014) Urban ecology and sustainability: the state-of-the-science and future directions. Landsc Urban Plan 125:209–221

Gómez-Baggethun E, Gren Å, Barton D N, Langemeyer J, McPhearson T, O’Farrell P, Andersson E, Hamstead Z, Kremer P (2013) Urban Ecosystem Services. In: Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: challenges and opportunities. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 175–251

Prendergast KS, Ollerton J (2021) Plant-pollinator networks in Australian urban bushland remnants are not structurally equivalent to those in residential gardens. Urban Ecosyst 24:973–987

Luederitz C, Brink E, Gralla F, Hermelingmeier V, Meyer M, Niven L, Panzer L, Partelow S, Rau A-L, Sasaki R, Abson DJ, Lang DJ, Wamsler C, von Wehrden H (2015) A review of urban ecosystem services: six key challenges for future research. Ecosyst Serv 14:98–112

Ramos SE, Schiestl FP (2019) Rapid plant evolution driven by the interaction of pollination and herbivory. Science 364:193–196

Harrison T, Winfree R, Evans K (2015) Urban drivers of plant-pollinator interactions. Funct Ecol 29:879–888

Urban MC, Skelly DK, Burchsted D, Price W, Lowry S (2006) Stream communities across a rural-urban landscape gradient. Divers Distrib 12:337–350

Chen Z, Zhu Z, Song J, Liao R, Wang Y, Luo X, Nie D, Lei Y, Shao Y, Yang W (2019) Linking biological toxicity and the spectral characteristics of contamination in seriously polluted urban rivers. Environ Sci Eur 31:1–10

Guimarães LF, Teixeira FC, Pereira JN, Becker BR, Oliveira AKB, Lima AF, Veról AP, Miguez MG (2021) The challenges of urban river restoration and the proposition of a framework towards river restoration goals. J Clean Prod 316:128330

Hall DM, Steiner R (2019) Insect pollinator conservation policy innovations: lessons for lawmakers. Environ Sci Policy 93:118–128

Rollin O, Pérez-Méndez N, Bretagnolle V, Henry M (2019) Preserving habitat quality at local and landscape scales increases wild bee diversity in intensive farming systems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 275:73–80

Luppi M, Dondina O, Orioli V, Bani L (2018) Local and landscape drivers of butterfly richness and abundance in a human-dominated area. Agric Ecosyst Environ 254:138–148

Wu T, Zha P, Yu M, Jiang G, Zhang J, You Q, Xie X (2021) Landscape pattern evolution and its response to human disturbance in a newly metropolitan area: a case study in Jin-Yi metropolitan area. Land 10:767

Buchholz S, Gathof AK, Grossmann AJ, Kowarik I, Fischer LK (2020) Wild bees in urban grasslands: urbanisation, functional diversity and species traits. Landsc Urban Plan 196:103731

Schmidt KJ, Poppendieck H-H, Jensen K (2013) Effects of urban structure on plant species richness in a large European city. Urban Ecosyst 17:427–444

Martínez-Sánchez N, Barragán F, Gelviz-Gelvez SM (2020) Temporal analysis of butterfly diversity in a succession gradient in a fragmented tropical landscape of Mexico. Glob Ecol Conserv 21:e00847

Yan H, Yuan X, Liu W, Deng H (2006) Butterfly diversity along a gradient of urbanization: Chongqing as a case study. Biodivers Sci 14:216–222

Daniels B, Jedamski J, Ottermanns R (2020) A “plan bee” for cities: Pollinator diversity and plant-pollinator interactions in urban green spaces. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0235492

Zajac Z, Sedzikowska A, Maslanko W (2021) Occurrence and abundance of Dermacentor reticulatus in the habitats of the ecological corridor of the Wieprz River, Eastern Poland. Insects 12(2):96

Scott SJ, McLaren G, Jones G, Harris S (2010) The impact of riparian habitat quality on the foraging and activity of pipistrelle bats (Pipistrellus spp.). J Zool 280:371–378

Villemey A, Jeusset A, Vargac M, Bertheau Y, Coulon A, Touroult J, Vanpeene S, Castagneyrol B, Jactel H, Witte I, Deniaud N, Flamerie De Lachapelle F, Jaslier E, Roy V, Guinard E, Le Mitouard E, Rauel V, Sordello R (2018) Can linear transportation infrastructure verges constitute a habitat and/or a corridor for insects in temperate landscapes? A systematic review. Environ Evid 7:2047–2382

Gray REJ, Rodriguez LF, Lewis OT, Chung AYC, Ovaskainen O, Slade EM (2022) Movement of forest-dependent dung beetles through riparian buffers in Bornean oil palm plantations. J Appl Ecol 59:238–250

Robinson CT, Tockner K, Ward JV (2002) The fauna of dynamic riverine landscapes. Freshw Biol 47:661–677

Gregg JW, Jones CG, Dawson TE (2003) Urbanization effects on tree growth in the vicinity of New York City. Nature 424:183–187

Yao R, Luo Q, Luo Z, Jiang L, Yang Y (2015) An integrated study of urban microclimates in Chongqing, China: historical weather data, transverse measurement and numerical simulation. Sustain Cities Soc 14:187–199

Winfree R, Griswold T, Kremen C (2007) Effect of human disturbance on bee communities in a forested ecosystem. Conserv Biol 21:213–223

Fussell M, Corbet S (1992) Flower usage by bumble-bees: a basis for forage plant management. J Appl Ecol 29:451–465

Turo KJ, Gardiner MM (2021) Effects of urban greenspace configuration and native vegetation on bee and wasp reproduction. Conserv Biol 35:1755–1765

Shakeel M, Ali H, Ahmad S, Said F, Khan KA, Bashir MA, Anjum SI, Islam W, Ghramh HA, Ansari MJ, Ali H (2019) Insect pollinators diversity and abundance in Eruca sativa Mill. (Arugula) and Brassica rapa L. (Field mustard) crops. Saudi J Biol Sci 26:1704–1709

Reeher P, Lanterman Novotny J, Mitchell RJ (2020) Urban bumble bees are unaffected by the proportion of intensely developed land within urban environments of the industrial Midwestern USA. Urban Ecosyst 23:703–711

Hinners SJ, Kearns CA, Wessman CA (2012) Roles of scale, matrix, and native habitat in supporting a diverse suburban pollinator assemblage. Ecol Appl 22:1923–1935

Oliver TH, Heard MS, Isaac NJB, Roy DB, Procter D, Eigenbrod F, Freckleton R, Hector A, Orme CDL, Petchey OL, Proenca V, Raffaelli D, Suttle KB, Mace GM, Martin-Lopez B, Woodcock BA, Bullock JM (2015) Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions. Trends Ecol Evol 30:673–684

Nesshover C, Assmuth T, Irvine KN, Rusch GM, Waylen KA, Delbaere B, Haase D, Jones-Walters L, Keune H, Kovacs E, Krauze K, Kulvik M, Rey F, van Dijk J, Vistad OI, Wilkinson ME, Wittmer H (2017) The science, policy and practice of nature-based solutions: an interdisciplinary perspective. Sci Total Environ 579:1215–1227

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was finally funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 51809024), the Chongqing Science and Technology (No: cstc2018jszx-zdyfxmX0007), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No: 2020CDJQY-A016) and the Vebture & Innovation Support Program for Chongqing Overseas Returnees (No: cx2020064 and cx2019110).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZLC, XZ, LXZ, YXW planned and conceptualized the study; XZ conducted the data collection of bees; LXZ conducted the data collection of butterflies; YXW conducted the data collection of vegetation; XZ, LXZ, YXZ performed statistical analyses and wrote the first draft; XZ, BD, MRN, YS and ZLC edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The habitat profile of the Sampling sites. Table S2. List of vegetation in the Sampling sites. Table S3. List of pollinators in the Sampling sites. Figure S1. A joint analysis of species diversity of pollinators and vegetation in QS. Figure S2. A joint analysis of species diversity of pollinators and vegetation in PS. Figure S3. A joint analysis of species diversity of pollinators and flowering vegetation in QS. Figure S4. A joint analysis of species diversity of pollinators and flowering vegetation in PS.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Zhang, L., Wang, Y. et al. Pollinators and urban riparian vegetation: important contributors to urban diversity conservation. Environ Sci Eur 34, 78 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00661-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00661-9