Abstract

Background

River damming inevitably reshapes water thermal conditions that are important to the general health of river ecosystems. Although a lot of studies have addressed the damming’s thermal impacts, most of them just assess the overall effects of climate variation and human activities on river thermal dynamics. Less attention has been given to quantifying the impact of climate variation, damming and flow regulation, respectively. In addition, for rivers that have already faced an erosion problem in downstream channels, an adjustment of the hydroelectric power plant operation manner is expected, which reinforces the need for understanding of flow regulation’s thermal impact. To fill this gap, an air2stream-based approach is proposed and applied at the Włocławek Reservoir in the Vistula River in Poland.

Results

In the years of 1952–1983, downstream river water temperature rose by 0.31 ℃ after damming. Meanwhile, the construction of dam increased the average annual water temperature by 0.55 ℃, while climate change oppositely made it decreased by 0.26 ℃. In addition, for the seasonal impact of damming, autumn was the most affected season with the warming reached 1.14 ℃, and the least affected season was winter when water temperature experienced a warming of 0.1 ℃. The absolute values of seasonal average temperature changes due to flow regulation were less than 0.1 ℃ for all the seasons.

Conclusions

The impacts of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river water temperatures can be evaluated reasonably on the strength of the proposed methodology. Climate variation and damming led to general opposite impacts on the downstream water temperature at the Włocławek Reservoir before 1980s. It is noted that the climate variation impact showed an opposite trend compared to that after 1980s. Besides, flow regulation below dam hardly affected downstream river water temperature variation. This study extends the current knowledge about impacts of climate variation and hydromorphological conditions on river water temperature, with a study area where river water temperature is higher than air temperature throughout a year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

River water temperature is one of the most important physical indicators of the aquatic system. It controls many physical and biogeochemical processes in the waterbody, such as the biogeochemical turnover rates [38], and the photosynthesis and respiration processes of aquatic species [42]. Almost all the aquatic species have specific water temperature ranges for survival. Abrupt changes of the thermal conditions will impact their production and development [4, 10, 15, 16, 22, 43]. Thus, studying the thermal dynamics of rivers is of great significance.

Due to climate change and anthropogenic activities, river thermal dynamics in many regions have undergone tremendous changes [1, 9, 14, 28, 44, 49]. River damming, as one of the main human interventions to the river systems, plays a vital role in reshaping the river thermal conditions. Generally, damming changes the thermal dynamics of river in two aspects [41]. First of all, the presence of dam itself changes thermophysical properties both in the reservoir and downstream river reach, affecting the thermal interaction between river and atmosphere. Secondly, it affects the heat exchange resulting from water entering and leaving the river reach through flow regulation below dam. It is noted that different kinds of flow regulation also have different impacts on the erosion of downstream river channel [12]. This makes the decision-making of dam flow regulation even harder when some of its impacts remain unknown. Thus, understanding the influence of flow regulation on thermal dynamics is undoubtedly helpful for decision-making of dam flow regulation. Many studies have focused on the damming’s thermal impact issue [3, 5, 19, 20, 23,24,25,26, 32, 36, 39, 40, 45, 46]. However, most of these studies assessed the overall effects of climate variation and human activities (e.g., damming) on river thermal dynamics, and few studies attempted to quantify the impact of climate variation and damming separately, especially the individual impact of flow regulation. Therefore, it is of interest to further decide the roles of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation in the overall effects.

The Vistula River is the largest and longest river in Poland, and the 9th longest river in Europe. The Włocławek Reservoir in the Vistula River is the largest reservoir in Poland [18]. A lot of studies have been conducted for this reservoir, addressing issues, including the impacts of damming on hydrochemistry and plankton [21], zooplankton structure [31], fish migration [2], suspended sediments transport [11], and flow regimes alteration and riverbed erosion [12]. However, to our best knowledge, no publication has reported the impacts of damming and flow regulation on river thermal dynamics. To fill this research gap, we use modeling approach to quantify the individual effect of climate variation, damming and reservoir water management operation on Vistula River water temperature.

There are many river water temperature models available, including simple statistical models [7, 17, 29, 34], machine learning models [13, 35, 51], hybrid statistically physically based air2stream model [41], and complex process-based deterministic models [47, 48]. The hybrid air2stream model was employed as previous studies have shown that the air2stream model is simple to implement, and outperforms both the statistical models and machine learning models [33, 50]. Moreover, it requires less input data (daily water temperature, air temperature, and discharge) compared with the fully process-based deterministic models. For the Vistula River, these data are readily available.

The objective of this study is to quantificationally evaluate the individual impact of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on water thermal dynamics in the Vistula River. To achieve the objective, the study entails as follows: (1) reconstruction of river water temperature in pre-dam period and post-dam period based on the air2stream model; (2) setting a series of scenarios to investigate individual impact from climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river water temperature; and (3) making a comparison of the results to that assessed by Cai’s method [5] to demonstrate the validity of the improved research design. A quantitative assessment of the damming impacts and flow regulation impacts on downstream river water temperature provides reference for sustainable river/reservoir management and will benefit dam removal studies as well, which becomes more and more popular in recent years [8, 37].

Methods

Study area and data sources

The Vistula River has a length of 1047 km, and a basin area of nearly 200 thousand km2. The majority of its drainage area belongs to Poland (87%), and the rest locates at Belarus, Ukraine, and Slovakia (Fig. 1a) [27]. The construction of the Włocławek Reservoir on the Vistula River was initiated in 1962 and completed in 1970. The reservoir was flooded between March 1969 and August 1970. Among Polish reservoirs, it ranks first in area (70 km2) and second in volume (376 mln m3). It is a typical valley type lowland reservoir, with an average depth of 5.5 m (maximum 13 m), a length of 55 km, and a width of 2 km [18]. The water level variation is negligible, which does not exceed 1 m annually. And the mean daily variation in water level is up to 0.2 m [18]. The reservoir has multiple functions, including power generation, navigation, flood control, recreation, and water supply for industry and agriculture [12]. The climate is temperate here with its annual precipitation of 450–550 mm (320–350 mm in May–October). In addition, annual mean air temperature is around 8–9 °C [18].

In this study, observed daily water temperature (Tw) and discharge (Q) data from the Włocławek river gauge station (downstream of the dam), and daily air temperature (Ta) data obtained from the nearby meteorological station in Płock were used (Fig. 1b). These data (available from 1952 to 1983) were obtained from the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management—National Research Institute, Poland. The data were divided into two subgroups: (1) pre-dam period (1952–1966 for pre-dam model calibration and validation, and 1952–1961 for results analysis) and (2) post-dam period (1972–1983 for post-dam model calibration and validation, and 1973–1982 for results analysis). Data from 1967 to 1972 were excluded from this analysis to avoid disturbances during the time of dam construction and starting reservoir operation.

Reconstruction of river water temperature

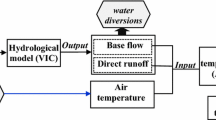

To reconstruct river Tw in the downstream of the dam, the hybrid statistically physically based air2stream model [41] was used in this study (the source code is available at https://github.com/marcotoffolon/air2stream). Based on the heat balance equation, the model owns an advantage of reflecting the physical process of Tw change without geometrical characteristics of the river reach and specific heat inputs. Specifically, given an unknown volume of the river reach, the variation of Tw in this volume is affected by two terms. One is the heat exchange between the river reach and atmosphere, including shortwave and longwave radiation, and latent and sensible heat fluxes. Another one is the differences in heat flux caused by water entering and leaving the control volume. With a basic assumption that Ta and Tw can be used as a main proxy for all processes related to the heat fluxes exchanged at the river-atmosphere interface [6], Taylor series expansion is used to linearly compute each heat flux term. The final form of the air2stream model is obtained as a single ordinary differential equation linearly depending on Ta, Tw, and Q, which has several parameters to be calibrated. There are 5 versions of the air2stream models, i.e., 3-parameter version, 4-parameter version, 5-parameter version, 7-parameter version, and 8-parameter version. The 8-parameter version is derived from the original heat balance equation that takes into account both the effects of climate variation and flow changes on water temperature, while other versions simplify these factors. In this study, the full 8-parameter version of the model was used:

where Tw is water temperature, Ta is air temperature, θ is the dimensionless discharge, t is time, and ty is the duration of a year; a1–a8 are the eight parameters need to be estimated through model calibration capturing all the local effects.

Two air2stream-based models separately in pre-dam period (1952–1966) and post-dam period (1972–1983) were built based on observed daily data on Ta, Tw, and Q at the Włocławek station. As a general rule, 2/3 of each period series data were used for model calibration and 1/3 for model validation. Thus, data from 1952 to 1961 and 1972–1979 were used for pre-dam model and post-dam model calibration, respectively. Data from 1962 to 1966 and 1980–1983 were used for pre-dam model and post-dam model validation, respectively. The different calibrated parameters in these two models represented the river system thermophysical properties before damming (pre-dam) and after damming (post-dam), respectively. Furthermore, model performance was evaluated using the root mean square error (RMSE) and Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency index (NSE) [40]. The results (measured air and water temperature, discharge, and modeled water temperature) were presented in climatological reference year by averaging across all years the values for each day of the year (29 February of leap year was not considered). In addition, all calculations, including RMSE, NSE, as well as the modeled river water temperature, were derived based on the code in Fortran, and the visualization of the results was obtained through Excel.

Investigation into climate, damming, and flow regulation impacts on river water temperature

Given that the Włocławek Reservoir does not experience any wastewater pollution or exploitation for recreation, the changes of thermal regime in the downstream river reach can be primarily attributed to the dam construction and climate variation [21]. Controlled experiments based on the two calibrated models were designed to delineate the impacts on Tw from climate variation, damming, and flow regulation below dam (different scenarios are shown in Table 1). In detail, the total change of Tw in the post-dam period relative to the pre-dam period at the Włocławek gauge station (ΔTtot) can be obtained as

in which \(\Delta {T}_{\mathrm{tot}}\) represents the overall impacts from climate variation and damming. \({T}_{\mathrm{obs},\mathrm{ pre}}\) and \({T}_{\mathrm{obs},\mathrm{ post}}\) are the observed Tw for the periods before and after damming, respectively.

The Tw changes attributed to climate variation can be evaluated by the following equation:

in which \({\Delta T}_{\mathrm{clim}}\) represents the impacts from the climate variation, in ℃; \({T}_{1}\) is the simulated Tw in scenario 1, with pre-dam model, Ta during post-dam period and Q during pre-dam period; \({T}_{01}\) is the simulated Tw for the period before damming (Table 1).

Similarly, changes from damming can be evaluated by Eq. (4):

where \({\Delta T}_{\mathrm{dam}}\) represents the impacts from damming, in ℃; \({T}_{3}\) is the simulated Tw in scenario 3, with post-dam model, Ta before damming and Q after damming.

Specifically, the impact from flow regulation is to be isolated from the damming impacts. The equation is as follows:

in which, \({\Delta T}_{Q}\) represents the impact from the flow regulation below dam, in ℃; \({T}_{2}\) is the simulated Tw in scenario 2, with pre-dam model, Ta in pre-dam period and Q in post-dam period.

The methodology proposed in this study was also compared against the methodology developed by Cai et al. [5] which evaluated the impact of damming based on the difference between observed Tw and simulated Tw of pre-dam model during post-dam period. And the air2stream-based model built according to Cai’s methodology was called as the pre-dam (Cai) model. It used data in pre-dam period for calibration and data in post-dam period for validation.

Results

Variations of thermal pattern

Inter-annual variation

In the study period, mean annual Ta fluctuated between 6 and 10 °C (Fig. 2a). The highest value of 9.48 °C was observed in 1975 and the lowest value of 6.49 °C in 1980; moreover, increasing variation amplitude of Ta during post-dam period was observed. Also, a slight downward trend was evident in general. The annual Tw variation exhibited a similar pattern to Ta except for a slight upward trend. The annual Tw was higher than Ta about 1–2 °C on average. In addition, during the post-dam period, discharge at the Włocławek station showed an increasing trend due to the flow regulation below dam.

Intra-annual variation

Overall, monthly Ta was below 0 °C in winter (from December to February) while in other seasons it always stayed above 0 °C. It reached the highest in summer about 17 °C during the post-dam period. Except for a few months in spring and winter, Ta decreased almost all year round after damming with the greatest decline in summer (Fig. 2b), and the differences varied from − 1.46 °C to 1.40 °C. In addition, the intra-annual variation amplitude of Ta decreased after damming (Fig. 2b). As for Tw, it showed a similar trend to Ta at intra-annual time scales, but oppositely rose slightly almost in every month after the dam was built (shown in Fig. 2c). Besides, the increase of Tw in spring (March–May) and autumn (September–November) varied from 0.36 to 1.05 °C, which was greater than that in summer (June–August) and winter. River discharge changed moderately at intra-annual time scales with the peak value of 1489 m3/s in spring (during post-dam period) (shown in Fig. 2d). Additionally, an overall increase in river discharge after damming was evident for the other three seasons except the spring. The flow regulation below dam produced a decreased annual peak flow and an increased annual minimum river flow relative to the pre-dam period.

Performance of the air2stream model

As shown in Table 2, the values of RMSE for the pre-dam model, the post-dam model, and the pre-dam (Cai) model during calibration and validation periods (at daily resolution) were 0.92 ℃ and 0.96 ℃, 0.93 ℃ and 1.03 ℃, and 0.90 ℃ and 1.31 ℃, respectively. Furthermore, the values of NSE for the three models during calibration and validation periods were all over 0.97, indicating that the three air2stream-based models were all able to satisfactorily reproduce the thermal dynamics in the corresponding pre-dam period and post-dam period. The parameter details of the pre-dam model, the post-dam model, and the pre-dam (Cai) model are listed in Table 3. When comparing the reproduced river Tw with the actual observations at the Włocławek station, the model performance showed a slight deterioration in validation, especially for the pre-dam (Cai) model (Table 2). For the pre-dam model and the post-dam model, the deterioration in validation was attributed to the model bias. However, for the pre-dam (Cai) model, this was expected that the construction of dam had altered the thermal regime of the downstream river reach as the data used for calibration and validation were separately in pre-dam period and post-dam period. The successful reproduction of natural variation of river Tw using the air2stream model provided the basis for accurately quantifying the separate contributions of climate variation and human interventions (impacts from damming and individual impact from flow regulation below dam) on Tw changes at the Włocławek station after the dam was built.

Quantifying the impacts of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river water temperature

Overall, Tw rose by 0.31 ℃ on average after the construction of dam, and Tw was closely related to Ta in both pre-dam period and in post-dam period (Fig. 3a, b). There was also a strong response of Tw to Ta as the variation trends of Tw during the whole year were almost the same to Ta (Fig. 3a, b). In addition, the presence of dam increased the annual Tw by 0.55 ℃ while climate variation oppositely made it decreased by 0.26 ℃ (Table 4). It is noted that the long-term air temperature variation trend after 1980s showed an opposite rising trend. Therefore, climate variation impact on water temperature might show an opposite rising trend too. Moreover, flow regulation below dam (Fig. 3c) had almost no impact on Tw variation in this study.

In particular, the climate variation effect can be divided into two distinct periods throughout the year. In summer (June–August), the climate variation caused monthly mean Tw to decrease by 0.87 ℃ while caused almost no variation on Tw during the rest seasons of the year, which was consistent with the seasonal variation of Ta between pre-dam period and post-dam period (Fig. 2b). When looking at seasonal changes of Tw due to dam presence, the results showed that autumn (September–November) was the most affected season with the warming reached 1.14 ℃, while the least affected season was winter (December–February) when Tw experienced a warming of 0.10 ℃. The annual evolution of the thermal effects on downstream river Tw associated with overall impacts, climate variation, the presence of dam, and flow regulation are clearly visible in Fig. 3d. It deserves pointing out that ∆Ttot exhibited a similar pattern to ∆Tcli too. In addition, the maximum absolute variations of Tw caused by damming and that induced by climate variation were both around 2 ℃.

As for the results based on Cai’s method (Table 4), it shows that the total variation of Tw is the same to the result calculated by the proposed method in this study. Also, the construction of dam increased the Tw by 0.66 ℃ on average, which is 0.11 ℃ higher than ours. And climate variation made it decreased by 0.27 ℃ on average as well. In addition, when looking at seasonal changes of Tw caused by climate variation and dam presence, the highest variation of Tw attributed to climate variation appeared in summer too, with almost the same value. And for the impact from dam presence, autumn was still the most affected season with the warming reached 0.93 ℃, while the least affected season was winter when Tw experienced a warming of 0.47 ℃. It is noted that the seasonal evolution of the thermal effects on downstream river Tw caused by dam presence shows relatively less differences. In addition, we also analyzed the results at upstream Płock station (Fig. 1). It showed that the inter-annual water temperature variation at Płock station and Włocławek station exhibited a similar pattern. Moreover, the impacts of dam presence on Tw were not significantly different (annual impacts were 0.57 ℃ and 0.66 ℃, separately), even though there was a slight difference in intra-annual impacts.

Discussion

More reasonable results by isolating the impact of flow regulation from damming

The advantage of the approach proposed in this paper is that it can detach the individual influence of flow regulation from the whole thermal impacts resulting from dam presence. Although the air2stream model has been successfully used in many areas of Europe, such as Croatia, Switzerland, and Poland [33, 34, 50], hardly any other examples have been shown for similar studies of the individual effects of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river thermal dynamics. Moreover, the seasonal variation of Tw caused by climate variation and dam presence seems more reasonable when compared with the results based on Cai’s method. In detail, for the seasonal variation of Tw attributed to climate variation, these two methods’ results are almost the same in summer and autumn, while there is a slight difference in winter and spring (Table 4). Even though the difference is only about 0.1 ℃ in winter and spring, the results obtained by our approach are more consistent with the seasonal distribution of air temperature (Figs. 2b, 3d). In contrast, the impact on annual Tw from damming is less prominent, but the intra-annual variation is greater with a more noteworthy maximum value in autumn. Flow regulation effects are included in climate change effects rather than damming effects in Cai’s method [5]. This might account for the differences between the results from the proposed approach and Cai’s method. Since the impacts from flow regulation are very small in this case study, the differences between these results are also slight. However, although the impacts from flow regulation below dam for the Włocławek reservoir are very small, it might be more noticeable in other reservoirs [40], leading to more different results between these two methods.

Warming effect of damming throughout the year

To disentangle the underlying mechanisms that cause the whole year warming effect of damming on downstream river Tw, river thermal pattern and thermal inertia effect are analyzed below. As mentioned before, Tw exhibits a similar variation pattern to Ta at intra-annual time scales (Fig. 2b, c). So does the variation pattern of ∆Ttot to ∆Tcli (Fig. 3d). It is preliminarily assumed that the variation pattern of river Tw in this study area is dominated by Ta. To demonstrate this, thermal pattern of the Vistula River is further analyzed. According to the thermal classification [33], there are two thermal patterns based on the different slope values of the linear regression between Tw and Ta (threshold ≈ 0.55). One is thermally reactive pattern (above threshold) representing a strong response of Tw to Ta. Another one is thermally resilient pattern (below threshold) representing a damped response of Tw to Ta. In our study, the slope values of the linear regression between Tw and Ta during pre-dam and post-dam periods are 0.98 and 1.02, respectively, which are all above the threshold. That indicates the downstream river’s thermally reactive pattern did not change after the dam had been built, and the river remained a strong response of Tw to Ta. In addition, since Tw is higher than Ta almost throughout the whole year, the river is always in the state of heat dissipation regarding the interaction between the river and the atmosphere. With the larger thermal inertia of water stored in the Włocławek reservoir in comparison with that of the downstream river, and the river’s thermally reactive pattern, the downstream river reach will dissipate more heat than that in the reservoir. Thus, the released water always acts as a warming source when participating in the heat exchange of downstream river reach, resulting in a warming effect of damming. The elevated water temperature below some small dams has also been noticed by Lessard and Hayes [22]. In this perspective, the results are different from that of the Three Gorges Dam in the Yangtze River [5]. Also, there is not a significant warming effect of damming in winter compared to that of the Three Gorges Dam because of the different climatic conditions between these two study areas.

Ecological influence induced by flow regulation

The presence of dam changes natural river regime, such as the thermal regime and the hydrological regime, which in turn affects the existing water quality, aquatic habitat attributes, and the general health of river ecosystems [5, 21, 40]. Studies have shown that the change in the manner of the hydroelectric power plant operation has changed the hydrological regime of the Vistula River, leading to the erosion (deepening and narrowing) in the downstream of the river channel [12]. It may cause the unintended consequences of losing habitat variability and river fauna differentiation [30]. Therefore, to improve the downstream channel’s erosion situation, the flow regulation below dam may need to be changed. However, changing the flow regulation below dam may also affect the river’s thermal regime that is related to the health of river ecosystem as well [40]. The changes in the thermal dynamics caused by flow regulation of the Włocławek reservoir have been poorly reported, which makes it difficult to assess the total potential impact of flow regulation on the ecosystem. Thus, the result that the flow regulation of the Włocławek reservoir almost has no significant effect on downstream river thermal dynamics in our study will, hopefully, contribute to set scientific guidelines for water resources managers and aquatic ecologists.

Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a new air2stream-based approach for investigating the impacts of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river water temperature. Apart from the advantage of the air2stream model itself, the advantage of this approach is that it can refine the individual influence of flow regulation in a statistically physical way. By comparing the results based on our proposed method and Cai’s method, it seems that this method can provide more reasonable and useful results for decision-making.

This methodology was used in the Włocławek Reservoir, quantifying the impacts of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river water temperature during the period of 1952–1983. The results revealed that Tw rose after the construction of dam. Specifically, the dam presence increased the Tw throughout the whole year, while climate variation oppositely made it decreased. Also, the annual increase due to damming exceeded the impacts from climate variation. In addition, for the impact of dam presence, autumn was the most affected season while the least affected season was winter. However, flow regulation below dam had almost no impact on Tw variation. This study extends the current knowledge about impacts of climate variation and hydromorphological conditions on river water temperature, and is helpful for sustainable river/reservoir management.

With the limitation of the air2stream model, some factors that may also have an impact on the thermal conditions of the river (e.g., the daily precipitation and ice forming) cannot be taken into account in this study. Besides, we still used an older approach (Particle Swarm Optimization) for the calibration of the air2stream model that may affect its performance. Therefore, further research can be extended to the improvements of the air2stream model and the calibration method.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- T w :

-

Water temperature

- T a :

-

Air temperature

- Q :

-

Discharge

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- NSE:

-

Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency index

References

Arora R, Tockner K, Venohr M (2016) Changing river temperatures in northern Germany: trends and drivers of change. Hydrol Process 30:3084–3096. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10849

Bartel R, Wiśniewolski W, Prus P (2007) Impact of the Włocławek dam on migratory fish in the Vistula River. Fish Aquat Life 15(2):141–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.1077

Bartholow JM, Campbell SG, Flug M (2004) Predicting the thermal effects of dam removal on the Klamath River. Environ Manag 34:856–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0269-5

Bunke D, Moritz S, Brack W, Herráez DL, Posthuma L, Nuss M (2019) Developments in society and implications for emerging pollutants in the aquatic environment. Environ Sci Eur. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0213-1

Cai H, Piccolroaz S, Huang J, Liu Z, Liu F, Toffolon M (2018) Quantifying the impact of the Three Gorges Dam on the thermal dynamics of the Yangtze River. Environ Res Lett 13(5):54016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aab9e0

Caissie D (2006) The thermal regime of rivers: a review. Freshw Biol 51(8):1389–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2006.01597.x

Caldwell J, Rajagopalan B, Danner E (2015) Statistical modeling of daily water temperature attributes on the Sacramento river. J Hydrol Eng 20(5):04014065. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584.0001023

Carlson PE, Donadi S, Sandin L (2018) Responses of macroinvertebrate communities to small dam removals: implications for bioassessment and restoration. J Appl Ecol 55(4):1896–1907. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13102

Chen D, Hu M, Guo Y, Dahlgren RA (2016) Changes in river water temperature between 1980 and 2012 in Yongan watershed, eastern China: magnitude, drivers and models. J Hydrol 533:191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.12.005

Fullerton AH, Torgersen CE, Lawler JJ, Steel EA, Ebersole JL, Lee SY (2018) Longitudinal thermal heterogeneity in rivers and refugia for coldwater species: effects of scale and climate change. Aquat Sci 80:3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-017-0557-9

Gierszewski P (2011) Impact of the Włocławek Reservoir on the conditions for the transport of suspended load. Geomorphol Slovaca Bohem 11(1):28–41

Gierszewski PJ, Habel M, Szmańda J, Luc M (2020) Evaluating effects of dam operation on flow regimes and riverbed adaptation to those changes. Sci Total Environ 710:136202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136202

Graf R, Zhu S, Sivakumar B (2019) Forecasting river water temperature time series using a wavelet–neural network hybrid modelling approach. J Hydrol 578:124115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124115

Hannah DM, Garner G (2015) River water temperature in the United Kingdom. Prog Phys Geogr 39(1):68–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133314550669

Hari RE, Livingstone DM, Siber R, Burkhardt-Holm P, Güttinger H (2006) Consequences of climatic change for water temperature and brown trout populations in Alpine rivers and streams. Glob Change Biol 12(1):10–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01051.x

Hudon C, Armellin A, Gagnon P, Patoine A (2010) Variations in water temperatures and levels in the St. Lawrence River (Québec, Canada) and potential implications for three common fish species. Hydrobiologia 647:145–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-009-9922-6

Jackson FL, Fryer RJ, Hannah DM, Millar CP, Malcolm IA (2018) A spatio-temporal statistical model of maximum daily river temperatures to inform the management of Scotland’s Atlantic salmon rivers under climate change. Sci Total Environ 612:1543–1558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.010

Kaczmarek H, Tyszkowski S, Banach M (2015) Landslide development at the shores of a dam reservoir (Włocławek, Poland), based on 40 years of research. Environ Earth Sci 74(5):4247–4259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-015-4479-3

Kędra M, Wiejaczka Ł (2016) Disturbance of water-air temperature synchronisation by dam reservoirs. WEJ 30(1–2):31–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/wej.12156

Kędra M, Wiejaczka Ł (2018) Climatic and dam-induced impacts on river water temperature: assessment and management implications. Sci Total Environ 626:1474–1483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.044

Kentzer A, Dembowska E, Giziński A, Napiórkowski P (2010) Influence of the Włocławek Reservoir on hydrochemistry and plankton of a large, lowland river (the Lower Vistula River, Poland). Ecol Eng 36(12):1747–1753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.07.024

Lessard JL, Hayes DB (2003) Effects of elevated water temperature on fish and macroinvertebrate communities below small dams. River Res Appl 19(7):721–732. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.713

Liu B, Yang D, Ye B, Berezovskaya S (2005) Long-term open-water season stream temperature variations and changes over Lena River Basin in Siberia. Glob Planet Chang 48(1–3):96–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2004.12.007

Liu Z, Chen X, Liu F, Lin K, He Y, Cai H (2018) Joint dependence between river water temperature, air temperature, and discharge in the Yangtze River: the role of the Three Gorges Dam. J Geophys Res Atmos 123:11938–11951. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD029078

Long L, Ji D, Liu D, Yang Z, Lorke A (2019) Effect of cascading reservoirs on the flow variation and thermal regime in the lower reaches of the Jinsha River. Water 11:1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11051008

Maheu A, St-Hilaire A, Caissie D, El-Jabi N, Bourque G, Boisclair D (2016) A regional analysis of the impact of dams on water temperature in medium-size rivers in eastern Canada. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 73:1885–1897. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0486

Majewski W (2018) Vistula River, its characteristics and management. Int J Hydro 2(4):493–496. https://doi.org/10.15406/ijh.2018.02.00116

Marszelewski W, Pius B (2016) Long-term changes in temperature of river waters in the transitional zone of the temperate climate: a case study of Polish rivers. Hydrol Sci J 61:1430–1442. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2015.1040800

Mohseni O, Stefan HG, Erickson TR (1998) A nonlinear regression model for weekly stream temperatures. Water Resour Res 34(10):2685–2692. https://doi.org/10.1029/98WR01877

Moyle PB, Mount JF (2007) Homogenous rivers, homogenous faunas. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104:5711–5712. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701457104

Napiórkowski P, Kentzer A, Dembowska E (2006) Zooplankton of the lower Vistula River: the effect of Włocławek Dam Reservoir (Poland) on community structure. Verh Internat Verein Limnol 29(4):2109–2114. https://doi.org/10.1080/03680770.2006.11903064

Null SE, Ligare ST, Viers JH (2013) A method to consider whether dams mitigate climate change effects on stream temperatures. J Am Water Resour Assoc 49(6):1456–1472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jawr.12102

Piccolroaz S, Calamita E, Majone B, Gallice A, Siviglia A, Toffolon M (2016) Prediction of river water temperature: a comparison between a new family of hybrid models and statistical approaches. Hydrol Process 30:3901–3917. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10913

Piotrowski AP, Napiorkowski JJ (2019) Simple modifications of the nonlinear regression stream temperature model for daily data. J Hydrol 572:308–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.02.035

Piotrowski AP, Napiorkowski MJ, Napiorkowski JJ, Osuch M (2015) Comparing various artificial neural network types for water temperature prediction in rivers. J Hydrol 529:302–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.07.044

Preece RM, Jones HA (2002) The effect of Keepit Dam on the temperature regime of the Namoi River, Australia. River Res Appl 18:397–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.686

Ryan Bellmore J, Duda JJ, Craig LS, Greene SL, Torgersen CE, Collins MJ, Vittum K (2017) Status and trends of dam removal research in the United States. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Water 4(2):e1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1164

Sharma L, Greskowiak J, Ray C, Eckert P, Prommer H (2012) Elucidating temperature effects on seasonal variations of biogeochemical turnover rates during riverbank filtration. J Hydrol 428–429:104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.01.028

Steel EA, Lange IA (2007) Using wavelet analysis to detect changes in water temperature regimes at multiple scales: effects of multi-purpose dams in the Willamette River basin. River Res Appl 23:351–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.985

Tao Y, Wang Y, Rhoads B, Wang D, Ni L, Wu J (2020) Quantifying the impacts of the Three Gorges Reservoir on water temperature in the middle reach of the Yangtze River. J Hydrol 582:124476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124476

Toffolon M, Piccolroaz S (2015) A hybrid model for river water temperature as a function of air temperature and discharge. Environ Res Lett 10:114011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114011

Uehlinger U, König C, Reichert P (2000) Variability of photosynthesis-irradiance curves and ecosystem respiration in a small river. Freshwater Biol 44:493–507. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00602.x

Verbrugge LNH, Schipper AM, Huijbregts MAJ, Van der Velde G, Leuven RSEW (2012) Sensitivity of native and non-native mollusc species to changing river water temperature and salinity. Biol Invasions 14:1187–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0148-y

Wagner T, Midway S, Whittier J, DeWeber J, Paukert C (2017) Annual changes in seasonal river water temperatures in the Eastern and Western United States. Water 9:90. https://doi.org/10.3390/w9020090

Webb BW, Walling DE (1993) Temporal variability in the impact of river regulation on thermal regime and some biological implications. Freshw Biol 29:167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1993.tb00752.x

Webb BW, Walling DE (1996) Long-term variability in the thermal impact of river impoundment and regulation. Appl Geogr 16(3):211–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(96)00007-0

Yearsley JR (2009) A semi-Lagrangian water temperature model for advection-dominated river systems. Water Resour Res 45:W12405. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007629

Yearsley J (2012) A grid-based approach for simulating stream temperature. Water Resour Res 48:W03506. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011WR011515

Zhu S, Bonacci O, Oskoruš D, Hadzima-Nyarko M, Wu S (2019) Long term variations of river temperature and the influence of air temperature and river discharge: case study of Kupa River watershed in Croatia. J Hydrol Hydromech 67:305–313. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0019

Zhu S, Nyarko EK, Hadzima-Nyarko M, Heddam S, Wu S (2019) Assessing the performance of a suite of machine learning models for daily river water temperature prediction. PeerJ 7:e7065. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7065

Zhu S, Nyarko EK, Hadzima-Nyarko M (2018) Modelling daily water temperature from air temperature for the Missouri River. PeerJ 6:e4894. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4894

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by Yangzhou University (No. 137012144), State Key Laboratory of Hydraulic Engineering Simulation and Safety, Tianjin University (HESS-2121), and the Projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52179073).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RY, XL, and SZ designed the study. SZ coordinated the authors for this research activity. RY carried out the modeling and drafted the manuscript. RY and XL discussed and analyzed the results. SW and XW were responsible for the funding acquisition. SW, XW, XL, SZ, RG, MS, and JD edited the manuscript. MP, MS, and RG contributed to data preparation and provision. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, R., Wu, S., Wu, X. et al. Quantifying the impacts of climate variation, damming, and flow regulation on river thermal dynamics: a case study of the Włocławek Reservoir in the Vistula River, Poland. Environ Sci Eur 34, 3 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00583-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00583-y