Abstract

Background

Despite extensive evidence that exposure to lead from ingested ammunition harms humans and wildlife, and in contravention of European states’ commitments under multilateral environmental agreements to minimize lead emissions, lead in hunting ammunition is still poorly regulated in Europe. The proposed restriction on lead gunshot under the REACH regulation is currently discussed for adoption to protect birds in wetlands from lead poisoning. Based on a subsequent investigation report concluding that additional measures are warranted to control the use of lead ammunition in terrestrial environments, ECHA is preparing a new restriction until October 2020. To help inform this process, we describe REACH management instruments and evaluate the effectiveness and enforceability of different legislative alternatives as well as socio-economic aspects of restricting lead shot in comparison to a total ban. We further discuss how the risks and environmental emissions of lead in rifle bullets can be most effectively controlled by legislative provisions in the future.

Results

Among different management tools, restriction was shown to be most effective and appropriate, since imports of lead ammunition would be covered. The partial restriction of lead gunshot limited to wetlands covers only a minor proportion of all lead used in hunting ammunition in the European Union, leaving multiple wildlife species at risk of being poisoned. Moreover, lead shot will be still purchasable throughout the EU. Within Europe, the costs associated with impacts on wildlife, humans and the environment would be considerably lower when switching to alternative gunshot and rifle bullets.

Conclusion

We argue that there is sufficient evidence to justify more effective, economic, and practical legislative provisions under REACH, i.e., restricting the use and placing on the market of lead in hunting ammunition. The enforcement would be significantly facilitated and hunters could easier comply. A crucial step is to define a realistic phasing-out period and chemical composition standards for non-lead substitutes while engaging all stakeholders to improve acceptance and allow adaptation. Until the total restriction enters into force, Member States could consider imposing more stringent national measures. A total restriction would reduce wildlife poisoning, harmonize provisions of national and European laws, and foster any efforts to decelerate loss of biodiversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Use of lead in Europe

Due to the risks to human health and to the environment associated with lead exposure, restrictions on the use of lead and its compounds can be found in a number of European legal acts on lead [1]. In particular, the phasing out of high production volume uses of lead in the European Union (EU), e.g., lead additives in petrol, has likely contributed to the overall decrease of lead levels. Similar decreasing trends have been detected in humans as shown for instance in students’ blood in Germany between 1981 and 2018 [2] (Fig. 1).

Source: German Environmental Specimen Bank (2018) [2]

Overview of European risk management measures on the use of lead in relation to lead levels (µg/L wet weight) in whole blood from male and female students from Munster, Germany (n: 3614; n per year 65 to 129). Note: the arrows indicate the year of enforcement, but do not mean that there is a causal relation between the legislative acts and the decrease of the blood lead levels.

However, several uses of lead are still not regulated at the European level, including the use of lead in hunting ammunition. Currently, lead and its compounds (EC NO 231-100-4, CAS NO 7439-92-1) are manufactured and/or imported into the EU at the rate of 10,00,000–10,000,000 tons per year [3] and are used in different sectors, primarily in lead–acid batteries [4] (Fig. 2).

Sources: [17]

Estimated annual production volume of lead and lead compounds in Europe. Lead in shot and ammunition indicated comprise uses for military purposes, sport shooting and hunting. Lead shot and lead ammunition are also exported to non-EU countries.

Lead in hunting ammunition

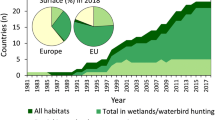

Usually, metallic (also called “mono-valent” or “elemental”) lead is present in gunshot and rifle bullets. Lead ammunition can be classified as lead shot, bullets and airgun pellets. Apart from bismuth, which may contain approximately 0.7% lead [5], metallic lead is currently the only lead-containing compound in gunshot [6]. Based on rather old data by [7], the annual use of lead shot in hunting ammunition in Europe is estimated to lie between 18,000 and 21,000 tons. It is estimated that through hunting at least 357 tons are dispersed into wetlands, and more than 14 000 tons into non-wetlands [6,7,8] (Fig. 3). Most fired lead shot ends up in the environment (99%), while less than 1% of the pellets hit and remain in a killed bird [9]. No exact numbers are available on the amount of lead bullets used by hunters. The European Commission (EC) estimates that the total emission of lead bullets in fifteen Member States, including Hungary, Lithuania and Poland, was around 150 tons in 2005 [8].

Risk management under the REACH regulation

Principles and instruments of REACH

REACH [10] entered into force in June 2007. It stands for Registration, Evaluation Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals. It aims at improving the protection of human health and the environment through better knowledge about the properties and applications of chemicals, faster and more efficient risk assessment, and a clear definition of responsibilities. In general, REACH applies to all chemical substances (including lead). Substances used as plant protection products or biocides either fall under The Biocidal Products Regulation (BPR, Regulation (EU) 528/2012) or the Legislation on Plant Protection Products (but are nevertheless regarded as registered under REACH). Pharmaceuticals are not part of the REACH regulation.

Authorisation and restriction are two of REACH’s core instruments for controlling the risks posed by the sale and use of chemicals. A Member State or the EC can trigger restriction as a regulatory option by preparing a restriction proposal (Annex XV dossier). An authorisation is initiated only for substances of very high concern (SVHC), in order to manage their risks and to trigger substitution by less hazardous substitutions. In contrast, restrictions are usually applied if a chemical poses an unacceptable risk to humans or the environment. Restriction is a more flexible and, in many cases, more effective tool, since it can directly control the manufacture, sale and specific uses of a substance, including imported articles, which are not covered by authorisation.

Authorisation

Authorisation can apply to SVHC that are classified as either carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction (CMR); or as persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT)/very persistent and very bioaccumulative (vPvB); or which cause an equivalent level of concern to substances. Substances identified as a SVHC are included on the Candidate List, which entails immediate obligations for suppliers of the substance, i.e., supplying a safety data sheet, communicating on safe use, responding to consumer requests within 45 days, and notifying ECHA after a maximum period of 6 months if the article they produce contains an SVHC in quantities above one tonne per producer/importer per year and if the substance is present in those articles above a concentration of 0.1% [11].

Substances from the Candidate List are regularly prioritized for inclusion in Annex XIV, which means that they then require an authorisation for manufacture, import and downstream use after a certain sunset date. By now, 32 lead-containing compounds have been identified as SVHC and included in the Candidate List due to their CMR properties. Four lead compounds are listed in Annex XIV [3].

Restriction

According to REACH Art. 3, restriction means any condition for or prohibition of the manufacture, use or placing on the market of a substance. Unlike authorisation a restriction can also restrict substances in products imported into the EU. A restriction is the most appropriate community-wide measure, which shall be assessed using the following criteria according to REACH Annex XV:

- i.

Effectiveness: the restriction must be targeted to the effects or exposures that cause the risks identified, capable of reducing these risks to an acceptable level within a reasonable period of time and proportional to the risk;

- ii.

Practicality: the restriction must be implementable, enforceable and manageable;

- iii.

Monitorability: it must be possible to monitor the result of the implementation of the proposed restriction.

A Member State, or ECHA on request of the EC, can propose restrictions based on an unacceptable risk that needs to be addressed Europe-wide. Firstly, the human and environmental risks are assessed, followed by an evaluation of the effectiveness, practicality, and monitorability of the proposed restriction. The evaluation considers the possibility of alternatives to the risky compounds or techniques, as well as socio-economic aspects of the restriction, and other legal acts already in place.

After submission, the restriction dossier is provided to the wider public for consultation to allow all interested parties to comment. ECHA’s Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) expresses an opinion on whether the proposed restriction is appropriate to reduce human health and environmental risks. In parallel, the Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) evaluates the socio-economic impacts of the restrictions and gives a final opinion. Both opinions are considered when the EC makes a final decision, which then needs to be supported by the Member States in comitology. After the restriction enters into force, the substance is listed in Annex XVII and shall not be manufactured, placed on the market, or used, unless it complies with the conditions of that restriction (REACH Art. 67 (1)) after a certain transition period. Generally, existing restrictions can be amended by widening their scope. Usually it takes 2 to 5 years from initiating the restriction proposal to the enforcement of the restriction.

So far, 68 lead compounds are restricted and listed in REACH Annex XVII [3], whereof four are restrictions on the use of lead compounds in consumer products (Table 1). Due to its neurotoxic effects, particularly on children, the sale of lead to the public has been restricted since June 2018 and its use in the manufacture of jewelry has been restricted since 2013. However, these restrictions do not cover lead in ammunition.

Current restriction activities on the use of lead shot and lead rifle bullets

Over the past decades, ample scientific evidence has been collected to demonstrate that lead poses risks to humans and wildlife. However, metallic lead ammunition is still widely used for hunting and shooting in Europe. It is still not regulated on a union-wide basis, falling instead under a patchwork of national and regional legislations. Today, lead hunting ammunition is one of the largest sources of lead discharged into the environment in Europe, and it places many wildlife taxa at risk of being poisoned [12]. As requested by the European Commission (EC), in 2017 the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) submitted a restriction proposal on the use of lead gunshotFootnote 1 in wetlands,Footnote 2 which was designed to protect waterbirds from the acute and sub-lethal effects of lead exposure via ingestion [6]. There is extensive evidence that exposure to lead from ingested ammunition harms wildlife [6, 13,14,15,16] as well as humans consuming game meat killed with lead ammunition [12, 17,18,19,20]. Many studies have been conducted over the last 60 years demonstrating that lead poisoning from ammunition sources is widespread and causes mortality in many wildlife taxa [6, 8, 13, 14]. Waterbirds feeding in wetlands are particularly likely to be exposed to lead through their ingestion of leaded gunshot. Most recent estimates by [21] suggest that one million individuals from 16 waterbird species die from lead poisoning annually in the whole of Europe and another 3 million waterfowls, including many threatened species, are indirectly killed by sub-lethal poisoning.

The restriction will presumably be adopted by the EC and members states in April 2020. In addition to preparing the restriction proposal, ECHA started collecting information on the potential risks to human health and the environment posed by the use of lead in ammunition (shot and bullets) for hunting in terrains outside wetlands in an investigation report [8]. ECHA concludes that “there is sufficient evidence to justify further measures on the use of lead […] in ammunition (shot and bullets)” [8]. Therefore, the European Commission requested ECHA to prepare an Annex XV dossier on the restriction of placing on the market and use of: (i) lead in gunshot for use in terrains other than wetlands; (ii) lead in other types of ammunition (i.e., bullets or pellets) for use in either wetlands or terrains other than wetlands; and (iii) lead in fishing tackle, to be submitted in October 2020 [22].

Objectives

To support the restriction activities, the present review aims to explain and evaluate the current and future risk management measures on the use of lead in hunting ammunition under the REACH regulation [10]. Furthermore, we examine proposed and potential regulations on lead ammunition in Europe with a focus on environmental protection. We evaluate in detail the proposed restriction on lead gunshot in wetlands, and compare this to a possible future restriction that would extend to non-wetlands as well. As background for this analysis, we describe the principles on which REACH is based, and the risk management instruments and processes that this regulation establishes. We provide an overview of international commitments and exhortations of relevance to the regulation of lead ammunition. The results of a cursory analysis of risk management options are reported, with a focus on expected effectiveness, enforceability, availability of alternatives, and socio-economic issues. We evaluate how the environmental emissions and risks of lead shot and lead-based rifle bullets can be most effectively controlled by future legislative provisions.

Discussion

National, international and EU law and the regulation of lead in hunting ammunition

Regulations on lead shot

Denmark was a pioneer in regulating lead shot used for hunting (details and lessons learned are described by [23]). The USA and Norway enacted laws requiring the use of lead-free shot over wetlands in 1991. Since then, an increasing number of countries have enacted similar restrictions to the same conservation end [24]. California required the use of gunshot for all hunting from 2019 onward [25]. The national approaches to regulating hunters’ lead shot in Europe are as follows: the Netherlands (since 1993) and Denmark (since 1996) have a total ban of lead gunshot use in all types of habitats; 16 members states have a total ban in wetlands and/or for waterbird hunting; and 5 have a partial ban implemented only in some wetlands [24, 26] (Table 2).

Regulations on lead bullets

California is currently the only country which has banned lead in rifle bullets used for hunting [24], while Mauritania prohibits all forms of lead ammunition since 1975 for large game and sport hunting [26]. In Europe the use of lead-based rifle bullets is regulated only in some regions, sites or National Parks in Germany, Italy and Spain in order to avoid contamination of game meat and/or to protect raptors from lead poisoning [24]. For instance, several German states have required use of non-lead rifle ammunition when hunting in state forests, and are examining the implementation of this transition [27]. Details on the regional provisions on the use of lead rifle bullets the European member states are given in [24].

EU conventions and agreements

In its 7th Environmental Action Program [28], the EU calls for strategies to achieve a non‐toxic environment and proposes that “by 2020, chemicals are produced and used in ways that lead to the minimisation of significant adverse effects on human health and the environment”. Allowing hunters to use lead—a well-known SVHC—in hunting ammunition results in direct environmental emissions above 18 000 tons per year in Europe, which is clearly incompatible and inconsistent with the EC’s stated goal of minimizing the use of hazardous chemicals.

Many provisions and agreements of other European directives, conventions and action plans are relevant to lead ammunition and sustainable hunting practice, and make statements regarding the wise or prohibited use and phase out of lead ammunition. These include the ‘Bern Convention’ [28] and the Birds [29] and Habitats Directives [30] (details are given in [31]). The Action Plan of the of the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA, [32]) requires that “parties shall endeavour to phase out the use of lead shot for hunting in wetlands as soon as possible in accordance with self-imposed and published timetables’’ (Annex 3, Action Plan point 4.1.4). The agreed final phase out date was 2017 [33].

Also, the Conference of the parties to the Convention on Migratory Species [34] resolved in November 2014 that all contracting parties, including the European Union, must replace lead ammunition (lead shot and bullets) used for hunting in all habitats with non-toxic substitutes, in order to reduce significant poisoning of migratory birds [34]. So far, no European party complies with the provisions of AEWA and CMS to replace all lead ammunition, even though these are politically binding for contracting countries.

Risk management options for regulating lead shot under REACH

Candidate listing

Recently, Sweden proposed to identify metallic lead as SVHC based on its classification as being toxic for reproduction. After the adoption of this proposal, metallic lead was candidate listed in June 2018. This means that risk information for lead content above 0.1% in articles, including lead shot and lead-containing bullets, must be provided to professional users and be made available on request to consumers (Article 33 in REACH). “Article” is the REACH term for products with a special shape, surface or design, which determines its function to a greater degree than does its chemical composition. REACH would impose significantly different duties and obligations if hunting ammunition were classified as an article and not as a mixture. Specifically, the duty to communicate information (e.g., to respond to consumers request whether a product contains a SVHC) only applies to products defined as articles and not to mixtures. Discussions 2014 among stakeholders, member states’ experts and the EC revealed that there is no EU-wide consensus as to whether lead in cartridges and as the core of bullets is to be regarded as an article or as a mixture. The EC finally specified that ammunition should rather be considered as articles [35]. ECHA supported this view, stating that “ammunition cartridges that are designed to launch a bullet are considered to be articles with an integral substance/mixture (the propellant) because the shape, surface and design of such ammunition cartridges determine their function to a greater degree than do their chemical composition” [36]. For all lead ammunition regarded as articles the SVHC status would theoretically place pressure on manufacturers and distributers to communicate the hazard information to users further downstream. Practically, however, these obligations of better risk communication (which include also providing information to hunters upon request) may remain ineffective as long as the global scientific consensus on the risks from lead is denied by certain hunting and ammunition organizations [31, 37, 38].

Authorisation

If metallic lead were prioritized for inclusion in Annex XIV, all uses of the substance above the concentration limit of 0.1% would require authorisation. This means, that by definition an authorisation would cover all manufacturing and use of lead ammunition, not only the use resulting in the identified risk, i.e., the use of lead ammunition in hunting. However, the authorisation does not cover imported articles. Thus, lead in hunting ammunition would still be accessible for purchase within the EU and this option may in isolation possibly result in increased import of lead ammunition. A combined restriction on imported lead would solve this problem, but would need additional efforts and time. Based on these considerations, authorisation of lead appears practical but less effective than a restriction.

CLP

So far, no harmonized environmental classification (CLP) has been established for lead in its metallic form. Therefore, Denmark proposed in 2017 to classify metallic lead as an aquatic toxic compound (acute 1 and chronic toxic 1). This suggestion for classification is currently in the process of being adopted. However, as the substances are already classified as toxic to reproduction in Category 1A, the additional classification of aquatic toxicity will neither decrease exposure from lead—either from articles or from indirect sources of exposure—nor trigger further risk management measures. As discussed above, it is unlikely that any additional classification or improved risk communication along the supply chain will significantly discourage hunters from buying lead ammunition if lead-based ammunition is still purchasable.

Voluntary waiver

During the past decades it has become obvious that voluntary or partial restrictions on the use of lead ammunition have been largely ineffective, and that national and international legislation is required in order to ensure effective compliance and to create a market for non-toxic ammunition [31]. Though the ecological risks from lead ammunition are well described, there is little evidence that hunters or other stakeholders have made substantial voluntarily progress towards transitioning to lead-free substitutions. Furthermore, a voluntary approach appears unfeasible because it does not provide the legal assurance that manufacturers require to produce, distribute and market new lines of non-lead ammunition [39].

Restriction

A restriction could include the manufacturing, certain uses and/or the placing on the market. A mayor part of lead shot is produced and imported from outside the EU and traded between Member States. Consequently, a restriction covering also imports of lead ammunition for hunting appears to be most effective to implement and faster than authorisation.

REACH restriction of lead shot in wetlands

Due to the well-grounded environmental and human health concerns about exposure to lead shot used for hunting, and in the interest of complying with the aforementioned AEWA and CMS agreements, the EC requested in 2015 that ECHA prepare an Annex XV restriction proposal on lead in shot used in wetlands. Taking into account other legal acts already in place, ECHA concluded that an EU-wide restriction would be the most appropriate measure [6]. However, the restriction covered only “the use of lead and its compounds in shot (containing lead in concentrations greater than 1% by weight) for shooting with a shot gun within a wetland or where spent gunshot would land within a wetland, including at shooting ranges or shooting grounds in wetlands” [6].

During the restriction process, several stakeholders asked why the restriction is limited to wetlands. The EC argued that (1) the scientific knowledge on lethal and sub-lethal effects of lead is most well-established with regard to waterbirds, (2) waterbirds are expected to feed mainly in wetlands, and (3) harmonization of the conditions of use of lead in shot in wetlands is a priority at EU level since national legislation has already been enacted by some Member States or regions to implement the AEWA [40].

In June 2018, ECHA’s scientific committees (RAC and SEAC) adopted ECHA’s proposal that lead gunshot requires restriction in wetlands [41, 42]. Before adoption into law, the restriction needs to be agreed on by the EU REACH Committee representing Member States presumably in April 2020. The restriction will come into operation 36 months after the final adoption by the EC.

Evaluation of the proposed restriction of lead shot in wetlands compared to a full restriction including non-wetlands

Effectiveness

Majority of lead shot emitted to non-wetlands The proposed restriction will minimize the discharge of lead gunshot into wetland environments, which is currently estimated to be 357 t per year. The emission of lead shot in non-wetlands not covered by the current restriction is approximately 14,000 t per year (40 times higher than that in wetlands) (Fig. 3). Thus, the proposed restriction will only reduce a minor part of total lead shot emissions into the environment.

Species feeding in terrestrial areas need protection Many birds, including many non-waterbirds, ingest grit. Shot can be mistaken by birds for stones or grit in areas where hunting takes place [43, 44] (Table 3). In Europe, many bird species feed in both agricultural and terrestrial landscapes, especially outside of the breeding season [45]. The loss of aquatic habitats in recent time likely exacerbated by global warming, will further reduce the availability of wetland habitats for wintering [6] and for foraging, for many bird species. In most remaining high-quality wetlands, strong competition for food will in turn force birds to forage outside the main wetland [6]. More recent research (reviewed by [8, 13, 15]) revealed that the ingestion of lead shot by different wildlife taxa feeding in dryland is widespread and results in annual deaths of 1–2 million waterbirds. Therefore, more targeted action is necessary to address harms from the use of lead shot, including in terrestrial habitats.

Enforceability and practicality

With a partial restriction in wetlands, lead shot will still be distributed throughout the EU and will remain easy to purchase. Field inspections by national authorities to enforce compliance with the restriction appear rather impractical and expensive. A complete restriction of lead gunshot in the entire EU territory (prohibiting the placing on the market and use of any lead gunshot) would be more practical, because it would allow REACH authorities to enforce compliance at the point of sale, e.g., retailers, and not in the field [8]. SEAC [42] concluded that for hunters, a total ban would be easier to comply with compared to the current proposal, because they will not have to identify the wetland area covered by the restriction. Denmark and the Netherlands have shown that total bans can be successfully implemented and enforced [23].

Finally, considering a total restriction on the use of lead shot in all areas, not only wetlands, or a full ban of lead in all hunting ammunition including rifle bullets would have saved time and efforts since now a follow-up restriction process needs to be initiated.

Socio-economic analysis

Costs and benefits The socio-economic analysis under REACH serves as a voluntary “decision-support tool to evaluate the costs and benefits an action will create for society”, i.e., the social costs, by comparing what will happen if this action is implemented as compared to the situation where the action is not implemented [46,47,48]. Within the socio-economic analysis a distinction is made between costs to the private sector (e.g., hunters) and to the society and the environment as a whole. The social cost in Europe of the restriction of lead shot in wetlands is in the order of 30–60 million euros per year, which attribute mainly to EU hunters (including costs for mandatory testing, technical adjustments to shotguns, replacement of shotguns, and the overall cost of more expensive alternative ammunition) [6]. Currently, between 4,00,000 and 1500,000 waterbirds of 33 species are estimated to die every year from ingesting lead shot in EU wetlands [6]. The total social benefits of the proposed restriction, in relation to preventing these deaths, are estimated to be greater than 100 million euros per year [42]. Most recently, Andreotti et al. [21] estimated that the annual cost of releasing captive-bred birds in order to replace the estimated 700,000 wild waterbirds killed by lead poisoning in the EU would be around 105 million euros. These figures establish the proportionality of the suggested restriction as applied only to wetlands.

For terrestrial habitats, only preliminary estimates of costs and benefits exist. 1–2 million birds die annually due to lead poisoning in EU territory [8, 49]. Extrapolating the costs and benefits of a lead restriction from wetlands to non-wetlands, based on the number of birds killed, yields a preliminary estimate of 200 million euros in savings per year. Finally, the enforcement costs would be lower for a total ban than for a partial restriction, because enforcement would be targeted at retailers (which are stationary) rather than at hunters while hunting [42]. The overall benefits from a total restriction are expected to considerably outweigh the costs, and it may therefore be more effective than the proposed partial restriction covering only wetlands.

Availability and suitability of non-lead substitutes The most common non-lead shot type is currently made of steel, although bismuth, tungsten, nickel and copper are also used [50]. It should be noted, that also non-lead substitutes might be toxic to a certain degree when ingested by wildlife or humans. For instance, nickel in lead shot should be avoided as an incidental component because of potential carcinogenicity concerns about such embedded shot in birds and other animals [50]. Bismuth shot contains traces of lead that is shown to be deposited with bismuth in the target animal [5]. Generally, substitutes for lead products must be non-toxic to all wildlife, which assumes that criteria exist for the evaluation of their toxicity [51]. However, the chemical composition of non-lead gunshot used for hunting waterfowl is regulated only in Canada and the USA. Compositional basic criteria for non-toxicity for alternative gunshot have recently been proposed by Thomas [50] and are based on established experimental toxicity protocol by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [52]. Applying these criteria would support the transition to non-lead alternatives since they would facilitate the production and international trade in non-lead products, and promote easier enforcement and user compliance with non-lead standards [50].

Alternatives to lead shot cartridges are available to purchasers in most European countries (22 of 29), and these can be used as effectively as lead shot [53,54,55]. Many studies have demonstrated that steel and other alternatives are as effective as lead ammunition; shooting efficacy and the success of the shot are related to the shooter rather than the ammunition, though shooters may need to adapt to using different ammunition [55]. Reports of positive experiences with the use of non-lead ammunition are increasingly available from countries that have enforced regulations for three decades, including North American countries, the Netherlands, Spain and France [23].

Adaption costs The adaptation cost for an individual hunter of using lead shot alternatives for hunting in wetlands is relatively low (estimated at 50–60 euros per year) compared to the overall budget (estimated to be approximately 3000 euros per year) spent on hunting [6]. The cost of alternatives to lead shotgun ammunition in terrestrial areas would likely be comparable to the cost of using alternatives in wetland hunting. In general, legislation and prices are the driving forces behind public consumption and availability of goods. Thus, a total restriction of lead shot (and lead bullets) would likely result in greater market demand for non-toxic alternatives, and would encourage enhanced technical development, production, and availability of these alternatives [56].

Acceptance Usually, hunters are well-organized at national and international levels, and are represented effectively by industry and politically influential groups, including heads of state and royalty [37]. The polarization and resistance of certain stakeholder groups [31, 37, 38] may be one reason why no union-wide solution has been reached so far, in contrast to restriction of other substances with similar socio-economic importance. However, at least Denmark [23] demonstrated that within a few years of the implementation of the first regulations, hunters and their organizations changed their attitude towards the regulation, with many of them becoming positive and constructive. Since the complete ban of the use, trade and possession of lead shot in Denmark in 1996, there is now full compliance: not a single lead shot was detected in 690 mallards that were examined (Anas platyrhynchos) [5]. Similarly, Valverde et al. [57] recently demonstrated that in Spain, the ban of lead ammunition in wetlands since 2001 has been effective and successful, based on decreasing lead body burden in birds. Assuming a similar change of mind in Europe, the acceptance of a future Europe-wide restriction of lead shot and lead bullets in all habitats appears achievable. This assumption is substantiated by the supportive comments provided by organizations representing hunters and ammunition lobbyists during the public consultation on the restriction [58].

Proposal for solution

The proposed restriction on lead gunshot in and over wetlands, beyond any measures already in place, is a good first step to trigger further action towards the reduction of lead emissions in wetlands and the protection of birds from the acute and sub-lethal effects of lead exposure via ingestion. There is, however, a large body of evidence showing that many different wildlife species can be poisoned by lead ammunition when feeding outside wetlands. In accordance with SEAC and ECHA [6, 42] we argue that the most effective, economic, practical and enforceable measure to limit the identified risks and protect these species completely, would be to enforce a prompt total restriction under REACH on the use of lead shot. To prevent that lead gunshot remains available, since placing on the market and use for non-hunting shooting would be exempted, a restriction of all uses of lead shot, and the placing on the market, would be most efficient. Even though the mandate from the EC addressed the use of lead shot in wetlands only, and a total ban was not further assessed by ECHA, this measure should now be considered during the follow-up restriction activities on lead shot in terrestrial areas. It should be noted, however, that the economic costs and benefits of a total restriction have not been evaluated in detail in the present study but will be assessed during the ongoing restriction activities. Until the total restriction enters into force, Member States could consider making use of paragraph 5 of the restriction of shot in wetlands, that they “may on grounds of human health protection and environmental protection, impose more stringent measures than those set out in paragraphs 1 and 2 [use and possession of lead shot]”.

Outlook—risk management of lead in rifle bullets

Identified risks

Bullets are used for hunting large game such as deer, wild boar and other mammals. Some calibers are also used for smaller game and pest control. In general, the use of lead-based rifle bullets raises well-described concerns similar to those arising from the use of lead shot. The principal concern with lead bullets is that the lead core can disintegrate upon entering the animal and spread fragments into adjacent organs and tissues [15, 59]. Small fragments of the lead core and sometimes of the jacket can be left behind, producing a large cloud of lead particles around the wound channel [59, 60]. Thus, contrary to common belief, the lead dispersed throughout the flesh can only be partly removed by cutting away and discarding tissue from around the wound channel (Krone, personal communication). Higher lead levels and massive dispersion of bullet fragments were recently detected in the flesh of wild boar (Sus scrofa) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) shot with lead bullets, as compared to individuals shot with lead-free ammunition [61, 62]. As lead is considered a non-threshold toxicant, the consumption of contaminated game meat results in risks to humans. Most notably, it poses a risk of harm to neurodevelopment in children and may lead to reduced intelligence quotients in exposed groups.

In addition, many wildlife species are vulnerable to lead exposure from rifle shooting due to the traditional hunters’ practice of removing the entrails of quarry killed in the field and either leaving this on the ground or burying it. The poisoning of scavengers occurs from the ingestion of lead bullet fragments in these discarded gut piles, and in fatally shot-and-lost animals [15, 59]. As a consequence, in Germany lead poisoning from lead in rifle ammunition is the most common cause of death in white-tailed sea eagles (> 20% of animals found dead), which significantly impairs population growth [63]. Due to the widespread use of lead bullets in the EU, similar threats to population levels likely exist for other species but have not yet been analyzed systematically.

Availability and suitability of substitutes

Non-lead rife bullets are broadly available throughout Europe [53, 64]. Most of the non-lead bullets developed to replace lead are made from pure copper or copper-zinc alloy, with or without other metal jacket coatings [71, 72]. They can be divided in monolithic copper- or copper alloy types, occasionally with nickel coating or aluminum or plastic tip and such with jacket–core construction, e.g., a tin core replacing lead [65,66,67]. These new developments allow hunters comparable performance and accuracy compared to traditional lead-based ammunition in most calibers [53, 64, 68,69,70,71]. Lead-free hunting rifle bullets are equal to conventional hunting bullets in terms of killing effectiveness for the target animals (usually roe deer, wild boar and red deer) and thus meet the welfare requirements of killing wildlife without superfluous pain [69]. The recent study by Martin et al. [70] clearly demonstrated that the escape distance of an animal as an indicator for bullet effectiveness depends more on shot placement, shooting distance, hunting method or the age of the hunter than on the material [70]. Similarly, Stokke et al. demonstrated that the relative killing efficiency of lead and copper bullets is similar in terms of animal flight distance after fatal shots [71].

No health risk due to the presence of copper, the principal component of non-lead bullets, and zinc in game meat at typical levels of consumer exposure was found for both types of ammunition [72]. Therefore, it is unlikely that these elements pose health risks to wildlife as it these do also not accumulate in waterbirds [60]. Paulsen et al. showed that most of the available rifle bullet types contain also lead in low concentration (< 0.02% of the bullet mass) and that bullets with nickel plating may release nickel during simulated digestion [66, 67]. Consequently, levels of aluminum, nickel, and lead should be kept as low as possible during bullets’ manufacture to avoid hazardous impact [66]. As with lead shot, no national or international regulation exists for the composition of non-lead rifle ammunition [50, 51]. Only California regulations stipulate that non-lead bullets must contain less than 1% lead by mass [50]. As long as no limits for hazardous substances in non-lead ammunition are determined and as proposed for non-lead gunshot above, these criteria could be used for regulating the composition of rifle ammunition in Europe.

An analysis for the European market concluded that product availability of non-lead rifle ammunition in a wide range of calibers is high in Europe and is suited for all European hunting situations [64] at least 13 major European companies make non-lead bullets for traditional, rare, and novel rifle calibers. It has often been suggested by hunters that the switch to non-toxic alternatives causes extra costs. However, a comparison of retail prices for lead-core and non-lead rifle ammunition of nine commonly used calibers (from .223 to .416) in different weights, types, and brands available across the USA found that prices were generally similar [53, 73]. Similarly, any increase in annual costs for a hunter due to alternative non-lead bullets is likely to be marginal when compared to their overall hunting budget and would not considerably affect individual hunters [31]. It is important to consider that generally, the availability of lead substitutes is a direct consequence of regulation, because only legislation creates the required assurance that non-lead products will be made, distributed and used at the national level [39].

Copper bullets of caliber < 6 mm may not stabilize when fired from the same rifle barrel, which relates to the function of the twist rate of the barrel’s rifling [56, 74]. A transition to the lead-free use of rifle bullets, particularly small calibers, may take longer since hunters will need to change gun barrels to a more appropriate twist rate, or to await the development of denser lead-free bullets [56]. Therefore, a realistic phasing-out period should be determined allowing all actors to comply, by reflecting inter alia the composition and suitability of available alternative ammunition types and the time needed by hunters to change gun barrels and train shooting.

Proposal for risk management of lead bullets

Consistent with the approach of regulating lead in shot, the most practical solution would be that ECHA (as currently done) thoroughly assesses the need for and the implications of a total restriction of lead bullets considering the socio-economic aspects and the effectiveness for human and environmental risk reduction. As with lead shot, a total restriction on the use and placing on the market of lead bullets appears to be the most appropriate management tool. A key factor determining acceptance of any restriction would be the timing and extent of the phase-out period for lead bullets, which should reflect the availability and suitability of substitute ammunition and the creation and application of education-awareness programs, ideally in close collaboration with hunter organizations [56].

Conclusions—moving to further action

Several international and national approaches to overcoming the lead problem have demonstrated that without regulations that apply to all European countries, a joint solution is not achievable. Thus, the proposed union-wide restriction on lead gunshot in wetlands, beyond any current measures, is regarded as a good first step to trigger further action towards the reduction of lead emissions in wetlands and the protection of birds from the acute and sub-lethal effects of lead exposure. However, as demonstrated, such a reduction would still allow multiple wildlife taxa to be poisoned by lead, particularly in terrestrial areas. We conclude that by now there is sufficient evidence to justify further measures against the use of lead in shot. We argue that the most effective, economic, practical and enforceable measure to reduce the risks and environmental costs would be to restrict all uses and the placing on the market of lead shot (not only in wetlands). Such a total restriction would harmonize risk management legislation related to the use of lead gunshot for hunting across EU Member States. In parallel, as similar unacceptable environmental and human health risks of lead in bullets exist, a total restriction on the use of lead rifle bullets under REACH appears most appropriate. As long as no or only partial restrictions will be enforced, Member States could consider imposing more stringent national measures on grounds of human health and/or environmental protection.

A restriction requiring the use of only non-toxic hunting ammunition would need a realistic phasing-out date and the involvement of relevant stakeholder groups to enable adaptation. The latter is guaranteed by procedural obligations within the restriction process under REACH. All comments from stakeholders upon the restriction dossier must be considered, and a socio-economic analysis of the benefits and cost of such a restriction is mandatory.

The obligatory use of lead-free shot and ammunition would have several benefits. It would cause a significant decrease of wildlife poisoning and reduction of the risk to humans consuming game killed with lead. It would further trigger harmonization of national legislation and promote the technical development and production of lead-free substitutes. Finally, in the long-term, a reduction of environmental lead levels will help to decelerate the loss of biodiversity and to protect wildlife populations.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The analysis is based on published articles and reports.

Notes

The term ‘gunshot’ refers to small pellets used in shotguns and excludes rifle ammunition. The term ‘ammunition’ includes both gunshot and rifle ammunition (bullets/projectiles).

‘Wetlands’ are defined according to Article 1(1) Ramsar Convention (1971) applied in 90% of all UN Member States as “areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six meters”.

Abbreviations

- ANNEX XV Dossier:

-

The dossier proposing a restriction under REACH, which contains background information such as the identity of the substance and justifications for the proposed restrictions according to REACH Annex XV

- CLP:

-

Classification, Labeling and packaging of substances and mixtures (CLP Regulation EC 1272/2008)

- CMR:

-

Substances meeting the criteria for classification as carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction (CMR) category 1A or 1B in accordance with the CLP Regulation

- EC:

-

European Commission

- PBT/vPvB:

-

Substances, which are persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) or very persistent and very bioaccumulative (vPvB) according to REACH Annex XIII

- REACH:

-

Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency

- RAC:

-

Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC) at ECHA prepares the opinions of ECHA related to the risks of substances to human health and the environment in the following REACH and CLP processes

- SEAC:

-

Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) prepares the opinions of ECHA related to the socio-economic impact of possible legislative actions on chemicals in the following REACH processes

- SVHC:

-

Substances of very high concern comprising CMRs, PBT/vPvBs or substances on a case-by-case basis, that cause an equivalent level of concern as CMR or PBT/vPvB substances

References

Pohl HR, Ingber SZ, Abadin HG (2017) Historical view on lead: guidelines and regulations. Met Ions Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110434330-013

German environment specimen bank. 2019. UBA: https://www.umweltprobenbank.de/en/documents/10027. Accessed January 2019

ECHA CHEM (2018) information on chemicals. ECHA: https://echa.europa.eu/substance-information/-/substanceinfo/100.028.273. Accessed 23 March 2020

Lead Development Association International (LDAI) (2008) Voluntary Risk Assessment on lead metal, lead oxide, lead tetroxide and lead stabilisers. ECHA: http://echa.europa.eu/fi/voluntary-risk-assessment-reports-lead-and-lead-compounds. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Kanstrup N, Chriél M, Dietz R et al (2019) Lead and other trace elements in danish birds of prey. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 77:359–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00244-019-00646-5

ECHA (2017) Annex XV restriction report on lead in shot and appendix. Proposal for restriction. ECHA, Helsinki, Finland. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/418de695-ad1c-1981-dc73-bd7eb24d54b3. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

AMEC Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited (2012) European Chemicals Agency. Abatement costs of certain hazardous chemicals. lead in shot—final report December (2012). Report for European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Contract No: ECHA 2011/140, Annankatu 18, 00121 Helsinki, Finland. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

ECHA (2018) ANNEX XV Investigation Report. A review of the available information on lead in shot used in terrestrial environments, in ammunition and in fishing tackle. Helsinki, Finland. ECHA: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/13641/lead_ammunition_investigation_report_en.pdf/efdc0ae4-c7be-ee71-48a3-bb8abe20374a

Cromie RL, Newth JL, Reeves JP, O’Brien MF, Beckmann KM, and Brown MJ (2015) The sociological and political aspects of reducing lead poisoning from ammunition in the UK: why the transition to non-toxic ammunition is so difficult. In: Delahay RJ and Spray CJ (ed) Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford, Edward Grey Institute, University Oxford, pp 104–124. http://www.oxfordleadsymposium.info. Accessed 23 March 2020

EC (2006) Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2001/21/EC, The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Commission, ed. Official J Eur Union 30.12.2006. EC: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2013/1386/oj. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

ECHA CHEM (2019) List of substances of very high concern. ECHA: https://echa.europa.eu/substances-of-very-high-concern-identification-explained. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Group of Scientists (2014) Wildlife and Human Health Risks from Lead-Based Ammunition in Europe: a Consensus Statement by Scientists. http://www.zoo.cam.ac.uk/leadammuntionstatement/GroupofScientists. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Fisher IJ, Pain DJ, Thomas VG (2006) A review of lead poisoning from ammunition sources in terrestrial birds. Biol Conserv 131:421–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.02.018

Williams RJ, Holladay SD, Williams SM, Gogal RM (2018) Environmental lead and wild birds: a review. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 245:157–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/398_2017_9

Pain DJ, Mateo R, Green RE (2019) Effects of lead from ammunition on birds and other wildlife: a review and update. Ambio 48:935–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01159-0

Sonne C, Alstrup AKO, Ok YS et al (2019) Time to ban lead hunting ammunition. Science 366:961–962. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz8150

Hunt WG, Watson RT, Oaks JL et al (2009) Lead bullet fragments in venison from rifle-killed deer: potential for human dietary exposure. PLoS ONE 4:e5330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005330

Caspersen IH, Thomsen C, Haug LS et al (2019) Patterns and dietary determinants of essential and toxic elements in blood measured in mid-pregnancy: the Norwegian Environmental Biobank. Sci Total Environ 671:299–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.291

Meltzer HM, Dahl H, Brantsæter AL et al (2013) Consumption of lead-shot cervid meat and blood lead concentrations in a group of adult Norwegians. Environ Res 127:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2013.08.007

Delahay, R.J., and C.J. Spray (2015) Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Edward Grey Institute, the University of Oxford. http://oxfordleadsymposium.info

Andreotti A, Guberti V, Nardelli R et al (2018) Economic assessment of wild bird mortality induced by the use of lead gunshot in European wetlands. Sci Total Environ 610–611:1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.085

ECHA (2019) Call for evidence on a possible restriction on the placing on the market and use of lead in ammunition (shot and bullets) and fishing tackle. October 2019. Background note. ECHA: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/7d96a4a1-c102-8f8b-46e3-96d682b1818c. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Kanstrup N (2019) Lessons learned from 33 years of lead shot regulation in Denmark. Ambio 48:999–1008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1125-9

Mateo R, Kanstrup N (2019) Regulations on lead ammunition adopted in Europe and evidence of compliance. Ambio 48:989–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01170-5

Rendon (2013) Assembly bill no. 711, chapter 742: an act to amend section 3004.5 of the fish and game code, relating to hunting. Legislative Counsel’s Digest. AB 711, Rendon. Hunting: Non-lead Ammunition. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/13-14/bill/asm/ab_0701-0750/ab_711_bill_20130916_enrolled.htm

Avery D, Watson RT (2009) Regulation of lead-based ammunition around the world. In: Watson R, Fuller M, Pokras M, Hunt WG (ed). Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: implications for wildlife and humans. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, pp 161–167

Gremse C, Rieger S (2015) Lead from hunting ammunition in wild game meat: Research initiatives and current legislation in Germany and the EU. In: Delahay RJ and Spray CJ (ed) Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford, Edward Grey Institute, University Oxford, pp 51–56. http://www.oxfordleadsymposium.info. Accessed 23 March 2020

Bern convention. 1979. Convention on the conservation of European wildlife and natural habitats. 1979. https://www.coe.int/en/web/bern-convention. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds. EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32009L0147. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31992L0043

Kanstrup N, Swift J, Stroud DA, Lewis M (2018) Hunting with lead ammunition is not sustainable: European perspectives. Ambio 47:846–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1042-y

AEWA (2018). Agreement on the conservation of african-eurasian migratory waterbirds. 2018. UNEP. https://www.unep-aewa.org/sites/default/files/basic_page_documents/agreement_text_english_final.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020

AEWA strategic plan (2009–2017). UNEP. https://www.unep-aewa.org/sites/default/files/basic_page_documents/strategic_plan_2009-2017_1.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020

Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) (2014) Guidelines to prevent the risk of poisoning to migratory birds UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.23.1.2/Annex2) CMS: https://www.cms.int/en/document/guidelines-prevent-risk-poisoning-migratory-birds-unepcmscop11doc2312annex2

GICAT (2016) Status of ammunition and components of ammunition in the REACH regulation. Professional guidance. Version3. GICAT: http://www.gicat.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/GICAT-REACH-guidance-on-ammunition-version-3-.pdf. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

ECHA (2017) Q & As. Are ammunition cartridges designed to launch a projectile (e.g. a bullet) considered as ‘articles’’ under REACH? ID 159. Modified 22-12-2017. ECHA. https://echa.europa.eu/support. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Arnemo JM, Andersen O, Stokke S et al (2016) Health and environmental risks from lead-based ammunition: science versus socio-politics. EcoHealth 13:618–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-016-1177-x

Arnemo JM, Cromie R, Fox AD et al (2019) Transition to lead-free ammunition benefits all. Ambio 48:1097–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01221-x

Thomas VG (2019) Rationale for the regulated transition to non-lead products in Canada: a policy discussion paper. Sci Total Environ 649:839–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.363

ECHA (2015) Call for evidence: lead in shot. Background note. Helsinki, Finland. ECHA. https://echa.europa.eu/de/previous-calls-for-comments-and-evidence/-/substance-rev/13407/term. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

ECHA (2018) Committee for Risk Assessment (RAC). Opinion on an Annex XV dossier proposing restrictions on lead in gunshot. ECHA/RAC/RES-O-0000006671-73-01/F. ECHA. https://echa.europa.eu/de/previous-consultations-on-restriction-proposals/-/substance-rev/17005/term. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

ECHA (2018) Committee for Socio-economic Analysis (SEAC) Opinion on an Annex XV dossier proposing restrictions on Lead in shot. ECHA https://echa.europa.eu/de/previous-consultations-on-restriction-proposals/-/substance-rev/17005/term. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Pain DJ, Cromie RL, and Green RE (2015) Poisoning of birds and other wildlife from ammunition-derived lead in the UK, In: Delahay RJ and Spray CJ (ed) Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford, Edward Grey Institute, University Oxford, pp 58–84 http://www.oxfordleadsymposium.info. Accessed 23 March 2020

Pain DJ, Fisher IJ, Thomas VG (2009) A global update of lead poisoning in terrestrial birds from ammunition sources. In: Watson RT, Fuller M, Pokras M, Hunt WG (eds) Ingestion of lead from spent ammunition: implications for wildlife and humans. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, pp 289–301

Fox AD, Ebbinge BS, Mitchell C, et al (2010) Current estimates of goose population sizes in western Europe, a gap analysis and an assessment of trends. Ornis Svec 20:115–127–115–127. https://doi.org/10.34080/os.v20.19922

ECHA (2011) Guidance on the preparation of socio-economic analysis as part of an application for authorisation. ECHA, Helsinki. ECHA: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/23036412/sea_authorisation_en.pdf/aadf96ec-fbfa-4bc7-9740-a3f6ceb68e6e. Accessed January 2019

ECHA (2008) Guidance on socio-economic analysis—restrictions. Guidance for the implementation of REACH. ECHA, Helsinki. ECHA https://echa.europa.eu/guidance-documents/guidance-on-reach. Accessed January 2019

Gabbert S, Hilber I (2019) Socio-economic analysis in REACH restriction dossiers for chemicals management: a critical review. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01285-9

Pain DJ, Dickie I, Green RE et al (2019) Wildlife, human and environmental costs of using lead ammunition: an economic review and analysis. Ambio 48:969–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01157-2

Thomas VG (2019) Chemical compositional standards for non-lead hunting ammunition and fishing weights. Ambio 48:1072–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1124-x

Thomas VG, Guitart R (2003) Lead pollution from shooting and angling, and a common regulative approach. Environ Policy Law 33:150–154

USFWS (1997) Migratory bird hunting: revised test protocol for nontoxic approval procedures for shot and shot coating; 50 CFR Part 20; Department of the Interior. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Federal Register 62:63608-63615,Washington, DC

Thomas VG (2013) Lead-free hunting rifle ammunition: product availability, price, effectiveness, and role in global wildlife conservation. Ambio 42:737–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-012-0361-7

Thomas VG (2015) Availability and use of lead-free shotgun and rifle cartridges in the UK, with reference to regulations in other jurisdictions, In: Delahay RJ and Spray CJ (ed) Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford, Edward Grey Institute, University Oxford, pp 125–135. http://www.oxfordleadsymposium.info. Accessed 23 March 202

Kanstrup N, Thomas VG (2019) Availability and prices of non-lead gunshot cartridges in the European retail market. Ambio 48:1039–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01151-8

Kanstrup N, Thomas VG, Krone O, Gremse C (2016) The transition to non-lead rifle ammunition in Denmark: national obligations and policy considerations. Ambio 45:621–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0780-y

Valverde I, Espín S, Navas I et al (2019) Lead exposure in common shelduck (Tadorna tadorna): tracking the success of the Pb shot ban for hunting in Spanish wetlands. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 106:147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.05.002

ECHA (2017) Comments submitted to date on restriction report: Comments and answers to specific information requests. Public Consultation on the Restriction of lead shot over wetlands. Last updated 21/12/2017. ECHA https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/c521de15-e940-dd95-daba-9416a21ca636. Accessed 14 Dec 2019

Krone O (2018) Lead poisoning in birds. In: Sarasola JH et al. (ed) Birds of Prey. Springer Cham, Switzerland, pp 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73745-4_11

Trinogga AL, Courtiol A, Krone O (2019) Fragmentation of lead-free and lead-based hunting rifle bullets under real life hunting conditions in Germany. Ambio 48:1056–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01168-z

Gerofke A, Ulbig E, Martin A et al (2018) Lead content in wild game shot with lead or non-lead ammunition—does “state of the art consumer health protection” require non-lead ammunition? PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200792

Menozzi A, Menotta S, Fedrizzi G et al (2019) Lead and copper in hunted wild boars and radiographic evaluation of bullet fragmentation between ammunitions. Food Addit Contam Part B 12:182–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/19393210.2019.1588389

Sulawa J, Robert A, Köppen U et al (2009) Recovery dynamics and viability of the white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) in Germany. Biodivers Conserv 19:97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9705-4

Thomas VG, Gremse C, Kanstrup N (2016) Non-lead rifle hunting ammunition: issues of availability and performance in Europe. Eur J Wildl Res 62:633–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-016-1044-7

Irschik I, Wanek C, Bauer F, Sager M, Paulsen P (2014) Composition of bullets used for hunting and food safety considerations. In: Paulsen P, Bauer A, Smulders FJM (eds) Trends in game meat hygiene: from forest to fork. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, pp 363–370. ISBN 978-90-8686-238-2

Paulsen P, Bauer F, Sager M, Schuhmann-Irschik I (2015) Model studies for the release of metals from embedded rifle bullet fragments during simulated meat storage and food ingestion. Eur J Wildl Res 61:629–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-015-0926-4

Paulsen P, Sager M (2017) Nickel and copper residues in meat from wild artiodactyls hunted with nickel-plated non-lead rifle bullets. Eur J Wildl Res 63:63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1123-4

Gremse F, Krone O, Thamm M et al (2014) Performance of lead-free versus lead-based hunting ammunition in ballistic soap. PLoS ONE 9:e102015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102015

Trinogga A, Fritsch G, Hofer H, Krone O (2013) Are lead-free hunting rifle bullets as effective at killing wildlife as conventional lead bullets? a comparison based on wound size and morphology. Sci Total Environ 443:226–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.10.084

Martin A, Gremse C, Selhorst T et al (2017) Hunting of roe deer and wild boar in Germany: is non-lead ammunition suitable for hunting? PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185029

Stokke S, Arnemo JM, Brainerd S (2019) Unleaded hunting: are copper bullets and lead-based bullets equally effective for killing big game? Ambio 48:1044–1055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01171-4

Schlichting D, Sommerfeld C, Müller-Graf C et al (2017) Copper and zinc content in wild game shot with lead or non-lead ammunition—implications for consumer health protection. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184946

Thomas VG (2015) Availability and use of lead-free shotgun and rifle cartridges in the UK, with reference to regulations in other jurisdictions. In: Delahay RJ and Spray CJ (ed): Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium. Lead ammunition: understanding and minimizing the risks to human and environmental health. Oxford, Edward Grey Institute, University Oxford, pp 85–97. http://www.oxfordleadsymposium.info. Accessed 23 March 2020

Caudell J, Stopak S, Wolf P (2012) Lead-free, high-powered rifle bullets and their applicability in wildlife management. Human Wildlife Interact 6. https://doi.org/10.26077/qajj-wf35

Acknowledgements

This review article has been prepared within the course of the UBA comments on the REACH restriction of lead shot in wetlands and on the call for evidence for the planned Annex XV dossier on the use of lead in hunting ammunition. We particularly want to acknowledge Deborah Pain for providing information. Furthermore, we want to thank all reviewers for their efforts to peer review the manuscript.

Funding

All funds for the design of the review article and writing the manuscript have been provided by the German Environment Agency (UBA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GT conceptualized and wrote the manuscript. WD and FS supported to further elaborate the manuscript and contributed specific aspects. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Treu, G., Drost, W. & Stock, F. An evaluation of the proposal to regulate lead in hunting ammunition through the European Union’s REACH regulation. Environ Sci Eur 32, 68 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00345-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00345-2