Abstract

Background

Aquatic vegetation has major influence on the local water environment, affecting flow velocities and solute mixing. Extensive research has been conducted on the flow characteristics of vegetated areas, but little is known about solute transport. In this study, Laboratory experiments were carried out to investigate how solute transport is affected by emergent and submerged rigid vegetation.

Results

Vegetation greatly reduces the mean velocity, especially within the vegetated region. Near the bottom, the solute concentration is greater in the dense vegetation than in the sparse vegetation. The vertical distribution of the solute concentration decreases rapidly with the relative water depth. Generally, the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients are less affected by denser vegetation, but both coefficients are strongly influenced by the relative water depth (submerged vegetation height).

Conclusions

A modified function to estimate the longitudinal diffusion coefficients is proposed under both emergent and submerged vegetation conditions, including cases of variable vegetation height. The key parameters (a’ and b’) for the assessment of the lateral diffusion coefficients are improved considering vegetation height. Results in the present paper can be used as efficient and convenient methods to estimate the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients in flow with rigid vegetation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aquatic vegetation is abundant in estuaries, wetlands, and along streams and rivers. It has a major influence on the water environment, affecting flow velocities [1,2,3,4,5], turbulence structures [6,7,8], sediment suspension [9,10,11], and the process of solute mixing [12,13,14,15,16]. Vegetation not only enhances solute mixing and diffusion due to the effects of the plant stem wake [17], but also decreases mechanical diffusion due to the physical obstructions changing the transport path of the solute [18]. The solute diffusion process is also affected by the vegetation density, Reynolds number, and other factors [13, 19, 20]. Thus, a detailed study of solute transport through vegetation is essential to understand the physical processes involved, which will provide important information for proper water environment and resource management.

The effects of vegetation on solute transport have been experimentally studied by many researchers. The lateral diffusion coefficient can be expressed in terms of the plant stalk diameter, the distance between plants (stem density), the flow velocity, and the drag coefficient [19]. The coefficient increases with vegetation density, but the effect disappears when the Reynolds number is higher than 240 [20]. Similar results were obtained by Tanino and Nepf [21], showing that the lateral diffusion coefficient generally increases with increasing vegetation density, while the longitudinal diffusion shows the opposite pattern. Ghisalberti and Nepf [22] found that longitudinal solute diffusion is related to the relative water depth (i.e., the ratio of vegetation height to water depth). Between the vegetation and free flow layers, solute diffusion is influenced by the vortex generated from stem-scale turbulence [23], but it is dominated by large-scale shear dispersion with the increasing relative water depth [24]. Thus, the mechanisms of vegetation-induced solute diffusion are mainly due to the mechanical forces caused by the physical obstruction of vegetation. However, there are also convective processes caused by the uniform distribution of flow velocity and the turbulent diffusion caused by vegetation wake flow [25]; these processes have not been quantified for their influence on solute diffusion. Without these data, the numerical simulation of solute transport through vegetation is limited.

In this study, laboratory experiments were conducted to investigate how solute transport is affected by rigid vegetation and to quantitatively analyze the influence of vegetation on solute diffusion. This study aims to examine the interactions between flow, solute, and vegetation, and to provide important parameters for the numerical simulation of solute transport through vegetation.

Methods

Experimental setup

Laboratory experiments were conducted in a 2.0-m-long and 0.3-m-wide rectangle Plexiglas flume at Tongji University, China (Fig. 1). The current was driven by a pump and circulation system, with a current stabilizer installed at the head of the flume and an energy dissipation fence at the end. The vegetation zone was 1.0 m long and located in the middle of the flume. Stiff wooden cylinders, 8 mm in diameter (d), were used to mimic rigid vegetation, neglecting the movement of natural vegetation (e.g., swaying and bending). The cylinders were placed in holes drilled in the false bottom of the flume. The vegetation conditions are shown in Table 1.

Three inflow discharges (Q = [0.45, 0.67, 0.9] L/s) were applied to each vegetation condition, with a constant water depth (h) of 15 cm. The flow velocities were measured at 13 vertical positions by a Propeller Flow Velocity Meter, which records the average data in a given period of time (10 s in the present experiments). Velocity at each position was collected 3 times and the average value was used for analysis.

The solute discharge system consisted of a peristaltic pump and a backpressure valve. The discharge outlet was placed at section x = 0 at a height of 10 cm (shown in Fig. 1). Non-adsorptive solute dye tracer carmine was discharged at 10.54 mL/s in all tests.

Image processing technology

Image processing technology [26] was used to analyze the solute distribution in the vegetated flow. Two cameras collected the lateral and plan view of the study arena. To avoid outside light disturbance, the setup was surrounded by curtains and internally illuminated by two symmetrically arranged 50 W LED (light-emitting diode) lamps.

Eleven different solute concentrations were used to calibrate the relationship between concentration and image intensity (Table 2). For each concentration, three images were collected to obtain the image intensity, and the average value was used for further analysis (results are shown in Fig. 2). The relationship between solute concentration and image intensity was fit by a power function (Eq. 1), with a correlation coefficient of R2= 0.9618 (C is the solute concentration and I the image intensity).

Equations of diffusion coefficients

The double station linear analytical method is applied to calculate the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients, as shown in Eqs. 2 and 3 [27,28,29].

where x is the longitudinal direction and y the transverse direction; C (x,t) (mg/L) is the solute concentration at the downstream station with distance x (cm) from the injection outlet at time t (min); C (x,y) (mg/L) is the solute concentration at position (x,y); C0 (mg/L) is the initial concentration; W (mg) is the mass of the release solute; A (cm2) is the cross-section area; DL (cm2/s) and Dy (cm2/s) are the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients; q (mL/s) is the solute inflow velocity; u (cm/s) is the average flow velocity of the section; h (cm) is the water depth; and k (s−1) is the first-order reaction of the tracer rate constant.

Results

Mean velocity affected by vegetation

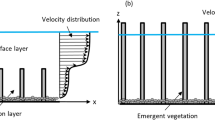

Figure 3 shows the vertical distribution of the mean velocity (u) in cases A–H at section x = 20 cm. Comparing the results of trials with Q = 0.45 L/s and Q = 0.90 L/s revealed that the vertical distributions of the u gradients are greater with larger inflow discharge. The inflection points generally occur around the vegetation tops, and the inflection points only occur in the upper layers of the tops when the vegetation height is 5 cm. Vegetation greatly reduces the mean velocity, especially within the vegetated region, and the flow velocity decreases with increasing vegetation density. Due to the relatively low variation in the volume fraction of vegetation (ϕ = 0.016 and 0.008), the change in velocity is minimal (shown in Fig. 3a–f). In the emergent conditions, the velocity is lower near the bottom and higher in the upper layers than that in the submerged cases.

Solute concentration affected by vegetation

The vertical profiles of the time-averaged concentrations (C) at section x = 20 cm, normalized by the max concentration at x = 0 cm (Cmax= 1000 mg/L), are displayed in Fig. 4. The data were obtained from the average values of 150 frames which were continually collected 5 s after the release of the solute. The concentration is greater near the bottom in dense vegetation than in sparse vegetation, due to the stronger blocking effect of the vegetation. The peak concentration decreases from the injection height to the bottom with increasing inflow discharge and vegetation height. This is due to the velocity shear in vegetated flow and the no-flux boundary at the bed, as well as the heavier solute density. The vertical concentration gradients are larger in cases A and B with a 5 cm vegetation height. The concentration decreases more rapidly with lower relative water depth (hv/h), indicating that the solute plume is more diluted and evenly distributed with decreased vegetation height.

Longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients

The calculated longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients are shown in Tables 3 and 4. These results indicate that the flow Reynolds number has a significant influence on the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients. With larger inflow discharge, both coefficients are relatively higher, and with denser vegetation, both coefficients are generally lower. In this study, the stem-Reynolds numbers are always less than 100, so the mechanical diffusion caused by physical obstruction dominates the solute transport process [6].

Figures 5 and 6 show the relationships between the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients and the stem-Reynolds number; both coefficients are proportional to the stem-Reynolds number, and both are affected by vegetation density. Generally, dense vegetation slows the transport of solute, demonstrated by lower longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients, due to the physical obstructions of vegetation. However, opposite patterns are present in cases G and H with varied vegetation height. Previous study [8] has revealed that the vertically varying vegetation density increases the vertical gradient of mean streamwise velocity compared with the emergent uniform vegetation and decreases it compared with the submerged uniform vegetation under unidirectional flow, while the time series of streamwise velocity oscillates relatively stronger and causes higher turbulent kinetic energy affected by the vertically varying vegetation density. The multi-shear layers in trials with varied vegetation height increase the shear- and wake- turbulence, especially in case with higher vegetation density, which accelerates solute mixing and transport.

Discussion

Correlations between longitudinal diffusion coefficients and vegetation features

Nepf [18] proposed an equation to predict the longitudinal diffusion coefficient within an emergent vegetation canopy, using the transport-Reynolds number (Ret) and the vegetation features, as shown in Eq. 4.

where Ret = ud/(v + vt) is the transport-Reynolds number with the rate of lateral wake spreading, which is constant across a wide range of Reynolds numbers for turbulent wakes when the turbulent viscosity (υt) is larger than the molecular viscosity (υ); υt is 0.03 cm2/s according to Nepf [18]; d is the diameter of the vegetation stem; CD is the drag coefficient of the vegetation, determined by stem-Reynolds numbers Red with CD = 1+10R−2/3ed [30]; γ is a O(1) function of Red and γd the length scale of the recirculation zone behind the cylinder [31]; τ is the resident time of the solute, τ = d2/4D and D is a diffusion constant [18].

The longitudinal diffusion coefficients of this study and the predictions from Eq. 4 are compared in Fig. 7. The values agree only in conditions with emergent vegetation, and the average relative error is 6.1% (Fig. 7c). This suggests that the prediction equation is not suitable for submerged vegetation (the average relative error is 134% when hv = 5 cm and 38.6% when hv = 10 cm) or when the vegetation height varied (the average relative error is 18.1%). Although the longitudinal diffusion coefficients are negatively related to vegetation density, DL/ud is proportional to the solid volume fraction (ϕ) due to reduced flow velocity in dense vegetation. Together, these analyses and research by Ghisalberti and Nepf [22] suggest that the relative water depth (the ratio of vegetation height to water depth) is an important factor to estimate the longitudinal diffusion coefficients in vegetated flow.

Equation 5 represents a modified function to estimate the longitudinal diffusion coefficients under emergent and submerged vegetation and with varied vegetation height. The relative water depth of Eq. 4 is used to describe the submergence of vegetation.

where hv′/h is the newly defined relative water depth and hv′ the submerged vegetation height. In conditions with emergent vegetation hv′ = h, and hv′ is the average height of the submerged parts in conditions with varied vegetation height.

Figure 8 shows the comparisons between the longitudinal diffusion coefficients observed in this study and the modified predictions from Eq. 5. The values are consistent in cases with submerged vegetation and varied vegetation height. From the modified function, the average relative error is 7.3% when hv = 5 cm, 4.8% when hv = 10 cm, and 12.8% when vegetation height varied, supporting the use of Eq. 5 to predict the longitudinal diffusion coefficients affected by emergent and submerged vegetation with uniform or varied heights.

Correlations between lateral diffusion coefficients and vegetation features

Jamali et al. [20] conducted experiments to investigate the lateral dispersion of flow with emergent rigid vegetation. The authors proposed an equation to estimate the lateral diffusion coefficient (Eq. 6).

where a and b are constants to be determined, and a and b equal 0.18 and 2157 when ϕ < 0.015, and equal 0.175 and 1035 when ϕ > 0.015, respectively.

The lateral diffusion coefficients of this study were compared to the predictions of Eq. 6 in Fig. 9. There is poor agreement between the experimental results and the predictions for dense and sparse vegetation—the average relative error is 55.3% and 121.7%, respectively, including trials with emergent vegetation (E and F). In Eq. 6, the proposed values of a and b are from Jamali et al. [20], and Dy/ud is inversely proportional to Red due to the influence of u. In this study, Dy/ud is positively related to Red because of the small inflow discharge. Also, Eq. 6 incorporates vegetation features such as the density and stem diameter in the stem-Reynold number, but neglects vegetation height, which is an important factor for flow turbulence and dispersion [22, 24].

To analyze the influence of vegetation height on the lateral diffusion coefficients, the a and b values of Eq. 6 were refitted with the experimental results of this study and denoted as a′ and b′. The best-fitting results of a′ and b′ are provided in Table 5, and a comparison of the experimental results and predictions using the improved constants are displayed in Fig. 10. The experimental results and modified predictions are well-matched; the average relative error is 3.4% when hv = 5 cm, 6.9% when hv = 10 cm, 3.6% when hv = 20 cm, and 7.6% when the vegetation height varied. These results suggest that the lateral diffusion coefficient is sensitive to changes in a′ and b′ both of which are related to vegetation height. The relationships between the a′ and b′ values and the newly defined relative water depths (hv′ /h) are shown in Fig. 11; both a′ and b′ are binomially related to hv′/h.

For the solute transport in free flow without vegetation, there have several empirical equations to assess the longitudinal [32,33,34,35,36,37] and lateral [38, 39] diffusion coefficients. Results in present paper were compared with the results using empirical equations as shown in Table 6. Using the similar experimental condition, the longitudinal diffusion coefficients using empirical equations are in the range of 1.72–341.00 cm2/s, in which the results of proposed method in Eq. 5 fall. The lateral diffusion coefficients using empirical equations are 4.32–9.12 cm2/s, which has the same order as the results using the proposed parameters (Table 5). The methods proposed in the present paper have narrowed the wide range of the coefficients obtained from the empirical equations with a certain degree of accuracy.

Conclusions

Laboratory experiments were carried out in this study to investigate how solute transport is influenced by emergent and submerged rigid vegetation. Vegetation greatly reduces the mean velocity, especially within the vegetated region, and the solute concentration is greater near the bottom in dense conditions due to the blocking effect of vegetation. The concentration peak of the vertical distribution occurs from the injection height to the bottom with increasing inflow discharge and vegetation height, and the solute concentration decreases more rapidly with decreasing relative water depth. Generally, the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients are less affected by denser vegetation than in cases with varied vegetation height. Based on previous research by Nepf [18] and Jamali et al. [20], this study also quantitatively analyzed the influence of vegetation on the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients. Both of the coefficients are affected by the relative water depth (submerged vegetation height). A modified function to estimate the longitudinal diffusion coefficients is proposed for emergent and submerged vegetation conditions, including instances of varied vegetation height, and the values of a′ and b′, key parameters for lateral diffusion coefficients assessment, are improved to consider vegetation height. These methods can be used to estimate the longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients of flow through rigid vegetation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- a and b :

-

Constants used to estimate the lateral diffusion coefficient in Eq. 6

- a’ and b’ :

-

Constants refitted with the experimental results of this study

- A :

-

The cross-section area

- C (x,t) :

-

The solute concentration at the downstream station with distance x from the injection outlet at time t

- C (x,y) :

-

The solute concentration at position (x,y)

- C :

-

The solute concentration

- C 0 :

-

The initial concentration

- C D :

-

The drag coefficient of the vegetation

- C max :

-

The max concentration at x = 0 cm

- D :

-

A diffusion constant

- d :

-

Vegetation diameter

- DL and Dy :

-

The longitudinal and lateral diffusion coefficients

- h :

-

Water depth

- h v /h :

-

Relative water depth

- h v :

-

Vegetation height

- hv’:

-

The submerged vegetation height

- I :

-

The image intensity

- k :

-

The first-order reaction of the tracer rate constant

- LED:

-

Light-emitting diode

- Q :

-

Inflow discharges

- q :

-

The solute inflow velocity

- R 2 :

-

Correlation coefficient

- R ed :

-

Stem-Reynolds numbers

- R et :

-

The transport-Reynolds number

- t :

-

Time

- u :

-

Mean velocity

- u * :

-

Friction velocity

- W :

-

The mass of the release solute

- w :

-

Width of the flume

- x :

-

The longitudinal direction

- y :

-

The transverse direction

- ν :

-

A O(1) function of Red

- τ :

-

The resident time of the solute

- υ :

-

The molecular viscosity

- υ t :

-

The turbulent viscosity

- ∅ :

-

The volume fraction of vegetation

References

Ghisalberti M, Nepf HM (2002) Mixing layers and coherent structures in vegetated aquatic flows. J Geophys Res-Oceans 107(C2):3–11

Zong LJ, Nepf H (2010) Flow and deposition in and around a finite patch of vegetation. Geomorphology 116(3–4):363–372

Leonardi N, Camacina I, Donatelli C, Ganju NK, Plater AJ, Schuerch M, Temmerman S (2018) Dynamic interactions between coastal storms and salt marshes: a review. Geomorphology 301:92–107

Donatelli C, Ganju NK, Zhang XH, Fagherazzi S, Leonardi N (2018) Salt marsh loss affects tides and the sediment budget in shallow bays. J Geophys Res-Earth Surf 123(10):2647–2662

Donatelli C, Ganju NK, Kalra TS, Fagherazzi S, Leonardi N (2019) Changes in hydrodynamics and wave energy as a result of seagrass decline along the shoreline of a microtidal back-barrier estuary. Adv Water Resour 128:183–192

Nepf HM (1999) Drag, turbulence, and diffusion in flow through emergent vegetation. Water Resour Res 35(2):479–489

Neumeier U (2007) Velocity and turbulence variations at the edge of saltmarshes. Cont Shelf Res 27(8):1046–1059

Lou S, Chen M, Ma GF, Liu SG, Zhong GH (2018) Laboratory study of the effect of vertically varying vegetation density on waves, currents and wave–current interactions. Appl Ocean Res 79:74–87

Lopez F, Garcia M (1998) Open-channel flow through simulated vegetation: suspended sediment transport modeling. Water Resour Res 34(9):2341–2352

Sharpe RG, James CS (2006) Deposition of sediment from suspension in emergent vegetation. Water Sa 32(2):211–218

Loder NM, Irish JL, Cialone MA, Wamsley TV (2009) Sensitivity of hurricane surge to morphological parameters of coastal wetlands. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 84(4):625–636

Tsujimoto T (1999) Fluvial processes in streams with vegetation. J Hydraul Res 37(6):789–803

Nepf H, Ghisalberti M (2008) Flow and transport in channels with submerged vegetation. Acta Geophys 56(3):753–777

Okamoto T, Nezu I (2010) Large eddy simulation of 3-D flow structure and mass transport in open-channel flows with submerged vegetations. J Hydro-environ Res 4(3):185–197

Lu J, Dai HC (2016) Effect of submerged vegetation on solute transport in an open channel using large eddy simulation. Adv Water Resour 97:87–99

Lu J, Dai HC (2018) Numerical modeling of pollution transport in flexible vegetation. Appl Math Model 64:93–105

Nepf HM, Sullivan JA, Zavistoski RA (1997) A model for diffusion within emergent vegetation. Limnol Oceanogr 42(8):1735–1745

Nepf HM (2004) Vegetated flow dynamics. Coast Estuar Stud 1:137–163

Serra T, Fernando HJS, Rodriguez RV (2004) Effects of emergent vegetation on lateral diffusion in wetlands. Water Res 38(1):139–147

Jamali M, Davari H, Shoaei F (2019) Lateral dispersion in deflected emergent aquatic canopies. Environ Fluid Mech 19(4):833–850

Tanino Y, Nepf HM (2008) Lateral dispersion in random cylinder arrays at high Reynolds number. J Fluid Mech 600:339–371

Ghisalberti M, Nepf H (2005) Mass transport in vegetated shear flows. Environ Fluid Mech 5(6):527–551

Burke EN, Wadzuk BM (2009) The effect of field conditions on low Reynolds number flow in a wetland. Water Res 43(2):508–514

Murphy E, Ghisalberti M, Nepf H (2007) Model and laboratory study of dispersion in flows with submerged vegetation. Water Resour Res 43(5):1-12

Huang YH, Saiers JE, Harvey JW, Noe GB, Mylon S (2008) Advection, dispersion, and filtration of fine particles within emergent vegetation of the Florida Everglades. Water Resour Res 44(4):1-13

Van EE, Pope P, Balick L, Becker N, David N, Gunaji N, Wells R, Whiteson A (1996) Image processing technology. Office of Scientific and Technical Information Technical Reports

Guo JQ, Zhang Y (1997) Linear graphics method for determining the transverse diffusion coefficient of river. J Hydraulic Eng 1:62–67 (In Chinese)

Wen J, Guo JQ, Zai SH, Wang HS (2008) Linear analytic method for determining water quality parameters of river according to the observation data obtained from two sections. J Hydraulic Eng 39(5):618–622

Fan Y, Shi KB (2013) The tracer experimental method for determining longitudinal dispersion coefficient of nature river. Adv Mater Res 748:1155–1159

White FM (2005) Viscous fluid flow, vol 20. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp 548–550

Gerrard JH (1978) Wakes of cylindrical bluff bodies at low Reynolds-number. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 288(1354):351–382

Elder JW (1959) The dispersion of marked fluid in turbulent shear flow. J Fluid Mech 5(4):544–560

Fischer HB (1975) Discussion of simple method for prediction of dispersion in streams by R.S. Mc Quivey and T.N. Keefer. J Environ Eng Div ASCE 101:453–455

Liu H (1977) Predicting dispersion coefficient of stream. J Environ Eng Div ASCE 103(1):59–69

Seo W, Cheong S (1998) Predicting longitudinal dispersion coefficient in natural streams. J Hydraulic Eng 24(1):25–32

Kashefipour SM, Falconer RA (2002) Longitudinal dispersion coefficients in natural streams. Water Res 36:1596–1608

Li X, Liu H, Yin M (2013) Differential evolution for prediction of longitudinal dispersion coefficients in natural streams. Water Res Manag. 27(15):5245–5260

Li L, Li YL, Chen JF (2003) Experiment on transverse diffusion coefficient in trapezoidal cross section flume. J Tsinghua Univ (Natural Science) 43:1–4 (In Chinese)

Deng ZQ, de Lima JLMP, de Lima MIP (2003) Predicting transverse turbulent diffusivity in straight Alluvial Rivers, Revista Engenharia Civil 16. Universidade do Minho, Braga, pp 43–50

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers, Associate Editor, and Editor for their constructive comments.

Funding

This work was sponsored by the Shanghai Peak Discipline Program for Civil Engineering School, Tongji University (II) (2019010207), National Natural Science Foundation of China (41602244), and Funds for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51961145106).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLou and HL were responsible for conceptualization and methodology; HL and MC designed the experiments; SLou, SLiu, and GZ processed the data; SLou contributed to the original manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, S., Liu, H., Liu, S. et al. Longitudinal and lateral diffusion of solute transport in flow with rigid vegetation. Environ Sci Eur 32, 40 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00315-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-00315-8