Abstract

Background

Primary urethral cancer in males is rare. Clear cell adenocarcinoma is more rare. We report a case in an African male suspected to have a urethral stricture.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man presented in with preceding intermittent haematuria and acute urinary retention. Failed attempts at catheterisation necessitating a suprapubic catheter insertion raised the suspicion of a urethral stricture. Multiple irregular urethral filling defects were seen on a retrograde urethrogram. Urethroscopy revealed obstructing urethral masses. Histology reported clear cell adenocarcinoma.

Conclusion

Primary urethral cancer should be entertained as a differential diagnosis of a urethral stricture in a patient with haematuria, difficult urethral catheterisation and ambiguous urethrogram findings. Cystoscopy and biopsy are essential in the investigative work-up to make the distinction.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Primary urethral cancers are rare and account for less than 1% of all malignancies [1]. They are uncommon in males and are mostly urothelial carcinomas (75%) and squamous cell carcinoma (12%). Only 6% are adenocarcinoma [2]. A review of 142 cases of male urethral cancer revealed no primary male urethral adenocarcinoma [3]. Clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA) involving the male urethra is even more rare [4]. Ten definite cases in males have been reported in the literature, with none emanating from Africa. We report a CCA of the urethra in an adult African male presenting with features suggestive of a urethral stricture.

2 Case presentation

A 66-year-old Nigerian male of Yoruba heritage presented with mixed lower urinary tract symptoms of eight-month duration and intermittent bleeding per urethra. His symptoms culminated in an episode of acute urinary retention. Attempt at urethral catheterisation failed, necessitating suprapubic catheterisation, raising the suspicion of a urethral stricture. He had no prior history of urologic surgery, purulent urethritis or trauma to the pelvis, perineum or external genitalia. At presentation, he was pale. He had no significant peripheral lymphadenopathy. There was no palpable abdominal or groin mass, nor urethral induration. A digital rectal examination revealed an enlarged prostate with benign features.

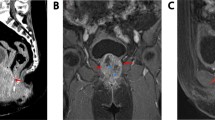

A retrograde urethrogram revealed an incomplete narrowing of the proximal bulbar urethra with elevated bladder neck and multiple filling defects (Fig. 1). His clotting profile was within normal limits. Serum PSA was 4.7 ng/ml. An abdominopelvic ultrasound scan showed a normal liver and kidneys, with a thickened bladder wall and 60 cc prostate with a prominent middle lobe. Urethroscopy showed multiple polypoid masses in the anterior urethra with areas of necrosis and blood clots (Fig. 2). The 24Fr urethroscope could not be advanced beyond the bulbar urethra. Biopsies of the visualised masses were taken. A pelvic magnetic resonance image showed an anterior urethral hyperintensity which did not extend to the corpus spongiosum (Fig. 3a and b). There were no concerning features for prostate malignancy.

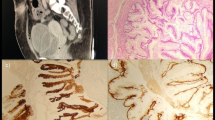

The gross specimen comprised were multiple fragments of greyish white tissue. Cut surfaces of these fragments were greyish white in appearance with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis. The histology showed fragments of fibrocollagenous tissue infiltrated by malignant glands, solid nest of pleomorphic cells and papillary structures. The component cells had large hyperchromatic to vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and abundant clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm on haematoxylin and eosin staining. These clear cells stained positively with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) as shown in Fig. 4. Some hobnail cells were seen lining the lumen of cystically dilated acini containing mucinous material. Mitosis was brisk with abnormal mitotic figures. There were extensive areas of coagulative and haemorrhagic necrosis with mild infiltration by inflammatory cells mainly lymphocytes and neutrophil polymorphs. Immunohistochemical markers to affirm the urethral origin of the tumour such as PAX8 and PSA to rule out an invasive prostate carcinoma were unavailable in our immediate environment.

a Haematoxylin & Eosin, (H&E) × 40: Section shows diffuse sheet of malignant cells with abundant clear to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm b H&E × 400: Section shows clear cells with pleomorphic vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli c Periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) (× 400): Section shows the cytoplasm of the clear cells contain magenta-coloured PAS-positive glycogen

The patient declined the options of a urethrectomy, cystoprostatourethrectomy and/or penectomy. He defaulted from definitive management but presented intermittently with symptomatic anaemia for which he received multiple blood transfusions. Two years after diagnosis, a home visit revealed significant weight loss with poor performance status. The tumour had infiltrated the suprapubic stoma and the scrotal skin was indurated (Fig. 5). Multiple groin lymph nodes were palpable. He died within two weeks of the last review.

3 Discussion

Primary urethral CCA is a rare and aggressive tumour found predominantly in women and may be associated with a urethral diverticulum [5]. The term CCA was proposed by Young and Scully in 1985 due to its histopathological spectrum similar to CCA of female genital tract. It may arise from either Müllerian rests or metaplastic urothelium. [4,5,6]

The main prognostic factors are location and depth of invasion. Anterior lesions tend to be superficial and have a good prognosis. Posterior lesions are deeply invasive and have higher rates of distant metastasis [7]. Compared with other urinary tract malignancies, the prognosis is poor. Patients often present with metastatic or locally advanced disease [5, 8]. Our patient presented with features of locally advanced disease, viz. obstructive symptoms, haematuria and bloody urethral discharge. Periurethral abscess and fistulae have also been documented to occur. [8]

Although our patient had a urethroscopy which shed more light on the diagnosis and ruled out benign urethral stricture as a differential diagnosis, a report from another centre in Southwestern Nigeria showed that only 7 percent of patients with suspected urethral strictures were able to have urethroscopies due to financial and resource-limited challenges [9]. Another report from Ethiopia highlighted the difficulties many Sub-Saharan or low-income nations face with access to endoscopy for routine diagnosis and/or therapeutics [10]. Endoscopic diagnosis is further recommended due to the presentation with visible haematuria [11]. The retrograde urethrogram, which is a cheaper and more readily accessible test in low-income nations, showed multiple filling defects which could have been neoplasms or inadvertent air bubbles, and the urethroscopy served as a complementary investigation to improve accuracy. [12]

Histologically, CCAs typically display tubulocystic, papillary, mucinous, villous and diffuse patterns [2, 13, 14]. Sun et al. [13] reported the papillary variant as the most common, followed by tubulocystic patterns. Typical cytological characteristics of clear cell adenocarcinoma include hobnail cells, flattened cells and cells with abundant clear cytoplasm. These cytologic features should aid in the distinction of CCA from benign nephrogenic adenoma, another rare but benign tumour. [13,14,15,16] CCA of the urethra exhibits positive immunohistochemical staining with PAS, paired box protein (PAX) 2, PAX8, cytokeratin (CK) 7, p16, p53, cancer antigen (CA) 125, cell adhesion molecule (CAM) 5.2, AE1/AE3 and stains negatively with prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), thrombomodulin, oestrogen, progesterone, CK20, p63, cluster of differentiation (CD) 10, polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (CEAp), Wilm’s tumour (WT) 1, alpha foetoprotein (AFP), S-100. [15, 17,18,19]

Due to the rarity of CCA of the urethra, the optimal treatment of the advanced disease is unknown [20]. Our patient declined any form of intervention, thus limiting the contribution of this report to intervention armamentarium. However, the scenario provided a natural history for the untreated case of primary urethral CCA. Cantrell et al. [21]treated their male patient with total pelvic radiation after staging pelvic lymphadenectomy. The patient died 26 months later. Seseke et al. [18] performed total urethrectomy with suprapubic urinary diversion. The patient died 30 months following his surgery. A case series of 15 CCA of various male genitourinary organs included two definite urethral and seven possible prostatic or prostatic urethral origins. This latter set was not included in the sum total of urethral cases reported in this write-up due to the uncertain origin. Therapies used included transurethral resections, targeted therapy with gefitinib, hormonal therapy and nivolumab immunotherapy. Poor prognosis occurred in those with ambiguous origin from the prostatic urethra or the prostate itself [22]. Other noted therapies for male urethral CCA include radical cystoprostatectomy, urethrectomy, bilateral inguinal and pelvic lymph node dissection and ileal conduit urinary diversion with adjuvant chemotherapy [20], partial penectomy with cystoprostatectomy and partial urethrectomy. [23]

There is a dearth of knowledge on the effectiveness of chemotherapy in the treatment of primary urethral CCA. Liu et al. [24] reported a case of metastatic urethral CCA in a male treated with maximal cystoscopic resection of the tumour and palliative systemic therapy (cisplatin and gemcitabine) intermittently for nearly 2 years. Second-line therapy with nab-paclitaxel was ineffective. Two other documented cases had no long-term follow-up. [4, 15]

4 Conclusion

CCA of the urethra is rare in men. It may be a cause of acute urinary retention in an adult male with lower urinary tract symptoms and bloody urethral discharge. Endoscopic investigations are recommended to aid diagnosis and as an adjunct to urethrography. A consensus for the optimal treatment of advanced disease has remained elusive due to paucity of cases.

Availability of data and materials

Relevant de-identified images have been made available.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

Alpha foetoprotein (AFP)

- CAM:

-

Cell adhesion molecule

- CCA:

-

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

- CA:

-

Cancer antigen

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation (CD) 10

- CEAp:

-

Polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid–schiff

- PAX:

-

Paired box protein

- PSA:

-

Prostate specific antigen

- WT:

-

Wilm’s tumour

References

Gatta G, Van Der Zwan JM, Casali PG, Siesling S, Dei Tos AP, Kunkler I et al (2011) Rare cancers are not so rare: the rare cancer burden in Europe. Eur J Cancer 47(17):2493–2511

Yachia D, Turani H (1991) Colonic type adenocarcinoma of male urethra. Urology 37(6):568–570

Melicow MM, Roberts TW (1978) Pathology and natural history of urethral tumors in males review of 142 cases. Urology 11(1):83–89

Gandhi J, Khurana A, Tewari A, Mehta A (2012) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the male urethral tract. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 55(2):245

Mehra R, Vats P, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Udager AM, Roh M, Alva A et al (2014) Primary urethral clear-cell adenocarcinoma: comprehensive analysis by surgical pathology, cytopathology, and next-generation sequencing. Am J Pathol 184(3):584–591

Basiri A, Narouie B, Moghadasi MH, Ghasemi-Rad M, Valipour R (2015) Primary adenocarcinoma of the urethra: a case report and review of the literature. J Endourol Case Report 1(1):75–77

Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, Herr HW (1999) Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology 53(6):1126–1132

Varachhia SA, Goetz L, Persad RNV (2009) Clear cell carcinoma of the male urethra presenting as periurethral abscess with fistulae. J Pelvic Med Surg 15:221–223

Olajide AO, Olajide FO, Kolawole OA, Oseni I, Ajayi AI (2013) A retrospective evaluation of challenges in urethral stricture management in a tertiary care centre of a poor resource community. Nephro-Urology Mon 5(5):974–977

Biyani CS, Bhatt J, Taylor J, Gobeze AA, McGrath J, MacDonagh R (2014) Introducing endourology to a developing country: How to make it sustainable. J Clin Urol 7(3):202–207

Tan WS, Feber A, Sarpong R, Khetrapal P, Rodney S, Jalil R et al (2018) Who should be investigated for haematuria? Results of a contemporary prospective observational study of 3556 patients. Eur Urol 74(1):10–14

Bircan MK, Şahin H, Korkmaz K (1996) Diagnosis of urethral strictures: Is retrograde urethrography still necessary? Int Urol Nephrol 28(6):801–804

Sun K, Huan Y, Unger PD (2008) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of urinary bladder and urethra: another urinary tract lesion immunoreactive for P504S. Arch Pathol Lab Med 132(9):1417–1422

Venyo AK-G (2015) Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Urethra: Review of the Literature. Int J Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/790235

Oliva E, Young RH (1996) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: a clinicopathologic analysis of 19 cases. Mod Pathol 9(5):513–520

Atay Gö UÇ, Baltaci S, Orhan D, Yaman Ö (2003) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the male urethra. Int J Urol 10:348–349

Sheahan G, Vega A (2018) Primary clear cell adenocarcinoma in a female urethral diverticulum: a case report and review. World J Nephrol Urol. Available at https://www.wjnu.org/index.php/wjnu/article/view/67. Accessed 2018.

Seseke F, Zöller G, Kunze E (2001) Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the male urethra in association with so-called nephrogenic metaplasia. Urol Int 67(1):104–108

Alexiev BA, Tavora F (2013) Histology and immunohistochemistry of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra: histogenesis and diagnostic problems. Virchows Arch 462(2):193–201

Gupta R, Gupta S, Basu S, Dey P, Khan IA (2017) Primary Adenocarcinoma of the Bulbomembranous Urethra in a 33-Year-Old Male Patient. J Clin Diagn Res. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/28918.10581

Cantrell BB, Leifer G, Deklerk DP, Eggleston JC (1981) Papillary adenocarcinoma of the prostatic urethra with clear-cell appearance. Cancer 48(12):2661–2667

Grosser D, Matoso A, Epstein J (2021) Clear cell adenocarcinoma in men: a Series of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 45(2):270–276

Hosseini J, Razi A, Javanmard B, Lotfi B, Mazloomfard MM (2011) Penile preservation for male urethral cancer. Iran J cancer Prev 4(4):199–201

Liu SV, Truskinovsky AM, Dudek AZ, Ramanathan RK (2012) Metastatic clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urethra in a male patient: report of a case. Clin Genitourin Cancer 10(1):47–49

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the patient, of blessed memory, and his family who remained supportive of his care and of this report.

Funding

No funding was required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SAA reviewed the write-up and directed the care of the patient; INC and MOI reviewed the literature, performed endoscopic and percutaneous procedures on the patient and provided the clinical and radiologic images; MOI performed the home visitation when the patient was otherwise moribund; AOT reviewed the write-up; AA and SO processed and stained the histologic specimen and provided photomicrographs; OBS reviewed the write-up. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not sought as it was not required for a case report. Informed consent was obtained from the patient. The patient consented to the report, including the use of clinical, radiologic and pathologic images. The signed consent form is available on request.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical information and images was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations'' (in PDF at the end of the article below the references; in XML as a back matter article note).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Adebayo, S.A., Chibuzo, I.N.C., Takure, A.O. et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the male urethra: a case report. Afr J Urol 28, 29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00296-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00296-5