Abstract

Background

Primary bladder neck obstruction (PBNO) is one of the causes of bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) and rarely results in renal failure. We are presenting the clinical characteristics of young male patients with PBNO and renal failure.

Methods

Medical records of patients between 18 and 40 years old with PBNO and renal failure were retrospectively reviewed (2014–2020). Patients with anatomical cause of BOO, and any urological or systemic disease or previous history of any surgical procedure associated with renal failure and/or lower urinary tract dysfunction were excluded. Serum creatinine measurement, ultrasonography, uroflowmetry, cystoscopy, and videourodynamics were performed.

Results

Seven male patients were identified, and the mean age of the patients was 28.8 years. Symptom duration was > 5 years in all patients. Two patients presented with difficult voiding, and five patients presented with both storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Three patients were previously misdiagnosed as overactive bladder. At presentation, serum creatinine levels were between 1.7 and 2.4 mg/dl. One patient was under hemodialysis treatment and waiting for renal transplantation. Mean detrusor pressure at maximum measured flow rate, mean maximum flow rate (Qmax), and mean average flow rate (Qave) was 67.6 cm H2O, 9.5 ml/s, and 5.5 ml/s, respectively. With α-blocker treatment, serum creatinine levels were stable or decreased after 12 months follow-up and mean Qmax and Qave were increased to 14.8 ml/s and 10.1 ml/s, respectively.

Conclusions

PBNO is a common disease in young men presenting with a long history of LUTS. Videourodynamics is mandatory for accurate diagnosis, but having a high clinical suspicion for PBNO is key to ensure the diagnosis. Clinicians should pay more attention to PBNO in young male patients with a long history of LUTS to prevent misdiagnosis, incorrect treatment, and possible decrease in renal function by years.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) can lead to renal failure, and the cause of obstruction varies among different age groups. Primary bladder neck obstruction (PBNO) is a urological condition affecting both sex in which the bladder neck fails to open adequately during voiding, resulting in obstruction of urinary flow in the absence of anatomic obstruction, such as benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) in men or genitourinary prolapse in women [1]. PBNO patients may present with a variety of symptoms including voiding lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), storage LUTS, and/or pelvic pain and discomfort [2]. In the current literature, the incidence of PBNO in female patients with obstructive symptoms and in male patients younger than 55 years of age with chronic voiding dysfunction is reported to be between 4.6–16% and 33–54%, respectively [2,3,4,5]. Although PBNO is a common urological problem, many young men with storage or voiding LUTS due to PBNO may be misdiagnosed and treated incorrectly [5]. In addition, PBNO rarely causes renal failure in otherwise healthy female and male patients [6]. The diagnosis of PNBO should be considered especially in young patients with a long history of LUTS. In this article, we present PBNO patients diagnosed while evaluating for renal failure.

2 Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (date: 14 July 2020, decision number: 2020-326) and followed the rules of Helsinki Declaration (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). Patient written informed consent was obtained.

Medical records of patients between 18 and 40 years old who presented to our nephrology and urology department with increased serum creatinine level (> 1.5 mg/dl; normal range 0.7–1.3 mg/dl) and PBNO were retrospectively reviewed between January 2014 and May 2020. Male patients older than 40 years old were excluded to rule out BPH. Patients with anatomical cause of BOO demonstrated by cystoscopy, voiding cystourethrography, and/or ultrasonography were excluded. Patients with a history of analgesic use, drug/alcohol abuse, urolithiasis, previous urological/pelvic surgery, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, neurological disease, drug intake, and any other systemic disease causing renal failure and/or lower urinary tract dysfunction were also excluded.

Patients were evaluated by serum creatinine, urine microscopy and culture, and urinary ultrasonography to assess renal function, BPH, bladder wall, urolithiasis, hydronephrosis, and renal paranchym. Uroflowmetry and post-void residual urine (PVR) measurement (with portable ultrasonography) was performed to evaluate maximum and average flow rates and residual urine. Videourodynamic (VUD) study was performed for patients with intermittent voiding pattern in uroflowmetry, low maximum flow rate (Qmax, < 15 ml/s), low average flow rate (Qave, < 10 ml/s), and high PVR (> 300 ml).

VUD study was performed with a filling rate of 50 ml/min of contrast solution through a 6-Fr dual lumen urethral catheter. Surface electromyography electrodes were placed to monitor the sphinteric activity. The storage phase and the voiding phase were performed in supine position. Simultaneous fluoroscopy images were recorded every 100 ml of bladder filling and during the voiding phase. If the patient did not feel bladder filling, the storage phase was terminated when the bladder volume was 550 ml and the voiding phase was initiated.

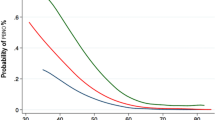

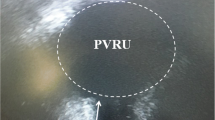

PBNO was defined as follows: low-flow (Qmax < 15 ml/s) and high-pressure voiding (detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate (PdetQmax) > 20 cm H2O, Fig. 1) with radiographic evidence of obstruction at the bladder neck (Fig. 2) and relaxation of the striated sphincter during VUD study and no evidence of distal obstruction on video cystourethrography and cystoscopy [7].

3 Results

Seven patients with PBNO and renal failure were identified. All patients were male, and the mean age of the patients was 28.8 years (range 20–39 years). Presenting symptom was difficult voiding in two patients and urgency, frequency, and difficult voiding in five patients. Symptom duration was > 5 years in all patients. Urinary incontinence was not reported. None of the patients reported urinary retention or catheterization history. Three patients were previously misdiagnosed as overactive bladder (OAB) in different urology departments and treated incorrectly with antimuscarinics. At presentation, serum creatinine levels were between 1.7 and 2.4 mg/dl. One patient was under hemodialysis treatment and waiting for renal transplantation. In this patient, bilateral vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and renal atrophy were identified. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Uroflowmetry, PVR measurement, and VUD study was performed to all patients. Normal detrusor function during storage phase and normal bladder compliance was demonstrated in all patients. High detrusor pressure during voiding phase was demonstrated in five patients (mean PdetQmax: 67.6 cm H2O). Two patients were unable to void during VUD study. Bladder neck was not opened adequately in five patients, and no proper funneling of the bladder neck was seen. Mean Qmax and mean Qave were 9.5 ml/s and 5.5 ml/s, respectively. In addition, PVR was < 200 ml in all patients (mean:130 ml) (Table 1).

α-blockers (silodosin 8 mg or alfuzosin 10 mg) were prescribed to six patients. Bladder neck incision was performed in one patient, who was waiting for renal transplantation. None of the patients needed self-catheterization. Symptom improvement was achieved, and serum creatinine levels were stable or decreased after 12-month follow-up. With α-blocker treatment, mean Qmax and mean Qave were increased to 14.8 ml/s and 10.1 ml/s, respectively. Also mean PVR was decreased to 110 ml.

4 Discussion

PBNO is one of the causes of BOO and may rarely result in renal failure [6]. The incidence of PBNO in men younger than 50 years with chronic voiding dysfunction was reported to be between 33 and 54% [3, 5]. On the other hand, literature data are limited about renal failure associated with PBNO. Although pathophysiology leading to obstructive uropathy in BPH is well known, PBNO remains a poorly understood and improperly diagnosed entity [6].

Obstructive uropathy has been identified to account for approximately 10% of all cases of renal failure [8]. Bladder diverticula or calculi, VUR, hydronephrosis, renal failure, and urinary retention appear with greater prevalence in patients with symptoms or signs of BPH [9]. Renal failure was identified in 13.6% of men presenting to a urologist for BPH treatment [10]. Hallan et al. showed that risk of renal failure in patients with LUTS secondary to BPH was found to be increasing with age [11]. Half of all men with chronic urinary retention have increased serum creatinine or upper urinary tract dilatation. Progressive upper tract dilatation and a decrease in glomerular filtration rate occur in patients with high-pressure chronic retention [10]. High intravesical pressure and low bladder compliance was found to be associated with renal failure [9, 12]. Urinary tract infection (UTI) also contributes to renal failure in patients with BPH [10]. On the other hand, no scientific proof exists that obstruction related to BPH or PVR triggers bacteriuria or UTI [9]. PBNO is probably sharing the same pathophysiological mechanisms with BPH, but further studies are needed to properly understand the exact mechanism underlying this clinical condition. All of our patients who were able to void during VUD study had high voiding pressure. Possibly, high voiding pressure caused renal failure in these patients.

PBNO patients may present with a variety of symptoms including voiding LUTS (slow urinary stream, intermittent stream, incomplete emptying), storage LUTS (frequency, urgency, urgency incontinence, nocturia), elevated PVR, urinary retention, and/or pelvic pain and discomfort [2, 6, 7, 13]. Nitti et al. reported that presenting symptoms were similar in men and women, with a combination of voiding and storage symptoms being common. In addition, pelvic pain was more common in men [7]. Similarly with these data, most of our patients were presented with both voiding and storage LUTS.

Renal failure due to PBNO is a rare condition. The largest series in the literature was presented by Kumar et al. [6]. The authors evaluated 13 patients (7 men and 6 women) with renal failure and PBNO. They reported that the most common presenting symptom was urinary retention in these patients and the mean serum creatinine at presentation was 7.0 mg/dl [6]. In our patients, the combination of voiding and storage symptoms was the most common presenting symptoms. None of our patients had a history of urinary retention, pelvic pain, or urinary incontinence, and serum creatinine at presentation was between 1.7 and 2.4 mg/dl. Only 1 of our patient was waiting for renal transplantation due to end-stage renal failure. Compared to patients reported by Kumar et al., our patients were in a better clinical condition.

The accurate and timely diagnosis of PBNO remains the primary challenge [14]. Given the variable symptom presentation and low incidence of the condition, having a high clinical suspicion for PBNO is key to ensure the diagnosis [2]. Although PBNO is a common disease in young men presenting with a long history of LUTS, many of these patients are misdiagnosed with chronic prostatitis, neurogenic bladder dysfunction, psychogenic voiding dysfunction, or pelvic pain [15]. Kaplan et al. reported that young men with chronic voiding symptoms were often misdiagnosed with prostatitis or prostatodynia and were treated empirically, with high failure rates [5]. Three of our patients were misdiagnosed with overactive bladder and were treated with antimuscarinics. Antimuscarinic treatment may worsen the symptoms of PBNO patients, since urinary retention is a well-known side effect of antimuscarinic treatment [16].

PBNO is a videourodynamic diagnosis, the hallmark of which is relative high-pressure, low-flow voiding with radiographic evidence of obstruction at the bladder neck with relaxation of the striated sphincter and no evidence of distal obstruction [7]. Detrusor contraction during voiding with a Pdet ≥ 20 cm water and Qmax ≤ 15 ml/s were found to be associated with the diagnosis of PBNO [3, 15]. Kumar et al. found that patients with renal failure and PNBO had high voiding pressure (mean 118.9 cm H2O) and low Qmax (mean 5.7 ml/s) at presentation [6]. In our study, we also found high detrusor pressure during voiding (mean 67.6 cm H2O) and low Qmax (mean 9.5 ml/s) in patients with PBNO and renal failure.

Treatment options for patients with PBNO include conservative management, alfa blockers, and bladder neck incision. Li et al. reported long-term results of doxazosin treatment in young male patients with PBNO and normal renal function. At 12-month follow-up, the success rate was found to be 66.8% [15]. Yang et al. reported significant improvement in flow rate and symptoms with doxazosin in young male patients with PBNO and normal renal function [3]. Successful results were achieved either with bladder neck incision. Trockman et al. performed bladder neck incision in young male patients with PBNO and normal renal function. The authors reported a mean 87% improvement in symptoms and significant improvements in Qmax and PVR [13]. Kumar et al. treated PBNO patients with renal failure [6]. They reported that clinical improvement was achieved with alfa blockers and bladder neck incision. Serum creatinine returned to near normal in 10 patients, but end-stage renal failure persisted in 2 patients [6]. We initiated silodosin or alfuzosin to six patients, and bladder neck incision was performed in one patient. Symptom improvement and increase in Qmax were achieved in all patients. Serum creatinine levels were stable or decreased after 6-month follow-up, except one patient with end-stage renal failure. We thought that conservative management is not appropriate for the patients with renal failure.

Retrospective design and low patients number are the main limitations of our study. Due to low patient number, we were not able to perform statistical analysis.

5 Conclusions

PBNO is a common disease in young men presenting with a long history of LUTS. PBNO rarely causes renal failure. The exact mechanism and prevalence of renal failure associated with PBNO are not known. Videourodynamics is mandatory for accurate diagnosis, but having a high clinical suspicion for PBNO is key to ensure the diagnosis. Treatment options include alfa blockers and bladder neck incision, but conservative management is not appropriate. To prevent misdiagnosis, incorrect treatment, and possible decrease in renal function by years, urologists should pay more attention to PBNO in young male patients with a long history of LUTS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BOO:

-

Bladder outlet obstruction

- BPH:

-

Benign prostatic hypertrophy

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- OAB:

-

Overactive bladder

- PBNO:

-

Primary bladder neck obstruction

- P detQmax :

-

Detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate

- PVR:

-

Post-void residual urine

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

- Q ave :

-

Average flow rate

- Q max :

-

Maximum flow rate

- VUD:

-

Videourodynamic

- VUR:

-

Vesicoureteral reflux

References

Camerota TC, Zago M, Pisu S, Ciprandi D, Sforza C (2016) Primary bladder neck obstruction may be determined by postural imbalances. Med Hypotheses 97:114–1116

Sussman RD, Drain A, Brucker BM (2019) Primary bladder neck obstruction. Rev Urol 21(2–3):53–62

Yang SS, Wang CC, Hsieh CH, Chen YT (2002) Alpha1-Adrenergic blockers in young men with primary bladder neck obstruction. J Urol 168(2):571–574

Nitti VW, Lefkowitz G, Ficazzola M, Dixon CM (2002) Lower urinary tract symptoms in young men: videourodynamics findings and correlation with noninvasive measures. J Urol 68(1):135–138

Kaplan SA, Ikeguchi EF, Santarosa RP, D’Alisera PM, Hendricks J, Te AE et al (1996) Etiology of voiding dysfunction in men less than 50 years of age. Urology 47(6):836–839

Kumar A, Banerjee GK, Goel MC, Mishra VK, Kapoor R, Bhandari M (1995) Functional bladder neck obstruction: a rare cause of renal failure. J Urol 154(1):186–189

Nitti VW (2005) Primary bladder neck obstruction in men and women. Rev Urol 7(8):12–17

Siddiqui MM, McDougal WS (2001) Urologic assessment of decreasing renal function. Med Clin N Am 95(1):161–168

Oelke M, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Thiruchelvam N, Heesakkers J (2012) Can we identify men who will have complications from benign prostatic obstruction (BPO)? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn 31(3):322–326

Rule AD, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ (2005) Is benign prostatic hyperplasia a risk factor for chronic renal failure? J Urol 173(3):691–696

Hallan SI, Kwong D, Vikse BE, Stevens P (2010) Use of a prostate symptom score to identify men at risk of future kidney failure: insights from the HUNT II Study. Am J Kidney Dis 56(3):477–485

Lu CH, Wu HHH, Lin TP, Huang YH, Chung HJ, Kuo JY et al (2019) Is intravesical prostatic protrusion a risk factor for hydronephrosis and renal insufficiency in benign prostate hyperplasia patients? J Chin Med Assoc 82(5):381–384

Trockman BA, Gerspach J, Dmochowski R, Haab F, Zimmern PE, Leach GE (1996) Primary bladder neck obstruction: urodynamic findings and treatment results in 36 men. J Urol 156(4):1418–1420

Brucker BM, Fong E, Shah S, Kelly C, Rosenblum N, Nitti VW (2012) Urodynamic differences between dysfunctional voiding and primary bladder neck obstruction in women. Urology 80(1):55–60

Li B, Gao W, Dong C, Han X, Li S, Jia R et al (2012) Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of α1-adrenergic blocker in young men with primary bladder neck obstruction: results from a single centre in China. Int Urol Nephrol 44(3):711–716

Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Muston D, Bitoun CE, Weinstein D (2008) The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 54(3):543–562

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AEC conducted retrospective data review, analyzed and interpreted the patient data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. BT, TE, MZ, MG read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

University of Health Sciences, Gulhane Faculty of Medicine, date: 14 July 2020, decision number: 2020–326. Written informed consent was obtained from patients.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Coguplugil, A.E., Topuz, B., Ebiloglu, T. et al. Primary bladder neck obstruction is one of the rare causes for renal failure in young adult males. Afr J Urol 27, 137 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-021-00243-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-021-00243-w