Abstract

Mitochondrial respiration complexes play a crucial function. As a result, dysfunction or change is intimately associated with many different diseases, among them cancer. The epigenetic, evolutionary, and metabolic effects of mitochondrial complex IΙ are the primary concerns of our review. Provides novel insight into the vital role of naringenin (NAR) as an intriguing flavonoid phytochemical in cancer treatment. NAR is a significant phytochemical that is a member of the flavanone group of polyphenols and is mostly present in citrus fruits, such as grapefruits, as well as other fruits and vegetables, like tomatoes and cherries, as well as foods produced from medicinal herbs. The evidence that is now available indicates that NAR, an herbal remedy, has significant pharmacological qualities and anti-cancer effects. Through a variety of mechanisms, including the induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, restriction of angiogenesis, and modulation of several signaling pathways, NAR prevents the growth of cancer. However, the hydrophobic and crystalline structure of NAR is primarily responsible for its instability, limited oral bioavailability, and water solubility. Furthermore, there is no targeting and a high rate of breakdown in an acidic environment. These shortcomings are barriers to its efficient medical application. Improvement targeting NAR to mitochondrial complex ΙΙ by loading it on chitosan nanoparticles is a promising strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a serious global public health issue. It is the second greatest cause of mortality, therefore advanced-stage disease and mortality rates may rise because of delayed diagnosis and treatment [74]. The American Cancer Society estimates the number of new cancer cases and deaths annually and compiles the most recent data on population-based cancer occurrence and outcomes. It is anticipated that there will be 609,820 cancer-related deaths and 1,958,310 new cancer cases in 2023 [55]. Recently cancer has been recognized as a metabolic disease. Cancer cells find many metabolic pathways to meet their needs. Among these OXPHOS plays a substantial role in the development of many cancer cells. OXPHOS supplies enough energy for the survival of tumor tissue while also regulating the conditions that promote tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [11, 41, 60].

Targeting tumor bioenergetics may be a promising approach to cancer therapy among the various new techniques, as it involves rewiring. The biochemical pathways linked to energy metabolism play a role in the development, persistence, and resistance of tumors to treatment. As a result, addressing mitochondrial metabolism, namely redox metabolism, is a promising therapeutic strategy. In this review, we discuss recent findings on modifications to the primary metabolic pathway that promotes cancer growth, such as endogenous succinate dehydrogenase SDH inhibitors that lead to succinate accumulation or dysregulation of (SDH). We additionally talk about the impact of succinate on angiogenesis, cell invasion, and migration, as well as how it triggers metabolic and epigenetic modifications that play a role in the development of cancer.

Respiratory chain and mitochondrial energy metabolism

Mitochondria are organelles well-known for their role in cellular respiration, particularly in linking the production of ATP and the reduction of molecular oxygen (O2). Numerous important metabolic pathways, including the urea cycle, oxidation, citric acid cycle (CAC), and heme synthesis, are housed in mitochondria [28]. The TCA cycle’s main role is to completely oxidize acetyl-CoA to CO2. Because it is necessary for the synthesis of the high-transfer-potential electron carriers flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH H+), it is recognized as the main process in energy metabolism [78]. The electron transport chain (ETC) is a network of electron carriers that allows high-energy electrons to go from NADH H+ and FADH2 to the terminal electron acceptor O2 as described in (Fig. 1). Mainly, the ETC does its function of establishing an electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane of the mitochondria (IMM), which is necessary for chemiosmotic ATP synthesis (OXPHOS) [20]. The respiratory chain complexes are among the largest membrane protein complexes in the cell. They transfer electrons from NADH and succinate to molecular oxygen via several redox cofactors including flavins, iron-sulfur clusters, hemes, and ions. The proton pumps are NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase or complex I, which oxidizes NADH, transfers two electrons to ubiquinone and translocates four protons across the membrane, ubiquinol: cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex III), which transfers electrons from ubiquinone to the peripheral electron carrier cytochrome c while translocating 4 protons, and cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), which transfers electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen and translocate two protons. In total 10 protons per NADH molecule are translocated across the IMM [12, 19].

The respiratory chain and mitochondrial energy metabolism. The end product of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism is acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA), which is oxidized to create CO2 by Krebs cycle processes. These reactions produce high-energy electrons (e−), which eventually enter the respiratory chain and decrease molecular oxygen (O2) to make water (H2O). This process releases energy, which is then used to create the electrochemical gradient that allows complex V to synthesize ATP by pumping protons (H+) across the inner membrane of the mitochondria [12]

Succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (succinate dehydrogenase (SDH))

SDH is a complex II mitochondrial enzyme that plays an active role in the electron transport chain within the mitochondria as well as the TCA cycle. SDH catalyzes the conversion of succinate to fumarate in the TCA cycle and carries electrons to the respiratory chain's ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) pool. The catalytic subunits in the hydrophilic head of SDH that extend into the mitochondrial matrix are subunits A (SDHA) and B (SDHB) [44]. These activities are carried out by the membrane-anchoring and ubiquinone-binding SDH subunits, SDHC, and SDHD, respectively as illustrated in (Fig. 2). The SDH assembly factor (SDHAF) is required for the flavination of SDHA, which is required for the formation of the SDH complex [67]. The 16 exons of the SDHA gene are located on chromosome 5p15.33 [10, 22]. The succinate binding site is a component of SDHA, which is the main catalytic element that converts succinate to fumarate. The SDHB gene, located on chromosome 1p35-36.1, consists of 8 exons [2, 80]. It facilitates electron transport to the ubiquinone pool and has three Fe-S centers. The location of the SDHC gene is 1q21, and it has 6 exons [36, 67], and the four exons of the SDHD gene are located on chromosome 11q23 [4, 52]. SDHC and SDHD bind to ubiquinone to generate protons, which subsequently convert to ATP [14].

The catalytic component SDH subunit A, which carries the flavin cofactor (FAD) to transfer electrons from succinate to the Fe-S center in the SDH subunit B subunit, then the electrons are subsequently transported to complex III by the ubiquinone pool that is integrated into the SDHC and SDHD subunits [43]

mRNA expression regulation

In addition to the SDH gene’s mutational status, other factors that affect SDH deficiency include methylation of the gene’s promoter and the expression of miRNAs. A full disassembly of the SDH complex and the ensuing lack of enzymatic activity is determined by the hypermethylation of the promoter of the SDHC subunit, which has been demonstrated to result in decreased mRNA expression of the subunit. Specifically, miRNAs -210, -31, and -378 are the three miRNAs that have been discovered to be overexpressed in cancer cells following radiation therapy. They target SDH mRNA. With significant effects on HIF1 activity and cell metabolism, miRNA-210 targets SDHD mRNA; miRNA-31 targets SDHA mRNA, which modifies ROS generation, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial mass; and miRNA-378 targets SDHB mRNA, which encourages cell proliferation and a metabolic shift away from oxidative metabolism as demonstrated in (Fig. 3) [16, 46].

Schematic representation of SDH expression and activity alterations: SDH mRNA targeting miRNAs [14]

Post-translation modification

Phosphorylation

SDH activity is governed at the post-translational stage by several methods, notably phosphorylation. For instance, the Y215 of the SDHA needs to be phosphorylated by c-Src kinase for the electron transfer of complex II to be successful [37, 50, 79]. It's also been found that in certain conditions like oxidative stress, SDHA phosphorylation is elevated, leading to improved respiration dependent on Complex II. Moreover, studies have shown that the dephosphorylation process, assisted by PTEN-like mitochondrial phosphatase-1 (PTPMT1), correlates to adjusting glucose levels and contributes to the disruption of SDH activity [15, 32, 40].

Deacetylase enzymes (SIRT3)

The acetylation of thirteen lysines in SDHA has been demonstrated, and the absence of SIRT3, a NAD-dependent deacetylase, has been shown to decrease the activity of the enzyme [68, 72, 82]. However, further research is required to understand the interaction between SDH and SIRT3 and how cells adapt to metabolic changes. SDH dysfunction, whether due to loss, reduction, or dysregulation, leads to altered metabolic traits through succinate accumulation [14, 33]. Naringenin, an AMPK-SIRT3 activator, has been found to protect against mitochondrial oxidative stress and maintain mitochondrial function during ischemia–reperfusion injury. Naringenin shows potential as a therapeutic option for mitochondrial dysfunction associated with various disorders [77, 82].

Role of TRAP1 on succinate dehydrogenase activity

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 (TRAP1) plays a vital role in different tumor types and is a significant member of the mitochondrial heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) family. TRAP1, also called Hsp75, is the mitochondrial counterpart of the molecular chaperone Hsp90 and exhibits a remarkable similarity in terms of amino acid sequence and domain structure. It is involved in various biological processes within the mitochondria [3, 21]. Members of the Hsp90 family are molecular chaperones that play a crucial role in the breakdown of proteins following aggregation, unfolding, or misfolding. These chaperones facilitate conformational modifications in proteins, enabling them to attain specific subcellular positions or form complex structures [38, 62]. The biochemical outcomes of these processes involve the integration of signaling and metabolic pathways, resulting in a comprehensive proteostasis that can be viewed as a dynamic mechanism for ensuring the quality control and efficiency of the proteome in response to varying environmental circumstances [21, 79]. TRAP1’s presence in the mitochondria makes it a suitable choice for regulating metabolic processes occurring within these organelles and responding to harmful conditions that affect mitochondrial function. Several studies have indicated that TRAP1 expression or activity tends to rise in response to pathological circumstances [73, 79].

Furthermore, alterations in TRAP1 have been detected in a situation of sudden onset inflammation, which was also correlated with an imbalance in cellular redox status [59]. In a pediatric patient diagnosed with Leigh syndrome, a mitochondrial disorder, there is an observed correlation with gastrointestinal dysmotility, chronic fatigue, and persistent discomfort. Additionally, a small subgroup of individuals with complex developmental syndromes, characterized by kidney malformations and abnormalities in other body regions, also exhibit this connection [9, 48, 56, 79]. Hence, it has been proposed that TRAP1 safeguards the mitochondria against damage in models of renal fibrosis [7], and a proband with thyroid and kidney malignancies was found to have a TRAP1 mutation [35]. Cancer model studies provide the main evidence suggesting that the chaperone may play a detrimental role. This is because TRAP1 is found to be significantly expressed in groups of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [31, 79]. Small cell lung cancer high-grade glioma, breast cancer [61], ovarian, kidney, prostate, esophageal, and colorectal cancer are diseases in which a connection has been established with advanced stage, metastasis, and an unfavorable prognosis [5]. The upregulation of TRAP1 occurs before the development of cancerous changes and is observed only in lesions that progress to carcinoma in colorectal cancer associated with ulcerative colitis and in a specific animal model of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progression. Although elevated TRAP1 levels are associated with a negative prognosis, strong TRAP1 expression is correlated with a higher chance of lymph node metastasis. However, the exact pathological significance of TRAP1 in cancer remains unclear [71]. These results indicate that TRAP1 plays an important part in the metabolic adaptations that facilitate the growth of tumors. As a result, researchers have conducted studies to gain a better understanding of its biochemical functions in different cancer scenarios. In recent years, there have been advancements in comprehending TRAP1’s structure, mechanism of action, interaction partners, and the effects it has on cellular functions. Additionally, the discovery of specific inhibitors has contributed to our understanding of TRAP1 as a key regulator in tumor energy metabolism.

A large amount of TRAP1 inhibits the respiratory complex II and leads to the generation of elevated levels of succinate, resulting in the reduction of SDH activity. Moreover, TRAP1 controls the opening of PTP in mitochondria by modulating the functions of OXPHOS complexes II and IV, which correspond to SDH and cytochrome c oxidase, respectively [30, 51]. The implications of the chaperon's capacity to transition between a dimer and a tetramer structure are currently unclear. Phosphorylation-induced activation of TRAP1 leads to downstream effects on Src tyrosine kinase and Ras/MEK/ERK signaling, enhancing its activity. Consequently, TRAP1-mediated inhibition of SDH causes an accumulation of succinate, which in turn triggers epigenetic changes, migration, and angiogenesis, as depicted in (Fig. 4). Additionally, TRAP1 promotes cellular invasion and migration through the STAT3/MMP2 pathway [29, 38, 71].

The biological process via which TRAP1 affects SDH. a The electron transport chain (ETC) complexes II and IV are bound by TRAP1 in the mitochondria, which stops them from functioning. TRAP1 is known to suppress cyclophilin D (CypD), which stops the permeability transition pore (PTP) from opening and the consequent activation of apoptosis by the release of cytochrome c. This is due to TRAP1's interaction with the protein deacetylase SIRT3. b Additionally, TRAP1 becomes more active when it is phosphorylated through a variety of pathways. Note that it is currently unclear if this happens before or after TRAP1 is imported into the mitochondria. c Because TRAP1 suppresses the ETC complex II, succinate accumulates as a result. This inhibits prolyl hydroxylases’ ability to stabilize HIF1 in the cytosol. Stabilized HIF1 and Myc initiate a pseudo-hypoxic program, which increases TRAP1 gene expression even more. d Inside mitochondria, TRAP1 interacts with ETC complexes I, III, and V (ATP synthase), but the implications of this interaction remain unknown. e TRAP1 dimers and tetramers coexist in the mitochondrial matrix, but it is yet unclear what influences the ratio of dimer to tetramer and whether or not they are functionally significant. f The carbon preference of mitochondria is influenced by TRAP1 levels. In TRAP1 KO cells, the carbon input into the TCA cycle derived from glucose and pyruvate is downregulated. A significant portion of glucose is diverted to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), where it is converted to ribose sugars and NADPH-reducing equivalents. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are increased in TRAP1 KO cells may be countered by this procedure. After decarboxylation, pyruvate typically enters the TCA cycle and aids in the creation of acetyl-CoA, an essential TCA cycle intermediate [23, 29]

Dysfunction of SDH

In the early 1920s, it was suggested that tumor cells could modify their glucose metabolism, resulting in a shift in their energy production towards glycolysis. This metabolic adaptation, commonly referred to as “aerobic glycolysis,” involves the generation of energy primarily through glycolytic pathways. While this hypothesis initially seems illogical, it has now been proven to be true [63]. The most efficient biological adaptation of cellular energy to facilitate rapid cancer cell growth was the reprogramming of the TCA cycle. This metabolic adjustment plays a crucial role in the development and progression of cancer through multiple stages [18, 63, 69, 81].

Epigenetic alteration

Consistent with topical investigations, succinate is a new “epigenetic hacker” that disrupts the process of DNA and histone demethylation [26]. Furthermore, succinylation is a post-translational alteration where a succinyl group is attached to a lysine residue through an amide bond. This alteration is believed to cause a significant change in the conformation of proteins, resulting in the masking of the positive charge on lysine. Various subcellular compartments, particularly mitochondria, undergo an overall increase in lysine succinylation due to the accumulation of succinate caused by the depletion of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). This succinate buildup ultimately leads to an epigenetic alteration in carcinomas [57]. Studies have confirmed the role of succinate in cellular transformation and cancer at both the biochemical and genomic levels [66, 76].

Neovascularization

Moreover, studies have shown that succinate induces cellular migration by activating the SUCNR1 receptor. This receptor also referred to as GPR91, is a member of the P2Y purinoreceptor family, which consists of G protein-coupled receptors [14]. Various tissues, such as blood cells, adipose tissue, the liver, retina, and kidney, exhibit the expression of this receptor. Recently, it has been discovered that this receptor, along with its ligand succinate, plays a crucial role in these tissues as a new regulator of local stress conditions like ischemia, hypoxia, toxicity, and hyperglycemia. Through the activation of PKC phosphorylation and subsequent activation of p38 MAPK, SUCNR1 induces cell migration as demonstrated in (Fig. 5) [39]. Furthermore, succinate triggers the formation of new blood vessels by activating extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) through the specific succinate receptor GPR91. This finding indicates that this process takes place independently of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) [8, 39]. A growing body of studies links the ERK1/2 signaling pathway to angiogenesis [45, 64, 75]. Furthermore, as stated by Loriot, Burnichon et al. [27], the accumulation of succinate leads to an excessive methylation process, which is capable of initiating the Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Furthermore, Wang et al. conducted a study revealing that the depletion of SDHB results in the activation of the TGFß signaling pathway within colorectal cancer cells. This activation occurs through the enhancement of the tight-junction transcriptional repression complex SNAIL1-SMAD3/SMAD4, ultimately leading to EMT, as well as promoting cell migration and invasion [34].

Diagram showing the signaling pathway that succinate uses to trigger cancer. The signaling mechanism that causes mitochondrial fission and succinate phosphorylation of Drp-1. ROS fuels the migration of cancer cells. Angiogenesis and metastasis are induced by extracellular regulated kinases (ERK1/2), phosphatidyl kinases (PI3K), and STAT3

Naringenin as SDH targeting therapy

Lately, there has been a growing interest in the use of natural compounds that can hinder tumor-specific alterations in mitochondrial metabolism. These substances have the potential to serve as an appealing therapeutic approach for triggering the activation of the cellular death process in cancer cells [25, 44, 49]. Flavonoids are commonly found in fruits, vegetables, and a variety of herbal preparations. They are prevalent polyphenols in the human diet. Numerous flavonoids have demonstrated antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [24].

In 1907, Power and Tutin discovered naringenin (NAR), a member of the flavanone group (2,3-dihydro-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one) [6]. NAR (C15 H12 O5) is a hydrophobic molecule with a molecular weight of 272.25 g/mol. It is mainly found as aglycones and is derived from the hydrolysis of naringin or narirutin. The primary sources of NAR include grapefruits, oranges, tomatoes, and lemons [1, 6]. Several studies have demonstrated the substantial pharmacological potential of NAR and its derivatives. These characteristics include cell cycle arrest, inactivation of carcinogens, and estrogen-like action. Furthermore, apoptosis is induced by p53 and members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, which are overexpressed and crucial in exerting pro-apoptotic effects in many malignancies (Fig. 6) [13, 65].

A Naringenin's mechanisms within the proliferation pathway. JAK: Janus kinase, a group of intracellular, non-receptor tyrosine kinases that use the JAK-STAT pathway to translate cytokine-mediated signals: transcription factors STAT, PI3K, AKT, protein kinase B, an important cell survival mediator, and mTOR, the mammalian target of rapamycin: NF-κB, also known as nuclear factor-kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, COX-2, or cyclooxygenase 2, and Notch, a vastly conserved cell signaling system utilized by most living things [58]. B Several routes are implicated in metabolic syndrome control by naringenin, as well as several mechanisms underlying metabolic illnesses [1]

Naringenin drawbacks

However, water solubility, low oral bioavailability, and instability of NAR are mostly caused by its hydrophobic and crystalline structure. Moreover, susceptibility to rapid degradation in an acidic environment, and no specific targeting. These drawbacks provide obstacles to its effective medicinal application [24].

Nanodrug-drug carrier as an emerging trend in medicine

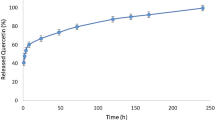

These physicochemical issues have been addressed by the development of drugs using nano-drug delivery techniques [13, 24, 47]. The surface modification of nanocarriers is primarily responsible for protecting the enclosed molecule from degradation and pH fluctuations, improving its ability to dissolve in liquids, and facilitating a controlled release of medication specifically to targeted cells. As a result, diverse types of nanocarriers have been created, including chitosan-based polymeric nanoparticles, owing to these influencing factors [54]. The progress in cancer treatment has specifically highlighted the utilization of biodegradable polymer nanoparticles such as chitosan (CS). CS consists of two subunits, D-glucosamine and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, which are connected by a (1,4) glycosidic bond [65, 70]. the amine group found on the glucosamine unit of CS is an essential part due to its potent and responsive positive charge. This positive charge enables CS to form complexes by combining with an anion molecule. Moreover, CS can enhance the transportation of medication through cell membranes [17, 42]. Chitosan nanoparticles containing naringenin were produced by ionically crosslinking CS (positive) and trisodium polyphosphate (TPP). The surface charge of NPs is typically one of the most significant elements affecting their stability throughout the short- and long term. Zeta potential indicated that the particles' surface charge had grown in our previous study. The increase in surface charge could be due to less TPP crosslinker neutralization of the NH3 groups. Particles with a high positive charge exhibit cohesiveness, tissue permeability, and greater stability. Chitosan nanoparticles have a positive zeta potential, which makes them more stable and capable of carrying medications since they can stick to negatively charged cell membranes more readily [42]. Owing to its unique sub-cellular size relative to the microscopic system, it is expected that the formulation of CS with NAR will result in substantial intracellular absorption [70]. As a result, the anti-cancer potential of the starting molecule, in this case NAR, can be enhanced.

Our previous studies suggest that CS capsulate flavonoid drugs make it targeted to specific sites on SDH especially at the UbQ-binding site between the SDHC and SDHD subunits in recent research, which demonstrated that they greatly inhibited SDH activity in cancer cells [42, 44, 49, 53].

Conclusion

Cellular energy metabolism is the hallmark of almost all malignancies. Unlike healthy cells, which mostly obtain their useful energy from oxidative phosphorylation, most cancerous cells rely significantly on substrate-level phosphorylation to fulfill their energy requirements. succinate buildup caused by an imbalance in SDH activity, control, or mitochondrial chaperones. Due to its effects on angiogenesis, invasion, and cell migration, as well as the generation of epigenetic and metabolic alterations, succinate is a major factor in the development of cancer. Thus, strategies that prevent succinate from piling up are required. Flavonoids have recently been a key player in the control of SDH activity. Among these is NAR, an ingredient found naturally in a wide variety of fruits. According to scientific research, there appears to be little chance of major adverse effects developing, and compared to other chemotherapy medications, it should have a safer profile. However, given the outcomes of in vitro and in vivo models thus far, additional research is needed to understand the bioavailability and release of novel formulations for encapsulating NAR, such as chitosan nanoparticles, concerning clinical studies. Thus, naringenin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles are paving the way for the creation of novel metabolic cancer treatments.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- OXPHOS:

-

Oxidative phosphorylation dysregulation

- SIRT3:

-

Sirtuin 3

- SDH:

-

Succinate dehydrogenase

- NAR:

-

Naringenin

- SDHA:

-

Subunit A

- SDHB:

-

Subunit B

- SDHC:

-

Subunit C

- SDHD:

-

Subunit D

- SDHAF:

-

SDH assembly factor

- TRAP1:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CypD:

-

Cyclophilin D

- PTP:

-

Permeability transition pore

- ETC:

-

Electron transport chain

- PPP:

-

Pentose phosphate pathway

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- PTPMT1:

-

PTEN-like mitochondrial phosphatase-1

- ERK:

-

Extracellular regulated kinase

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- JAK:

-

Janus kinase

- COX-2:

-

Cyclooxygenase 2

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor-kappa-light-chain

- CS:

-

Chitosan

- TPP:

-

Tri-sodium polyphosphate

References

Arafah A, Rehman MU, Mir TM, Wali AF, Ali R, Qamar W, Khan R, Ahmad A, Aga SS, Alqahtani S. Multi-therapeutic potential of naringenin (4′, 5, 7-trihydroxyflavonone): experimental evidence and mechanisms. Plants. 2020;9:1784.

Astuti D, Latif F, Dallol A, Dahia PL, Douglas F, George E, Sköldberg F, Husebye ES, Eng C, Maher ER. Gene mutations in the succinate dehydrogenase subunit SDHB cause susceptibility to familial pheochromocytoma and to familial paraganglioma. Am J Human Genet. 2001;69:49–54.

Avolio R, Agliarulo I, Criscuolo D, Sarnataro D, Auriemma M, de Lella S, Pennacchio S, Calice G, Ng MY, Giorgi C. Cytosolic and mitochondrial translation elongation are coordinated through the molecular chaperone TRAP1 for the synthesis and import of mitochondrial proteins. Genome Res. 2023;33:1242–57.

Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Myssiorek D, Bosch A, Mey AVD, Taschner PE, Rubinstein WS, Myers EN. Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science. 2000;287:848–51.

Bhasin N, Dabral P, Senavirathna L, Pan S, Chen R. Inhibition of TRAP1 Accelerates the DNA damage response, activation of the heat shock response and metabolic reprogramming in colon cancer cells. Front Biosci-Landmark. 2023;28:227.

Bhia M, Motallebi M, Abadi B, Zarepour A, Pereira-Silva M, Saremnejad F, Santos AC, Zarrabi A, Melero A, Jafari SM. Naringenin nano-delivery systems and their therapeutic applications. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:291.

Bhreathnach U, Griffin B, Brennan E, Ewart L, Higgins D, Murphy M. Profibrotic IHG-1 complexes with renal disease associated HSPA5 and TRAP1 in mitochondria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:896–906.

Bobkov YV, Walker WB III, Cattaneo AM. Altered functional properties of the codling moth Orco mutagenized in the intracellular loop-3. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3893.

Boles RG, Hornung HA, Moody AE, Ortiz TB, Wong SA, Eggington JM, Stanley CM, Gao M, Zhou H, McLaughlin S. Hurt, tired and queasy: specific variants in the ATPase domain of the TRAP1 mitochondrial chaperone are associated with common, chronic “functional” symptomatology including pain, fatigue and gastrointestinal dysmotility. Mitochondrion. 2015;23:64–70.

Casas-Benito A, Martínez-Herrero S, Martínez A. Succinate-directed approaches for Warburg effect-targeted cancer management, an alternative to current treatments? Cancers. 2023;15:2862.

Clemente-Suárez VJ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Redondo-Flórez L, Ruisoto P, Navarro-Jiménez E, Ramos-Campo DJ, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Metabolic health, mitochondrial fitness, physical activity, and cancer. Cancers. 2023;15:814.

Cogliati S, Cabrera-Alarcón JL, Enriquez JA. Regulation and functional role of the electron transport chain supercomplexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2021;49:2655–68.

Dadwal V, Gupta M. Recent developments in citrus bioflavonoid encapsulation to reinforce controlled antioxidant delivery and generate therapeutic uses. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63:1187–207.

Dalla Pozza E, Dando I, Pacchiana R, Liboi E, Scupoli MT, Donadelli M, Palmieri M. Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase and role of succinate in cancer. Sem Cell Dev Biol. 2020;98:4–14. Academic Press.

Dikal MV. Determination of the activity of nadh dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase and H+-ATP-ASE in experimental diabetes. (Doctoral dissertation, Буковинський державний медичний університет). 2023:68–9.

Eijkelenkamp K, Osinga TE, Links TP, Van der Horst-Schrivers AN. Clinical implications of the oncometabolite succinate in SDHx-mutation carriers. Clin Genet. 2020;97:39–53.

Fitriyani A, Winarti L, Muslichah S, Nuri N. Anti-inflammatory activity of Piper crocatum Ruiz & Pav. leaves metanolic extract in rats. Majalah Obat Tradisional. 2011;16:34–42.

Fliedner SM, Kaludercic N, Jiang X-S, Hansikova H, Hajkova Z, Sladkova J, Limpuangthip A, Backlund PS, Wesley R, Martiniova L. Warburg effect’s manifestation in aggressive pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: insights from a mouse cell model applied to human tumor tissue. 2012.

Greene J, Segaran A, Lord S. Targeting OXPHOS and the electron transport chain in cancer; Molecular and therapeutic implications. Sem Cancer Biol. 2022;86:851–9. Academic Press.

Gu L. Optimizing the electron transport chain to sustainably improve photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2023;193:2398–412.

Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–32.

Her YF, Maher LJ. Succinate dehydrogenase loss in familial paraganglioma: biochemistry, genetics, and epigenetics. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:1–14.

Joshi A, Ito T, Picard D, Neckers L. The mitochondrial HSP90 paralog TRAP1: structural dynamics, interactome, role in metabolic regulation, and inhibitors. Biomolecules. 2022;12:880.

Kahrizi D, Mohammadi MR, Amini S. Micro and nano formulas of phyto-drugs naringenin and naringin with antineoplastic activity: Cellular and molecular aspects. Micro Nano Bio Aspects. 2023;2:27–33.

Khoo BY, Chua SL, Balaram P. Apoptotic effects of chrysin in human cancer cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:2188–99.

Liu C, Liu Y, Chen L, Zhang M, Li W, Cheng H, Zhang B. Quantitative proteome and lysine succinylome analyses provide insights into metabolic regulation in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2019;26:93–105.

Loriot C, Burnichon N, Gadessaud N, Vescovo L, Amar L, Libe R, Bertherat J, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Favier J. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is activated in metastatic pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas caused by SDHB gene mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;1;97(6):E954–62.

Liu YE, Chen C, Wang X, Sun Y, Zhang J, Chen J, Shi Y. An epigenetic role of mitochondria in cancer. Cells. 2022;11:2518.

Masgras I, Laquatra C, Cannino G, Serapian SA, Colombo G, Rasola A. The molecular chaperone TRAP1 in cancer: From the basics of biology to pharmacological targeting. Sem Cancer Biol. 2021;76:45–53. Academic Press.

Matassa DS, Agliarulo I, Avolio R, Landriscina M, Esposito F. TRAP1 regulation of cancer metabolism: dual role as oncogene or tumor suppressor. Genes. 2018;9:195.

Megger DA, Bracht T, Kohl M, Ahrens M, Naboulsi W, Weber F, Hoffmann A-C, Stephan C, Kuhlmann K, Eisenacher M. Proteomic differences between hepatocellular carcinoma and nontumorous liver tissue investigated by a combined gel-based and label-free quantitative proteomics study. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2006–20.

Moosavi B, Zhu X-L, Yang W-C, Yang G-F. Genetic, epigenetic and biochemical regulation of succinate dehydrogenase function. Biol Chem. 2020;401:319–30.

Neeli PK, Gollavilli PN, Mallappa S, Hari SG, Kotamraju S. A novel metadherinΔ7 splice variant enhances triple negative breast cancer aggressiveness by modulating mitochondrial function via NFĸB-SIRT3 axis. Oncogene. 2020;39:2088–102.

Neeli PK, Sahoo S, Karnewar S, Singuru G, Pulipaka S, Annamaneni S, Kotamraju S. DOT1L regulates MTDH-mediated angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancer: intermediacy of NF-κB-HIF1α axis. FEBS J. 2023;290:502–20.

Nicolas E, Demidova EV, Iqbal W, Serebriiskii IG, Vlasenkova R, Ghatalia P, Zhou Y, Rainey K, Forman AF, Dunbrack Jr RL, Golemis EA. Interaction of germline variants in a family with a history of early‐onset clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(3):e556.

Niemann S, Müller U. Mutations in SDHC cause autosomal dominant paraganglioma, type 3. Nat Genet. 2000;26:268–70.

Ogura M, Yamaki J, Homma MK, Homma Y. Mitochondrial c-Src regulates cell survival through phosphorylation of respiratory chain components. Biochem J. 2012;447:281–9.

Ou Y, Liu L, Xue L, Zhou W, Zhao Z, Xu B, Song Y, Zhan Q. TRAP1 shows clinical significance and promotes cellular migration and invasion through STAT3/MMP2 pathway in human esophageal squamous cell cancer. J Genet Genomics. 2014;41:529–37.

Park SY, Le CT, Sung KY, Choi DH, Cho E-H. Succinate induces hepatic fibrogenesis by promoting activation, proliferation, and migration, and inhibiting apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:673–8.

Perry JJP, Ballard GD, Albert AE, Dobrolecki LE, Malkas LH, Hoelz DJ. Human C6orf211 encodes Armt1, a protein carboxyl methyltransferase that targets PCNA and is linked to the DNA damage response. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1288–96.

Qiu X, Li Y, Zhang Z. Crosstalk between oxidative phosphorylation and immune escape in cancer: a new concept of therapeutic targets selection. Cell Oncol. 2023;46(4):847–65.

Ragab EM, el Gamal DM, Mohamed TM, Khamis AA. Study of the inhibitory effects of chrysin and its nanoparticles on mitochondrial complex II subunit activities in normal mouse liver and human fibroblasts. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2022;20:1–15.

Ragab EM, el Gamal DM, Mohamed TM, Khamis AA. Therapeutic potential of chrysin nanoparticle-mediation inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase and ubiquinone oxidoreductase in pancreatic and lung adenocarcinoma. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27:172.

Ragab EM, el Gamal DM, Mohamed TM, Khamis AA. Impairment of electron transport chain and induction of apoptosis by chrysin nanoparticles targeting succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase in pancreatic and lung cancer cells. Genes Nutr. 2023;18:1–15.

Rapizzi E, Ercolino T, Fucci R, Zampetti B, Felici R, Guasti D, Morandi A, Giannoni E, Giaché V, Bani D. Succinate dehydrogenase subunit B mutations modify human neuroblastoma cell metabolism and proliferation. Hormones Cancer. 2014;5:174–84.

Richter S, Garrett TJ, Bechmann N, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Ghayee HK. Metabolomics in paraganglioma: applications and perspectives from genetics to therapy. Endocrine-related Cancer. 2023;30(6):1–16.

Rudrapal M, Mishra AK, Rani L, Sarwa KK, Zothantluanga JH, Khan J, Kamal M, Palai S, Bendale AR, Talele SG. Nanodelivery of dietary polyphenols for therapeutic applications. Molecules. 2022;27:8706.

Saisawat P, Kohl S, Hilger AC, Hwang D-Y, Gee HY, Dworschak GC, Tasic V, Pennimpede T, Natarajan S, Sperry E. Whole-exome resequencing reveals recessive mutations in TRAP1 in individuals with CAKUT and VACTERL association. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1310–7.

Salimi A, Roudkenar MH, Seydi E, Sadeghi L, Mohseni A, Pirahmadi N, Pourahmad J. Chrysin as an anti-cancer agent exerts selective toxicity by directly inhibiting mitochondrial complex II and V in CLL B-lymphocytes. Cancer Invest. 2017;35:174–86.

Salvi M, Morrice NA, Brunati AM, Toninello A. Identification of the flavoprotein of succinate dehydrogenase and aconitase as in vitro mitochondrial substrates of Fgr tyrosine kinase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5579–85.

Sarkar S, Halder B. The role of TRAP1, the mitochondrial Hsp90 in cancer progression and as a possible therapeutic target. Curr Sci. 2023;00113891:124.

Schipani A, Nannini M, Astolfi A, Pantaleo MA. SDHA germline mutations in SDH-deficient GISTs: a current update. Genes. 2023;14:646.

Seydi E, Rahimpour Z, Salimi A, Pourahmad J. Selective toxicity of chrysin on mitochondria isolated from liver of a HCC rat model. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27:115163.

Sharma S, Hafeez A, Usmani SA. Nanoformulation approaches of naringenin-an updated review on leveraging pharmaceutical and preclinical attributes from the bioactive. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2022;76:103724.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48.

Skinner SJ, Doonanco KR, Boles RG, Chan AK. Homozygous TRAP1 sequence variant in a child with Leigh syndrome and normal kidneys. Kidney Int. 2014;86:860.

Smestad J, Erber L, Chen Y, Maher LJ. Chromatin succinylation correlates with active gene expression and is perturbed by defective TCA cycle metabolism. Iscience. 2018;2:63–75.

Stabrauskiene J, Kopustinskiene DM, Lazauskas R, Bernatoniene J. Naringin and naringenin: their mechanisms of action and the potential anticancer activities. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1686.

Standing AS, Hong Y, Paisan-Ruiz C, Omoyinmi E, Medlar A, Stanescu H, Kleta R, Rowcenzio D, Hawkins P, Lachmann H, McDermott MF. TRAP1 chaperone protein mutations and autoinflammation. Life Sci Alliance. 2020;3(2):1–12.

Sun Y, Guo Y, Shi X, Chen X, Feng W, Wu L-L, Zhang J, Yu S, Wang Y, Shi Y. An overview: the diversified role of mitochondria in cancer metabolism. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:897.

Tan L-M, Ke S-P, Li X, Ouyang T-L, Yu L-Q, Yu J-L, Wang Y-K, Yang Q-J, Li X-H, Yu X. The value of serum TRAP1 in diagnosing small cell lung cancer and tumor immunity. Exp Biol Med. 2023;248:201–8.

Tedesco B, Vendredy L, Timmerman V, Poletti A. The chaperone-assisted selective autophagy complex dynamics and dysfunctions. Autophagy. 2023;19(6):1619–41.

van der Horst-Schrivers AN. Clinical implications of the oncometabolite succinate in SDHx-mutation carriers. 2019

Vickers NJ. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr Biol. 2017;27:R713–5.

Vieira IR, Conte-Junior CA. Nano-delivery systems for food bioactive compounds in cancer: Prevention, therapy, and clinical applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64(2):381–406.

Vikramdeo KS, Sharma A, Anand S, Sudan SK, Singh S, Singh AP, Dasgupta S. Mitochondrial alterations in prostate cancer: roles in pathobiology and racial disparities. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:4482.

Wang Q, Li M, Zeng N, Zhou Y, Yan J. Succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit C: role in cellular physiology and disease. Exp Biol Med. 2023;248:263–70.

Wang X, Nan N, Fu X, Zeng R, Yang Y, Xuan S, Shi J-S, Wu Q, Zhou S. Activation of SIRT3 alleviates neurodegeneration via rescuing mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase activity and bioenergy supply in rotenone-induced PD models. 2022. Authorea Preprints.

Wang Y, Patti GJ. The Warburg effect: a signature of mitochondrial overload. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33(12):1014–20.

Winarti L, Sari LORK, Nugroho AE. Naringenin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles formulation, and its in vitro evaluation against t47d breast cancer cell line. 2015.

Xiang Y, Liu X, Sun Q, Liao K, Liu X, Zhao Z, Feng L, Liu Y, Wang B. The development of cancers research based on mitochondrial heat shock protein 90. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1296456.

Xiao X, Wu Z-C, Chou K-C. A multi-label classifier for predicting the subcellular localization of gram-negative bacterial proteins with both single and multiple sites. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20592.

Xu L, Voloboueva LA, Ouyang Y, Giffard RG. Overexpression of mitochondrial Hsp70/Hsp75 in rat brain protects mitochondria, reduces oxidative stress, and protects from focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:365–74.

Yabroff KR, Wu X-C, Negoita S, Stevens J, Coyle L, Zhao J, Mumphrey BJ, Jemal A, Ward KC. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with patterns of statewide cancer services. JNCI: J National Cancer Institute. 2022;114:907–9.

Yang L, Zhao Y, Yi P, Lu L, Yao D, Lu Y. TRAP1 controls the crosstalk between SDHA/HIF-1α, HIF/ERK1/2/Twist, and HIF/FoxC/Twist pathways via HIF-1α during EMT in colorectal cancer. 2023.

Yang M, Soga T, Pollard PJ. Oncometabolites: linking altered metabolism with cancer. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:3652–8.

Yu L-M, Dong X, Xue X-D, Zhang J, Li Z, Wu H-J, Yang Z-L, Yang Y, Wang H-S. Naringenin improves mitochondrial function and reduces cardiac damage following ischemia-reperfusion injury: the role of the AMPK-SIRT3 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2019;10:2752–65.

Zhang W, Roy S, Assadpour E, Cong X, Jafari SM. Cross-linked biopolymeric films by citric acid for food packaging and preservation. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;314:102886.

Zhao Y, Yi P, Lu L, Du Y. Implications of TRAP1 modulate cell invasion and epithelial–mesenchymal transition in liver cancer: evidence from in vitro HepG2 study. 2023.

Zheng J, Liu S, Wang D, Li L, Sarsaiya S, Zhou H, Cai H. Unraveling the functional consequences of a novel germline missense mutation (R38C) in the yeast model of succinate dehydrogenase subunit B: insights into neurodegenerative disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1246842.

Zhong X, He X, Wang Y, Hu Z, Huang H, Zhao S, Wei P, Li D. Warburg effect in colorectal cancer: The emerging roles in tumor microenvironment and therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:160.

Zhou Q, Wang Y, Lu Z, Wang B, Li L, You M, Wang L, Cao T, Zhao Y, Li Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by SIRT3 inhibition drives proinflammatory macrophage polarization in obesity. Obesity. 2023;31:1050–63.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Biochemistry department, Faculty of Science Tanta University, Egypt.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RE: writing original draft preparation, designing all figures, and editing. GD: conceptualization. MT: supervision and investigation. KA: reviewing and editing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ragab, E.M., Khamis, A.A., Gamal, D.M.E. et al. Comprehensive overview of how to fade into succinate dehydrogenase dysregulation in cancer cells by naringenin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. Genes Nutr 19, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-024-00740-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-024-00740-x