Abstract

Background

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) reduces stroke and mortality risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF). Patterns of OAC initiation upon discharge from US emergency departments (ED) are poorly understood. We sought to examine stroke prophylaxis actions upon, and shortly following, ED discharge of stroke-prone AF patients.

Methods

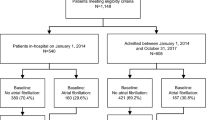

We included all adults with a primary diagnosis of non-valvular AF, high stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2), low/intermediate bleeding risk (HAS-BLED < 4), and no recent (< 90 days) OAC at discharge from 21 community EDs (2010–2017). Annual rates of appropriate stroke prevention action (OAC Action) were calculated for eligible discharges and as defined as an OAC prescription or anticoagulation management service consultation within 14 days of ED discharge. We modeled OAC Action using a parsimonious Poisson regression with identity link adjusting for sex, age, race/ethnicity, stroke risk score (CHA2DS2-VASc), year of visit, provider race/ethnicity, number of ED beds, and presence of an outpatient observation unit, with the patient as a random effect.

Results

We studied 9,603 eligible ED discharges (mean age 73.1 ± 11.4 years, 62.3% female), and mean CHA2DS2-VASc score 3.5 ± 1.5. From 2010 to 2017, OAC Action increased from 21.0% to 33.5%. Factors associated with lower OAC initiation included the following: female sex (-3.6%, 95% CI -5.4 to -1.9), age ≥ 85 vs < 64 years (-3.8%, 95% CI -6.7 to -1.0%), ED beds, n = 20 to 29 (-5.3%, 95% CI -8.36 to -2.4%), 30–49 (-3.8, 95% CI -6.5 to -1.2%), and 50 + (-7.1%, 95% CI -10.6 to -3.7%); with referent being the male sex, < 40 years, and fewer than 20 beds (18.1%, 95% CI 12.8 to 23.4). OAC initiation in 2017 was greater than in 2010 (16.0%, 95% CI 12.3 to 19.7%).

Conclusion

Within a community-based ED population of AF patients at high stroke risk, rates of appropriate stroke prevention action increased over the 7-year study period. Rates of AF thromboprophylaxis may be improved by addressing sex and age disparities, as females and those age ≥ 75 were less likely to receive indicated stroke prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atrial fibrillation and flutter (hereafter denoted as AF for brevity) is a common arrhythmia with significant morbidity and mortality, and increases the lifetime risk of stroke more than five-fold compared with a non-AF reference population [1, 2]. Findings from large prospective randomized controlled clinical trials demonstrate that oral anticoagulation (OAC) reduces the risk of AF-associated thromboembolic events [2,3,4,5,6]. The importance of timely OAC prescription in appropriate patients is recommended in guidelines globally [2, 7,8,9]. However, among those at highest risk based on guidelines, “real-life” data show that up to two-thirds of eligible AF outpatients at risk for thromboembolic events are not prescribed OAC as indicated [9,10,11]. Additionally, prior studies have indicated that physician characteristics, such as race, if concordant with the patient, can impact guideline adherence [12,13,14]. Furthermore, a Medicare study of emergency department (ED) patients found that less than 20% of patients with new-onset AF who were eligible for stroke prophylaxis were prescribed an OAC, regardless of stroke risk [15].

With more than a half-million patients with acute AF presenting to U.S. EDs per year, and over 25% of all new AF diagnoses made in the ED, the trajectory of AF care often begins in the ED [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. With the increased availability of direct OACs (DOACs) and the ease of management associated with their use, the ED is an overlooked opportunity to improve that trajectory of care. Understanding OAC prescriber characteristics, prescribing practices, and time delays to appropriate care in an integrated system, where follow-up is readily available, could help identify opportunities to improve prescribing practices from the ED.

Thus, we sought to examine stroke prophylaxis actions upon and shortly following ED discharge of stroke-prone AF patients and to identify factors associated with delays in prescribing OAC following an ED visit. This retrospective study lays the groundwork for identifying longer-term outcomes (namely stroke and bleeding risk) and whether stroke risk stratification scores apply to the ED patient population.

Methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all adult health plan members with continuous prescription benefits and a primary diagnosis of non-valvular AF who were OAC-naive on ED arrival.

Study setting

The study included 21 community medical centers in Northern California over an 8-year period (January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2017). Northern California geographically comprises the state’s northernmost 48 counties (socioeconomic characteristics available in Appendix 1). Each site had cardiology available around the clock for consultation, outpatient pharmacy, and anticoagulation management service (AMS). AMS is a pharmacist-led, phone-based service that provides patient education and close monitoring of patients on warfarin and DOACs (Appendix 1). They also serve as consultants for clinicians.

Study population

To select patients not on OACs, we excluded patients with a prior OAC fill three months prior to the index visit and those with an OAC on their current medication list. Only patients discharged home from the ED were included. We included AF patients with indications for stroke prophylaxis with high CHA2DS2-VASc scores ≥ 2 and low/intermediate bleeding risk by HAS-BLED (score < 4), as an OAC prescription for this cohort would follow American Heart Association guidelines and minimize the risk of bleeding events for the risk-averse ED clinician [23]. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was stroke prevention action (OAC Action) within 14 days of the index ED visit. An OAC Action was defined a priori as an OAC prescription or AMS consultation (i) by an ED clinician at the time of discharge or (ii) by any clinician within 14 days following ED discharge. We used the filling of the prescription as a proxy for prescribing. OACs prescribed and filled with prescription drug coverage included warfarin, a DOAC (dabigatran was placed on the system’s formulary starting in 2014, followed by apixaban in 2016), warfarin and enoxaparin bridge, and others (i.e., dalteparin, fondaparinux, or enoxaparin only).

Variables

For our cohort, we identified patient demographics (sex, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity) and stroke risk stratification scores by (1) CHA2DS2-VASc: congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, prior stroke (including ischemic versus hemorrhagic), vascular disease, and sex, and (2) bleeding risk (defined by HAS-BLED score); and by year of index encounter [24,25,26,27,28]. Additionally, physician characteristics (sex, years in practice as a proxy for experience, race/ethnicity, language, and race concordance with the patient—as self-documented by the physician and patient) and hospital characteristics (number of ED beds and annual ED census, and availability of an outpatient observation unit) were also analyzed. Detailed information of data abstraction method is described in Appendix 2.

Statistical analysis

We generated descriptive statistics and bivariate analyses to characterize the sample and to identify candidate predictors of OAC Action. When comparing categorical measures, we used chi-square tests. For continuous independent variables, we used t-tests and the pooled or Satterthwaite method to determine differences in means between those with and those without appropriate OAC Action. Annual rates of OAC initiation were calculated for eligible discharges.

We used a hierarchical, multivariable risk-adjustment model to evaluate patient, physician, and hospital factors associated with OAC Action. On the patient level, we used multivariable logistic regression to determine the influence of stroke risk classification, CHA2DS2-VASc, on OAC Action, and the influence of other patient, physician, and hospital factors. We used a generalized estimating equation design with a Poisson distribution, identity link, and an independent correlation structure to account for clustering by physician and hospital, as well as repeated measures by a patient via an alternating logistic regression model that allowed for three-level clustering. This generated population-level rates of OAC Action within 14 days. Database management and all analyses were conducted using SAS (v 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

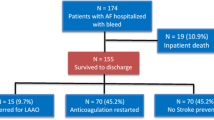

Of the 319,961 adult health plan members with at least one ED diagnosis of AF during 2010–2017, 9603 met our eligibility criteria and formed the primary sample for analysis (Fig. 1). The majority of patients (such as those with transient secondary AF) were excluded as AF was not the primary diagnosis, or the patient had gaps in insurance coverage or evidence of current or recent OAC use. Transient secondary AF is new onset of AF occurring secondary to any acute medical condition (ie. peri-procedural, hyperthyroidism, alcohol intoxication, or infection), and typically self-resolves.

The mean age of our cohort was 73.1 ± 11.4 years, of whom 5986 (62.3%) were female, and 7322 (76.3%) were non-Hispanic white. We compared characteristics between those patients who had any OAC Action within 14 days of diagnosis (N = 2577, 26.8%) versus those without OAC Action (N = 7026, 73.2%; Table 1). The mean ages, stroke risk, and bleeding risk scores, were similar between the two groups.

The following patient groups received increased Action compared with others within their category: males more than females, 29.0% vs 25.5% (p < 0.001), ages 75–84 years (n = 871, 32.7%), Asian (n = 200, 30.8%), and CHA2DS2-VASc score 4–5 (n = 953, 30.3%).

Physician and hospital characteristics were also compared. There were more male than female physicians (67.5% vs 32.4%), but they had similar OAC Action. Physicians had similar mean years of experience: 14.8 ± 8.5 years. Language concordance and discordance between physicians and patients for OAC Action were similar. There was a higher proportion of OAC Action among discordant physician–patient race/ethnicity than concordance (29.9% vs 26.7%).

In Table 2, the rate of OAC Action increased over time, from 21.0% in 2010 to 43.6% in 2017 (hospital-level data available in Appendix 3). Breaking down OAC Action, we found that the overall rate of ED prescribing remained low, 2.4% in 2010 to 6.0% in 2017 (Fig. 2).

After adjusting for patient demographic and clinical variables, patient and physician race/ethnicity and language concordance, clinical years of experience, and hospital-related characteristics were no longer significant as they were in the univariate model. In our parsimonious model (Table 3), females and older patients (> 85 years old) were approximately 4% less likely to receive an OAC Action compared with males and those less than 64 years of age. Patients of Hispanic White ethnicity had higher rates of OAC Action (5.5% higher, all other factors being equal); Black/African American and Asian differences, while still higher than referent non-Hispanic Whites, were non-significant or borderline significant. Patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc risk score of 4–5 were prescribed anticoagulants at rates 4.5% higher than a risk score of 2–3; and there was no difference in the highest risk CHA2DS2-VASc category (risk score of 6–9) compared with the lowest category in this cohort (risk score of 2–3). Asian physicians acted at 4.5% higher rates than other physician races/ethnicities (Table 3).

Discussion

In this 21-center study of ED patients with low/intermediate bleeding risk, high stroke risk AF not anticoagulated on ED arrival, we found that rates of appropriate stroke prevention action increased over the 8-year study period. However, signficant gaps associated with patient sex and age were identified.

Our results demonstrate a significant disparity among women, who were 3.5% less likely to receive appropriate stroke action compared with men. These results are similar to the PINNACLE study that found women at all levels of risk had persistently lower rates of OAC use compared with men [29, 30]. With increased discussions on implicit bias, clinicians are increasingly aware of their own biases. This disparity highlights the need for increased interventions, namely gender bias training aimed at closing the gap to address gender and sex disparity.

The net clinical benefit of OAC may decrease with advancing age, where the quality of life-adjusted years of being on an OAC decreased compared with no treatment after age 92, where hemorrhage, stroke, or death were competing risks [31]. The risk of death from these other causes may be an important influence in declining net clinical benefit from OAC use. Thus, although physicians were less likely to take appropriate action according to current guidelines, physician intuition regarding those of advanced age may be in accordance with newer evidence.

Based on these recent studies, it appears that patients in the highest risk category (CHA2DS2-VASc score 6–9) would be more likely to possess characteristics that bias clinicians against OAC Action. For example, this higher risk stratification could account for age (1 point for age ≥ 65, 2 points for age ≥ 75), hypertension, and/or history of stroke, which potentially represents a greater co-morbidity burden given the significant overlap of these specific factors among HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc scores. However, the HAS-BLED score serves as a dynamic tool for assessing bleeding risk in patients rather than as a means to exclude high-risk patients from anticoagulation therapy. Its primary function is to highlight that modifiable bleeding risk factors are addressed, such as high blood pressure, and appropriately managed by outpatient clinicians. This approach allows for a more nuanced and patient-centered decision-making process regarding anticoagulation therapy, balancing the benefits of stroke prevention against the potential risks of bleeding complications [32]. Nevertheless, the ED is an acute care setting where close monitoring of reversible risk factors is not often a primary concern. Interesting results stem from the correlation of CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk score with physician prescribing. CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 4–5 were associated with 4.5% higher rates of OAC prescribing than a reference of CHA2DS2-VASc scores of 2–3; however, the rate of OAC prescribing for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 6–9 was not different from the lower risk group (score of 2–3). There was no difference in OAC prescribing for the highest risk category CHA2DS2-VASc score of 6–9 compared with the lowest category of CHA2DS2-VASc score. We hypothesize that while ED physicians recognize that higher scores equal a higher risk of stroke, risk–benefit ratios might also be considered. Furthermore, in the setting of age-related frailty and patient-specific goals of care, it is certainly possible that patients in the highest risk category received advanced care involving cardiology consultation, palliative care consultation, and/or subsequent cardiology follow-up, which could explain a lower rate of OAC prescribing by physicians.

Our study also attempted to determine if patient-physician race/ethnicity and language concordance influenced prescribing or referrals; however, no significant correlation was identified. We found that patients of Hispanic ethnicity received the highest rates of OAC Action (6.1% higher rates, all other factors including physician race, being equal). Although patients of Black/African American and Asian race had higher rates of OAC Action than referent non-Hispanic Whites, the differences were non-significant or borderline significant. Specific patient-physician racial/ethnic and/or language concordance could explain this, as some studies have indicated that racial concordance may improve medication adherence and account for higher-quality patient-physician communication [33, 34]. Reassuringly, we found no bias of physicians, regardless of race/ethnicity, towards any racial/ethnic minorities. Additionally, physician years of experience did not influence prescribing. Interestingly, for physician race/ethnicity, Asian physicians, specifically, were 4.8% more likely to take OAC Action compared with any other race/ethnicity, which may be related to culture-specific factors.

Our study also found that the rates of OAC prescribing increased starting in 2013 when dabigatran became available on the market. The trend of increased OAC prescribing correlates well with adding dabigatran to the system’s formulary in 2014, followed by apixaban in 2016. This suggests that ease of prescribing influences rates of prescribing. These findings are important in the US setting, where multiple insurers with varied coverages and high medication co-pays can make it challenging for physicians to identify cost-effective medications to encourage patient adherence. Improved insurer coverage nationwide, as well as approval and availability of generic OAC medications, could significantly increase prescribing and affordability and, thereby, increase patient access to medications and subsequent patient adherence.

Potential strategies to improve OAC prescribing for high-risk patients with AF include reducing patient costs of DOACs, enlisting assistance from AMS, and providing a clinical decision support (CDS) tool to help minimize bias in prescribing. The use of a CDS tool that includes a risk calculator (e.g., for CHA2DS2-VASc) could improve prescribing, as a calculator operates independent of bias (such as ageism, sexism, racism, etc.). Additionally, an integrated healthcare system further reduces the variability often seen in individual hospitals with regard to insurance, follow-up, formulary medications, etc. Thus, the gap in care that we observed is likely to be amplified in other settings and may require further strategies to improve important long-term clinical outcomes.

In 2021, we designed an ED-based CDS tool with an auto-populating CHA2DS2-VASc risk calculator to help physicians identify ED patients with AF who were eligible for OAC initiation at the time of ED discharge [35]. We evaluated the effectiveness of the CDS and its promotion to improve OAC initiation in a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized trial [36]. The use of CDS during the intervention phase worked as we had hypothesized: no gender difference was observed.

While ED-based CDS tools can assist with disparities, uptake can be challenging for those who remain uncertain whether CHA2DS2-VASc applies to ED populations, especially when professional guidelines for AF care changed in 2023 to include duration of AF as an indicator for risk and treatment. Future research should determine whether CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED risk scores can be used in acute care populations [7, 37].

Limitations

First, our results are limited to health plan members with prescription coverage benefits; however, our results are concordant with those of other settings. As an integrated health system, however, timely access to primary care physicians is more often available and could result in more prescriptions. Second, although stroke risk categories changed for women during this time period, namely Class I recommendation for OAC consideration was for a score of ≥ 2 in males and ≥ 3 in females, the Class IIa recommendation was for a score of ≥ 1 in males and ≥ 2 in females, our data remain in line with guideline recommendations and minimizes data reclassification. While guidelines state that bleeding risk scores should not be used at the patient level to determine eligibility for OACs, we are limited to aggregate data and were unable to consider benefits and harms on an individual level; we used HAS-BLED as a gross measurement of bleeding risk as an exclusion. Third, our results coincide with the introduction of DOACs and end in 2017 and hence may not reflect the current uptake of these medications. Fourth, we did not examine the impact of ED prescribing on subsequent clinical outcomes, which we intend to evaluate in future research. Fifth, we may have inadvertently included patients with a prior diagnosis of AF by using patients identified by ICD-9 initially and ICD-10 codes as of October 2015. However, even if the diagnosis had been made previously, the indication for OAC is still present, and the low OAC prescribing rate is still an important and relevant finding. Sixth, due to the nature of our KP databases, we used the filling of a prescription as a proxy for prescribing. Thus, physicians may have appropriately prescribed OAC without patients filling their prescriptions. This could lead to an underestimation of prescriptions. However, we would not expect the effect to invalidate the primary finding of a very low OAC treatment rate. Finally, we used structured data to capture co-morbidities. We did not have access to unstructured patient-level clinical data that may have influenced OAC prescribing (e.g., fall risk, ability to adhere to medications, etc.), which may have dissuaded OAC initiation for some patients.

Conclusion

Rates of AF thromboprophylaxis can be improved further by addressing sex and age disparities, as females and those age ≥ 75 (versus 65) were less likely to receive appropriate OAC Action.

Data availability

Aggregate data are available for sharing. However, individual-level data cannot be shared.

Change history

29 May 2025

The original publication was amended to correct a typographical error in Table.

References

Kea B, Alligood T, Manning V, Raitt M. A review of the relationship of atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2016;4:107–18.

Chao TF, Potpara TS, Lip GYH. Atrial fibrillation: stroke prevention. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;37:100797.

Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857–67.

McBride R. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study. Final results. Circulation. 1991;84:527–39.

Flaker G, Ezekowitz M, Yusuf S, Wallentin L, Noack H, Brueckmann M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared to warfarin in patients with paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation: results from the RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:854–5.

Tereshchenko LG, Henrikson CA, Cigarroa J, Steinberg JS. Comparative effectiveness of interventions for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a network meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003206.

Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:E1–156.

Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, Crijns HJGM, et al. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3314–414.

Wang Y, Guo Y, Qin M, Fan JIN, Tang M, Zhang X, et al. 2024 Chinese expert consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation in the elderly, endorsed by Geriatric Society of Chinese Medical Association (Cardiovascular Group) and Chinese Society of Geriatric Health Medicine (Cardiovascular Branch): executive summary. Thromb Haemost. 2024;124:897–911.

Fitch K, Broulette J, Pyenson B, Iwasaki K, Kwong WJ. Erratum: utilization of anticoagulation therapy in medicare patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2012;5:157–68.

Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, Cowell W, Lip GYH. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123:638–45.

Sammer CE, Lykens K, Singh KP. Physician characteristics and the reported effect of evidence-based practice guidelines. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:569–81.

Thind A, Feightner J, Stewart M, Thorpe C, Burt A. Who delivers preventive care as recommended? Analysis of physician and practice characteristics. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1574.

Christian AH, Mills T, Simpson SL, Mosca L. Quality of cardiovascular disease preventive care and physician/practice characteristics. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:231.

Kea B, Lin AL, Olshansky B, Malveau S, Fu R, Raitt M, et al. Stroke prophylaxis after a new emergency department diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:471–2.

Atzema CL, Austin PC, Miller E, Chong AS, Yun L, Dorian P. A population-based description of atrial fibrillation in the emergency department, 2002 to 2010. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:570.

Scott PA, Pancioli AM, Davis LA, Frederiksen SM, Eckman J. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and antithrombotic prophylaxis in emergency department patients. Stroke. 2002;33:2664.

Sandhu RK, Bakal JA, Ezekowitz JA, McAlister FA. The epidemiology of atrial fibrillation in adults depends on locale of diagnosis. Am Heart J. 2011;161:986.

Kea B, Waites BT, Lin A, Raitt M, Vinson DR, Ari N, et al. Practice gap in atrial fibrillation oral anticoagulation prescribing at emergency department home discharge. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:924–34.

Vinson DR, Warton EM, Mark DG, Ballard DW, Reed ME, Chettipally UK, et al. Thromboprophylaxis for patients with high-risk atrial fibrillation and flutter discharged from the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:346–60.

Kea B, Warton EM, Ballard DW, Mark DG, Reed ME, Rauchwerger AS, et al. Predictors of acute atrial fibrillation and flutter hospitalization across 7 U.S. emergency departments: a prospective study. J Atr Fibrillation. 2021;13:2355.

Scheuermeyer FX, Innes G, Pourvali R, Dewitt C, Grafstein E, Heslop C, et al. Missed opportunities for appropriate anticoagulation among emergency department patients with uncomplicated atrial fibrillation or flutter. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:557.

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, et al. AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in collaboration with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019;140:e125–51.

Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM, Andresen D, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137:263.

Singer DE, Chang Y, Borowsky LH, Fang MC, Pomernacki NK, Udaltsova N, et al. A new risk scheme to predict ischemic stroke and other thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: the ATRIA study stroke risk score. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000250.

Van Den Ham HA, Klungel OH, Singer DE, Leufkens HGM, Van Staa TP. Comparative performance of ATRIA, CHADS2, and CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores predicting stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: results from a national primary care database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1851.

Aspberg S, Chang Y, Atterman A, Bottai M, Go AS, Singer DE. Comparison of the ATRIA, CHADS2, and CHA2DS2-VASc stroke risk scores in predicting ischaemic stroke in a large Swedish cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3203.

Lip GYH, Frison L, Halperin JL, Lane DA. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile INR, elderly, drugs/alcohol concomitantly) score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:173.

Thompson LE, Maddox TM, Lei L, Grunwald GK, Bradley SM, Peterson PN, et al. Sex differences in the use of oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®) PINNACLE registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005801.

Strømnes LA, Ree H, Gjesdal K, Ariansen I. Sex differences in quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010992.

Shah SJ, Singer DE, Fang MC, Reynolds K, Go AS, Eckman MH. Net clinical benefit of oral anticoagulation among older adults with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12:e006212.

Lip GYH, Lane DA. Bleeding risk assessment in atrial fibrillation: observations on the use and misuse of bleeding risk scores. J Thromb Haemost. 2016.14:1711–4.

Adriano F, Burchette RJ, Ma AC, Sanchez A, Ma M. The relationship between racial/ethnic concordance and hypertension control. Perm J. 2021;25:20.

Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5:117.

Vinson DR, Rauchwerger AS, Karadi CA, Shan J, Warton EM, Zhang JY, et al. Clinical decision support to optimize care of patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter in the emergency department: protocol of a stepped-wedge cluster randomized pragmatic trial (O’CAFÉ trial). Trials. 2023;24:246.

Vinson DR, Warton EM, Durant EJ, Mark DG, Ballard DW, Hofmann ER, et al. Decision support intervention and anticoagulation for emergency department atrial fibrillation: the O’CAFÉ Stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2443097.

Kea B, Alligood T, Robinson C, Livingston J, Sun BC. Stroke prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation? To prescribe or not to prescribe-a qualitative study on the decisionmaking process of emergency department providers. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:759–71.

Spyropoulos AC, Viscusi A, Singhal N, et al. Features of electronic health records necessary for the delivery of optimized anticoagulant therapy: consensus of the EHR Task Force of the New York State Anticoagulation Coalition. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(1):113–24.

Nutescu EA, Wittkowsky AK, Witt DM, et al. Integrating electronic health records in the delivery of optimized anticoagulation therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(1):125–6.

An J, Niu F, Zheng C, et al. Warfarin management and outcomes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation within an integrated health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(6):700–12.

Witt DM, Sadler MA, Shanahan RL, Mazzoli G, Tillman DJ. Effect of a centralized clinical pharmacy anticoagulation service on the outcomes of anticoagulation therapy. Chest. 2005;127(5):1515–22.

Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236–9.

Simon J, Hawes E, Deyo Z, Bryant Shilliday B. Evaluation of prescribing and patient use of target-specific oral anticoagulants in the outpatient setting. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40:525–30.

Larock AS, Mullier F, Sennesael AL, et al. Appropriateness of prescribing dabigatran etexilate and rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a prospective study. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1258–68.

Gordon N, Lin T. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California adult member health survey. Perm J. 2016;20(4):34–42.

Davis AC, Voelkel JL, Remmers CL, et al. Comparing Kaiser permanente members to the general population: implications for generalizability of research. Perm J. 2023;27(2):87–98.

Lieu TA, Madvig PR. Strategies for building delivery science in an integrated health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1043–7.11.

Lieu TA, Platt R. Applied research and development in health care - time for a frameshift. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):710–3.

Bornstein S. An integrated EHR at Northern California Kaiser Permanente: pitfalls, challenges, and benefits experienced in transitioning. Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(3):318–25.

Chamberlain AM, Roger VL, Noseworthy PA, Chen LY, Weston SA, Jiang R, et al. Identification of incident atrial fibrillation from electronic medical records. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023237.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Adina S. Rauchwerger, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research, Pleasanton, California, for her unflagging administrative support.

Funding

This project was supported by the NHLBI K08 Mentored Training Grant (grant # 1K08HL140105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors (B.K., E.M.W., C.E.K., E.K., D.W.B., M.E.R., G.Y.H.L., M.R., B.C.S., D.R.V.) contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by B.K., D.R.V., and E.M.W. And E.M.W. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript, all figures, and tables were prepared by B.K., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors (B.K., E.M.W., C.E.K., E.K., D.W.B., M.E.R., G.Y.H.L., M.R., B.C.S., D.R.V.) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board approved this study, IRB # is 127945, and waived consent as this was a large database study using aggregate data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Anticoagulation services

Physicians initiating warfarin for patients with AF electronically consult their local Outpatient Anticoagulation Service. This pharmacy-managed, phone-based Service uses a computerized tracking system incorporated into KP Northern California’s comprehensive EHR to facilitate anticoagulation therapy [38, 39]. The pharmacists and their staff provide intensive patient education and initiate timely warfarin dose adjustments, order and track relevant laboratory tests as needed (e.g., international normalized ratios [INRs], complete blood count, and alanine transaminase), carefully follow patient symptoms and manage adverse events. They also track surgeries and office procedures to provide perioperative management and track the introduction of medications that interact with warfarin to adjust doses as indicated. This constellation of services is akin to similar programs in other KP regions of the U.S [40, 41].

The percent time in therapeutic range for the INR during the study period varied by the medical center and ranged from 64–68% early in the study to 70–74% late in the study, calculated with a 6-month look-back period using the Rosendaal linear interpolation method [42].What was learned from the management of patients on warfarin informed the design of a phone-based DOAC Pharmacy Service. Here pharmacists provide patients with medication education and consultation and ensure that necessary baseline labs are completed prior to DOAC initiation. The staff then follow patients for adverse effects, adherence, and therapeutic outcomes and ensure compliance with annual laboratory testing, including complete blood count, serum creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase levels. In addition to monitoring for drug-drug interactions and changes in renal function, the Service also monitors DOAC patients on hospital discharge and during office-based and in-hospital procedures. Both the warfarin and the DOAC programs perform ongoing quality assurance and outcome analysis.

Begun as a pilot in April 2014, the DAOC program was expanded facility by facility to become a system-wide DOAC Management Service by November 2016. The need for such a program was suggested from physician DOAC prescribing practices reported in other settings [43, 44].The Service is centered in three hubs across KP Northern California and provides comprehensive DOAC management for patients with on-label indications referred from prescribers. The DOAC Service also undertakes weekly queries of the system-wide pharmacy database to identify patients with new prescriptions of DOACs that had not been referred to the Service to offer assistance to the non-referring primary care physicians, most of whom place a secondary referral (Appendix 1. Figure 3).

Socioeconomic characteristics

KP health plan members share demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with the surrounding local and state populations [45, 46]. KP Northern California operates as a learning healthcare system with a strategic focus on delivery science and is supported by a robust, integrated electronic health record (EHR) system [47, 48]. This EHR encompasses comprehensive data from outpatient, emergency, inpatient, pharmacy, laboratory, and imaging services [49].

The outpatient OAC services launched a system-wide performance improvement project to optimize stroke prevention therapy for patients with non-valvular AF in Feb 2016. The project assists primary care physicians in identifying their patients not currently anticoagulated who may be eligible for thromboprophylaxis (e.g., CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2 without evident contraindications) as well as those patients currently anticoagulated for whom stroke prevention therapy may not be indicated (e.g., low-risk stroke scores).

Appendix 2

Methods of identifying variables

All 21 hospitals are on the same instance of the electronic health data record and are entered into Clarity databases, which can be used for research purposes. Prescription fill data is included in Clarity where prescriptions are filled within the Kaiser Permanente (KP) system. Patients within the KP system are part of an integrated health system with both insurance and healthcare under one system.

We identified OAC use based on prescription fills for OAC medication at KP pharmacies, INR testing, Anticoagulation Clinic appointments, and active medication lists. We used generic medication names to capture the medications of interest that were being used at KP during the study period.

We used ICD9 and ICD10 codes to identify patients with AF [35, 50]. We used ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for HAS-BLED and CHA2DS2-VASc, along with evidence of blood pressure medication fills for controlled hypertension, electronic health record (EHR) blood pressure measurements, EHR demographic data, EHR Lab data, and other EHR diagnoses and procedures.

Appendix 3

Facilities involved and their OAC Action rates within 14 days of encounter

Facility ID | No OAC Action within 14 days (n, %) | OAC Action within 14 days (n,%) | Total Cohort (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

A | 270 (79.2) | 71 (20.8) | 341 (3.6) |

B | 251 (78.0) | 71 (22.1) | 322 (3.4) |

C | 502 (77.4) | 147 (22.7) | 649 (6.8) |

D | 1026 (76.6) | 313 (23.4) | 1339 (13.9) |

E | 268 (76.1) | 84 (23.9) | 352 (3.7) |

F | 496 (74.4) | 171 (25.6) | 667 (7.0) |

G | 484 (74.4) | 167 (25.7) | 651 (6.8) |

H | 269 (74.3) | 93 (25.7) | 362 (3.8) |

I | 633 (73.4) | 230 (26.7) | 863 (9.0) |

J | 240 (73.0) | 89 (27.1) | 329 (3.4) |

K | 217 (72.3) | 83 (27.7) | 300 (3.1) |

L | 211 (71.8) | 83 (28.2) | 294 (3.1) |

M | 347 (71.3) | 140 (28.8) | 487 (5.1) |

N | 379 (70.8) | 156 (29.2) | 535 (5.6) |

O | 163 (70.3) | 69 (29.7) | 232 (2.4) |

P | 305 (69.5) | 134 (30.5) | 439 (4.6) |

Q | 281 (68.9) | 127 (31.1) | 408 (4.3) |

R | 72 (67.9) | 34 (32.1) | 106 (1.1) |

S | 246 (67.6) | 118 (32.4) | 364 (3.8) |

T | 179 (66.1) | 92 (34.0) | 271 (2.8) |

U | 187 (64.0) | 105 (36.0) | 292 (3.0) |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kea, B., Warton, E.M., Kutz, C.E. et al. Stroke prophylaxis after US emergency department diagnosis and discharge of patients with atrial fibrillation and flutter from 21 hospitals. Int J Emerg Med 18, 97 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-025-00887-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-025-00887-3