Abstract

Background

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), is a severe rash that often develops 2–6 weeks after the intake of the causative drug; however, its diagnosis is sometimes difficult. This article describes a case in which a patient with DIHS-induced multiple organ failure was successfully treated with blood purification therapy.

Case presentation

A male patient in his 60s was admitted to our hospital with autoimmune encephalitis. The patient was treated with steroid pulse therapy, acyclovir, levetiracetam, and phenytoin. From the 25th day, he presented with fever (≥ 38 °C) as well as miliary-sized erythema on the extremities and trunk, followed by erosions. DIHS and SJS were suspected; accordingly, levetiracetam, phenytoin, and acyclovir were discontinued. On the 30th day, his condition further deteriorated, and he was admitted to the intensive care unit for ventilatory management. The next day, he developed multi-organ failure and was started on hemodiafiltration (HDF) for acute kidney injury. Although he presented with hepatic dysfunction and the appearance of atypical lymphocytes, he did not meet the diagnostic criteria for DIHS or SJS/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Therefore, he was diagnosed with multi-organ failure caused by severe drug eruption and underwent a 3-day treatment with plasma exchange (PE) in addition to HDF. Accordingly, the patient was diagnosed with atypical DIHS. After being started on blood purification therapy, the skin rash began to disappear; moreover, the organ damage improved, with a gradual increase in urine output. Eventually, the patient was weaned off the ventilator and transferred to the hospital on the 101st day.

Conclusions

HDF + PE could effectively treat multi-organ failure caused by atypical DIHS, which is difficult to diagnose.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS) is a severe drug rash similar to Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) [1, 2].

It has a high mortality rate (10–20%) and is caused by a relatively limited number of drugs, including carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, zonisamide, allopurinol, salazosulfapyridine, diaphenyl sulfone, mexiletine, and minocycline [3]. There remains no established treatment for DIHS; however, its symptoms can be addressed by discontinuation of the suspected drugs, systemic steroids, steroid pulse therapy in severe cases, and supportive care such as blood purification for organ damage [4].

The symptoms of DIHS include fever, sore throat, general malaise, and loss of appetite. However, unlike ordinary drug eruptions, a prompt definitive diagnosis may be difficult since symptoms may develop at least 2 weeks after treatment initiation [3].

Case presentation

An Asian male patient in his 60s with autoimmune encephalitis was admitted to the neurology department. The patient had a history of hypertension and no history of diabetes. There was no family history. He did not have a smoking history. He was treated with steroid pulse therapy, acyclovir, levetiracetam, phenytoin, tazobactam/piperacillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, and vancomycin (VCM) for aspiration pneumonia and urinary tract infections that subsequently occurred. Although his consciousness disorder and general condition improved on the 37th day of admission (day 1), he developed a fever (≥ 38 °C) and scattered miliary-sized erythema on the extremities and trunk, with some showing fusion (Fig. 1A, left panels). There was no erythema on the face; additionally, there were no abnormalities in the ocular or oral mucosa.

Skin findings on day 1 and day 5 and chest radiograph and CT. Lesions in A the anterior thoracic region and upper left extremity. Miliary-sized erythema was observed on the extremities and trunk on day 1 (A). On day 5, there was expansion of the skin rash. B Chest radiography upon ICU admission (day 6, left panel) and ventilator weaning (day 24, right panel). The decreased permeability of the entire lung field, which could have been caused by the infiltrated fluid observed at ICU admission, improved at the time of weaning from ventilation. C Chest computed tomography (CT) at ICU admission. Frosted shadows in all lung fields and a large pleural effusion were observed

Since drug eruptions, including DIHS and SJS, were suspected, levetiracetam and phenytoin were discontinued, and topical steroids were started. On day 3, the suspected drug VCM was changed to linezolid. However, on day 5, his skin rash showed expansion (Fig. 1A, right panels), and he was started on steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone [mPSL] 1000 mg/day for 3 days). Moreover, his respiratory condition rapidly worsened, and he was started on noninvasive-positive pressure ventilation (NPPV). Drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation tests (DLST) were performed on levetiracetam and phenytoin on day 5.

On day 6, the NPPV could no longer keep the patient oxygenated. Upon admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 14 (eye, 4; verbal, 4; motor, 6). Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 38.5 °C, tachypnea (respiratory rate: 20 breaths/min), a heart rate of 103 bpm, and a blood pressure of 129/57 mmHg. On auscultation, there was a decrease in breath sounds and fine crackles in all lung fields; however, there was no heart murmur.

Laboratory tests upon admission to the ICU revealed an elevated inflammatory response (C-reactive protein: 16.7 mg/dL), increased levels of liver enzymes (aspartate transaminase, 48 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 86 IU/L), and decreased renal function (blood urea nitrogen, 30.6 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.17 mg/dL) (Table 1). Arterial blood gas analysis using NPPV revealed a decrease in the PaO2/FIO2 ratio (62.9 at FIO2 1.0). Chest radiography showed decreased permeability in both lung fields (Fig. 1B); furthermore, chest computed tomography revealed frosted shadows in all lung fields and extensive pleural effusion (Fig. 1C). He was placed on a ventilator due to multi-organ failure caused by severe drug eruption. At this point, the patient did not meet the diagnostic criteria for DIHS or SJS/TEN (Table 2); therefore, treatment was initiated for multi-organ failure due to severe drug eruption.

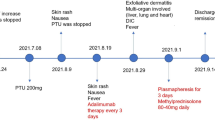

After admission to the ICU, the patient underwent 3-day treatment using intravenous immunoglobulin 5.0 g/day, meropenem, and sivelestat for severe drug eruption, severe pneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (Fig. 2). However, on day 7, his urine output rapidly declined; furthermore, he was diagnosed with KDIGO stage 3 acute kidney injury and was started on hemodiafiltration (HDF) using a polysulfone high-performance membrane (FDZ-21, Nikkiso, Tokyo, Japan) for 6 h daily. The blood, dialysate, and filtrate flow rates were maintained at 150–180 ml/min, 500 ml/min, and 25 ml/kg/daily, respectively. Sublood-BS (Fuso Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) was used as dialysate. On day 8, plasma exchange (PE) was performed for 3 days to ensure an effect on DIHS given the suspected multi-organ failure and SJS. PE was performed using a membrane plasma separator (OP-08, Asahi Kasei Medical, Tokyo, Japan) for 3 h daily with HDF. On the same day, steroid pulse therapy was terminated; accordingly, the mPSL dose was reduced to 125 mg/day and then tapered off. On day 8, the patient tested negative for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), which was a diagnostic criterion; however, the patient tested positive for Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and was started on ganciclovir. However, by day 11, he had an acute disseminated intravascular coagulation score of 4; therefore, recombinant human thrombomodulin was administered for 5 days, and recombinant antithrombin III formulation was administered for 3 days. On day 14, the patient met the diagnostic criteria for atypical DIHS (Table 2). Subsequently, the patient’s general condition improved, with HDF being terminated on day 18. A tracheostomy was performed on the same day. The ventilator was removed on day 24, and the patient was discharged from the ICU on day 28 and was then transferred to the hospital on day 68 after symptom improvement.

Clinical course. MEPM, meropenem; VCM, vancomycin; LZD, linezolid; GCV, ganciclovir; mPSL, methylprednisolone; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin; rTM, recombinant thrombomodulin; AT III, antithrombin III; PE, plasma exchange; HDF, hemodiafiltration; CMV, Cytomegalovirus; HHV-6, human herpesvirus 6; Cre, creatinine

Discussion and conclusions

Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to pharmaceuticals include various conditions, including DIHS and SJS/TEN [2]. There are seven and five diagnostic criteria for DIHS and SJS/TEN, respectively (Table 2) [1, 4]; however, both DIHS and SJS/TEN result in severe systemic symptoms; moreover, there may be overlapping cases [5], which impedes diagnosis in some cases. Furthermore, the difficulty in the diagnosis of DIHS could be attributed to rash, fever, and liver lesions usually disappearing after discontinuation of the suspected drug [3]. Since several of these diagnostic criteria are time-consuming to determine, the differential diagnosis of DIHS and SJS/TEN was difficult for our patient.

This patient was finally diagnosed with atypical DIHS. Although DLST can become positive after 1 month in patients with DIHS, none of the drugs in our case showed DLST positivity. Accordingly, the causative agent remained unknown.

In addition to HHV-6, reactivation of CMV, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus has been reported in patients with DIHS [6, 7]. In our patient’s case, CMV reactivation was observed, but it was not known whether this was due to DIHS or steroid therapy, a known risk factor for CMV reactivation. In addition, the patient did not show symptoms of active CMV disease. Therefore, although treatment with ganciclovir was ongoing, specific testing such as PCR for CMV and HHV six in bronchoalveolar lavage was not performed.

Since our patient showed multi-organ failure, HDF and PE were both administered to allow an effect on either DIHS or SJS/TEN. After PE therapy, the patient’s general condition and skin condition improved. Therefore, PE should be considered for severe drug eruptions that can cause multi-organ failure.

We encountered a case of atypical DIHS with multiple organ failure, which was resolved by acute blood purification therapy. Diagnosis of severe drug eruptions may be difficult during the early disease stages; accordingly, the treatment protocol should consider each of the probable diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- DIHS:

-

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome

- DLST:

-

Drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test

- HDF:

-

Hemodiafiltration

- HHV-6:

-

Human herpesvirus 6

- mPSL:

-

Methylprednisolone

- NPPV:

-

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation

- PE:

-

Plasma exchange

- SJS:

-

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- TEN:

-

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

- VCM:

-

Vancomycin

References

Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet. 2017;390:1996–2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6.

Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1272–85. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199411103311906.

Shiohara T, Kano Y, Hirahara K, Aoyama Y. Prediction and management of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:701–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425255.2017.1297422.

Shiohara T, Inaoka M, Kano Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): a reaction induced by a complex interplay among herpesviruses and antiviral and antidrug immune responses. Allergol Int. 2006;55:1–8. https://doi.org/10.2332/allergolint.55.1.

Perelló MI, de Maria Castro A, Nogueira Arraes AC, Conte S, Lacerda Pedrazzi D, Andrade Coelho Dias G, et al. Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions: diagnostic approach and genetic study in a Brazilian case series. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;54:207–17. https://doi.org/10.23822/EurAnnACI.1764-1489.193.

Kano Y, Hiraharas K, Sakuma K, Shiohara T. Several herpesviruses can reactivate in a severe drug-induced multiorgan reaction in the same sequential order as in graft-versus-host disease. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:301–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07238.x.

Shiohara T, Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Takahashi R. Crucial role of viral reactivation in the development of severe drug eruptions: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:192–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-014-8421-3.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the paramedical crew who shared the data they had obtained and allowed us to use the data for the writing of this report. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Funding

There are no sources of funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H Oiwa, SY, H Okada, MY, KR, KS, TM, TD, TS, and SO treated the patients. H Oiwa wrote the manuscript. H Okada revised and edited the manuscript accordingly. TS and SO supervised this study. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In Japan, approval from an ethics committee is not required for the reporting of cases. This case was reported in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects established by the government of Japan. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and from a patient’s legal guardian.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the consent form is available for the editor in chief of the International Journal of Emergency Medicine to review.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oiwa, H., Yoshida, S., Okada, H. et al. Atypical drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome with multiple organ failure rescued by combined acute blood purification therapy: a case report. Int J Emerg Med 16, 33 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-023-00511-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-023-00511-2