Abstract

A 70-year-old patient was referred to our emergency department with severe retrosternal pain after forceful vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a left-sided oesophageal rupture with accompanying pneumomediastinum and bilateral pleural effusions. Conservative treatment with cessation of oral intake, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, parenteral fluids and nutrition and left sided tube thoracostomy was initiated initially. After 5 days, however, the patient deteriorated. Follow-up CT scan demonstrated a mediastinal fluid collection as well as loculated pleural empyema. Open thoracotomy with mediastinal debridement and pleural drainage was performed, after which he made a slow but full recovery. Spontaneous oesophageal rupture due to an abrupt rise in intraluminal pressure caused by vomiting is also known as Boerhaave's syndrome. It is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition. Many patients present with atypical symptoms, and therefore, physicians should have a high index of suspicion in any patient presenting with vomiting and retrosternal pain. When Boerhaave's syndrome is suspected, a CT scan of the thorax and upper abdomen should be performed since treatment depends on clinical and radiological findings. Conservative management (cessation of oral intake, nasogastric decompression, administration of intravenous fluids and parenteral nutrition, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors and tube thoracostomies) may only be considered in patients with a contained rupture without systematic symptoms of infection. In these patients, endoscopic bridging of the tear with a self-expandable stent is also an option. Primary surgical repair (either by thoracotomy or by video assisted thoracoscopy (VATS)) should be considered when patients present with sepsis and/or large non-contained leaks or with severe mediastinal decontamination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spontaneous perforation of the oesophagus after forceful vomiting is also known as Boerhaave's syndrome. It most often occurs in the distal posterolateral aspect of the oesophagus [[1],[2]]. Many patients present with atypical symptoms like shock or respiratory distress, and findings on physical exam are often non-specific, with tachycardia, tachypnea or fever. Not surprisingly, Boerhaave's syndrome is often misdiagnosed as an aortic emergency, pericarditis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus, spontaneous pneumothorax, perforated peptic ulcer or pancreatitis [[3],[4]]. We outline the case of a 70-year-old man, who presented to the ED with retrosternal pain after vomiting, and discuss the clinical presentation, appropriate diagnostic steps and treatment strategies of this rare but potentially-life threatening condition.

Case presentation

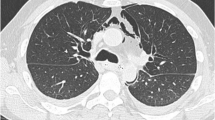

A 70-year-old man with a history of hypertension was referred to our emergency department with a severe retrosternal and upper abdominal pain that started after he had been vomiting several hours before presentation. At admission, he was diaphoretic and in respiratory distress. Blood pressure was 210/100 mmHg, pulse rate 95 beats/min, oxygen saturation was 95% and core temperature was 36.1°C. Physical examination revealed extensive cervical and thoracic subcutaneous emphysema but was otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory results were normal by the time of presentation. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a rupture in the left distal part of the oesophagus, a pneumomediastinum and left-sided pleural effusions (Figure 1). Conservative treatment, with cessation of oral intake, nasogastric suction, administration of intravenous fluids and parenteral nutrition, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors and drainage of the pleural effusion by left-sided thoracostomy was initiated in the ICU. After 5 days, however, he developed a fever. Follow-up CT scan demonstrated severe mediastinal contamination and left-sided loculated pleural empyema (Figure 2). Open thoracic surgery was performed with debridement and drainage of the mediastinum and the pleural cavity, after which he made a slow but full recovery.

Discussion

Many patients with Boerhaave's syndrome present with atypical symptoms like shock or respiratory distress, and findings on physical exam are often non-specific. The classical ‘Macklers triad’ consisting of (repeated) vomiting (79%), lower chest pain (83%) and subcutaneous emphysema (27%) is only present in a minority of the patients. Not surprisingly, it is often misdiagnosed as an aortic emergency, pericarditis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolus, spontaneous pneumothorax, perforated peptic ulcer or pancreatitis [[3],[4]].

Further radiological studies should be performed in any patient with a suspicion of Boerhaave's syndrome. Plain chest X-ray is in over 90% of the cases abnormal, with most often mediastinal or free peritoneal air as the initial manifestation [[5]]. Less often, with cervical oesophageal perforations, prevertebral or subcutaneous air may be present. Despite the high prevalence of plain chest X-ray abnormalities, contrast enhanced CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen is the preferred examination. Although it may not always directly localize the site of the perforation, it can detect oesophageal wall oedema, extra-oesophageal air, peri-oesophageal fluid collections and air and fluid in the pleural spaces and retroperitoneum with a higher sensitivity than plain chest X-ray [[6]]. Since CT findings (together with clinical parameters) are used to determine the degree of containment of the rupture and the accessibility of any fluid collections for percutaneous or surgical drainage, they help guide subsequent treatment.

Management of oesophageal perforations can be primarily conservative, endoscopic or surgical. The best treatment approach depends on the extent, location and containment of the perforation and the patients' delay in presentation and comorbidities. Conservative management (cessation of oral intake, nasogastric decompression, administration of intravenous fluids and parenteral nutrition, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors and tube thoracostomies) may be considered in patients with a contained rupture of the oesophagus without mediastinal or pleural contamination on imaging studies and without systemic symptoms of infection at the time of presentation [[7]–[10]]. However, only a minority of patients with Boerhaave's syndrome will fulfil these criteria (as opposed to, e.g. patients with iatrogenic perforations). As a result of forceful vomiting, pleural and/or mediastinal contamination with gastric content is usually present. Primary surgical or endoscopic treatment is therefore warranted in most patients.

Endoscopic (temporary) bridging of the tear with a self-expandable stent is an option in non-septic patients, as well as in patients with comorbidities that preclude surgery. However, although stenting has the potential for early oral feeding and a reduced hospital length of stay, case series published so far are small [[11]–[13]]. In addition, a recent study by Sweigert et al. [[14]] demonstrated that endoscopic stent insertion had a higher mortality than primary operative management. Primarily surgical intervention should take place in all patients with non-contained perforations, when comorbidities that preclude surgery [[9],[15]] are absent. The most successful surgical approach involves primary repair of the oesophagus, especially when the patient presents to the hospital early (within 24 h). Adequate mediastinal debridement can be done by open thoracotomy, or video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS), with results for VATS being comparable with those for open thoracotomy [[16],[17]]. In the presence of a diseased oesophagus, resection may be the appropriate treatment. No consensus exists whether patients can be managed with primary surgical repair when there is a significant delay in presentation or diagnosis, although a study carried out in a more heterogeneous group of patients with oesophageal ruptures could not demonstrate a relation between mortality risk and delay in presentation [[15]]. In retrospection, our patient might have benefitted from primary, instead of delayed surgery, since a pleural effusion was already present on the initial CT scan.

Conclusions

Our case clearly demonstrates the importance for any physician to have a high index of suspicion for Boerhaave's syndrome in any patient presenting with vomiting and retrosternal pain, and it stresses the importance of early aggressive (surgical) treatment.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal.

References

de Schipper JP, Pull ter Gunne A, Oostvogel HJ, van Laarhoven CJ: Spontaneous rupture of the oesophagus: Boerhaave's syndrome in 2008. Dig Surg 2009,26(1):1–6. 10.1159/000191283

Pate JW, Walker WA, Cole FH Jr, Owen EW, Johnson WH: Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1989, 47: 689–692. 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90119-7

Curci JJ, Horman MJ: Boerhaave's syndrome: the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Surg 1976,183(4):401–408. 10.1097/00000658-197604000-00013

Brauer RB, Liebermann-Meffert D, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Siewert JR: Boerhaave's syndrome: analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus 1997,10(1):64–68.

Ghanem N, Altehoefer C, Springer O, Furtwängler A, Kotter E, Schäfer O, Langer M: Radiological findings in Boerhaave's syndrome. Emerg Radiol 2003,10(1):8–13.

de Lutio di Castelguidone E, Merola S, Pinto A, Raissaki M, Gagliardi N, Romano L: Esophageal injuries: spectrum of multidetector row CT findings. Eur J Radiol 2006,59(3):344–348. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.04.027

Ivey TD, Simonowitz DA, Dillard DH, Miller DW Jr: Boerhaave syndrome. Successful conservative management in three patients with late presentation. Am J Surg 1981,141(5):531–533. 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90040-4

Carrott PW Jr, Low DE: Advances in the management of esophageal perforation. Thorac Surg Clin 2011,21(4):541–555. 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2011.08.002

Platel J, Thomas P, Giudicelli R, Lecuyer J, Giacoia A, Fuentes P: Esophageal perforations and ruptures: a plea for conservative treatment. Ann Chir 1997,51(6):611–616.

Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schäfer H, Bludau M, Brabender J, Lurje G, Herbold T, Holscher AH, Metzger R: Endoscopic therapy for esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with self-expendable metallic stent. Surg Endosc 2009,23(10):2258–2262. 10.1007/s00464-008-0302-5

Freeman RK, van Woerkom JM, Vyverberg A, Ascioti AJ: Esophageal stent placement for the treatment of spontaneous esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg 2009,88(1):194–198. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.004

Salo J, Sihvo E, Kauppi J, Räsänen J: Boerhaave's syndrome: lessons learned from 83 cases over three decades. Scand J Surg 2013,102(4):271–273. 10.1177/1457496913495338

Soriede J, Viste A: Esophageal perforation: diagnostic work-up and clinical decision-making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011, 19: 66–72. 10.1186/1757-7241-19-66

Sweigert M, Beattie R, Solymosi N, Booth K, Dubecz A, Muir A, Moskorz K, Stadlhuber RJ, Ofner D, McGuigan J, Stein HJ: Endoscopic stent insertion versus primary operative management for spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome): an international study comparing the outcome. Am Surg 2013,79(6):634–640.

Bhatia P, Fortin D, Inculet RI, Malthaner RA: Current concepts in the management of esophageal perforations: a twenty-seven year Canadian experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2011,92(1):209–215. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.131

Scott HJ, Rosin RD: Thoracoscopic repair of a transmural rupture of the oesophagus (Boerhaave’s syndrome). J R Soc Med 1995,88(7):414–415.

Haveman JW, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Kobold JP, van Dam GM, Plukker JT, Hofker HS: Adequate debridement and drainage of the mediastinum using open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for Boerhaave's syndrome. Surg Endosc 2011,25(8):2492–2497. 10.1007/s00464-011-1571-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GvdW and EtA drafted the manuscript. GvdW, MW and MvL were directly involved in patient care and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Weg, G., Wikkeling, M., van Leeuwen, M. et al. A rare case of oesophageal rupture: Boerhaave's syndrome. Int J Emerg Med 7, 27 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-014-0027-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-014-0027-2