Abstract

Background

Over a decade ago, the first nationally representative probability survey concerning the teaching of evolution revealed disquieting facts about evolution education in the United States. This 2007 survey found that only about one in three public high school biology teachers presented evolution consistently with the recommendations of the nation’s leading scientific authorities. And about 13% of the teachers emphasized to their students that creationism was a valid scientific alternative to modern evolutionary biology. In this paper, we investigate how the quality of evolution teaching, as measured by teachers’ reports of their teaching practices with regard to evolution and creationism, has changed in the intervening 12 years.

Results

We find substantial reductions in overtly creationist instruction and in the number of teachers who send mixed messages that legitimate creationism as a valid scientific alternative to evolutionary biology. We also report a substantial increase in the time that high school teachers devote to human evolution and general evolutionary processes. We show that these changes reflect both generational replacement—from teachers who are new to the profession—and changes in teaching practices among those who were teaching in the pre-Kitzmiller era.

Conclusion

Adoption of the Next Generation Science Standards, along with improvements in pre-service teacher education and in-service teacher professional development, appears to have contributed to a large reduction in both creationist instruction and mixed messages that could lead students to think that creationism is a scientific perspective. Combined with teachers devoting more hours to evolution—including human evolution—instruction at the high school level has improved by these measures since the last national survey in 2007.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over a decade ago, the first nationally representative probability survey concerning the teaching of evolution revealed disquieting facts about evolution education in the United States. This 2007 survey found that only about one in three public high school biology teachers presented evolution consistently with the recommendations of the nation’s leading scientific authorities. And about 13% of the teachers emphasized to their students that creationism was a valid scientific alternative to modern evolutionary biology (Berkman and Plutzer 2011). In this paper, we investigate how the quality of evolution teaching, as measured by teachers’ reports of their teaching practices with regard to evolution and creationism, has changed in the intervening 12 years.

Revisiting the state of evolution education is important because the 2007 survey was in the field less than 2 years after the well-publicized Kitzmiller v. Dover case (400 F. Supp. 2d 707 [M.D. Pa. 2005]) was tried in a US federal court. The decision in that case was unambiguous: creationism—even in its newest guise of intelligent design—was religious in nature and could not be taught in public school science classrooms. Kitzmiller v. Dover represented the latest in a long line of cases protecting the teaching of evolution and appeared to put an end to any serious efforts to introduce creationism overtly. Furthermore, the last 10 years have seen significant efforts to promote the teaching of evolution. Organizations including the National Science Teaching Association, the National Association of Biology Teachers, and the National Academy of Sciences have produced statements, reports, classroom resources, professional development opportunities and more to advance the inclusion of evolution in the nation’s classrooms.

Equally important, the 2010s saw the development and refinement of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS Lead States 2013), which are based on the best available evidence about how people learn science. The NGSS accord evolution a central role in biology and life science education and have been adopted so far by 20 states (plus the District of Columbia); a further 24 states have based their standards on the same framework (National Research Council 2012) on which the NGSS is based and thus generally have a comparable treatment of evolution. The NGSS are increasingly reflected in textbooks, on-line resources, pre-service teacher education, and in-service teacher professional development opportunities, and the National Science Teaching Association (2013) is firmly in their favor.

The apparent end of legal battles over creationism and the active promotion of the teaching of evolution, along with the adoption and implementation of standards with a forthright treatment of evolution, suggest that teaching practices should have changed substantially. Yet the barriers to effective teaching are numerous (e.g., Branch et al. 2010; Sickel and Friedrichsen 2013; Glaze and Goldston 2015), so progress is by no means guaranteed. We put these two possibilities—improvement in evolution education or not—to the test by answering four key questions:

Is evolution being taught more accurately and completely today than in 2007?

With the Kitzmiller trial more than a decade in the past, have intelligent design and other manifestations of creationism faded from the classroom?

Is the teaching of evolution discernibly different in states that adopted NGSS in comparison to states that did not?

What actions are likely to bring about continued improvement in evolution teaching in US high schools?

In answering these questions, we also explore several additional factors that provide context for understanding the patterns of change and continuity. These include comparing teachers who began their careers before 2007 (almost all beginning before Kitzmiller) to those beginning after, and examining how completion of evolution-relevant professional development classes is linked to teaching practices.

To address these questions, we rely on results from a new national survey of science teachers that sought to answer these, and other, questions. To maximize comparability, the 2019 Survey of American Science Teachers adopted the same sampling strategy of the 2007 National Survey of High School Biology Teachers (Berkman et al. 2008; Berkman and Plutzer 2010), surveying a random sample of high school biology teachers; the 2019 questionnaire included most of the key questions originally asked in 2007.

This report proceeds in three steps. First, we describe the research design of the 2019 survey (with more details on materials and methods in the Appendix). Second, we compare key descriptive statistics from the new study with the corresponding statistics from 2007. Third, we provide additional detail on several important factors influencing the curricular decisions made by teachers today. We conclude with a discussion of implications for policy and pedagogy.

Methods

Fielded between February and May of 2019, the 2019 Survey of American Science Teachers included both a high school and a middle school sample. The former is the focus of this paper and is based on a probability sample of public high school biology (and life science) teachers. The sample was drawn, based on investigator specifications, from a national teacher file maintained by MDR (Market Data Retrieval, a Dunn and Bradstreet direct mail firm that maintains the largest mailing list of educators in the US). To ensure national coverage, the national list of 30,847 high school biology teachers was first stratified by state and urban/suburban/other location. With the District of Columbia serving as a single stratum, this produced 151 segments. Within each segment, we selected a random sample with a sampling probability of roughly 0.08, yielding an initial set of 2503 high school biology teacher names and addresses.

Following the 2007 protocol exactly, and consistent with best practices for mail surveys (Dillman et al. 2014), we then sent each teacher an advance prenotification letter explaining the survey and telling them that a large survey packet would arrive in a few days. The packet included a cover letter, a token pre-incentive (a $2 bill), a 12-page survey booklet, and a postage-paid return envelope. One week later a reminder postcard was sent, and a complete replacement packet (though without an incentive) 2 weeks after that. In the week after the replacement packet was mailed, we emailed reminders to the roughly 85% of non-responding teachers for whom we had valid emails. Two email reminders and one final postcard—saying that the study was about to close—followed.

The overall response rate was 40% (using AAPOR response rate formula #4). To place this in context, sample surveys of teachers vary considerably in their overall response rate, ranging from the low single digits (Puhl et al. 2016; Troia and Graham 2016; Davis et al. 2017; Dragowski et al. 2016) and the mid-teens (Dragowski et al. 2016; Hart et al. 2017) to Department of Education survey programs that approach 70% (National Center for Education Statistics N.d., 2018; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015). In that light, our response rate is at the high end of results achieved outside of government-sponsored studies. However, survey scientists have sought to discourage a heavy reliance on response rates as indicators or data quality. Indeed, scores of studies show that there is no simple relationship between response rates and Total Survey Error or response bias (e.g., Keeter et al. 2000; Groves and Peytcheva 2008; Keeter 2018), leading to a greater focus on direct measures of a sample’s representativeness. To this end, we conducted a detailed non-response audit, and found that the responding teachers were broadly representative of the target population. Details are provided in the Appendix (e.g., Table 15).

We augmented the design weights with a non-response adjustment, and we report weighted estimates throughout this report, although the unweighted results are almost always similar. Full details on the methods of contact, the non-response audit, methods of weight calculation are provided in the Appendix.

Results

In comparing the statistics from the 2019 sample of high school biology teachers to the corresponding statistics from 2007, we find some similarities but also some important changes. As reported in Table 1, more than 95% of high school biology teachers reported covering evolution at least to some degree in both years. The number of teachers reporting not teaching evolution at all increased slightly, but this may be due to a change in classification of teacher titles so that our survey included teachers who do not teach core classes in general biology. Most dramatically, we find a 60% increase in the mean number of class hours reported as devoted to human evolution, from 4.1 to 7.7 class hours. While having the potential to exacerbate religiously-driven opposition, human evolution also provides a particularly “enjoyable, engaging, and effective way to teach core evolutionary concepts” (Pobiner 2016, 262). In addition, reported instruction in general evolutionary processes rose 25%, from 9.8 class hours in 2007 to 12.4 class hours, driven by an increase in the number of teachers reporting devoting ten or more hours to evolution.

The messages conveyed to students

A key feature of the 2007 survey was a set of questions concerning the messages conveyed by teachers with respect to evolution’s scientific foundation and its centrality to modern biology. Those questions, with the same wording and in the same order, were included in the 2019 survey as well. Table 2 reports on three key items that the surveys used to identify distinct messages about evolution. The first two concern the centrality of evolution. The first asked teachers to agree or disagree that it is “possible to offer an excellent general biology course for high school students that includes no mention of Darwin or evolutionary theory.” At the high school level, we see virtually no change at all, with 82–83% rejecting this idea in both 2007 and 2019. The second question asked whether evolution served as a unifying theme for their course. At the high school level, we see some small change in those strongly agreeing, from 26 to 31%, a difference that is marginally significant.Footnote 1

The third panel of the table reports on perhaps the key question on how teachers convey the science of evolution—whether teachers “emphasize the broad consensus that evolution is a fact, even as scientists disagree about the specific mechanisms through which evolution occurred.”

Here the data for high school teachers show considerable movement. The percentage of teachers disagreeing with this statement has dropped from 22 to 13% and the percentage agreeing rose from 74 to 79%. Most notably, the percentage of teachers who strongly agree has shot up from 30 to 47%. Based on these data, it appears that many more high school students are being exposed to evolutionary biology taught as settled science today than 12 years ago.

Creationism in the classroom

We now turn to creationism in the classroom. Following the question wording used in the 2007 survey, we asked teachers to report on the number of class sessions they devote to “creationism or intelligent design.”Footnote 2 Table 3 shows that fewer teachers report discussing creationism and intelligent design in high school biology classes, down from 23 to 14% (the 95% margin of error for each percentage, accounting for design effects, is under ± 3%). As in 2007, the modal teacher who reported covering creationism or intelligent design devoted 1–2 class sessions to the topic.

But simply devoting time to creationism might not imply a rejection of modern science. That is because some teachers may raise the topic of creationism in the context of explaining why it is not scientific (Nelson et al. 2019). To see the full range of messages conveyed to students, we turn to two questions asking about creationist perspectives.

These questions overlap, with the first posing the statement “I emphasize that intelligent design is a valid, scientific alternative to Darwinian explanations for the origin of species,” and the second “I emphasize that many reputable scientists view creationism or intelligent design as valid alternatives to Darwinian theory.”Footnote 3 That is, they ask about the teacher making assertions without and with appeals to scientific authority. The results are reported in Table 4.

Overall, we find that 18% of high school biology teachers agreed with at least one of the two statements, down slightly from 21% in 2007—while this difference might hint at a subtle change, the drop does not achieve conventional levels of statistical significance. It is notable that the number of teachers disagreeing with the first statement has increased markedly, from 32 to 58%, with the change largely driven by a sharp drop in the number of teachers who declined to answer this question, from 53 to 29%. Also notable is the sharp increase in the percentage of teachers strongly disagreeing with each statement. This result reinforces the conclusion that more teachers are confident in their acceptance of evolution and rejection of creationism. Taken together with the decline in the percentage of teachers devoting class hours to creationism, it is likely that the topic is being raised outside of formal lesson plans or as part of teaching the nature of science rather than as a scientifically valid alternative to evolution.

The consistency of messages teachers send to students

Each of these questions reveals a different component of change. However, a clearer picture emerges if we summarize the results. To do so, we assigned teachers to four categories based on themes they agreed that they emphasized to their students.Footnote 4 The first group are those who reported that they emphasized to their students that evolution is established science: all teachers who said that they “emphasize the broad consensus that evolution is a fact, even as scientists disagree about the specific mechanisms through which evolution occurred” and did not report sending any pro-creationism messages. Exclusively pro-creationist teachers are all who agreed that they emphasized creationism as a “valid scientific alternative” to their students. All other teachers we classified as either “avoiders” (those who agreed with none of the relevant statements) or sending “mixed messages” (those who told us they emphasize both positions).

We applied this typology to both the original 2007 data and the 2019 survey to assess change over time, and the results are summarized in Fig. 1. We find several important shifts. First, we see a dramatic increase in teachers who reported emphasizing “the broad consensus that evolution is a fact, even as scientists disagree about the specific mechanisms,” while giving no credence to creationism as science (green squares). This group increased from 51 to 67%. We also see a drop in those reporting exclusively emphasizing creationism as a “valid scientific alternative” (red circles), from 8.6 to 5.6%. Although the 95% confidence intervals overlap slightly, the null hypothesis that the proportions are the same in a common population is rejected at the 0.05 level (t = 2.35; or t = 2.08 after accounting for design effects). Of perhaps more importance, the percentage of teachers reporting sending mixed messages (orange diamonds) dropped sharply from 23 to 12% and the number of teachers reporting as avoiders (black triangles) also declined (18 to 15%).

These shifts are sizable. If extrapolated to the roughly 3.9 million students who will complete a general biology course in 9th or 10th grade each year,Footnote 5 then 116,000 fewer children are being exposed to exclusively pro-creationist messages and 418,000 fewer to mixed messages than 12 years previously. Moreover, with teachers spending an average of 5 additional hours on human and general evolution than in 2007, the opportunities for students to learn the science of evolutionary biology in an unvarnished and unapologetic way have increased substantially.

What accounts for the shifts?

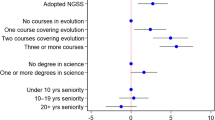

To look for factors that might explain these shifts in the context of broader changes in society and science education, we explored three additional research questions. First, whether teaching practices vis-à-vis evolution are different in states that adopted the Next Generation Science Standards and states that did not. Second, whether teachers who were not yet teaching at the time of the initial survey are different vis-à-vis teaching evolution from teachers with greater seniority. And, third, whether teachers who have participated in continuing education on evolution teach evolution in distinctive ways from those who did not.

The role of the NGSS

Using a classification published by the National Science Teaching Association (https://ngss.nsta.org/About.aspx), we distinguished among states that have officially adopted the NGSS, states that have adopted standards based on the same framework on which the NGSS are based [viz., the National Research Council’s A Framework for K–12 Science Education (2012)], and states that have adopted standards not based on the Framework.

Table 5 first shows the classification of teachers from 2007 based on whether their states would later adopt the NGSS. It shows that teaching practices did not vary much; if anything, teachers in states that would later adopt NGSS were less likely to report teaching evolution forthrightly and more likely to report conveying mixed messages.

By 2019 this was no longer the case. The percentage of those reporting teaching evolution as established science is slightly higher in NGSS-adopting states (69%) than in non-NGSS-adopting states (66%; a difference that is not statistically significant). More dramatically, the percentage of teachers reporting conveying mixed messages has dropped dramatically in NGSS and NGSS-framework states compared to the percentage in non-framework states.

The role of seniority

Long-term trends such as these can come about through generational replacement, behavioral change, or some combination of these. Science faculties now include a substantial number of teachers who were not yet in the profession in 2007. These newer teachers would have completed their pre-service education and taken in-service professional development entirely after Kitzmiller, and many of the newest teachers’ pre-service education would have reflected NGSS. So the change we observe could be entirely due to new teachers replacing older ones, with the new teachers especially strong in their scientific approach to evolution. On the other hand, the change could have occurred because those already in the profession changed their teaching approach—for example in response to new state standards or textbooks, or because they were given opportunities for, or required to attend, professional development on evolution.

All teachers reported the number of years they have been in the profession, and we used these data to identify teachers who were already in the science classroom in 2007 and those who were not. The results, shown in Table 6, show no differences based on seniority. That tells us that the over-time gains have come from both those new to the profession and those with longer tenure. And these more senior teachers must have changed their approach to teaching evolution.

Next Generation Science Standards, seniority, and time devoted to evolution

Thus far, we have shown that many more teachers report forthrightly teaching evolution as established science, and fewer report sending mixed messages. The evidence suggests that the NGSS may be playing a modest role and that the shift driven both by the entry of new cohorts of teachers and changing practices of more senior educators. We next examine how NGSS adoption and seniority are related to the time teachers report devoting to evolution. Table 7 presents the mean number of class hours that teachers report devoting to human evolution and general evolution (exclusive of human evolution), by their seniority and their state’s NGSS adoption.

The top panel, focusing on general evolution. shows that teachers in NGSS-adopting states report devoting about 30% more class hours to evolution than teachers in non-Framework states (states adopting the standards based on the Framework are in between). This pattern is uniform across levels of seniority, and seniority has no independent effect.

The middle panel shows that younger teachers report devoting more time to human evolution than their more senior colleagues, and that teachers in NGSS-adopting states report devoting more time to human evolution than their colleagues in states with non-NGSS standards. Taken together, these results suggest that the less ambiguous messages are being amplified and reinforced by more class time.

Overall, then, it appears that teachers with substantial seniority are changing their approach to teaching evolution and teaching it for more hours, while at the same time, newer teachers are arriving prepared to teach evolution as settled science and now devote more time to evolution than their senior colleagues. In addition, all teachers in NGSS-adopting states report devoting a little more time to evolution than teachers in other states. There are many potential explanations for these patterns, but an important one is the role of formal education: college-level courses for pre-service teachers and professional development classes for experienced educators.

The role of college coursework and professional development

Teachers were asked to report, retrospectively, the number of full college courses focused on evolution, the number of college courses that included evolution as a topic, and the number of continuing education courses focused on evolution they took. Although the number of teachers in some of the subgroups are so small as to make some inferences uncertain, it is apparent that reporting more coursework in each of these categories was positively correlated with reporting teaching evolution as settled science and negatively associated with reporting avoidance (see Table 8).

We next examined whether enrollment in these classes is higher in NGSS-adopting states to explore how the NGSS may have contributed to the changes evident in the quality of teaching evolution, as measured by teachers’ reports of their teaching practices with regard to evolution and creationism, at the high school level. To that end, Table 9 reports the mean number of evolution-related coursework by teacher seniority and their state’s NGSS adoption. While the number of courses or professional development opportunities completed by newer teachers appears unrelated to the adoption of the NGSS, senior teachers in NGSS and Framework states have received significantly more education in evolution than their peers in non-NGSS states. The top panel shows that teachers in NGSS-adopting states reported completing significantly more evolution-focused classes than teachers in non-NGSS-adopting states (two-tailed p = 0.017), an effect primarily driven by more senior teachers (though the interaction does not achieve statistical significance).

The bottom panel tells a similar story. Veteran teachers in NGSS-adopting or Framework states were more likely to report completing continuing education classes on the topic of evolution—1.8 and 1.7 courses respectively in comparison to 1.3 courses for all other teachers. While we lack the kind of prospective study that could test all causal effects rigorously, the pattern suggests that the NGSS have contributed to the improvements in the teaching of evolution and that one key mechanism involves teachers with high seniority completing professional development courses that help them adapt to the NGSS. In contrast, lower seniority teachers in NGSS-adopting states seem to be teaching evolution as settled science more than the prior generation did in 2007, and this is probably due to colleges of education better preparing them to teach evolution.Footnote 6

Personal values and evolution pedagogy

Based on their 2007 study, Berkman and Plutzer (2010) argued that teachers’ personal opinions affected the instruction students receive far more than did state standards. This was especially evident for those teachers who advocated for creationism as a valid scientific alternative. To see whether this is still the case, we examine two additional factors. The first is measured by the standard polling question that asked teachers to select among three common beliefs about human evolution; the second is measured by a standard question about Biblical interpretation.

The results, summarized in Table 10, show how important personal beliefs remain today. Twelve percent of those reporting sending mixed messages, 25% of those reporting avoidance, and 60% of teachers reporting endorsing creationism reject even God-guided evolution and personally believe in a creationist perspective. Likewise, those who agreed with a literalist interpretation of scripture are much more prevalent among those reporting sending mixed or exclusively creationist messages. These results suggest that there is a small “hard core” of creationist educators for whom accurately teaching evolution conflicts with their personal faith commitments. But the results also suggest that most teachers reporting avoidance and sending mixed messages are not in this hard core, which suggests that their teaching may be improved by providing increased learning opportunities.

Notably, the percentage of teachers who endorse the creationist option in this question has fallen, from 16% in the 2007 sample to just 10.5% in 2019. This change is largely due to generational replacement, as only 7% of the more recent teachers express this view. If this trend continues, the number of strong advocates for creationism in public school science classrooms will continue to decline.

Discussion

This paper compared results of two surveys of public high school biology teachers that used identical sampling procedures and identical survey questions. In the 12 years between the two surveys, evolution instruction in US public high schools has improved substantially, as measured by teachers’ reports of their teaching practices with regard to evolution and creationism. Many fewer teachers report sending mixed messages and many more report emphasizing to their students “the broad consensus that evolution is a fact, even as scientists disagree about the specific mechanisms through which evolution occurred.” In addition, teachers report devoting substantially more class hours to evolution, including human evolution. New teachers who entered the profession after 2007 are doing an especially good job, as measured by their reports of their teaching practices with regard to evolution and creationism, but teachers with more seniority have also improved on this score and have benefited from professional development opportunities on evolution, particularly if they work in NGSS-adopting states.

But there is still clearly room for further improvement. The teachers classified as teaching evolution as settled science are a diverse group: most report devoting considerable time to human evolution, but about 16% report not covering it at all. Most agree that evolution serves as a unifying theme for their course, but 18% do not. Of even greater concern, a substantial number of teachers continue to either avoid evolution altogether or communicate mixed messages that can serve to legitimize non-scientific alternatives in the minds of their students, judging from the results of the 2019 survey. Noting that such teachers “fail to explain the nature of scientific inquiry, undermine the authority of established experts, and legitimize creationist arguments, even if unintentionally,” Berkman and Plutzer (2011, p. 405) suggested that they “may play a far more important role in hindering scientific literacy in the United States than the smaller number of explicit creationists.” Especially in light of the dwindling number of explicit creationists among public high school biology teachers seen in the 2019 survey, this concern is even more valid today. It is therefore encouraging that increasing attention is being paid to the need to equip both pre-service teachers and in-service teachers with the wherewithal to teach evolution effectively despite the social controversies surrounding the topic (see, e.g., Borgerding and Dagistan 2018 on pre-service teachers and Friedrichsen et al. 2016 on in-service teachers).

Conclusion

The substantial improvements suggest that current reforms in state standards, pre-service teacher education, and in-service teacher professional development are having their intended effects, at least in the broad strokes that this survey is able to capture. Thus, scientific and educational institutions should continue their efforts to add scientific rigor to standards, seek out and promote textbooks and other resources that cover evolution thoroughly, support professional development opportunities for teachers, and support teachers who come under pressure from parental or community members who resist evolution instruction or advocate for the inclusion of creationism. These efforts should, of course, be informed by evidence of the sort gathered by this survey. In that light, an important priority for future research will be better understanding how and why teachers continue to convey mixed messages. More granular research that examines mixed messages and how they are introduced into lesson plans or improvised in response to classroom dynamics would be especially valuable. The evidence that many of the teachers who report avoiding or sending mixed messages about evolution do not themselves hold creationist beliefs suggests that additional instruction both in evolution content and best pedagogical practices could substantially improve their evolution teaching. Equally important will be assessments of the impact such messages have on student learning and their preparation for college-level STEM education. More generally, it seems especially important to identify strategies that are helpful in not only discouraging the advocacy of creationism but also increasing the numbers of teachers who consistently convey a scientifically accurate and pedagogically appropriate presentation of evolution in the high school biology classroom.

Availability of data and materials

Replication data set, codebook, and code to replicate all tables and figures will be made available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/2019_Science_Teachers/ no later than 12 months after publication. Investigators may request access to the data sooner.

Notes

Significant at the 0.05 level in a two-tailed t test, ignoring design effects. With an estimated design effect of DEFT = 1.2, the difference is no longer significant at conventional levels.

We recognize that intelligent design is simply a strategy for promoting creationism, but we maintained this wording to maximize the comparability of our survey results with those from the earlier study.

Advocates for creationism have put a lot of effort into claiming that they have real scientists doing real science on their side, so the term “reputable” potentially plays to that rhetoric and may be interpreted differently by different teachers. We retained this wording in the interests of consistency with the 2007 survey.

Berkman and Plutzer (2011) used a different typology. There, advocates for creationism were defined as teachers who devoted a formal class lesson to creationism as well as agreed with at least one of the statements listed in Table 4, while advocates for evolution were defined as teachers who agreed (or disagreed in the case of the first) with the statements listed in Table 2 and strongly agreed (or disagreed) with at least one. This scheme resulted in a large heterogeneous middle category and misclassified, in our view, many teachers who send mixed messages as advocates of creationism, so we have not used it here. However, our basic conclusions would be unchanged if we were to use this coarser classification system.

General biology is nearly universal, completed by 97% of secondary students. Cohort size estimate from National Center for Education Statistics (2019).

A surprising result of the 2019 survey is the sharp increase in the amount of time devoted to human evolution: while the number of class hours devoted to general topics in evolution increased by over 25% between 2007 and 2019, the number of class hours devoted to human evolution increased by over 60%. Human evolution is not specifically mentioned in the NGSS, so the increase is not likely to be directly attributable to the adoption of the NGSS. Teachers were not asked specifically about the presence of human evolution in their pre-service or in-service coursework, so further research will be required to ascertain the factors responsible for the increase in the coverage of human evolution.

Extrapolating, had we taken the time to track down the gender of all 548 teachers through web searches, LinkedIn, etc., we would have gotten an additional 37 completed surveys.

References

American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9th edition. AAPOR. 2006. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf.

Berkman MB, Pacheco JS, Plutzer E. Evolution and creationism in America’s classrooms: a national portrait. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:5.

Berkman MB, Plutzer E. Defeating creationism in the courtroom, but not in the classroom. Science. 2011;331(6016):404–5.

Berkman M, Plutzer E. Evolution, creationism, and the battle to control America’s classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Borgerding LA, Dagistan M. Pre-service science teachers’ concerns and approaches for teaching socioscientific and controversial issues. J Sci Teach Educ. 2018;29:283–306.

Branch G, Scott EC, Rosenau J. Dispatches from the evolution wars: shifting tactics and expanding battlefields. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2010;11:317–38.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study 2014. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/pdf/SHPPS-508-final_101315.pdf.

Davis JD, Choppin J, McDuffie AR, Drake C. Middle school mathematics teachers’ perceptions of the common core state standards for mathematics and its impact on the instructional environment. School Sci Math. 2017;117:239–49.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. New York: Wiley; 2014.

Dragowski EA, McCabe PC, Rubinson F. Educators’ reports on incidence of harassment and advocacy toward LGBTQ students. Psychol Schools. 2016;53:127–42.

Friedrichsen PJ, Linke N, Barnett E. Biology teachers’ professional development needs for teaching evolution. Sci Educ. 2016;25:51–61.

Glaze AL, Goldston MJ. US science teaching and learning of evolution: a critical review of the literature 2000–2014. Sci Educ. 2015;99:501–5018.

Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: a meta-analysis. Public Opin Q. 2008;72:167–89.

Hart KC, Fabiano GA, Evans SW, Manos MJ, Hannah JN, Vujnovic RK. Elementary and middle school teachers’ self-reported use of positive behavioral supports for children with ADHD: a national survey. J Emot Behav Disord. 2017;25:246–56.

Keeter S, Miller C, Kohut A, Groves RM, Presser S. Consequences of reducing nonresponse in a national telephone survey. Public Opin Q. 2000;64:125–48.

Keeter S. Evidence about the accuracy of surveys in the face of declining response rates. In: Vannette DL, Krosnick JA, editors. Palgrave Handbook Of Survey Research. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018. p. 19–22.

Lang SN, Mouzourou C, Jeon L, Buettner CK, Hur E. Preschool teachers’ professional training, observational feedback, child-centered beliefs and motivation: direct and indirect associations with social and emotional responsiveness. Child Youth Care Forum. 2017;46:69–90.

National Center for Education Statistics. Table 203.10: Enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by level and grade: Selected years, fall 1980 through fall 2028. Digest of Education Statistics (2018 ed.). 2019. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_203.10.asp.

National Center for Education Statistics. School and Staffing Survey Methodology Report. 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/sass/methods1112.asp.

National Research Council. A Framework for K–12 science education: practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. The National Academies Press; 2012.

National Science Teaching Association. NSTA Position Statement: The Next Generation Science Standards. 2013. https://www.nsta.org/about/positions/ngss.aspx.

Nelson CE, Scharmann LC, Beard J, Flammer LI. The nature of science as a foundation for fostering a better understanding of evolution. Evo Edu Outreach. 2019;12:6.

NGSS Lead States. Next generation science standards: for states, by states. The National Academies Press; 2013.

Pobiner B. Accepting, understanding, teaching, and learning (human) evolution: obstacles and opportunities. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2016;159:232–74.

Puhl RM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Austin SB, Suh Y, Wakefield DB. Policy actions to address weight-based bullying and eating disorders in schools: views of teachers and school administrators. J Sch Health. 2016;86:507–15.

Sickel AJ, Friedrichsen P. Examining the evolution education literature with a focus on teachers: major findings, goals for teacher preparation, and directions for future research. Evo Edu Outreach. 2013;6:23.

Troia GA, Graham S. Common core writing and language standards and aligned state assessments: a national survey of teacher beliefs and attitudes. Read Writ. 2016;29:1719–43.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kate Carter and Brad Hoge for advice about the questionnaire content and the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Funding

The funding of the data collection and analysis were provided by the authors’ home institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP was responsible for all fieldwork, data collection and data analysis; contributed to questionnaire content, and collaborated in the writing of the manuscript. GB and AR contributed to questionnaire content and collaborated in the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project involved voluntary participation in a survey. The procedures and recruitment materials were reviewed by the IRB at Penn State University (study # 00011249) and declared exempt.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

2019 Survey of American science teachers: materials and methods

Background

The 2019 Survey of American Science Teachers is the third of a series of three scientific surveys of science teachers. The first, the 2007 National Survey of High School Biology Teachers, was funded by the National Science Foundation and focused on high school biology teachers and their approach to the teaching of evolutionary biology. The second, the 2014–2015 National Survey of American Science Teachers, was conducted by Penn State under with the National Center for Science Education and focused on the teaching of climate change. This second study added a sample of middle school teachers and sampled high school teachers of all four core subjects: earth science, biology, chemistry, and physics. This third study retains a focus on high school biology teachers (from the 2007 survey) and middle school science teachers (from the 2014–2015 survey).

In order to allow valid comparisons to prior surveys, the most recent effort replicated many of the questions and adhered closely to the study design from previous waves. As a result, when examining the data from identical questions, it is possible to compare this wave’s middle school sample to the middle school sample from 2014–2015, and to compare the high school biology sample to the 2007 survey and to the biology subgroup within the 2014–2015 high school sample.

Sampling

The 2019 Survey of American Science Teachers employs two stratified probability samples of science educators. The first represents the population of all science teachers in public middle or junior high schools in the United States. The second represents all biology or life science teachers in public high schools in the United States.

There is no comprehensive list of such educators. However, a direct mail marketing company, Market Data Retrieval (MDR, a division of Dunn and Bradstreet) maintains and updates a database of 3.9 million K–12 educators.

MDR selected probability samples conforming to our specifications. Specifically, MDR first identified eligible schools (public middle and junior high schools, and public high schools) and then selected all middle school teachers with the job title “science teacher” and all high school teachers with the job title “biology teacher” or “life science teacher.”

The middle school universe contained 55,001 teachers with full name, school name and school address. From these, teachers were selected with probability 0.0455 independently from each of 151 strata defined by urbanism (city, suburb, all others) and state, with the District of Columbia being its own stratum. This resulted in a sample of 2511 middle school science teachers.

The high school biology universe contained 30,847 teachers with full name, school name and school address. From these, teachers were selected with probability 0.0810 independently from each of 151 strata defined by urbanism (city, suburb, all others) and state, with the District of Columbia being its own stratum. This resulted in a sample of 2503 middle school science teachers.

Of the 5014 elements in the two samples, MDR provided current email addresses for 4150, or 82.8%.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaires for this survey included questions employed in the 2007 National Survey of High School Biology Teachers (which focused on the teaching of evolution), and the 2014–2015 National Survey of American Science Teachers (which focused on the teaching of climate change). A few new questions were developed to measure teachers’ perceptions of local public opinion.

The survey was initially written for pencil/paper administration and—when finalized—programmed so it could be administered on the Qualtrics online survey platform.

Fieldwork

The survey design was a “push to mail” strategy in which all 5014 respondents received an advance pre-notification letter, a survey packet with incentive ($2 in cash) and a postage paid return envelope, two reminder postcards and a replacement survey packet. Non-respondents for whom we had an email address then received an email invitation to complete the survey online.

This included 3161 non-respondents with emails supplied by MDR, and an additional 352 collected during the non-response audit.

Non-respondents then received two additional email reminders. Field dates are summarized in Table 11.

Non-response audit

Beginning on April 11, 2019 after most paper surveys had been received and logged, we identified a subsample of 700 non-respondents, and launched a detailed non-response audit on this group. The primary goal was to confirm or disconfirm their eligibility. From the time we began the audit of non-respondents, we received questionnaires from 62 of these teachers. They were removed from the audit, leaving 638 audited non-respondents.

For each person, we first searched for their school, and sought to locate a current school staff directory. If no directory was found, we searched all classroom web sites at the school, and searched the school web site for the teacher’s full name and last name. If we found a match for the teacher anywhere on the school web site, that non-respondent was confirmed as eligible.

In some cases, we found a teacher in the same subject and same first name, but with a different last name. If we were able to absolutely confirm that teacher had recently changed names (e.g., their email matched the name in our list) that teacher was confirmed as eligible.

If we did not find the teacher, we did two broader web searches. First, a search with the teacher’s full name and the keyword “science.” In some instances, this brought up results indicating that the teacher had changed jobs or retired (e.g., information on the former teacher’s LinkedIn page). These were confirmed as ineligible. We recorded the following outcomes:

Teacher confirmed as eligible—listed on school website.

Teacher confirmed as eligible—classroom web pages identified.

Teacher confirmed as eligible—other (e.g., listed in recent news story).

Confirmed ineligible—school has current staff directory, and teacher not listed.

Confirmed ineligible—other (e.g., teacher identified as instructing in a different subject).

Unable to determine—school does not have a staff directory.

Unable to determine—school does not have functional web site.

The final results of the audit are summarized in Table 12.

Thus, of all non-respondents (and assuming ¼ of the unknowns are ineligible) we estimate that 72% are eligible. This is the basis for calculating the “e” component in the response rate (American Association for Public Opinion Research 2006).

Dispositions and response rates

Every individual on the initial mailing list of 5014 names and addresses was assigned a disposition code.

A survey was considered complete if the respondent answered questions from at least two of the following three question groups: Question #1, which asked teachers how many class hours they devoted to each of nine topics (appearing on the second page of the paper questionnaire); a group of attitude questions appearing on pages 7–8 of the written questionnaire; and a group of demographic and background variables on pages 9 and 11 of the paper questionnaire.

A survey was considered partially complete if the respondent answered at least how many class hours they devoted to each of nine topics (appearing on the second page of the paper questionnaire).

A summary of the dispositions appears in Table 13.

Response rates

We utilize the response rate definitions published by the American Association for Public Opinion Research. These require an estimate of the percentage of all non-respondents who are eligible or non-eligible (e.g., due to retirement) to complete the survey. This quantity, referred to as e, was estimated from a detailed audit of 638 non-respondents. Based on these dispositions we calculate the response rate (AAPOR response rate formula #4) to be 37%. This is interpreted as the percentage of all eligible respondents who submitted a usable questionnaire (complete or partially complete). Respondents who returned questionnaires that are blank or fail to qualify as partial, are considered non-respondents. The details of the response rate calculation are reported in Table 14.

Response rates by teacher and school characteristics

Response rates can be broken down and estimated for different groups, providing that there are data for non-respondents as well as respondents. As a result, we cannot test for differences based on questionnaire items (we lack information on seniority, degrees earned, religiosity, and so on for all non-respondents).

We can, however, utilize “frame” variables and those provided by the direct mail vendor MDR. Table 15 reports on eight such comparisons.

Teacher characteristics The response rate was somewhat lower for middle school teachers (34%) compared to high school biology teachers (40%). Using the salutations (Mr., Ms., Miss, Ms., etc.) provided in the direct mail file, we classified teachers as female, male, or gender unknown. The latter group included a small number of teachers with salutations of “Dr.” or “Coach.” However, the large majority had gender-ambiguous first names such as Tracy, Jamie, Kim or Chris. Men (39%) and women (38%) did not differ significantly, but we had a lower return among those whose communications could not be personalized (Dear Kim Smith rather than Dear Mr. Smith, for example).Footnote 7

The value of conducting an email follow-up to the pencil/paper survey is evident in the 39% response rate for those teachers with a valid email supplied by the vendor (those lacking an email had a 30% response rate). Note that some of these additional returns were paper surveys returned only after teachers received an email announcing the availability of a web survey.

School type We had a somewhat lower response rate from teachers at public charter schools (31%). Note, however, that because charters still represent a tiny slice of the public school market, raising their response rate to the overall average would have only increased the number of surveys completed by charter school teachers by three or four.

School demographics As in previous surveys we find lower response rates from teachers working in schools with medium or large minority populations. Schools whose student bodies are more than 15% African American or more than 15% Hispanic or more than 50% free lunch eligible all had response rates between 30 and 33%.

Urbanism Finally, response rates did not differ substantially by urbanism except for schools in central cities with populations exceeding 250,000. Teachers in these large school systems responded at a 30% rate.

Overall, we uncovered systematic differences. By and large these are modest in magnitude and do not introduce major distortions in the data. For example, teachers in large central city school systems constituted 12% of the teachers we recruited, and 10% of the final data set. However, since these individual differences might be additive (e.g., central city schools with many minority and school lunch-eligible students) we estimated a propensity model to assess the total impact of all factors simultaneously.

Table 16 reports a logistic regression model in which the dependent variable is the submission of a usable survey (scored 1, all other dispositions scored 0, with confirmed ineligible respondents dropped from the analysis).

This confirms most of the observational difference reported in Table 15. The odds ratio column is more intuitive and shows that the odds of returning a usable survey was 26% higher in the high school sample, 30% higher for teachers with a valid email on file, and about 26% higher when we used a gender-based salutation. Teachers at schools with sizable Black and Hispanic presence in the student body are also under represented (odds rations below 1). However, after controlling for student body composition, the effects of school lunch eligibility and urbanism are diminished.

Propensity scores We use this model to calculate the probability to respond for all original members of the sample. That allows us to calculate the response propensity for all respondents. Those whose characteristics make them unlikely to respond must, therefore, speak on behalf of more non-respondents. We use the inverse of the propensity as a second-stage weighting adjustment.

Weighting

Analysis weights were constructed in a two-stage process. A base weight adjusts for possible under-coverage by the sample supplier and the non-response adjustment balances the sample based on characteristics that are predictive of non-response (e.g., student body composition).

Base weight MDR claims to have contact information for approximately 85% of all K–12 teachers, but that coverage rate can vary by grade, subject, and state.

We assume that biology teachers constitute the same share of high school faculty in each state. It follows that the distribution across states in the MDR database should be proportional to the number of teachers in each state. If not, adjustment is necessary to make the sample fully representative.

We therefore constructed the following ratio:

This was standardized to have a mean of 1.0 so that ratios above 1 indicate relative under-coverage by MDR.

Non-response calibration The second stage weight is based on the logistic regression model reported in Table 16. From this model, we calculated the probability of completing the survey (defined as completing a usable survey, classified as “complete” or “partial” in Table 13).

The second stage non-response adjustment is simply the inverse of the response propensity.

Analysis weight (designated as final_weight in the data set) is the product of the first stage coverage adjustment and the second stage non-response adjustment, standardized so it has a mean of 1. The weights range from 0.39 to 3.15, with a standard deviation of 0.35. Ninety percent of the cases have weights between 0.54 and 1.70, indicating that weighting will have only a small impact on statistical results in comparison to unweighted analyses.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Plutzer, E., Branch, G. & Reid, A. Teaching evolution in U.S. public schools: a continuing challenge. Evo Edu Outreach 13, 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-020-00126-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-020-00126-8