Abstract

Limited empirical investigation has been devoted to understanding the multiple- effect mechanisms of moral leadership, especially the relationship between mediators. Drawing from both social learning and social exchange theories, this study examines whether value congruence and leader-member exchange (LMX) mediate the effect of moral leadership on followers’ positive work behaviors. Using two-wave survey data from 395 Chinese employees, the results indicate that both value congruence and LMX act as mediators in the relationship between moral leadership and positive work behaviors. Furthermore, a sequential mediation link from moral leadership to value congruence, then to LMX, and finally to positive work behaviors was established. Theoretical and practical implications are further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moral and ethical aspects of leadership are becoming an important topic in extant leadership research due to recent shocks stemming from moral scandals in various industries (Bedi et al. 2015; Yukl 2010). Leaders possess hierarchal authority, allocate valuable resources, and set the standard of social norms within organizations (Yukl and Lepsinger 2004). Through processes including social learning and social exchange (Brown and Treviño 2006), employees’ attitudes and behaviors would be profoundly influenced by whether their leaders act with morality. Moral leadership is defined as “leader’s behavior that demonstrates superior personal virtues, self-discipline, and unselfishness” (Cheng et al. 2004, p. 91). When leaders’ behaviors are consistent with the social norm and considered ethical, moral, and righteous, there can be profound positive influence leading to beneficial outcomes. Indeed, empirical investigation has established that moral leadership is positively related to normative commitment (Erben and Güneşer 2008), trust (Lau et al. 2007), psychological empowerment (Li et al. 2012), creativity (Gu et al. 2015), and performance (Chen et al. 2014; Wu 2012). Recently, it was found that moral leadership can elicit followers’ proactive behaviors such as voice (Chan 2014; Zhang et al. 2015) and job crafting (Tuan 2018).

Although extant literature has explored various psychological mechanisms of moral leadership such as perceptions of justice (Li et al. 2012), identification with supervisor (Gu et al. 2015), and trust (Wu 2012), there is limited research that has examined multiple mediators simultaneously, and especially the relationship among mediators (Chen et al. 2014). Furthermore, although leader-member exchange (LMX) is established as an important mediator of moral leadership (Gu et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015), the process by which moral leadership leads to LMX is unclear. Examining multiple mechanisms simultaneously will not only delineate a clearer picture of the effect process, but also clarify the interrelationships and relative importance of different mediators. To this end, the current study examines simultaneously the mediating roles of value congruence and LMX between moral leadership and followers’ positive work behaviors, among a sample of Chinese employees.

By delineating the effect mechanisms of moral leadership on subordinates’ positive work behaviors, the current study makes three important contributions. First, China has come to a stage where employees’ proactivity is critical for organizations to survive and thrive (Grant and Ashford 2008; Liu et al., 2010a, b). In a culture characterized by interpersonal harmony and power distance (Schwartz 1999), employees may choose to remain inactive out of fear of vulnerability or even retaliation (Morrison 2011). Leader morality may ease those concerns and elicit proactive behaviors (Zhang et al. 2015). We contribute to the empirical base of moral leadership by extending the nomological network of moral leadership to employees’ positive work behaviors in a cultural context where proactivity is both critical and considered difficult to elicit (Zhang et al. 2015). Practically, our results provide insights on how to cultivate positive work behaviors and proactive behaviors. Second, we simultaneously test the mediating effects of value congruence and LMX. Moreover, we test whether value congruence could lead to LMX, and thus form a sequential mediation link from moral leadership to value congruence, then to LMX, and finally to positive work behaviors. This examination would shed light on the integration of two important explanations of moral leadership’s effect, namely the social learning and the social exchange processes (Treviño et al. 2000). Furthermore, the relationship between perceived value congruence and LMX is seldom empirically examined. Our investigation of the relationship between value congruence and LMX provides insights on the initiation of social exchange relationship from a similarity perspective (Steiner 1988). Third, morality is “normatively appropriate conduct” (Brown et al. 2005, p. 120), in that social and institutional context is critical to its meaning and effect (Brown and Treviño 2006). Leader morality has long been emphasized in China as an effective means of influence (Farh et al. 2008). There is a growing body of research on leader morality using China as the research setting. This study’s discussion of the nature, process, and effect of moral leadership strives to further explicate the moral leadership concept in China.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

Leader morality has long been recognized as an effective means of influence (Yukl 2010). Moreover, it is normatively appropriate (Treviño et al. 2006) and socially responsible (Zu and Song 2009). As such, leader morality is considered a critical factor within many leadership concepts, including transformational leadership (Burns 1978), servant leadership (Greenleaf 1977), authentic leadership (Avolio and Gardner 2005), and paternalistic leadership (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008). A leader’s personal attributes such as honesty, integrity, unselfishness, justness, and caring are considered important for leader morality in these conceptualizations. However, a theoretical definition and systematic investigation specifically paid to moral leadership is only in its early stage of development (Brown and Mitchell 2010). Recent concerns over organizational scandals and corruption have necessitated paying closer attention to leader morality (Fehr et al. 2015). Responding to this situation, we have witnessed an increase in the social scientific approach to moral leadership research in the past decade (Bedi et al. 2015; Brown and Treviño 2006).

Morality is very important in the Chinese way of leading (Farh et al. 2008). Confucianism leans more towards leader morality than legal institutions (Fei et al. 1992; Xin and Pearce 1996). This tradition is reflected in modern communist doctrine where leader morality is considered very important when selecting and promoting political officials (Miao et al. 2014). Accordingly, it is expected that an effective Chinese leader should be acting in a moral manner (Farh and Cheng 2000). This phenomenon is reflected in many leadership theories rooted in the Chinese culture. For example, one of the three dimensions of paternalistic leadership is morality (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008). Additionally, it was found that the performance-maintenance leadership theory should include another factor in China, namely moral character (Ling and Chen 1987). From an indigenous perspective, Li and Shi (2005) developed a Chinese transformational leadership scale and found that one of the four dimensions is moral modeling. This conceptualization of leader morality involves personal attributes such as being honest, fair, and trustworthy, and having integrity; scarifying personal interest for the organization; putting subordinates’ interests before their own; working together with subordinates; setting an example by working hard; not taking credit for others’ work; sharing weal and woe with subordinates; not deliberately giving subordinates a difficult time, and not retaliating against subordinates through the abuse of power. We adopt this conceptualization of moral leadership in this study for three reasons. First, this indigenous scale captures a broad range of moral characteristics in the Chinese work context and was proved to have good psychometrical properties (Li et al. 2015; Liu et al., 2010a, b). Second, it does not contain a moral management element. Some have cautioned against the moral management element of ethical leadership in China by claiming that “punishment by ethical leadership might lead followers to be dissatisfied” (Liu et al. 2013, p. 579). Third, moral leadership is usually treated as a sub-dimension of paternalistic leadership in studies conducted in China (Chen et al. 2014; Gu et al. 2015). Our conceptualization complements this approach by taking a different perspective.

Moral leadership and followers’ positive work behaviors

Employee proactivity has attacted increasing research attention due to environmental uncertainty having rendered organizations more reliant on employees’ initiatives (Crant 2000). Proactive behaviors are discretionary extra-role behaviors not specifically required by the job and may not be rewarded in any form. These behaviors are beneficial to organizations but are risky to the individuals. Proactivity means challenging the status quo. This could be perceived as creating more work or even causing trouble. Out of safety concerns such as avoiding a supervisor’s retaliation, individuals may choose to remain inactive or silent instead of taking initiatives (Morrison 2011). In this study, we focus on positive work behaviors as a form of proactivity. This includes proactive behaviors such as conducting more work than required, working overtime, making attempts to change working conditions, negotiating with supervisors to improve the job and trying to think of ways to improve the job (Lehman and Simpson 1992). Lehman and Simpson (1992) introduced the ELVN model to describe employees’ response to job dissatisfaction: Exit means leaving the organization; Neglect means using psychological withdrawal behaviors such as absenteeism or sabotage to detach oneself; Loyalty means passively waiting for problems to solve themselves; and Voice means proactively providing constructive ideas and work efforts to help the organization. Among these four choices, Voice is most constructive and was operationalized as a positive work behavior by Lehman and Simpson. Positive work behaviors include not only expressing constructive opinions, but also solid work behaviors that could change work processes and contexts. Because it was claimed that moral leadership’s effect on proactivity should include not only expressing opinions, but also behaviors (Walumbwa et al. 2011; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009), our choice of positive work behaviors as outcome would extend the nomological network of moral leadership.

Leadership has been found to be effective in eliciting subordinates’ proactivity (Wu and Parker 2017). Within our context, some theoretical rationales suggest moral leadership should lead to followers’ positive work behaviors. First, moral leaders encourage followers to speak up and value followers’ inputs (Brown et al. 2005). This open attitude can encourage followers’ initiatives (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2012). Second, moral leaders are principled decision makers who act in an ethical, honest, and trustworthy manner that emphasizes a fair and just work environment. Fair, honest, and respectful treatment from the supervisor is related to proactivity because followers are less concerned (Janssen and Gao 2015). Psychological safety is an important antecedent of initiative (Liang, Farh, and Farh 2012). A just and equitable work environment would result in less psychological withdrawal. Third, moral leaders are seen by followers as legitimate and creditable role models. The followers would directly or vicariously learn from moral leaders to take initiatives because they would observe their leaders openly expressing ideas and changing the work environment. This learning effect would be especially significant when the issue is morality related, because moral leaders can elevate followers’ moral reasoning and make those positive work behaviors self-concordant (Dukerich et al. 1990). Furthermore, modeling moral leaders makes it possible for followers to internalize the values and ideologies proposed by leaders, and thus to be socialized as organizational insiders (Yang 2014). This identification would also bring positive work behaviors because followers would see organizational goals and personal interests as congruent (Wang and Kim 2013). Fourth, moral leadership would develop a quality relationship with followers characterized by mutual trust, liking, and long-term mutual obligation. This social exchange relationship would lead followers to reciprocate by displaying positive work behaviors. In this sense, moral leadership is related to trust (Chen et al. 2014), and the more followers trust their supervisor, the more initiatives there will be (Hsiung 2012). Empirical evidence supports these assertions. It was found that moral leadership is positively related to voice (Chan 2014; Zhang et al. 2015), job crafting (Tuan 2018), and citizenship behavior (Chen et al. 2014). Based on the above rationale, we make the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Moral leadership is positively related to followers’ positive work behaviors.

The mediating role of value congruence

Moral leadership is proposed as a value-based approach that assimilates followers’ values, but empirical evidence directly relating moral leadership to value congruence is scant. Value congruence is the similarity of values between the organization and the employees (Edwards and Cable 2009). Because value congruence can lead to beneficial outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, trust, and better performance (Hoffman and Woehr 2006; Verquer et al. 2003), examining its antecedent is very important. Value-based leadership practices such as transformational leadership are established as socialization factors that induce followers to learn from their leaders and result in value congruence (Hoffman et al. 2011). We propose that moral leadership induces value assimilation based on the social learning process as well (Bandura 1977; Davis and Luthans 1980). Social learning theory claims that individuals would learn the appropriate way of conduct in the social environment by observing a role model’s behaviors and the related outcomes of those behaviors (Bandura 1977). This learning would subsequently result in the internalization of leaders’ values. Moral leaders are treated as legitimate and credible role models (Brown et al. 2005). Supervisors set the tone of communication within work groups, allocate important resources and have power over important work-related decisions. They are treated as representatives of the organization (Whitener et al. 1998). Hence, a supervisor is an important source from whom to deduct social norms. Followers directly emulate the attitudes and behaviors of their supervisor, and also vicariously learn by observing the behaviors and related outcomes of their colleagues. Because outcomes are decided by supervisors as well, this vicarious learning process can also be attributed to the supervisors’ attitudes and behaviors. This direct and vicarious learning by followers would result in a socialization process whereby followers learn from their supervisors’ words and deeds. Because these words and deeds reflect the values they hold, if the supervisors behave in a moral way, followers would be influenced to the extent that these values are assimilated; that is, the institutionalization of ethics would occur (Jose and Thibodeaux 1999). We suspect moral leadership would be more effective on assimilating values than other value-based leadership concepts such as transformational leadership or servant leadership. Although transformational leadership is value-based, it also contains other dimensions such as using charisma and individualized considerations (Bass and Riggio 2006). Additionally, servant leaders’ display of values by serving subordinates might be indirect and difficult to be understood (Graham 1991). For example, it was found in a recent study that servant leadership mainly had its effect on engagement through social exchange rather than the social learning mechanism (Bao, Li, and Zhao 2018). We think because moral leadership principally uses values as the way of influencing subordinates, its effects on the assimilation of values would be more profound. Indeed, the instillation of values from the role modeling of a supervisor is considered an important process whereby the organizational culture is socialized to the followers (Schein 1985).

When personal values and organizational values are congruent, individuals would prioritize the organizational goal as their own, and thus helping the organization would be consistent with their personal interests. According to the self-concordant motivational theory (Bono and Judge 2003), followers of value-based leaders would regulate their goal-directed efforts toward what the leader’s values emphasize. In our case, we propose that value congruence would lead to positive work behaviors. When individuals internalize organizational values, they tend to develop identification with the organization and have a sense of oneness with and belongingness to the organization (Riketta 2005). Displaying positive work behaviors would protect not only what they personally value, but also what they consider important to their personal categorization in the society. In this vein, it was found that value congruence is related to proactive behaviors such as voice (Wang et al. 2012) and citizenship behavior (Hoffman and Woehr 2006; Kristof 1996). Based on this reasoning, we hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Value congruence mediates the relationship between moral leadership and positive work behaviors.

The mediating role of leader-member exchange

Social exchange has been used to explain the effect of moral leadership (Brown and Treviño 2006; Brown et al. 2005). It is believed that a supervisor and a follower would develop an exchange relationship based on the quality of former interactions (Blau 1964). Exchange relationship is characterized by a continuum with economic and social exchanges at both ends. Economic exchange is characterized by short-term expectation that is constrained within specific transactions while social exchange is characterized by long-term expectations, generalized orientation, and further develops into mutual respect, trust, and liking. “Social exchange comprises actions contingent on the rewarding reactions of others, which over time provide for mutually and rewarding transactions and relationships” (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005, p. 890), and is critical to understanding discretionary behaviors such as positive work behaviors (Blau 1964). We use LMX as a proxy of social exchange in this study because it represents the overall quality of the social exchange process between leaders and subordinates, and is the most commonly used concept to represent the social exchange relationship between leader and subordinates (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995). Moral leadership would bring high quality social exchange, LMX in our case, because when followers receive care, consideration, support, and help from their moral leaders, they feel valued, respected, and in debt. These favorable treatments from the supervisor would be considered as signals to develop a long term relationship. Followers would then show positive attitudes and behaviors to reciprocate the considerate treatment. Accordingly, followers would try to reciprocate the care and consideration by being proactive because they would consider those positive work behaviors as currencies to reciprocate the favorable treatment received (Erdogan and Liden 2002). Following the social exchange perspective, affective trust has been established as a mediator between moral leadership and both in-role performance and citizenship behavior (Chen et al. 2014). There is also some initial evidence that has established LMX as a mediator of moral leadership’s effect (Gu et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015). Furthermore, in line with social exchange theory, LMX was found to be positively related to proactivity in previous studies (van Dyne et al. 2008). Based on these theoretical arguments and empirical evidence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Leader-member exchange mediates the relationship between moral leadership and positive work behaviors.

The sequential mediating role of value congruence and leader-member exchange

Although multiple psychological mechanisms underlying moral leadership’s effect have been proposed and tested (Brown and Treviño 2006), there are still some limitations. Researchers usually used idiosyncratic mediators suited to their specific dependent variables without simultaneously testing different mediators in a theoretically coherent manner. Furthermore, the process through which moral leadership initiates social exchange with subordinates is not clear. In order to fill this gap, we test the sequential mediating role of value congruence and LMX.

The relationship between value congruence and LMX is complicated. For example, LMX was found to moderate the relationship between value congruence and career satisfaction in that value congruence is only related to career satisfaction when LMX is low (Erdogan et al. 2004). However, another study suggested value congruence was related to outcome when LMX was high (Kim et al. 2013). We propose value congruence will induce a better social exchange relationship. Although the development of LMX is still an under-specified domain, there is some evidence suggesting that value congruence is a possible antecedent. First, similarity leads to people’s propensity to exchange with each other (Steiner 1988). For example, conscientiousness similarity (Deluga 1998) and proactive personality congruence (Zhang et al. 2012) were related to LMX because those similarities might ease the concern related with initial developments of social exchange. Perceived differences between supervisor and follower was negatively related to LMX (Bernerth et al. 2008). As a type of deep-level similarity, value congruence can be another inducement to followers’ propensity to engage in LMX. Second, value congruence would bring positive psychosocial and relational states such as elevated trust, reduced risk, mutual liking, ease of communication, and improved predictability (Edwards and Cable 2009). These states are “social glue” that would smooth the development of the exchange relationship. For example, Ashkanasy and O’Connor suggested that value congruence could lead to LMX (1997). Third, if we deem value congruence as a form of psychological need that individuals seek from a working situation (Edwards and Cable 2009), then the perceived fulfillment of value need is a form of exchange relationship itself. In a recent study, it was found out that the more a leader fulfills followers’ work values, the higher LMX will be developed (Marstand et al. 2017). Based on the above considerations, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4: Value congruence and leader-member exchange sequentially mediates the relationship between moral leadership and positive work behaviors.

Method

Participants and procedures

A two-wave online survey was used to collect data from Chinese employees working in various industries. Eighty part-time master students enrolled on a management degree program in a university in Beijing were asked to invite 10 of their colleagues from different departments to participate. We used email to provide links to the survey. We assured anonymity, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of the survey. To improve the response rate, 30 Chinese yuan was provided as an incentive. We asked the respondents to report their direct supervisor’s moral leadership in the first round of the survey, together with respondents’ demographics. Perceived value congruence with the organization, LMX, and positive work behaviors were measured in the second round. 588 of the 800 contacted employees responded in the first round, while 425 of them responded again in the second round, yielding a final response rate of the 53%. We used 395 responses due to missing data. Among the 395 respondents, 207 (52.4%) are female and the average age is 32.46 years (SD = 6.38). In terms of education level, 40 have a junior college degree (10.1%), 230 have a bachelor’s degree (58.2%), 113 have a master’s degree (28.6%), and 12 have received their doctorate degree (3%). The average tenure with their direct supervisor is 2.69 years (SD = 3.03).

Measures

Moral leadership

Eight items were used to measure moral leadership using the moral modeling dimension of Li and Shi’s transformational leadership scale (2005). A sample item is “My supervisor will not take credit for other people’s work.” Responses were made on a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from 1, representing “strongly disagree,” to 5, representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Value congruence

Value congruence was measured using the 3-item perceived person-organization fit scale (Cable and DeRue 2002). A sample item is “The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values.” Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-scale ranging from 1, representing “strongly disagree,” to 7, representing “strongly agree.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

LMX

LMX was measured using seven items from Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995). A sample item is “My supervisor recognizes my potential very well.” Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-scale. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Positive work behaviors

We used five items to measure the positive work behaviors of followers (Lehman and Simpson 1992). The items are: “I did more work than required” “I volunteered to work overtime” “I made attempts to change work conditions” “I negotiated with supervisors to improve job” and “I tried to think of ways to do job better.” Responses were made on a 5-point Likert-scale. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Controls

We collected demographic information of followers to use as control variables. Respondents’ gender (0 = female, 1 = male), age (in years), educational level (1 = Junior college, 2 = Bachelor’s, 3 = Master’s, 4 = Doctorate), and dyadic tenure with supervisor (in years) were included.

Results

Measurement model and descriptive statistics

Prior to hypotheses testing, we performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to establish discriminant and convergent validity. As shown in Table 1, theorized four-factor model (moral leadership, value congruence, LMX, and positive work behaviors) fit the data well (χ2[224] = 662.47, χ2/df = 2.96, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93) (Hu and Bentler 1999). In addition, the factor loadings of the items are all greater than 0.50 (ranging from 0.52 to 0.95) and significant at 0.001 level.

Next, we compared this measurement model with five alternative models that may be theoretically or empirically plausible. Chi-square difference test reveals that the four-factor model is a better fit (Models a–e, Table 1). We also computed composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and maximum shared variance (MSV) (Hair 2010). As shown in Table 2, the CR scores are all above 0.7 (ranging from 0.88 to 0.96), and the AVE scores are all above 0.5 (ranging from 0.52 to 0.83). Also, the MSV values are smaller than AVE values for the respective variables. Furthermore, the square root of AVE is greater than inter-construct correlations (Fornell and Larcker 1981). These results suggest that our studied variables have clear convergent and discriminant validity, and we continued to examine these variables as distinct constructs.

The means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations are reported in Table 2. Moral leadership is positively related to positive work behaviors (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), value congruence (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), and LMX (r = 0.54, p < 0.01). Value congruence is positively related to LMX (r = 0.55, p < 0.01), and positive work behaviors (r = 0.48, p < 0.01), while LMX is positively related to positive work behaviors (r = 0.52, p < 0.01). These correlations provide preliminary support for our hypotheses. As can be seen from Table 2, only age is significantly related to positive work behaviors (r = 0.12, p < 0.05). After a series of model comparisons, we reported below only the results of controlling age on positive work behaviors, while not including other control variables (Becker 2005). The results are identical with and without the other controls.

Test of hypotheses

Hypothesized relationships were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). To test for mediation, we used the bias-corrected (BC) bootstrapping procedures to estimate the size of indirect effects and their confidence intervals. This test is claimed to have higher power, controls Type I error better, and does not rely on normal distributions (MacKinnon 2008; Preacher and Hayes 2008).

As indicated in Table 1, our hypothesized model fits the data well (χ2[246] = 695.02, χ2/df = 2.82, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93). We compared this hypothesized model with two alternative models. In alternative model 1, we added a direct path from moral leadership to positive work behaviors. Our mediation hypothesis would be further supported if this alternative model did not improve the fit. The fit indices of this alternative model are almost identical (χ2[245] = 694.71, χ2/df = 2.84, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93). The Chi-square difference test reveals that the two models are not significantly different. The path from moral leadership to positive work behaviors is also insignificant (γ = 0.03, p = 0.58). In alternative model 2, we deleted the path from value congruence to LMX from the hypothesized model. As shown in Table 2, this model is significantly worse than the hypothesized model based on the Chi-square difference test (χ2[247] = 751.40, χ2/df = 3.04, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.08, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92). These comparisons provide us with confidence that the hypothesized sequential mediation model is more plausible than a partial mediation model or a parallel mediation model.

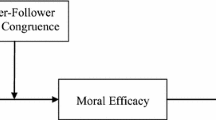

Table 3 presents the estimate of total and indirect effects. As can be seen, the total effect and all three indirect effects are significant. Specifically, supporting hypothesis 1, moral leadership is positively related to positive work behaviors (γ = 0.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.24]). Additionally, value congruence mediates the effects of moral leadership on positive work behaviors (γ = 0.07, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.11]), and LMX also mediates the effects of moral leadership on positive work behaviors (γ = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.14]). These results support hypotheses 2 and 3. Furthermore, supporting hypothesis 4, value congruence and LMX sequentially mediate the effect of moral leadership on positive work behaviors (γ = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.06]). Standardized coefficient estimates associated with our hypothesized model are presented in Fig. 1.

Discussion

We examined whether moral leadership can lead to followers’ positive work behaviors and whether this relationship is simultaneously mediated by value congruence and LMX. Furthermore, we tested whether there is a sequential mediating link from moral leadership to value congruence, then to LMX, and finally to positive work behaviors. The proposed hypotheses were supported by our two-wave data collected from Chinese employees. Our study provides important implications for both leadership research and practice in China and beyond.

Theoretical implications

Following a line of research that emphasizes the effect of leadership on employees’ proactivity, we reconfirmed that a Chinese leader’s morality is related to followers’ positive work behaviors—an important proactivity outcome that includes changing work processes and contexts. This finding is particularly important because China is characterized by interpersonal harmony (Schwartz 1999; Wang and Juslin 2009) and power distance (Hofstede 2001). We found that in a social context where interpersonal conflict is avoided and power distance is emphasized, a “socially appropriate” way of leading in which moral and ethical aspects are emphasized would bring proactivity. This study extends the nomological network of moral leadership research in China by introducing a new outcome variable. China has come to a stage where employees’ initiatives would be critical for its next wave of development. Some have expressed the concern that certain traditional Chinese values would be harmful to employees’ proactivity (Wang and Kim 2013). Our study eases this concern by proving that moral leadership would be a powerful way to boost proactivity. Future studies are needed to further verify the effects of interpersonal harmony and power distance on our reported relationship. For example, do moral leaders in higher positions affect employee proactivity differently than moral leaders positioned at lower organizational levels?

Following a social learning perspective, we found value congruence acts as a mediator between moral leadership and positive work behaviors. This result supports the value assimilation function of moral leadership, a function long claimed but seldom tested (Tang et al. 2015). Future work is needed to examine how moral leadership can actually change followers’ values, especially those values that are related to moral functions. A recent study conducted in South Korea, also a traditional Confucian society, found that ethical leadership was related to followers’ moral efficacy only under high leader-follower value congruence (Lee et al. 2017), suggesting a more complicated relationship between leader morality and value congruence. It could be that different types of values are at play when individuals are under the influence of a moral leader. We measured perceived value congruence with the organization in this study without referring to specific value contents. Future studies can use commensurate scales to tackle specific values (Edwards and Cable 2009; Meglino and Ravlin 1998). It is also possible that different subordinates would respond to moral leaders differently. For example, behavioral plastic theory suggests that people would respond differently to leader’s influence (Brockner et al. 1988). Future studies can investigate possible individual differences that could moderate the value-assimilating function of moral leadership. For example, it is worthwhile to investigate the moderating role of individual traditionality on the effectiveness of moral leadership (Farh et al. 2007).

Echoing previous works (Gu et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015), we reaffirmed LMX as a mediator of moral leadership’s effect. This result proves that using a social exchange perspective to understand the mechanism of moral leadership is an appropriate approach. However, according to the multi-foci exchange perspective (Cropanzano et al. 2002; Lavelle et al. 2007), individuals would develop different exchange relationships with different constituents of their environment. In this study, we see a moral leader as the representation of the organization, such that followers direct their reciprocal efforts toward the organization. It could be possible that the effect of moral leadership “remain[s] at the interpersonal level” (Chen et al. 2014, p. 800), in that the reciprocal efforts are towards the leader, but not the organization. Future studies need to investigate this multi-foci exchange process involved in moral leadership’s effect (Hansen 2012). Similarly, some claim that moral leaders’ goals would not be limited to the organizational goals (Brown et al. 2005). It would be interesting to examine the possible situation in which subordinates would try to benefit the society at the cost of the organization.

The sequential mediating process we found provides a delineated picture on the effect process of moral leadership by investigating the interrelationships between mediators. Future studies could use other variables representing social learning and social exchange processes, and further investigate their interrelationships in a constructive replication approach (Lykken 1968). The social learning and social exchange processes are seen as complementary and parallel in the Western theory of ethical leadership (Brown et al. 2005). In China, it might be hard to punish followers based on morality because of the emphasis on interpersonal harmony. Thus, leader morality might work mainly from the modeling process. We deliberately chose not to equalize ethical leadership with moral leadership in the current study because we thought there might be some important differences between these two concepts. Ethical leadership is “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005, p. 120). Simultaneously using role modelling and rewards and punishment based on values and morality is considered a critical difference between ethical leadership and other value-based leadership concepts (Brown and Treviño 2006). However, we did not think moral leadership necessarily include punishments based on morality. In fact, in Zheng and colleagues’ Chinese ethical leadership scale, only one from the 13 items was related to the transactional aspect (Zheng et al. 2011). When Brown and Treviño (2006) were discussing the cultural boundary of ethical leadership, they also pointed out that there might be differences over the importance attributed to transactional elements of ethical leadership. Similarly, Liu and colleagues cautioned that “punishment by ethical leadership might lead followers to be dissatisfied” in China (Liu et al. 2013, p. 579), which questioned whether ethical leadership in China actually contains a transactional aspect. Moral management/reinforcements might not be an element for Chinese moral leadership. Our study found that a moral leader would assimilate followers’ values and then build a base to initiate a high-quality exchange relationship. Thus, the exchange relationship between followers and moral leaders might be more complicated in China. Future studies should further explore the nature of moral leadership in the Chinese context. We found previous studies concerning moral leadership in China did not focus on using negative reinforcements. This was the reason why we chose to focus on moral leadership instead of the ethical leadership concept that was developed in the Western culture. Future studies should investigate the different effects of positive and negative reinforcements in different cultural contexts to better understand the nature and variations of moral leadership across contexts.

Our work also echoes the work on development of LMX from a similarity perspective (Steiner 1988). Followers’ perceived similarity of values leads to a propensity to engage in a high-quality exchange relationship with the supervisor. Value congruence is treated as “social glue” that lubricates the interaction and aids the development of a better exchange relationship. More studies are needed to explore the effects of similarity on the propensity to engage in social exchange, from both the willingness of the follower and the supervisor. Longitudinal studies are also needed to explore the antecedents of LMX from surface- and deep-level similarity perspectives (Harrison et al. 2002).

Practical implications

Our results support the idea that a socially appropriate way of leading eases the concern inherent within positive work behaviors. Moral leaders are seen as role models and help to develop a high-quality social exchange relationship with followers which then leads to proactivity. This is especially important in a context like China where proactivity is considered difficult due to the emphasis on interpersonal harmony and power distance. Thus, our work indicates that selecting leaders based on moral quality and training them under moral reasoning and sensitivity (Treviño 1992) are important ways to strengthen proactivity in the Chinese context.

Perceived value congruence with the organization leads to better exchange and elevated proactivity. These results suggest the importance of value-based screening and socialization processes. Also, it is important for organizations to explicitly state the similarity of values within the work context because the perceived reality rather than the reality itself would influence employees (Lewin 1951). Maybe in the area of environmental uncertainty, we should be relying more on the organizational culture management systems that emphasize similarity and morality simultaneously in order to boost proactivity and creativity (O’Reilly and Chatman 1996).

Limitations

Like any study, our work is subject to limitations. First, although we applied a two-wave design to separate the independent variable from the mediating and outcome variables, causality cannot be assured. Future studies could use experiments or longitudinal design to further investigate the causal nature among studied variables. Second, our sampling method may have affected the generalizability to other contexts. Future work is needed to further investigate these relationships in other culture contexts. Third, our variables were collected from the same source, so although our two-wave design and confirmatory factor analysis eased the concern of common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003), we suggest future work to collect data from difference sources. For example, measuring a supervisor’s perceived proactivity using dyadic data would be more informative. Also, we used perceived value congruence because perceived measure was found to be a better predictor than indirect measure of value congruence (Kristof 1996). Future studies might want to measure value congruence using other approaches such as difference score. Fourth, we used the moral modeling dimension of established transformational leadership scale to measure moral leadership. Future studies should develop an indigenous scale of moral leadership in the Confucian culture. Also, our measurement of value congruence is based on the perceived similarity of values between followers and the organization, but not the similarity of values between followers and the supervisor. The inherent assumption in this treatment is that supervisors are regarded as the representatives of the organization such that followers see supervisors’ values as organizational values. This assumption needs to be further validated because followers may differentiate supervisors from the organization by developing a multi-foci exchange relationship such that reciprocating with the supervisor might be perceived differently from reciprocating with the organization (Hansen 2012; Hansen et al. 2013). Future studies can differentiate between value congruence with the supervisor and value congruence with the organization. Also, the perception of leaders’ morality might be influenced by demographics of the leaders. For example, would female and male leaders’ morality be perceived differently by their followers? Future studies should consider leaders’ demographics when examining moral leadership’s effects.

Conclusion

We found that moral leadership is positively related to followers’ positive work behaviors among a sample of Chinese employees. This relationship is mediated by perceived value congruence with the organization and LMX. Our work reaffirms the effect of value-based leadership on employee proactivity, even in a culture that emphasizes interpersonal harmony and power distance.

References

Ashkanasy, N. M., & O’Connor, C. (1997). Value congruence in leader–member exchange. Journal of Social Psychology, 137(5), 647–662.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bao, Y., Li, C., & Zhao, H. (2018). Servant leadership and engagement: A dual mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 33(6), 406–417.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods, 8(3), 274–289.

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2015). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 1–20.

Bernerth, J. B., Armenakis, A. A., Feild, H. S., Giles, W. F., & Walker, J. H. (2008). The influence of personality differences between subordinates and supervisors on perceptions of LMX. Group & Organization Management, 33(2), 216–240.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: J. Wiley.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 554–571.

Brockner, J., Grover, S. L., & Blonder, M. D. (1988). Predictors of survivors’ job involvement following layoffs: A field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(3), 436–442.

Brown, M. E., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(4), 583–616.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper and Row.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884.

Chan, S. C. (2014). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Human Relations, 67(6), 667–693.

Chen, X.-P., Eberly, M. B., Chiang, T.-J., Farh, J.-L., & Cheng, B.-S. (2014). Affective trust in Chinese leaders: Linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. Journal of Management, 40(3), 796–819.

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7(1), 89–117.

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Cropanzano, R., Prehar, C. A., & Chen, P. Y. (2002). Using social exchange theory to distinguish procedural from interactional justice. Group & Organization Management, 27(3), 324–351.

Davis, T. R. V., & Luthans, F. (1980). A social learning approach to organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 5(2), 281–290.

Deluga, R. J. (1998). Leader-member exchange quality and effectiveness ratings: The role of subordinate-supervisor conscientiousness similarity. Group & Organization Management, 23(2), 189–216.

Dukerich, J. M., Nichols, M. L., Elm, D. R., & Vollrath, D. A. (1990). Moral reasoning in groups: Leaders make a difference. Human Relations, 43(5), 473–493.

Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 654–677.

Erben, G. S., & Güneşer, A. B. (2008). The relationship between paternalistic leadership and organizational commitment: Investigating the role of climate regarding ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 955–968.

Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2004). Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: The compensatory roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 57(2), 305–332.

Erdogan, B., & Liden, R. C. (2002). Social exchanges in the workplace: A review of recent developments and future research directions in leader–member exchange theory. Leadership, 65–114.

Farh, J.-L., & Cheng, B.-S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. Management and organizations in the Chinese context: 84–127, springer.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729.

Farh, L. J., Liang, J., Chou, L.-F., & Cheng, B.-S. (2008). Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: Research progress and future research direction. In C. C. Chen & Y. T. Lee (Eds.), Business leadership in China: Philosophies, theories, and practices (pp. 171–205). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fehr, R., Kai, C. Y., & Dang, C. (2015). Moralized leadership: The construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Academy of Management Review, 40(2), 182–209.

Fei, X., Hamilton, G. G., & Wang, Z. (1992). From the soil, the foundations of Chinese society: A translation of Fei Xiaotong’s Xiangtu Zhongguo, with an introduction and epilogue. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi–level multi–domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

Graham, J. W. (1991). Servant-leadership in organizations: Inspirational and moral. Leadership Quarterly, 2(2), 105–119.

Grant, A. M., & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28(28), 3–34.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York, NY: Paulist Press.

Gu, Q., Tang, L. P., & Jiang, W. (2015). Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader-member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 513–529.

Hair, J. F. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Hansen, S. D. (2012). Ethical leadership: A multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of Business Inquiry, 10(1), 41–58.

Hansen, S. D., Alge, B. J., Brown, M. E., Jackson, C. L., & Dunford, B. B. (2013). Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(3), 435–450.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., Gavin, J. H., & Florey, A. T. (2002). Time, teams, and task performance: Changing effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on group functioning. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 1029–1045.

Hoffman, B. J., Bynum, B. H., Piccolo, R. F., & Sutton, A. W. (2011). Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 779–796.

Hoffman, B. J., & Woehr, D. J. (2006). A quantitative review of the relationship between person-organization fit and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 389–399.

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hsiung, H.-H. (2012). Authentic leadership and employee voice behavior: A multi-level psychological process. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 349–361.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1854–1872.

Jose, A., & Thibodeaux, M. S. (1999). Institutionalization of ethics: The perspective of managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 22(2), 133–143.

Kim, T.-Y., Aryee, S., Loi, R., & Kim, S.-P. (2013). Person-organization fit and employee outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(19), 3719–3737.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49(1), 1–49.

Lau, D. C., Liu, J., & Fu, P. P. (2007). Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(3), 321–340.

Lavelle, J. J., Rupp, D. E., & Brockner, J. (2007). Taking a multifoci approach to the study of justice, social exchange, and citizenship behavior: The target similarity model. Journal of Management, 33(6), 841–866.

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57.

Lehman, W. E., & Simpson, D. D. (1992). Employee substance use and on-the-job behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(3), 309–321.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. New York: Harper.

Li, C., & Shi, K. (2005). Strcuture and measurement of transformational leadership in China. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 37(6), 650–657.

Li, C., Wu, K., Johnson, D. E., & Wu, M. (2012). Moral leadership and psychological empowerment in China. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(1), 90–108.

Li, C., Zhao, H., & Begley, T. M. (2015). Transformational leadership dimensions and employee creativity in China: A cross-level analysis. Journal of Business Research, 68(6), 1149–1156.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J.-L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two–wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92.

Ling, W., & Chen, L. (1987). Construction of CPM scale for leadership behavior assessment. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 19(02), 89–97.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Fu, P. P., & Mao, Y. (2013). Ethical leadership and job performance in China: The roles of workplace friendships and traditionality. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 564–584.

Liu, J., Siu, O. L., & Shi, K. (2010a). Transformational leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of trust in the leader and self-efficacy. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 59(3), 454–479.

Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010b). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202.

Lykken, D. T. (1968). Statistical significance in psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 70(3), 151–159.

MacKinnon, D. (2018). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Routledge.

Marstand, A. F., Martin, R., & Epitropaki, O. (2017). Complementary person–supervisor fit: An investigation of supplies-values (S-V) fit, leader-member exchange (LMX) and work outcomes. Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 418–437.

Meglino, B. M., & Ravlin, E. C. (1998). Individual values in organizations: Concepts, controversies, and research. Journal of Management, 24(3), 351–389.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G., & Xu, L. (2014). Servant leadership, trust, and the organizational commitment of public sector employees in China. Public Administration, 92(3), 727–743.

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412.

O'Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. A. (1996). Culture as social control: Corporations, cults, and commitment. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, Vol. 18, 157–200. Greenwich, Connecticut: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34(3), 566–593.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(2), 358–384.

Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48(1), 23–47.

Steiner, D. D. (1988). Value perceptions in leader-member exchange. The Journal of Social Psychology, 128(5), 611–618.

Tang, G. Y., Cai, Z. Y., Liu, Z. Q., Hong, Z., Xin, Y., & Ji, L. (2015). The importance of ethical leadership in employees’ value congruence and turnover. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 56(4), 397–410.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2012). Ask and you shall hear (but not always): Examining the relationship between manager consultation and employee voice. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 251–282.

Treviño, L. K. (1992). Moral reasoning and business ethics: Implications for research, education, and management. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5), 445–459.

Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128–142.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(32), 951–990.

Tuan, L. T. (2018). Behind the influence of job crafting on citizen value co-creation with the public organization: Joint effects of paternalistic leadership and public service motivation. Public Management Review, 1–29.

van Dyne, L., Kamdar, D., & Joireman, J. (2008). In-role perceptions buffer the negative impact of low LMX on helping and enhance the positive impact of high LMX on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1195–1207.

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., & Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between person-organization fit and work attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 473–489.

Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 115(2), 204–213.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1275–1286.

Wang, A. C., Hsieh, H. H., Tsai, C. Y., & Cheng, B. S. (2012). Does value congruence lead to voice? Cooperative voice and cooperative silence under team and differentiated transformational leadership. Management & Organization Review, 8(2), 341–370.

Wang, J., & Kim, T. Y. (2013). Proactive socialization behavior in China: The mediating role of perceived insider status and the moderating role of supervisors’ traditionality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 389–406.

Wang, L., & Juslin, H. (2009). The impact of Chinese culture on corporate social responsibility: The harmony approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 433–451.

Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M. (1998). Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 513–530.

Wu, C. H., & Parker, S. K. (2017). The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior: A perspective from attachment theory. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1025–1049.

Wu, M. (2012). Moral leadership and work performance: Testing the mediating and interaction effects in China. Chinese Management Studies, 6(2), 284–299.

Xin, K. R., & Pearce, J. L. (1996). Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of Management Journal, 39(6), 1641–1658.

Yang, M. X. (2014). Ethical leadership, organizational identification and employee voice: Examining moderated mediation process in the Chinese insurance industry. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(2), 231–248.

Yukl, G., & Lepsinger, R. (2004). Flexible leadership: Creating value by balancing multiple challenges and choices. San Francisco: Wiley.

Yukl, G. A. (2010). Leadership in organizations (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zhang, Y., Huai, M. Y., & Xie, Y. H. (2015). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. Leadership Quarterly, 26(1), 25–36.

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., & Shi, J. Q. (2012). Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Social Science Electronic Publishing, 55(1), 111–130.

Zheng, X., Zhu, W., Yu, H., Zhang, X., & Zhang, L. (2011). Ethical leadership in Chinese organizations: Developing a scale. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 5(2), 179–198.

Zu, L., & Song, L. (2009). Determinants of managerial values on corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(S1), 105–117.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 71772171 and 71372159) and the project of “985” in China.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the author for data requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author designed the study together with the second author. Data collection and analysis were done by the authors together. The first author drafted the initial manuscript, and the two authors made several rounds of revision together. Both authors read and approved the the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, Y., Li, C. From moral leadership to positive work behaviors: the mediating roles of value congruence and leader-member exchange. Front. Bus. Res. China 13, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-019-0052-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-019-0052-3