Abstract

Background

This study aimed to determine the possible prognostic factors correlated with the treatment modalities of tubo-ovarian abscesses (TOAs) and thus to assess whether the need for surgery was predictable at the time of initial admission.

Materials and methods

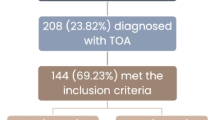

Between January 2012 and December 2019, patients who were hospitalized with a TOA in our clinic were retrospectively recruited. The age of the patients, clinical and sonographic presentation, pelvic inflammatory risk factors, antibiotic therapy, applied surgical treatment, laboratory infection parameters, and length of hospital stay were recorded.

Results

The records of 115 patients hospitalized with a prediagnosis of TOA were reviewed for the current study. After hospitalization, TOA was ruled out in 19 patients, and data regarding 96 patients was included for analysis. Twenty-eight (29.2%) patients underwent surgical treatment due to failed antibiotic therapy. Sixty-eight (70.8%) were successfully treated with parenteral antibiotics. Medical treatment failure and need for surgery were more common in patients with a large abscess (volume, > 40 cm3, or diameter, > 5 cm). The group treated by surgical intervention was statistically older than the patients receiving medical treatment (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Although the treatment in TOA may vary according to clinical, sonographic, and laboratory findings; age of patients, the abscess size, and volume were seen as the major factors affecting medical treatment failure. Moreover, TOA treatment should be planned on a more individual basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a common complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), affecting approximately 10–15% of women with PID [1]. It is most commonly seen at the age of 30–40 years in reproductive-age women [2]. The mortality rate associated with TOA was approximately 50% or higher before advances in surgery and the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics [3, 4]. The risk factors for TOA are similar to those of PID, including young age, multiple partners, new sexual partner (within previous three months), history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the patient or their partner, instrumentation of the uterus/interruption of the cervical barrier, termination of pregnancy, insertion of intrauterine device within the past 6 weeks, hysterosalpingography, hysteroscopy, saline infusion sonography, in vitro fertilization, immunosuppression, and endometriosis [5].

TOA is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition. Therapeutic methods include antibiotic therapy, drainage procedures, invasive surgery, and a combination of these interventions. For the majority of small abscesses (< 7 cm in diameter), only antibiotic treatment is sufficient, while drainage or surgical necessity may occur in approximately 25% of cases [6]. In women with an abscess size of less than 9 cm, with no signs of abscess rupture and hemodynamic stability, the clinical guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend medical management as the first treatment approach for TOAs [7]. Abscess size is predictive in determining treatment success with antibiotics alone and length of hospital stay [8].

The aim of this study was to determine whether we could predict the conditions in which medical treatment might fail and surgical necessity emerges, by evaluating the clinical and laboratory findings of women with TOAs treated in our clinic.

Materials and methods

The records of 115 patients who were hospitalized with a prediagnosis of TOA in our department between Jan 2012 and December 2019 were retrospectively reviewed. After hospitalization, TOA was ruled out in 19 patients, and 96 patients were reviewed included for the analysis. The study protocol was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Ankara Training and Research Hospital (approval number 2020/21).

The sonographic diagnosis of TOA was made based on the presence of a complex cystic mass with a thick-irregular wall and irregular internal echo in the pelvis, and the absence of peristalsis [8]. Following the CDC recommendations, the patients were initially treated either with clindamycin and gentamicin or with ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Response to treatment was defined as the absence of fever within 72 h and/or that of acute abdominal symptoms within 48 h.

Demographic and clinical data were reviewed and recorded via medical files and computer-based screening. Age, marital status, gravidity and parity, menopausal status, intrauterine device usage, smoking status, body temperature, clinical and sonographic presentations, initial antibiotic regimens, surgical treatment, laboratory infection parameters at admission, and length of hospital stay were recorded.

The patients were divided into two groups according to surgical (n = 28) or medical (n = 68) treatment received. Demographic parameters, antibiotic regimens, clinical and laboratory findings, length of hospital stay, and TOA sizes were compared. The average volume of the TOAs was calculated by the ellipsoid volume formula (volume = height × width × length × 0.52). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether the distributions of continuous and discrete variables were normal. Mean and standard deviation values were calculated where applicable. Independent samples were investigated using Student’s t-test. The comparison of categorical variables was undertaken using Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess sensitivity and specificity values.

Results

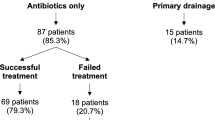

Of the remaining 96 patients, 68 (70.2%) were treated with medical therapy alone, while 28 (29.8%) underwent surgery in addition to medical therapy. The mean age of the patients who received medical treatment was 38.8 ± 8.7 years, which was significantly lower (p = 0.005) compared to the surgically treated group (43.7 ± 8.3 years). The demographic data of the patients are shown in Table 1.

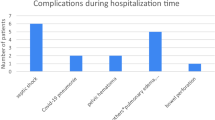

The duration of hospitalization, abscess size, and abscess volume were significantly higher in patients who also underwent surgery compared to those receiving medical treatment alone (p < 0.01). The C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and white blood cell (WBC) count at the time of hospitalization were significantly higher in the surgically treated group compared to the medically treated group (p < 0.05). The laboratory and sonographic findings and body temperature of the patients at the time of hospitalization and their length of hospital stay are summarized in Table 2.

Gentamicin/clindamycin was started in 48.96% (n = 47) of all patients and ceftriaxone/metronidazole was started in 51.04% (n = 49). There was no statistically significant difference between the different treatments groups in terms of the antibiotic regimens used.

The length of hospital stay, age, CRP and ESR values, abscess sizes, and abscess volumes were significantly correlated with the selected treatment (p < 0.01). In addition, abscess volume and abscess size were significantly associated with the length of hospital stay (p < 0.05).

Total abdominal hysterectomy plus bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH+BSO) was performed as the most common surgical procedure (39.3 %), and the least preferred surgical procedure was salpingectomy (unilateral 7%, bilateral 4%). Abscess drainage by laparotomy was performed in four patients, and in one of these patients, ovarian cyst excision was undertaken. The mean age of the patients undergoing TAH+BSO was over 45 years. The preferred surgical procedures are shown in Fig. 1.

A multivariate logistic regression model adjusted for age, TOA size and volume, CRP, ESR, WBC, and body temperature is shown in Table 3. Age and TOA size and volume were found to be independent predictors of a failure of medical management, with the odds ratio (OR) of 1.200 (95% CI 1.086–1.326; p = 0.000) for TOA volume, 1.117 (95% CI 1.031–1.610; P = 0.034) for TOA size, and 1.115 (95% CI 1.020–1.219; p = 0.017) for patient age. According to the ROC analysis, abscess volume, mean abscess size, fever, WBC, ESR, and CRP at admission were useful to predict the outcome of TOA treatment with antibiotics (Fig. 2).

The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that a maximum dimension of TOA size greater than 5.11 cm and a TOA volume greater than 41.9 cm3 were predictive of antibiotic failure (odds ratio, 1.45; 95% CI 1.13–2.10, p = 0.0175, and OR, 1.21; 95% CI 1.12–2.54, p = 0.024). The mean CRP levels, WBC count, ESR and body temperature did not add any additional predictive value beyond that of the mean TOA size and volume in the regression analysis.

Discussion

TOA, a serious complication of PID, results in significantly high morbidity and mortality. A patient diagnosed with TOA is usually given parenteral antibiotics as the first-line treatment for at least 24 h, and when the desired response is obtained, outpatient treatment with oral antibiotics can be continued [7]. If there is no response within 48–72 h, surgery or drainage may be considered [9]. Although the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is usually the first-line option in unruptured TOA, the optimal treatment of TOA is unclear and should be considered individually according to each patient’s clinical and laboratory findings. Approximately 70% of patients with TOA are known to respond to conservative medical treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, while the remainder requires an invasive intervention [10]. This is consistent with the results of our study, in which 70.2% of patients were successfully treated with antibiotic therapy. Identifying the clinical and laboratory findings that will determine the need for surgery in advance may allow for early surgical interventions and shorten the length of hospital stay.

In the current literature, although different factors that cause medical treatment failure are mentioned in relation to TOAs, there is no consensus on this issue. High gravidity and parity, old age, and menopausal status have been shown as epidemiological risk factors for medical treatment failure [11, 12]; however, this may be considered as an emphasis on surgical preference. Many studies have shown that patients receiving medical treatment are significantly younger than those undergoing surgery [11,12,13]. Similarly, medically treated patients in the current study were statistically significantly younger than the patients who needed surgical intervention.

In patients with large adnexal masses, the success rate of antibiotics alone is particularly low [14]. Some studies have reported the failure of conservative treatment and prolonged hospital stay in patients with TOAs larger than 6–9 cm [11, 14, 15]. Large TOA sizes in patients were associated with an increased rate of surgical treatment [16, 17]. In the current study, we also found an increased mean abscess volume and abscess size in surgically treated patients, and furthermore medical treatment failure and need for surgery were more common in patients with a large abscess (volume, > 40 cm3, or diameter, > 5 cm).

This study demonstrated that the WBC count, CRP levels, ESR, and body temperature of the patients with TOA were significantly higher among patients in the surgically treated group; however, they did not have any additional value for predicting the need for surgical treatment. There are many reports investigating the relationship between laboratory findings and the need for surgery [18,19,20,21]. Gungorduk et al. and Devitt et al. showed that the CRP levels and ESR were higher in surgically treated patients [11, 22]. Fouks et al. [23] stated that a simple risk scoring using the abscess size, age, and inflammation markers could similarly predict antibiotic failure in the treatment of TOA.

In cases where medical treatment is unsuccessful, invasive methods should be preferred based on the patient’s age and menopausal status, facilities of the clinic, and the surgeon’s experience. Computer tomography or ultrasound-guided TOA drainage with concomitant antibiotics is effective and safe for the primary or secondary treatment of TOA with some researchers even demonstrating that drainage may be a more successful treatment [24, 25]. TOA patients being mostly in the reproductive age group should not be overlooked in the treatment decision. With the development of minimally invasive methods, laparoscopy is frequently used in the safe surgical treatment of TOA [20]. According to Doğanay et al., laparoscopy presents as the best treatment option in selected cases [26]. In the current study, we performed laparotomy in all patients in the surgically treated group. This was due to either the general health status of the patients not allowing to perform laparoscopy (hemodynamic instability, sepsis, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, huge adnexal mass, etc.) or the preference of the surgeon.

There were certain limitations to our study. Firstly, it was a single-center study which was retrospectively designed, and secondly, the long-term medical data of the included patients was missing.

The main limitations of the current study are the retrospective design and inclusion of patients treated in a single medical center. Also, long-term data regarding the included patients is missing.

Conclusions

Although the treatment in TOA may vary according to the clinical, sonographic and laboratory findings, the abscess size, volume at admission, and patient age were found to be the main factors that indicated the need for surgical treatment. CRP levels, WBC count, ESR, and increased body temperature at admission should also be taken into consideration in the selection of ideal treatment. Finally, the treatment of TOA should be planned on an individual basis considering the clinical and laboratory findings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

McNeeley SG, Hendrix SL, Mazzoni MM et al (1998) Medically sound, cost-effective treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Am J Obstet Gynecol 178(6):1272–1278

Clark JFJ, Moore-Hines S (1979) A study of tubo-ovarian abscess at Howard University Hospital (1965 through 1975). J Natl Med Assoc 71:1109–1111

Pedowitz P, Bloomfield RD (1964) Ruptured adnexal abscess (tuboovarian) with generalized peritonitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 88:721–729

Vermeeren J, Te Linde RW (1954) Intraabdominal rupture of pelvic abscesses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 68:402–409

Chappelland CA, Wiesenfeld HC (2012) Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of severe pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Clin Obstet Gynecol 55(4):893–903

Granberg S, Gjelland K, Ekerhovd E (2009) The management of pelvic abscess. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 23:667–678

Workowski K, Berman S, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59(12):1–110

Topçu HO, Kokanalı K, Güzel AI et al (2014) Risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes in patients with tubo-ovarian abscess. J Obstet Gynaecol 35(7):699–670

Gjelland K, Ekerhovd E, Granberg S (2005) Transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration for treatment of tubo-ovarian abscess: a study of 302 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:1323–1330

Chan GMF, Fong YF, Ng KL (2019) Tubo-ovarian abscesses: epidemiology and predictors for failed response to medical management in an Asian population. Inf D Obstet Gynecol 2019:4161394. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4161394

Dewitt J, Reining A, Allsworth JE, Peipert J (2010) Tuboovarian abscesses: is size associated with duration of hospitalization & complications? Obstet Gynecol Int 2010:847041

Karasu Y, Karadag B, Kavak Comert D, Arslanca T, Kurdoglu Z, Korkmaz V, Ergun Y (2015) When the surgical treatment is suggested in patients with tubo-ovarian abscess? Asian J Pharm Res 5(2):128–133

Halperin R, Levinson O, Yaron M, Bukovsky I, Schneider D (2003) Tubo-ovarian abscess in older women: is the woman’s age a risk factor for failed response to conservative treatment? Gynecol Obstet Investig 55:211–215

Reed SD, Landers DV, Sweet RL (1991) Antibiotic treatment of tuboovarian abscess: comparison of broad-spectrum beta-lactam agents versus clindamycin-containing regimens. Am J Obstet Gynecol 164:1556–1561

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP (2003) Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 157:940–943

Sordia-Hernandez LH, Serrano Castro LG, Sordia-Pineyro MO et al (2016) Comparative study of the clinical features of patients with a tubo-ovarian abscess and patients with severe pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 132:17–19

Lee SW, Rhim CC, Kim JH et al (2016) Predictive markers of tubo-ovarian abscess in pelvic inflammatory disease. Gynecol Obstet Investig 81:97–104

Varghese JC, O’Neill MJ, Gervais DA, Boland GW, Mueller PR (2001) Transvaginal catheter drainage of tuboovarian abscess using the trocar method: technique and literature review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177:139–144

Kinay T, Unlubilgin E, Cirik DA, Kayikcioglu F, Akgul MA, Dolen I (2016) The value of ultrasonographic tubo-ovarian abscess morphology in predicting whether patients will require surgical treatment. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 135:77–81

Bohm MK, Newman L, Satterwhite CL, Tao G, Weinstock HS (2010) Pelvic inflammatory disease among privately insured women, United States. Sex Transm Dis 37:131–136

Habboub AY (2016) Middlemore Hospital experience with tubo-ovarian abscesses: an observational retrospective study. Int J Women's Health 8:325–340

Gungorduk K, Guzel E, Asicioglu O, Yildirim G, Ataser G, Ark C et al (2014) Experience of tubo-ovarian abscess in western Turkey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 124(1):45–50

Fouks Y, Cohen A, Shapira U, Solomon N, Almog B, Levin I (2019) Surgical intervention in patients with tubo-ovarian abscess: clinical predictors and a simple risk score. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 26(3):535–543

Goharkhay N, Verma U, Maggiorotto F (2007) Comparison of CT- or ultrasound-guided drainage with concomitant intravenous antibiotics vs. intravenous antibiotics alone in the management of tubo-ovarian abscesses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 29:65–69

Farid H, Lau TC, Karmon AE, Styer AK (2016) Clinical characteristics associated with antibiotic treatment failure for tuboovarian abscesses. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016:5120293. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5120293

Doganay M, Iskender C, Kilic S, Karayalcin R, Moralioglu O, Kaymak O et al (2011) Treatment approaches in tubo-ovarian abscesses according to scoring system. Bratisl Lek Listy 112(4):200–203

Acknowledgements

We thank Yetkin Karasu who assisted in the statistical analysis of the data.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG performed case selection, analysis of data, and writing of the article. EGY collected the data and assisted in data analysis. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Ankara Training and Research Hospital (approval number 2020/21).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gözüküçük, M., Yıldız, E.G. Is it possible to estimate the need for surgical management in patients with a tubo-ovarian abscess at admission? A retrospective long-term analysis. Gynecol Surg 18, 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-021-01095-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-021-01095-6