Abstract

Background

Ultrasonography is a first-line imaging in the investigation of women’s irregular bleeding and other gynaecological pathologies, e.g. ovarian cysts and early pregnancy problems. However, teaching ultrasound, especially transvaginal scanning, remains a challenge for health professionals. New technology such as simulation may potentially facilitate and expedite the process of learning ultrasound. Simulation may prove to be realistic, very close to real patient scanning experience for the sonographer and objectively able to assist the development of basic skills such as image manipulation, hand-eye coordination and examination technique.

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the face and content validity of a virtual reality simulator (ScanTrainer®, MedaPhor plc, Cardiff, Wales, UK) as reflective of real transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) scanning.

Method

A questionnaire with 14 simulator-related statements was distributed to a number of participants with differing levels of sonography experience in order to determine the level of agreement between the use of the simulator in training and real practice.

Results

There were 36 participants: novices (n = 25) and experts (n = 11) who rated the simulator. Median scores of face validity statements between experts and non-experts using a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS) ratings ranged between 7.5 and 9.0 (p > 0.05) indicated a high level of agreement. Experts’ median scores of content validity statements ranged from 8.4 to 9.0.

Conclusions

The findings confirm that the simulator has the feel and look of real-time scanning with high face validity. Similarly, its tutorial structures and learning steps confirm the content validity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Simulation tools are either simplistic models or complex applications, and regardless of the technology used, a simulator must demonstrate validity to be an effective education tool [1]. This entails gathering evidence from multiple sources to show that the interpretation of image, examination or assessment is sound and sensible [1, 2]. At the outset, validation will usually attempt to confirm the fundamental reasons that these tools need to exist for learning [3,4,5,6]. From an educational perspective, a simulated performance should appear realistic when creating a cognitive-sensory mechanism known as ‘sense of presence’ because it allows the trainee/operator to interact with the remote environment as if s/he were present within the environment [7]. With regard to the role of simulation in developing ultrasound knowledge and skills, the validity and reliability of a simulator system for educational goals must be proven, through structured face, content and construct validity studies [1, 8,9,10].

Face validity is defined as the extent of a simulator’s realism and appropriateness when compared to the actual task [11,12,13], whereas content validity is defined as the extent to which a simulator’s content is representative of the knowledge or skills that have to be learnt in the real environment. This is based on detailed examination of the learning resources, tutorials and tasks [3, 14,15,16]. Hence, in the context of ultrasound, face validity addresses the question of how realistic is the simulator, for example, in examining the female pelvis and how realistic is the simulated feel (haptic sensation) experienced during the examination. Similarly, content validity addresses the question of how useful is the ultrasound simulator in learning relevant skills such as measuring endometrial thickness and foetal biometry [13, 17, 18].

According to McDougall and colleagues [4], Kenney and colleagues [19] and Xiao and colleagues [16], face validity is expressed as the assessment of virtual realism by novices, while content validity refers to experts’ assessment of the suitability of a simulator as a teaching tool. However, reports in the literature are diverse and some authors undertake face validity of a simulator by seeking the opinion of any user including expert and non-expert subjects [12, 13, 15, 20,21,22]. Others have argued that subjects’ experience is required for face validity of any educational instrument [18, 23,24,25,26]. With regard to content validity, it widely refers to experts’ judgement towards the learning content and tasks of a simulator [14, 17, 27,28,29]. Nevertheless, many published studies rely on subjects with different levels of experience in evaluating content validity of a simulator [12, 13, 22, 30,31,32].

The ultrasound simulator [33] enables the student to acquire transabdominal (TAS) or transvaginal ultrasound scanning (TVUS) skills through a series of simulation tutorials, each with one or more assignments that include specified tasks reflecting real ultrasound practice. Upon completion of the tasks, the simulator provides computer-generated individualised student/trainee feedback. The hypotheses were that the simulator was (1) realistic for the purpose of developing ultrasound skills and reflects real-life scanning and (2) the content of its structured learning approach represents the knowledge and psychomotor skills that must be learnt when scanning patients.

The aim of this study was to determine face and content validity of TVUS ScanTrainer. The objectives were (1) to recruit practitioners with varying levels of ultrasound experience from attendees of an international conference and (2) instruct study volunteers to undertake relevant simulator tutorials and complete a structured questionnaire including statements on face and content validity.

Methods

Subjects were voluntarily recruited from delegates visiting the ‘ESGE Simulation Island’ during the 23rd European Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (2014) in Glasgow, Scotland, UK. Each delegate was given a brief, general introduction on the purpose of the study and instructions on how to use the simulator and the relevant tutorials. They gave verbal consent to participate and proceeded to explore specific tasks in three tutorials with the TVUS ScanTrainer (Fig. 1). These were (1) core skills gynaecology which has assignments on assessing the uterus, ovaries and adnexa and measuring the endometrial thickness, (2) core skills early pregnancy which has assignments on assessing the gestational sac, yolk sac as well as evaluating foetal viability and measurements and (3) advanced skills that consisted of several case studies, e.g. ovarian cyst, ectopic pregnancy and twin pregnancy. At the conclusion of the session, subjects completed a short questionnaire. Participants took between 10 and 15 min to complete the three tutorials.

The structured questionnaire (Additional file 1) consisted of two sections: one detailed subjects’ demographic information, previous ultrasound experience and any previous experience with VR simulation or ultrasound mannequins. The other section included simulation-related statements. An expert was defined as a subject who had ultrasonography experience of nearly 2 years or more, conducted daily scanning sessions and considered her/himself as an independent practitioner. Some experts with many years of independent ultrasound experience had less than daily or weekly sessions due to other commitments. A non-expert was defined as having limited experience with ultrasound, had less than 2 years TVUS experience, with occasional or very limited scanning sessions, e.g. once/month, or considered her/himself as a trainee under supervision, newly qualified or not yet competent in TVUS scanning.

Fourteen simulation-related statements/parameters were subjectively scored along a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS) line by marking the point that subjects felt most appropriate, with (0) at one end (very bad) and (10) at the other (very good). Statements 1 to 6 assessed face validity, 7 to 12 evaluated the simulator’s learning content and 13 and 14 were general statements on the value of the simulator as training tool (for practical skill acquisition purpose) and testing tool (for assessment purpose). Ratings on the scale were defined in ‘mm’ as 0–9 (very strongly disagree), 10–19 (strongly disagree), 20–29 (disagree), 30–39 (moderately disagree), 40–49 (mildly disagree), 50 (undecided), 51–59 (mildly agree), 60–69 (moderately agree), 70–79 (agree), 80–89 (strongly agree), 90–100 (very strongly agree). Millimetres were considered for accurate readings of subjects’ marking on scale and later converted to centimetres for final analysis.

The study was conducted in accordance with the general terms and conditions of the South East Wales Research Ethics Committee SEWREC (NHS REC Reference 10/WSE02/75) approval and approval of the study protocol by the congress organising committee.

Statistical data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics software version 20.0 was used for statistical analysis. Median values were chosen in preference to mean values as the data were not normally distributed. Median scores and box plots were constructed for each statement as rated by non-experts and experts. Box plots and whiskers represented the median, first and third quartiles, minimum, maximum and outliers of scores obtained by expert and non-expert ratings of the 13 statements. Face validity and general statement items were stratified by expert and non-expert status, while content validity data were reported for experts only. Differences between experts and non-expert ratings were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test using a p value ≤ 0.05 to indicate significance.

Results

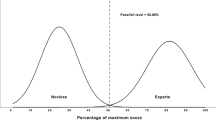

Demographic: Thirty-six subjects, 24 females (67%) and 12 males (33%), participated in this pilot study. Nine were UK-based and 27 were based in other European countries. Eleven subjects (31% expert group) rated themselves as skilled with more than 2 years of experience and practiced independently (n = 10) or with 1 to 2 years of experience and had daily ultrasound sessions (n = 1). Twenty-five subjects (69% non-expert group) were trainees under supervision and included two subjects with more than 2 years TAS experience and limited TVUS scanning. Median age for the expert group was 51 years (range 32–67) and 31 years (range 25–39) for the non-expert group. The median ultrasound experience for experts was more than 2 years and for non-experts was 6 to 11 months. Further breakdown of demographics and years of ultrasound experience is detailed in Table 1.

Face validity: Median scores of face validity statements are detailed in Table 2. In summary, experts’ and non-experts’ ratings ranged between 7.5 and 9.0 and were slightly higher than those by experts in two statements (2 and 6) relating to ‘realism of the simulator to simulate the TVUS scan of female pelvis and realism of the simulator to provide actual action of all buttons provided in the control panel’. Two statements (1 and 3) were rated lower by experts and related to ‘relevance of the simulator for actual TVUS scanning and the realism of the simulator to simulate the movements possibly required to perform in the female pelvic anatomy (uterus, ovaries/adnexa, Pouch of Douglas POD)’. The remaining two statements (4 and 5) referring to ‘realism of the ultrasound image generated during the performance and force feedback provided on the operator’s hand to simulate real scan’ were equally rated. Two general statements (13 and 14) were also rated lower by experts. However, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups’ ratings in all statements (Table 1). Median values and box plots of the eight statements in the two groups are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Box plots represented the median, first and third quartiles, minimum, maximum and outliers of scores obtained by expert and non-expert ratings of the six face validity statements. Dots (outliers) represented those experts who scored lower than others and the number referred to participant’s code number in data analysis and that did not relate to score value

Box plots represented the median, first and third quartiles, minimum, maximum and outliers of scores obtained by expert and non-expert ratings of the two general validity statements on the simulator as training and testing tool. Dots (outliers) represented those experts who scored lower than others and the number referred to participant’s code number in data analysis and that did not relate to score value

Content validity: Experts’ median scores of content validity statements ranged from 8.4 to 9.0 and are detailed in Table 3. Median values and box plots of the six statements are shown in Fig. 4.

Box plots represented the median, first and third quartiles, minimum, maximum and outliers of scores obtained by expert and non-expert ratings of the six content validity statements. Dots (outliers) represented those experts who scored lower than others and the number referred to participant’s code number in data analysis and that did not relate to score value

Discussion

In this study, the ScanTrainer® simulator demonstrated high face and content validity and its overall value as a training and testing tool received high ratings as well. To accurately measure participants’ level of agreement with relevant statements, VAS method was used in the questionnaire [34]. Higher ratings were given by non-experts than experts with regard to ‘relevance of the simulator to actual TVUS’ and ‘its realism to simulate the movements required to perform in the examination of the female pelvis’ (statements 1 and 3) highlighting the fact that such realism is crucial for non-experts for several reasons. This may be because experts need to develop greater understanding of the strengths and limitations of the simulator compared to trainees [35]. Alternatively, beginners in the early stages of learning ultrasound skills are able to address their learning needs through simulated learning compared to the experts who expect variety and advanced or more complex performance rather than basic tutorials [12].

There are no comparable ‘face and content’ validity studies addressing virtual reality simulators for TVUS in obstetrics and gynaecology have been published in the literature. In a face validity study of the dVT robotic surgery simulator, experts rated the simulator as less useful for training experts than for students/juniors and pointed out to the experts’ need for more critical and advanced procedures in gynaecological surgery and that simulators specifically designed for learning basic skills are less preferable to experts [32]. Creating simulated scenarios to correspond to real ones is always a challenge [3, 29, 36, 37].

Experts’ ratings were higher for two statements relating to the realism of the simulator to simulate the TVUS scan of a female pelvis and in providing actual action of all buttons in the control panel (statements 2 and 6) This may stem from non-experts’ limited knowledge and experience, or they might not be familiar with the measurement possibilities of virtual simulators [20, 23]. Similarly, Weidenbach and colleagues [1] argued that experts gave a better grading for the realism of the EchoCom echocardiography simulator because they were not distracted to drawbacks such as mannequin size and its surface properties, which were harder and more slippery than the human skin, and that experts scanned more instinctively. The author noted that this mental flexibility seemed to be as yet underdeveloped in beginners.

Non-experts’ and experts’ ratings were similar when evaluating the realism of the ultrasound image generated during the performance and the force feedback provided onto the operator’s hand (statements 4 and 5). Force feedback (haptics) scored 7.5 out of 10, the lowest score in this study. Similar to this study, Chalasani and colleagues [38] reported low face validity ratings for the haptic force-feedback device of a transrectal ultrasound TRUS-guided prostatic biopsy virtual reality simulator (experts’ lifelike rating 64% and novices’ 67%) even though the author pointed out that haptics, often very difficult to replicate in a simulator environment, were realistic. Haptics will not replace the real-patient scan experience but should enhance the learning approach and improve self-confidence. A further factor is that the ScanTrainer’s haptic device can be tailored to three force feedback levels: normal resistance (most realistic), reduced and minimal (lowest) designed to avoid overheating during heavy use, and it is likely that a lower force feedback setting might have contributed to the lower scores.

The role of force feedback in laparoscopic surgery is not clear [20]. Improving the realism of the simulator and its anatomical structures increases costs considerably due to increased demands for more complex hardware and software. In contrast, Lin and colleagues [39] encouraged learning of bone-sawing skills with simulators that provide force feedback rather than not, confirming the importance of force feedback when seeking to enhance hand-eye coordination. With regard to ScanTrainer, virtual ultrasound and haptics are used instead of a mannequin allowing measurement of the force applied to the probe and provide a somewhat realistic force-feedback during scanning. However, it still has the limitation of allowing a lower range of movements to the probe while lacking a simulated environment exemplified by the absence of a physical mannequin [40].

There are numerous simulator systems in usage particularly in the fields of laparoscopy and endoscopy, and several authors emphasised the importance of evaluating their content, including reviewing each learning task and assessing its overall value to determine whether it is appropriate for the test and whether the test contains several steps and skills for practice [12, 17, 31, 38]. In this study, experts’ data were used to assess content validity. They had adequate time to review the simulator’s learning resources, help functionality ‘ScanTutor’, read the task-specific instructions and undertake specified tasks before going on to the next step in the same tutorial. In addition, participants had the opportunity to review feedback on their performance in the respective tasks. The results of this study demonstrated that the simulator’s content and metrics were appropriate and relevant for ultrasound practice.

There are a number of published content validity studies in ultrasound simulation, such as the educational curriculum for ultrasonic propulsion to treat urinary tract calculi [41], web-based assessment of the extended focused assessment sonography in trauma (EFAST) [2] and validation of the objective structured assessment of technical skills for duplex assessment of arterial stenosis (DUOSATS) [42] which is not based on virtual reality simulator devices. Shumard and colleagues [43] reported on face and content validity of a novel second trimester uterine evacuation task trainer designed to train doctors to perform simulated dilatation and evacuation under ultrasound guidance. Although all respondents were residents with limited ultrasound experience, they rated the task trainer as excellent.

Other studies evaluated the effectiveness of simulation-based training in obstetrics and gynaecology ultrasound, whether to investigate the construct validity of a simulator system [9, 40, 44, 45] or to compare simulation training to conventional methods such as theoretical lectures and hands-on training on patients [10, 46].

Feedback that is automatically generated immediately after a practical simulator session should enhance trainees’ knowledge and ability to reflect critically on their performance and improve their skills [47]. However, the big challenge is to determine how accurate, realistic and trusted the feedback is and, thus, should also be validated appropriately.

Validation studies at national scientific meetings have been reported previously [25, 48]. They offer researchers a rich environment where subjects from different backgrounds and levels of experience are present in one place at the same time. A potential limitation of the study is that it did not determine in advance the sample size required to obtain a reliable result for face and content validation. There is no agreement on the adequacy of sample size in such studies [12, 13]. The number of subjects in this study was higher, and the findings are consistent with others [18, 22, 31, 49]. In addition, many face and content validity studies of simulators were based on smaller sample size compared to the current study [13, 19, 30, 36, 50, 51]. A larger number of participants in this study might have improved the confidence in the results [2]. Participants in this study were from different UK and European institutions unlike others who were from single academic institution [41]; thus, it may be more widely generalizable.

Conclusions

In summary, this study confirms that ScanTrainer simulator has the feel and look (face validity) and tutorial structure (content validity) to be realistic and relevant for actual TVUS scanning. This study also concurs with the notion that advancing computer technologies have been able to incorporate virtual reality into training to facilitate the practice of basic skills as well as complex procedures that leave little room for error or mistake [3, 10, 24, 20]. Equally, such simulators should be part of the skill training labs in teaching hospitals as it is recommended for endoscopic surgery [52, 53]. It should be subject to an ongoing validation to address trainees’ learning needs, provide a structured training path and provide validated test procedures with the global and final aim to improve patient care and safety [30, 31, 36, 52].

References

Weidenbach M, Rázek V, Wild F, Khambadkone S, Berlage T, Janousek J, Marek J (2009) Simulation of congenital heart defects: a novel way of training in echocardiography. Heart 95(8):636–641

Markowitz JE, Hwang JQ, Moore CL (2011) Development and validation of a web-based assessment tool for the extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma examination. J Ultrasound Med 30(3):371–375

Carter FJ, Schijven MP, Aggarwal R, Grantcharov T, Francis NK, Hanna GB, Jakimowicz JJ (2005) Consensus guidelines for validation of virtual reality surgical simulators. Surg Endosc 19:1523–1532

McDougall M, Corica FA, Boker JR, Sala LG, Stoliar G, Borin JF, Chu FT, Clayman RV (2006) Construct validity testing of a laparoscopic surgical simulator. J Am Coll Surg 202(5):779–787

Gilliam AD, Acton ST (2007) Echocardiographic simulation for validation of automated segmentation methods. Image Processing, ICIP 2007. IEEE Int Conf 5:529–532

Wilfong DN, Falsetti DJ, McKinnon JL, Daniel LH, Wan QC (2011) The effects of virtual intravenous and patient simulator training compared to the traditional approach of teaching nurses: a research project on peripheral i.v. catheter insertion. J Infus Nurs 34(1):55–62

Aiello P, D’Elia F, Di Tore S, Sibilio M (2012) A constructivist approach to virtual reality for experiential learning. E-Lear Digital Media 9(3):317–324

Wright MC, Segall N, Hobbs G, Phillips-Bute B, Maynard L, Taekman JM (2013) Standardized assessment for evaluation of team skills: validity and feasibility. Soc Simul Healthc 8:292–303

Madsen ME, Konge L, Norgaard LN, Tabor A, Ringsted C, Klemmensen A, Ottesen B, Tolsgaard M (2014) Assessment of performance and learning curves on a virtual reality ultrasound simulator. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 44(6):693–699

Tolsgaard M, Ringsted C, Dreisler E, Nørgaard LN, Petersen JH, Madsen ME, Freiesleben NL, Sørensen JL, Tabor A (2015) Sustained effect of simulation-based ultrasound training on clinical performance: a randomized trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 46(3):312–318

Byrne A, Greaves J (2001) Assessment instruments used during anaesthetic simulation: review of published studies. Br J Anaesth 86(3):445–450

Hung AJ, Zehnder P, Patil MB, Cai J, Ng CK, Aron M, Gill IS, Desai MM (2011) Face, content and construct validity of a novel robotic surgery simulator. J Urol 186(3):1019–1024

Alzahrani T, Haddad R, Alkhayal A, Delisle J, Drudi L, Gotlieb W, Fraser S, Bergman S, Bladou F, Andonian S, Anidjar M (2013) Validation of the da Vinci surgical skill simulator across three surgical disciplines. Can Urol Assoc J 7(7–8):520–529

Nicholson W, Patel A, Niazi K, Palmer S, Helmy T, Gallagher A (2006) Face and content validation of virtual reality simulation for carotid angiography. Simul Healthc 1(3):147–150

Schreuder HW, van Dongen KW, Roeleveld SJ, Schijven MP, Broeders IA (2009) Face and construct validity of virtual reality simulation of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200(5):540 e541–540 e548

Xiao D, Jakimowicz JJ, Albayrak A, Buzink SN, Botden SM, Goossens RH (2014) Face, content, and construct validity of a novel portable ergonomic simulator for basic laparoscopic skills. J Surg Educ 71(1):65–72

Seixas-Mikelus S, Stegemann AP, Kesavadas T, Srimathveeravalli G, Sathyaseelan G, Chandrasekhar R, Wilding GE, Peabody JO, Guru KA (2011) Content validation of a novel robotic surgical simulator. BJU Int 107(7):1130–1135

Dulan G, Rege RV, Hogg DC, Gilberg-Fisher KK, Tesfay ST, Scott DJ (2012) Content and face validity of a comprehensive robotic skills training program for general surgery, urology, and gynecology. Am J Surg 203(4):535–539

Kenney PA, Wszolek MF, Gould JJ, Lobertino JA, Moinzadeh A (2009) Face, content, and construct validity of dV-trainer, a novel virtual reality simulator for robotic surgery. Urology 73(6):1288–1292

Verdaasdonk EG, Stassen LP, Monteny LJ, Dankelman J (2006) Validation of a new basic virtual reality simulator for training of basic endoscopic skills: the SIMENDO. Surg Endosc 20(3):511–518

Seixas-Mikelus S, Kesavadas T, Srimathveeravalli G, Chandrasekhar R, Wilding GE, Guru KA (2010) Face validation of a novel robotic surgical simulator. Urology 76(2):357–360

Kelly D, Margules AC, Kundavaram CR, Narins H, Gomella LG, Trabulsi EJ, Lallas CD (2012) Face, content, and construct validation of the da Vinci skills simulator. Urology 79(5):1068–1072

Schijven M, Jakimowicz J (2002) Face-, expert, and referent validity of the Xitact LS500 laparoscopy simulator. Surg Endosc 16(12):1764–1770

Sweet R, Kowalewski T, Oppenheimer P, Weghorst S, Satava R (2004) Face, content and construct validity of the University of Washington virtual reality transurethral prostate resection trainer. J Urol 172(5):1953–1957

Maithel S, Sierra R, Korndorffer J, Neumann P, Dawson S, Callery M, Jones D, Scott D (2006) Construct and face validity of MIST-VR, Endotower, and CELTS, are we ready for skills assessment using simulators? Surg Endosc 20:104–112

Aydin A, Ahmed K, Brewin J, Khan MS, Dasgupta P, Aho T (2014) Face and content validation of the prostatic hyperplasia model and holmium laser surgery simulator. J Surg Educ 71(3):339–344

Fisher J, Binenbaum G, Tapino P, Volpe NJ (2006) Development and face and content validity of an eye surgical skills assessment test for ophthalmology residents. Ophthalmology 113(12):2364–2370

Scott DJ, Cendan JC, Pugh CM, Minter RM, Dunnington GL, Kozar RA (2008) The changing face of surgical education: simulation as the new paradigm. J Surg Res 147(2):189–193

Gould D (2010) Using simulation for interventional radiology training. Br J Radiol 83:546–553

Vick LR, Vick KD, Borman KR, Salameh JR (2007) Face, content, and construct validities of inanimate intestinal anastomoses simulation. J Surg Educ 64(6):365–368

Gavazzi A, Bahsoun A, Haute W, Ahmed K, Elhage O, Jaye P, Khan M, Dasgupta P (2011) Face, content and construct validity of a virtual reality simulator for robotic surgery (SEP Robot). Ann R Coll Surg Engl 93(2):152–156

Schreuder HR, Persson JE, Wolswijk RG, Ihse I, Schijven MP, Verheijen RH (2014) Validation of a novel virtual reality simulator for robotic surgery. Sci World J 2014:30

Medaphor® Plc, The ScanTrainer (2016) [online] Available at http://www.medaphor.com/scantrainer/ [Accessed 30 June 2016]

Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM (2003) Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain 4(7):407–414

Shanmugan S, Leblanc F, Senagore AJ, Ellis CN, Stein SL, Khan S, Delaney CP, Champagne BJ (2014) Virtual reality simulator training for laparoscopic colectomy: what metrics have construct validity? Dis Colon rectum 57(2):210–214

O'Leary SJ, Hutchins MA, Stevenson DR, Gunn C, Krumpholz A, Kennedy G, Tykocinski M, Dahm M, Pyman B (2008) Validation of a networked virtual reality simulation of temporal bone surgery. Laryngoscope 118(6):1040–1046

de Vries AH, van Genugten HG, Hendrikx AJ, Koldewijn EL, Schout BM, Tjiam IM, van Merriënboer JJ, Muijtjens AM, Wagner C (2016) The Simbla TURBT simulator in urological residency training: from needs analysis to validation. J Endourol 30(5):580–587

Chalasani V, Cool DW, Sherebrin S, Fenster A, Chin J, Izawa JI (2011) Development and validation of a virtual reality transrectal ultrasound guided prostatic biopsy simulator. Can Urol Assoc J 5(1):19–26

Lin Y, Wang X, Wu F, Chen X, Wang C, Shen G (2014) Development and validation of a surgical training simulator with haptic feedback for learning bone-sawing skill. J Biomed Inform 48:122–129

Chalouhi GE, Bernardi V, Gueneuc A, Houssin I, Stirnemann JJ, Ville Y (2015) Evaluation of trainees’ ability to perform obstetrical ultrasound using simulation: challenges and opportunities. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(4):525.e1–525.e8

Hsi RS, Dunmire B, Cunitz BW, He X, Sorensen MD, Harper JD, Bailey MR, Lendvay TS (2014) Content and face validation of a curriculum for ultrasonic propulsion of calculi in a human renal model. J Endourol 28(4):459–463

Jaffer U, Singh P, Pandey VA, Aslam M, Standfield NJ (2014) Validation of a novel duplex ultrasound objective structured assessment of technical skills (DUOSATS) for arterial stenosis detection. Heart Lung Vessel 6(2):92–104

Shumard KM, Akoma UN, Street LM, Brost BC, Nitsche JF (2015) Development of a novel task trainer for second trimester ultrasound-guided uterine evacuation. Simul Healthc 10(1):49–53

Maul H, Scharf A, Baier P, Wüstemann M, Günter HH, Gebauer G, Sohn C (2004) Ultrasound simulators: experience with the SonoTrainer and comparative review of other training systems. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 24(5):581–585

Merz E (2006) Ultrasound simulator—an ideal supplemental tool for mastering the diagnostics of fetal malformations or an illusion? Ultraschall in Med 27(4):321–323

Williams CJ, Edie JC, Mulloy B, Flinton DM, Harrison G (2013) Transvaginal ultrasound simulation and its effect on trainee confidence levels: a replacement for initial clinical training? Ultrasound 21(2):50–56

Cline BC, Badejo AO, Rivest II, Scanlon JR, Taylor WC, Gerling GJ (2008) Human performance metrics for a virtual reality simulator to train chest tube insertion. IEEE Systems Inf Eng Des Symp:168–173 doi:10.1109/SIEDS.2008.4559705

Stefanidis D, Korndorffer JR, Markley S, Sierra R, Heniford BT, Scott DJ (2007) Closing the gap in operative performance between novices and experts: does harder mean better for laparoscopic simulator training? J Am Coll Surg 205(2):307–313

White MA, Dehaan AP, Stephens DD, Maes AA, Maatman TJ (2010) Validation of a high fidelity adult ureteroscopy and renoscopy simulator. J Urol 183(2):673–677

Bright E, Vine S, Wilson MR, Masters RS, McGrath JS (2012) Face validity, construct validity and training benefits of a virtual reality turp simulator. Int J Surg 10(3):163–166

Shetty S, Panait L, Baranoski J, Dudrick SJ, Bell RL, Roberts KE, Duffy AJ (2012) Construct and face validity of a virtual reality-based camera navigation curriculum. J Surg Res 177(2):191–195

Campo R, Puga M, Meier Furst R, Wattiez A, De Wilde RL (2014) Excellence needs training “Certified programme in endoscopic surgery”. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 6(4):240–244

Campo R, Wattiez A, Tanos V, Di Spiezio SA, Grimbizis G, Wallwiener D, Brucker S, Puga M, Molinas R, O’Donovan P, Deprest J, Van Belle Y, Lissens A, Herrmann A, Tahir M, Benedetto C, Siebert I, Rabischong B, De Wilde RL (2016) Gynaecological endoscopic surgical education and assessment. A diploma programme in gynaecological endoscopic surgery. Gynecol Surg 13:133–137

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Portions of this research were presented in the UK and international. Special thanks to the European Academy for Gynaecological Surgery and the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy for their support and for providing the facilities at simulation island during the 23rd European Congress of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (2014) in Glasgow, Scotland, UK. We are thankful to all the participants for sharing their experience and valuable feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and NA are the principal investigators and conceived the study. NA and NP were the co-supervisors of the PhD thesis. AA, NA, RC, VT, GG, and YvB designed the study and questionnaire. AA undertook the study and carried out the statistical analysis under the supervision of KH. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved it before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Amal Alsalamah was a PhD student funded by the Government of Saudi Arabia. Nazar Amso is a founder of, owns stocks in and is a board member of MedaPhor, a spin-off company of Cardiff University. He is a co-inventor of a patent for ultrasound simulation training system.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Face Validity Questionnaire: the ScanTrainer Ultrasound Simulator. (DOCX 207 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsalamah, A., Campo, R., Tanos, V. et al. Face and content validity of the virtual reality simulator ‘ScanTrainer®’. Gynecol Surg 14, 18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-017-1020-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10397-017-1020-6