Abstract

Background

Erenumab was approved in Europe for migraine prevention in patients with ≥ 4 monthly migraine days (MMDs). In Spain, Novartis started a personalized managed access program, which allowed free access to erenumab before official reimbursement. The Spanish Neurological Society started a prospective registry to evaluate real-world effectiveness and tolerability, and all Spanish headache experts were invited to participate. We present their first results.

Methods

Patients fulfilled the ICHD-3 criteria for migraine and had ≥ 4 MMDs. Sociodemographic and clinical data were registered as well as MMDs, monthly headache days, MHDs, prior and concomitant preventive treatment, medication overuse headache (MOH), migraine evolution, adverse events, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs): headache impact test (HIT-6), migraine disability assessment questionnaire (MIDAS), and patient global improvement change (PGIC). A > 50% reduction of MMDs after 12 weeks was considered as a response.

Results

We included 210 patients (female 86.7%, mean age 46.4 years old) from 22 Spanish hospitals from February 2019 to June 2020. Most patients (89.5%) suffered from chronic migraine with a mean evolution of 8.6 years. MOH was present in 70% of patients, and 17.1% had migraine with aura. Patients had failed a mean of 7.8 preventive treatments at baseline (botulinum toxin type A—BoNT/A—had been used by 95.2% of patients). Most patients (67.6%) started with erenumab 70 mg. Sixty-one percent of patients were also simultaneously taking oral preventive drugs and 27.6% were getting simultaneous BoNT/A. Responder rate was 37.1% and the mean reduction of MMDs and MHDs was -6.28 and -8.6, respectively. Changes in PROs were: MIDAS: -35 points, HIT-6: -11.6 points, PIGC: 4.7 points. Predictors of good response were prior HIT-6 score < 80 points (p = 0.01), ≤ 5 prior preventive treatment failures (p = 0.026), absence of MOH (p = 0.039), and simultaneous BoNT/A treatment (p < 0.001). Twenty percent of patients had an adverse event, but only two of them were severe (0.9%), which led to treatment discontinuation. Mild constipation was the most frequent adverse event (8.1%).

Conclusions

In real-life, in a personalized managed access program, erenumab shows a good effectiveness profile and an excellent tolerability in migraine prevention in our cohort of refractory patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migraine is the second leading neurological cause of disability and the first among young women according to the GBD2019 [1]; and approximately 38% of migraine patients [2] need a preventive treatment to reduce this disability. In Spain, several first line preventive drugs for episodic migraine (EM) are available: topiramate, sodium valproate, amitriptyline, flunarizine and beta-blockers, but only botulinum toxin type A (BoNT/A) and topiramate are available for chronic migraine (CM) [3].

The number of monthly migraine days (MMDs) after 12 weeks of treatment is the main variable of efficacy for a preventive drug in migraine [4], despite the known decrease in prevention adherence beyond 12 weeks [5,6,7]. The loss of effectiveness and side effects account for this progressive reduction in adherence. For these reasons, we urgently needed new preventive drugs, and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies (CGRP mAbs) have been developed to cover these needs.

CGRP is a neuropeptide distributed throughout the human body and highly concentrated in the trigeminovascular system [8]. The levels of CGRP are increased during the migraine attack in blood, tears, saliva, and cerebrospinal fluid, and normalized after the attack [9, 10]. They are also permanently increased during CM [11]. Moreover, the intravenous administration of CGRP causes migraine-like headaches in migraine patients and voluntaries [12]. Therefore, CGRP is an excellent target for migraine therapy.

At present, there are three subcutaneous CGRP mAbs marketed in Spain: erenumab (Aimovig®), galcanezumab (Emgality®) and fremanezumab (Ajovy®). CGRP mAbs block the CGRP receptor (erenumab) or the ligand itself (galcanezumab and fremanezumab). Their phase II [13,14,15,16,17,18] and phase III [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] trials against placebo have demonstrated the excellent safety and efficacy profile in migraine prevention [39]. Furthermore, several meta-analyzes have supported these results [34,35,36,37,38,39]. The conclusions that can be drawn from all these studies are that there appear to be no significant differences in safety between each of the CGRPs, and that all of them are superior in efficacy to placebo.

Erenumab was the first CGRP mAb approved for migraine prevention in Europe. The European Medicines Agency approval was communicated the 26th of July 2018 for patients with at least 4 MMDs for the last three months. The Spanish Medicines Agency authorized a personalized managed access program that allowed neurologists to treat patients before the official reimbursement in January 2019. In the same date, the Headache Study Group of the Spanish Neurological Society (GECSEN) started MAB-MIG. This is a prospective, independent, and multicentre registry of migraine patients treated with CGRP mAbs promoted by GECSEN, created to evaluate their real-world effectiveness and tolerability by inviting headache specialists around the country. Here, we present the data of effectiveness and tolerability of the first 210 included migraine Spanish patients after 12 weeks treatment with erenumab.

Methods

The MAB-MIG scientific committee is constituted by the members of GECSEN board (R. Belvís, S. Santos, G. Latorre and C. Gonzalez-Oria) plus two independent advisors (P. Pozo-Rosich and R. Leira). This committee selected the variables and advised on the design of the database. It also resolved queries of the investigators and assessed the final database and the statistical analyses. Each investigator acted according to their clinical criteria, considering the European Medicines Agency and the Spanish Neurology Society guidelines [3] that establish the indication of erenumab from at least 4 MMDs. The recommendations on erenumab treatment in migraine, proposed by international experts [3, 40,41,42], were made available to researchers.

All patients included fulfilled the migraine criteria of the International Headache Society (IHS) [43]. Patients were between 18 and 65 years old, had ≥ 4 MMDs for the last three months and were treated with erenumab during a minimum 12-week period. Migraine started in their lives before age 50 and all of them had the migraine diagnosis for a minimum of one year prior to inclusion in the registry. Patients with recent cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events (in the previous three months) were excluded.

We collected the following variables:

-

1.

Demographical data: gender and age.

-

2.

Clinical data as migraine form (with/without aura), MMD and MHD (number of mean monthly headache days). According to these definitions, we considered CM (≥ 15 MHDs) versus episodic migraine-EM (< 15 MHDs). Moreover, the EM group was subdivided into HFEM (10 to 14 MHDs) and low-frequency episodic migraine (LFEM; < 10 MHDs).

-

3.

Effectiveness variables. The following variables were collected at baseline and after 12-weeks treatment with erenumab: number of MMDs and MHDs, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including headache impact test (HIT-6) score and the migraine disability assessment questionnaire (MIDAS) score. Finally, patients implemented a patient global impact changes (PGIC) scale to evaluate their satisfaction.

According to the IHS guidelines of controlled trials in migraine [4], number of MMDs was considered the primary endpoint. Response was considered when a reduction in the number of migraine days > 50% was observed between baseline and week 12 of treatment with erenumab.

Additionally, we collected other variables: prior preventives drugs taken, including BoNT/A, previous overuse of acute medication, erenumab treatment alone or in combination with another preventive drug, initial erenumab doses, and if there was a change in the erenumab dosage after 12 weeks. Other changes measured were conversion from CM to EM, and medication overuse headache (MOH).

Tolerability analyses

We collected all adverse events (AEs), and the MAB-MIG scientific committee classified them as related or non-related to erenumab treatment. According to Good Clinical Practice guidelines, we classified adverse events as mild, moderate, or severe, and we collected the dropout rate.

For statistical analysis we used the SPSS software (version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results were expressed as means and standard deviations or as absolute number and percentages. Patient data were classified into two groups: baseline visit and 12-week visit. Comparisons have been made using the Student's t-test for quantitative variables and contingency tables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. When the distribution of the data went out of normality, we used the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Finally, MAB-MIG was classified as a low-intervention clinical trial by the Spanish Medicines Agency and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Investigation with Medicines of the Health Area of Valladolid (PI 20–1790). The name of the participant hospitals was anonymized and the information regarding their patients was sent in encrypted form.

Results

We included 210 patients from 22 Spanish hospitals, from February 2019 to June 2020, who had completed at least 12 weeks of erenumab treatment. The included centres had a homogeneous geographic distribution around the country. The mean age was 46.4 years-old (18–65), and 86.7% of patients were women.

The mean migraine duration was 26.5 years (3–25 years). Most patients (89.5%) had CM with an average evolution of 8.6 years (3 months-25 years) and the remaining presented HFEM (10.5%). Seventy percent of patients presented MOH, and 17.1% fulfilled migraine with aura criteria. The average of MMDs was 17.1 days (4–30), and of MHDs was 23.5 days. The mean MIDAS score was 101.9 points, and the mean HIT-6 score was 68.8 points.

Patients had failed a mean of 7.8 (2–20) preventive treatments at baseline including BoNT/A. The later had been used by 95.2% of patients. The most frequently used oral preventive drugs were topiramate (98.2%), amitriptyline (98.2%), flunarizine (94.7%) and beta-blockers (92.9%).

The initial dose of erenumab was 70 mg in 67.6% of patients and 140 mg in the remaining 32.4%. Regarding simultaneous preventive treatments, only 39.5% patients received exclusively erenumab as preventive treatment, and in the remaining patients (60.5%) erenumab was added to another preventive drug that the patient already took. Thus, 27.6% of patients received BoNT/A plus erenumab, 12,2% topiramate plus erenumab and 49.1% a miscellanea of oral preventive drugs plus erenumab.

Regarding effectiveness (Table 1), the responder rate was 37.1%, and the mean reduction in MMDs was 6.5 days (from 17.1 to 11 days). MHDs were also reduced in 8.6 days (from 23.5 to 14.9 days).

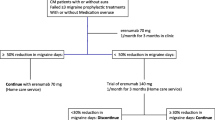

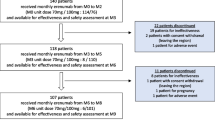

After the 12-week period of treatment (Fig. 1), 28 patients (13.3%) discontinued the treatment. The reasons were: 1) excellent effectiveness that allowed to achieve the conversion to LFEM (20 patients; 9.5%), 2) lack of effectiveness (4 patients; 1.9%), and 3) AEs (4 patients; 1.9%).

The remaining 182 patients (86.7%) continued with erenumab treatment: with the same dose (44.7%), while 41,9% increased the dose thereafter (Fig. 1). After three months of follow-up, 14.8% continued to receive simultaneously BoNT/A and 50% were still under treatment with oral preventive drugs. We want remark that 69 patients (32.8%) continued erenumab despite of they achieved to convert CM into HFEM.

Regarding PROs (Table 1): MIDAS score was reduced 35 points (from 101.9 to 66.9), HIT-6 was reduced 11.6 points (from 68.8 to 57.2) and the mean PIGC assessment was 4.7 points.

We also tried to identify predictive response factors. In this way we found a cut-off point in 5.9 previous preventives failures (p = 0.026) (Table 2) above which only the 10% of patients responded to erenumab treatment. Other predictive factors were MIDAS score < 100 points (p = 0.006), < 80 points in HIT-6 score (p = 0.01), and absence of MOH (p = 0.039). All the responder patients showed a HIT-6 score < 80 points making this index in a strong predictor factor of response at this cut point.

None of the erenumab doses, 70 or 140 mg, showed a better statistical power as predictor of good response than the other (p = 0.647). However, the simultaneous BoNT/A treatment showed the strongest predictor power of a good response (p < 0.001). On the contrary, simultaneous oral preventives did not predict the response (p = 0.213).

In addition, the presence of aura showed a non-significant tendency as a predictor factor of good response (p = 0.088). However, age (p = 0.557), gender (p = 0.294), the form of migraine HFEM/CM (p = 0.727), and evolution of CM (p = 0.514) did not show any association to response.

Finally, regarding tolerability, the percentage of AEs was 20%, but only four patients (1.9%), suffered severe adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation. Two patients had a skin rash attributed to the first erenumab injection; the other two patients presented AEs not related to erenumab: one patient, under paroxetine treatment, presented a serotoninergic syndrome while overusing zolmitriptan; and the other one was diagnosed of cutaneous melanoma, but the skin lesion existed previously to the erenumab treatment onset.

Specifically, forty-two patients presented 57 AEs, being constipation the most frequent (7.6%). No patients needed treatment or consultation by this AEs. Table 3 details AEs reported by patients after 12 weeks of treatment with erenumab.

Finally, we did not find any predictive factor of AEs, but the dose of 140 mg showed a non-significant tendency to present more AEs than the dose of 70 mg (p = 0.069).

Discussion

We present the first multicentre and prospective real-world experience of erenumab in the preventive treatment of migraine in Spain. Erenumab presents an excellent tolerability profile in our registry, but a slightly lower effectiveness, response rate of 37%, comparing to 39–50% that is the average of phase III clinical trials [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], open-label extension studies [44,45,46], and meta-analysis [34,35,36,37,38,39].

This can be attributed to the fact that most of the 210 patients included were highly refractory CM patients and therefore would have been excluded from clinical trials [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. For example, the LIBERTY trial [23] analysed erenumab versus placebo in 246 patients with EM who were unsuccessfully treated (in terms of efficacy or tolerability, or both) with 2–4 preventive treatments. The erenumab response rate reported was 50% [23]. Our response rate is lower, but it must be considered that our patients were more refractory (they failed an average of 7 previous preventives), the majority had CM and part of the study was carried out during the most serious phase of the COVID-pandemic.

Another explanation could be that the more frequent erenumab initial dose prescribed was 70 mg because initial dose was a discretionary decision of the investigator. Since patients included in our study have a long history of migraine, a high number of MMDs, numerous failures to preventive migraine drugs and high impact in HIT-6 and MIDAS scales compared with patients from clinical trials, perhaps effectiveness could have been better if all the investigators had started the treatment with the 140 mg dose.

As expected, the lower the scores in the HIT-6 and MIDAS scales, and the fewer the number of preventive drugs that have previously failed, the more likely the erenumab treatment will be effective. These are the effectiveness predictors that we have found in our study, together with the absence of MOH. Nevertheless, one unexpected predictive factor in our study was the simultaneous treatment with erenumab plus BoNT/A. This association was the strongest predictive factor of a good response and showed an excellent tolerability profile.

A huge number of real-world experiences analysing erenumab in migraine prevention are being published around the world [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. These experiences already include more than 2,000 patients with migraine, and, among them, we can find eleven one-centre studies (seven prospective [48, 53, 54, 56, 57, 59, 61] and four retrospectives [50,51,52, 62]) and five multicentre (four prospective [49, 55, 58, 60] and one retrospective [63]). Our registry includes the second largest sample of migraine patients treated with erenumab in a multicentric prospective registry. A published Italian study [55] included more patients, 372 patients, but this initiative was composed by a group of headache experts and it included only ten Italian centres, and nine of them were localized in the north of Italy. Our study is the official registry of the Spanish Neurological Society and includes 22 centres with homogeneous representation of the country. Moreover, the average number of prior preventive drug failures was 3–5 in the Italian study [55] and superior to 7 in ours, which means that our patients are more complex and treatment-refractory than the patients of the Italian study. Despite these differences, both the Italian study [55] and the other real-world experiences [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] conclude, like our registry, that erenumab is useful in the prevention of EM and CM and presents a good tolerability profile.

Erenumab has shown scarce adverse events in our registry (20%), like in the phase II [13,14,15,16,17,18] and phase III [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] clinical trials, meta-analysis [34,35,36,37,38,39], open-label extension studies [44,45,46] and real-world experiences [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Most of the adverse events were mild and transient in our study. Mild constipation, flu-like symptoms, transient pruritus at the injection site and fatigue were the only adverse events with incidences superior to 2%. We only collected two severe adverse events related to erenumab treatment (two skin rash after injection) that represent 0.9% of our patients, a similar figure to that of clinical trials and real-world experiences (1–3%) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62].

Regarding the initial dose of erenumab, we have not found any difference on effectiveness between them, unlike other studies [64]. On the other hand, the excellent tolerability pattern of the two doses of erenumab is already known and our study confirms it, despite the 140 mg dose showing a non-significant trend to be related to more adverse events than the dose of 70 mg.

This first report of the results of the MAB-MIG registry has some limitations. First: patients included are the most refractory ones of Spanish headache units and they were waiting the arrival of mAbs. For this reason, they do not exactly represent the Spanish real-world experience. Second: we present effectiveness and tolerability results at three months of therapy, a short follow-up. Finally, we have not analysed the comorbidities existence. Despite these limitations, MAB-MIG results have great strength because they are the first post-marketing results of erenumab collected by a neurology scientific society in 22 hospitals in one European country.

Conclusions

Our registry supports the tolerability and effectiveness of erenumab in the real-world clinical setting. In this way, one out three highly refractory migraine patients responded to erenumab with almost no relevant side effects.

Likewise, a high number of failures with previous preventive drugs, overuse of symptomatic medication and high degrees of disability are the main predictors of poor response. On the other hand, the concomitant use of BoNT/A plus erenumab seems to present an excellent tolerability profile, as it has already been proposed in several studies [65, 66] and is the strongest predictive factor of good response.

Availability of data and materials

Generated data in the MAB-MIG registry are not publicly available due to the Spanish law for the protection of personal data but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BoNT/A:

-

Botulinum toxin type A

- CGRP:

-

Calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CM:

-

Chronic migraine

- EM:

-

Episodic migraine

- HFEM:

-

High frequency episodic migraine

- HIT-6:

-

Headache impact test

- ICHD:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- IHS:

-

International Headache Society

- LFEM:

-

Low frequency episodic migraine

- mAbs:

-

Monoclonal antibodies

- MHD:

-

Monthly headache days

- MIDAS:

-

Migraine disability assessment questionnaire

- MMD:

-

Monthly migraine days

- MOH:

-

Medication overuse headache

- PGIC:

-

Patient global improvement change

- PROs:

-

Patient-reported outcomes

References

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, Lifting the Burden: The Global Campaign against Headache (2020) Migraine remains second among the world´s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain 21:137

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF, AMPP Advisory Group (2007) Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 68:343–349

Santos S, Pozo-Rosich P (2020) Headache clinical practice manual. Spanish Society of Neurology. Madrid: Ed. Luzon 5 SA

Tassorelli C, Diener HC, Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Ashina M et al (2018) Guidelines of the International Headache Society for controlled trials of preventive treatment of chronic migraine in adults. Cephalalgia 38:815–832

Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, Oster G (2012) Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract 12:541–549

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Chia J, Matthew N, Gillard P et al (2017) Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia 37:470–485

Lafata JE, Tunceli O, Cerghet M, Sharma KP, Lipton RB (2010) The use of migraine preventive medications among patients with and without migraine headaches. Cephalalgia 30:97–104

Ashina H, Schytz HW, Ashina M (2018) CGRP in human models of primary headaches. Cephalalgia 38:353–360

Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R (1988) Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann Neurol 23:193–196

Riesco N, Cernuda-Morollón E, Pascual J (2017) Neuropeptides as a marker for chronic headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 21:18

Cernuda-Morollón E, Martínez-Camblor P, Ramón C, Larrosa D, Serrano-Pertierra E, Pascual J (2014) CGRP and VIP levels as predictors of efficacy of Onabotulinumtoxin type A in chronic migraine. Headache 54:987–995

Hansen JM, Hauge AW, Olesen J, Ashina M (2010) Calcitonin gene-related peptide triggers migraine-like attacks in patients with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia 30:1179–1186

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Olesen J, Ashina M (2014) Safety and efficacy of ALD403, an antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of frequent episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, exploratory phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 13:1100–1107

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Spierings EL, Scherer JC, Sweeney SP, Grayzel DS (2014) Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol 13:885–892

Bigal ME, Dodick DW, Rapoport AM, Silberstein SD, Ma Y, Yang R et al (2015) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol 14:1081–1090

Bigal ME, Edvinsson L, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Spierings EL, Diener HC et al (2015) Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV-48125 for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol 14:1091–1100

Sun H, Dodick DW, Silberstein S, Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Ashina M et al (2016) Safety and efficacy of AMG 334 for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 15:382–390

Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Silberstein S, Goadsby PJ, Biondi D, Hirman J et al (2019) Eptinezumab for prevention of chronic migraine: a randomized phase 2b clinical trial. Cephalalgia 39:1075–1085

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T et al (2017) Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med 377:2113–2122

Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, Ossipov MH, Kim BK, Yang JY (2017) Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 38:1442–1454

Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, Broessner G, Bonner JH, Zhang F et al (2017) A controlled trial of Erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med 377:2123–2132

Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Lanteri-Minet M, Osipova V et al (2017) ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 38:1026–1037

Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Wen S, Hours-Zesiger P, Ferrari MD et al (2018) Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet 392:2280–2287

Skljarevski V, Oakes TM, Zhang Q, Ferguson MB, Martinez J, Camporeale A et al (2018) Effect of different doses of Galcanezumab vs placebo for episodic migraine prevention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 75:187–193

Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T et al (2018) Effect of Fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319:1999–2008

Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, Carter JN, Ailani J, Conley RR (2018) Evaluation of Galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 75:1080–1088

Silberstein SD, Kudrow D, Saper J, Janelidze M, Smith T, Dodick DW et al (2018) Eptinezumab results for the prevention of episodic migraine over one year in the PROMISE-1 (PRevention of migraine via intravenous Eptinezumab safety and efficacy-1) trial. Headache 58:1298

Detke HC, Goadsby PJ, Wang S, Friedman DI, Selzler KJ, Aurora SK (2018) Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: The randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled REGAIN study. Neurology 91:e2211–e2221

Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, Galic M, Cohen JM, Yang R et al (2019) Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 394:1030–1040

Silberstein SD, Cohen JM, Seminerio MJ, Yang R, Ashina S, Katsarava Z et al (2019) Erenumab in chronic migraine with medication overuse: subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Neurology 92:e2309–e2320

Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, Schaeffler BA, Biondi DM, Hirman J et al (2020) Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia 40:241–254

Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, Schaeffler BA, Biondi DM, Hirman J et al (2020) Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology 94:e1365–e1377

Charles A, Pozo-Rosich P (2019) Targeting calcitonin gene-related peptide: a new era in migraine therapy. Lancet 394:1765–1774

Hou M, Xing H, Cai Y, Li B, Wang X, Li P et al (2017) The effect and safety of monoclonal antibodies to calcitonin gene-related peptide and its receptor on migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Headache Pain 18:42

Hong P, Wu X, Liu Y (2017) Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody for preventive treatment of episodic migraine: a meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 154:74–78

Zhu Y, Liu Y, Zhao J, Han Q, Liu L, Shen X (2018) The efficacy and safety of calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody for episodic migraine: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci 39:2097–2106

Lattanzi S, Brigo F, Trinka E, Vernieri F, Corradetti T, Dobran M et al (2019) Erenumab for preventive treatment of migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. Drugs 79:417–431

Xu D, Chen D, Zhu LN, Tan G, Wang HJ, Zhang Y et al (2019) Safety and tolerability of calcitonin-gene-related peptide binding monoclonal antibodies for the prevention of episodic migraine - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cephalalgia 39:1164–1179

Deng H, Li GG, Nie H, Feng YY, Guo GY et al (2020) Efficacy and safety of calcitonin-gene-related peptide binding monoclonal antibodies for the preventive treatment of episodic migraine - an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 20:57

American Headache Society (2019) The American headache society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 59:1–18

Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, Reuter U, Terwindt G, Mitsikostas DD et al (2019) European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain 20:6

Santos-Lasaosa S, Belvís R, Cuadrado ML, Díaz-Insa S, Gago-Veiga A, Guerrero-Peral AL, Huerta M, Irimia P, Láinez JM, Latorre G, Leira R, Pascual J, Porta-Etessam J, Sánchez Del Río M, Viguera J, Pozo-Rosich P. (2019) Neurologia (Engl Ed). S0213-4853(19)30075-1

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2018) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 38:1–211

epper SJ, Ashina M, Reuter U, Brandes JL, Doležil D, Silberstein SD, Winner P, Zhang F, Cheng S, Mikol DD. (2020) Long-term safety and efficacy of erenumab in patients with chronic migraine: Results from a 52-week, open-label extension study. Cephalalgia. 40(6):543-553

Ashina M, Kudrow D, Reuter U, Dolezil D, Silberstein S, Tepper SJ et al (2019) Long-term tolerability and nonvascular safety of erenumab, a novel calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist for prevention of migraine: a pooled analysis of four placebo-controlled trials with long-term extensions. Cephalalgia 39:1798–1808

Ashina M, Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Silberstein S, Dodick D, Rippon GA et al (2019) Long-term safety and tolerability of erenumab: three-plus year results from a five-year open-label extension study in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 39:1455–1464

Robbins L, Phenicie B (2018) Early data on the 1st migraine-inhibiting CGRP. In: Practical pain management

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L (2019) Erenumab: from scientific evidence to clinical practice-the first Italian real-life data. Neurol Sci 40:177–179

Ornello R, Casalena A, Frattale I, Gabriele A, Affaitati G, Giamberardino MA et al (2020) Real-life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy. J Headache Pain 21:32

Robblee J, Devick KL, Mendez N, Potter J, Slonaker J, Starling AJ (2020) Real-world patient experience with erenumab for the preventive treatment of migraine. Headache 60:2014–2025

Kanaan S, Hettie G, Loder E, Burch R (2020) Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of erenumab: a retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia 40:1511–1522

Scheffler A, Messel O, Wurthmann S, Nsaka M, Kleinschnitz C, Glas M et al (2020) Erenumab in highly therapy-refractory migraine patients: first German real-world evidence. J Headache Pain 21:84

Lambru G, Hill B, Murphy M, Tylova I, Andreou AP (2020) A prospective real-world analysis of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine. J Headache Pain 21:61

Russo A, Silvestro M, Scotto di Clemente F, Trojsi F, Bisecco A, Bonavita S et al (2020) Multidimensional assessment of the effects of erenumab in chronic migraine patients with previous unsuccessful preventive treatments: a comprehensive real-world experience. J Headache Pain 21:69

Barbanti P, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Fofi L, Cevoli S, Colombo B et al (2021) Erenumab in the prevention of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine: Erenumab in Real Life in Italy (EARLY), the first Italian multicenter, prospective real-life study. Headache 61:363–372

Pensato U, Favoni V, Pascazio A, Benini M, Asioli GM, Merli E et al (2020) Erenumab efficacy in highly resistant chronic migraine: a real-life study. Neurol Sci 41:457–459

Disco C, Billo G, De Boni A, De Luca C, Perini F (2020) Efficacy of erenumab 70 mg in chronic migraine: Vicenza experience. Neurol Sci 41:479–480

Schiano di Cola F, Rao R, Caratozzolo S, Di Cesare M, Venturelli E, Balducci U et al (2020) Erenumab efficacy in chronic migraine and medication overuse: a real-life multicentric Italian observational study. Neurol Sci 41:489–490

Matteo E, Favoni V, Pascazio A, Pensato U, Benini M, Asioli GM et al (2020) Erenumab in 159 high frequency and chronic migraine patients: real-life results from the Bologna Headache Center. Neurol Sci 41:483–484

Cheng S, Jenkins B, Limberg N, Hutton E (2020) Erenumab in chronic migraine: an Australian experience. Headache 60:2555–2562

Ranieri A, Alfieri G, Napolitano M, Servillo G, Candelaresi P, Di Iorio W et al (2020) One year experience with erenumab: real-life data in 30 consecutive patients. Neurol Sci 41:505–506

Valle ED, Di Falco M, Mancioli A, Corbetta S, La Spina I et al (2020) Efficacy and safety of erenumab in the real-life setting of S. Antonio Abate Hospital’s Headache Center (Gallarate). Neurol Sci 41:465

Raffaelli B, Kalantzis R, Mecklenburg J, Overeem LH, Neeb L, Gendolla A et al (2020) Erenumab in chronic migraine patients who previously failed five first-line oral prophylactics and onabotulinumtoxinA: a dual-center retrospective observational study. Front Neurol 11:417

Ornello R, Tiseo C, Frattale I, Perrotta G, Marini C, Pistoia F et al (2019) The appropriate dosing of erenumab for migraine prevention after multiple preventive treatment failures: a critical appraisal. J Headache Pain 20:99

Armanious M, Khalil N, Lu Y, Jimenez-Sanders R (2021) Erenumab and onabotulinumtoxinA combination therapy for the prevention of intractable chronic migraine without aura: a retrospective analysis. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 35:1–6

Talbot J, Stuckey R, Crawford L, Weatherby S, Mullin S (2021) Improvements in pain, medication use and quality of life in onabotulinumtoxinA-resistant chronic migraine patients following erenumab treatment - real world outcomes. J Headache Pain 22:5

Acknowledgements

We thank Ignasi Gich for the statistical advice to analyse MAB-MIG registry. We also want to thank the hospital´s outpatient pharmacy and nursing staff for their participation and involvement in the therapy with CGRP mAbs.

Funding

We declare that we have not received any scholarship, nor grant, nor help to do the MAB-MIG registry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RB: Registry coordinator, Member of the Scientific Committee, Choice of variables and base design, Patient recruitment, Data management, Statistical analysis, Redaction of the paper. PI. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. PPR. Member of the Scientific Committee, Choice of variables and base design, Patient recruitment, Data management, Statistical analysis, Redaction of the paper. CGO. Member of the Scientific Committee, Choice of variables and base design, Patient recruitment, Data management, Statistical analysis, Redaction of the paper. JV. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. BS. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. FM. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. MSR. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. IB. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. AO. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. EC. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. AGC. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. MAW. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. CJ. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. TO. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. DE. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. JDT. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. NM. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. GL. Member of the Scientific Committee, Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. MTF. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. AL. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. RL. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. CT. Patient recruitment, Redaction of the paper. RL. Member of the Scientific Committee, Choice of variables and base design, Patient recruitment, Data management, Statistical analysis, Redaction of the paper. SS. Registry coordinator, Member of the Scientific Committee, Choice of variables and base design, Patient recruitment, Data management, Statistical analysis, Redaction of the paper. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

MAB-MIG was classified as a low-intervention clinical trial by the Spanish Medicines Agency and Medical Devices and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Investigation with Medicines of the Health Area of Valladolid, Spain (PI 20–1790).

Consent for publication

Authors consent the publication of the paper MAB-MIG: REGISTRY OF THE SPANISH NEUROLOGICAL SOCIETY OF ERENUMAB FOR MIGRAINE PREVENTION. THREE-MONTHS RESULTS in The Journal of Headache and Pain.

Competing interests

Within the prior 24 months, RB, PI, PP-R, CG-O, and MSDR have received honoraria as consultant and/or speaker for Eli-Lilly, Novartis, Teva, and Allergan/Abbvie.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Belvís, R., Irimia, P., Pozo-Rosich, P. et al. MAB-MIG: registry of the spanish neurological society of erenumab for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain 22, 74 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01267-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01267-x