Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has already caused 6 million deaths worldwide. While asymptomatic individuals are responsible of many potential transmissions, the difficulty to identify and isolate them at the high peak of infection constitutes still a real challenge. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 provokes severe vascular damage and thromboembolic events in critical COVID-19 patients, deriving in many related deaths and long-hauler symptoms. Understanding how these processes are triggered as well as the potential long-term sequelae, even in asymptomatic individuals, becomes essential.

Methods

We have evaluated, by application of a proteomics-based quantitative approach, the effect of serum from COVID-19 asymptomatic individuals over circulating angiogenic cells (CACs). Healthy CACs were incubated ex-vivo with the serum of either COVID-19 negative (PCR −/IgG −, n:8) or COVID-19 positive asymptomatic donors, at different infective stages: PCR +/IgG − (n:8) and PCR −/IgG + (n:8). Also, a label free quantitative approach was applied to identify and quantify protein differences between these serums. Finally, machine learning algorithms were applied to validate the differential protein patterns in CACs.

Results

Our results confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 promotes changes at the protein level in the serum of infected asymptomatic individuals, mainly correlated with altered coagulation and inflammatory processes (Fibrinogen, Von Willebrand Factor, Thrombospondin-1). At the cellular level, proteins like ICAM-1, TLR2 or Ezrin/Radixin were only up-regulated in CACs treated with the serum of asymptomatic patients at the highest peak of infection (PCR + /IgG −), but not with the serum of PCR −/IgG + individuals. Several proteins stood out as significantly discriminating markers in CACs in response to PCR or IgG + serums. Many of these proteins particiArticle title: Kindly check and confirm the edit made in the article title.pate in the initial endothelial response against the virus.

Conclusions

The ex vivo incubation of CACs with the serum of asymptomatic COVID-19 donors at different stages of infection promoted protein changes representative of the endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory response after viral infection, together with activation of the coagulation process. The current approach constitutes an optimal model to study the response of vascular cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and an alternative platform to test potential inhibitors targeting either the virus entry pathway or the immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the pathogen responsible of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), declared as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization. SARS-CoV-2 was identified for the first time in hospitalized patients with pneumonia in Wuhan (China) in December 2019, as an RNA virus of coronaviruses family (Zhu et al. 2020). Up to date (March 3, 2022), COVID-19 has provoked 6 million deaths worldwide (www.covid19.who.int), significantly affecting public health, the economics and society (Shipton et al. 2021; Bambra et al. 2020). Asymptomatic COVID-19 cases are responsible for many transmissions, which constitutes a real challenge to control the pandemic (Kronbichler et al. 2020). Approximately half of SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals are symptomatic at the time of testing, as determined by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Alene et al. 2021; Ra et al. 2021). This makes their detection quite difficult, since most of these individuals don’t seek testing and/or medical assistance and continue with their daily routine, contributing to rapid spread of COVID-19 (Gao et al. 2021). The identification of alternative markers (apart from physical symptoms or qPCR analysis) could significantly contribute to detect all potential SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals. Besides, little is known about the potential sequelae of SARS-Cov-2 over asymptomatic patients, and also how these initially “mild” infected people might become long-haulers at the long term (Huang et al. 2021).

Manifestations of COVID-19 are mostly respiratory; however, COVID-19 can also negatively affect extra-pulmonary systems (Snell 2021), including the heart and systemic vasculature (Klok et al. 2020; Marone and Rinaldi 2020; Huang et al. 2020). Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 infection has been linked to cardiovascular alterations (arrhythmias, ischemic heart disease or cardiomyopathies), mainly associated to coagulation abnormalities and endothelial damage, leading to thrombosis (Alvarado-Moreno et al. 2021; Thachil et al. 2020). COVID-19 enhances endothelial dysfunction, which not only involves oxidative stress, dysregulation of vascular tone or inflammatory response from the vascular wall (Jin et al. 2020), but also promotes the mobilization and recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (Alvarado-Moreno et al. 2021; Mancuso et al. 2020), key cells involved in vascular repair (Zhang et al. 2014). Remarkably, the levels of circulating EPCs are significantly increased in the blood of COVID-19 patients compared with healthy controls (Mancuso et al. 2020; Guervilly et al. 2020), even three months after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Poyatos et al. 2021).

EPCs were first isolated from peripheral blood by Asahara et al., being defined as CD34 + cells that could differentiate in vitro to endothelial cells (ECs) (Asahara et al. 1997). Currently, EPCs are classified in two main sub-populations: early EPCs, also known as circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) and late EPCs or endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs). CACs have a hematopoietic like phenotype and they exert their regenerative activity through paracrine mechanisms while ECFCs have an endothelial phenotype and can differentiate into mature ECs, participating directly in blood vessels formation (Hur et al. 2004; Medina et al. 2017). SARS-CoV-2 infection could negatively affect the repairing properties of EPCs, interfering with the normal functioning of the cardiovascular system. However, not many studies have been done on how EPCs behave in COVID-19 patients.

A better understanding of the initial stages in which SARS-CoV-2 affects the endothelium, even in asymptomatic individuals, becomes crucial in order to predict or prevent unwanted secondary effects, and the risk of suffering from severe complications. In the current study, we have evaluated, by application of a mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitative approach, the proteomic changes taking place in healthy CACs in response to the differential factors present in the serum of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Study population

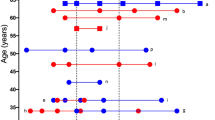

The study was conducted in asymptomatic donors recruited at the National Paraplegic Hospital (SESCAM), Toledo, Spain during April–May 2020. They were all workers of this hospital. A graphical representation of some characteristics registered for the study population is shown in Fig. 1A–C.

Study population characteristics and schematic representation of the experimental assay. A graphical representation of the donors’ characteristics is shown, including A Gender, B age and C Cardiovascular (CV) risks reported for each group. D Schematic representation of the infective stage of asymptomatic individuals at the time of serum extraction. Individuals were classified as COVID-19 negative (PCR −/IgG −, n:29), or COVID-19 positive, at the peak of infection (PCR + /IgG −, n:8) or after the infective peak (PCR −/IgG +, n:27). E CACs were incubated with the serum of COVID-19 negative donors, or with the serum of COVID-19 PCR + or COVID-19-IgG + asymptomatic patients

Serum sample collection and tests performed for COVID-19 diagnostic

Briefly, peripheral blood samples were collected using serum separator tubes (SSTTM II advance, BD Vacutainer®), centrifuged (4000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and stored at − 80 °C.

A SARS-CoV-2 qPCR analysis from nasopharyngeal samples was performed to determine the positive or negative status of the donors. Also, an ELISA assay testing for specific IgG and IgM antibodies (IME00136 and IME00137; Erba Mannheim) was performed with the serum previously collected. With all this information, donors were classified into three different groups: healthy donors with negative qPCR and antibody’s analysis test (Neg, n:29), asymptomatic patients with positive qPCR test for SARS-CoV-2 at blood extraction time (PCR + , n:8) and asymptomatic patients with positive IgG antibodies (IgG + , n:27) at the time of blood extraction (Fig. 1D).

CACs isolation and culture

CACs were isolated from buffy coats from two healthy donors provided by the Andalusian Biobank Network (Decree 1/2013). Briefly, CACs were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and cultured as previously described (Eslava-Alcon et al. 2020; Vega et al. 2017). PBMCs were isolated and plated in fibronectin coated plates (10 μg/ml) and incubated in EBM-2 media plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Single Quots growth factors (Lonza). Non-adherent cells were discarded after four days and attached cells were allowed to grow in fresh media until day 7, when experimental assays were performed. CACs were characterized by flow cytometry assay, as described (Eslava-Alcon et al. 2020).

CACs incubation ex vivo with patients’ serum

CACs (aprox. 1 million cells per group) were washed several times with PBS 1X, to discard any remaining traces of FBS from the initial conditioned media, and then incubated 24 h (37 °C, 10% CO2) with EBM-2 medium containing 10% serum of the Neg (CACs + Neg), PCR + /IgG − (CACs + PCR) or PCR −/IgG + groups (CACs + IgG), n:8 per group (Fig. 1E). After that, cells were collected using Trypsin–EDTA 1X (X0930-100; Biowest), centrifuged and washed once with PBS 1X, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before their storage at -80 ºC.

Proteomic analysis

A label free quantitative (LFQ) MS approach was applied in order to identify differential protein levels between serum samples of asymptomatic donors (Neg n:29; PCR + n:8; IgG + n:27). Also, the protein changes in CACs after the incubation with the different sets of serum samples (CACs + Neg, n:8; CACs + PCR, n:8; CACs + IgG, n:8) were analyzed following the same LFQ approach.

Serum samples (10 μl) were supplemented with protease inhibitors (04693132001; Roche) and precipitated with acetone, over-night, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm, 25 min and the pellet resuspended in 8 M urea. Similarly, the cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of 8 M urea containing protease inhibitors (04693132001; Roche) for protein extraction and further proteomic analysis. For all samples, protein amount was quantified with the Qubit Fluorometric system (ThermoFisher Scientific) following manufacturer´s guidelines, and 50 µg of proteins in 8 M urea per sample were reduced (10 mM Dithiothreitol) and alkylated (50 mM Iodoacetamide). Samples were diluted four times with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and digested with Trypsin/LysC (V5073; Promega) (enzyme/substrate ratio 1:50) at 37 °C overnight. Finally, digestion was quenched with 0.1% TFA before peptide purification with C18 micro-columns, as described (Palmisano et al. 2010), and eluates were dried with a speed-vac system.

Liquid chromatography

A nanoElute high pressure nanoflow system (Bruker Daltonics) was connected to the timsTOF Pro, an ion-mobility quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) that uses the parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (PASEF) acquisition method. Peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (FA) up to a final concentration of 100 ng/μl and 200 ng were delivered to a Thermo Trap Cartridge (5 mm) column, and a reverse phase analytical column (25 cm × 75 um id IonOptics 25 cm, Thermo). Liquid chromatography was performed at 50ºC and peptides were separated on the analytical column using a 60 min gradient with buffers A (0.1% FA) and B (0.1% FA, Acetonitrile). For all samples, the TIMS-TOF Pro instrument was operated in data dependent acquisition (DDA) mode.

Data processing

Raw files were processed with MaxQuant (v 1.6.0.1), searching against a human protein database (Human UniProt) supplemented with contaminants. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines, oxidation of methionine and protein N-term acetylation were set as variable modifications. Minimal peptide length was set to 7 amino acids and a maximum of two tryptic missed-cleavages were allowed. Results were filtered at 1% FDR (peptide and protein level) and only proteins with at least two peptides identified were considered for further analysis. LFQ was done with match between runs (match window of 0.7 min and alignment window of 20 min). Afterwards, the “proteinGroup.txt” file was loaded in Perseus (v1.6.0.2) for further statistical analysis.

Proteins were considered as differentially expressed between groups when p-value < 0.05 and ratio > 1.5 (up-regulated) or ratio < 0.6 (down-regulated). Data processing was done using Venny v2.1 (Venn’s diagram), Perseus (hierarchical cluster), String (www.string-db.org), Enrichr (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr), Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA, Qiagen), Reactome (functional roles of proteins, www.reactome.org) and PINA v3 platform (protein interaction network analysis, www.omics.bjcancer.org/pina).

Statistical analysis and machine learning

Protein quantification and statistics were obtained using MaxQuant (Tyanova et al. 2016a) and Perseus 1.6.15.0 (Tyanova et al. 2016b) software. Reverse database hits and contaminants were removed before performing a Student's T-test analysis with a multiple hypothesis correction of p-values (1% FDR). Differences were considered statistically significant when p-value < 0.05. Protein changes were confirmed with GraphPad Prism 9 software, and data were presented with box and plots graphs representing median, min and max value and showing all points. Also, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for differentially expressed proteins by plotting sensitivity (%) against 100%—specificity (%), indicating the area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, we investigated the feasibility to perform two types of classification schemes based on protein levels using machine learning techniques: (a) a binary classification to discriminate between CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg samples; and (b) a ternary classification into CACs treated with the serum from PCR + , IgG + asymptomatic and negative donors. Several supervised learning methods were applied in combination with a supervised attribute filter used to select features evaluating the worth of an attribute with a specified classifier (Deeb et al. 2015; Shi et al. 2021). Proteins were ranked according to their individual evaluations and the best 20 ranked ones were selected in each case.

Considering that complex models in small datasets limit generalization, low complexity models were used. In the case of the proposed ternary classification, performance metrics of linear support vector machines (SVM), Naïve Bayes (NB) and Random Forest algorithms were compared. For the binary classification, we compared linear SVM, NB, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO). In all cases, we combined the model-based prediction with feature selection to optimize the performance of the classifier and to identify strongly discriminative proteins. Accuracy was used as evaluation measure in the feature selection process. Both, the model training, and the feature selection, were done in a fivefold cross-validation procedure. The quality of classification was assessed using several parameters: accuracy, recall, true and false positive rate, and the area under the ROC curve. MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, USA) and WEKA data mining software were used for building the models.

Results

Proteomic evaluation of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients’ serum

In total, 191 proteins were identified in serum by proteomic analysis (Additional file 1: Table S2). Among them, several proteins were altered in asymptomatic patients (PCR + /IgG − and PCR −/IgG + at the time of serum extraction), compared to COVID-19 negative subjects (Fig. 2). The differential protein patterns seen between groups are shown in a heat-map cluster (Fig. 2A). Proteins like TTR, SERPINA1, FGA, THBS1 or CFHR1 were up-regulated in the serum of PCR + and IgG + donors compared to negative individuals, showing significant differences between them (Fig. 2B). Others, like ECM1 or APOH, were down-regulated in PCR + and IgG + serums compared to negative controls. In some cases, like APOD or Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP), the levels increased in PCR + donors while decreased (still higher than in controls) in the serum of IgG + individuals. These proteins participate, among others, in the coagulation cascade process, platelet degranulation (APOH, ECM1, SERPINA1), or regulation of endothelial cell migration (APOH, ECM1, THBS1) and proliferation (AGT, APOD, HGFAC, FGA, SERPINA1) (Fig. 2C). Also, according to IPA analysis, some of them have been associated with viral infection (APOD, APOH, SERPINA1), severe COVID-19 (APOD, APOH, PCYOX1), or leukocyte migration (APOD, IGHV3-13, IGHV3-23, SERPINA1, IGLC7, IGLV3-21).

Proteins altered in asymptomatic patients’ serum and functional network. A Hierarchical clustering comparing the proteins patterns of the three groups analyzed. B Graphical representation of the label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities registered for proteins altered in the serum of COVID-19 PCR + (n:8) and COVID-19 IgG + asymptomatic patients (n:27) compared to COVID-19 negative donors (n:29). Differences were considered significant when p-values < 0.05. *p-value < 0.05, *p-value < 0.01, *p-value < 0.001. C Functional network, obtained with String on-line platform, highlighting the interactions detected between the serum proteins altered in the groups analyzed. Some of the most relevant functions identified for these proteins are represented

Molecular changes in CACs after incubation with COVID-19 serum samples

In total, 1438 proteins were identified in CACs incubated with the serum of COVID-19 negative (CACs + Neg), PCR + (CACs + PCR) and IgG + (CACs + IgG) asymptomatic donors (Additional file 1: Table S3). Furthermore, according to the LFQ analysis (Fig. 3A, B), several proteins were up-regulated in CACs + PCR (19 proteins) or CACs + IgG (3 proteins) compared to CACs + Neg controls (Fig. 3C). Also, other proteins were down-regulated (37 in CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg and 30 in CACs + IgG vs CACs + Neg respectively) (Fig. 3C), while common alterations in both comparisons were identified too (Fig. 3D). A hierarchical classification of differentially expressed proteins indicated that the protein profiles of CACs in response to PCR + or IgG + serum were more similar between themselves than in CACs + Neg controls (Fig. 3E).

Proteomic changes in CACs in response to the serum of COVID-19 asymptomatic patients. Volcano plots representing proteins up- (red) or down- (green) regulated between CACs treated with A the serum of COVID-19 PCR + vs Negative donors (CACs + PCR), or B the serum of IgG + (CACs + IgG) vs COVID-19 negative donors (CACs + Neg). C Schematic representation of the number of proteins up- (red) or down- regulated (green) in CACs + PCR or CACs + IgG compared to CACs + Neg controls. D Venn’s diagram including the number of proteins up- or down-regulated, common or exclusive in CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg, or in CACs + IgG vs CAC + Neg. E Hierarchical cluster representing the differential protein profiles for CACs + PCR, CACs + IgG or CACs + Neg

Proteins like Toll like receptor 2 (TLR2), Radixin, Matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP14), Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), CD44, GLUL, RAB10 or FLNA were significantly up-regulated in CACs + PCR, but the levels decreased in CACs + IgG. Similarly, proteins like Stabilin-1 (STAB1) or Myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen (MNDA), were down-regulated in the CACs + PCR group while recovered in CACs + IgG + serums. Other proteins (COPZ1, RPS23, CAPN2, NCF1) were down-regulated in both, CACs + PCR and CACs + IgG compared to CACs + Neg controls. The most relevant changes are shown in Fig. 4.

Proteins altered in CACs incubated with asymptomatic patients’ serum compared with negatives and functional network. A Graphical representation of the label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities registered for several proteins altered in CACs + PCR (n:8) and CACs + IgG (n:8) compared to CACs + Neg controls (n:8). Differences were considered significant when p-values < 0.05. *p-value < 0.05, *p-value < 0.01, *p-value < 0.001. B Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of HSPA5, STAB1, RAB10 and TMP3 proteins in asymptomatic COVID-19 patients with area under curve (AUC). C Naïve Bayes classifier

Some of these differentially expressed proteins were clearly discriminative for CACs in response to PCR + vs Negative serum or between CACs + IgG vs CACs + Neg groups, as indicated by the high AUCs values (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, several proteins stood out as result of applying machine learning algorithms (Additional file 1: Tables S4–6), including MNDA, STAB1, TLR2 or the Heat shock protein family A member 5 (HSPA5), among others. The built linear SVM, NB, PLS-DA, and LASSO models presented an accuracy of 1.00, achieving a maximum performance when classifying CACs + PCR and CACs + Neg treatments. Likewise, significant results were obtained with all these models (Table 1) when a ternary classification was applied to discriminate between CACs + PCR, CACs + IgG or CACs + Neg conditions. The NB classifier provided the best results, with an accuracy of 0.93 and a ROC area of 0.96 (Fig. 4C).

Functional classification of proteins differentially expressed in CACs after incubation with COVID-19 serum samples

The functional classification of differentially expressed proteins highlighted several major pathways altered in CACs + PCR (Fig. 5A). Moreover, according to IPA functional classification, several proteins altered in CACs in response to the PCR + serum have been previously linked to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or viral infection (Fig. 5B), together with leukocyte extravasation (Fig. 5C), among others. Similarly, some proteins altered in CACs + IgG were associated to coronavirus replication and its pathogenesis pathway (Fig. 4D). The most relevant functions of proteins altered in CACs + PCR cells are shown in Table 2.

Functional classification of proteomic changes in CACs treated with the serum of PCR + vs Neg donors. A Altered pathways related with up- (red) and down- (green) regulated proteins in CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg. B Ingenuity (IPA) functional network with proteins up- (red) or down-regulated (green) in CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg, correlated with viral infection and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), among others. C IPA graphical representation of proteins altered in CACs incubated with the serum of COVID-19 PCR + patients, compared to negative controls, participating in leukocyte extravasation signaling. D Proteins altered in CACs + IgG vs CACs + Neg related to viral pathogenesis and replication

Interaction networks between serum and CACs altered proteins

An in-silico interaction network analysis was performed in order to find correlations between the proteins altered in the serum of COVID-19 asymptomatic donors and the protein changes in CACs in response to these factors (Fig. 6B). The networks found were mainly associated with platelet activation and signaling, as well as with extracellular matrix and activation of immune system in CACs. Several altered proteins in the serum of COVID-19 positive asymptomatic donors (FGA, SERPINA1, THBS1) and moreover, in CACs treated with these serum factors (HSPA5, FN1), have been associated with platelet aggregation and coagulation problems (Fig. 6C).

Interactions between proteins altered in serum and CACs samples. A Venn’s diagram including the number of proteins up- or down-regulated, common or exclusive in serum samples and CACs + PCR vs CACs + Neg and CACs + IgG vs CACs + Neg comparisons. B An in-silico analysis evaluating the potential interactions between altered proteins in the serum of COVID-19 asymptomatic donors (PCR + and IgG +) and the proteins altered in healthy CACs in response to those serums was performed with PINA v3 on-line platform. C One of the most representative functions found between the interactions found between both sets (serum and CACs) of altered proteins was platelet activation, including platelet aggregation and degranulation. Figure obtained with Reactome

Discussion

COVID-19 asymptomatic individuals or with mild symptoms present similar loads of SARS-CoV-2 virus in respiratory samples than symptomatic patients (Ra et al. 2021; You et al. 2021), representing a population that highly increases the risk of viral transmission due to the difficulties to identify and “isolate” them at the time of infection (Kronbichler et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2021). In addition, despite extraordinary research progress in the last two years, much is still unknown about the real impact of SARS-CoV-2 over the organism and the long-term consequences of such infection, even in asymptomatic individuals. In particular, the interaction of this virus with the cardiovascular system is still largely unknown.

To date, different studies have extensively analyzed the proteomic changes in serum, plasma or even urine from severe, critical, moderate or mild COVID-19 patients, in an attempt to identify potential signatures of the different stages of the disease (D’Alessandro et al. 2020; Messner et al. 2020; McArdle et al. 2021). However, not many studies have evaluated what happens in asymptomatic people. Herein, we have identified serum proteomic changes in asymptomatic individuals depending on the time of infection, including proteins up- or downregulated only at the highest infective peak (PCR + /IgG − in serum). These data corroborate that SARS-CoV-2 causes molecular alterations even in total or partial absence of classical symptoms. Many of the protein changes seen, mainly in PCR + serums, correlated to viral infection, platelet degranulation and leukocyte migration. These processes have already been described in severe COVID-19 patients (Shen et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2020).

Among them, CETP was up-regulated in the serum of asymptomatic individuals, as previously seen in COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms (Liu et al. 2021), while in the serum of critical patients this protein appeared down-regulated (Shu et al. 2020). CETP mediates lipid exchange (Satoh et al. 2016), but it also inhibits prolonged inflammation. Thus, CETP upregulation might correlate with the alteration of lipids after viral infection (membrane fusion, vesicles, etc.) (Abu-Farha et al. 2020), or even contribute to the lack of symptomatology in these patients (Shu et al. 2020). Similarly, plasma phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) was up-regulated mainly in PCR + asymptomatic individuals. PLTP regulates lipoprotein metabolism, as well as inflammation and immune response, affecting Th1/Th2 polarization via modulation of IL18 expression (Desrumaux et al. 2016). Remarkably, these and other serum proteins related to lipid metabolism were previously seen in SARS-CoV patients, presenting an altered lipid and glucose metabolism even 12 years after infection (Wu et al. 2017). Further studies should evaluate the exact mechanisms by which coronaviruses affect lipid and glucose metabolism (Keihanian and Bigdelu 2020), since they could provide new insights regarding the adverse chronic cardiovascular complications.

Angiotensinogen (AGT) was also up-regulated in the serum of asymptomatic donors. AGT interacts with angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), one of the main receptors responsible of SARS-CoV-2 entrance into the host cells which has been associated to COVID-19 cardiovascular complications (Wang et al. 2020; Wicik et al. 2020). In addition, other proteins up-regulated were thrombospondin (THBS1), fibrinogen α (FGA) or Von Willebrand factor (vWF), normally secreted by platelets during the degranulation process (Mehta and Yusuf 2003). These three proteins were already identified as procoagulant and thrombo-inflammatory markers in severe COVID-19 patients (Liu et al. 2021; Wool and Miller 2021; Zamanian-Azodi et al. 2021; Ward et al. 2021), but our data suggest that they are also altered at the peak of infection even in absence of symptoms. Since up-regulation of proteins like vWF correlates with inflammation, leaving the endothelium in a prothrombotic state (Ladikou et al. 2020; Escher et al. 2020), the potential long-term consequences of such endothelial damage in asymptomatic people should be tracked.

With this in mind, we next addressed whether the serum of asymptomatic COVID-19 individuals could affect basal endothelial cell function, by evaluating the protein changes taking place in CACs. Recent studies have reported an up-regulation of circulating EPCs levels even three months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, pointing them as vascular injury markers (Nizzoli et al. 2020). Thus, the effect of viral infection over these cells might help to explain potential cardiovascular secondary effects (Poyatos et al. 2021). Remarkably, many of the proteins altered in CACs incubated ex vivo with the serums of asymptomatic donors have been previously associated with viral infection, infection by RNA virus and SARS, but also to ECs movement or proliferation, and endothelial dysfunction. Besides, the alteration of proteins related to leukocyte extravasation and movement in CACs exposed to the serum of PCR + people, corroborates the activation of the immune process in these cells (Eslava-Alcon et al. 2020; Beltrán-Camacho et al. 2021; Medina et al. 2011). In response to pro-inflammatory stimuli such as viral infection, circulating EPCs initiate weak cell–cell interactions with the endothelium, promoting the expression of adhesion molecules such as E-selectin or ICAM-1 by these cells, which also promotes vascular permeability, EPCs adhesion and trans-endothelial migration (Krenning et al. 2009), as well as leukocyte recruitment (Othumpangat et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2020; Dai et al. 2008). Interestingly, ICAM-1 appeared up-regulated in CACs + PCR cells, but returned to basal levels in CACs + IgG. Elevated levels of ICAM-1 have been associated with severe endothelial dysfunction in severe COVID-19 patients (Nagashima et al. 2020; Tong et al. 2020). Also, the number of ICAM-1 + circulating EPCs appeared significantly increased in convalescent COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls (Chioh et al. 2021). Thus, ICAM-1 levels might be indicative of the patient’s progression towards a worse condition or a prompt recovery without major consequences, at least at the short term. Similarly, MMP14 was only up-regulated in CACs + PCR cells. MMP14 promotes LDL receptors shedding (Alabi et al. 2021), and it also participates in tissue remodeling by degrading several extracellular matrix components (collagen, gelatin, fibronectin, etc.), which is usually associated to inflammation (Xia et al. 2021; Hwang et al. 2004). Overall, MMP14 may regulate the infiltration and migration of inflammatory precursor cells under arterial inflammation (Ries et al. 2007).

CD44, receptor for hyaluronic acid (HA) in adult ECs and CACs, was also up-regulated in CACs + PCR cells, in agreement with recent findings reporting high circulating HA levels in COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls (Queisser et al. 2021). Similarly, heparin sulfate levels increased in HUVECs incubated with the plasma of COVID-19 patients, which was associated with endothelial glycocalyx shedding and degradation (Potje et al. 2021). Indeed, the glycocalyx becomes significantly damaged in severe COVID-19 patients, correlating with vascular damage in these patients (Queisser et al. 2021; Yamaoka-Tojo 2020; Teuwen et al. 2020). Finally, the incubation of human lung microvascular ECs with HA isolated from the plasma of COVID-19 patients, promoted endothelial barrier dysfunction in a CD44-depedent manner (Queisser et al. 2021).

Radixin was also over-expressed only in CACs + PCR. This protein shares 70% of the sequence with Ezrin, which appears to interact with the S spike protein of SARS-CoV, reducing viral entry (Millet et al. 2012), while in other cases like the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) Erzin enhances viral infectivity (Roy et al. 2014; Gadanec et al. 2021). Like Ezrin, Radixin might be exerting similar roles by modulating viral entry, although further studies should confirm such hypothesis.

Machine learning algorithms reported a list of proteins highly discriminating between the three groups compared (CACs + PCR, CACs + IgG or CACs + Neg). Among them, TLR2, up-regulated only in CACs + PCR, constitutes a cell surface innate immune sensor that can recognize several viral proteins upon infection (Oliveira-Nascimento et al. 2012), including the SARS-CoV-2 protein (Zheng et al. 2021). TLR2 activation in response to the SARS-CoV-2 E-protein promotes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and INF-γ in vivo and in vitro, in both human and mice cells. Interestingly, the administration of TLR2 inhibitors to infected mice might protect against SARS-CoV-2 by impairing the release of cytokines (IL6, MCP1 or CXCL10) necessary for the development of the disease (Zheng et al. 2021; Sariol and Perlman 2021). Remarkably, TLR2 decreased significantly to basal levels in CACs + IgG. Thus, the blockade of TLR2 might prevent the progression of the disease towards a more severe stage. Different clinical trials using TLR-antagonists (M5049, MMG11, CuCpt22, hydroxychloroquine sulfate, imiquimod, etc.) are currently evaluating this therapeutic strategy (Gadanec et al. 2021; Patra et al. 2021; Grabowski et al. 2020).

The cell-surface receptor HSPA5, up-regulated mainly in CACs + PCR, has been proposed as an additional receptor for SARS-CoV-2 attachment and entry, together with ACE2, susceptible to viral recognition through the substrate-binding domain (Ha et al. 2020; Chu et al. 2018). Indeed, HSPA5 inhibitors interfere with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Palmeira et al. 2020), corroborating this hypothesis, while HSPA5 levels might predispose to a severe progression and outcome of COVID-19 in patients with older age, obesity, and diabetes (Shin et al. 2021).

MNDA was one of the most discriminating proteins highlighted by the predictive approaches. MNDA is required for INFα production from human blood cells in response to viruses (Gu et al. 2022). MNDA down-regulation in CAC + PCR might reflect down-regulation of INFα, a powerful antiviral factor, in an attempt of SARS-CoV-2 to endorse its own propagation and infectability (Gu et al. 2022). The application of IFNα therapy to COVID-19 patients resulted in accelerated viral clearance from the upper airways and in a reduction of the inflammatory biomarkers IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) (Zhou et al. 2020). The fact that the MNDA went back to “normal” levels in CACs treated with IgG + serums could be indicative of cells overcoming the anti-viral blockade and cell post-infection recovery. Future studies should validate whether MNDA contributes indeed to the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

Finally, the interactions detected between the altered serum factors and the protein changes in CACs correlated with platelet activation, degranulation and an activation of the coagulation cascade. Noteworthy, EPCs are known to modulate platelet’s function and they also seem to limit thrombogenic events by supporting vascular repair of injured areas (Li and Li 2016; Abou-Saleh et al. 2009). Given the few interactions found with this in silico approach, the changes in CACs might be promoted by additional serum proteins, not identified herein, or even by other molecules such as microRNA or exosomes present in serum after COVID-19 infection.

Several limitations of this study should be addressed, such as the fact that serum samples were collected at the early period of the pandemic, and the number of samples collected was limited. Furthermore, donors were recruited prior vaccination started, so the potential effect that vaccines could have over the endothelial response should be also evaluated in future assays. Similarly, CACs were obtained from two healthy donors from whom no information was provided due to data protection assignments. Future studies may determine whether the response seen in our study would be different depending on the “endothelial” donors’ profile (healthy vs individuals with certain pathologies).

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate that the ex-vivo incubation of CACs with the serum from COVID-19 asymptomatic patients promoted changes that resembled the effects associated to SARS-CoV-2 infection (inflammatory response, ECM disruption and vascular damage, among others). Remarkably, such processes are currently considered as the primary causes of COVID-19 related coagulopathy. Therefore, our model has proven to be effective to evaluate the effect of SARS-CoV-2 at the cellular level. The protein changes detected were different depending on the disease stage, when cells were exposed to serum of PCR + donors (at the highest peak of infection) or the serum of IgG + /PCR − patients that had already overcome the disease with no apparent symptoms. Some of the proteins identified here, such as TLR2, ICAM-1, CD44, HSPA5 or MNDA, might be considered as potential targets to inhibit the direct or indirect effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the endothelium and the vascular system. Further studies should evaluate whether the continuous alteration of these proteins correlates with the individual’s progression to a more severe condition or even with long-hauler sequelae or, on the contrary, their modulation could help to overcome the disease hopefully without major consequences.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting the findings of this study have been provided within the article, together with online additional files. Also, proteomic results have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via PRIDE partner repository (Perez-Riverol et al. 2019) (PXD030860).

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2

- AGT:

-

Angiotensinogen

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CETP:

-

Cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CACs:

-

Circulating angiogenic cells

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ECs:

-

Endothelial cells

- ECFCs:

-

Endothelial colony-forming cells

- EPCs:

-

Endothelial progenitor cells

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FGA:

-

Fibrinogen α

- HIV-1:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus-1

- HA:

-

Hyaluronic acid

- ICAM-1:

-

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- LFQ:

-

Label free quantitative

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- MS:

-

Mass spectrometry

- MMP14:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase 14

- NB:

-

Naïve Bayes

- PLS-DA:

-

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PLTP:

-

Plasma phospholipid transfer protein

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SVM:

-

Support vector machines

- THBS1:

-

Thrombospondin 1

- TLR2:

-

Toll like receptor 2

- vWF:

-

Von Willebrand factor

References

Abou-Saleh H, Yacoub D, Theoret JF, Gillis MA, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells bind and inhibit platelet function and thrombus formation. Circulation. 2009;120(22):2230–9.

Abu-Farha M, Thanaraj TA, Qaddoumi MG, Hashem A, et al. The role of lipid metabolism in COVID-19 virus infection and as a drug target. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(10):3544.

Alabi A, Xia XD, Gu HM, Wang F, et al. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase promotes LDL receptor shedding and accelerates the development of atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1889.

Alene M, Yismaw L, Assemie MA, Ketema DB, et al. Magnitude of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases throughout the course of infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0249090.

Alvarado-Moreno JA, Davila-Moreno J, Dominguez-Reyes V, Arreola-Diaz R, et al. Morphological and functional alterations in endothelial colony-forming cells from recovered COVID-19 patients. Thromb Res. 2021;206:55–9.

Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275(5302):964–7.

Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(11):964–8.

Beltrán-Camacho L, Jiménez-Palomares M, Sanchez-Gomar I, Rosal-Vela A, et al. Long term response to circulating angiogenic cells, unstimulated or atherosclerotic pre-conditioned, in critical limb ischemic mice. Biomedicines. 2021;9(9):1147.

Chioh FW, Fong SW, Young BE, Wu KX, et al. Convalescent COVID-19 patients are susceptible to endothelial dysfunction due to persistent immune activation. Elife. 2021;10.

Chu H, Chan CM, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and bat coronavirus HKU9 both can utilize GRP78 for attachment onto host cells. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(30):11709–26.

Dai J, Wang P, Bai F, Town T, et al. Icam-1 participates in the entry of west Nile virus into the central nervous system. J Virol. 2008;82(8):4164–8.

D’Alessandro A, Thomas T, Dzieciatkowska M, Hill RC, et al. Serum proteomics in COVID-19 patients: altered coagulation and complement status as a function of IL-6 level. J Proteome Res. 2020;19(11):4417–27.

Deeb SJ, Tyanova S, Hummel M, Schmidt-Supprian M, et al. Machine learning-based classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients by their protein expression profiles. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14(11):2947–60.

Desrumaux C, Lemaire-Ewing S, Ogier N, Yessoufou A, et al. Plasma phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) modulates adaptive immune functions through alternation of T helper cell polarization. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(6):795–804.

Escher R, Breakey N, Lammle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res. 2020;190:62.

Eslava-Alcon S, Extremera-Garcia MJ, Gonzalez-Rovira A, Rosal-Vela A, et al. Molecular signatures of atherosclerotic plaques: an up-dated panel of protein related markers. J Proteomics. 2020;221:103757.

Gadanec LK, McSweeney KR, Qaradakhi T, Ali B, et al. Can SARS-CoV-2 virus use multiple receptors to enter host cells? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):992.

Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, Wang X, et al. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54(1):12–6.

Grabowski M, Murgueitio MS, Bermudez M, Wolber G, et al. The novel small-molecule antagonist MMG-11 preferentially inhibits TLR2/1 signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;171:113687.

Gu L, Casserly D, Brady G, Carpenter S, et al. Myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen controls the pathogen-stimulated type I interferon cascade in human monocytes by transcriptional regulation of IRF7. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):14.

Guervilly C, Burtey S, Sabatier F, Cauchois R, et al. Circulating endothelial cells as a marker of endothelial injury in severe COVID-19. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(11):1789–93.

Ha DP, Van Krieken R, Carlos AJ, Lee AS. The stress-inducible molecular chaperone GRP78 as potential therapeutic target for coronavirus infection. J Infect. 2020;81(3):452–82.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220–32.

Hur J, Yoon CH, Kim HS, Choi JH, et al. Characterization of two types of endothelial progenitor cells and their different contributions to neovasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):288–93.

Hwang IK, Park SM, Kim SY, Lee ST. A proteomic approach to identify substrates of matrix metalloproteinase-14 in human plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1702(1):79–87.

Jin Y, Ji W, Yang H, Chen S, et al. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in COVID-19: from basic mechanisms to potential therapeutic approaches. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):293.

Keihanian F, Bigdelu L. Cardiovascular considerations in COVID19: a comprehensive review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2020;16:1089–97.

Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7.

Krenning G, van Luyn MJ, Harmsen MC. Endothelial progenitor cell-based neovascularization: implications for therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(4):180–9.

Kronbichler A, Kresse D, Yoon S, Lee KH, et al. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:180–6.

Ladikou EE, Sivaloganathan H, Milne KM, Arter WE, et al. Von Willebrand factor (vWF): marker of endothelial damage and thrombotic risk in COVID-19? Clin Med (lond). 2020;20(5):e178–82.

Li WD, Li XQ. Endothelial progenitor cells accelerate the resolution of deep vein thrombosis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2016;83:10–6.

Liu X, Cao Y, Fu H, Wei J, et al. Proteomics analysis of serum from COVID-19 patients. ACS Omega. 2021;6(11):7951–8.

Mancuso P, Gidaro A, Gregato G, Raveane A, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitors are increased in COVID-19 patients and correlate with SARS-CoV-2 RNA in severe cases. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2744–50.

Marone EM, Rinaldi LF. Upsurge of deep venous thrombosis in patients affected by COVID-19: preliminary data and possible explanations. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(4):694–5.

McArdle A, Washington KE, Chazarin Orgel B, Binek A, et al. Discovery proteomics for COVID-19: where we are now. J Proteome Res. 2021;20(10):4627–39.

Medina RJ, O’Neill CL, O’Doherty TM, Knott H, et al. Myeloid angiogenic cells act as alternative M2 macrophages and modulate angiogenesis through interleukin-8. Mol Med. 2011;17(9–10):1045–55.

Medina RJ, Barber CL, Sabatier F, Dignat-George F, et al. Endothelial progenitors: a consensus statement on nomenclature. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(5):1316–20.

Mehta SR, Yusuf S. Short- and long-term oral antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(4 Suppl S):79S-88S.

Messner CB, Demichev V, Wendisch D, Michalick L, et al. Ultra-high-throughput clinical proteomics reveals classifiers of COVID-19 infection. Cell Syst. 2020;11(1):11–24.

Millet JK, Kien F, Cheung CY, Siu YL, et al. Ezrin interacts with the SARS coronavirus Spike protein and restrains infection at the entry stage. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e49566.

Nagashima S, Mendes MC, Camargo Martins AP, Borges NH, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis in patients with COVID-19-brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(10):2404–7.

Nizzoli ME, Merati G, Tenore A, Picone C, et al. Circulating endothelial cells in COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;95(8):E187–8.

Oliveira-Nascimento L, Massari P, Wetzler LM. The role of TLR2 in infection and immunity. Front Immunol. 2012;3:79.

Othumpangat S, Noti JD, McMillen CM, Beezhold DH. ICAM-1 regulates the survival of influenza virus in lung epithelial cells during the early stages of infection. Virology. 2016;487:85–94.

Palmeira A, Sousa E, Koseler A, Sabirli R, et al. Preliminary virtual screening studies to identify GRP78 inhibitors which may interfere with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pharmaceuticals (basel). 2020;13(6):132.

Palmisano G, Lendal SE, Engholm-Keller K, Leth-Larsen R, et al. Selective enrichment of sialic acid-containing glycopeptides using titanium dioxide chromatography with analysis by HILIC and mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(12):1974–82.

Patra R, Chandra Das N, Mukherjee S. Targeting human TLRs to combat COVID-19: a solution? J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):615–7.

Perez-Riverol Y, Csordas A, Bai J, Bernal-Llinares M, et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D442–50.

Potje SR, Costa TJ, Fraga-Silva TFC, Martins RB, et al. Heparin prevents in vitro glycocalyx shedding induced by plasma from COVID-19 patients. Life Sci. 2021;276:119376.

Poyatos P, Luque N, Sebastián L, Bonnin M, et al. Post-COVID-19 patients show an increased endothelial progenitor cell production. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(suppl 65):OA2593.

Queisser KA, Mellema RA, Middleton EA, Portier I, et al. COVID-19 generates hyaluronan fragments that directly induce endothelial barrier dysfunction. JCI Insight. 2021;6(17).

Ra SH, Lim JS, Kim GU, Kim MJ, et al. Upper respiratory viral load in asymptomatic individuals and mildly symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thorax. 2021;76(1):61–3.

Ries C, Egea V, Karow M, Kolb H, et al. MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and TIMP-2 are essential for the invasive capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells: differential regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Blood. 2007;109(9):4055–63.

Roy NH, Lambele M, Chan J, Symeonides M, et al. Ezrin is a component of the HIV-1 virological presynapse and contributes to the inhibition of cell-cell fusion. J Virol. 2014;88(13):7645–58.

Sariol A, Perlman S. SARS-CoV-2 takes its Toll. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(7):801–2.

Satoh K, Nagano T, Seki N, Tomita Y, et al. High level of serum cholesteryl ester transfer protein in active hepatitis C virus infection. World J Hepatol. 2016;8(5):291–300.

Shen B, Yi X, Sun Y, Bi X, et al. Proteomic and metabolomic characterization of COVID-19 patient sera. Cell. 2020;182(1):59–72.

Shi Z, Wen B, Gao Q, Zhang B. Feature selection methods for protein biomarker discovery from proteomics or multiomics data. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2021;20:100083.

Shin J, Toyoda S, Nishitani S, Fukuhara A, et al. Possible involvement of adipose tissue in patients with older age, obesity, and diabetes with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) via GRP78 (BIP/HSPA5): significance of hyperinsulinemia management in COVID-19. Diabetes. 2021;70(12):2745–55.

Shipton D, McCartney G, McMaster R. Population health post-pandemic: critiquing the economic approach to recovery. Public Health Pract (oxf). 2021;2:100098.

Shu T, Ning W, Wu D, Xu J, et al. Plasma proteomics identify biomarkers and pathogenesis of COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;53(5):1108–22.

Snell J. SARS-CoV-2 infection and its association with thrombosis and ischemic stroke: a review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;40:188–92.

Teuwen LA, Geldhof V, Pasut A, Carmeliet P. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(7):389–91.

Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–6.

Tong M, Jiang Y, Xia D, Xiong Y, et al. Elevated expression of serum endothelial cell adhesion molecules in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(6):894–8.

Tyanova S, Temu T, Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc. 2016a;11(12):2301–19.

Tyanova S, Temu T, Sinitcyn P, Carlson A, et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods. 2016b;13(9):731–40.

Vega FM, Gautier V, Fernandez-Ponce CM, Extremera MJ, et al. The atheroma plaque secretome stimulates the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells ex vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;105:12–23.

Wang K, Gheblawi M, Oudit GY. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2: a double-edged sword. Circulation. 2020;142(5):426–8.

Ward SE, Fogarty H, Karampini E, Lavin M, et al. ADAMTS13 regulation of VWF multimer distribution in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(8):1914–21.

Wicik Z, Eyileten C, Jakubik D, Simoes SN, et al. ACE2 interaction networks in COVID-19: a physiological framework for prediction of outcome in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):3743.

Wool GD, Miller JL. The impact of COVID-19 disease on platelets and coagulation. Pathobiology. 2021;88(1):15–27.

Wu Q, Zhou L, Sun X, Yan Z, et al. Altered lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients twelve years after infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9110.

Xia XD, Alabi A, Wang M, Gu HM, et al. Membrane-type I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), lipid metabolism, and therapeutic implications. J Mol Cell Biol. 2021;13(7):513–26.

Yamaoka-Tojo M. Vascular endothelial glycocalyx damage in COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9712.

You Y, Yang X, Hung D, Yang Q, et al. Asymptomatic COVID-19 infection: diagnosis, transmission, population characteristics. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2021.

Yu X, Shang H, Jiang Y. ICAM-1 in HIV infection and underlying mechanisms. Cytokine. 2020;125:154830.

Zamanian-Azodi M, Arjmand B, Razzaghi M, Rezaei Tavirani M, et al. Platelet and haemostasis are the main targets in severe cases of COVID-19 infection; a system biology study. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2021;9(1):e27.

Zhang M, Malik AB, Rehman J. Endothelial progenitor cells and vascular repair. Curr Opin Hematol. 2014;21(3):224–8.

Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(7):829–38.

Zhou Q, MacArthur MR, He X, Wei X, et al. Interferon-alpha2b treatment for COVID-19 is associated with improvements in lung abnormalities. Viruses. 2020;13(1):44.

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nurses, medical doctors and other workers of the National Paraplegic Hospital in Toledo that helped in the serum and data collection used in this study, especially to Carmen Rosell. Thanks to the Andalusian Bioinformatics Platform Center, Malaga University for the assistance with IPA software. We also thank the “Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental-CIBERSAM” (CB/07/09/0033). Some images were obtained via SMART (https://smart.servier.com).

Funding

This study was supported by GLOBALCAJA-Ayuda COVID-19 and Fondo Supera COVID-19, Banco Santander and CRUE universidades, Ref. IPSA-COVID-19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RML designed and managed the logistics of recruitment, collection, stratification and samples storage. MPMN, VMB and IGDLT, patient recruitment and determination of patient infection by rt-PCR. LBC, SEA and MRT performed ELISA assays to confirm the patients’ infective stage (IgG/IgM). SEA and LBC performed proteomic analysis of serum and CACs respectively. LBC performed functional/biological analyses, and designed the figures and tables. LBC and MCD evaluated the final data, wrote the main draft, edited and revised the manuscript. RML, JAM, EB and MCD conceptualized the project, and revised the manuscript, providing final suggestions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee, in accordance to Spanish and European Union Regulations and it follows the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All donors provided informed consent prior sample collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Serology test for antibodies detection results for PCR + samples. The table includes (from left to right): Number of serum sample, PCR test for virus detection results, ELISA test for IgM and IgG detection results. Table S2. Quantitative analysis of proteins differentially expressed in serum samples (vs Neg). The table includes (from left to right): Protein IDs (Uniprot accession number), protein description, PCR + /Neg ratio, PCR + /Neg p-value, IgG + /Neg ratio and IgG + /Neg p-value. Over-expressed values are indicated in red (considering up-regulated ratio > 1.5) and under-expressed values in green (down-regulated ratio < 0.6). The table shows the significant values for at least one of the comparisons (p-value < 0.05 as differentially significant). Table S3. Quantitative analysis of proteins differentially expressed in CACs incubated with serum samples of asymptomatic donors (vs Neg). The table includes (from left to right): Protein IDs (Uniprot accession number), protein description, PCR + /Neg ratio, PCR + /Neg p-value, IgG + /Neg ratio and IgG + /Neg p-value. Over-expressed values are indicated in red (considering up-regulated ratio > 1.5) and under-expressed values in green (down-regulated ratio < 0.6). The table shows the significant values for at least one of the comparisons (p-value < 0.05 as differentially significant). Table S4. Proteins highlighted by Naïve Bayes (NB) model for classifying CACs incubated with serum samples of asymptomatic donors (PCR + , IgG + and Negative). The analysis test mode used fivefold cross-validation. The table includes (from left to right): Protein IDs (Uniprot accession number), gen name and protein description. Table S5. Proteins highlighted by support vector machines (SVM) model for classifying CACs incubated with serum samples of asymptomatic donors (PCR + , IgG + and Negative). The analysis test mode used fivefold cross-validation. The table includes (from left to right): Protein IDs (Uniprot accession number), gen name and protein description. Table S6. Proteins highlighted by Random Forest model for classifying CACs incubated with serum samples of asymptomatic donors (PCR + , IgG + and Negative). The analysis test mode used fivefold cross-validation. The table includes (from left to right): Protein IDs (Uniprot accession number), gen name and protein description.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beltrán-Camacho, L., Eslava-Alcón, S., Rojas-Torres, M. et al. The serum of COVID-19 asymptomatic patients up-regulates proteins related to endothelial dysfunction and viral response in circulating angiogenic cells ex-vivo. Mol Med 28, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-022-00465-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-022-00465-w