Abstract

An incomplete postcranial skeleton of a snake from the middle Miocene of the Swiss Molasse in Käpfnach mine, near Zurich, Switzerland, is described in this paper. The skeleton is rather crushed and resting on a block of coal, with only some articulated vertebrae partially discerned via visual microscopy. We conducted micro-CT scanning in the specimen and we digitally reconstructed the whole preserved vertebral column, allowing a direct and detailed observation of its vertebral morphology. Due to the flattened nature of the fossil specimen, several individual vertebral structures are deformed, not permitting thus a secure precise taxonomic identification. Accordingly, we only refer the specimen to as Colubriformes indet. Nevertheless, this occurrence adds to the exceedingly rare fossil record of snakes from Switzerland, which had so far been formally described solely from three other Eocene and Miocene localities.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

During the past couple of decades, the application of micro-CT scanning has revolutionized squamate anatomical research, as, being non-invasive and non-destructive, it has allowed comprehensive study of internal structures and skeletal elements that would be otherwise fully inaccessible or at least would be viewed only in a single view. Such prominent cases that were quintessentially aided by micro-CT scanning include the documentation of fossil skeletons of lizards and snakes embedded on matrix (e.g., Čerňanský et al., 2017; Klembara & Čerňanský, 2020; Smith & Habersetzer, 2021; Smith & Scanferla, 2021), squamates included in fossil amber (Bolet et al., 2021; Čerňanský et al., 2022; Daza et al., 2018), the investigation of the microanatomy, histology, and other internal structures in isolated fossil remains (e.g., Georgalis & Scheyer, 2019, 2021; Georgalis et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2018), as well as the study of the skeletal anatomy of extant squamates that are either rare in museum wet collections or either too delicate to be properly skeletonized (e.g., Bell et al., 2021; Čerňanský & Syromyatnikova, 2021; Gauthier et al., 2012; Klembara et al., 2017; Linares-Vargas et al., 2021; Martins et al., 2021). Accordingly, this recent wave of CT-scanning-based squamate research has allowed novel anatomical interpretations, thus leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the evolution, anatomy, and phylogenetic affinities of extant and extinct lizards and snakes.

We here describe a partial, postcranial fossil skeleton of a snake from the middle Miocene of the Swiss Molasse in Käpfnach mine, near Zurich, Switzerland. The skeleton, embedded on a block of coal and still partially covered by a thin coal layer, is rather crushed and only some articulated vertebrae can be directly visible. With the application of micro-CT scanning in the specimen and subsequent 3D imaging, we digitally reconstruct the preserved vertebral column and elucidate many aspects of its vertebral morphology, which would have otherwise remained obscure, providing clues about its taxonomic determination.

2 Institutional abbreviations

HNHM, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary; MDHC, Massimo Delfino Herpetological Collection, University of Torino, Torino, Italy; MNCN, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain; MNHN, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France; NHMUK, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; NHMW, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria; PIMUZ, Palaeontological Institute and Museum of the University of Zurich, Switzerland; ZZSiD, Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, Poland.

3 Locality

The specimen PIMUZ A/III 191 originates from the Käpfnach coal mine, near Horgen, in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. The locality pertains to the Upper Freshwater Molasse (OSM), which spans from the late early to the early late Miocene (MN 4b–MN 9). In particular, more precisely, the Käpfnach coal mine is considered to be of a middle Miocene (Langhian, MN 5) age (Krsnik et al., 2021). The molasse lignite/coal deposits of Horgen/Käpfnach on the left bank of the Zurich lake were already mentioned in the chronicle of Johannes Stumpf in 1548 (Stumpf, 1548) and mining activities occurred, with several interruptions, until 1946 (Pavoni, 1957). Vertebrate fossils became known from the locality since more than two centuries, which is famous especially for its abundant fossil remains of large mammals, such as proboscideans and rhinocerotids, but generally pertaining to a number of different tetrapod groups (e.g., Kaup, 1859; Mennecart et al., 2021; Pickford, 2016; Schinz, 1822, 1833).

4 Material and methods

The partial snake skeleton described herein is permanently curated at the collections of PIMUZ. The specimen was recovered from the Käpfnach mine in 1938 and has remained undescribed since then. This is partially because the bone and coal did not separate well so that initial mechanical preparation of some of the vertebrae was causing too much surface damage to the bones; the remainder of the specimen was thus left unprepared. It was micro-CT scanned using a Nikon XTH 225 ST CT Scanner housed at the Anthropological Department of the University of Zurich. The micro-computed tomography scan of the specimen PIMUZ A/III 191 was taken using a 1 mm copper filter, and with a voltage of 181 kV and a current of 206 μA, yielding a voxel size of 0.056026 mm. The datasets were then visualized using Materialise Mimics Version 23. The micro-CT scan data and the 3D surface files (.PLY files) are available on Morphosource repository (https://www.morphosource.org/) (see “Availability of data and materials” below for details); the 3D surface files, along with a flythrough video of the micro-CT scan are also available in Additional files 1, 2, 3 and 4. Comparative vertebral material of extant and extinct snakes was studied at the collections of HNHM, MDHC, MNCN, MNHN, NHMUK, NHMW, PIMUZ, and ZZSiD.

5 Systematic palaeontology

Squamata Oppel, 1811

Serpentes Linnaeus, 1758

Alethinophidia Nopcsa, 1923

Caenophidia Hoffstetter, 1939

Colubroides Zaher et al., 2009

Colubriformes Günther, 1864 (sensu Zaher et al., 2009).

Colubriformes indet.

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4, Additional files 1, 2, 3 and 4.

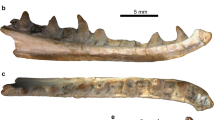

Colubriformes indet. (PIMUZ A/III 191) from the middle Miocene of Käpfnach, Switzerland. a 3D model of the skeleton indicating the position of the two segmented vertebrae; b–g 3D models of the first vertebra in anterior (b), posterior (c), right lateral (d), left lateral (e), dorsal (f), and ventral (g) views; h–m 3D models of the second vertebra in anterior (h), posterior (i), right lateral (j), left lateral (k), dorsal (l), and ventral (m) views

Colubriformes indet. (PIMUZ A/III 191) from the middle Miocene of Käpfnach, Switzerland. Axial section of the micro-CT scan, indicating the presence of paracotylar foramen (note that this is only one section, more or less horizontal, through the vertebra, and as such, does not show the location of the foramen as would be visible from outside, but only a single position of the foramen as it enters and progresses into and extends within the centrum)

Material: PIMUZ A/III 191, a partial articulated postcranial skeleton (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4, Additional files 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Description: PIMUZ A/III 191 is a partial, incomplete skeleton, comprising 21 preserved articulated trunk vertebrae and many ribs (Figs. 1, 2 and 3; Additional file 1). Judging from the width of the haemal keel and the depth of the subcentral grooves, these vertebrae originate from the mid- to posterior trunk portion of the column. The specimen is highly crushed, being dorsoventrally compressed, so that many structures in the vertebrae cannot be fully discerned or are deformed, particularly when seen in anterior, posterior, and lateral views. The vertebrae are relatively small and much longer than wide (centrum length of approximately 6.7 mm and neural arch width of approximately 5.5 mm; average ratio of centrum length to neural arch width of approximately 1.22). The following description is based on the two segmented vertebrae, which represent the 10th and 11th vertebrae among the preserved articulated series (Fig. 3b–m; Additional files 2 and 3), but some structures are discerned from other vertebrae where these are more fully preserved. In anterior view (Fig. 3b, h), most structures appear rather deformed. The neural spine is moderately thick. The zygosphene is thin. The neural canal is practically not visible as, due to the crush, the zygosphene has reached the dorsal level of the cotyle. The prezygapophyses are dorsally inclined, though their degree of that inclination cannot be properly assessed. The synapophyses extend ventrally from the ventral level of the cotyle. Paracotylar foramina are present, as it can be observed in the axial view of the micro-CT scan (Fig. 4; Additional file 4). In posterior view (Fig. 3c, i), the zygantrum is highly crushed. The condyle is dorsoventrally flattened, though this flattening could arise of course due to the overall crushed nature of the vertebra. In lateral view (Figs. 2c and 3d, e, j, k), the neural spine is not fully preserved in any vertebra but seems to have been moderately high; it abruptly augments in height anteriorly and seems to possess approximately that same height throughout its length (Fig. 2c). The interzygapophyseal ridges are rather blunt. Lateral foramina are present, situated into a deep depression below the interzygapophyseal ridge. In dorsal view (Figs. 2b and 3f, l), the neural spine crosses most of the midline of the neural arch; it commences behind the posterior border of the zygosphene. The shape of the zygosphene cannot be properly assessed but it seems that it possessed distinct lateral lobes. Prezygapophyses extend more laterally than anteriorly. Prezygapophyseal articular facets are large and oval-shaped. Prezygapophyseal accessory processes are present and relatively prominent and elongated. The interzygapophyseal constriction is moderately deep. Epizygapophyseal spines are present in the postzygapophyses. The posterior median notch of the neural arch is very deep. In ventral view (Figs. 2b and 3g, m), the haemal keel is moderately wide; it is considerably thicker towards its posterior edge and a constriction is present around its half-length. The haemal keel crosses almost the whole midline of the centrum, commencing anteriorly from the ventral lip of the cotyle and terminating posteriorly slightly prior to the posteroventral edge of the condyle. The subcentral grooves are prominent and rather deep. Subcentral foramina are present. The subcentral ridges are blunt and roughly straight. The synapophyses are well-divided into diapophyses and parapophyses.

6 Discussion

A precise taxonomic identification of the partial skeleton PIMUZ A/III 191 is hampered by its incomplete and crushed nature, as well as the current poor understanding of the systematics and vertebral morphology of Neogene snakes. PIMUZ A/III 191 can be referred to Colubriformes based on the combination of the following features: vertebrae lightly built and longer than wide, the presence of paracotylar foramina and elongated prezygapophyseal accessory processes, and synapophyses divided into diapophyses and parapophyses (Rage, 1984; Zaher et al., 2019). It should be noted also that an elongation of the centrum is also present outside colubriforms, e.g., in vertebrae of scolecophidians and ungaliophiids (Georgalis & Smith, 2020; Smith, 2013; Smith & Georgalis, 2022; Szyndlar, 1991), however, their morphology is distinctly different than the Swiss Miocene snake.

Colubriformes represents the dominant and most diverse snake group globally since the onset of the Miocene and is particularly rich and abundant in the Neogene and Quaternary of Europe (Szyndlar, 1991, 2012; Zaher et al., 2009, 2019). Within Colubriformes, the absence of hypapophyses in mid- and posterior trunk vertebrae in PIMUZ A/III 191 excludes its referral to natricids, elapids, and viperids, which all had a widespread fossil record in the European Miocene. In palaeontological literature, all colubriforms from Eurasia which lacked hypapophyses in their mid- and posterior trunk vertebrae have been traditionally lumped together into a paraphyletic assemblage termed “Colubrinae” (e.g., Georgalis et al., 2018; Rage, 1984; Szyndlar, 1984, 1991, 2012); a similar trend also applied for long time among herpetologists, who were lumping most extant colubriforms without hypapophyses in mid- and posterior trunk vertebrae into an expanded concept of Colubridae (e.g., Bogert, 1940; Boulenger, 1896; Bourgeois, 1968; Dowling & Duellman, 1978; Underwood, 1967). However, recent phylogenies have disentangled the affinities among many colubriform lineages, revealing that certain of these “colubrines” or colubrids are not actually related to “true” Colubridae (Georgalis et al., 2018, 2019; Szyndlar, 2012). Such notable European (extinct and extant) examples represent the dipsadids and psammophiids, which have a “typical” colubrid vertebral morphology, lacking hypapophyses in mid- and posterior trunk vertebrae, but are only much distantly related to Colubridae (Georgalis & Szyndlar, 2022; Georgalis et al., 2019). Among these two non-colubrid groups, dipsadids are absent in extant European herpetofaunas but are present in the continent during the Miocene (Rage & Holman, 1984; Villa et al., 2021), while psammophiids first appear in Europe in the latest Miocene and are still components of its ophidian fauna (Georgalis & Szyndlar, 2022; Szyndlar, 1991, 2012; Villa et al., 2021). In addition, during the Miocene, Europe was also inhabited by certain colubriform taxa that also lacked hypapophyses in mid- and posterior trunk vertebrae, but cannot be safely assigned to a particular group, for example Texasophis Holman, 1977 (e.g., Rage & Holman, 1984; Szyndlar, 1987, 1991).

Certain interesting features of the Swiss fossil, which can still be assessed despite its crushed preservational state, include the neural spine crossing most of the neural arch and abruptly augmenting in height in its anterior border (rather than a gradual augmentation), the moderately wide haemal keel with a constriction at around its mid-height, the deep posterior median notch of the neural arch, the elongation of the prezygapophyseal accessory processes, the moderately deep interzygapophyseal constriction, and the presence of paracotylar foramina. These features nevertheless, are all widespread among Neogene and Quaternary European colubriforms (excluding natricids, elapids, and viperids). Furthermore, as already aptly emphasized by Szyndlar (1991, 2012), a genus-level vertebral identification of the Neogene and Quaternary small-sized colubriforms from Europe is a considerably difficult task, due to the general resemblance among vertebrae of most different species as well as the high degree of intraspecific and intracolumnar variation.

As such, we cannot refer with certainty PIMUZ A/III 191 to either Colubridae, Dipsadidae, Psammophiidae, or even some other (unknown) colubriform lineage; in any case though, we would expect psammophiid affinities as less likely due to a stratigraphic rationale (the Swiss specimen is much older than the first appearance of this group in Europe). Accordingly, we only tentatively identify the Swiss specimen as Colubriformes indet. Nevertheless, this new indeterminate colubriform from the middle Miocene of Käpfnach adds to the so far poorly documented and exceedingly rare fossil record of snakes from Switzerland, which was up to now confined exclusively to constrictors from the middle–late Eocene of Dielsdorf, Canton Zurich (Georgalis & Scheyer, 2019; Rosselet, 1991) and the late Eocene of the Mount Mormont, Canton Vaud (Pictet et al., 1855–1857), as well as a few fragmentary remains of indeterminate viperids and ?colubrids from the early Miocene of Wallenried, Canton Fribourg (Mennecart et al., 2016). Micro-CT scanning and 3D imaging technologies currently offer an unprecedented potential to further explore such “elusive” fossil specimens embedded on matrices, allowing more comprehensive studies on the evolution and taxonomic composition of squamates from Europe.

Availability of data and materials

The fossil specimen PIMUZ A/III 191 described and figured herein is permanently curated at the collections of PIMUZ. The CT scans and 3D models of the specimen are deposited at the Morphosource repository (https://www.morphosource.org/): CT image series of PIMUZ A/III 191 (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M430440); 3D model of PIMUZ A/III 191 (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M430443); 3D model of the first segmented vertebra of PIMUZ A/III 191 (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M430446); 3D model of the second segmented vertebra of PIMUZ A/III 191 (https://doi.org/10.17602/M2/M430449). The 3D models of the whole specimen and the two segmented vertebrae of PIMUZ A/III 191, along with a flythrough video of the micro-CT scan are also available in the Additional Information of this article (Additional files 1, 2, 3 and 4).

References

Bell, C. J., Daza, J. D., Stanley, E. L., & Laver, R. J. (2021). Unveiling the elusive: X-rays bring scolecophidian snakes out of the dark. The Anatomical Record, 304, 2110–2117.

Bogert, C. M. (1940). Herpetological results of the Vernay Angola expedition, with notes on African reptiles in other collections. Part I. Snakes, including an arrangement of African Colubridae. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 77, 1–107.

Bolet, A., Stanley, E. L., Daza, J. D., Arias, J. S., Čerňanský, A., Vidal-García, M., Bauer, A. M., Bevitt, J. J., Peretti, A., & Evans, S. E. (2021). Unusual morphology in the mid-Cretaceous lizard Oculudentavis. Current Biology, 31, 3303–3314.

Boulenger, G. Α. (1896). Catalogue of the snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume 3, containing the Colubridæ (Opisthoglyphæ and Proteroglyphæ), Amblycephalidæ, and Viperidæ (p. 727). London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History).

Bourgeois, M. (1968). Contribution à la morphologie comparée du crane des ophidiens de l’Afrique Centrale. Publications de'l universitè Officielle du Congo à Lubumbashi, 18, 1–293.

Čerňanský, A., Bolet, A., Müller, J., Rage, J.-C., Augé, M., & Herrel, A. (2017). A new exceptionally preserved specimen of Dracaenosaurus (Squamata, Lacertidae) from the Oligocene of France as revealed by micro-computed tomography. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 37, e1384738.

Čerňanský, A., Stanley, E. L., Daza, J. D., Bolet, A., Arias, J. S., Bauer, A. M., Vidal-García, M., Bevitt, J. J., Peretti, A. M., Aung, N. N., & Evans, S. E. (2022). A new Early Cretaceous lizard in Myanmar amber with exceptionally preserved integument. Scientific Reports, 12, 1660.

Čerňanský, A., & Syromyatnikova, E. V. (2021). The first pre-Quaternary fossil record of the clade Mabuyidae with a comment on the enclosure of the Meckelian canal in skinks. Papers in Palaeontology, 7, 195–215.

Daza, J. D., Bauer, A. M., Stanley, E. L., Bolet, A., Dickson, B., & Losos, J. B. (2018). An enigmatic miniaturized and attenuate whole lizard from the mid-Cretaceous amber of Myanmar. Breviora, 563, 1–18.

Dowling, H. G., & Duellman, W. E. (1978). Systematic herpetology: A synopsis of families and higher categories (p. 240). Herpetological Information Search Service.

Gauthier, J. A., Kearney, M., & Maisano, J. A. (2012). Assembling the squamate tree of life: Perspectives from the phenotype and the fossil record. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 53, 3–208.

Georgalis, G. L., Čerňanský, A., & Klembara, J. (2021). Osteological atlas of new lizards from the Phosphorites du Quercy (France), based on historical, forgotten, fossil material. Geodiversitas, 43(9), 219–293.

Georgalis, G. L., Rage, J.-C., de Bonis, L., & Koufos, G. (2018). Lizards and snakes from the late Miocene hominoid locality of Ravin de la Pluie (Axios Valley, Greece). Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 111, 169–181.

Georgalis, G. L., & Scheyer, T. M. (2019). A new species of Palaeopython (Serpentes) and other extinct squamates from the Eocene of Dielsdorf (Zurich, Switzerland). Swiss Journal of Geosciences, 112, 383–417.

Georgalis, G. L., & Scheyer, T. M. (2021). Lizards and snakes from the earliest Miocene of Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France: An anatomical and histological approach of some of the oldest Neogene squamates from Europe. BMC Ecology and Evolution, 21, 144.

Georgalis, G. L., & Smith, K. T. (2020). Constrictores Oppel, 1811—The available name for the taxonomic group uniting boas and pythons. Vertebrate Zoology, 70, 291–304.

Georgalis, G. L., & Szyndlar, Z. (2022). First occurrence of Psammophis (Serpentes) from Europe witnesses another Messinian herpetofaunal dispersal from Africa—Biogeographic implications and a discussion of the vertebral morphology of psammophiid snakes. The Anatomical Record. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24892

Georgalis, G. L., Villa, A., Ivanov, M., Vasilyan, D., & Delfino, M. (2019). Fossil amphibians and reptiles from the Neogene locality of Maramena (Greece), the most diverse European herpetofauna at the Miocene/Pliocene transition boundary. Palaeontologia Electronica, 22.3.68, 1–99.

Günther, A. C. L. G. (1864). The reptiles of British India (p. 452). London: Ray Society.

Hoffstetter, R. (1939). Contribution à l’étude des Elapidæ actuels et fossiles et de l’ostéologie des Ophidiens. Archives du Muséum d’histoire Naturelle de Lyon, 15, 1–78.

Holman, J. A. (1977). Amphibians and reptiles from the Gulf Coast Miocene of Texas. Herpetologica, 33, 391–403.

Kaup, J. J. (1859). Beiträge zur näheren Kenntniss der urweltlichen Säugethiere (Vol. 4, p. 31). Darmstadt: J. G. Heyer.

Klembara, J., & Čerňanský, A. (2020). Revision of the cranial anatomy of Ophisaurus acuminatus Jörg, 1965 (Anguimorpha, Anguidae) from the late Miocene of Germany. Geodiversitas, 42(28), 539–557.

Klembara, J., Dobiašová, K., Hain, M., & Yaryhin, O. (2017). Skull anatomy and ontogeny of legless lizard Pseudopus apodus (Pallas, 1775): Heterochronic influences on form. The Anatomical Record, 300, 460–502.

Krsnik, E., Methner, K., Campani, M., Botsyun, S., Mutz, S. G., Ehlers, T. A., Kempf, O., Fiebig, J., Schlunegger, F., & Mulch, A. (2021). Miocene high elevation in the Central Alps. Solid Earth, 12, 2615–2631.

Linares-Vargas, C. A., Bolívar-García, W., Herrera-Martínez, A., Osorio-Domínguez, D., Ospina, O. E., Thomas, R., & Daza, J. D. (2021). The status of the anomalepidid snake Liotyphlops albirostris and the revalidation of three taxa based on morphology and ecological niche models. The Anatomical Record, 304, 2264–2278.

Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (p. 824). Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii.

Martins, A., Koch, C., Joshi, M., Pinto, R., Machado, A., Lopes, R., & Passos, P. (2021). Evolutionary treasures hidden in the West Indies: Comparative osteology and visceral morphology reveals intricate miniaturization in the insular genera Mitophis Hedges, Adalsteinsson, & Branch, 2009 and Tetracheilostoma Jan, 1861 (Leptotyphlopidae: Epictinae: Tetracheilostomina). The Anatomical Record, 304, 2118–2148.

Mennecart, B., Métais, G., Costeur, L., Ginsburg, L., & Rössner, G. E. (2021). Reassessment of the enigmatic ruminant Miocene genus Amphimoschus Bourgeois, (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Pecora). PLoS ONE, 16, e0244661.

Mennecart, B., Yerly, B., Mojon, P.-O., Angelone, C., Maridet, O., Böhme, M., & Pirkenseer, C. (2016). A new Late Agenian (MN2a, Early Miocene) fossil assemblage from Wallenried (Molasse Basin, Canton Fribourg, Switzerland). Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 90, 101–123.

Nopcsa, F. (1923). Eidolosaurus und Pachyophis. Zwei Neue Neocom-Reptilien. Palaeontographica, 65, 99–154.

Oppel, M. (1811). Die Ordnungen, Familien und Gattungen der Reptilien als Prodrom einer Naturgeschichte derselben (p. 87). Munich: Joseph Lindauer.

Pavoni, N. (1957). Geologie der Zürcher Molasse zwischen Albiskamm und Pfannenstiel. Vierteljahrsschrift der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich, 102, 117–315.

Pickford, M. (2016). Biochronology of European Miocene Tetraconodontinae (Suidae, Artiodactyla, Mammalia) flowing from recent revision of the Subfamily. Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien, 118A, 175–244.

Pictet, F. J., Gaudin, C. T., & de La Harpe, P. (1855–1857). Mémoire sur les Animaux vertébrés trouvés dans le terrain Sidérolithique du Canton de Vaud et appartenant à la faune Eocène. Matériaux pour la Paléontologie Suisse, 1, 1–120.

Rage, J.-C. (1984). Serpentes. In S. Wellnhofer (Ed.), Encyclopedia of paleoherpetology, part 11 (p. 80). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer.

Rage, J.-C., & Holman, J. A. (1984). Des serpents (Reptilia, Squamata) de type nord-américain dans le Miocène français. Evolution parallèle ou dispersion? Geobios, 17, 89–104.

Rosselet, C. (1991). Die fauna der Spaltenfüllungen von Dielsdorf (Eozän, Kanton Zürich). Documenta Naturae, 64, 1–177.

Schinz, H. R. (1822). Entdeckung fossiler Zähne and Knochen, zu Käpfnach am Züricher-See. Naturwissenschaftlicher Anzeiger der Allgemeinen Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für die Gesammten Naturwissenschaften, 5, 72.

Schinz, H. R. (1833). Ueber die Ueberreste organischer Wesen, welche in den Kohlengruben des Cantons Zürich bisher aufgefunden wurden. Denkschriften der allgemeinen Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für die gesammten Naturwissenschaften. Ersten Bandes zweyte Abtheilung, 39–64.

Smith, K. T. (2013). New constraints on the evolution of the snake clades Ungaliophiinae, Loxocemidae and Colubridae (Serpentes), with comments on the fossil history of erycine boids in North America. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 252, 157–182.

Smith, K. T., Bhullar, B.-A.S., Köhler, G., & Habersetzer, J. (2018). The only known jawed vertebrate with four eyes and the bauplan of the pineal complex. Current Biology, 28, 1101–1107.

Smith, K. T., & Georgalis, G. L. (2022). The diversity and distribution of Palaeogene snakes: A review, with comments on vertebral sufficiency. In D. Gower & H. Zaher (Eds.), The origin and early evolution of snakes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, K. T., & Habersetzer, J. (2021). The anatomy, phylogenetic relationships, and autecology of the carnivorous lizard “Saniwa” feisti Stritzke, 1983 from the Eocene of Messel, Germany. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 20(23), 441–506.

Smith, K. T., & Scanferla, A. (2021). A nearly complete skeleton of the oldest definitive erycine boid (Messel, Germany). Geodiversitas, 43, 1–24.

Stumpf, J. (1548). Gemeiner loblicher Eydgnoschafft Stetten, Landen und Völckeren Chronick wirdiger Thaaten Beschreybung. Christoffel Froschouer, Getruckt Zürych in der Eydgnoschafft, 467 pp.

Szyndlar, Z. (1984). Fossil snakes from Poland. Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia, 28, 1–156.

Szyndlar, Z. (1987). Snakes from the lower Miocene locality of Dolnice (Czechoslovakia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 7, 55–71.

Szyndlar, Z. (1991). A review of Neogene and Quaternary snakes of Central and Eastern Europe. Part I: Scolecophidia, Boidae Colubrinae. Estudios Geológicos, 47, 103–126.

Szyndlar, Z. (2012). Early Oligocene to Pliocene Colubridae of Europe: A review. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, 183, 661–681.

Underwood, G. (1967). A contribution to the classification of snakes. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), 653, 1–179.

Villa, A., Carnevale, G., Pavia, M., Rook, L., Sami, M., Szyndlar, Z., & Delfino, M. (2021). An overview of the late Miocene vertebrates from the fissure fillings of Monticino Quarry (Brisighella, Italy), with new data on non-mammalian taxa. Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 127, 297–354.

Zaher, H., Grazziotin, F. G., Cadle, J. E., Murphy, R. W., Cesar de Moura-Leite, J., & Bonatto, S. L. (2009). Molecular phylogeny of advanced snakes (Serpentes, Caenophidia) with an emphasis on South American xenodontines: A revised classification and descriptions of new taxa. Papéis Avulsos De Zoologia, 49, 115–153.

Zaher, H., Murphy, R. W., Arredondo, J. C., Graboski, R., Machado-Filho, P. R., Mahlow, K., Montingelli, G. G., Bottallo Quadros, A., Orlov, N. L., Wilkinson, M., Zhang, Y.-P., & Grazziotin, F. G. (2019). Large-scale molecular phylogeny, morphology, divergence-time estimation, and the fossil record of advanced caenophidian snakes (Squamata: Serpentes). PLoS ONE, 14(5), e0216148.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra (PIMUZ) for an initial invitation to study the material, the curator Christian Klug (PIMUZ) for access to the collection under his care, and Jorge Carrillo‑Briceño (PIMUZ) for help with micro-CT scanning. For access to comparative extant and fossil skeletal material, we thank Zbigniew Szyndlar (ZZSiD), Massimo Delfino (MDHC), Silke Schweiger and Georg Gassner (NHMW), Marta Calvo Revuelta (MNCN), Judit Vörös (HNHM), and Mike Day and Sandra Chapman (NHMUK). The quality of the paper was improved by useful comments provided by the Editor Daniel Marty and three anonymous reviewers.

Funding

GLG acknowledges funding from the Ulam Program of the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (PPN/ULM/2020/1/00022/U/00001) and Forschungskredit of the University of Zurich, Grant no. [FK-20-110]. Funding support for visiting collections came from SYNTHESYS ES-TAF-5910 (MNCN), SYNTHESYS AT-TAF-5911 (NHMW), SYNTHESYS HU-TAF-6145 (HNHM), and SYNTHESYS GB-TAF-6591 (NHMUK) to GLG. TMS acknowledges support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant no. 31003A_179401).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GLG and TMS wrote the manuscript; GLG photographed the specimen; TMS and GLG processed the micro-CT scans and the 3D images; GLG and TMS prepared the figures. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Editorial handling: Daniel Marty.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Model 1.

3D model of the partial skeleton PIMUZ A/III 191 of Colubriformes indet. from the middle Miocene of Käpfnach, Switzerland.

Additional file 2: Model 2.

3D model of the first segmented vertebra of PIMUZ A/III 191.

Additional file 3: Model 3.

3D model of the second segmented vertebra of PIMUZ A/III 191.

Additional file 4. Flythrough video of the micro-CT scan of the partial skeleton PIMUZ A/III 191 of Colubriformes indet. from the middle Miocene of Käpfnach, Switzerland.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Georgalis, G.L., Scheyer, T.M. Crushed but not lost: a colubriform snake (Serpentes) from the Miocene Swiss Molasse, identified through the use of micro-CT scanning technology. Swiss J Geosci 115, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-022-00417-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-022-00417-w