Abstract

Background

Our objective was to evaluate the impact of gastric versus post-pyloric feeding on the incidence of pneumonia, caloric intake, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS), and mortality in critically ill and injured ICU patients.

Method

Data sources were Medline, Embase, Healthstar, citation review of relevant primary and review articles, personal files, and contact with expert informants. From 122 articles screened, nine were identified as prospective randomized controlled trials (including a total of 522 patients) that compared gastric with post-pyloric feeding, and were included for data extraction. Descriptive and outcomes data were extracted from the papers by the two reviewers independently. Main outcome measures were the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia, average caloric goal achieved, average daily caloric intake, time to the initiation of tube feeds, time to goal, ICU LOS, and mortality. The meta-analysis was performed using the random effects model.

Results

Only medical, neurosurgical and trauma patents were enrolled in the studies analyzed. There were no significant differences in the incidence of pneumonia, percentage of caloric goal achieved, mean total caloric intake, ICU LOS, or mortality between gastric and post-pyloric feeding groups. The time to initiation of enteral nutrition was significantly less in those patients randomized to gastric feeding. However, time to reach caloric goal did not differ between groups.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis we were unable to demonstrate a clinical benefit from post-pyloric versus gastric tube feeding in a mixed group of critically ill patients, including medical, neurosurgical, and trauma ICU patients. The incidences of pneumonia, ICU LOS, and mortality were similar between groups. Because of the delay in achieving post-pyloric intubation, gastric feeding was initiated significantly sooner than was post-pyloric feeding. The present study, while providing the best current evidence regarding routes of enteral nutrition, is limited by the small total sample size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enteral nutrition is increasingly being recognized as an integral component in the management of critically ill patients, having a major effect on morbidity and outcome. Early enteral nutrition has been demonstrated to improve nitrogen balance, wound healing and host immune function, and to augment cellular antioxidant systems, decrease the hypermetabolic response to tissue injury and preserve intestinal mucosal integrity [1–7]. In a previous study [8], we reported that initiation of enteral nutrition within 36 hours of surgery or admission to hospital reduces infectious complications and hospital length of stay (LOS).

These data suggest that enteral nutrition should be initiated as soon as possible after admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). Although the gastric route of enteral feeding is easier to achieve and cheaper than post-pyloric nutrient administration, many clinicians worry that gastric feeding predisposes to aspiration and pneumonia. Thus, many prefer to feed critically ill patients via the post-pyloric route, believing that it reduces the incidence of pneumonia. Although the study by Heyland and colleagues [9] suggests that gastrically fed patients may have a higher incidence of aspiration than those receiving post-pyloric feeding, other investigators have not replicated these findings [10]. In addition, many critically ill, injured, and postoperative patients have gastroparesis, which may limit their ability to tolerate gastric feeding [11, 12]. Indeed, Mentec and colleagues [13] demonstrated that 79% of gastrically fed patients in a mixed medical/surgical ICU exhibited some degree of upper digestive intolerance caused by impaired gastric emptying. Despite poor gastric emptying, small bowel function usually remains relatively intact and placement of a post-pyloric small bowel feeding tube may allow for the administration of enteral nutrition in these patients. However, placement of small bowel feeding tubes may be extremely challenging and result in a delay in the initiation of enteral feeding. Although a number of randomized controlled trials comparing gastric with post-pyloric feeding in critically ill patients have been performed, the results of these studies have been inconclusive and/or conflicting. Thus, the 'best' route of enteral nutrition in the critically ill and injured remains unclear.

In order to further our understanding of the clinical effects of gastric versus small intestinal nutrient administration in critically ill patients, we performed a meta-analysis of available studies to compare the pulmonary complications, clinical outcomes, and success in achieving caloric goals in patients randomly assigned to receive either gastric or small intestinal tube feeds.

Method

Identification of trials

Our aim was to identify all relevant randomized controlled trials that compared gastric with small intestinal tube feeds in critically ill patients. A randomized controlled trial was defined as a trial in which patients were assigned prospectively to one of two interventions by random allocation. We used a multimethod approach to identify relevant studies for the present review. A computerized literature search of the National Library of Medicine's Medline database from 1966 to July 2002 was conducted using the following search terms: enteral nutrition (explode) AND jejunal or post-pyloric or gastric AND randomized controlled trials (publication type) or controlled clinical trials or clinical trials, randomized. In addition, we searched the Embase (1980–2001) and Health-star (1975–2001) databases, reviewed our personal files, and contacted experts in the field. Bibliographies of all selected articles and review articles that included information on enteral nutrition were reviewed for other relevant articles. This search strategy was done iteratively, until no new potential, randomized, controlled trial citations were found on review of the reference lists of retrieved articles.

Study selection and data extraction

The following selection criteria were used to identify published studies for inclusion in this analysis: study design-randomized clinical trial; population – hospitalized adult postoperative, trauma, head injured, burn, or medical ICU patients; intervention – gastric versus small intestinal enteral nutrition, initiated at the same time and with the same caloric goal; and outcome variables – at least one of the following primary outcome variables: incidence of nosocomial pneumonia, average caloric goal achieved, average daily caloric intake, time to the initiation of tube feeds, time to reach caloric goal, ICU LOS, and mortality. Study selection and data abstraction was conducted independently by the two investigators.

Data analysis

The incidence of nosocomial pneumonia and mortality were treated as binary variables. Percentage of caloric goal achieved, mean daily caloric intake, time to the initiation of tube feeds, time to goal, and ICU LOS were treated as continuous variables. Data analysis was performed using the random effects model with meta-analysis software (RevMan 4.1; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The odds ratio (OR) and continuous data outcomes are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When authors reported standard deviations, we used them directly. When standard deviations were not available, we computed them from the observed mean differences (either differences in changes or absolute readings) and the test statistics. When the test statistics were not available, given a P value, we computed the corresponding test statistic from tables for the normal distribution. We tested heterogeneity between trials with χ2 tests, with P < 0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity [14].

Results

From 122 articles screened, 14 were identified as randomized controlled trials comparing gastric versus small intestinal enteral nutrition and were included for data extraction. These 14 publications were identified through Medline searches; no unpublished studies, personal communications, or data reported in abstract form only were included. Five studies were excluded, and the remaining nine trials were included in the present meta-analysis [10, 15–22]. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: the end-points of interest were not recorded [9, 23], non-ICU patients were studied [24], and two studies compared early (post-pyloric or gastric) versus delayed (gastric) enteral nutrition [25, 26], Only medical, neurosurgical, and trauma patents were enrolled in the studies analyzed. Overall, 552 patients were enrolled in the included studies. A summary of the studies, including the incidences of pneumonia and caloric goal achieved, are presented in Table 1. Not all of the studies reported the end-points of interest, with risk for pneumonia being reported in seven studies [15–17, 19–22], mean percentage of caloric goal achieved in five studies [10, 15, 17–19], mean caloric intake in five studies [15, 17, 19–21], time to the initiation of enteral nutrition in three studies [15, 20, 21], time to reach caloric goal in four studies [16, 18, 20, 22], ICU LOS in five studies [15–17, 20, 21], and mortality in seven studies [10, 15–18, 20, 21].

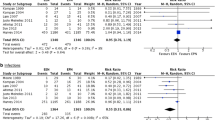

There were no significant differences in the incidence of pneumonia (OR 1.44, 95% CI 0.84–2.46, P = 0.19; Fig. 1), percentage of caloric goal achieved (-5.2%, 95% CI -18.0% to +7.5%, P = 0.4; Fig. 2), mean total caloric intake (-169 calories, 95% CI -320 to +34 calories, P = 0.09), ICU LOS (-1.4 days, 95% CI -3.7 to +0.85 days, P = 0.2), or mortality (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.69–1.68, P = 0.7) between those patients fed gastrically and those who received postpyloric tube feeding. Although the time to the initiation of enteral nutrition was reported in only three studies, it was significantly shorter in those patients randomly assigned to receive nutrition by the gastric route (-16.0 hours, 95% CI -19.5 to -12.6 hours, P < 0.00001). However, the time to reach caloric goal did not differ between the two groups (-0.78 hours, gastric versus jejunal, 95% CI -3.76 to +2.19 hours, P = 0.6).

Discussion

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that the incidence of pneumonia, caloric goal achieved, ICU LOS, and mortality are similar with gastric and post-pyloric tube feeding. Although enteral nutrition was initiated sooner in the gastrically fed patients, patients fed into the small intestine 'caught up' with the patients fed into the stomach and overall received a non-significantly greater mean daily caloric intake (169 calories). We previously reported that enteral nutrition initiated within 36 hours of surgery or admission to the ICU reduces the incidence of infectious complications as compared with nutrition delayed for greater than 36 hours [8]. The time to the initiation of enteral nutrition was significantly shorter in those patients randomly assigned to receive nutrition by the gastric route (-16.0 hours, 95% CI -19.5 to -12.6 hours, P < 0.00001). Although it is possible that the short delay in the initiation of enteral nutrition in the small intestine fed patients could increase infective complications, the results of this analysis do not support that contention.

This study has a number of limitations that must be recognized. A total of only 552 patients were included in the meta-analysis, the outcomes variables of interest were not recorded in all studies, and there was significant heterogeneity between studies for a number of the outcome variables. Furthermore, none of the studies included patients who had undergone abdominal or major vascular surgery. These latter patients are at high risk for gastroparesis and are best managed by a small bowel feeding tube placed intraoperatively [8, 27, 28].

The relative risk for pneumonia in the gastric compared with the post-pyloric fed group in this analysis was 1.44 (95% CI 0.84–2.46, P = 0.19). Although this may suggest a trend toward an increased risk for pneumonia in the gastric group, this is questionable for a number of reasons. First, there was significant heterogeneity in the studies, making extrapolation of conclusions fraught with error. Second, ICU LOS was actually decreased in the gastric group (-1.4 days, CI -3.7 to +0.85, P = 0.2). If the risk for pneumonia was significantly increased in these critically ill patients, one might anticipate an increase rather than a decrease in ICU LOS. In addition, pneumonia was not associated with any increase in mortality (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.69–1.68, P = 0.7). However, the study was not powered to detect a smaller but still clinically significant difference in the incidence of pneumonia between the two groups of patients.

Placement of small bowel feeding tubes by the blind nasoenteric approach is technically challenging. Zaloga [29] described the 'corkscrew' method of achieving post-pyloric placement of feeding tubes, with a success rate of 92%. Although success rates as high as 90% have been claimed by others for placing post-pyloric feeding tubes at the bedside [30–32], most studies report a success rate of 15–30% [33–36]. Success with bedside placement of small bowel feeding tubes is influenced by the technique and degree of expertise of the clinician. Furthermore, unlike a nasogastric/orogastric tube, which can be passed in less than a minute, it can take an experienced operator up to 30 minutes to achieve post-pyloric placement of a small bowel feeding tube. In order to improve the success at post-pyloric placement, modifications have been made to the feeding tubes, including lengthening the tube, altering the configuration and profile of the tip, and adding various types of weights [34, 37, 38]. Innovative methods of placement have been described that include using industrial magnets, bedside sonography, fiberoptics through the tube, gastric insufflation, and electrocardiogram-guided placement [33, 37–40]. Prokinetic agents have also been used to improve the likelihood of trans-pyloric passage of the feeding tube [35, 39–42]. The number of variations and modifications of the blind bedside technique attest to the fact that none is ideal. Furthermore, misplacement of the small bore feeding tube into the lung with resultant pneumothorax is not a rare complication [43–47].

In order to improve the success rate of the blind bedside technique, small bore feeding tubes may be placed endoscopically or radiographically. Hillard and coworkers [36] compared the success rate and time to placement of small bowel feeding tubes placed by fluoroscopy as compared with placement at the bedside. Of fluoroscopic procedures 91% were successful, as compared with a success rate of 17% with bedside placement. The average time delay before initiation of feeding was 28.1 hours for the bedside method and 7.5 hours for fluoroscopy. Although both fluoroscopy and endoscopy are highly effective for placement of small bowel feeding tubes, they require expertise that is not readily available 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. These techniques frequently require patient transfer to specialized areas of the hospital where the procedures are performed. In addition, both techniques are expensive.

An alternative to the use of a small intestinal feeding tube is to place a regular orogastric or nasogastric tube into the stomach and to use a promotility agent in those patients who are at high risk for gastroparesis or in those who develop high gastric residuals (>150–250 ml). Although Mentec and colleagues [13] demonstrated some degree of upper digestive intolerance in 79% of nasogastrically fed patients, only 4.5% were unable to tolerate continuation of gastric feeding. In the study conducted by Boivin and Levy [18], all gastrically fed patients received erythromycin as a promotility agent. In the studies conducted by Kortbeek and coworkers and by Esparza and colleagues, promotility agents were only used in patients with increased gastric residual volumes [9, 10, 16]. For economic reasons, as well as to avoid potential side effects, it could be argued that only those patients who are intolerant of nasogastric feedings (residual >150–250 ml) should receive a prokinetic agent. Erythromycin has been demonstrated to improve nutrient delivery, but the impact of this agent on antibiotic resistance, diarrhea, and other complications has been poorly evaluated.

Although the present report indicates no difference between gastric and small intestinal feedings with regard to the incidence of pneumonia, LOS, or mortality, the trials that comprise the meta-analysis did not study patients at high risk for aspiration. Such patients would include those with previous aspiration, anatomic abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract, and those with high gastric residuals (i.e. >250 ml) or those maintained in the recumbent position. Small bowel feeding may be the preferred route of enteral feeding in these high-risk patients.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis we failed to find any clinical benefits of small intestinal feeding over gastric feeding for the nutritional support of a mixed group of critically ill medical, neurosurgical, and trauma patients. Both routes of enteral nutrition were associated with similar rates of pneumonia, LOS, and mortality. The studies evaluated in this meta-analysis demonstrated heterogeneity, and the sample size was inadequate to detect small differences between the groups; the results should therefore be interpreted with some caution. However, based upon the results of this analysis and our experience feeding critically ill patients, we recommend that critically ill patients who are not at high risk for aspiration have a nasogastric/orogastric tube placed on admission to the ICU for the early initiation of enteral nutrition. Promotility agents should be considered in patients with high gastric residual volumes. Patients who remain intolerant of gastric tube feeding despite the use of promotility agents or patients with clinically significant reflux or documented aspiration should have a small intestinal feeding tube inserted for continuation of enteral nutritional support. Patients undergoing major intra-abdominal surgery who are at high risk for gastroparesis should preferably be fed with a small bowel feeding tube placed intraoperatively.

Key messages

-

Post-pyloric feeding has no clinical advantages over gastric feeding in most critically ill medical, neurosurgical and trauma patients

-

Early gastric feeding with an oro-gastric or naso-gastric tube is favored in most critically ill patients

-

Promotility agents are recommended in patients with high gastric residuals

-

Post-pyloric feeding is recommended in patients at high risk of aspiration, in patients undergoing major intra-abdominal surgery and patients who are intolerant of gastric feeding

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

= confidence interval

- ICU:

-

= intensive care unit

- LOS:

-

= length of stay

- OR:

-

= odds ratio.

References

Hadfield RJ, Sinclair DG, Houldsworth PE, Evans TW: Effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on gut mucosal permeability in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152: 1545-1548.

Gianotti L, Alexander JW, Nelson JL, Fukushima R, Pyles T, Chalk CL: Role of early enteral feeding and acute starvation on post-burn bacterial translocation and host defense: prospective, randomized trials. Crit Care Med 1994, 22: 265-272.

Minard G, Kudsk KA: Is early feeding beneficial? How early is early? New Horiz 1994, 2: 156-163.

Chuntrasakul C, Siltharm S, Chinswangwatanakul V, Pongprasobchai T, Chockvivatanavanit S, Bunnak A: Early nutritional support in severe traumatic patients. J Med Assoc Thailand 1996, 79: 21-26.

Tanigawa K, Kim YM, Lancaster JR Jr, Zar HA: Fasting augments lipid peroxidation during reperfusion after ischemia in the perfused rat liver. Crit Care Med 1999, 27: 401-406. 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00049

Bortenschlager L, Roberts PR, Black KW, Zaloga GP: Enteral feeding minimizes liver injury during hemorrhagic shock. Shock 1994, 2: 351-354.

Beier-Holgersen R, Brandstrup B: Influence of early postoperative enteral nutrition versus placebo on cell-mediated immunity, as measured with the Multitest CMI. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999, 34: 98-102. 10.1080/00365529950172907

Marik PE, Zaloga GP: Early enteral nutrition in acutely ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 2264-2270.

Heyland DK, Drover JW, MacDonald S, Novak F, Lam M: Effect of postpyloric feeding on gastroesophageal regurgitation and pulmonary microaspiration: results of a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1495-1501. 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00001

Esparza J, Boivin MA, Hartshorne MF, Levy H: Equal aspiration rates in gastrically and transpylorically fed critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2001, 27: 660-664. 10.1007/s001340100880

Jooste CA, Mustoe J, Collee G: Metoclopramide improves gastric motility in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 1999, 25: 464-468. 10.1007/s001340050881

Heyland DK, Tougas G, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH: Cisapride improves gastric emptying in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients. A randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 154: 1678-1683.

Mentec H, Dupont H, Bocchetti M, Cani P, Ponche F, Bleichner G: Upper digestive intolerance during enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: frequency, risk factors, and complications. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1955-1961. 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00018

Oxman AD, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH: Users guide to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence-based working group. JAMA 1994, 272: 1367-1371. 10.1001/jama.272.17.1367

Montecalvo MA, Steger KA, Farber HW, Smith BF, Dennis RC, Fitzpatrick GF, Pollack SD, Korsberg TZ, Birkett DH, Hirsch EF: Nutritional outcome and pneumonia in critical care patients randomized to gastric versus jejunal tube feedings. The Critical Care Research Team. Crit Care Med 1992, 20: 1377-1387.

Kortbeek JB, Haigh PI, Doig C: Duodenal versus gastric feeding in ventilated blunt trauma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma 1999, 46: 992-998.

Kearns PJ, Chin D, Mueller L, Wallace K, Jensen WA, Kirsch CM: The incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia and success in nutrient delivery with gastric versus small intestinal feeding: a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 1742-1746. 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00007

Boivin MA, Levy H: Gastric feeding with erythromycin is equivalent to transpyloric feeding in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2001, 29: 1916-1919. 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00011

Day L, Stotts NA, Frankfurt A, Stralovich-Romani A, Volz M, Muwaswes M, Fukuoka Y, O'Leary-Kelley C: Gastric versus duodenal feeding in patients with neurological disease: a pilot study. J Neurosci Nurs 2001, 33: 148-149.

Davies AR, Froomes PRA, French CJ, Bellomo R, Gutteridge GA, Nyulasi I, Walker R, Sewell RB: Randomized comparison of nasojejunal and nasogastric feeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 586-590. 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00016

Montejo JC, Grau T, Acosta J, Ruiz-Santana S, Planas M, Garcia-de-Lorenzo A, Mesejo A, Cervera M, Sanchez-Alvarez C: Multi-center, prospective, randomized, single-blindstudy comparing the efficacy and gastrointestinal complications of early jejunal feeding with early gastric feeding in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 796-800. 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00013

Neumann DA, DeLegge MH: Gastric versus small-bowel tube feeding in the intensive care unit: a prospective comparison of efficacy. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 1436-1438. 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00006

Heiselman DE, Hofer T, Vidovich RR: Enteral feeding tube placement success with intravenous metoclopramide administration in ICU patients. Chest 107: 1686-1688.

Strong RM, Condon SC, Solinger MR, Namihas BN, Ito-Wong LA, Leuty JE: Equal aspiration rates from postpylorus and intra-gastric-placed small-bore nasoenteric feeding tubes: a randomized, prospective study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1992, 16: 59-63.

Minard G, Kidsk KA, Melton S, Patton JH, Tolley EA: Early versus delayed feeding with an immune-enhancing diet in patients with severe head injuries. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2000, 24: 145-149.

Taylor SJ, Fettes SB, Jewkes C, Nelson RJ: Prospective, randomized, controlled trial to determine the effect of early enhanced enteral nutrition on clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients suffering head injury. Crit Care Med 1999, 27: 2525-2531. 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00033

Silk DB, Gow NM: Postoperative starvation after gastrointestinal surgery. Early feeding is beneficial. BMJ 2001, 323: 761-762. 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.761

Lewis SJ, Egger M, Sylvester PA, Thomas S: Early enteral feeding versus 'nil by mouth' after gastrointestinal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMJ 2001, 323: 773-776. 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.773

Zaloga GP: Bedside method for placing small bowel feeding tubes in critically ill patients. A prospective study. Chest 1991, 100: 1643-1646.

Smith HG, Orlando R III: Enteral nutrition: should we feed the stomach? Crit Care Med 1999, 27: 1652-1653. 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00050

Davis TJ, Sun D, Dalton ML: A modified technique for bedside placement of nasoduodenal feeding tubes. J Am Coll Surg 1994, 178: 407-409.

Thurlow PM: Bedside enteral feeding tube placement into duodenum and jejunum. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1986, 10: 104-105.

Marian M, Rappaport W, Cunningham D, Thompson C, Esser M, Williams F, Warneke J, Hunter G: The failure of conventional methods to promote spontaneous transpyloric feeding tube passage and the safety of intragastric feeding in the critically ill ventilated patient. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993, 176: 475-479.

Rees RG, Payne-James JJ, KIng C, Silk DB: Spontaneous transpyloric passage and performance of 'fine bore' polyurethrane feeding tubes: a controlled clinical trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1988, 12: 469-472.

Hernandez-Socorro CR, Marin J, Ruiz-Santana S, Santana L, Manzano JL: Bedside sonographic-guided versus blind nasoenteric feeding tube placement in critically ill patients. rit Care Med 1996, 24: 1690-1694. 10.1097/00003246-199610000-00015

Hillard AE, Waddell JJ, Metzler MH, McAlpin D: Fluoroscopically guided nasoenteric feeding tube placement versus bedside placement. South Med J 1995, 88: 425-428.

Lord LM, Weiser-Maimone A, Pulhamus M, Sax HC: Comparison of weighted vs unweighted enteral feeding tubes for efficacy of transpyloric intubation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1993, 7: 271-273.

Paz HL, Weinar M, Sherman MS: Motility agents for the placement of weighted and unweighted feeding tubes in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 1996, 22: 301-304. 10.1007/s001340050084

Gabriel SA, Ackermann RJ, Castresana MR: A new technique for placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes using external magnetic guidance. Crit Care Med 1997, 25: 641-645. 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00014

Grathwohl KW, Gibbons RV, Dillard TA, Horwhat JD, Roth BJ, Thompson JW, Cambier PA: Bedside videoscopic placement of feeding tubes: development of fiberoptics through the tube. rit Care Med 1997, 25: 629-634. 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00012

Spalding HK, Sullivan KJ, Soremi O, Gonzalez F, Goodwin SR: edside placement of transpyloric feeding tubes in the pediatric intensive care unit using gastric insufflation. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 2041-2044. 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00060

Keidan I, Gallagher TJ: Electrocardiogram-guided placement of enteral feeding tubes. Crit Care Med 2000, 28: 2631-2633.

Kaufman JP, Hughes WB, Kerstein MD: Pneumothorax after nasoenteral feeding tube placement. Am Surg 2001, 67: 772-773.

Wendell GD, Lenchner GS, Promisloff RA: Pneumothorax complicating small-bore feeding tube placement. Arch Intern Med 1991, 151: 599-602. 10.1001/archinte.151.3.599

Arsura EL, Munoz AD: Pneumothorax following feeding tube placement. Arch Intern Med 1991, 151: 2473-2476. 10.1001/archinte.151.12.2473a

Kools AM, Snyder LS, Cass OW: Pneumothorax: complication of enteral feeding tube placement. Dig Dis Sci 1987, 32: 1212-1213.

Khan MS, Gross JS: Pneumothorax complicating small-bore nasogastric feeding tube insertion. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987, 35: 1130-1131.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Marik, P.E., Zaloga, G.P. Gastric versus post-pyloric feeding: a systematic review. Crit Care 7, R46 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2190

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc2190