Abstract

Introduction

The diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis is made from a combination of clinical features and the presence of radiographic evidence that may be detected only after many years of inflammatory back pain. It is not uncommon to have a diagnosis confirmed 5 to 10 years after the initial onset of symptoms. Development of a more-sensitive molecular imaging technology to detect structural changes in the joints would lead to earlier diagnosis and quantitative tracking of ankylosis progression. Progressive ankylosis (ank/ank) mice have a loss of function in the Ank gene, which codes for a regulator of PPi transport. In this study, we used these ank/ank mutant mice to assess a noninvasive, quantitative measure of joint ankylosis with near-infrared (NIR) molecular imaging in vivo.

Methods

Three age groups (8, 12, and 18 weeks) of ank/ank (15 mice) and wild-type littermates (12 +/+ mice) were assessed histologically and radiographically. Before imaging, OsteoSense 750 (bisphosphonate pamidronate) was injected i.v. Whole-body images were analyzed by using the multispectral Maestro imaging system.

Results

OsteoSense 750 signals in the paw joints were higher in ank/ank mice in all three age groups compared with controls. In the spine, significantly higher OsteoSense 750 signals were detected early, in 8-week-old ank/ank mice compared with controls, although minimal radiographic differences were noted at this time point. The molecular imaging changes in the ank/ank spine (8 weeks) were supported by histologic changes, including calcium apatite crystals at the edge of the vertebral bodies and new syndesmophyte formation.

Conclusions

Changes in joint pathology of ank/ank mice, as evaluated by histologic and radiographic means, are qualitative, but only semiquantitative. In contrast, molecular imaging provides a quantitative assessment. Ankylosis in ank/ank mice developed simultaneously in distal and axial joints, contrary to the previous notion that it is a centripetal process. NIR imaging might be feasible for early disease diagnosis and for monitoring disease progression in ankylosing spondylitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Outbred homozygous ank (progressive ankylosis) mice represent a highly informative model for studying the biologic basis of joint ankylosis. In these mice, a single gene mutation alters an inorganic pyrophosphate transporter and is associated with spontaneous joint ankylosis [1]. In a pattern similar to that of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in humans, the ankylosis in these mice affects peripheral and spinal joints [1]. The central features of AS are spinal inflammation and ankylosis [2]. As spinal structural changes as visualized on radiographs appear relatively late in most AS patients, it is not uncommon for a delay of 5 to 10 years after the initial onset of symptoms before the diagnosis is made. Our colony of ank/ank mice exhibits ankylosis without joint inflammation [3]. This unique feature offers an opportunity to analyze ankylosis directly in the mutant mice in the absence of confounding joint inflammation.

Near-infrared (NIR) probes, which generate high signal-to-noise ratios, have the potential for noninvasive quantitative fluorescence imaging in whole animals [4]. OsteoSense 750 (VisEN Medical, Bedford, MA, USA) is an NIR fluorescent bisphosphonate (pamidronate) that targets hydroxyapatite for monitoring skeletal changes [5]. With this NIR probe, bone growth and remodeling can be imaged with high sensitivity and resolution, and mineralization can be quantified.

Previous radiographic studies documented that aberrant mineralization in ank/ank joints occurred in a centripetal fashion (that is, from distal to proximal joints [6]), but the mechanisms underlying the temporal and progressive manner of ankylosis remain unclear. In this study, we attempted to define the dynamics of ankylosis progression in ank/ank mice by using the more-sensitive and quantitative molecular imaging method, and we obtained a surprising result.

Materials and methods

ankmice and injection of OsteoSense 750 probe

The ank/ank mice (outbred) were generated by crossbreeding heterozygous mice. Wild-type (+/+) littermates were used as controls. For this study, 15 mutant (ank/ank) and 12 wild-type mice were evaluated. Three age groups of mice were analyzed (8, 12, and 18 weeks). Twenty-four hours before imaging, OsteoSense 750 (VisEN) was injected into the tail veins at the recommended dose of 2 nmol/150 ml per mouse. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Experimentation Committee.

In vivomolecular imaging and analysis

Whole-body and lower-body images of injected mice were acquired by using the Maestro in vivo imaging system (CRI Inc., Santa Maria, CA, USA; excitation: 671 to 705 nm; emission: 750 to 950 nm). The Maestro optical system uses a liquid crystal tunable filter (30-nm bandwidth; scanning wavelength range, 500 to 950 nm), a 16-bit high-resolution scientific-grade monochrome imaging sensor and Maestro 1.4.2 software for image acquisition and analysis. The imaging regions with pure autofluorescence spectra were manually selected and subtracted from the mixed fluorescence signal of the image to obtain the OsteoSense 750 fluorescence intensity at each imaging pixel recorded. Mean fluorescence intensities from the selected regions were normalized, measured, and finally, analyzed.

Radiographic and histologic analyses

After NIR imaging, radiographs of the killed mice were generated via a Faxitron unit (Hewlett Packard Faxitron X-ray system 43855 B; San Diego, CA, USA) by using similar settings for each mouse. For detection of structural differences, high-resolution electronic images of the radiographs were taken under similar conditions and exposures for each pair of mice (wild-type versus ank/ank) for each age group. For histologic analyses, the fixed joints were decalcified in 10% EDTA. After dehydration through a graded alcohol series, the tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned (at 5 mm), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney U tests (SPSS v18.0) were used to compare results from the wild-type versus mutant mice of different age groups. The P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Radiographic changes in ank/ankmice were observed earlier and more prominently in paw joints than in the axial skeleton

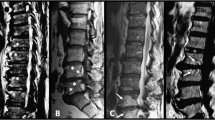

Our radiographic results of the ank/ank mice were comparable to those from previous reports [6]. We focused mainly on structural changes, in both the peripheral joints and the spine. The 8-week-old ank/ank mice showed increased mineralization in the distal interphalangeal joints (Figure 1B; white arrows). From 12 to 18 weeks, joint calcification became more pronounced progressively and extended to more proximal joints (Figure 1D and 1E; white arrows). The differences in the axial skeleton were subtle at 8 weeks, with early syndesmophytes at the vertebral corners of ank/ank mice (Figure 2B; red arrows). By 12 weeks, the corner syndesmophytes were well formed in the ank/ank vertebra (Figure 2D; red arrows), which progressed to syndesmophytes by 18 weeks (Figure 2E; red arrows).

Radiographs of spines from wild-type versus ank/ank mice. Eight-week-old mice appear in (A) and (B); 12-week-old mice in (C) and (D); and 18-week-old mice in (E) and (F). Red arrows in (B) show spurs between the vertebral bodies of 8-week-old ank/ank mice. Red arrows in (D) show early syndesmophytes at the edges of the vertebra from 12-week-old ank/ank mice. Red arrows in (F) show extensive marginal syndesmophyte formation between vertebral bodies from 18-week-old ank/ank mice.

Radiographic examination of the sacroiliac joints (SIJs) of ank/ank mice (8 and 12 weeks) revealed no ankylosis (Additional File 1). The resolution of the radiographs was insufficient for semiquantitative analysis of the radiographs.

In vivo molecular imaging showed higher axial OsteoSense 750 signals in 8-week-old ank/ankmice

Figure 3 shows the representative biodistribution of OsteoSense 750 signals of wild-type versus ank/ank mice (12 weeks; Figure 3A and 3B). Areas (in red) were marked for calculation of fluorescence signals (circled). As expected, paw joints of ank/ank mice from all three groups showed significantly higher fluorescence signals (expressed in mean photon counts with 95% confidence intervals) than did those of normal (+/+) littermates. The paw signals in ank/ank mice were 148 (112.1 to 184.8), 169.5 (111.3 to 227.8), and 87 (64.9 to 109) at 8, 12, and 18 weeks, respectively, compared with 84.4 (67.5 to 101.2), 64.9 (46.1 to 83.6), and 58.9 (31.6 to 86.2) at the corresponding age groups of wild-type littermates (Figure 4A). Interestingly, as early as 8 weeks of age, mean fluorescence signals from the lower spines of ank/ank mice were significantly higher than those from the wild-type (+/+) littermates of the same age group. At 8, 12, and 18 weeks, the spinal signals were 319.3 (274.9 to 363.7), 253.7 (177.1 to 330.3), and 271.1 (169.0 to 373.1), respectively, in ank/ank versus 200.2 (141.9 to 258.4), 134.7 (93.2 to 176.1), and 130.4 (111.7 to 149.1), respectively, in wild-type mice (Figure 4B). Comparisons of paw and spinal signals between wild-type and ank/ank mice in all three age groups showed significant differences (P < 0.05 at each age group; Figure 4A and 4B and Table 1).

In vivo imaging of wild-type versus ank/ank mice after injection of OsteoSense 750 probes. (A, B) Scans of 12-week-old wild-type versus ank/ank mice to identify fluorescent signals. For quantification of signals, selected areas for distal paws and spine are circled in yellow and white, respectively (C, D).

Spinal in vivomolecular imaging results were paralleled by histologic findings

The histomorphology of the vertebral column was significantly altered in 8-week-old ank/ank mice. Calcium apatite crystals were observed at the edges of the vertebral bodies (Figure 5B, thick arrow). Hypertrophic chondrocyte-like cells were replacing the annulus fibrosus (AF) and extending into the intervertebral disc (IVD; Figure 5B, thin arrow). Spinal sections of 12-week-old ank/ank mice showed a large amount of crystal deposition (Figure 5C, thin arrow) and early syndesmophyte formation (Figure 5C, thick arrow). The vertebral column of an 18-week-old ank/ank mouse showed ankylosis with fibrous connective tissue adjacent to some incomplete bony bridging (Figure 5D, thick arrow). The intervertebral disc at this stage was essentially replaced by a cellular proliferation composed of fibroblasts and large chondrocytic cells (Figure 5D, thin arrow). Higher magnification of the spinal sections showed that in wild-type mice, a few osteoblasts line the subchondral bone (Figure 6A, solid arrows). In 8-week ank/ank spine, the osteoblasts are more prominent and organized (Figure 6B, solid arrows), and calcific deposits (Figure 6B, dashed arrow) are present. In 12-week ank/ank spine, new bone formation (syndesmophyte, SYN; Figure 6C) developed where calcific deposits were located in younger mice. Numerous osteoblasts (solid arrows, Figure 6C) lined the new bone that was formed. Osteocytes are found embedded in the syndesmophyte (short dashed arrows; Figure 6C). In some ank/ank (18 weeks) spinal sections, large fusion masses of fibrocartilaginous tissues extend from one vertebra to the next, at the edges of the annulus fibrosus of the IVD (Figure 7). Within the fusion masses, "bone islands" appear, complete with bone marrow. These regions demonstrate the classic appearance of the growth plate, such as tidemark areas and organized subchondral layers (Figure 7, arrow).

Histologic examination of representative spine joints from wild-type versus ank/ank mice. (A) Vertebra from an 8-week-old wild type mouse. V, EC, AF, and IVD denote vertebra, endplate cartilage, annulus fibrosus, and intervertebral disc, respectively. (B) Vertebra from an 8-week-old ank/ank mouse. Thick arrow shows calcium apatite crystals at the edge of the vertebral bodies. Thin arrow shows hypertrophic chondrocyte-like cells replacing the annulus fibrosus and extending into the intervertebral disc. (C) Vertebra from a 12-wk-old ank/ank mouse. Thin arrow shows a large amount of crystal deposits. Thick arrow shows early syndesmophyte formation at the edge of the vertebral bodies. (D) Vertebra from an 18-week-old ank/ank mouse. Thick arrow shows ankylosis with fibrous connective tissue adjacent to some incomplete bony bridging. Thin arrow shows the intervertebral disc at this stage, and it was replaced by proliferative fibroblasts and large chondrocytic cells.

Higher magnification of spinal sections from 8-week-old wild-type (A) versus 8-week- (B), and 12-week-old (C) ank/ank mice. Arrows in (A) show a few osteoblasts lining the subchondral bone (SB). GP, VEP, and AF denote growth plate, vertebral end plate, and annulus fibrosus, respectively. Solid arrows in (B) show more-prominent osteoblasts in the vertebral body of an 8-week-old ank/ank spine. Dashed arrows show calcific deposits. Solid arrows in (C) show numerous osteoblasts lining the new bone that was formed in a 12-week-old ank/ank mouse. Embedded in the syndesmophyte (SYN) are osteocytes (short dashed arrows).

Comparison of spinal sections from wild-type (A) versus ank/ank mice across the intervertebral disc (IVD). (B) A spinal section from an 18-week-old ank/ank mouse. Large fusion masses of fibrocartilaginous tissues extend from one vertebra to the next, at the edges of the annulus fibrosus of the IVD. (C) A larger view of the marked rectangular area from (B). Within the fusion masses, "bone islands" are complete with bone marrow (BM). These regions demonstrate the classic appearance of the growth plate, such as tidemark areas (dotted black arrow) and organized subchondral layers (black arrow). The connective tissue/fibrous tissue masses seen in the ank/ank spine are largely ill defined (yellow arrow).

Discussion

In this study, our imaging results revealed a new insight into the axial ankylosis process in the ank/ank mice. Previous studies reported that aberrant mineralization in ank/ank joints occurred in a centripetal fashion (that is, from distal to proximal joints) [6]. In contrast, by using in vivo molecular imaging, we showed that ankylosis in ank/ank mice developed simultaneously in distal and axial joints, resulting in complete ankylosis at all skeletal sites by 18 weeks. Our novel molecular imaging finding was corroborated by spinal histologic assessments showing that synoviocytes/fibroblast proliferation and crystal deposits were observed in both interphalangeal (data not shown) and spinal joints as early as 8 weeks in ank/ank mice. In addition, our histologic analyses revealed a predominance of large chondrocytic cells at the sites of eventual ankylosis, suggesting that dysregulation of chondrocyte maturation underlies the development of ankylosis in ank/ank mice. Although we did not detect overt histologic abnormalities of osteoblasts, we cannot rule out the possibility that ank/ank osteoblasts have more activity contributing to excess mineralization in the mutant mice. It has been shown that the Ank protein plays an important role in osteoblastic differentiation [7]. However, osteoblasts (involved in endochondral ossification) might not be the major contributor to syndesmophyte formation. These syndesmophytes appear to be atypical as (a) they usually develop in the same sites where calcific deposition and prominent hypertrophic chondrocytes were located in the spine (enthesis) of younger mutant mice, indicating that they are likely more fibrocartilaginous in nature; (b) the connective tissue/fibrous tissue masses seen in the ank/ank spine (Figure 7) are largely ill defined; and (c) no discernible contiguous bone within the syndesmophyte connects one vertebra with the next. These features are in contrast to the typical osteophytes, which contain contiguous bony fusion masses emanating from the vertebral body, complete with bone marrow. To illustrate this latter feature (a typical osteophyte), we include a supplementary figure (Additional File 2) showing the spine from a chondrodystrophic canine (beagle) with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). The osteophytes affecting the lumbar spine clearly showed contiguous bony fusion (Additional File 2, panel a), and no ill-defined connective tissue/fibrous tissue mass appears (Additional File 2, panel b), which is a prominent feature in ank/ank spine.

Published reports have shown that bisphosphonates localize to osteoblastic and osteoclastic surfaces, depending on their side chains and dosages used. It has been documented [8, 9] that OsteoSense probe (NIR pamidronate) binds to (a) active osteoblastic surfaces, as shown by co-localization with alkaline phosphatase staining; and (b) osteoclastic surfaces by histology (localized in large osteoclast-like cells in resorption lacunae). However, these results were from very young mice (8-day-old neonates and 7- to 9-week-old mice). With the same NIR (OsteoSense 750) probe, our results showed that in normal mice, paw signals were significantly lower in older mice (for example, P = 0.029, comparing 8-week and 12-week wild-type mice). It is possible that fewer active surfaces were available in the paws of older mice (12 weeks or older), although no significantly different spine signals were seen between young and older normal mice. As with normal mice, no significant differences were found in spine signals from all three age groups of ank/ank mice; but these signals were all higher than those from the normal mice. In contrast, 18-week-old ank/ank mice had lower paw signals than did the younger mutant mice (8 versus 18 weeks; P = 0.01; 12 versus 18 weeks; P = 0.03). It is possible that in the paws, fewer active surfaces were present in the mutant mice by 18 weeks. Osteoblast/mineralization signals represent real-time snapshots of new bone formation. Other factors that might influence Osteosense signals include access of the probe from the vasculature to the mineralized surfaces. In another study [10], although hydroxyapatite (HA) deposits in arteries were detected, "skip" areas within the same vessel were also present. The reason for this phenomenon/heterogeneity remains unclear.

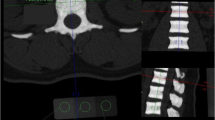

In ankylosing spondylitis, ankylosis is initiated at the sacroiliac joints. However, we did not find any ankylosis in the sacroiliac joints of the ank/ank mice (Additional File 1). Radiographs of low resolution might not be the best tool for assessment of ankylosis at the sacroiliac joints of mice. Micro-CT image assessments are required to address this issue. Alternatively, histologic evaluation of sacroiliac joints (not decalcified) after injection of a fluorescent bisphosphonate probe might be able to resolve this issue [11]. Although numerous phenotypic similarities exist between the ank/ank mice and AS, it is not unexpected that differences exist as well. Ankylosis in the ank/ank mouse is the consequence of a single gene defect. However, AS is a complex disease with multiple risk factors.

In the current study, we used one NIR (OsteoSense 750) probe at one particular fluorescence excitation (750). The capacity exists to use more than one NIR probe simultaneously for molecular imaging. For example, in addition to OsteoSense 750 probe, another NIR probe at fluorescence excitation of 680 (such as MMP) can be injected into the mice for simultaneous imaging of MMP localization and bone remodeling. Other molecular targets could also be imaged by using Alexa Fluor 680 fluorescent dye-conjugated specific antibodies. This has been successfully used for molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for monitoring cancer treatment by using the Maestro HIS system [12].

We need more-sensitive, objective, and quantitative assessments of joint ankylosis in AS patients. According to the modified New York criteria, the diagnosis of AS requires evidence of radiographic sacroiliitis. Sacroiliac joint radiographs are scored from grade 0 (normal) to grade 4 (ankylosis) [13]. Currently, the cervical and lumbar spines are scored according to the modified Stoke AS Spine Score (mSASSS) [14]. The interpretation of the sacroiliac radiographic assessments is notoriously very difficult. Our observation that higher OsteoSense 750 signals can be detected in 8-week-old ank/ank spine in which prominent radiographic abnormalities can yet be detected, suggests that this molecular imaging technology is an alternative to mSASSS for earlier AS diagnosis and the monitoring of disease progression in AS patients.

Among the NIR probes, only indocyanine green (ICG; absorption at 780 nm and emission at 820 nm) is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for clinical use [15]. A recent study demonstrated that ICG-enhanced optical imaging can detect joint inflammation in an antigen-induced arthritic mouse model [16]. Unfortunately, conjugation of ICG to proteins is difficult, as ICG is amphophilic and has few functional groups. In addition, ICG loses its fluorescence when bound to protein. To alleviate this problem, the use of quenching NIR probes (ICG-conjugated monoclonal antibodies) has been proposed [15]. Much further work in this respect is needed. Regarding detection systems, it would be ideal to have a hand-held device [17] to image sacroiliac joints and spine in the rheumatology clinic. The in vivo molecular imaging could shorten the time required to diagnose AS. In addition, this technology provides unbiased and high-quality assessments to monitor disease progression as well as the outcome of therapeutic treatments [18, 19].

Conclusions

We showed that molecular imaging is more sensitive than radiographs for the detection of early mineralization changes in the spines of ank/ank mice. The molecular imaging findings were supported by spinal histologic changes in the mutant mice. Thus this state-of-the-art imaging technology has the potential to shorten the time required to diagnose AS and to monitor disease progression and outcome of treatments.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

annulus fibrosus

- Ank:

-

progressive ankylosis

- AS:

-

ankylosing spondylitis

- BM:

-

bone marrow

- DISH:

-

diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- ICG:

-

indocyanine green

- IVD:

-

intervertebral disc

- MMP:

-

matrix metalloproteinase

- mSASSS:

-

modified Stoke AS Spine Score

- NIR:

-

near-infrared

- PPi:

-

inorganic pyrophosphate

- SIJ:

-

sacroiliac joint

- SYN:

-

syndesmophyte

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

Ho AM, Johnson MD, Kingsley DM: Role of the mouse ank gene in control of tissue calcification and arthritis. Science. 2000, 289: 265-270. 10.1126/science.289.5477.265.

Dakwar E, Reddy J, Vale FL, Uribe JS: A review of the pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis. Neurosurg Focus. 2008, 24: E2-

Wang J, Wang C, Tsui HW, Las Heras F, Cheng EY, Iscove NN, Chiu B, Inman RD, Pritzker KP, Tsui FW: Microcytosis in ank/ank mouse and the role of ANKH in promoting erythroid differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2007, 313: 4120-4129. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.008.

Frangioni JV: In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003, 7: 626-634. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007.

Zaheer A, Lenkinski RE, Mahmood A, Jones AG, Cantley LC, Frangioni JV: In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging of osteoblastic activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2001, 19: 1148-1154. 10.1038/nbt1201-1148.

Mahowald ML, Krug H, Taurog J: Progressive ankylosis in mice: an animal model of spondylarthropathy I. Clinical and radiographic findings. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31: 1390-1399. 10.1002/art.1780311108.

Kim HJ, Minashima T, McCarthy EF, Windles JA, Kirsch T: Progressive ankylosis protein (ANK) in osteoblasts and osteoclasts controls bone formation and bone remodeling. J Bone Miner Res. 2010, 25: 1771-1783. 10.1002/jbmr.60.

Kozloff KM, Weissleder R, Mahmood U: Noninvasive optical detection of bone mineral. J Bone Miner Res. 2007, 22: 1208-1216. 10.1359/jbmr.070504.

Zilberman Y, Kallai I, Gafni Y, Pelled G, Kossodo S, Yared W, Gazit D: Fluorescence molecular tomography enables in vivo visualization and quantification of nonunion fracture repair induced by genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2008, 26: 522-530. 10.1002/jor.20518.

Zaheer A, Murshed M, De Grand AM, Morgan TG, Karsenty , Frangioni JV: Optical imaging of hydroxyapatite in the calcified vasculature of transgenic animals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006, 26: 1132-1136. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000210016.89991.2a.

Roelofs AJ, Coxon FP, Ebetino FH, Lundy MW, Henneman ZJ, Nancollas GH, Sun S, Blazewska KM, Bala JL, Kashemirov BA, Khalid AB, McKenna CE, Rogers MJ: Fluorescent risedronate analogues reveal bisphosphonate uptake by bone marrow monocytes and localization around osteocytes in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2010, 25: 606-616. 10.1359/jbmr.091009.

Chang SK, Rizvi I, Solban N, Hasan T: In vivo optical molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor for monitoring cancer treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 4146-4153. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4536.

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A: Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis: a proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27: 361-368. 10.1002/art.1780270401.

Creemers MC, Franssen MJ, van't Hof MA, Gribnan FW, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL: Assessment of outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: an extended radiographic scoring system. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 127-129. 10.1136/ard.2004.020503.

Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H: In vivo molecular imaging of cancer with a quenching near-infrared fluorescent probe using conjugates of monoclonal antibodies and indocyanine green. Cancer Res. 2009, 69: 1268-1272. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3116.

Meier R, Krug C, Golovko D, Boddington S, Piontek G, Rudelius M, Sutton EJ, Baur-Melnyk A, Jones EF, Daldrup-Link HE: Indocyanine green-enhanced imaging of antigen-induced arthritis with an integrated optical imaging/radiography system. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 2322-2327. 10.1002/art.27542.

Erickson SJ, Godavarty A: Hand-held based near-infrared optical imaging devices: a review. Med Eng Phys. 2009, 31: 495-509. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.10.004.

van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Einstein S, Ory P, Vosse D, Ni L, Lin SL, Tsuji W, Davis JC: Radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 1324-1331. 10.1002/art.23471.

van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, Houben H, van Tubergen A, Williamson P, Xu W, Baker D, Goldstein N, Braun J: Radiographic findings following two years of infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 3063-3070. 10.1002/art.23901.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, Edward Dunlop Challenge Research Grant, the Arthritis Society, the Arthritis Center of Excellence, and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FLH participated in the design of the study, carried out molecular imaging, analyzed radiographs and pathology, performed statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. RSD participated in molecular imaging and analysis of the data. KPHP participated in the design of the study, analysis of pathology, and reviewed the manuscript. NH participated in analysis of the radiographs and reviewed the manuscript. GN participated in molecular imaging. HWT and BC participated in animal breeding, genotyping, and data analysis. WME participated in analysis of the radiographs and pathology, interpretation of the data, and critical review of the manuscript. FWLT and RDI participated in the design of the study, coordinated the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Electronic supplementary material

13075_2011_3262_MOESM1_ESM.TIFF

Additional file 1: Radiographs comparing the sacroiliac joints (SIJ) from 8- and 12-week-old wild-typeversus ank/ankmice. No ankylosis was detected. (TIFF 902 KB)

13075_2011_3262_MOESM2_ESM.TIFF

Additional file 2: An old beagle spine with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). (a) A computed tomography (CT) micrograph showing contiguous bony fusion in the lumbar spine, connecting one vertebra to the next. (b) Histopathology of a typical osteophyte, which contains a contiguous bony fusion mass emanating from the vertebral body, complete with bone marrow (BM). A prominent feature in ank/ank spine (ill-defined connective tissue/fibrous tissue mass) is not observed in the old beagle spine. (TIFF 1 MB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Las Heras, F., DaCosta, R.S., Pritzker, K.P. et al. Aberrant axial mineralization precedes spinal ankylosis: a molecular imaging study in ank/ankmice . Arthritis Res Ther 13, R163 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3482

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3482