Abstract

In this study, experimental resin-based primers with varying concentrations of acidic methacrylate were formulated and tested as to their potential in improving the repair bond strength of an aged dental composite resin. The photocurable primers contained (wt%) methacrylate monomers (20-60%), acidic methacrylate (0-40%), silane coupling agent (10%), and ethanol (30%). The pH of the solutions varied between 4.8 and 0.31. The degree of C = C conversion of the primers, measured using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, varied between 22% and 42%, with a linear decrease in conversion associated with increased concentration of acidic methacrylate (R2 = 0.961; p < 0.01). Composite resin blocks aged using 1000 thermalcycles served as substrate for the repair bond strength test. The primers were vigorously applied to the composite surfaces and a silicone mold with cylindrical orifices was placed onto the surface. The orifices were filled with fresh composite resin (simulating the repair). In the control group, no primer was applied. A shear bond test was conducted after 24 h (n = 16 per group). Failure modes were classified under magnification. Data were statistically analyzed at p < 0.05. Repair bond strength values varied between 7.2 and 26.5 MPa. The control group had lower bonding ability than all primed groups. The increased content of acidic methacrylate had no significant association with bond strengths. In the control group only interfacial failures were detected, whereas cohesive failures within the aged composite were observed in the primed groups. In conclusion, application of methacrylate-based primers might improve the repair bond strength of dental composite resins. The concentration of acidic methacrylate on the primer had no significant effect on the immediate repair potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The longevity of dental composite resin restorations depends on a number of factors related to the restored teeth, restorative technique, and restorative materials. Studies indicate that the main reasons for clinical failures of composite restorations are secondary caries and restoration fractures [1, 2]. For many years, when the restorative material failed, the usual treatment indicated was complete replacement of the restoration using fresh composite resin [3]. Complete replacement of the restoration, however, is associated to additional removal of surrounding sound tooth structure [4], enlarging the tooth preparation [5]. Replacing the complete restoration also involves longer clinical chair time, increasing the costs of dental restorative treatments [4, 6, 7].

In the last years, other treatments have been indicated as alternatives to the complete replacement of failed restorations, such as restoration repair or refurbishing. Whereas replacement of existing restorations is defined by complete substitution of the restorative [8], the repair procedure consists in removing only the defective portion of the composite and replacing it with fresh material. It has been reported that repairs might increase the longevity of dental restorations [8, 9]. Another alternative is to refurbish the restoration, i.e., adding new material to the defective portion of the restoration without removing any existing portion of the restorative [10].

Considering that the current concepts of restorative dentistry are conducted by minimally-invasive procedures, repairing a defective restoration may be accounted as a more conservative restorative approach than complete replacement. There are some questions regarding the performance of repaired restorations, particularly concerning the bonding between the aged (old) and fresh composite portions. In vitro studies have reported several surface treatments of the aged composite used to improve the interaction with the new material [4, 5, 11]. However, there are no gold-standard materials or techniques for repairing composite restorations to date. In addition, the treatments reported usually involve the use of acids or sandblasting, which may be considered complicated for intraoral use.

A possibility to improve the interaction between the old and fresh composites in restoration repairs could be the use of methacrylate-based primers to treat the aged surfaces. These repair primers could allow interaction with the old composite by conditioning the surface through a self-etch adhesive approach combined with a chemical coupling provided by co-polymerization. There are no studies reporting on this restorative approach, and no commercial materials are available for that purpose. Therefore, the aim of this study was to formulate experimental resin-based primers to improve the repair bond strength of dental composites. This preliminary investigation focused on the impact that the concentration of acidic methacrylates in the primer would have on the repair outcome. The hypothesis tested was that increasing the acidic methacrylate content would improve the repair bond strength of aged composites.

Methods

Formulation of the experimental repair primers

Methacrylate-based repair primers were formulated by mixing the monomers urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) and 2-hydroxiethyl methacrylate (HEMA), from Esstech Inc. (Essington, PA, USA), with the acidic monomer 1,3-glycerol phosphate dimethacrylate (GDMA-P), and the silane coupling agent 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A 0.4% mass fraction of camphorquinone (CQ, Esstech), relative to the content of resin monomers and silane, was used as photosensitizer and a 0.8% mass fraction of ethyl 4-(dimethylamino)benzoate (EDAB, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as co-initiator. Absolute ethanol (Vetec, Duque de Caxias, RJ, Brazil) was used as a solvent carrier. Five different primers, labeled as P0-40, were obtained by varying the acidic monomer (GDMA-P) concentration (Table 1). The pH of the solutions was measured using a pHmeter (An2000; Analion, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil).

Degree of C = C conversion analysis

The degree of C = C conversion (DC) of each primer (n = 7) was evaluated using Fourier transform mid-infrared spectroscopy (Prestige21; Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) with an attenuated total reflectance device composed of a diamond crystal. A standard volume of the primer was dispensed on the diamond cell. The solvent was evaporated for 20 s using compressed air and a preliminary reading for the unpolymerized material (monomer) was taken using 24 co-added scans and 4 cm-1 resolution. The primer was photoactivated for 20 s using a blue light-emitting diode curing unit (Radii; SDI, Victoria, Australia) with 800 mw/cm2 irradiance. Another spectrum was acquired for the polymerized material. The %DC was calculated as previously described [12].

Preparation of composite specimens

Twenty four blocks (18 × 10 mm, thickness 3 mm) were prepared by incrementally placing a commercially available microhybrid composite resin (Opallis; FGM, Joinville, SC, Brazil), shade A2, into a silicone mold. Photoactivation of each increment was carried out for 20 s. The blocks were aged using 1000 thermalcycles in distilled water at 5 ± 5°C and 55 ± 5°C, with a 60 s dwell time [13–15]. The aged specimens were embedded in epoxy resin and grounded with 600- and 1200-grit SiC abrasive papers to simulate the surface preparation used in the clinical setup before a composite repair is carried out.

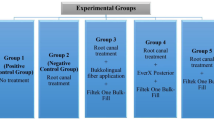

Repair bond strength test

The experimental primers were vigorously applied to the surface of the composite blocks for 20 s using a microbrush and were gently dried for 10 s using compressed air. To delimitate the bonded area, a silicone mold (thickness 0.5 mm) with four cylindrical orifices (diameter 1.5 mm) was placed onto the surface of the blocks and the primer was photoactivated for 20 s. The orifices were filled with fresh composite resin (Opallis) to simulate the repair procedure and covered with a polyester strip and a glass slide. The composite was photoactivated for 20 s. In the control group, no primer was applied to the composite blocks (unprimed specimens). The distance between the repair composite cylinders was ≥4 mm. The repaired specimens were stored in distilled water at 37°C. After 24 h, a thin wire was looped around each composite cylinder and a shear bond strength test was conducted on a mechanical testing machine (DL500; EMIC, São José dos Pinhais, PR, Brazil) at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until failure. Repair bond strength values were recorded in MPa. For each composite block 4 repair resin cylinders were obtained, defining a total of 16 cylinders (4 composite blocks) tested for each group. The composite cylinders were considered the experimental units.

Failure analysis

After the shear bond strength test, the surface of the aged composite was examined with a stereomicroscope under a 40× magnification. The failure modes were classified as adhesive (interfacial failure) or cohesive within the aged composite.

Statistical analysis

DC and bond strength data were analyzed using ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls as post hoc test. The relationship between acidic monomer concentration and DC or bond strength was investigated using linear regression analysis. A significance level of α = 0.05 was set for all analyses.

Results and discussion

Results for DC and repair bond strength are shown in Table 2. The power of the performed test was = 1 for both statistical analyses. Whereas no significant differences in DC were observed between P0 and P10 (p = 0.444), all other comparisons indicated significant differences between the primers (p ≤ 0.0042). A significant linear decrease in DC was associated with increased concentration of GDMA-P. This finding is explained by the lower pH of the solutions (Table 1) reducing the methacrylate polymerization rate and extent [16, 17]. These events occur due to the ability of the acidic monomers in quenching free radicals [18] and due to the fact that monomers terminated by an acid group are less reactive as compared with regular methacrylates [19]. In addition, the incorporation of GDMA-P was conducted by replacing UDMA and HEMA, which are more reactive in the polymerizing reaction environment than GDMA-P [20]. In contrast to DC, the increased content of GDMA-P had no significant association with bond strength.

The control group had significantly lower bond strength than all primed groups, irrespective of the acidic methacrylate concentration (p < 0.001). This finding indicates that all primers were effective in improving the immediate repair potential of the aged composite, although the acidic methacrylate concentration had no significant effect on the bonding ability (p ≥ 0.118). Thus, the hypothesis tested was rejected. The rationale of increasing the concentration of acidic methacrylate was related to a possible increased surface etching aggressiveness [21], which could lead to improved mechanical keying with the composite surface. Additionally, the higher content of acidic methacrylates could lead to better chemical interaction with the glass filler particles of the aged composite. A mechanism for the bond between acid-derivative methacrylates and glass particles based on an ionic interaction between the acid and silanol groups has been recently proposed [22]. The minor effect of the GDMA-P concentration on the bonding ability is probably related to the low reactivity of the aged polymer network and low surface area of glass particles available on the composite surface for chemical coupling. Notwithstanding, the role of the acidic methacrylate on the longevity of the repair bonds will be addressed in a future investigation.

Results for the failure analysis (Figure 1) indicated that only interfacial failures were detected in the control group, whereas cohesive failures within the aged composite were observed in the primed groups. Aging of the dental composite was simulated by thermalcycling, which might reduce the mechanical strength of polymers [13, 23]. This could explain the occurrence of cohesive failures within the aged composite during the shear test, which is known to lead to stress concentration underneath the bonded interfaces [24]. However, a predominance of interfacial failures was generally observed for all treated groups, except for P0 and P30. Interfacial failures are characterized by complete debonding between the fresh and aged composite interfaces. The high occurrence of interfacial failures is probably related to the inability of the primer in creating surface irregularities for a strong mechanical interlocking, or inability in providing proper chemical interaction with the aged composite.

The lower DC observed for primers with higher GDMA-P concentration was not associated with lower bonding potential. This result corroborates the findings of a previous investigation showing that the DC only marginally affected the early bond strengths of resin-based primers to a polycrystalline zirconia ceramic [17]. The impact of higher DC on the stability of the repair bonds is yet to be determined, since higher conversion and improved mechanical strength of the bonded assembly could reduce the hydrolytic effects that water may have on the primed repair surfaces.

The literature reports several methods used in an endeavor to improve the bond strength between fresh and aged composites in restoration repairs. These methods include application of chemicals (chemical treatment), use of abrasion with diamond points or sandblasting with alumina particles (mechanical treatment), or a combination of chemical and mechanical treatments [4, 5, 11]. The present investigation reported on the use of methacrylate-based repair primers, showing that priming the aged composite was effective in improving the repair bond strength as compared with the untreated group. Application of surface primers can be accounted as a simple, cost-effective, and safe method for use in the intraoral environment. However, the formulation of the primers needs to be further addressed. In this study, one basic solution was elected to be highlighted for the purpose of improving the repair bond strength of aged composites. The effects of variations in the selection and relative concentrations of different components on the immediate and long-term repair bond strengths will be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

Application of methacrylate-based primers might improve the repair bond strength of dental composite resins. The concentration of acidic methacrylate on the primer had no significant effect on the immediate repair potential.

References

Hickel R, Manhart J: Longevity of restorations in posterior teeth and reasons for failure. J Adhes Dent 2001, 3: 45–64.

Mjor IA, Moorhead JE, Dahl JE: Reasons for replacement of restorations in permanent teeth in general dental practice. Int J Dent 2000, 50: 361–366. 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00569.x

Gordan VV, Shen C, Riley J 3rd, Mjor IA: Two-year clinical evaluation of repair versus replacement of composite restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent 2006, 18: 144–153. 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2006.00007.x

Baur V, Ilie N: Repair of dental resin-based composites. Clin Oral Investig 2012, 17: 601–608.

Papacchini F, Toledano M, Monticelli F, Osorio R, Radovic I, Polimeni A, et al.: Hydrolytic stability of composite repair bond. Eur J Oral Sci 2007, 115: 417–424. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00475.x

Mjor IA, Gordan VV: Failure, repair, refurbishing and longevity of restorations. Oper Dent 2002, 27: 528–534.

Moncada G, Fernandez E, Martin J, Arancibia C, Mjor IA, Gordan VV: Increasing the longevity of restorations by minimal intervention: a two-year clinical trial. Oper Dent 2008, 33: 258–264. 10.2341/07-113

Hickel R, Brushaver K, Ilie N: Repair of restorations–criteria for decision making and clinical recommendations. Dent Mater 2013, 29: 28–50. 10.1016/j.dental.2012.07.006

Demarco FF, Correa MB, Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJ: Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dent Mater 2012, 28: 87–101. 10.1016/j.dental.2011.09.003

Fernandez EM, Martin JA, Angel PA, Mjor IA, Gordan VV, Moncada GA: Survival rate of sealed, refurbished and repaired defective restorations: 4-year follow-up. Braz Dent J 2011, 22: 134–139.

Ozcan M, Alander P, Vallittu PK, Huysmans MC, Kalk W: Effect of three surface conditioning methods to improve bond strength of particulate filler resin composites. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2005, 16: 21–27.

Moraes RR, Faria-e-Silva AL, Ogliari FA, Correr-Sobrinho L, Demarco FF, Piva E: Impact of immediate and delayed light activation on self-polymerization of dual-cured dental resin luting agents. Acta Biomater 2009, 5: 2095–2100. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.030

Ozcan M, Cura C, Brendeke J: Effect of aging conditions on the repair bond strength of a microhybrid and a nanohybrid resin composite. J Adhes Dent 2010, 12: 451–459.

Rinastiti M, Ozcan M, Siswomihardjo W, Busscher HJ: Effects of surface conditioning on repair bond strengths of non-aged and aged microhybrid, nanohybrid, and nanofilled composite resins. Clin Oral Investig 2011, 15: 625–633. 10.1007/s00784-010-0426-6

Hannig C, Hahn P, Thiele PP, Attin T: Influence of different repair procedures on bond strength of adhesive filling materials to etched enamel in vitro. Oper Dent 2003, 28: 800–807.

Moraes RR, Boscato N, Jardim PS, Schneider LF: Dual and self-curing potential of self-adhesive resin cements as thin films. Oper Dent 2011, 36: 635–642. 10.2341/10-367-L

Moraes RR, Guimaraes GZ, Oliveira AS, Faot F, Cava SS: Impact of acidic monomer type and concentration on the adhesive performance of dental zirconia primers. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes 2012, 39: 49–53.

Sanares AM, Itthagarun A, King NM, Tay FR, Pashley DH: Adverse surface interactions between one-bottle light-cured adhesives and chemical-cured composites. Dent Mater 2001, 17: 542–556. 10.1016/S0109-5641(01)00016-1

Adusei G, Deb S, Nicholson JW, Mou LY, Singh G: Polymerization behavior of an organophosphorus monomer for use in dental restorative materials. J Appl Polym Sci 2003, 88: 565–569. 10.1002/app.11437

Sideridou I, Tserki V, Papanastasiou G: Effect of chemical structure on degree of conversion in light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials 2002, 23: 1819–1829. 10.1016/S0142-9612(01)00308-8

Lima GS, Ogliari FA, Moraes RR, Mattos ES, Silva AF, Carreño NL, et al.: Water content in self-etching primers affects their aggressiveness and strength of bonding to ground enamel. J Adhes 2010, 86: 937–950.

Habekost LV, Camacho GB, Lima GS, Ogliari FA, Piva E, Moraes RR: Properties of particulate resin-luting agents with phosphate and carboxylic functional methacrylates as coupling agents. J Appl Polym Sci 2013, 127: 3467–3473. 10.1002/app.37627

Feitosa VP, Fugolin AP, Correr AB, Correr-Sobrinho L, Consani S, Watson TF, et al.: Effects of different photo-polymerization protocols on resin-dentine μTBS, mechanical properties and cross-link density of a nano-filled resin composite. J Dentist 2012, 40: 802–809. 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.05.014

Versluis A, Tantbirojn D, Douglas WH: Why do shear bond tests pull out dentin? J Dent Res 1997, 76: 1298–1307. 10.1177/00220345970760061001

Acknowledgements

The authors thank FGM Produtos Odontológicos for donation of the composite resin and Esstech Inc. for donation of reagents.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LLV and EAM participated in the study design, data collection, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and critical revision. MFS and ISM participated in the laboratory analyses, data collection and critical revision. RRM participated in the study design, supervision of laboratory research, data interpretation, manuscript drafting and critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Valente, L.L., Münchow, E.A., Silva, M.F. et al. Experimental methacrylate-based primers to improve the repair bond strength of dental composites – a preliminary study. Appl Adhes Sci 2, 6 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-4351-2-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-4351-2-6